The FIFA World Cup, the once-every-four-years most-watched and most lucrative event in sports, is now less than three months away.

Qatar, this year's host, is one of the world's richest countries per capita. But this is a case of the haves and the haves not.

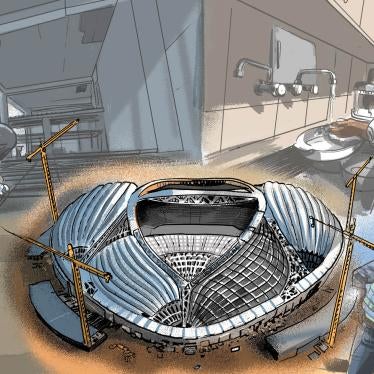

Millions of migrant laborers built an estimated $220 billion in new construction for the event since the tournament was awarded to Qatar 12 years ago, including eight stadiums, and as FIFA required, an expansion of the airport and new hotels, plus rail and highways to football venues. The human cost has been even higher: Several thousand people who migrated to Qatar from some of the poorest countries to work as laborers preparing for the World Cup have died from the heat and poor working and living conditions.

This should come as no surprise to the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA), which owns the World Cup brand. When FIFA granted the World Cup to Qatar in 2010, football leaders knew or should have known about Qatar's exploitative labor system and lack of worker protections. Temperatures there can reach more than 120 degrees Fahrenheit, almost 50 degrees Celsius.

"Of course it was a mistake," Sepp Blatter, FIFA's former president, said in 2014, citing a FIFA report he said had "clearly indicated that it was too hot in the summer."

FIFA granted Qatar the games, even though it had and has serious human rights problems. FIFA did no human rights due diligence and set no conditions about protections for migrant workers. Nor were protections required for journalists, women, LGBTQ+ people, athletes or fans, despite the shameful history of sportswashing and horrific abuses when global sporting events were handled by other authoritarian governments such as China and Russia.

FIFA ultimately moved the World Cup to November 2022 to protect the athletes. But there was no such concern for the more than 2 million migrants working in Qatar at any one time building stadiums, roads, and hotels.

It's impossible to know exactly how many workers died. Official Qatari statistics show that 15,021 non-Qataris died in the country between 2010 and 2019. The Guardian contacted embassies in Qatar for five countries—India, Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka—and was able to confirm at least 6,750 migrant workers who died in Qatar since the games were awarded in 2010. This is likely an undercount of worker deaths on World Cup infrastructure, because there are a dozen more countries sending migrant workers to Qatar, including the Philippines, Kenya, and Ghana.

Kripal Mandal left his home in Nepal to earn a better life for his family. He died in Qatar in February, just one more tragedy among the thousands of migrant workers who have died of what officials said were "natural causes" while preparing essential tournament infrastructure. Under the U.N. Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, Mandal's impoverished family should be able to claim compensation from FIFA and Qatar. But when deaths are attributed to "natural causes" and categorized as non-work-related, Qatar's labor law denies families any compensation. Mandal's employer didn't even pay the 15 days of salary he was contractually owed.

At a May 2 conference, "Managing the Beautiful Game," FIFA President Gianni Infantino was asked whether FIFA supports the families of the workers who died building these stadiums. He replied, "When you give work to somebody, even in hard conditions, you give him dignity and pride." He later added, "Now 6,000 might have died in other works and so on ... [but] FIFA is not the police of the world."

Qatar's abusive "Kafala" labor sponsorship system grants disproportionate power and control to employers. Workers are barred from joining unions or from striking even over dangerous working conditions. As recently as March, Human Rights Watch documented wage theft by a prominent Qatari construction firm with FIFA-related projects. It is still the norm for most migrant workers in Qatar to pay exorbitant recruitment fees that can be a form of debt bondage.

Since the World Cup was awarded, Qatar's labor practices have been in the spotlight, including a forced labor complaint before the International Labour Organization (ILO). Qatar eventually put in place some reforms, including a minimum wage, allowing job mobility, and mostly removing the abusive exit permit requirement for migrant workers.

But these reforms didn't address the many worker deaths. Migrant workers continue to return home from Qatar in coffins.

FIFA may deny responsibility, but it has clear commitments under its own statutes and the responsibilities it accepted to ensure host countries comply with basic human rights rules.

The families of migrant workers who died or were injured in Qatar say they are losing hope. They have no lawyers, no support, little or no ongoing contact with the sponsoring companies, and limited means of contacting FIFA or Qatar to appeal for compensation. Economic hardship may drive some of the workers' children into child labor or child marriage simply because their families didn't have funds to feed them or send them to school.

FIFA and Qatar cannot bring migrant workers' families back their loved ones, but the least they can do is set up a compensation fund to support the families of workers who died to make the 2022 World Cup possible.