This questions and answers document addresses key questions regarding the failure by Qatar and FIFA, football’s world governing body, to protect migrant workers in the lead-up to FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022.

- Why have migrant workers faced serious abuses in Qatar and other Gulf countries for decades?

- Qatari authorities have made major labor reform commitments and claim they have implemented them. Have they?

- But didn’t Qatar “dismantle” the abusive kafala (sponsorship) system?

- Are migrant workers able to change jobs easily in Qatar now?

- What about workers’ ability to leave the country, including without an employer’s permission?

- Don't workers still go to Qatar because they expect to earn better wages than in their home countries?

- Qatari authorities reject reports around migrant worker deaths, what does the actual evidence indicate?

- What should the authorities do to address this dismal reality of unexplained migrant worker deaths in Qatar?

- Are migrant workers free to speak out on the abuses they face?

- Is Human Rights Watch joining the call for boycotting FIFA 2022?

- What are FIFA’s responsibilities for the human rights situation in Qatar, and has the world football governing body lived up to them since awarding the World Cup to Qatar in 2010?

- Who is sponsoring FIFA and the 2022 World Cup? Have these companies spoken up on migrant abuses?

- What can fans, players, and other stakeholders do over the next year to make a difference?

- Despite worker abuses, Qatar seems to be attracting some influential people to act as brand ambassadors. What should these brand ambassadors do to address human rights abuses?

- What happens to migrant workers in Qatar after the 2022 World Cup ends?

- Do other Gulf countries have similar sponsorship systems? If so, has Human Rights Watch documented worker abuses in other Gulf countries?

The kafala (sponsorship) system, a restrictive labor governance system used across the Arab Gulf region as well as Jordan and Lebanon, is at the heart of most of the abuses and exploitation migrant workers face. This abusive system, which varies in implementation from one country to the other, in some cases may amount to modern slavery, grants employers disproportionate power and control over migrant workers’ immigration and employment status, and thereby their lives. Five elements of the kafala system can keep migrant workers trapped in abusive conditions:

- A migrant worker’s need to have an employer act as their sponsor to enter the country.

- The power employers have to secure and renew migrant workers’ residency and work permits, and their ability to cancel these at any time.

- The requirement for migrant workers to obtain their employers’ consent to leave or change jobs.

- The crime of “absconding,” under which employers can report a migrant worker missing, meaning the worker automatically becomes undocumented and can be arrested, imprisoned, and deported.

- The requirement for migrant workers to have an exit permit to leave the country, which is often compounded by requiring them to obtain their employer’s consent.

Human Rights Watch has documented how these elements of the kafala system facilitate abuse and exploitation. Workers have little power to complain about or escape abuse when their employer controls their entry and exit from the country, residency, and ability to change jobs. Many employers exploit this control by confiscating workers’ passports, forcing them to work excessive hours and denying them wages. Migrant domestic workers in particular can be confined to their employers’ homes and may be subject to physical and sexual abuse. The kafala system has also led to many migrant workers losing their legal status, making them subject to arrest, detention and forcible deportation and leaving them acutely more vulnerable to abuses.

Unfortunately, they have not.

In 2017, under pressure from the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) and investigation by the International Labour Organization (ILO) “concerning non-observance by Qatar of the Forced Labour Convention,” Qatar pledged a series of important reforms in the following areas:

- Improve wage protection;

- Improve labor inspection and occupational safety and health;

- Replace the kafala system with an employment contract system;

- Prevent forced labor; and

- Promote workers’ voices.

These commitments came seven years after Qatar won the bid to host the World Cup in 2010, but still offered hope in terms of curbing the most serious abuses and safeguarding migrant rights. Since then, Qatar has embarked on several reform initiatives to better protect the lives and rights of migrant workers including:

- Strengthening the Wage Protection System (WPS), meant to ensure migrant workers are paid in a timely and accurate fashion;

- Introducing the Worker’s Support and Insurance Fund, partly designed to make sure workers are paid unclaimed wages when companies fail to pay;

- Introducing a nondiscriminatory minimum wage;

- Lifting restrictions on migrant workers’ ability to change employers and exit the country without their employers’ written consent;

- Establishing the Labour Dispute Resolution Committees, designed to speed up the litigation process and shorten the time it takes to resolve labor disputes.

However, research by Human Rights Watch and other migrant and human rights organizations demonstrates that the labor reforms are woefully inadequate and poorly enforced, with migrant workers’ continuing to suffer serious labor abuses, from passport confiscation to unpaid and delayed wages and even forced labor. With one year left before the World Cup, a bolder approach is required to ensure that Qatar follows through on its promises, both on paper and in practice.

- But didn’t Qatar dismantle” the abusive kafala (sponsorship) system?

No. The reforms Qatar introduced did not dismantle the kafala system in its entirety. Employers still wield tremendous control over migrant workers’ lives, allowing them to evade accountability for labor and human rights abuses, and leaving workers debt-burdened and in constant fear of retaliation.

Key elements of the kafala system remain completely unaddressed, including the criminalization of “absconding.” Penalties for absconding can include fines, detention, deportation, and a ban on re-entry. This means employers can falsely report workers as having “absconded,” invalidating the worker’s legal status even if they are simply escaping an employer’s abuse.

No. Qatari authorities loudly trumpeted ending the government requirement for migrant workers to acquire a no-objection certificate, or NOC, from their current employers before they are able to change jobs. However, in reality the success of even this minor reform is largely illusory. Data Qatari authorities have released on the number of migrant workers who have managed to change jobs conceals more than it reveals, as the authorities have withheld sharing the total number of applications for job changes and the number of applications rejected.

And while the NOC requirement may have been scrapped, migrant workers are still required by the government to obtain signed letters approving their resignation from their original employer – essentially creating a de-facto NOC – before they are allowed to switch jobs, which gives employers disproportionate control over workers. Similarly, a large proportion of hiring employers also make NOCs mandatory in their job vacancy announcements. Many employers are also demanding that workers pay high costs for the NOCs, leaving the migrants at high risk of indebtedness and in some cases may even amount to forced labor.

Qatar announced on January 16, 2020, that it had lifted the abusive exit permit requirement for most migrant workers, and this reform has made it easier for many migrant workers to leave the country without the employer’s permission. Domestic workers, however, still need to inform their employers 72 hours in advance about their departure and employers are still allowed to request that 5 percent of their workforce require exit permits.

Other challenges also remain for migrant workers who want to leave Qatar. Employers confiscating migrant workers’ passports is still a widespread practice, even though it is illegal. Employers also often refuse to provide the migrant worker with return airfare, leaving them unable to afford a flight home. Employers have also falsely reported that workers who insisted on leaving had “absconded,” leaving them at risk of fines, detention, and forcible deportation.

Qatar still does not guarantee, everyone’s right regardless of status, to leave the country. This would mean scrapping the exit permit system in its entirety.

Yes, often migrant workers take jobs in Qatar expecting to make more money, but in reality, they are often cheated out of their promised wages in a variety of ways. These include unpaid overtime, arbitrary deductions, delayed wages, withholding of wages, unpaid wages, or inaccurate wages as Human Rights Watch has extensively documented. Workers still pay exorbitant recruitment fees to secure the jobs in Qatar, between 700 USD and 2,600 USD, which makes them vulnerable even as they arrive in Qatar due to high indebtedness.

This is despite several notable reforms that Qatar has introduced since 2015 to ostensibly enhance wage protection for migrant workers. The Wage Protection System, essentially a notification system, still has shortcomings that allow employers to outsmart the system and steal wages. It still is not entirely clear how or when the authorities utilize the Worker’s Support and Insurance Fund to benefit struggling workers. Labour Dispute Resolution Committees remain slow, inaccessible, and ineffective. Abusive employers are not held to account while penalties for violations are insufficient.

Reforms aimed at wage protection mean little for migrant workers if employers can withhold, delay, and deduct from their wages without consequences. Such abuses also remain a high risk during the World Cup 2022, beginning on November 21, 2022, when an estimated 1.2 million fans will be visiting Qatar.

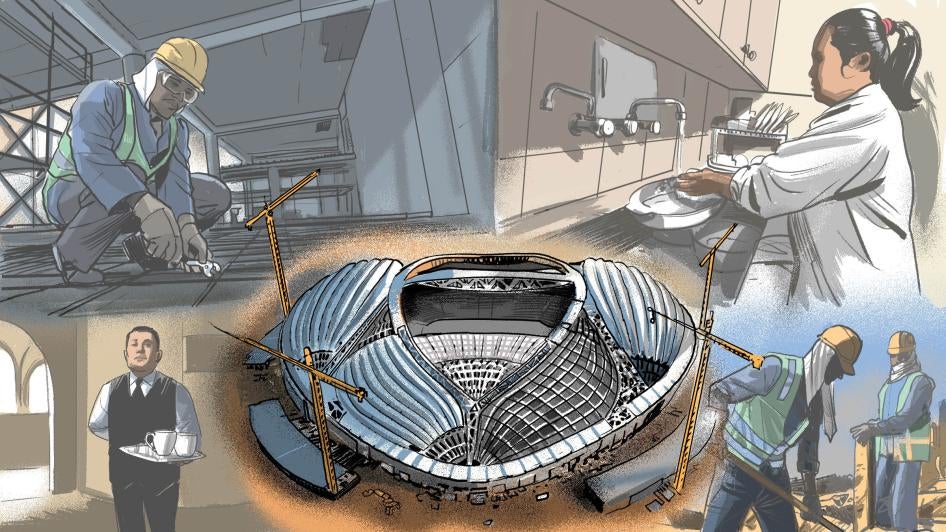

Airport workers, drivers, hotel workers, restaurant staff, and stadium workers whom fans and players encounter in Qatar are all going to be migrant workers. Every migrant worker involved in the delivery of the World Cup that a fan or a player comes across in Qatar could potentially be a victim of some form of wage abuse.

- Qatari authorities reject reports around migrant worker deaths, what does the actual evidence indicate?

There is no justification for the unexplained deaths of thousands of young, healthy adults.

Qatar has failed to publicize sufficient data on worker deaths despite consistent pressure by organizations like Human Rights Watch. The Qatari authorities say that the number of non-Qatari deaths between 2010 and 2019 is 15,021 for all ages, occupations, and causes. But because the data is neither disaggregated nor comprehensive, it is difficult to do any meaningful analysis of migrant worker deaths. A Guardian investigation shows that between 2010 to 2020, there were over 6,751 deaths in Qatar of people from just five South Asian countries which were neither categorized by occupation nor place of work. According to a recently commissioned report by the International Labour Organization (ILO), there were 50 work-related deaths in Qatar in 2020, and these have been disaggregated by key characteristics such as places of injury and death and the underlying cause where available.

Furthermore, the rate of unexplained deaths is demonstrable, and a high share of these deaths could potentially have been prevented. According to the Guardian investigation, 69 percent of the deaths of migrant workers from India, Nepal and Bangladesh between 2010 and 2020 were attributed to “natural causes.” A fifth of the 50 work-related deaths from 2020 were attributed to “unknown causes,” the ILO reported.

According to the Supreme Committee’s Workers’ Welfare Progress Reports, 18 of the 33 fatalities recorded between October 2015 and October 2019 attribute the cause of death to “natural causes,” “cardiac arrest,” or “acute respiratory failure,” terms that obscure the underlying cause of deaths and make it impossible to determine whether they may be related to working conditions, such as heat stress. When deaths are attributed to “natural causes” and categorized as non-work-related, Qatar’s labor law denies families compensation, leaving many of them destitute in the absence of their often-sole income provider.

For a country with a highly advanced healthcare system, it is unfathomable that transparent data on worker deaths isn’t available and meaningful investigations of deaths have not been conducted but are simply attributed to “unknown” or “natural causes.” This does not prevent future deaths nor provide any consolation to the grieving families who are left in the dark.

Qatari authorities have shown an appalling apathy to this terrible stain on its and FIFA’s record in the lead-up to the World Cup. Qatar needs to:

- Immediately commission an independent, thorough, and transparent investigation by a team of qualified public health professionals into the causes of past migrant workers’ unexplained deaths;

- Identify and compensate the families of migrant workers who have died in unexplained circumstances.

Qatar should also significantly invest in better quality and more accurate data collection of work-related deaths and injuries that would form the basis for meaningful analysis and evidence-based policymaking. Research published in the Cardiology Journal in 2019 by a group of climatologists and cardiologists explored the relationship between the deaths of more than 1,300 Nepali workers between 2009 and 2017 and heat exposure. They found a strong correlation between heat stress and young workers dying of cardiovascular problems in the summer months.

In addition, it is equally important to prioritize health concerns that migrant workers in Qatar are facing and will continue to face that stop short of death but are equally worthy of attention. Health concerns regarding migrant returnees from Qatar include but are not limited to kidney/renal issues, persistent heat strokes, long-term effects of heat stress, mental health issues, work-related injuries/accidents, malnutrition, blood pressure, erratic sugar levels, and diabetes that they may have developed or experienced during or after their time in Qatar.

In 2021, Qatar introduced new measures meant to increase protections from heat stress. However, the new legislation offers only marginally more protection for workers, and considerably less than required. Key features of the legislation include an extension of the demonstrably ineffective blanket prohibition on outdoor work during the hottest months of the year and the prohibition of work when the wet-bulb globe temperature exceeds 32.1 degrees.

Qatar needs to take concrete actions to improve the overall health of migrant workers and their access to proper health care, nutrition, accommodation, and social protection.

Definitely not. Freedom of expression in Qatar is extremely restricted for citizens, and even more so for non-citizen residents, who are at risk of immediate and arbitrary deportation. Over the last year alone, Qatari authorities forcibly disappeared the Kenyan labor activist Malcolm Bidali before releasing him and put Abdullah Ibhais, a Jordanian former employee of the Supreme Committee, on trial for bribery and misuse of funds, which some evidence suggests was in retaliation for his criticism of the poor conditions for migrant workers.

Qatar bans migrant workers from protesting, strikes, or joining trade unions. While Qatar joined the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in 2018, it maintained several formal reservations, including interpreting the term “trade unions” in accordance with its national law. Article 116 of Qatar’s Labor Law allows only Qatari nationals the right to form workers’ associations or trade unions, depriving migrant workers of their rights to freedom of association and to form trade unions.

In lieu of this right, Qatar committed to allowing joint committees that include representatives of both the company and its workforce as part of its agreement with the International Labour Organization (ILO). The first joint committee was formed in 2019 and by 2020, 107 representatives of 17,000 employees in 20 companies had been elected. However, as Amnesty International has documented, joint committees are flawed as they are led by employers and fall short of providing the same crucial protections as those offered by independent worker-led trade unions.

Human Rights Watch has repeatedly said that Qatar should amend the labor law to guarantee migrant workers’ right to strike and form trade unions and to free association and collective bargaining.

Human Rights Watch does not take a position on boycotts of sporting, cultural, or educational events or exchanges. Individuals have the right under international human rights law to express their views through non-violent means, including participating in boycotts. Human Rights Watch considers the actions of teams and football associations to draw attention to the human rights abuses to be positive steps, such the Danish Football Association’s recent decision not to participate in commercial activities arranged by World Cup organizers to highlight human rights issues. For players and individuals who are able to speak out on human rights issues, Human Right Watch suggests they call on FIFA and Qatar to meet their human rights obligations and responsibilities.

FIFA has been a dismal steward of protecting and promoting human rights in Qatar. To start with, FIFA decided to award Qatar the 2022 hosting rights without human rights due diligence or imposing labor rights conditions, all while knowing there was a massive infrastructure deficit that would rest on vulnerable migrant workers to build.

FIFA adopted the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights in 2016, and promulgated a Human Rights Policy in 2017, but it has not demanded that the Qatar government should uphold human rights, including amending repressive laws on press freedom, LGBT rights, women’s rights, and ending labor abuses.

Despite repeated warnings for years of serious human rights abuses against migrant workers in Qatar, and having the authority to take action, FIFA has ignored these abuses, including an appalling number of unexplained deaths, serious physical injuries, and widespread wage theft. FIFA should address these abuses since they have failed to pressure Qatar to uphold the country’s human rights obligations. FIFA is benefitting from the sweat of the workers who have literally built the World Cup and has the resources to compensate the loss of migrant workers’ lives and livelihoods, but it has failed to live up to their own human rights responsibilities.

The international scrutiny and pressure from organizations like Human Rights Watch over the years has made human rights central to FIFA’s operations. In 2016, FIFA adopted the UN Guiding Principles for Business and Human Rights and enshrined its responsibility to respect human rights in Article 3 of the FIFA Statutes. It also set up an independent Human Rights Advisory Board, employed human rights staff, set up a complaints mechanism for human rights defenders and in 2017, adopted a human rights policy stating that human rights commitments are binding on all FIFA bodies and officials. In addition, FIFA has introduced new requirements on human rights for bidding and hosting future World Cups. Bidding countries are now required to submit a human rights strategy in preparing for and hosting the tournament. This is especially crucial noting that countries like Saudi Arabia with poor human rights records are also vying to secure hosting rights.

While these are positive developments, FIFA needs to make reparations to the thousands of migrant workers or their families who sustained abuse to make the World Cup 2022 possible.

FIFA’s decision to award hosting rights to Qatar has been mired with controversies, starting with US Department of Justice allegations that FIFA officials were bribed to award Qatar the 2022 World Cup.

FIFA partners include Visa, Hyundai-Kia, Coca-Cola, Adidas, Wanda Group, and Qatar Airways. FIFA 2022 World Cup sponsors include Budweiser, Anheuser-Busch InBev SA/NV, McDonald’s, Vivo, Hisense, and Mengniu.

Given the billions of dollars sponsors collectively spend on the games, and their own adoption of the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, they have leverage to pressure FIFA to urge Qatar to deliver reforms for migrant workers as committed and to prevent their image from being tarnished by association with rights abuses. As the tournament draws close, sponsors should:

- Speak up consistently and boldly on migrant rights abuse in Qatar and the lack of implementation of reforms;

- Pressure FIFA to step up and take responsibility for migrant abuses, especially to investigate unexplained migrant deaths and provide compensation to their families;

- Pressure FIFA and Qatari authorities to ensure that service workers involved in the delivery of the World Cup are recruited ethically and employed as per the terms of contract. Recent evidence has shown that hotel workers in Qatar, for example, paid high recruitment costs to secure these jobs.

Fans and players likely don’t want to sit in stadiums migrant workers died building, or to stay in hotels where migrant workers face wage cheating and other rampant abuses. It is because of global pressure by fans and athletes that FIFA adopted a human rights policy and why Qatar has constantly come under scrutiny despite its attempts to launder its image via massive public relations campaigns.

As the clock ticks closer to the World Cup 2022, football players, football associations, and fans have increasingly become vocal against the violations of migrant workers’ rights in Qatar. The collective power of influential football players and the estimated 3 billion fans who will be enjoying the game from all over the world in stadiums built by migrant workers can be immense. However, real change requires sustained pressure demanding actionable reforms – on FIFA, sponsors and Qatari authorities – now more than ever.

Fans, Football Associations, and players could:

- Pressure FIFA to initiate an investigation of migrant abuses including unexplained deaths and ensure that migrant workers or their families are adequately compensated;

- Pressure FIFA to urge Qatari authorities to dismantle the abusive kafala system in its entirety as it has repeatedly promised.

Brand ambassadors who are willing to be the face of the World Cup have a unique platform and the responsibility to speak up on human rights abuses. They first need to educate themselves on the on-the-ground realities and go beyond what the Qatari public relations machine feeds them. They need to understand the authorities’ intention to use such events to “sportswash” their abysmal human rights record and deflect scrutiny. They need to understand that the reform narrative Qatari authorities have built around worker welfare does not reflect migrant realities and that abuses are still pervasive. Agreeing to be the face of such events while staying mute on the rampant abuse signals complacency. There is no celebration if it comes at the cost of migrant lives, rights, and basic dignity.

To isolate the game from the millions of workers who are making the tournament possible amid rampant abuse is wrong.

Migrant workers comprise approximately 95 percent of the workforce in Qatar. Without them, daily life in the country would come to a halt. Mega-events like FIFA with a global appeal can serve as an important opportunity to put the spotlight on human rights abuses and to create pressure for durable reforms. The reforms introduced over the last decade is a testament to the global scrutiny, but more needs to be done ahead of the World Cup to ensure that the reforms are not half measures but truly benefit migrant workers without whom such events would not be possible.

The next year will determine the legacy that FIFA leaves behind in Qatar in terms of its influence in steering lasting reforms. Beyond 2022 too, however, it will be especially important to continue monitoring, documenting and exposing abuses and rights violations in Qatar and to ensure that migrant workers do not fall through the cracks sans the global spotlight.

The Arab Gulf as well as Jordan and Lebanon impose various forms of the kafala (sponsorship) system. While Qatar’s reform process has dominated international news, other governments too have declared their intention to restructure or reform their kafala (sponsorship) systems.

At present, the entry of migrant workers to all eight countries is tied to their employers. All countries allow migrant workers to leave the country without employer approval except for Saudi Arabia, which requires domestic workers to have an exit permit from their employer. Only Bahrain and the UAE allow some workers to be responsible for renewing their own residence permits, but the UAE still requires employers to renew residence permits for domestic workers. Qatar, the UAE, Bahrain, and Saudi Arabia allow some migrant workers to terminate or transfer employment whether during or at the end of the contract. In all countries, workers who leave their employer without consent can be charged with “absconding” and face penalties such as imprisonment, fines for overstaying, and deportation.

Human Rights Watch has consistently documented migrant rights violations in the Gulf countries and exposed the central role of the kafala system in enabling such abuses by giving disproportionate power to employers over migrant workers. As Gulf countries increasingly commit to restructuring or reforming their kafala systems, Human Rights Watch has sought to critically examine the adequacy of announced reforms in addressing core migrant vulnerabilities and closely monitor their subsequent implementation.