Summary

When “Henry,” a Kenyan man, received the complete list of required documents that allowed him to work in Qatar, he thought all his prayers had been answered.[1] To secure a plumbing job in Qatar, he had to take a loan at a 30 percent interest rate in order to pay a Kenyan recruitment agent a fee of 125,000 Kenyan shillings (US$1,173). But Henry, 26, was happy because his employment contract promised him 1,200 Qatari riyals ($329) a month, which would allow him to pay back his loan, plus an additional food allowance, employer-paid accommodation, and overtime payments for each hour of work he performed above the 8-hours-a-day limit.

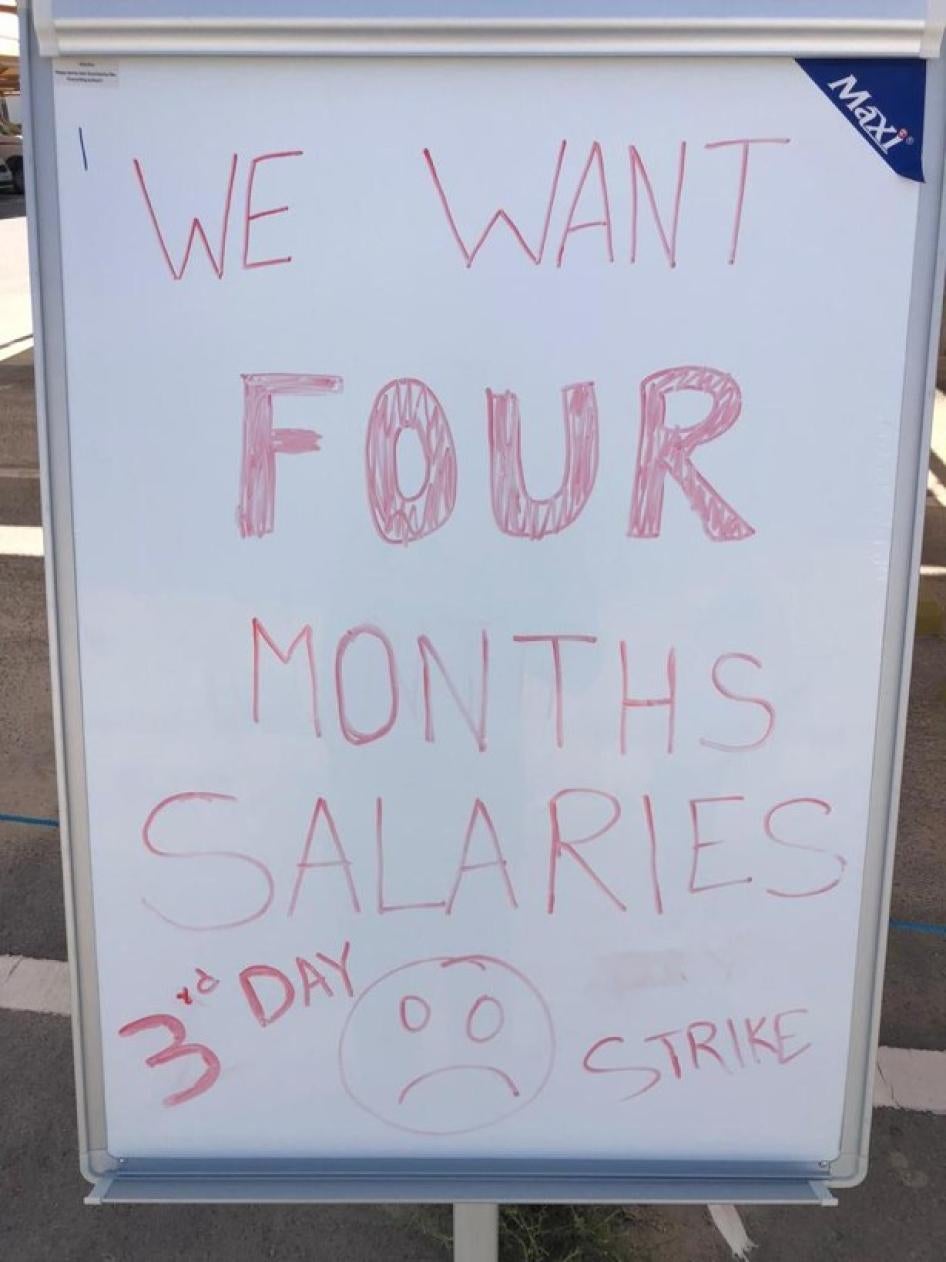

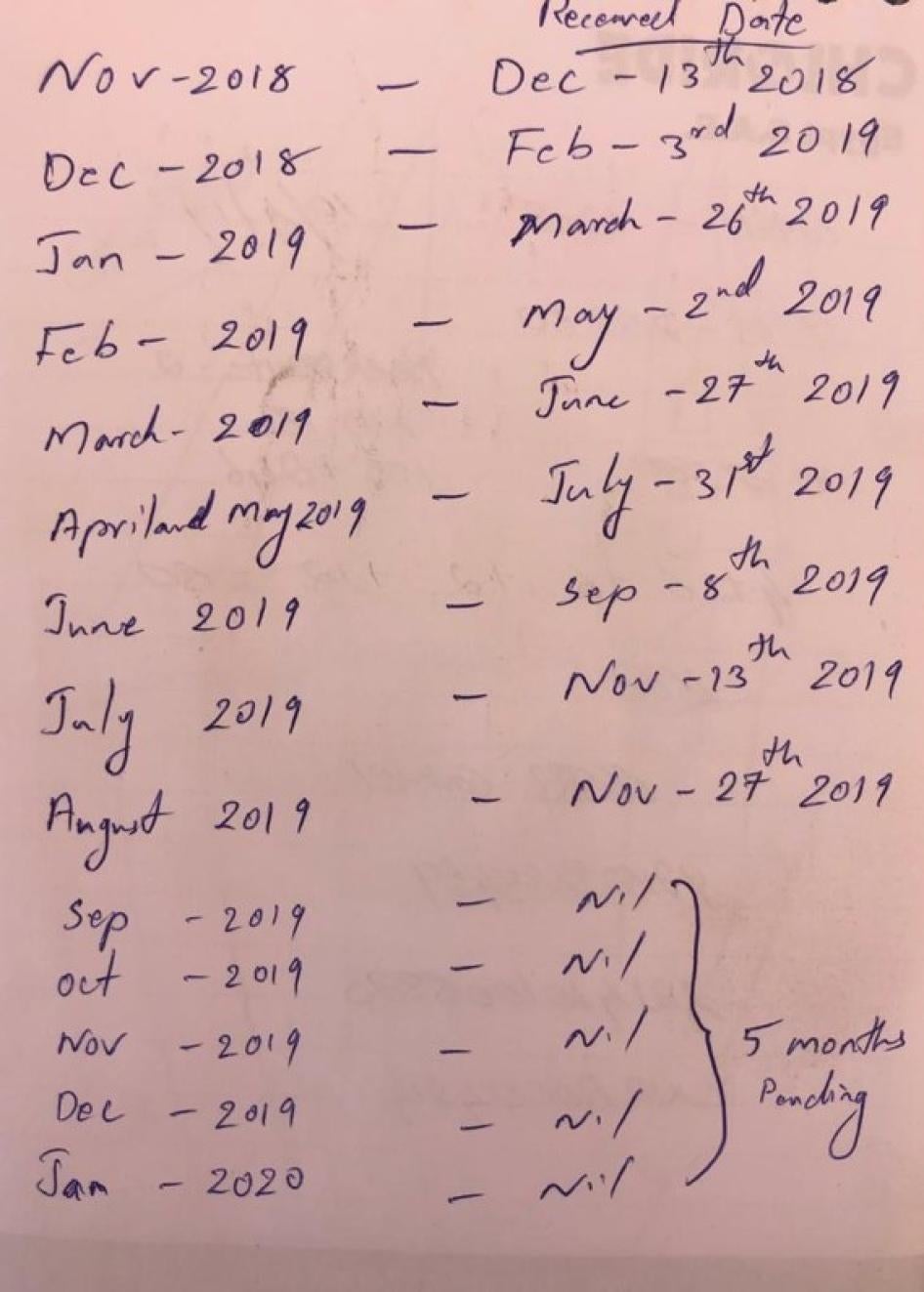

Upon arriving in Doha in June 2019 however, Henry’s excitement dissipated. The first month, Henry’s employer had no work for him, which meant there would be no pay. The second month, his employer withheld his salary as a ‘security deposit’. To feed himself and his family, Henry was forced to take on more loans. Eventually, in September, he was paid for the first time. But his salary was shockingly low at only 830 Qatari riyals ($228).

For two months, during which Henry performed backbreaking work as a plumber for up to 14 hours a day at a hotel in Lusail city, his employer paid him 30 percent less than he was owed in basic wages. “Where was my full salary? Where was the overtime money and food allowance I was owed? I was shocked, but not alone - the company had cheated 13 Kenyan workers along with me,” said Henry.

While Henry was battling the bitter realities of working in Qatar as a migrant worker, “Samantha” was getting ready to leave Qatar after being cheated of her basic and overtime salaries for two years.[2]

Between December 2017 and December 2019, Samantha, a 32-year-old Filipina, either scrubbed bathrooms or swept the food court in an upscale mall in Doha. She told Human Rights Watch that her employer made her work 12-hour shifts, had her and her colleagues’ passports confiscated and banned them from leaving the company-provided accommodations for anything other than work.

In 2017, when she had made the decision to leave behind her two toddlers to work in Qatar, she had agreed to work for a monthly salary of 1,800 Qatari riyals ($494). The contract stated that for each hour of work above 8 hours a day, she would be paid 25 percent more than her basic wage. In reality, Samantha worked for 12 hours a day and was paid 1,300 Qatari riyals ($357) a month with no compensation for the overtime work she performed. When she asked why her salary was less than promised and complained that the 25-day salary delays caused her family in the Philippines to starve, her employer told her “to focus on her work silently.” He also withheld her first month’s pay, saying it was “a measure of good faith, a security deposit.” A week before her return to the Philippines, she said her employer informed her he would not be paying her what he owed her in end-of-service payments, and would use her first month’s salary to buy her return flight ticket to the Philippines, instead of paying for the ticket himself as promised in her contract.

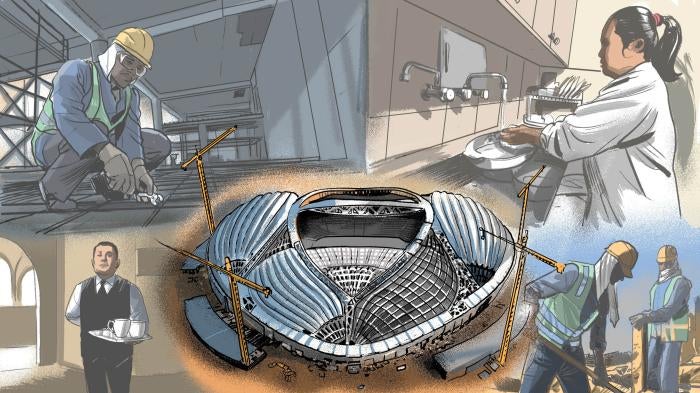

Henry and Samantha’s stories illustrate the wage abuses employers afflict on migrant workers in Qatar today. Qatar’s economy is reliant on some 2 million migrant workers - making up around 95 per cent of its total labor force - who come from countries like India, Nepal, the Philippines, Bangladesh, Kenya, and Uganda to seek better income opportunities. These migrant workers are responsible for building the stadiums, transportation, and hotels for the upcoming FIFA World Cup 2022, and they are almost solely responsible for building the infrastructure and powering the service sector of the entire country. In exchange for this labor, they are only guaranteed a minimum wage of 750 Qatari riyals ($206) per month, which, when paid on time and in full, is barely enough for many workers to pay back recruitment debts, support families back home, and afford basic needs while in Qatar.[3] On top of this, employers’ wage abuses leave many in perilous circumstances.

Human Rights Watch spoke to 93 migrant workers working for 60 different employers and companies between January 2019 and May 2020, all of whom reported some form of wage abuse by their employer such as unpaid overtime, arbitrary deductions, delayed wages, withholding of wages, unpaid wages, or inaccurate wages.

The findings in this report show that across Qatar, independent employers, as well as those operating labor supply companies, frequently delay, withhold, or arbitrarily deduct workers’ wages. Employers often withhold contractually guaranteed overtime payments and end-of service benefits, and they regularly violate their contracts with migrant workers with impunity. In the worst cases, workers told Human Rights Watch that employers simply stopped paying their wages, and they often struggled to feed themselves. Taking employers and their companies to the Labour Relations department or the Labour Dispute Resolution Committees is difficult, costly, time-consuming, ineffective, and can often result in retaliation. Workers often describe taking legal action as a “Catch-22” situation - indebted if you do, indebted if you don’t.

The Covid-19 pandemic has amplified the ways in which migrant workers’ rights to wages have long been violated. While none of the wage-related problems migrant workers are facing under Covid-19 are novel — delayed wages, unpaid wages, forceful terminations, repatriation without receiving end-of-service benefits, delayed access to justice regarding wages, arbitrary deductions from salaries — since the pandemic first appeared in Qatar, these abuses have appeared more frequently.

While each migrant worker had a unique story, the wage abuses they face reflect a pattern of abuse driven and facilitated by three key factors: the kafala (sponsorship) system, a migrant labor governance system in Qatar; deceptive recruitment practices both in Qatar and in workers’ home countries; and business practices including the so-called ‘pay when paid’ clause, which requires the subcontractor to delay payments to workers and leaves migrant workers vulnerable to payment delays in supply chain hierarchies.

Kafala at the Heart of Migrant Worker Abuse

At the heart of enabling wage abuse lies the kafala (sponsorship) system, which ties migrant workers’ visas to their employers. This leaves workers dependent on their employers for their legal residency and status in the country, placing them in a position of vulnerability that employers can, and often do, take advantage of.

In 2017, Qatar committed to abolishing the kafala system.[4] And while it has since introduced some measures that have served to chip away at kafala, employers are still responsible for securing, renewing, and cancelling residency permits for migrant workers, and are thus still able to severely restrict workers’ ability to change jobs. The kafala system grants employers unchecked powers over migrant workers, allowing them to evade accountability for labor and human rights abuses, and leaves workers beholden to debt and in constant fear of retaliation. In Qatar, where workers, especially low-paid laborers and domestic workers, often depend on the employer not just for their jobs but also for housing and food, and where passport confiscations, high recruitment fees, and deceptive recruitment practices are ongoing and largely go unpunished, the kafala system continues to drive abuse, exploitation, and forced labor practices.

Deceptive Recruitment Practices Leave Workers Indebted and Vulnerable

The Qatari government had previously stated that the illegal yet pervasive issue of migrant workers’ paying their own recruitment fees is not a Qatari problem and is one for workers’ countries of origin to address. However, the profits are not limited to recruiters in countries of origin; Qatari companies, employers, and recruiters benefit when workers are forced to pay their own recruitment fees. Companies in Qatar increase their competitiveness by outsourcing the payment of recruitment fees to contractors and subcontractors, who eventually pass the buck to workers who end up paying their recruitment fees themselves. Thus, migrant workers like Henry, and 71 others in this report, told Human Rights Watch that they are already indebted when they arrive in Qatar, having paid between $693 to $2,613 in recruitment fees to secure such jobs. Ultimately, they found themselves compelled to work for months without pay, because they have no choice but to stay with only the promise of being paid. This indebtedness increases the ‘power’ of companies and employers over employees, making them even more likely to get away with abusing employees without accountability.

Harmful Business Practices Punish Workers Most

Some companies in Qatar deliberately withhold, delay, or deny workers’ wages for additional profits. But other companies, typically small and medium-sized enterprises in the construction industry where long and often complex subcontracting chains are the norm, may be unable to pay workers in full and on time because of payment disruptions higher up the chain. These disruptions can lead to insolvency and encourage the commonly practiced, yet unofficial, policy of paying onwards only when paid. Such problems are not unique to Qatar. But while many other countries have adopted policies and laws that aim to tackle the problem of unpaid wages for workers as a result of “pay when paid” policies, Qatar has yet to do so. Moreover, construction is the largest job sector in Qatar, and thousands of migrant workers have been left penniless due to subcontractors’ insolvency issues higher up the supply chain.

Wage Protection System Not Worth the Name

Wage abuses are amongst the most common and most devastating violations of migrant workers’ rights not just in Qatar, but across the Gulf region, where various iterations of the kafala system exist and where construction is often amongst the largest industries. In 2015, following the United Arab Emirates’ lead in 2009, Qatar installed a Wage Protection System (WPS), meant to ensure migrant workers are paid in a timely and accurate fashion. Today, different versions of the WPS exist in all the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries except Bahrain. Despite the WPS being advertised as an effective mechanism to address wage abuses, workers’ wage violations remain prevalent across the region.

In Qatar, the Wage Protection System is indeed a misnomer for a software that, in reality, does little to protect wages, and can be better described as a wage monitoring system with significant gaps in its oversight capacity. At best, the WPS attempts to monitor workers’ salaries and raise red flags when payments are inaccurate or delayed - at times, even these tasks are not effectively performed.

In 2018, Qatar established the Labour Dispute Resolution Committees, designed to speed up the litigation process and shorten the time it takes to resolve labor disputes. That same year, it also passed a law establishing the Workers' Support and Insurance Fund, designed to ensure workers receive their unclaimed wages in cases where the Labour Dispute Resolution Committees ruled in their favor and where their company could not or would not pay them.

However, according to the findings of this report and a September 2019 Amnesty International report, the Labour Dispute Resolution Committees remain slow, inaccessible, and ineffective. As long as migrant workers continue to lack control over their own immigration status, and are severely restricted in their ability to work with another employer in order to financially support themselves to remain in the country, the right to pursue compensation is futile. Meanwhile, the Workers' Support and Insurance Fund, which is intended to protect workers from the impact of overdue or unpaid wages, was established in 2018 and only became operational earlier this year.

Qatar has ratified five of the eight International Labour Organization (ILO) conventions setting out core labor standards, yet Qatar is failing to protect workers’ wages. The ILO has recommended that countries such as Qatar should consider measures to protect wages including prompt payment legislation; banning unofficial ‘pay when paid’ policies; and introducing rapid adjudication, project bank accounts, subcontract payment monitoring systems, and joint liability systems.

The abuses Samantha faced in Qatar cannot be undone, but the wages she was cheated of can still be paid to her, and her employer can still be held accountable to prevent him from cheating others. As for Henry, his journey to Qatar is hardly a year old. The Qatari government still has time to hold his employer to account, reinstate his original contract, and pay back his outstanding wages and recruitment fees.

There are less than 1,000 days left for the first World Cup football to be kicked off a shiny, brand new stadium in Qatar, built on the hard labor of migrant workers. That leaves the Qatari authorities with just enough time to kick off wage reforms swiftly and efficiently before the first football players and fans begin arriving.

Methodology

Human Rights Watch conducted the research for this report between January 2019 and May 2020. Researchers conducted detailed interviews with 93 migrant workers from 60 different companies and employers, whose conditions are the focus of this report – 11 of these workers are female domestic workers whose salary payment conditions slightly differ from other migrant workers. Migrant workers described their migration processes to Qatar, including the contractual information they had before migrating and the work conditions they found upon arrival. They gave accounts of their experiences of working in Qatar with delayed, inaccurate, or unpaid salaries, as well as any attempts to seek redress.

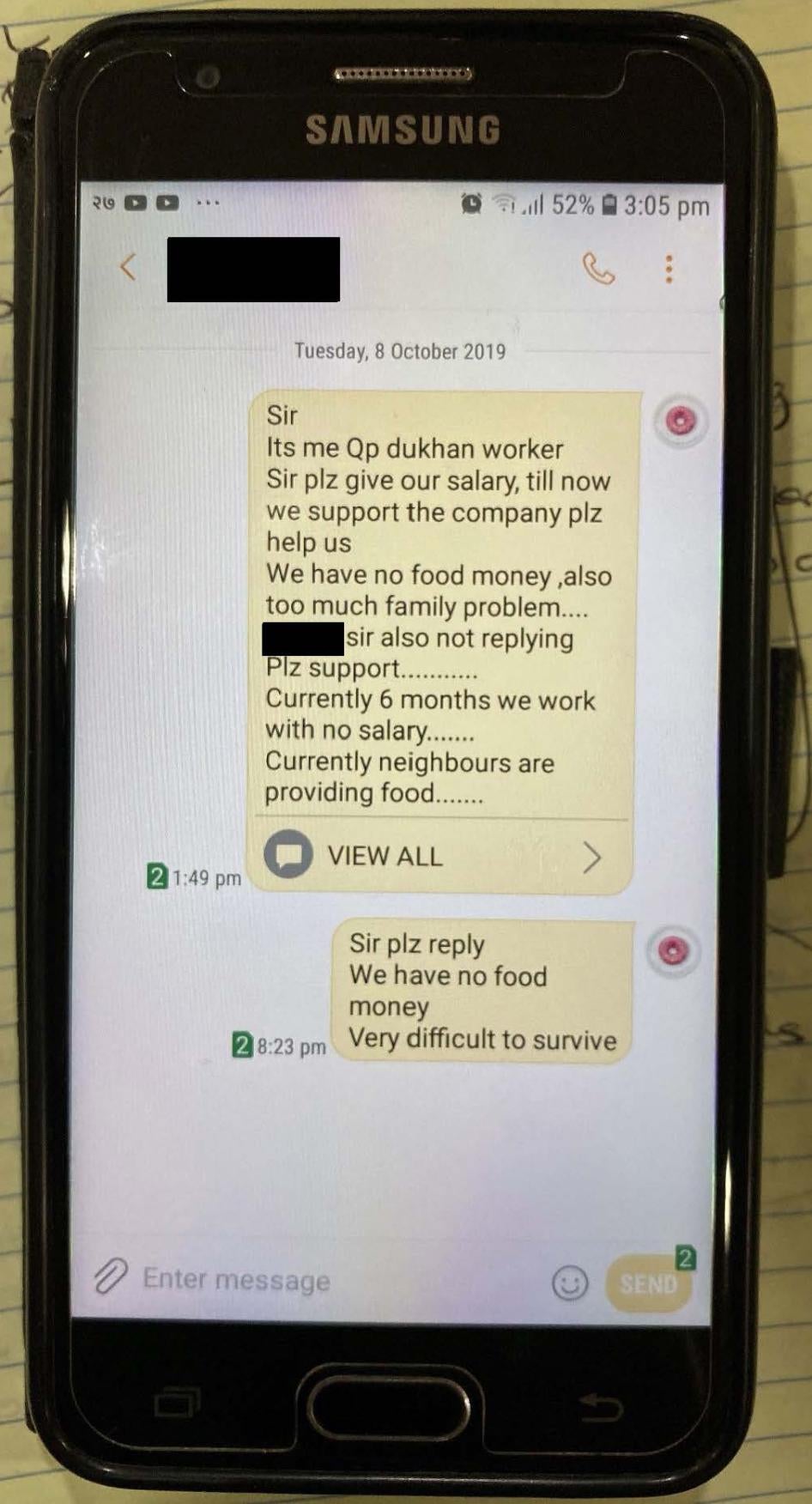

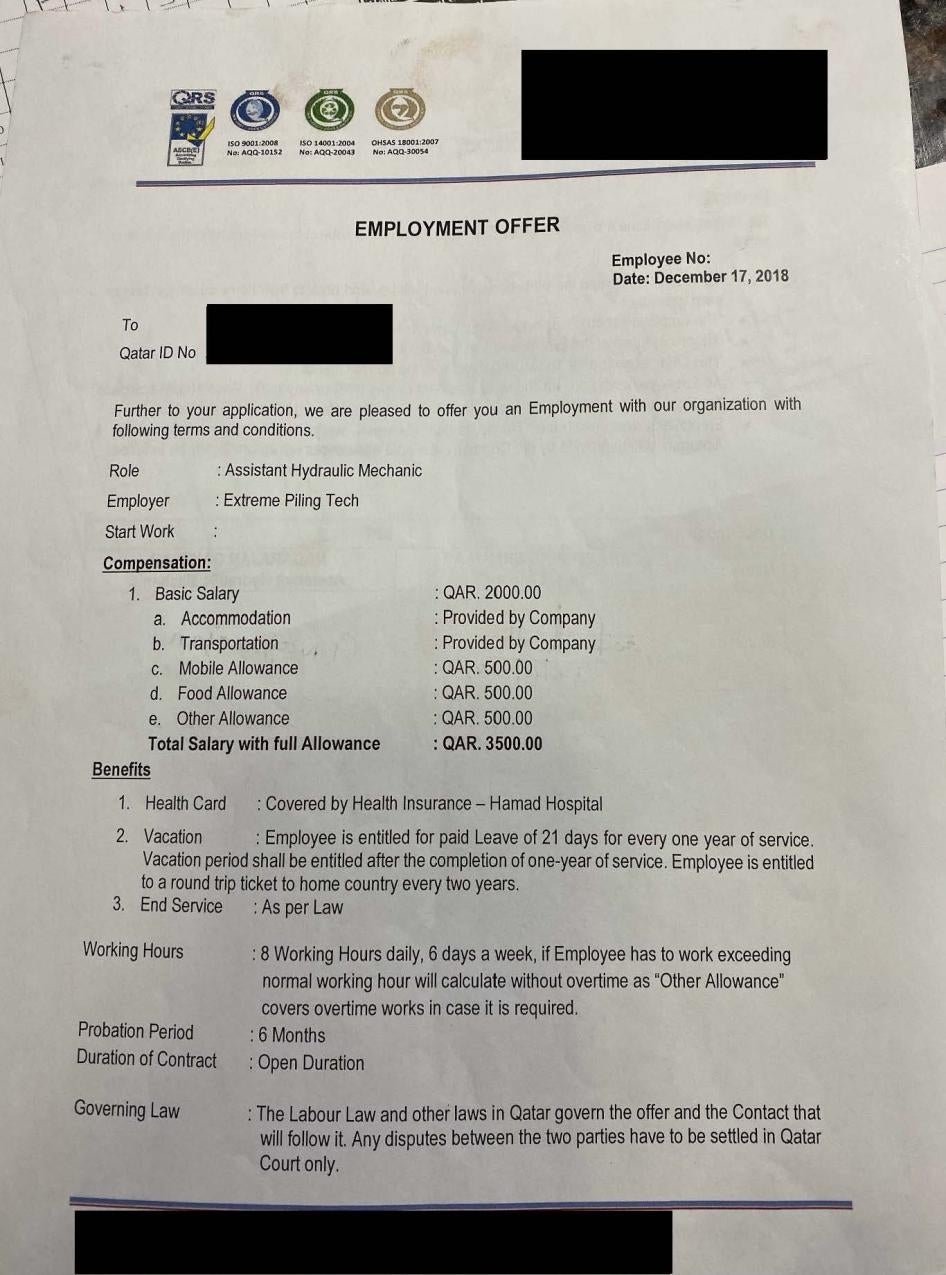

Human Rights Watch reviewed the text of more than 10 migrant workers’ documents in cases relating to underpayment and contract substitution and four workers’ company memos relating to delayed payments. Researchers also saw text message conversations from four workers to their employers, discussing late payments and the consequent lack of money for food.

Researchers interviewed workers in a wide variety of locations, and at various times of day, in Qatar. Some interviews were conducted over the phone, especially with workers who have returned to India, Kenya, Pakistan, and the Philippines. Researchers met migrant workers in various public spaces. As workers live, work, and congregate in crowded conditions with limited private space, Human Rights Watch could not conduct one-on-one interviews in completely private settings. The workers interviewed are employed by diverse employers in various fields and include managers, surveyors, and engineers, as well as laborers and domestic workers. Despite these differences, workers reported strikingly similar forms of abuse. Human Rights Watch interviewed workers in English, as well as Hindi, Urdu, and Arabic. In each case, Human Rights Watch explained the purpose of the interview, how it would be used and distributed, and obtained consent to include their experiences and recommendations in the report. None of the interviewees received financial compensation or other incentives for speaking with Human Rights Watch.

Most of the workers Human Rights Watch interviewed expressed fear for their jobs and their immigration status if their employers found that they had spoken about their working conditions to a human rights organization. Researchers interviewed them on the condition that Human Rights Watch would not use their names, and many requested that the name of the company that employed them not be mentioned. Their requests reflect the degree of control employers hold over workers, and workers’ fear of retaliation and abuse should they attempt to exercise their rights.

Human Rights Watch sent letters to 11 companies in labor supply and construction sectors requesting their input on migrant workers’ payment policies in Qatar. As of August 1, 2020, Human Rights Watch has received no response(s) from these companies.

Researchers also spoke with representatives of the Qatar National Human Rights Committee (NHRC), a government-funded human rights organization in Doha, as well as the International Labour Organization (ILO).

Researchers also interviewed professors who are experts on migration policy, migration ethics and human rights, and other human rights researchers, and reviewed relevant academic literature, news articles, and reports published by NGOs and international institutions.

The report uses an exchange rate of 1 Qatari Riyal (QR), also written as riyal in this report, equal to US$0.27; 1 Kenyan Shilling equal to QR0.03 or $0.009; 1 Philippine Peso equal to QR0.07 or $0.02; 1 Indian Rupee equal to QR0.05 or $0.01; 1 Nepalese Rupee equal to QR0.03 or $0.008; except where a historical exchange rate is warranted.[5]

Lastly, Human Rights Watch sent letters summarizing the findings of this report, requesting an official response and providing a detailed set of queries, to relevant officials at the Ministry of Interior and the Ministry of Labor, as well as to FIFA and the Supreme Committee for Delivery and Legacy (SC). This correspondence is affixed as an appendix to this report, and relevant sections are directly incorporated into the body of the report.

Key Recommendations

To the Qatari Shura Council and Council of Ministers

- In line with stated commitments, abolish the kafala system in full, making the state the sponsor for migrant workers, and ensuring that workers’ entry, residence and work visas are not tied to employers, and ensuring that workers are not ever required to obtain employer permission to change employers or leave the country, and remove absconding penalties.

- Amend the labor law to guarantee workers’ right to strike, free association and collective bargaining, including for migrant workers and domestic workers.

- Amend the labor law to include domestic workers receive the same protections as other workers.

- Immediately announce and implement a non-discriminatory minimum wage for migrant workers, including calculating an hourly minimum wage, that equals a living wage that allows workers a decent standard of living for themselves and their families. A committee should periodically review the minimum wage levels so that it guarantees a living wage.

To the Qatari Labor Ministry

- Increase the capacities of the WPS Unit, the Labour Relations department, and the Labour Dispute Resolution Committee so that they can more effectively monitor and resolve cases of wage abuses in a speedy, and compassionate manner for workers.

- Improve the workings and systems of the WPS so that Salary Information Files are more detailed and comprehensive; alerts are dealt with in a strict manner; and ensure that companies are providing workers with timesheets and itemized pay slips; finalize the process of e-contracts to ensure that workers’ contract details including basic wages are accurately and automatically recorded in the WPS.

- Monitor and ensure that companies are not doing business with recruitment agencies and subcontractors, in Qatar and abroad, that charge workers fees or costs for travel, visas, employment contracts, or anything else. Ensure that any recruitment costs, fees or charges that workers incur in order to migrate are reimbursed to them by their employers.

I. Background

Qatar, one of the world’s wealthiest states on a per capita basis, is almost entirely reliant on some 2 million migrant workers who represent around 95 per cent of the country’s total labor force and who are primarily employed in the construction and service industries.[6] Without such workers, many of whom come from some of the world’s poorest countries in search of better work opportunities, the country would grind to a halt.[7]

A decade ago, in December 2010, Qatar won the right to host the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) World Cup 2022.[8] Qatar’s initial estimates for infrastructure expenditure for the world’s largest sporting event were as high as US$220 billion.[9] According to the International Trade Union Conference’s Frontline Report in 2015, this set up Qatari and international infrastructure companies to expect a tidy sum of $15 billion in profits.[10] Since then, it is likely that the costs for the infrastructure of the World Cup will have increased. The Qatari government awarded 11 multibillion-dollar contracts in 2014 to international and local companies for the construction of the Doha Metro.[11] Seven new state-of-the-art stadiums with advanced open-air cooling technology are being built from scratch for the 2022 event, the majority of which are still under construction.[12] The construction of the gleaming Hamad International Airport, sprawling over 5,400 acres of land, with two of Asia’s longest runways, took over a decade and cost $16 billion.[13] As these investments grow, so do profits.

By contrast, many of the migrant workers laboring to build the stadiums, the metro system, the highways, parking lots, bridges, hotels, and other infrastructure needed to host the millions of visitors the World Cup event is expected to attract, are paid a pittance. So are the cleaners, restaurant staff, security guards, drivers, and stewards who will shoulder the hospitality sector’s efforts to accommodate the influx of people expected to visit the country.

Currently, a migrant worker’s basic minimum wage in Qatar is a meager QR750 ($206) per month, which, when paid on time and in full, is hardly enough for many workers to pay back recruitment debts, support families back home, and afford basic needs while in Qatar.[14]

‘Kevin’, a 35-year-old security guard from Kenya whose family back home is harassed on a daily basis for the loan Kevin has not paid back yet, explains: “I paid 120,000 Kenyan Shillings [$1,123] as recruitment fees for a job Qatar in 2017. At my salary and the overtime payment promised in the contract, I should have been able to pay it back in a year. But you see, the company delays payments, and never pays for overtime work, so I take more loans, to feed myself and my family back home. I keep going further and further in debt. Sometimes I think there is no way out. I will be trapped here working forever.”[15]

Unfortunately, many workers who came to Qatar hoping to earn enough to pay medical bills for sick parents, pay for children’s school fees, save up money to get married or build homes in their countries of origin have found themselves worse off than when they left their own countries. Too often, migrant workers suffer wage abuses at the hands of their employers, including delayed wages, punitive and illegal wage deductions, and, most debilitating yet all too common, months of unpaid wages for long hours of grueling work.

Wage abuse is one of the most significant problems facing migrant workers in Qatar and across the Gulf region.[16] Apart from being forced to work long hours by employers, living in cramped quarters, paying off their debts, and being beholden to their sponsors for their jobs, food, housing, residence permits and visas, many of Qatar’s migrant workers fight a persistent battle against wage abuse. Each of the 93 migrant workers interviewed for this report has, at least once, faced issues such as delayed wages, unpaid overtime, withholding of wages, arbitrary deductions, inaccurate or unpaid wages, or some other form of wage abuse at the hands of employers in Qatar.

‘Yoofi’, a 33-year-old security guard from Ghana, said his employer has been delaying his monthly salary of QR 1,000 ($275) since he began working in Qatar in June 2019.[17] “We have not been paid in 11 months. Every month they say the salary is delayed and so we borrow money from friends, we take credits in the market for groceries. Even then all we can afford to eat is boiled rice. And because of all the borrowing and credit we have no money to send home to our families.”[18]

Human Rights Watch also found cases of delayed wages for workers with higher salaries. ‘Alvin,’ a 38-year-old human resources manager at a construction company in Qatar which has been contracted for the civil, water, and masonry work on the external part of a stadium for the FIFA World Cup 2022, reported that his monthly salary of QR4,500 ($1,235) has been delayed for up to four months at least five times in 2018 and 2019.[19] “I am affected because due to the delayed salary I am late in my credit card payments, rent, and children’s school fees. I borrow money from the bank whenever payments are delayed. Even right now my salary is two months delayed. It’s the same story for all the staff on my level and even the laborers. I can’t imagine how the laborers manage, they can’t take loans from the bank the way I can,” said Alvin.[20]

In the majority of cases where Human Rights Watch documented wage abuses, two immediate issues that arose were hunger and the lack of money to send home to families. ‘Sanyu’, a security guard with six children depending on him back home in Uganda, “came to Qatar in search of a better life” in September 2019.20F[21] His contract promised he would be paid QR1,200 ($329) a month, but between September 2019 and December 2019, he was only paid for one month of work; for the remaining three months, his employer gave him QR250 ($68) a month in cash as a food allowance. “They think that’s enough money to survive a month in Qatar? It is not. I starve for food, my family back in Kenya starves for food. I am surviving only because Ugandan workers helped me out for food money,” said Sanyu. “These contracts we signed and the jobs that came with them are like swords over our heads. When we ask our employers when our salary is coming they say next week, but it’s already been delayed 10 times.”[22]

|

Type of Wage Abuse |

Explanation |

Recorded Instances |

|

Delayed or Unpaid Wages |

Employers consistently delaying monthly wages, sometimes to the point of non-payment of wages. These are often company wide. |

59 |

|

Lack of Overtime Payments |

If workers are performing more than 8 hours of work a day, they should be compensated at a higher rate for the extra hours. In most recorded instances, employees are not paid at all for the extra hours. |

55 |

|

Contract Substitution |

Workers sign employment contracts in countries of origin that promise a certain salary but upon arrival in Qatar find that they are met with a new contract with a lower salary. |

13 |

|

Lack of departure payments |

Migrant workers in Qatar are promised end-of-service benefits, salary in lieu of unused vacation days, and a ticket home at the of their contract. Often these are not paid. |

20 |

|

Underpayments of basic payments |

Employers consistently paying lower than contractually stipulated amounts, arbitrary deductions, or employers not having enough assignments for workers |

35 |

|

Payment of recruitment fees |

It is employers who should be paying recruitment fees for migrant workers, along with their airfare to Qatar, instead in too many cases, workers are taking personal loans to make these payments |

72 |

The above table depicts the various types of wage abuses migrant workers in Qatar face; the numbers of recorded instances are from a pool of 93 migrant workers from over 60 different employers and companies. © 2020 Maham Javaid/Human Rights Watch

The Framework for Enabling Unpaid Wages

A combination of factors in Qatar and other Gulf countries provide for an environment where migrant workers seeking better opportunities suffer wage abuses for months, and sometimes years, of service, often leaving them in far more dire straits than when they initially embarked on their migration journey. They include an exploitative and restrictive labor governance system; the illegal yet far-too-common practice of migrant workers paying exorbitant recruitment fees to secure jobs in countries across the Gulf region; pay-when-paid policies which allow subcontractors to delay payments to workers until they receive payments from contractors, and the lack of migrant workers’ access to effective avenues of redress.

Kafala sponsorship system

The kafala (sponsorship) system, various iterations of which exist across the region but in particular Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Jordan, and Lebanon, grants employers responsibility for, and therefore control over, migrant workers in at least one of five ways: their entry into the country of destination, renewal of their residence permits and work visas, termination of employment, transfer to another employer, and exit from the country of destination.[23]

In Qatar, at present, a worker must be sponsored by an employer in order to enter the country and mostly remains tied to that employer throughout their stay. Employers are responsible for renewing and canceling workers’ residence permits and work visas, leaving workers dependent on their employers for their legal residency and status in the country. Employers’ failure to secure residence permits for workers in their employ, despite it being a legal obligation to do so within 90 days of a migrant worker’s arrival, leaves workers under threat of arrest and deportation. While an employer can cancel a migrant worker’s residence permit at any time by initiating repatriation procedures, a worker who leaves his employer without permission can be punished with imprisonment, fines, deportation, and arrest for “absconding.”[24]

Human Rights Watch research has shown that the serious and systemic abuse of migrant worker rights in Qatar often stem from the kafala system in conjunction with other harmful practices such as the routine confiscation of worker passports by employers, and the payment of recruitment fees by workers, which keeps them indebted for years. Alongside the prohibition on worker strikes, these factors have contributed to circumstances of forced labor, making it virtually impossible for workers to leave even abusive employers, despite often suffering non-payment of wages, long working hours, dangerous working conditions, and sub-standard housing conditions.

Despite recent reforms introduced to better protect migrant workers’ rights, the kafala system remains an inherently abusive system for migrant workers. Measures taken so far have failed to protect workers from abusive situations, and situations of forced labor. Qatar for instance, abolished the exit permit for most migrant workers, in which employers had the right to grant or refuse a migrant worker’s ability to leave the country.[25] However, in most cases, migrant workers cannot change jobs before the end of their contracts without their first employers’ written consent.[26]

The kafala system essentially provides employers unchecked powers to wield over migrant workers, leaves workers to live under constant fear, and prevents them from formally complaining to authorities. Employers, for instance, exert control over their workers by routinely confiscating their workers’ passports, despite this being illegal, and by threats to report them to the police as “runaways.”

In October 2017, Qatar committed to abolish the kafala system, among other labor reforms, as part of its technical cooperation agreement with the International Labour Organization (ILO) and to stop a complaint documenting Qatar's failure to uphold the 1930 Forced Labour Convention and the 1947 Labour Inspection Convention.[27] Under pressure, Qatar agreed to replace kafala with a system of government-issued and controlled visas for workers. Under this commitment they also agreed to lift restrictions on migrant workers’ ability to change employers and exit the country without needing an exit permit from their sponsor, ensure that the domestic worker law is implemented and reviewed by the ILO, and that recruitment practices are improved through better monitoring and regulation and the implementation of the Fair Recruitment guidelines in three migration corridors. However, at the time of writing, apart from reforms to the exit permit, reforms to the wider kafala system had still not been issued.

To date, migrant workers are banned under Qatari law from joining unions and participating in strikes.

Recruitment Fees: Drowning in Debt

“If I had known my life in Qatar would be like this, I would never have come,” said ‘Isaac’, 33, a Kenyan plumber in Qatar.[28] Isaac feels compelled to remain in Qatar, working for an employer that pays him unfairly and arbitrarily because, like thousands of other migrant workers, the $1,125 recruitment fees he paid to obtain a job in Qatar trapped him in debt even before he arrived in the country.

Of the 93 workers interviewed for this report, 77 workers told Human Rights Watch that they are in debt from paying recruitment fees to agents in their home countries. These workers reported paying fees ranging from $693 to $2,613, such fees vary depending on nationality, with Bangladeshis typically bearing the biggest burden, and workers from the Philippines paying the lowest amounts.[29] Qatar is not the only country where migrant workers face recruitment fees. Other reports have documented a comparable range of recruitment fees that workers pay to work across the Gulf from $400 to $5,200.[30] Migrant workers told Human Rights Watch that they sold valuable assets, mortgaged family homes, or borrowed large amounts of money from private moneylenders at exorbitant interest rates to cover the recruitment fees. But the jobs they get are commonly different from, and pay less than, the ones they are promised.

The Qatari government is aware of the debts migrant workers incur on the road to Qatar and have forbidden companies from levying recruitment costs on workers.[31] However, the law does not require employers to reimburse employment-related recruiting fees that workers have incurred and does not address the problem of Qatari employers or recruiters who work with foreign agents to charge workers fees in their home countries.[32]

In 2012, the Qatari government had stated that the issue of recruitment fees, while grave, is not a Qatari problem where there are procedures against such agencies.[33] The problem, they claim, is for workers’ countries of origin to address.[34] Since then, Qatar has signed 40 bilateral labor agreements and 19 Memoranda of Understanding with countries of origin to protect migrants from paying exorbitant recruitment fees. The profits are not limited to sending countries: Qatar greatly benefits when workers are forced to pay their own recruitment fees. For example, a 2011 World Bank study on migration from Nepal to Qatar estimated that recruitment agents in Qatar receive between US$17 million and $34 million in commissions from Nepal each year.[35] Qatar has an obligation to prohibit recruitment agencies that are operating in the country from charging fees and to actively prevent Qatari companies from relying on recruitment agencies who demand fees regardless of where the transaction takes place.

According to an ILO white paper, companies in Qatar circumvent local labor laws and increase their competitiveness by outsourcing the payment of recruitment fees to contractors and subcontractors.[36] Contractors can omit recruitment costs in order to minimize expected expenses in tenders they submit bids for to companies.[37] They then pass the buck to recruitment agencies in countries of origin, which charge migrant workers to pay for their own recruitment costs. The ILO also found that workers are often forced to pay additional inflated fees to the local agency. These fees are partly used to provide kickback payments to the employing company personnel and placement agencies in Qatar.[38] These kickback payments are often a way that private agencies in countries of origin are able to secure labor supply contracts.

Recruitment fees play a large part in keeping debt-laden workers working for abusive employers. When workers owe thousands of dollars in recruitment fees, cannot switch jobs without employer approval and without having to go through the process of paying the fees all over again, and do not have custody of their own passports, the situation can amount to forced labor.[39]

How Supply Chain Payment Policies Punish Workers Most

Some companies in Qatar withhold, delay, or deny worker’s wages for additional profits. But other companies, typically small and medium-sized enterprises in the construction industry where long and often complex subcontracting chains are the norm, may be unable to pay workers in an accurate and timely fashion because of payment disruptions higher up the chain that lead to insolvency and encourage businesses paying onwards only when paid. Some of these subcontracting companies, while based in Qatar, may be owned and staffed by migrants from low-income companies. Such problems are not unique to Qatar and are inherent in the structure and operation of the construction industry worldwide.[40]

A 2018 Engineers Against Poverty three-part report focused on addressing the prevalent issue of delayed and unpaid wages of migrant construction workers in Gulf countries. It looked at the ways current systems in the GCC were failing to protect the wages of vulnerable workers and recommended measures through which to ensure workers have an additional source of payment to fall back on if their immediate employer cannot – or will not – pay their wages.[41] They reported that wage delays exist because “under the current business model, extensive subcontracting and outsourcing of labor has increased the distance that interim payments have to travel to reach the immediate employers of the workforce, which are often small firms with limited financial resources, unable to pay wages until they have received payment for the work already completed.”[42]

The report describes the practice of “pay when paid”, which is commonly incorporated into contracts across the Gulf region in the absence of a 30-day payment cycle imposed by law, as one where contractors are not legally obliged to pay their subcontractors until they have received payment from the client. According to the report, those most affected are often small firms with limited financial resources that cannot pay wages until they have received payment for the work already completed, leaving migrant workers in their employ, who are at the very bottom of the subcontracting hierarchy, the most vulnerable.

In anticipation of the World Cup 2022, Qatar has seen a spurt in the growth of labor-only supply companies.[43] Often, these small and medium-sized companies do not possess sufficient funds to pay wages if they themselves suffer delays in payment. Often times, the report states, “while subcontractors and labor suppliers take the blame when it is discovered that wages are delayed, it is seldom considered that they may not have the funds to pay on time.”[44]

“I feel bad for them, these are my people after all, they are Nepalis, and I haven’t paid their full salary in 9 months,” said ‘Priya’, a Nepalese owner of a medium-sized labor supply company.[45] “I haven’t been paid by my clients, which means I don’t have money to pay my workers. I paid basic wages to as many workers as I could.” Priya said she had been supplying workers to a construction company that she wished not to name and in December 2019 she had not received payments for work completed for nine months. “If I am not paid, how can I pay my workers?” she said.[46] She told Human Rights Watch that she has many entrepreneur friends similarly stuck.

Priya told Human Rights Watch that she is on friendly terms with the owner of the construction company that hired the workers she employs. This owner allegedly confided in Priya about how he himself had not been paid for 2 years. The construction company, a subcontractor, is expecting payments from a large international construction company, the main contractor, which is in turn waiting for payments from a Qatari public entity.[47]

Yet habitual insolvency does not let companies like Priya’s off the hook. On the contrary, it underscores the risk to employees when a business model depends on payment of upstream contracts, which are regularly delayed, to cover employee salaries. Employers should ensure that they have the means to pay all their workers on time given a realistic timeline for when they can expect payment on contracts owed to them. To provide additional protection for wages from Qatar’s trickle down “pay when paid” supply chain, Qatar could consider extending the liability for wages beyond the immediate employer in subcontracting chains. According to Engineers Against Poverty, if a subcontractor does not pay a labor supply company, as in Priya’s case, then the main contractor, in this case, the Qatari public entity, could be held liable for this debt. This could serve two advantages: not only would it ensure workers are being paid in full and on time, but major contractors would also take greater responsibility for their subcontractor’s actions, and this would weed out non-reliable subcontractors.

Qatar’s Efforts to Tackle Unpaid Wages

In 2015, in an effort to tackle the prevalent issue of wage abuse, Qatar introduced amendments to its labor law and unveiled the much-touted Wage Protection System (WPS), an electronic salary transfer system designed “to ensure that employers are obliged to pay the wages of workers who are subject to the Labor Code within the prescribed deadlines.”[48] The WPS was originally implemented by the UAE in 2009 and today all the GCC countries except Bahrain have rolled out different versions of the system.[49]

In October 2017, in response to a forced labor complaint levelled against the country in 2014, Qatar agreed to a three-year technical cooperation agreement with the International Labour Organization in which they agreed to improving wage protection; enhance labor inspections and occupational safety and health systems; replace the kafala system with a system of government issued and controlled visas for workers (see above on kafala sponsorship system); step up efforts to prevent forced labor, and promote workers voice.[50]

On wage protection, Qatar committed to enhancing the Wage Protection System (see below) and ensuring that sanctions for non-payment of wages are enforced; establishing a wage guarantee fund; adopting a non-discriminatory minimum wage; and expanding effective coverage of the WPS to cover small and medium enterprises, subcontractors and eventually domestic workers.

Since then, and to great fanfare, Qatar has introduced several piecemeal reforms.[51] In regards to wage abuse, they set a temporary minimum wage for migrant workers, set up new Labour Dispute Resolution Committees designed to give workers an easier and quicker way to pursue grievances against their employers, and passed a law to establish a Workers’ Support and Insurance Fund, partly designed to make sure workers are paid unclaimed wages when companies fail to pay.[52]

Yet migrant workers remain vulnerable to abuse and exploitation. The temporary minimum wage of QR750 ($206) per month is often too low to ensure those receiving it have “a decent living for themselves and their families,” as Qatar is required to ensure under the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR).[53] Additionally, Qatar’s current wage policy does not protect against the practice of wage discrimination by sex, race, or national origin.[54] Typically, governments and employers should account for the following costs at a minimum when determining the level of a living wage: a living wage : a basic food basket and meal preparation costs, health care, housing and energy, clothing, water and sanitation, essential transportation, children’s education, and important discretionary expenses relevant to the national context in ensuring an adequate standard of living. Qatar should also calculate and enforce an hourly minimum wage and Qatar should set up a committee that periodically reviews the minimum wage levels so that it guarantees a living wage. Moreover, the Labour Dispute Resolution Committees do not apply to workers excluded in the labor law. They are also taking longer than expected to resolve disputes and some workers still face major hurdles in reclaiming unpaid wages.[55]

The Wage “Protection” System

According to “Assessment of the Wage Protection System in Qatar”, a 2019 report authored by Dr. Ray Jureidini and issued by the International Labour Organization (ILO) Project Office for the State of Qatar, since the establishment of the WPS, 1.3 million workers and over 50,000 companies have been registered with the software.[56] However, roughly 700,000 workers remain unprotected, particularly those who work with small enterprises, and those who are deliberately excluded by the WPS such as domestic workers and agricultural workers working on small farms.[57]

Evidence laid out in the report suggests that the Wage Protection System is a misnomer for a software that, in reality, does little to protect wages, and at best, can be better described as a wage monitoring system with significant gaps in its oversight capacity.

Companies in Qatar must register with the WPS in order to pay workers electronically by the seventh day of the month; employers do this by opening an account in any of the approved banks in Qatar. [58] Every month the employer submits a document titled the Salary Information File (SIF) for each worker to the bank.[59] This file contains the worker’s identity details and how much they are owed by the company. The bank then distributes salaries into each worker’s account and is meant to notify them via SMS, at which point workers can withdraw salaries using company-issued ATM cards.

The Salary Information File is also automatically forwarded to the WPS Unit at the Ministry of Administrative Labour and Social Affairs (MADLSA, or the labor ministry), where it is the job of employees called “checkers” and “blockers” to deal with any wage abuses to which the software alerts them. The checkers and blockers decide how severe an alert is, and how the employer should be penalized, if at all. There are several reasons an alert could be issued – these include a payment of below QR50, a payment delayed by more than seven days after due date, a discrepancy between the number of employees in a company and the number of employees paid that month, unpaid overtime where overtime hours are registered but not paid, and excessive deductions of more than 50 per cent of gross salary.[60]

However, the current iteration of the WPS is riddled with loopholes that companies and employers use to exploit migrant workers. The above-mentioned ILO report states that wage-related grievances make up most of the complaints received by the Labor Relations Department, the Labour Dispute Settlement Committees, and the labor ministry. The report states that “wage abuses are still far too common” and evidence for this can be seen in the high rate of non-compliance with the Wage Protection System.[61]

The three biggest reasons that the WPS is unable to protect workers include defective formatting of the Salary Information Files, weak triggers for the alert system, and the lack of a requirement for employers to issue physical pay slips to migrant workers.

Firstly, the Salary Information File does not include the text or terms of workers’ contracts. This undermines the entire purpose of the written contract, the terms upon which migrant workers made the decision to leave their homes and families and work in Qatar. The lack of contractual details renders the WPS incapable of raising flags when employers are violating promises laid down in contracts. Moreover, Salary Information Files do not contain a separate section for overtime payments, which are instead bundled into the ‘Extra Income’ category. An ‘Unpaid Overtime’ alert is only issued when overtime hours are reported, and no payment is identified alongside. This means that an employer can escape investigation by paying a meager, inaccurate amount of overtime payment.

Secondly, the WPS only issues an alert for underpayment when the worker receives less than QR50 ($14) as their monthly wage, even though the temporary minimum wage stands at QR750 ($206) per month.[62] This limitation also allows employers to arbitrarily deduct exorbitant amounts from salaries without needing to offer an explanation.

Thirdly, neither the WPS nor employers offer physical pay slips to workers. Without pay slips that detail basic wages, food allowances, transport costs, bonuses, backpay, deductions, overtime payments, overtime hours, end of service payments and such, the employer can obfuscate the sum they owe to workers. This leaves migrant workers with little proof of how and when they were denied pay or benefits.

In addition, there is a large backlog in WPS monitoring due to understaffing. According to the ILO report “there are too few checkers to monitor the 52,000 enterprises registered (as of mid-2018), of which more than half are subject to some sort of alert that needs to be reviewed.[63] As of November 2018, the review of high-risk alerts was up to date, but checkers were still reviewing information from January 2018, mostly on smaller enterprises.”[64]

Additionally, many companies and employers have outsmarted the WPS by registering employees with inaccurate SIFs, or by completing accurate paperwork but withholding bank cards and/or ATM pins from employees.

Finally, the WPS has insufficient penalties for violations. The joint ILO and MALDSA-issued report states that the threat of fines from QR2,000 to QR6,ooo ($550 to $1,648) and jail time of no more than a month does not work as an immediate and sufficient deterrent, especially because companies are often given warnings and multiple opportunities to rectify the wage abuse after the system flags them.[65] Moreover, it is common for employers to set up a second company under another name if the first is denied government services because of WPS violations. WPS records are not always reviewed for awarding government contracts, thereby diminishing any power it could hold over companies.

Labour Dispute Resolution Committees

“I am scared that the [legal] process will cost too much, how will I feed myself and pay for transport to the labor ministry?”

–‘Alan’, a Filipino general cleaner working for a labor supply company, cites his fears of filing a wage-related dispute in the labor relations department.

In March 2018, the Labour Dispute Resolution Committees, designed to speed up the litigation process and shorten the time it takes to resolve labor disputes, assumed duties.[66] Their mandate includes hearing complaints regarding unpaid or delayed wages, breach of contract, and failure of employers to renew workers’ residence permits.

According to the 2017 law on Labour Dispute Resolution Committees, if workers have a dispute with their employer, they should first attempt to resolve it directly with their employer. If that fails, the worker can take their grievance to the Labour Relations department at the labor ministry, which is tasked with launching an attempt at mediation. If the department is unable to mediate successfully with seven days, the complaint is forwarded to the Labour Dispute Resolution Committees, which are mandated to hold the first hearing in the case within three to seven days of receiving it and to reach a decision, which is intended to have executory force, within three weeks of the first hearing.[67] Parties wishing to appeal the committee’s decision can file their appeal with an appeals court within 15 days of the decision.

In September 2019, Amnesty International released a report for which they investigated the cases of more than 2,000 workers from three companies who worked for months without salaries. At least 1,620 of these workers submitted complaints to the Labour Dispute Resolution Committees.[68] None of the workers received any compensation directly through the systems set up by the committees and a vast majority of the workers went home empty-handed. The report concludes that there are several reasons for the Committees’ ineffectiveness which include the understaffing of judges, travel costs, lack of pro bono legal services for workers, limited assistance from embassies, companies and employers’ lack of participation in legal processes, and many others.[69]

Human Rights Watch also found the process to be slow, inaccessible, and ineffective. Out of the 93 migrant workers Human Rights Watch interviewed, 15 turned to the Committees for help in receiving outstanding wages. Out of these, only one worker managed to receive part of his wages.[70] When the Labour Dispute Resolution Committee was established, it was estimated that the Committee would reach conclusions in three weeks as the law provided, and the entire process from MADLSA to executory force would take six weeks. However, Human Rights Watch found that it could take months, with the longest Human Rights Watch recorded to be eight months, which can be incredibly costly for migrant workers.[71]

‘Mary’, 28, a Filipina barista and general cleaner, has been working in Qatar since 2012 and is one of the unlucky 14 who did not receive their outstanding wages.[72] In October 2019, she said she complained to the Labour Relations department about her employer at a labor supply company withholding two months of salary (for August and September 2019), end-of-service benefits, and a ticket to the Philippines, which adds up to QR10,590 ($2,908).[73] Her employer was notified of her complaint and was asked to come in for a mediation, but responded by placing an absconding case against Mary in early December 2019.[74] Mary was arrested and spent two nights in police custody before her employer came to collect her. In January 2020, ‘Mary’ cleared her name at the Central Investigation Department (CID) in Doha by providing witnesses who corroborated that she had not run away from the accommodations. After coming out of the CID office, she told Human Rights Watch: “I have nothing left. No money. No home [her employer turned her out of the accommodations near the end of December 2019]. No job. All I have is hope that there is justice waiting for us at the Labour Dispute Resolution Committees.”[75] Her labor dispute case moved from the Labour Relations department to the Labour Dispute Resolution Committees to an appeals court, where she was given a positive verdict in February 2020. But until July 2020, Mary has not received the payments owed to her nor has she received a non-objection certificate (NOC) from her employer that would allow her to lawfully find work elsewhere.[76]

Migrant workers told Human Rights Watch they were not confident about taking concerns to the Labour Dispute Resolution Committees because they feared being deported, losing their housing, not having enough documentation to prove their case, and having employers launch false absconding cases against them. The majority of workers also expressed a lack of faith in the effectiveness and speediness of the Labour Dispute Resolution Committees and the justice system in Qatar more broadly.

For most workers that Human Rights Watch spoke to, deciding whether to pursue their right to compensation in Qatar is a Catch-22 situation: They can either wait for months and sometimes years before they finally receive some or all of their due wages through the Labour Dispute Resolution Committees process, and in doing so, they must grapple with an insecure immigration status and an inability to financially support themselves to remain in the country under the kafala system, or they can leave the country destitute and indebted without their outstanding payments. ‘Ansar’, 42, a Bangladeshi truck driver for a construction company in Qatar, told Human Rights Watch that he went to the Labour Relations department in June 2019, after his employer withheld his salary for 8 months amounting to QR14,400 ($3,955), from October 2018 to June 2019.[77] By December 2019, his case had reached the Labour Dispute Resolution Committees which had ruled in his favor. The Committee found that the employer owed Ansar eight months of wages, a ticket to Bangladesh, end-of-service benefits, and salary in lieu of vacation days he was not granted amounting to approximately QR22,710 ($6,237).[78] But as of May 2020, his company has not paid him what he is owed. “I don’t have money for food or transport. I eat only when my friends can sneak me into their company canteen, on other days, I starve. The longer I stay here to wait for my outstanding salary, the more my debt rises, but if I leave now, the nine months I have been waiting for my payments will go to waste,” he said.[79]

Human Rights Watch interviewed six other workers in Ansar’s company who had each filed cases with the Labour Relations department for non-payment of wages.[80] Ansar says a total of 35 people complained against the company and won their cases; none have received their outstanding salaries yet.[81]

‘Adan’, a 45-year-old Filipino computer technician who has been working in Doha since 2010 said his employer withheld five months’ worth of wages for the months of June to December 2019. At a monthly salary of QR2,200 ($604) this amounts to $3,020. Adan told Human Rights Watch he has no intention of seeking redress for this violation of his right to fair wages:[82]

“I could report my employer to the Labor ministry, I have all the requisite bank statements to prove they are withholding our payments, but the process takes about one year. How is one meant to survive without any pay for that year? Plus, I know people who went to the labor department and the Labour Dispute Resolution Committees, even after one year, no one was successful in getting payments from their companies.”[83]

In June 2020, MADLSA and the Supreme Judiciary Council jointly established a new office within the Labour Dispute Settlement Committees, with the purpose of implementing rulings of labor cases, and facilitate judicial transactions, quickly and without the worker having to visit another office. Whether this new office will speed the process of redress for migrant workers facing wage abuses and encourage others to come forward with complaints is yet to be seen.

Workers' Support and Insurance Fund

In 2018, the government established a fund to support workers who have suffered labor abuse and are facing financial difficulty. The Workers’ Support and Insurance Fund, according to the Government Communications Office, is intended to protect workers from the impact of overdue or unpaid wages in instances where the company fails to pay because it has gone out of business or been forced to close due to illegal activity.

According to the law mandating the fund, it would provide relief for workers who have won their cases at the Labour Dispute Resolution Committees but whose employers have failed to pay them their due compensation.[84] Instead of forcing the worker to pursue their employer further in the civil courts, the fund would provide the money owed to the worker first and then seek reimbursement from the employer, thereby shifting the burden away from the workers.

In the context of the many root problems that permit and exacerbate wage abuse in the current system, this fund could be a key measure in ensuring workers receive their dues as soon as they get a verdict from the Labour Dispute Resolution Committees instead of waiting to receive them eventually or not at all. According to Qatar's Government Communications Office in August 2020, the fund has so far benefitted 5,500 workers and disbursed 14 million Qatari Riyals ($3.85 million) in financial relief. The fund only became operational earlier this year. Key decisions on the rules and procedures for the payment of workers’ entitlement its sources of funding, the definition of workers’ entitlements, and the criteria determining the nature and extent of support, have not yet been published. Of the 15 migrant workers Human Rights Watch interviewed and who took their cases to the Labor Dispute Resolution Committees, 14 are yet to be paid their dues, through the fund or otherwise.

A June 2019 interim report published by the ILO Project Office for the State of Qatar gave 29 recommendations on how to effectively operationalize the Workers’ Support and Insurance Fund, including examples of similar funds from Singapore, Germany, Austria, Hong Kong, the UAE, Canada, China, India, Colombia, and the Dominican Republic.[85] Among its recommendations is that the fund should diversify its sources of funding (as of now 60 percent of the fund's annual budget comes from fees collected for worker's permit and their renewal), recover wages from employers, address financial pressures on the Fund, define workers’ entitlements, develop a criteria for humanitarian claims, and publish an annual report.

|

Domestic Workers More than 174,000 migrant domestic workers employed in Qatar continue to be acutely vulnerable to abuse, exploitation, and forced labor despite the passage of a law providing legal protections to domestic workers in August 2017.[86] They are excluded from labor law protections, and thus are excluded from most recently-introduced labor reforms, including the WPS and the Labour Dispute Resolution Committees. Human Rights Watch documented the gaps in the domestic workers law which are weaker than protections for workers covered in the labor law.[87] Human Rights Watch spoke to 11 domestic workers between January and December 2019, and while each domestic worker had unique issues with their employer, the most common complaints faced by each of them were underpayments, delayed payments, and non-payments. ‘Alia’, 20, a Kenyan domestic worker, said her contract stated a monthly wage of QR1,000 ($275), but each month between April and November 2019 her employer paid her only QR900 ($247).[88] ‘Maryam’, 32, a Filipina migrant worker earning QR850 ($233) per month, said for most of 2019 her employer delayed payments for up to 25 days.[89] ‘Emma’, 22, a Kenyan domestic worker earning a monthly salary of QR 900 ($247), said that between February and September 2019 her employer only paid her four out of eight salaries owed to her.[90] None of three women have access to their passports; they have not been handed their Qatari identity cards, and they do not receive pay slips that could help them prove their wage abuses to their embassies, the Qatari National Human Rights Commission, or the labor ministry. Additionally, all the domestic workers told Human Rights Watch that they worked around the clock, but do not receive overtime payments. “I wake up before my madam [employer] and sleep many hours after her. I work about 18 hours a day but am only paid for 8 hours. My body hurts so much and I am always so tense about my salary and my loans, I have forgotten what feeling relaxed means,” said Alia.[91] Like other migrant workers, domestic workers also pay huge recruitment fees to secure jobs in Qatar. Most of the workers Human Rights Watch interviewed were in debt because of these recruitment fees. In April 2020, the labor ministry urged employers to open bank accounts for domestic workers but did not make it mandatory for employers to pay domestic workers electronically. As of yet there is no information whether the WPS measures applicable to other migrant workers will eventually be applied to domestic workers as well.[92] |

Additional Measures to Tackle Wage Abuse

Other countries facing similar problems of wage abuses have adopted measures, some of which proved effective at providing workers with the full and timely wages they earned. In addition to improving the WPS and banning ‘pay when paid’ practices, Qatar could consider these measures as a means of adding additional layers of protection for workers’ wages.

In a 2018 ILO White Paper focused on the protection of construction workers in the Middle East, Jill Wells outlines six measures other countries have adopted to combat late or non-payment of wages.[93] These measures, which are summarized in the table below, are a response to the “extensive subcontracting and to the outsourcing of labor requirements to labor supply”.[94]

Below, a summary of Table 4 from the 2018 ILO White Paper titled “‘Exploratory study of good policies in the protection of construction workers in the Middle East’: Comparison of policies to protect workers against late or non-payment of wages”

|

Protects Against Insolvency |

Speeds Payments |

Measure |

|

✗ |

✗ |

1. Wage protection system (GCC) An electronic salary transfer system designed to pay wages directly into the accounts of workers. This promotes worker welfare, gives workers proof of non-payment through bank statements, and limits workers’ incentives to strike. This measure has limited coverage. |

|

✗ |

✓ |

2. Prompt Payment Legislation (EU Directive) Designed to tighten EU regulation on late payments owed by public or private debtors. Public debtors process their accounts within 30 days from the date of the invoice, and penalties include a high interest rate. This improves knowledge of the adverse impact of late payments. Creditors are reluctant to use this measure for fear of jeopardizing client relationships. |

|

✗ |

✓ |

3. Ban ‘pay when paid’ (Construction Acts in the UK and Ireland) Governments are encouraged to introduce legislation banning ‘pay when paid’ clauses in all contracts and include the right of contractors and subcontractors to suspend performance for non-payment. This protects subcontractors against late payments by clients, but firms are reluctant to use this measure for fear of jeopardizing client relationships. |

|

✗ |

✓ |

4. Introduce rapid adjudication (Construction Acts in UK & Ireland) This process ensures the payment of undisputed items while disputed items are being discussed and agreed upon. Setting up this method requires resources, but it gives certainty of date of payments to contractors and subcontractors. |

|

✓ |

✓ |

5a. Project Bank Account (UK) A ring-fenced account is set up at the start of a project as the medium through which payments are made. The client pays funds into the account each time that payment is due. This system ensures subcontractors’ payments but the system takes time to be set up. |

|

✓ |

✓ |

5b. Subcontract payment monitoring system (Seoul) In this all project funds are paid through a special project bank account which is ringfenced and set up by the general contractor. It needs the cooperation of banks and a ‘Software Payment Verification System’. It allows direct payment from a protected account for the whole chain, but it needs enforcement by client ordinance and penalties for noncompliance. |

|

✓ |

✓ |

6. Joint liability - Direct payment from client to subcontractor (EU) Making clients and principal contractors jointly liable for ensuring that subcontractors and workers receive payments. It legitimizes direct payment across links in the subcontracting chain, from client to subcontractors or principal contractor to workers. This protects workers’ rights to fair wages in subcontracting processes and is most common in public works. |

II. Employers’ Salary Abuses Against Migrant Workers

The Qatari government marketed the Wage Protection System (WPS), the Labour Dispute Resolution Committees, and the Workers’ Support and Insurance Fund as solutions to one of the most burning issues plaguing migrant workers in Qatar: salary abuses. But five years after the launch of the WPS and three years since the committees and the fund were established, every worker Human Rights Watch spoke to reported suffering at least one, and often several, forms of wage abuse at the hands of their employers. These abuses included delayed or unpaid wages, withholding of wages, underpaid wages, lack of overtime wages, contract substitution, and employers’ withholding contractually obligated departure payments.

Of the 93 migrant workers Human Rights Watch interviewed from 60 companies and employers, 59 workers reported unpaid wages or serious delays in receiving their wages. Thirty-five workers said that their employers did not honor the wage amount stipulated in their contract. Even in cases where contracts were approved by the government and the employee is receiving payments through a bank account monitored by the WPS, employers found ways to violate the contract’s terms regarding basic wages without any accountability. Fifty-five workers cited lack of overtime payments as a major issue they faced. Not only were their overtime hours worked recorded inaccurately, but in the majority of cases employers completely disregarded their overtime hours—although they worked up to 18-hour days, their employers only compensated them for 8 hours of a regular day’s work. Thirteen workers reported facing contract substitution, and 20 workers said that their employers do not pay the required departure payments, which include end-of-service benefits, tickets to home countries, and any previously-withheld or otherwise outstanding wages.

Delayed and Unpaid Wages

“They cheat us with fake promises of paying us ‘soon.’ They play with our lives and our children’s lives.”

- ‘Avinash’, 33-year-old Indian engineer at a construction company in Qatar[95]

The most egregious forms of wage abuse migrant workers say they experience in Qatar are delayed and unpaid salaries. Human Rights Watch spoke to 59 migrant workers who said their salaries were delayed or unpaid. In some cases, delayed salaries meant that instead of getting paid every month as Qatari law states, workers are paid once every two or three months. In other cases, employers delayed workers’ salaries for as long as six months, often leaving workers in dire circumstances including incurring debts along the way.

‘Gopal’, 34, a Nepali site engineer, came to Qatar in 2015. In 2018 he began working at a fire station in the far western area of Qatar. Gopal told Human Rights Watch that his salary of QR1,800 (US$494) per month was paid on time until February 2019 when it stopped coming altogether. In August 2019, after receiving no salary or food allowance for 7 months, Gopal went to the Labor department to begin the proceedings to receive QR12,600 ($3,460) of unpaid wages.[96] He told Human Rights Watch he is on the brink of “starving” due to his employer’s wage abuses. In December 2019 he told Human Rights Watch:

Recently my family in Nepal wanted to celebrate Diwali [a Hindu festival], my daughters wanted new clothes and bangles. I borrowed from friends to send money to them. I am so worried about all the loans I have taken this year, how will I pay them back if I don’t get my salary? Sometimes I think suicide is my only option.[97]

As of May 2020, Gopal’s case had reached the Labour Dispute Resolution Committee and he was still waiting in Qatar for his money.[98]

‘Tamang’, a 24-year-old Nepali delivery man told Human Rights Watch that his monthly salary of QR750 ($206) was delayed for more than two months between December 2019 and February 2020. Tamang said his employer paid his and 52 other workers’ two salaries in the middle of February 2020. By then, they were already in debt. “We were buying groceries on credit for two months and now that we have been paid, we have repaid our previous loans but have no money left over for food for this month,” said Tamang.[99]

Human Rights Watch interviews with migrant workers found that most abuses regarding delayed or non-payment of salaries are companywide. In other words, when one worker is facing delays, often a sizable number of the company’s other employees are as well.

A trading and construction company apparently delayed five months of salaries for roughly 500 managerial staffers and two months of salaries for approximately 500 laborers between September 2019 and February 2020. This company has over 25 current projects in Qatar, some of which include a stadium which will host FIFA World Cup 2022 matches, the streets surrounding the stadium, and a road-building project. Staffers at this company reported that this was not the only time salaries had been delayed.[100]

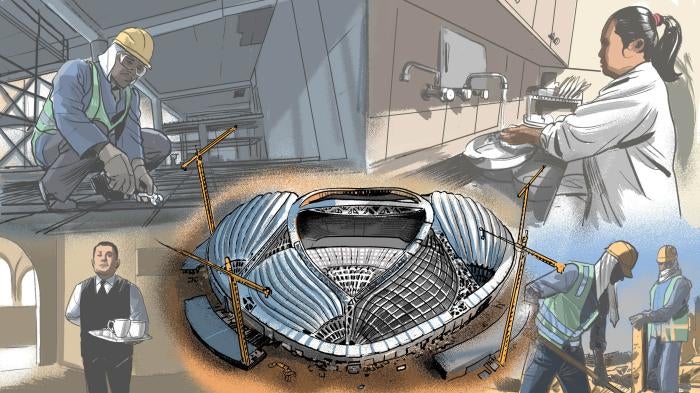

The management staff said they reported to work without pay under threat of deductions until several staff members decided to stop working until they were paid. Staffers told Human Rights Watch that the employer and their top-level management also made similar threats to keep laborers working throughout December 2019 and January 2020. On February 9, the employees risked arrest and publicly protested against delayed wages.[101] The senior management of the company intervened at the protest and told employees that the government has promised to pay all outstanding salaries.[102] Within a week, all the employees had been paid their outstanding salaries.

In addition, unpaid or delayed wages affect workers’ ability to repay loans and they can find themselves under travel bans or even prison for defaulting. One engineer at the above-mentioned company told Human Rights Watch that after his salary was delayed in September 2019, he took a loan of QR15,000 ($4,119) from the bank in October 2019. By the time he received his delayed salaries in February 2020 he had already defaulted on his loan and his bank told him he had been placed under a travel ban and a police case had been launched against him for defaulting on his loan.[103] Eventually, he was able to pay back the loan and clear his name from the police case, but he told Human Rights Watch he missed his wife giving birth to their child in India due to the salary delays and the consequent travel ban.[104]

Employers Withholding Wages to Migrant Workers

Human Rights Watch spoke to seven workers who reported that their employers deliberately withheld their wages as “security deposits.”[105] This practice falls directly under the ILO’s indicators of forced labor, which the ILO’s Forced Labour Convention describes as “all work or service which is exacted from any person under the menace of any penalty and for which the said person has not offered himself voluntarily.”[106]

‘Kapil’, a 27-year-old worker from India, is an engineer in Qatar. The company he worked for in Qatar shut down in June 2018, and he said he felt lucky when he was one of the few transferred to a sister company. But after his first month at the new company, Kapil did not feel as fortunate. “The first month my monthly salary of QR2,500 ($686) was withheld. They do this to everyone who joins the company. They feel it keeps workers from running away, like a security deposit.[107] In my opinion it is a form of blackmail,” said Kapil. “I know the company was not short on cash because for the next seven months they paid us on time.” Kapil also explained that withholding wages has an adverse psychological impact on workers. “When we know they have our salary, we are more scared to ask for our rights. This is how they control us,” said Kapil.[108]

Another worker who earns a monthly salary of QR800 ($219), ‘Suleiman’, 29, who came from India in 2017 to work in Qatar told Human Rights Watch that all the laborers in the construction company he works for are not paid the first month’s salary.[109] “I arrived in January 2018, but I received my first salary in March. That salary was for the work I did in February. They said my January salary was a security deposit that will be paid when I leave,” said Suleiman. “By the time people leave, there are so many other missing salaries and overtime payment discrepancies that this first month’s salary is lost.”

Human Rights Watch also documented instances of labor supply companies withholding wages. ‘Rachel’, 30, a Filipino migrant worker, employed by a labor supply company in Doha since 2017, worked as a cleaner in Doha for QR 1,500 ($411) per month.[110] Rachel’s employer rarely paid her on time. In September 2019, as Rachel’s two-year contract with the company was ending, the labor supply company stopped paying altogether. “They said either I keep working with them for my remaining three years, or I can leave without two months of outstanding payments amounting to $822,” said Rachel, detailing how her employer withheld her wages as a form of blackmail.[111]

|