Summary

If we don’t get education, our nation won’t progress.

—Rabiya, 23, single mother of a daughter, Karachi, July 2017.

Pakistan was described as “among the world’s worst performing countries in education,” at the 2015 Oslo Summit on Education and Development. The new government, elected in July 2018, stated in their manifesto that nearly 22.5 million children are out of school. Girls are particularly affected. Thirty-two percent of primary school age girls are out of school in Pakistan, compared to 21 percent of boys. By grade six, 59 percent of girls are out of school, versus 49 percent of boys. Only 13 percent of girls are still in school by ninth grade. Both boys and girls are missing out on education in unacceptable numbers, but girls are worst affected.

Political instability, disproportionate influence on governance by security forces, repression of civil society and the media, violent insurgency, and escalating ethnic and religious tensions all poison Pakistan’s current social landscape. These forces distract from the government’s obligation to deliver essential services like education—and girls lose out the most.

There are high numbers of out-of-school children, and significant gender disparities in education, across the entire country, but some areas are much worse than others. In Balochistan, the province with the lowest percentage of educated women, as of 2014-15, 81 percent of women had not completed primary school, compared to 52 percent of men. Seventy-five percent of women had never attended school at all, compared to 40 percent of men. According to this data, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa had higher rates of education but similarly huge gender disparities. Sindh and Punjab had higher rates of education and somewhat lower gender disparities, but the gender disparities were still 14 to 21 percent.

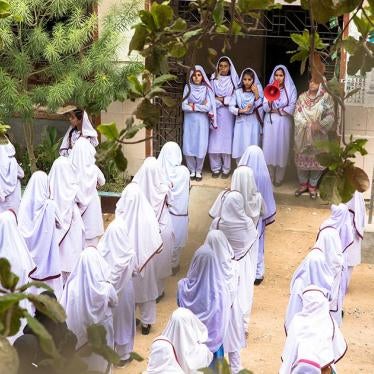

Across all provinces generation after generation of children, especially girls, are locked out of education—and into poverty. In interviews for this report, girls talked again and again about their desire for education, their wish to “be someone,” and how these dreams had been crushed by being unable to study.

Lack of access to education for girls is part of a broader landscape of gender inequality in Pakistan. The country has one of Asia’s highest rates of maternal mortality. Violence against women and girls—including rape, so-called “honor” killings and violence, acid attacks, domestic violence, forced marriage and child marriage—is a serious problem, and government responses are inadequate. Pakistani activists estimate that there are about 1,000 honor killings every year. Twenty-one percent of females marry as children.

Pakistan’s education system has changed significantly in recent years, responding to an abdication by the government of responsibility to provide, through government schools, an adequate standard of education, compulsory and free of charge, to all children. There has been an explosion of new private schools, largely unregulated, of wildly varying quality. A lack of access to government schools for many poor people has created a booming market for low-cost private schools, which in many areas are the only form of education available to poor families. While attempting to fill a critical gap, these schools may be compromised by poorly qualified and badly paid teachers, idiosyncratic curricula, and a lack of government quality assurance and oversight.

Secondly, there has been a massive increase in the provision of religious education, ranging from formal madrasas to informal arrangements where children study the Quran in the house of a neighbor. Religious schools are often the only type of education available to poor families. They are not, however, an adequate replacement, as they generally do not teach non-religious subjects.

Pakistan’s highly decentralized structure of government means that many decisions regarding education policy are made at the subnational level. The result is a separate planning process in every province, on a different timeline, with varying approaches, levels of effectiveness and commitment to improving access to education for girls. This leads to major differences from one province to the next, including on such basic issues as whether children are charged fees to attend government schools, and how much teachers are paid.

In every province, however, there is a serious gender disparity, a high percentage of both boys and girls who are out of school, and clear flaws in the government’s approach to education.

Barriers to Girls’ Education Within the School System

Many of the barriers to girls’ education are within the school system itself. The Pakistan government simply has not established an education system adequate to meet the needs of the country’s children, especially girls. While handing off responsibility to private school operators and religious schools might seem like a solution, nothing can absolve the state of its obligation, under international and domestic law, to ensure that all children receive a decent education—something that simply is not happening in Pakistan today. Moreover, despite all the barriers, many people interviewed for this report described a growing demand for girls’ education, including in marginalized communities.

Lack of Investment

The government does not adequately invest in schools. Pakistan spends far less on education than is recommended by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in its guidance on education. Many professionals working in the education sector described a situation in which the government seemed disinterested, and government disengagement on education is evident from the national level to the provincial and local levels.

One result is that there are not enough government schools for all children to have access to one. Government schools are in such short supply that even in Pakistan’s major cities many children cannot reach a school on foot safely and in a reasonable amount of time. The situation is far worse in rural areas, where schools are even more scarce, and it is less likely that private schools will fill the gap. Families that can access a government school often find that it is overcrowded.

An “upward bottleneck” exists as children, especially girls, get older. Secondary schools are in shorter supply than primary schools, and colleges are even more scarce, especially for girls. Schools are more likely to be gender segregated as children get older, and there are fewer schools for girls than for boys. Many girls are pushed out of continuing studies because they finish at one school and cannot access the next grade level.

High Cost of Education

Poor families struggle to meet the costs of sending their children to school. Government schools are generally more affordable than private education, but they sometimes charge tuition, registration or exam fees, and they almost always require that students’ families foot the bill for associated costs. These include stationery, copies, uniforms, school bags, and shoes. Text books are sometimes provided for free at government schools, but sometimes families must pay for these as well.

The many poor families who cannot access a government school are left with options outside the government school system. The range of private schools, informal tuition centers, nongovernmental organization (NGO) schools, and madrasas creates a complex maze for parents and children to navigate. Many girls experience several—or all—of these forms of study without gaining any educational qualifications.

Poor Quality of Education

Many families expressed frustration about the quality of education available to them. Some said it was so poor that there was no point sending children to school. In government schools, parents and students complained of teachers not showing up, overcrowding, and poor facilities. At private schools, particularly low-cost private schools, concerns related to teachers being badly educated and unqualified, and the instruction being patchy and unregulated. Teachers in both government and private schools pressure parents to pay for out-of-school tutoring, an additional expense. In both government and private schools, use of corporal punishment and abusive behavior by teachers was widely reported.

No Enforcement of Compulsory Education

One reason so many children in Pakistan do not go to school is that there is no enforced government expectation that children should study. Pakistan’s constitution states, “The State shall provide free and compulsory education to all children of the age of five to sixteen years in such manner as may be determined by law.” However, there is no organized effort by government in any province to ensure that all children study. When children are not sent to school, no government official reaches out to the family to encourage or require that the child study. When a child drops out of school, individual teachers sometimes encourage the child to continue studying, but there is no systematic government effort to enroll or retain children in school. This violates international standards Pakistan has signed up to which require that education be free and compulsory at least through primary school.

Corruption

Corruption is a major issue in the government school system and exists in several forms. One of the most pervasive is nepotism or bribery in the recruitment of teachers and principals. Some people simply purchase teaching positions, and others obtain their jobs through political connections. When people obtain teaching positions illicitly, they may not be qualified or motivated to teach, and they may not be expected to. Especially in rural areas, some schools sit empty because corruption has redirected the teacher’s salary to someone who does not teach, according to education experts.

Barriers to Girls’ Education Outside the School System

Aside from the barriers to education within the school system, girls also face barriers in their homes and in the community. These include poverty, child labor, gender discrimination and harmful social norms, and insecurity and dangers on the way to school.

Poverty

For many parents, the most fundamental barrier to sending their children to school is poverty. Even relatively low associated costs can put education out of reach for poor families, and there are many poor families in Pakistan. In 2016, the government determined that about 60 million Pakistanis—6.8 to 7.6 million families—were living in poverty, about 29.5 percent of the country’s population.

Many children, including girls, are out of school because they are working. Sometimes they are engaged in paid work, which for girls often consists of home-based industries, such as sewing, embroidery, beading, or assembling items. Other children—almost always girls—are kept home to do housework in the family home or are employed as domestic workers.

Social Norms

Some families do not believe that girls should be educated or believe girls should not study beyond a certain age. Attitudes regarding girls’ education vary significantly across different communities. In some areas, families violating cultural norms prohibiting girls from studying can face pressure and hostility. When families violate norms against girls’ education, the girls themselves may face harmful consequences. Many people, however, described growing acceptance of the value of girls’ education, even in conservative communities; the government should be encouraging this change.

Girls are often removed from school as they approach puberty, sometimes because families fear them engaging in romantic relationships. Other families fear older girls will face sexual harassment at school and on the way there and back.

Harmful gender norms create economic incentives to prioritize boys’ education. Daughters normally go to live with, and contribute to, their husband’s family, while sons are expected to remain with their parents—so sending sons to school is seen as a better investment in the family’s economic future.

Child marriage is both a consequence and a cause of girls not attending school. In Pakistan, 21 percent of girls marry before age 18, and 3 percent marry before age 15. Girls are sometimes seen as ready for marriage as soon as they reach puberty, and in some communities, child marriage is expected. Some families are driven to marry off their daughters by poverty, and others see child marriage as a way of preempting any risk of girls engaging in romantic relationships outside marriage. Staying in school helps girls delay marriage, and girls often are forced to leave school as soon as they marry or even become engaged.

Insecurity

Many families and girls cited security as a barrier to girls studying. They described many types of insecurity, including sexual harassment, kidnapping, crime, conflict, and attacks on education. Some families said insecurity in their communities worsened in recent years, meaning younger children have less access to education than older siblings.

Families worry about busy roads; the large distance many girls must travel to school increases risks and fears. Many girls experienced sexual harassment on the way to school, and police demonstrate little willingness to help prevent harassment. Girls sometimes hesitate to complain about harassment out of fear they will be blamed, or their parents’ solution will be to take them out of school.

Girls and families also fear kidnapping, another fear exacerbated by long journeys to school. This fear is heightened when girls are older and seen as being at greater risk of sexual assault. Attacks on education are disturbingly common in Pakistan. When violence happens in a school or in a neighborhood, it has long term consequences for girls’ education. Families across different parts of the country described incidents of violence in their communities that kept girls out of school for many years afterwards.

Armed Conflict and Targeted Attacks on Schools

Many parts of Pakistan face escalating levels of violence related to insurgency, and ethnic and religious conflict. This is having a devastating impact on girls’ access to education, and ethnic conflict often spills into schools.

One of the features of conflict in Pakistan has been targeted attacks against students, teachers, and schools. The most devastating attack on education in recent years in Pakistan was the December 2014 attack on the Army Public School in Peshawar city, where militants killed 145 people, almost all of them children. This attack was far from isolated, however. Between 2013 and 2017, hundreds of schools were attacked, typically with explosive devices, killing several hundred students and teachers, and damaging and destroying infrastructure. One-third of these attacks specifically targeted girls and women, aiming to interrupt their studies.

Pakistan can, and should, fix its school system. The government should invest more resources in education and use those resources to address gender disparities and to ensure that all children—boys and girls—have access to, and attend, high quality primary and secondary education. The future of the country depends on it.

Key Recommendations

To the Federal Government of Pakistan

- Increase expenditure on education in line with UNESCO recommended levels needed to fulfill obligations related to the right to education.

- Strengthen oversight of provincial education systems’ progress toward achieving parity between girls and boys and universal primary and secondary education for all children, by requiring provinces provide accurate data on girls’ education, monitoring enrolment and attendance by girls, and setting targets in each province.

- Strengthen the federal government’s role in assisting provincial governments in provision of education, with the goal of ending gender disparities in all provinces.

- Work with provincial governments to improve the quality of government schools and quality assurance of private schools.

- Raise the national minimum age of marriage to 18 with no exceptions and develop and implement a national action plan to end child marriage, with the goal of ending all child marriage by 2030, as per Sustainable Development Goal target 5.3.

- Endorse and implement the Safe Schools Declaration, an international political agreement to protect schools, teachers, and students during armed conflict.

To Provincial Governments

- Direct the provincial education authority to make girls’ education a priority within the education budget, in regard to construction and rehabilitation of schools, training and recruitment of female teachers, and provision of supplies, to address the imbalance between the participation of girls and boys in education.

- Strengthen enforcement of anti-child labour laws.

- Instruct police officials to work with schools to ensure the safety of students, including monitoring potential threats to students, teachers and schools, and working to prevent harassment of students, especially girls.

- Ensure that anyone encountering corruption by government education officials has access to effective and responsive complaint mechanisms.

To Provincial Education Authorities

- Rehabilitate, build, and establish new schools, especially co-ed and girls’ schools.

- Until government schools are available, provide scholarships to good-quality private schools for girls living far from government schools.

- Provide free or affordable transport for students who travel long distances or through difficult environments to get to a government school.

- Abolish all tuition, registration, and exam fees at government schools.

- Provide poor students with all needed items including school supplies, uniforms, bags, shoes, and textbooks.

- Instruct all principals to identify out-of-school children in their catchment areas and work with families to get them into school.

- Explore options for increasing attendance by girls from poor families through scholarships, food distribution, or meal programs at girls’ schools.

- When children quit school or fail to attend, ensure all schools reach out to determine the reasons and re-engage the student in school.

- Require each school to develop and implement a security plan with attention to concerns of girls including sexual harassment.

- Develop a plan to expand access to middle and high school for girls through the government education system, including establishment of new schools.

- Strengthen the system for monitoring and quality assurance of all schools, not only for government schools but also private schools and madrasas.

- Prohibit all forms of corporal punishment in schools; take appropriate disciplinary action against any employee violating this rule.

- Ensure that all schools have adequate boundary walls, safe and private toilets with hygiene facilities, and access to safe drinking water.

Methodology

This report is primarily based on research conducted in Pakistan in 2017 and 2018. Human Rights Watch researchers carried out a total of 209 individual and group interviews, mainly in Karachi, Lahore, Peshawar, and Quetta.

Most of the interviewees—a total of 119—were girls and young women who either had missed all of their primary and secondary education or had started some education but were unable to continue and dropped out. We also interviewed 60 parents and other family members of children who either had not attended school or had dropped out.

In addition, we interviewed 12 teachers, and four school principals. An additional 18 interviews were with education experts, activists and community workers, or local officials.

Interviews with children and families were usually conducted in their homes, or at the home of a neighbor. Some interviews were conducted in the offices of community-based organizations or at schools. Whenever possible, interviews were conducted privately with only the interviewee, a Human Rights Watch researcher, and, where necessary, an interpreter present. Interviews were conducted in Urdu, Punjabi, Pashto, Sindhi, Saraiki, Brahui, and, with some experts and educators, in English. In a few cases, interviews were conducted through double translation. Some interviews with experts were conducted by phone or in person outside of Pakistan.

All interviewees were advised of the purpose of the research and how the information would be used. We explained the voluntary nature of the interview and that they could refuse to be interviewed, refuse to answer any question, and terminate the interview at any point. Interviewees did not receive any compensation. The names of children and family members have been changed to pseudonyms to protect their privacy. The names of other interviewees have sometimes been withheld at their request.

We selected research sites in Karachi, Lahore, Peshawar, and Quetta with the goal of getting a sample of different experiences of out-of-school children and their families, including in urban environments. We made an effort to include families who migrated to the city from rural areas, and refugee families. We also conducted interviews in some rural areas, but the research was primarily in urban areas. Security challenges affected our choice of research sites.

In this report, the terms “child” and “children” are used to refer to anyone under the age of 18, consistent with usage under international law.

At the time of the research for this report, the exchange rate was approximately 105 Pakistani rupees=US$1. We have used this rate for conversions in the text.

I. Background

Pakistan was described as “among the world’s worst performing countries in education,” at the 2015 Oslo Summit on Education and Development.[1] The new government, elected in July 2018, stated in their manifesto that nearly 22.5 million children are out of school.[2] Thirty-two percent of primary school age girls are out of school in Pakistan, versus 21 percent of boys in that age group.[3] This represents a total of almost 5 million children of primary school age who are not in school, 62 percent of them girls.[4]

As children reach middle school level—sixth grade, when children would typically be about age 10 or 11—the total number of out of school children increases, and the gender disparity persists. In 2016, 59 percent of middle school girls were out of school versus 49 percent of boys.[5] According to 2013-2014 data, by ninth grade, only 13 percent of girls are still in school.[6]

Both boys and girls are missing out on education in unacceptable numbers, but girls are worst affected, especially poor girls. Among the poorest students, only 30 percent of boys finish primary school, and only 16 percent of girls.[7] By lower secondary school, the numbers of the poorest children completing their studies is even more unequal: 18 percent of boys and 5 percent of girls.[8] Only one percent of the poorest girls finish upper secondary school, compared with 6 percent of the poorest boys.[9]

Political instability, disproportionate influence on governance by security forces, repression of civil society and the media, violent insurgency, and escalating ethnic and religious tensions all poison Pakistan’s current social landscape. These forces distract from the government’s obligation to deliver essential services like education—and girls lose out the most.[10]

There are high numbers of out-of-school children, and significant gender disparities in education, across the entire country, but some areas are much worse than others. As of 2014-2015, which is the most recent published data, the percentage of people who had ever attended school was:

Balochistan: 25 percent of women, 60 percent of men

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa: 36 percent of women, 74 percent of men

Sindh: 50 percent of women, 71 percent of men

Punjab: 56 percent of women, 74 percent of men

Similar gender and regional disparities existed among those who completed primary school:

Balochistan: 19 percent of women, 48 percent of men

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa: 28 percent of women, 59 percent of men

Sindh: 43 percent of women; 62 percent of men

Punjab: 47 percent of women; 61 percent of men[11]

Across all provinces, generation after generation of children, especially girls, are locked out of education—and into poverty. In interviews for this report, girls talked again and again about their desire for education, their wish to “be someone,” and the ways in which these dreams had been crushed by being unable to study.

Lack of access to education for girls is part of a broader landscape of gender inequality in Pakistan. The country has one of Asia’s highest rates of maternal mortality.[12] Violence against women and girls—including rape, so-called “honor” killings and violence, acid attacks, domestic violence, forced marriage and child marriage—is a serious problem, and government responses are inadequate.[13] Pakistani activists estimate that there are about 1,000 honor killings every year.

One particularly concerning theme in some interviews for this report was numerous families in which children were less educated than their parents, or younger siblings were less educated than older siblings. Some families were unrooted by poverty or insecurity in ways that blocked children from studying. Some encountered financial difficulties that made it impossible for children to reach the educational level their parents had achieved. In some communities, schools had closed, or the route to school had become more unsafe. In a few families, views hostile to girls’ education had hardened over time.[14]

Pakistan’s education system has changed significantly in recent years, responding to an abdication by the government of responsibility to provide, through government schools, an adequate standard of education, compulsory and free of charge, to all children. There has been an explosion of new private schools, largely unregulated, of wildly varying quality. The number of private schools increased by 69 percent during the period from 1999-2000 to 2007-2008 alone, a period during which the number of government schools increased by only 8 percent.[15] This increased the private schools’ share of total student enrollment to 34 percent.[16] The All Pakistan Private Schools Federation has 197,000 member schools.[17]

There has also been a massive increase in the number of programs offering religious education, ranging from formal madrasas to informal arrangements where children study the Quran in the house of a neighbor. Because many religious schools are informal, it is difficult to estimate how many exist, but commentators agree that the number has risen sharply over recent decades.[18]

A variety of nonprofit schools also exist in Pakistan, though there are far too few to meet the needs of the many families struggling to access education. They range from tiny informal arrangements, such as individuals tutoring a few children in their home for free, to “informal schools” some of which are funded by international donors, to organizations like the Citizens Foundation which boasts over 200,000 students.[19] The Citizens Foundation charges low fees—175 rupees per month (US$1.67).[20]

Some nonprofit private schools are only for girls.[21] Others are based in particularly marginalized communities including, for example, schools located in areas with many Afghan immigrants or in fishing communities.[22]

The lines between nonprofit schools and private tuition can be blurred, with some informal schools representing a mix of philanthropy and business, with some teachers charging students who can pay and letting the poorest children attend for free.[23] Tuition teachers sometimes aim to transition their students into a government school but face the same barriers—usually distance and cost—that kept the students out of school in the first place.[24]

In addition to schools run as charities, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) also sometimes help other schools, for example by providing books to schools in poor areas.[25] The demand for assistance is far greater than the supply. Many families said they had sought assistance from charities to educate their children but were unable to find help.[26]

Research on educational outcomes for different types of educational institutions suggests that when you control for the differences in intake characteristics of students between government and private schools, their outcomes are in terms of testing achievement are similar.[27] On the other hand, outcomes for children who studied only at madrasas were considerably worse.[28]

Pakistan’s highly decentralized structure of government means that decisions regarding education policy are mostly made at the subnational level, consisting of four provinces (Balochistan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Punjab, and Sindh), the capital area containing Islamabad, and the federally-administered tribal areas near the Afghanistan border, and the administrative entities of Azad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan. Every province has a separate planning process, on a different timeline, with varying approaches and levels of effectiveness and commitment to improving access to education for girls.[29] The result is that education policies and practices vary significantly from one part of the country to the next, including on such basic issues as whether children are charged fees to attend government schools, and how much teachers are paid.

Despite all the barriers, many people interviewed for this report described a growing demand for girls’ education, including in marginalized communities. Aziza, 45, lives in a fishing community on the fringes of Karachi. She never studied; all her five children attended at least a few years of school, though none went beyond primary education. “Now it reflects well on the parent when a child is able to do well for themselves,” Aziza said. “Back then in this area we had no experience of educated people, but now we do. So, everyone is interested now in getting an education.”[30]

Some experts pointed to growing acceptance that girls should study. A school headmaster cited four reasons for this: 1) a desire by boys and men to marry educated brides; 2) growing availability of education as a result of the spread of private schools; 3) efforts by the government to push people away from studying in madrasas and toward mainstream education; and 4) a growing belief by families that educated women better contribute to their families, even if their role is only inside the home.[31]

Alima is sending her 20-year-old daughter to college, where she is in 11th grade, even though the family struggles to survive on the money Alima earns as a seamstress and her husband as a fruit seller. [32] Alima’s two older children, both sons, left school in ninth and 10th grades to work as weavers to help meet the family’s rent. “Because she’s the last child we put in all this effort for her,” Alima said. “If it was up to me, I would put the same kind of focus on all my children, but because of our financial situation I couldn’t. Now, because there are four people in the family earning, we can.… I hope she can study to the point where she doesn’t have to live like me.”[33]

“A lot of work is behind this awareness,” an NGO worker in a poor area of Karachi said, describing what she said was swiftly growing demand for education in the area. She attributed the change to the work of NGOs and others in creating schools in the area. “The literacy rate here is quite high compared to some other areas,” she said. “There are a lot of schools here and people are generally aware regarding the importance of education.”[34]

“Some people say girls should take care of homes, they shouldn’t study,” said a school headmaster in Punjab. “Since they are children, they are preparing to be housewives. But very few people think like this now.”[35]

“I’ve never even seen the face of a school,” said Razia, 37, a mother of four. “I really wanted to study, but my father wouldn’t let me.… In our family it is a tradition that girls don’t study.” Razia struggled to teach herself to read, and she says girls’ education is more accepted now, including in her own family. “The girls in my family are all studying now,” she said. “Things have changed because education changes you…. Before people weren’t educated and now they are and that’s made them accept girls.”[36]

II. Barriers to Girls’ Education within the School System

[E]very mother wants their child to be educated but there is not a state system to deliver the services.

—Head of a community-based organization, Karachi, July 2017

While girls face barriers to education outside the school system, many of the most serious barriers to girls’ education are within the school system. The government’s education system suffers from a chronic lack of investment. This means that many children are too far from the nearest school to travel there safely in a reasonable amount of time, if they do not have access to transportation, a problem that becomes more acute as children reach higher grades and schools are in ever-shorter supply. Compulsory education exists on paper but there is no functioning mechanism to require that children go to school. Corruption and nepotism affect who gains employment in the school system, and rural areas are particularly underserved. The Pakistan government has not established an education system adequate to meet the needs of the country’s children.

Lack of Investment

The government does not adequately invest in schools. A 2015 paper commissioned by the United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) found that to meet the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals education targets, which include universal completion of primary and secondary school, Pakistan would need to at least double the percentage of GDP going to education.[37]

According to UNESCO guidance to governments, in order for the government to fulfill its obligations on education, it should spend at least 15 to 20 percent of the total national budget, and 4 to 6 percent of GDP, on education.[38] Pakistan is one of about 33 countries which meets neither of these benchmarks, and the percentage increase in expenditure on education has sometimes lagged behind the rate of economic growth, reducing the percentage of GDP spent on education.[39]

As of 2016, 12.6 percent of Pakistan’s total expenditure went to education, and as of 2017, 2.758 percent of Pakistan’s GDP was spent on education—both figures well below recommended benchmarks.[40] This low investment continues in spite of a government commitment in 2009 to spend 7 percent of GDP on education, and makes Pakistan the only country in Asia to spend more on its military than on education.[41]

In its 2017-2025 National Education Policy, the government is blunt about its own neglect of the education system, writing:

Pakistan’s education sector has persistently suffered from under-investment by the state, irrespective of the governments in power. Years of lack of attention to the education sector in the form of inadequate financing, poor governance as well as lack of capacity, has translated into insufficient number of schools, low enrolment, poor facilities in schools, high dropout rate, shortage and incompetent teachers, etc. All of this has led to poor quality of education for those who are fortunate enough to get enrolled and no education for the rest.[42]

This diagnosis is refreshingly honest. But there are few signs that it is triggering solutions. Professionals working in the education sector described a situation in which the government seemed disinterested, sometimes pointing out that policymakers send their children to high quality and expensive private schools, and lack any personal investment in the quality of government education.[43] “The state has never taken education seriously—proper resources have never been allocated in any state,” the head of an NGO in Punjab told Human Rights Watch. “The problem is the priories of government—education is not a priority and they don’t allocate the budget.”[44]

Several experts pointed to the government failing to spend even the inadequate amount allocated to education, including funding from the government budget and from international donors, saying underspending occurs consistently and across regions.[45] “Money is going to waste. There’s no system. You need a system of checks and balances and monitoring and political will. You have to have the will,” an expert in Sindh said.[46]

Lack of Enforcement of Compulsory Education

If parents won’t allow their girls to go to school, what can the government do?

—Zarafshan, 18, forced out of school by her uncle at age 12, Karachi, July 30, 2017.

Pakistan’s constitution states, “The State shall provide free and compulsory education to all children of the age of five to sixteen years in such manner as may be determined by law.”[47] Under Pakistan’s decentralized system of service delivery, responsibility rests with provincial governments to pass and enforce laws making education compulsory. In reality, however, there is no organized effort by government to ensure that all children study.

When children are not enrolled in school, no government official reaches out to the family to encourage or require that the child study. When a child drops out of a government school, individual teachers may encourage the child to continue studying, but there is no systematic government effort to enroll or retain children in school. This is incompatible with the constitution and international standards Pakistan has signed up to which require that education be free and compulsory at least through primary school.

Some children try to enforce their right to education through their parents. “My younger daughters go up to their father and say, ‘Put us in school or the government will throw you in jail,’” Zunaisha, 35, said, laughing. “But their father says he can’t afford it.” Zunaisha’s oldest daughter, Hafsa, 16, interjected: “He won’t allow it.” Hafsa was forced to leave school after a year, something she deeply regrets, saying she now has no dreams. “You can only have interests and hobbies if you have an education.” She tried to convince her parents to let her four younger sisters, ages seven to 15, study, but without success. “It’s my father and brothers who don’t let me go to school,” she said. “I think it should be mandatory for girls to study until the 1oth grade. Then if they want to, they can study further.”[48]

Outreach by the government to encourage families to access education—and explain that education is compulsory—could make an immediate difference. Safina, 40, never went to school. She is a mother of 10 children, ages six to 22. One of her children is studying, but she said her other children refused to go and said they were not interested. “The government should have meetings with the parents and explain that kids should go to school,” she said. She suggested the government should send people house to house to talk about education. “Nobody came,” she said. “I wish the same things everyone wishes—that my kids go on to study.”[49]

In the absence of compulsory education, children sometimes decide themselves whether to study. “My father tried to make me go [to school]—he had no good job but still he wanted his kids to go,” said Kaarima, 19. Her father washes cars for a living. She left school at age 10, after fourth grade, because, she said, she was “not interested.” Some of Kaarima’s siblings study, and some do not.[50] Kaarima’s mother, Sahar, said she and her husband tried to make Kaarima continue studying but she refused. Sahar believes the government should force children to go to school. “It’s good if the government takes this initiative because kids have their own will.”[51]

Some families are not aware that government schools, with free tuition, are available. Saira, 30, has three sons and one daughter, ages six to 12. Her husband is physically abusive and did not allow Saira to leave the house, but he was away from the home after he found work as a cleaner in a school. “He didn’t want to pay for education, but once he started working, I could sneak out and ask at the church for friends to help our kids go to school,” Saira said. “We didn’t know school was free back then—that’s why the kids didn’t go earlier.” A priest explained that government schools were free, and her husband agreed to enroll the three older children. “When they got admission I cried so much, because I was so happy. When I saw other children in uniform I always wondered, ‘When are my kids going to study?’” Saira never attended school.[52]

Not only are children not required to study, in numerous cases parents and children described situations where teachers urged children to drop out. Palwashay, 16, was in fifth grade and age 14 or 15, when her teacher at government school said she was too old for her grade and should leave. She had low marks and had failed the exam to progress to sixth grade. Her family hopes now to send her to private school.[53]

Shortage of Government Schools

They should open a government school for all of us.

—Ghazal, 16, speaking in a group of 11 out-of-school girls in a poor area of Karachi, July 30, 2017.

There simply are not enough government schools for all children to have access to one. Even in Pakistan’s major cities many children cannot reach a government school on foot in a reasonable amount of time and a safe manner. When families can access a government school, they often find that it is overcrowded.

“The government needs to spend more money and open more schools,” said the head of an NGO working with out of school children. He described an area where his NGO worked: “In two union councils, there was one [government] school. An area that size needs five to ten schools.”[54]

In Peshawar, a local government official said the closest government school was a 40-minute walk away. Because of this, she said, most children start school late, at ages eight to 12, because parents wait for them to be old enough to walk to school on their own.[55] Some parents struggle to pay for a nearby private school for the first year or two of education while they wait for children to become old enough to travel alone to more distant—and more affordable—government schools.[56]

Pakistan has many more boys’ school than girls’ schools, despite the greater safety concerns and restrictions on freedom of movement many girls face.[57] On a national level, in 2016 the government reported equal numbers of middle schools for boys and girls, but major disparities in the number of girls’ primary schools (66,000 girls’ schools out of 165,900 total) and secondary schools (13,400 girls’ schools out of 32,100 total).[58] The disparities become even greater at the level of professional colleges and universities.[59]

In some provinces and local areas, disparities can be higher. For example, in Balochistan there are more than twice as many schools for boys as for girls.[60] A similar disparity exists in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa: “If you have ten schools for boys, you have five for girls,” an education expert from the province explained.[61] Another expert described an area with 14 high schools for boys and only one for girls.[62]

Aisha, around age 30, lives with her husband and their six children in an area of Peshawar where the nearest government school for boys, offering nursery school through 10th grade, is less than a five-minute walk away. The nearest government school for girls is a 30-minute walk and goes only through fifth grade. Aisha’s daughter quit school at age nine because of her parents’ concerns about her safety walking to school.[63]

Many neighborhoods are education deserts for poor families. “I could send them if there was a government school,” said Akifah, 28, a mother of three children, ages ten, eight, and seven. The family had moved from a village near Multan to Karachi three years earlier, looking for work, and had no choice but to settle in an area where there are only private schools the family cannot afford, but no government schools within reach.[64]

The distance to school often increases as children get older, especially for girls. Schools are more likely to be gender segregated as children get older, and there are fewer schools for girls than for boys. If a primary school is nearby, secondary school is often further, and high school further yet, due to smaller numbers of girls’ schools at the higher levels. The government has acknowledged this gap. For example, the Balochistan provincial education plan identifies it as a barrier for girls, saying, “School availability is further limited by ‘upward bottlenecks’ created by the drastic reduction of the number of schools at the middle and secondary levels, leading to the exclusion of many children, especially girls.”[65]

This gap makes the transition from fifth to sixth grade impossible for many girls. Beenish, 14, left school after fifth grade, because the closest secondary school was a 10 to 15-minute drive. “Both of my parents want me to study,” she said, explaining they would allow her to continue if there was a school nearby. But, she said, she is not allowed to walk through the bazaar, which is on the route to the government secondary school, because her family sees it as unsafe, and the family cannot afford to pay for her transportation. She longs to return to school: “I wake up, I pray, I read the Quran, and I do housework—that’s my day,” she said. “My request to the government is to upgrade the primary school to the secondary level so I can continue my studies.”[66]

Girls face another difficult transition when they complete 10th grade. In Pakistan, 10th grade ends with an examination called a secondary school certificate, or SSC. After passing the SSC, students who wish to continue studying go on to a different school, often referred to as an intermediate college, where 11th and 12th grades are taught. Government colleges are in short supply.

Ghazal, 16, lives in a poor area of Karachi. There are two government schools within walking distance of her home, and she completed 10th grade. But to continue she would need to go to a college, and the nearest government college is a half hour drive away, an insurmountable barrier to her poor family. “We don’t have money for more,” she said flatly.[67]

Government colleges, where children study beyond 10th grade, are few and far between, which creates not only barriers in terms of distance, but also fierce competition for admission. “It is competitive to get into government colleges,” the principal of a private school explained. “If children have poor marks, they go to a private college.”[68]

“My hope is that they make government colleges in this area—that is our main issue,” said Asima, 16. “There is one lakh of population here [100,000 people] and no institution for higher learning nearby. The government should take this into account and open an institute here.” She said government schools in their neighborhood go only to eighth grade. She studied to eighth grade at government school, then attended private school for grades nine and ten, but now faces dropping out because her family will only permit her to continue if she can find a job at a college and pay the fees herself. The closest government college is four or five kilometers away, and the family cannot afford for her to travel there by rickshaw.[69]

Urban Versus Rural Differences

The situation is often far harder for families living in rural areas. In villages and the countryside, the distance to a government school can be far greater, and private schools are less likely to be available as they often struggle to earn a profit outside of cities and thus are less likely to fill in gaps created by lack of government schools. Some interviewees said there was no school—government or private—in their village of origin.[70]

In rural areas, like cities, government schools are increasingly scarce as children move from primary to secondary to high school. “In every village, there is a government school, but no college, no higher school,” the headmaster of a private school in a small town in Punjab told Human Rights Watch. “There’s nothing past 10th grade. It’s 13 or 14 kilometers to a college [for children in villages].”[71]

Asifa, 20, delayed attending school until she was nine or ten years old, because it was a 45-minute walk from her village. “My parents said, ‘If you are interested enough you can walk there.’ Whoever wanted to went,” she said. “I found it too far. The path is lonely and isolated and there have been cases of two or three kidnappings in that area…. But then I realized I needed to study so I convinced my parents and I got friends to go so we walked to school together.” The school only went through eighth grade, so after that her only option was to go live with her sister in a town where grade nine and ten is available.[72]

Mina, 22, wanted to be a doctor, but in her village the only way to attend ninth grade is to travel to a college in a town a 45-minute drive away. “I left school because the science teacher wasn’t available until late and I couldn’t come home so late,” she said, explaining the class ended at 6 or 7 p.m. “I asked them to move the time, but the teacher said no.”[73]

Corruption

Corruption is pervasive in Pakistan, which is ranked 117 out of 180 countries on the 2017 Transparency International Corruption Perception Index.[74] Corruption is a major issue in the government school system.

One of the most pervasive forms is bribery or nepotism in recruitment. Some people simply purchase teaching positions. The director of a community-based organization said that the bribe paid to secure a government teaching position varies but averages around 200,000 rupees (US$1,905). “For the last five years, everyone has to pay. It’s worth it just for the salary—it’s an investment. This has an impact on the quality of the teaching—there’s no teaching. Even the building is being used by the landlord in that area in some places for his own purposes. He’s a powerful man—no one dares challenge him.”[75]

Others obtain jobs through political connections. “I did a BA in arts and have a certificate in teaching—and then an MP from this area helped me,” said a government school headmaster, explaining how he obtained his position. “[Government recruitment] is done on a political basis. Maybe 10 percent is on merit.”[76]

An education expert explained that politicians put people loyal to them into positions in the education system not only for bribes, but also for political influence, as teachers can play a role in elections. “They mobilize people, they help fix elections,” he said. “Teachers are influential people.”[77]

When people purchase a teaching position, they do not necessarily teach. “Everywhere you’ll find a government school—the building is there, the teacher is on the payroll, but there is no teacher and no students,” the director of a community-based organization said. “I personally know many teachers who have other jobs. They are earning 60,000 rupees a month [$571]. They have to give some to the district education officer—it varies, sometimes 10 percent. This is a pattern.” He said there is nothing communities can do: “Teachers are political appointments. They have paid money to get these appointments. There is no pressure because these people cannot be pressured.”[78] UNESCO in 2017 cited findings regarding diverted funds, over 2,000 fake teacher identity cards, and 349 “ghost” schools.[79]

The impact of corruption is particularly devastating in rural areas. “There is pressure on principals in cities to enforce some things,” a staff member at a private school said. “But in the villages sometimes the principals don’t even show up.”[80]

“At least in Karachi the government [education] system is functional,” the director of a community-based organization said. In rural areas, particularly in Sindh and Balochistan, he said there was no pressure on government officials to deliver education effectively, describing local government agencies as “non-functional.” “[A] school is there, but no teachers and no students,” he said.[81]

There is also corruption within schools. “There was a girl in the class who was really dull, but she paid 3,000 rupees [$29] and came first,” said Beena, 40. “My niece cried a lot and said, ‘Why couldn’t you pay so I could come first?’” The girl’s mother added: “The teacher asked for money, but I couldn’t give it, and then [my daughter] passed matric, but with a D.”[82] Beena added: “My friend’s son did well—he studied for his matric. His teacher said, ‘If you do something for me—if you pay us 3,000 rupees—we’ll pass you.’ He said, ‘If I’m doing well, why should I pay?’ Then he failed on three out of four papers at his intermediate course in 12th grade and he got discouraged and left.”[83]

Corruption is an issue in both government and private schools, and some parents said that demands for bribes are more of a problem in private schools, perhaps because of the low salaries.[84]

High Cost of Education

The government doesn’t help the poor. We can’t educate our children, and we can’t feed ourselves.

—Rukhsana, 30, mother of three, with a husband rarely able to work due to illness, Karachi, July 2017.

For most of Pakistan’s families, education costs money.

The decision whether to charge fees at government schools is taken at the subnational level, resulting in a patchwork of different practices. In Sindh, most interviewees reported that government schools did not charge fees. In Punjab, interviewees consistently said they paid fees at government schools, most frequently 10 rupees ($0.09) per month for pre-school classes, and 20 rupees for children in primary school.[85] In Balochistan, a government teacher said her school charged an annual admission fee of up to about 30 rupees ($0.29) and local businesses sometimes assisted children whose families struggled to meet the costs.[86] Children must also pay for exam fees, which can be about 20 rupees at primary level at 30 rupees at secondary level ($0.19 and $0.29).[87]

Government schools are also not automatically less expensive than private schools when you take into account associated costs, which may include registration, exams, books, uniforms, and transport. Private schools often have fewer associated costs, for example for books and uniforms, and may offer discounts on fees. Private schools may also be closer, eliminating or reducing transportation costs.

Costs, even if small, put education out of reach for poor families, and there are many poor families in Pakistan. In 2016, the government set a new “poverty level,” an indicator designating adults subsisting on under 3,030 rupees per month ($29) as living in poverty. Using this benchmark, the government in 2016 determined that about 60 million Pakistanis—6.8 to 7.6 million families—were living in poverty, about 29.5 percent of the country’s population.[88]

Children often switch between government and private school for financial reasons. “My children were in private school initially,” said Pariza, 44, mother of eight. “But the switched to government school because we didn’t have the money for private school.”[89]

Associated Costs of Government Schooling

Parents said sending a child to government school, even at the primary level, cost as much as 5,000 rupees per year in associated costs ($0.48).[90] “The school may be free, but there are always demands for money for something or the other,” said Zarifah, a mother of five. “Copies, stationery, every day there is a new expense. A school bag alone costs 500 rupees [$4.76]…. Every day, every day, it’s something.” Zarifah’s oldest daughter studied to second grade but the family took her out of school because of the expense. Zarifah says she would like to send all her children to school, “but our resources are limited.” She adds: “I cannot send just one child to school as this would be unfair to the other children. They will feel hurt at being left out.” Zarifah’s oldest daughter now studies the Quran with a neighbor; the other children are not in education.[91]

Government schools often provide some, but not all, of the textbooks children need and families must also pay for school supplies. “Some books are provided, and some we buy,” said Aqiba, 18, discussing her family’s struggles to keep Aqiba’s two younger siblings in government school. “They keep adding new books every 15 or 30 days that we have to buy. For example, they added a coloring book recently. We spend 3,000 rupees [$29] per month for books.”[92] Several families estimated that it cost 500-600 rupees per year ($5-6) per child in school supplies for them to send their children to government primary school.[93] Others said the cost was much more, as they had to buy replacements and new notebooks throughout the year.[94]

Uniforms can cost over 1,000 rupees ($9.52).[95] Children who cannot afford uniforms may be excluded from school. For girls, parents must also buy a dupatta [scarf] which one mother said cost another 750 rupees ($7).[96] Students may need several uniforms per school year, and may need uniforms for different seasons.[97] A few government schools give free uniforms to selected students, but such assistance is rare.[98] Shoes cost about 500 ($4.76) rupees new, or perhaps half that if you can find them used.[99]

Paveena, 13, said only one girl in her extended family ever went to school. “My six-year-old cousin really cried for it, so her older brother put her in [school],” Paveena said. “But she only went for a month. She would leave the house at 7 a.m., reach the school at 10 a.m. [But] she was going in her home clothes, instead of the uniform, so the teacher took her out.” Paveena said the uniform cost 1,000 rupees ($9.52) and the family could not afford it. “We really want to go to school, but we don’t have the means.”[100]

Muskaan lives in a neighborhood of Lahore where she says the nearest government middle school for girls is a 15 to 20-minute trip by rickshaw. To make the trip every day would cost 3,500 rupees ($33) per month.[101]

Ann finished eighth grade at a school near her home but would have to travel by rickshaw to reach a school teaching ninth grade. A rickshaw would cost 40 rupees each way ($0.38). Her mother is a tailor, her father a construction worker, and she has three brothers. “I assessed my situation myself and saw the issues with transportation and expense for transportation,” she said. “So, I decided not to pursue it. Then I did housework instead.”[102]

Higher grades are more expensive than lower grades, even in government colleges, in terms of both tuition and associated costs. “For science classes for the matric [10th grade exam] you have to buy special things, like test tubes for 500 rupees [$4.76] each,” said Alima, whose daughter is in 11th grade. “You need frogs. We can find them for free but at this time of year you can’t find them. They sell them for 200 rupees [$1.90]…. I had to look for a frog for two days on the ground, but I couldn’t find one. I went to a fish seller and he said he would get me one for 100 rupees [$0.95]. My daughter needed it for the science practicum class.” Alima’s daughter also had to contribute 500 rupees ($4.76) toward a science set used by the class.[103]

Madrasa and Informal Tuition as Alternatives to School

Tutoring is sometimes seen as a more affordable option for parents who cannot afford the cost of school.[104] Madrasas are also frequently used as an alternative for girls not able to attend school.[105] Some children attend madrasa in addition to regular school.

Madrasas and tutoring are often closer and cheaper than school. Shumila, 12, said she and her sisters could only attend madrasa because there was no government school for girls (the closest was a 25-minute walk away) in their neighborhood in Quetta. There was a private school a 10-minute walk away that they could not afford, and six or seven madrasas, including one a two-minute walk from their home which was free.[106]

Low cost tutoring is often available. Some madrasas charge fees, but many are free. Both tutoring and madrasas are generally free of associated costs that come with government and private schools. They are also typically easier for children to join, often accepting children on a rolling basis without administrative requirements such as identification and birth certificates.

The lines between a madrasa education and informal tutoring can be blurred. Asadah, 12, is the oldest of six children in her family. She left school after second grade, because the family could no longer afford the expense, and she was needed to help with chores at home. She has managed to go back to studying by attending Quran lessons at a neighbor’s house every morning; her family pays the neighbor 100 rupees per day ($0.95). She is the only child in the family in any type of education. “I then come home and teach my siblings,” she says.[107]

While madrasas and tutoring can provide some education for children who otherwise would go without, they are not an adequate substitute for school. They do not generally teach a full curriculum, and typically lack a path for transitioning students to the formal education system or helping them obtain formal educational qualifications. Students at madrasas often learn only religious subjects. Children attending informal tuition learn whatever the teacher chooses to teach, in whatever time the child shows up.

Najiba, 12, was unable to go to school because there is no government school in her area and her family cannot afford private school. She went to madrasa instead, six days a week for three hours a day, but studied only the Quran, which she said she has now finished.[108]

Sahar, 34, sends three of her children to madrasa, two in lieu of regular school and one in addition to regular school; the family receives a discount at the madrasa because they are poor, so they pay 600 rupees ($6) per month for all three children.[109]

Busrah, 17, lives in a poor fishing community in Karachi. She attended a private school that cost 600 rupees ($6) a month through fifth grade. When her family could no longer pay, she moved to a government school for grade six. “I didn’t complete sixth grade,” she said. “I just didn’t think the place was right. At private school the teacher used to focus on the students but at government school they didn’t.” After leaving the government school, Busrah joined a madrasa, but left after a year. “They had this whole concept of purdah, but I can’t do this because I have to fetch water, so that didn’t work out,” she said, explaining that the madrasa required girls to cover their whole body, including wearing gloves and socks, anytime they were outside their home. “It’s very hot.”[110]

Quality of Education

There are not enough good quality schools [in this area]. Parents get disheartened and take kids out.

—Career counselor at a youth center in a poor area of Karachi, July 2017.

Poor families, unable to afford elite private schools, are left with the options of government schools or low-cost private schools. Parents in this situation often expressed concerns about the quality of education. Some felt that the quality was so poor that there was no point sending children to school at all.

The government itself acknowledges concerns about poor quality government schools. For example, the Balochistan government writes: “The quality of education also remains poor and the exponential growth of private schools in the province indicates the low levels of confidence in public sector schooling.”[111]

Quality concerns differ in government versus private schools. In government schools, parents and students complained of teachers not showing up, overcrowding, and poor facilities. At private schools, particularly low-cost private schools, concerns more often related to teachers being poorly educated and under qualified. In both government and private schools, use of corporal punishment and abusive behavior by teachers was widely reported.

Quality Concerns in Government Schools

Families had a range of complaints about government schools, including absent and abusive teachers, violent forms of punishment, overcrowding and insecurity in the schools, poor facilities including lack of toilets and water, and frustrations with the curriculum.

Teacher Absences and Qualifications

Many families complained of teachers being absent from school. “Sometimes students go to school and there’s no teacher, so they miss out on their studies,” said Tehreem, 21, who attended government school before becoming a teacher. “This happens here. I am speaking from experience. Throughout the year they wouldn’t teach us, and then for the last three months there would be all this pressure before exams. In a week, they would come once or twice. Mostly this is the case in primary schools—this a crucial development time for children, but the teacher is not there.” Of her current unpaid work in a free tuition center, she said, “We feel happy doing this, and we want these children to get a better education than what we got in government schools.”[112]

Atifa, 16, and her sister, Hakimah, 17, live in Karachi. They both left school after fifth grade. “A lot of times the teacher showed up late or he would not show up at all. We would just go and sit and then come home,” Hakimah said, about their primary school. Their younger sister, Zafra, 12, left school after grade two or three. “I had the same issues—teachers wouldn’t show up. I left because of that—I didn’t feel I was learning.”

After completing fifth grade, Atifa and Hakimah tried to register for secondary school. “We’ve been trying to get admission there for a while,” Hakimah said, of the government secondary school nearest their home, a 15-minute walk away. “But we would go, and they would say, ‘The headmistress is not here—come another day.’ We went three or four times and then gave up.… Then finally we tried the private school, but we found it cost too much money for us—700 or 800 rupees per student per month [$7-8].”[113]

Many interviewees pointed to teacher absences as one of the key factors in their preference for private schools. “In private schools they have to always show up,” said Layla, 50, a grandmother, after explaining that teachers are often absent at the nearby government school.[114]

Although teachers in government schools typically earn more than private school teachers, some experts cited poor salaries as a reason for teacher absenteeism in government schools, along with the corruption issues discussed above. “The issues are teacher salaries—they are paid badly and there is no job security because now the government is giving short term contracts,” a labor rights expert in Punjab said. “If teachers are paid well in government schools, the quality will improve.” He said teacher salaries start at 15,000 rupees ($143) per month—the equivalent of the national minimum wage.[115] Government teachers interviewed for this report reported earning monthly salaries ranging from the 8,000 rupees ($76) paid to a primary school teacher in Karachi to a high school teacher in Peshawar who said she earned 78,000 rupees ($743) per month.[116]

The director of a community-based organization said that the Sindh government had discussed creating a biometric system using fingerprints to track teacher attendance, but it was never implemented. “There was no interest from the high level. There is no shortage of money in the education system in Sindh, but it is not being used properly.”[117] In Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, a teacher said that a biometric system for monitoring teacher attendance had been implemented and had significantly improved teacher attendance.[118]

Experts and families also had concerns about teachers’ qualifications and motivation. “There are a lot of challenges,” the principal of a government school in Karachi said. “Illiterate teachers with only a matric are being appointed as teachers. They don’t know how to learn and teach. We face this a lot.” He said that on paper the government requires primary school teachers to have completed a one-year post-matric training course, but in recent years people without this qualification were being appointed. “The main problem was politicians,” he said. “Politicians appoint their family and party workers as teachers…. The politician thinks about his voter and his own benefit. He has to reward the people who support him.”[119]

“Teachers in government school just eat sweets while the children play outside—they don’t focus on the kids,” said Maryan, 36, explaining why she and her husband sent their children to private school. When Maryan’s husband lost his job as an electrician in Saudi Arabia, they could no longer afford the cost of private school, and the children stopped studying.[120]

Overcrowding

Government schools often suffer from unmanageable class sizes. Class sizes in government schools are meant to be limited—in some areas, for example, to 35 students.[121] But children and experts said classes are often much larger—50 to 80 students, and sometimes more.[122] “In government schools, there are very few teachers,” a worker at a youth center in Karachi said. “There will be one teacher who is supposed to be teaching two sections. One section is supposed to be 35 kids but usually it is more—45, 50—so you have one teacher for 90 to 100 kids.”[123]

A teacher in Peshawar said she struggled to teach high school subjects to classes of sometimes over 60 students.[124] Another government teacher, in Peshawar, said she had 120 students: “too many.” She also complained of a grueling schedule: “One teacher can’t teach eight classes in a row,” she said.[125]

Overcrowding drives children out of government schools. “At the government college and government school it’s so crowded it’s chaotic and you can’t focus mentally,” said Marzia, who helps run an informal school in her family’s home in Karachi.[126]

Maryam has worked at a private school for nine years. She attended government school for her own education, and said that overcrowding has grown worse:

This is recent. In the past, before 2000, government schools were seen as very good, but the reputation of government schools has gone down because there are so many students in one class. How can teachers focus on this many kids?... I went to government school and was really happy. My sister is 14 years younger. She found it a different place, not good. When I was learning … if I had a question I could ask as many times as I want. Now, if you learn, fine. If you don’t, the teacher won’t explain again.[127]

Overcrowding can lead to government schools turning children away. A headmaster of a private school in Punjab said the government school in his area refuses to enroll new students. If they didn’t, he said, “I wouldn’t have to run a private school.”[128]

Because of overcrowding, many schools have several shifts a day. This shortens the school day, typically to only four hours, making it impossible to cover a full curriculum.[129]

Water, Sanitation, and Facilities

If there are teachers, there are no classrooms. If there are classrooms, there are no teachers.

—Government teacher in Peshawar, August 2017

Government schools are often in poor physical condition, unable to offer a safe learning environment. “The education policy is not implemented,” the head of an NGO working with out of school children said. He described specific rules about the number of rooms and chairs schools should have but said these are not followed. “The laws and policies are there, but they are not implemented because there are no resources,” he added. “We are not in a position to upgrade our education system.”[130]

“There is not enough money for buildings, toilets, washrooms, furniture,” the headmaster of a government primary school in Karachi, who has worked in the government education system for 25 years, said. “Every government school faces these problems.”

He had recently been assigned to a different school where the situation was worse than at his previous school. “There are no windows or doors—just a ceiling and walls. No chairs—we are trying to arrange chairs. Kids sit on the floor. There is no water at the school—kids go home to have water. There are no washrooms or toilets—they go back home [if they need the toilet].… Naturally it does affect our ability to teach.”[131]

An education expert pointed out that poor infrastructure, particularly lack of toilets, creates greater difficulties for girls than for boys. “Schools in rural areas are not built for girls’ needs,” he said. “There is no toilet, no water, no boundary walls, no security.”[132]

Thirty-seven percent of schools do not have basic sanitation or toilet facilities.[133] Girls who have started menstruation are particularly affected by poor toilet facilities. Without private gender-segregated toilets with running water, they face difficulties managing menstrual hygiene at school and are likely to stay home during menstruation, leading to gaps in their attendance that undermine academic achievement, and increase the risk of them dropping out of school entirely.[134]

“There is an issue with drinking water in the school,” said Zafira, 15, a ninth-grade student in government school. “Generally, in this area there are water shortages, so sometimes for a week there is no drinking water at school.” Zafira said students bring their own water or go without.[135]

Poor facilities also affect school staff. Shazia, 24, is a private school teacher. “I have friends who are government teachers,” she said. “They said I should work for the government.” Shazia decided not to apply. “There are none of the facilities that I get here—electricity, a generator, furniture. The salaries are high, but the infrastructure is very bad,” she said. “In so many schools there are no toilets and no clean water. These are the reasons that I didn’t want to work there, and my in-laws didn’t want me to work there.”[136]

Quality Concerns in Private Schools

Experts and educators raised concerns about the quality of education in some low-cost private schools. One expert said, “My real concern is low-cost private schools.... Kids spend six or ten years in these schools and learn nothing.”[137]

Teacher Qualifications, Training, and Salaries

Private schools often maximize profits by paying teachers as little as possible, which results in them hiring teachers with few qualifications.

“In private schools, teachers get very low salaries,” the head of a community-based organization told Human Rights Watch, adding that in the area where his organization works private school teachers earn 1,500 to 3,000 rupees a month ($14-28). “Minimum wage [for government teachers] is 15,000 [$143] so they are getting one tenth or one fifth as much.” He said that the private school teachers are usually required only to have completed 10th grade, and most are women.[138]

A government teacher in Balochistan contrasted her terms of employment—18,000 rupees per month salary ($171) with an annual raise, pension, health benefits, annual and parental leave, and annual training—with that of private school teachers she knew, who she said earned 4,000 to 5,000 rupees per month ($38-48) with no benefits.[139] A government headmaster said that while physical conditions are generally better in private schools, he wouldn’t work in one due to low salaries and lack of benefits.[140]

Experts said conditions of employment are similar for teachers in NGO schools: “You have one teacher with 20 students in one room. The teacher earns 5,000 rupees [$48] a month…. [I]nformal school teachers should have proper training and higher salaries.”[141]

Lack of Government Regulation of Private Education

Private schools are obliged to register with and obtain a certification from the relevant government authority. But oversight, both through and after the registration process, is sparse. “They are registered with government but not standardized,” the head of an NGO said.[142] An education expert pointed to the role of some government officials as owners of companies operating private schools as a barrier to monitoring, citing examples where these politicians had intervened to block government from more closely regulating private schools in ways that might reduce profits.[143]

Government officials inspect private schools periodically, but inspections are often cursory. The headmaster of a private school in Punjab said the government inspects his school, “But they are not effective. They come, but they are not doing a good job.”[144]

“Once or twice a year they come, unannounced,” another private school principal said. “They come for a half hour. They want tea and to be entertained. You have to please them or they will say that your school is not good. Once I made the inspector wait and he got mad and left and said, ‘I will write a bad report.’ My colleague went to his house and gave him 25,000 rupees [$238] and we got a good report.”[145]

Private schools are free to choose their own curriculum, though some use the government curriculum. “We set the curriculum—no one tells us what to teach,” a headmaster of a private school explained.[146] “There is no monitoring of the curriculum,” the head of an NGO said.[147] As they prepare students for government exams after sixth grade, some private schools become more likely to use the government curriculum.[148]

Because private schools are so unregulated, they can vary dramatically in terms of not only teaching quality but also the adequacy and safety of the facilities, with some low-cost private schools in very poor facilities.

There also exists an entire world of private tutoring, often providing additional help for children in school, but sometimes the last resort for children unable to access schools. Tutoring often consists simply of a teacher—usually a woman or girl—setting up classes in her home. While some tutors are motivated by philanthropy, other are businesses, and such tuition is often entirely unregulated. Private tuition does not provide children with a path for transitioning into a school or obtaining educational qualifications. Parents who are uneducated likely have difficulty assessing the quality of private tuition and are vulnerable to exaggerated claims by tutors.