In the week of the 60th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, three media workers – a journalist, a publisher and his wife – will complete nine months in prison in Sri Lanka. The three are being held under the country's sweeping anti-terror laws, aimed at the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, which has been fighting for an independent Tamil state for nearly three decades. They are the latest victims of the increasingly authoritarian government of President Mahinda Rajapakse.

A columnist for the island's Sunday Times, JS Tissainayagam is one of the few journalists to be charged under the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) in its almost 30 years on the statute books. His crime? The government cites two articles in a July 2006 editorial in the North Eastern Monthly. One, under the headline, "Providing security to Tamils now will define northeastern politics of the future," says, "It is fairly obvious that the government is not going to offer them any protection. In fact it is the state security forces that are the main perpetrator of the killings."

Passages such as this are classic free speech, yet Tissainayagam is currently on trial at the high court in Colombo. There have been many irregularities in the case, such as the refusal of the government to allow private consultations with his lawyer, which is the basic right of any detainee.

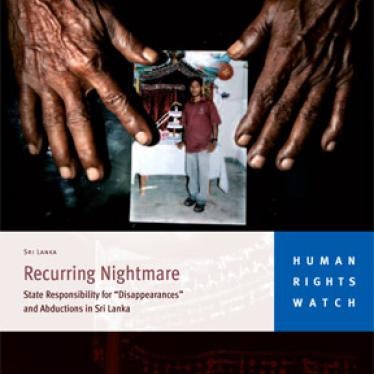

Tissainayagam is not the only critic of the government's military campaign, which started afresh in early 2006. Human Rights Watch and others have reported on the government's responsibility for enforced disappearances, targeted killings, detention of displaced persons, and unnecessary restrictions on humanitarian aid. The LTTE – progenitor of suicide bombings – has continued to target civilians, particularly moderate Tamils, place strict limits on basic freedoms in areas under its control, prevent civilians from fleeing combat areas, and forcibly recruit adults and children as soldiers.

In echoes of the discredited rhetoric of President Bush, in December 2006 President Rajapakse asked Sri Lankans to make a choice – either to be for the "war on terror" or against it. Since then, critics of the government have been threatened, attacked, disappeared, killed or jailed. The attacks have spread to foreign governments and international organisations who raise human rights concerns with Sri Lanka. The UN secretary general, Ban Ki-moon, Sir John Holmes, UN under-secretary general for humanitarian affairs, Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, the International Crisis Group, and the International Commission of Jurists have all been accused of essentially being in league with or dupes of the LTTE after criticising the government on rights.

These attacks are taking place in a country where a potent cocktail of ethnicity, language and, to a certain degree, religion have long polarised the majority Sihalese and minority Tamil populations. And while the Sri Lankan government certainly has a responsibility to fight terrorism and criminality, it must do so consistent with international human rights law. Those in the LTTE responsible for horrific attacks like the 1996 bombing of the Central Bank building in Colombo and numerous other attacks targeting civilians before and after must be punished. But arbitrarily arresting and detaining journalists and others will not root out terrorism. On the contrary, acts like these will only succeed in alienating those who also oppose the LTTE's tactics.

Ironically, President Rajapakse was himself once a human rights activist. In the aftermath of a leftwing Sinhalese insurgency in the late-1980s he worked closely with an organisation to collect information for family members of the "disappeared." Tissainayagam worked on the report which Rajapakse took to the UN in Geneva, demanding action against those responsible. Today Rajapakse's government angrily denounces the UN and its mechanisms when they take the government to task.

Rajapakse makes two arguments to defend himself against critics: first, that the government is fighting terrorism, so critics must not be genuinely committed to fighting terror. Second, since he and his government were elected they have the legitimacy and right to pursue their policies. Neither of these points, of course, provides any excuse for jailing peaceful critics, engaging in forced disappearances, or denying access to the UN to provide humanitarian aid to hungry Tamils trapped in the fighting in the north. And if press freedom is a fundamental part of a functioning democracy, then the vibrancy of Sri Lanka's democracy must be questioned. According to Reporters sans Frontieres, the media watchdog, Sri Lanka has slipped to 165 of 173 countries in its global ranking of press freedom for 2008 – below Zimbabwe and Sudan.

The Sri Lankan should simply release Tissainayagam, the publisher and his wife. It would be a fitting way to show that it remains a vibrant democracy. But this won't happen without sufficient pressure from Sri Lanka's friends in the UK, EU, US, Canada, Japan and India. They need to let President Rajapakse know – loud and clear – that they will not stand idly by while Sri Lanka's human rights record continues to deteriorate.

Charu Lata Hogg is South Asia researcher at Human Rights Watch