Recurring Nightmare

State Responsibility for "Disappearances" and Abductions in Sri Lanka

Karuna group

Eelam People's Democratic Party (EPDP)

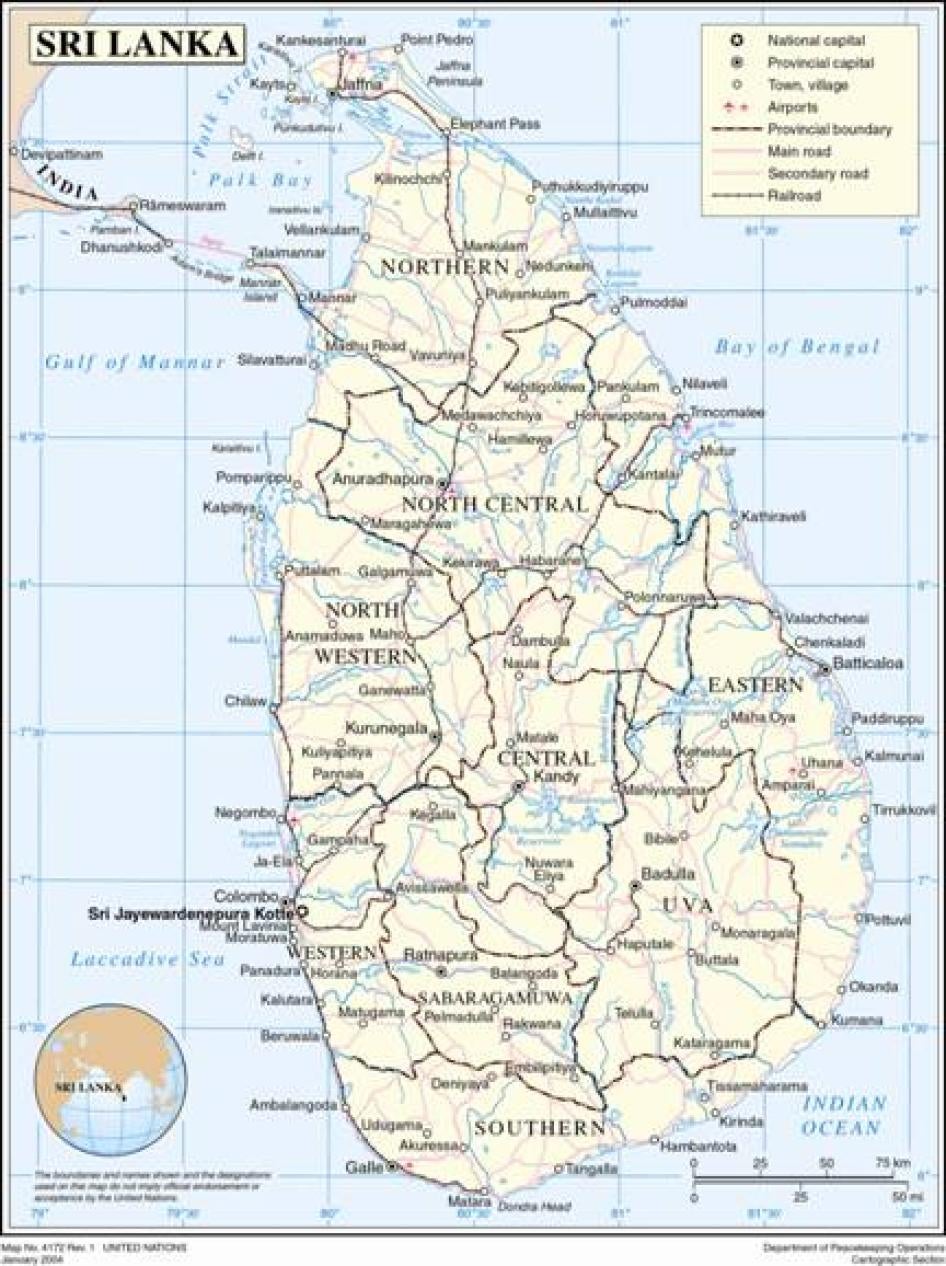

Map of Sri Lanka

I. Summary

His father opened the door, and the men pushed him aside and then forced us and the children into one of the rooms. Junith Rex came out of his room, covering himself with a bed sheet, and the men grabbed him by the bed sheet and seized him. They wore black pants, green T-shirts, and their heads were wrapped with some black cloth. Later I found out that they arrived in a van, but they parked it on the main road. They smashed the lights bulbs in the room and dragged him away. They told him "Come," in Tamil. He cried, "Mother!" but we couldn't help him.

- Family member describing the abduction of Junith Rex Simsan on the night of January 22, 2007, following an army search of the house earlier that same day. At this writing, despite repeated inquiries by his family, his whereabouts remain unknown, his fate uncertain.

For instance, take the missing list. Some have gone on their honeymoon without the knowledge of their household is considered missing. Parents have lodged complaints that their children have disappeared but in fact, we have found, they have gone abroad.… These disappearance lists are all figures. One needs to deeply probe into each and every disappearance. I do not say we have no incidents of disappearances and human rights violations, but I must categorically state that the government is not involved at all.

- Sri Lankan President Mahinda Rajapaksa, in an interview to Asian Tribune, October 4, 2007.

The resumption of major military operations between the government of Sri Lanka and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) in mid-2006 has brought the return of a haunting phenomenon from the country's past-the widespread abduction and "disappearance" of young men by the parties to the conflict. With the de facto breakdown of the 2002 Norway-brokered ceasefire between the parties, and its formal dissolution in January 2008, it is likely armed conflict will intensify in the coming year. Unless the Sri Lankan government takes far more decisive action to end the practice, uncover the fate of persons unaccounted for, and prosecute those responsible, then 2008 could see another surge in "disappearances."

Hundreds of enforced disappearances committed since 2006 have already placed Sri Lanka among the countries with the highest number of new cases in the world. The victims are primarily young ethnic Tamil men who "disappear"-often after being picked up by government security forces in the country's embattled north and east, but also in the capital Colombo. Some may be members or supporters of the LTTE, but this does not justify their detention in secret or without due process. Most are feared dead.

In the face of this crisis, the government of Sri Lanka has demonstrated an utter lack of resolve to investigate and prosecute those responsible. Families interviewed by Human Rights Watch all talked about their failed efforts to get the Sri Lankan authorities to act on the cases of their "disappeared" or abducted relatives.

The cost of this failure is high. It is not only measured in lives brutalized and lost, but in the anguish suffered by the survivors-the spouses, parents, and children who may never learn the fate of their "disappeared" loved one. And it is felt in the fear and uncertainty that remains in the communities where such horrific, unpunished crimes take place.

This report provides extensive case material and data about enforced disappearances and abductions since mid-2006. It details the Sri Lankan government's response, which to date has been grossly inadequate. The government shows every sign of repeating the failures of past administrations, making lots of noise-including launching a spate of new mechanisms to investigate "disappearances"-but conducting little actual fact-finding and virtually no prosecution of perpetrators. The report concludes with specific recommendations on how authorities and concerned international actors can respond more effectively. The appendix to this report contains a detailed description of 99 cases documented by Human Rights Watch. A list of 498 additional cases documented by Sri Lankan human rights groups is available at: http://hrw.org/reports/2008/srilanka0308/srilanka0308cases.pdf.

* * *

Under international law, an enforced disappearance occurs when state authorities detain a person and then refuse to acknowledge the deprivation of liberty or the person's whereabouts, placing the person outside the protection of the law.

In Sri Lanka, "disappearances" have for too long accompanied armed conflict. Government security forces are believed to have been responsible for tens of thousands of "disappearances" during the short-lived but extremely violent insurgency from the left-wing Sinhalese nationalist Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) from 1987 to 1990, and the ongoing two-decades-long civil war between the government and the Tamil-nationalist LTTE.

Enforced disappearances have again become a salient feature of the conflict. Figures released by various governmental and nongovernmental sources suggest that more than 1,500 people were reported missing from December 2005 through December 2007. Some are known to have been killed, and others have surfaced in detention or otherwise have been found, but the majority remain unaccounted for. Evidence suggests that most have been "disappeared" or abducted. The national Human Rights Commission (HRC) of Sri Lanka does not publicize its data on "disappearances," but Human Rights Watch learned that about 1,000 cases were reported to the HRC in 2006, and over 300 cases in the first four months of 2007 alone.

"Disappearances" have primarily occurred in the conflict areas in the country's north and east-namely the districts of Jaffna, Mannar, Batticaloa, Ampara, and Vavuniya. A large number of cases have also been reported in Colombo.

Who Is Responsible?

In the great majority of cases documented by Human Rights Watch and Sri Lankan groups, evidence indicates the involvement of government security forces-army, navy, or police. The Sri Lankan military, empowered by the country's counterterrorism laws, has long relied on extrajudicial means, such as "disappearances" and summary executions-in its operations against Tamil militants and JVP insurgents.

In a number of cases documented by Human Rights Watch, family members of the "disappeared" knew exactly which military units had detained their relatives, which camps they were taken to, and sometimes even the license plate numbers of the military vehicles that took them away.

In other cases, groups of about a dozen armed men took victims from their homes, located near army checkpoints, sentry posts, or other military positions. While eyewitnesses could not always identify the perpetrators beyond doubt, they suspected the military's involvement, as it seemed inconceivable that large groups of armed men could move around freely during curfew hours and get through checkpoints without the military's knowledge.

Relatives frequently described uniformed policemen, especially members of the Criminal Investigation Department (CID), taking their relatives into custody before they "disappeared." The police claimed that these individuals were needed for questioning, yet did not say where they were being taken and did not produce the required "arrest receipt." After these arrests, the families did not manage to obtain any information on the detainees' fate or whereabouts.

The involvement of the security forces in "disappearances" is facilitated by Sri Lanka's emergency laws, which grant sweeping powers to the army along with broad immunity from prosecution. Several provisions of the two emergency regulations currently in force create a legal framework conducive to "disappearances." People can be arrested without a warrant and detained indefinitely on vaguely defined charges; there is no requirement to publish a list of authorized places of detention; and security forces can dispose of dead bodies without public notification and without disclosing the results of the post-mortem examination, thus preventing proper investigations into custodial deaths.

Also implicated in abductions and "disappearances" are pro-government Tamil armed groups acting either independently or in conjunction with the security forces. Relatives of the "disappeared" have often pointed to the Karuna group, which broke away from the LTTE in March 2004 and operates primarily in the east and in Colombo. In Jaffna, eyewitnesses to several abductions have implicated members of the Eelam People's Democratic Party (EPDP), a Tamil political party that has long been targeted by the LTTE.

Both groups cooperate closely with Sri Lankan security forces. The military and police frequently use native Tamil speakers, often alleged to be Karuna group or EPDP members, to identify and at times apprehend suspected LTTE supporters. In several cases reported to Human Rights Watch, families said that they were first visited and questioned by the military, and then, usually several hours later, a group of Tamil-speaking armed men came to their house and took their relatives away. On other occasions, the Karuna group and EPDP seemed to be acting on their own-settling scores with the LTTE or abducting persons for ransom-with security forces turning a blind eye.

The LTTE has been implicated in abductions in conflict areas under the government's control, though the numbers reported to human rights groups and the Human Rights Commission are comparatively low. This is not cause for complacency about LTTE practices which, as Human Rights Watch and others have documented elsewhere, include bombings targeting civilians, massacres, torture, political assassinations, systematic repression of basic civil and political rights in LTTE-controlled areas, and other serious abuses. In part, the LTTE abduction numbers are low because it is not the LTTE's primary tactic; the LTTE prefers to openly execute opponents, perhaps to ensure a deterrent effect on the population. LTTE abductions may also be under-reported because the family members of the victims and eyewitnesses are often reluctant to report the abuses, fearing LTTE retribution.

Who Is Being Targeted?

No matter who is responsible for the "disappearances," the vast majority of the victims are ethnic Tamils, although Muslims and Sinhalese have also been targeted. The security forces appear to target individuals primarily because of their alleged membership in or affiliation with the LTTE. Young Tamil men are among the most frequent targets, including a significant number of high school and university students. In other cases, the "disappearances" of clergy, educators, humanitarian aid workers, and journalists not only remove these persons from the civil sphere but act as a warning to others to avoid such activities.

In the north and east, many arrests leading to "disappearances" have occurred during or after military cordon-and-search operations following an LTTE attack. During such operations, the military either has detained people or seized their documents and requested that they report to the army camp or another location to collect them. In both scenarios, some of these people have never returned, and the relatives' efforts to obtain any information on their whereabouts from the military have proved futile.

Particularly in Jaffna, individuals often have been "disappeared" after being stopped by military personnel at checkpoints, or as a result of targeted raids that sometimes followed claymore mine attacks or similar security incidents. In several cases in Jaffna, family members believe that EPDP cadres participated in the raids-judging by the perpetrators' native Tamil speech, appearance, and cars leaving in the direction of EPDP camps.

In the east, Human Rights Watch received credible reports from eyewitnesses and humanitarian aid workers of "disappearances" that took place when thousands of people fled LTTE areas during fighting in late 2006 and early 2007. The army and the Karuna group reportedly screened displaced persons entering government-controlled territory to identify suspected LTTE members. In a number of cases, young Tamil men detained as a result of such screenings then "disappeared."

Particularly in Colombo, and in the eastern districts of Batticaloa, Trincomalee, and Ampara, the lines between politically motivated "disappearances" and abductions for ransom have blurred since late 2006, with different groups taking advantage of the climate of impunity to engage in abductions as a way of extorting funds. While criminal gangs are likely behind some of the abductions, there is considerable evidence that the Karuna group and EPDP have taken up the practice to fund their forces, while the police look the other way.

Human Rights Watch has previously reported on abductions by the Karuna group in the east for the purpose of forced recruitment, including of boys. In many such cases, while the families knew that their husbands or sons were taken away to be used as soldiers, they subsequently received no information on their fate or whereabouts.

Unpunished Crimes

Enforced disappearances are a continuing offense-meaning the crime continues to be committed until the whereabouts or fate of the victim becomes known. The continuing nature of the crime takes a particularly heavy toll, with family members left wondering for months or years or forever whether their loved one is alive or dead. Some of the "disappeared" reappear as corpses showing signs of execution or torture, or turn up alive in detention in police custody or army camps, or simply turn out never to have been disappeared after all. But the great majority never turn up again and are presumed dead, victims of extrajudicial execution or other death in custody.

A critical factor contributing to continuing "disappearances" in Sri Lanka is the systemic impunity enjoyed by members of the security forces and pro-government armed groups for abuses they commit.

Police still do not investigate most of the cases and rarely follow up with families on the progress of cases, claiming they lack sufficient information to identify perpetrators and locate victims. As detailed in this report, however, family members say that even when they provide details to the police that should at least give a start to an investigation-such as the license plate numbers of the vehicles allegedly used in the abductions and the names of people or military units the family believes were involved-police do not follow through.

Figures on accountability released by the government show how little has been done to bring perpetrators to justice. A document provided to Human Rights Watch by the Sri Lankan government in October 2007 mentions only two pending cases against army personnel for unspecified human rights violations committed in 2005-2006, and refers to a recent indictment served on an unspecified number of army personnel for the killing of five students in Vavuniya in 2007. None of the indictments for abductions and "wrongful confinement" mentioned in the document appear to be for abuses committed since mid-2006.

The only known arrests for recent abductions were of former Air Force Squadron Leader Nishantha Gajanayake and another two policemen and an air force sergeant in June 2007. Although Sri Lankan authorities widely publicized these arrests as proof of their resolute action against the abductors and promised to promptly bring the perpetrators to justice, in early February 2008 the suspects were released; it is unclear whether charges against them were dropped.

The Government's Response

Instead of making a diligent effort to investigate and prosecute enforced disappearances, the government of President Mahinda Rajapaksa continues to downplay the scope of the problem. Many official statements suggest there is no "disappearance" crisis at all or, if there is one, the sole perpetrators are LTTE fighters and common criminals. While the government has set up various mechanisms to address abductions and "disappearances," all have lacked the independence, power, resources, and capacity necessary to conduct effective investigations.

Sri Lanka has a long history of setting up mechanisms to address "disappearances" but not following through. Four official commissions of inquiry set up by then President Chandrika Kumaratunga in the 1990s established that more than 20,000 people "disappeared" during armed conflicts in the 1980s and 1990s. Human rights groups believe that the actual figure may be two to three times higher. These commissions identified suspected perpetrators in more than 2,000 cases, but few have ever been prosecuted, and only a handful of low-ranking officers were convicted. Nor have successive governments meaningfully implemented the commissions' recommendations for legal and institutional reforms aimed at preventing "disappearances" in the future.

The Rajapaksa government's response to the surge in "disappearances" starting in mid-2006 appears to be following this pattern. First, the independence of existing government bodies, the Human Rights Commission and the National Police Commission, has been significantly undermined by decisions by the president to bypass constitutional requirements and directly appoint commissioners to these bodies.

Despite the hundreds of alleged "disappearances" reported over the last two years to the Human Rights Commission, it has issued no public reports on the matter, has refused to provide statistics on the complaints it has received, and has tried to downplay the scale of the problem. The monitoring and investigative authority of the Human Rights Commission has also been effectively negated by the obstructive attitude of the security forces and lack of support from the government. As a sign of the HRC's failings, in December 2007 the international body that regulates national human rights commissions downgraded the HRC's status to "observer" because of government encroachment on its independence.

Second, while the government has created at least nine other special bodies to address "disappearances" and other human rights violations-all of them described in the report-as yet none of them have yielded concrete results.

Aside from periodic announcements on their establishment, the government rarely has provided any information regarding the mandate of such bodies, or the progress made in the investigations. The government also has not explained whether it continues to create new bodies because of the inability of previously established mechanisms to deal with the problem, or whether it is simultaneously correcting flaws in existing mechanisms.

Many observers believe that most of these bodies have been established to give the impression the government is taking seriously reports of widespread "disappearances" by security forces even as officials dither in initiating investigations into the cases. The government's continuing dismal record in prosecuting perpetrators lends credence to such beliefs.

The lack of progress in investigations and the failure to halt the abuses is hardly surprising given that, at the highest levels, the Sri Lankan government continues to deny any new "disappearance" crisis or that its security forces are responsible for any significant portion of the violations. Typical in this respect are claims made by Judge Mahanama Tillekeratne, who stated that the abductions were "the result of personal grudges," and that the majority of the missing persons have returned, neither of which claim is substantiated by the evidence.

President Rajapaksa, government ministers, and the government's Secretariat for Coordinating the Peace Process (SCOPP) also have repeatedly dismissed reports of widespread "disappearances" as LTTE propaganda aimed at smearing the state's image. They have claimed that most of the missing individuals have returned, left the country, went into hiding to escape criminal charges, or simply left home and failed to inform their families of their whereabouts-without providing facts to support these contentions.

These claims contradict statements made by some Sri Lankan law enforcement officials, such as the inspector general of the police, and information, albeit limited, that has been released by the governmental commissions, as well as facts and figures publicized by the media and NGOs. Such claims also invite the obvious question of why the government has felt the need to establish so many different mechanisms to look into an allegedly non-existent problem. High-level attempts to dismiss the problem of "disappearances" send a signal to security forces that the government does not take the allegations of their involvement in human rights abuses seriously.

International Response

Various United Nations mechanisms and some of Sri Lanka's key international partners have raised concerns about the high number of enforced disappearances since mid-2006. Senior UN officials visiting Sri Lanka such as the High Commissioner for Human Rights, the Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions, and the Special Advisor on Children and Armed Conflict, have all noted the alarming prevalence of impunity and the failure of law enforcement bodies and national human rights mechanisms to establish accountability. Foreign governments such as the United States and United Kingdom have also spoken out.

Sri Lanka's response to the growing international criticism has taken two forms. The government has intensively lobbied international organizations and bilateral partners, emphasizing improvements in the human rights situation and its willingness to cooperate with UN officials and human rights specialists. At the same time it has fiercely attacked its critics, including the very same UN representatives, accusing them of being, at best, ignorant of the situation and, at worst, LTTE sympathizers.

The continued refusal of the Sri Lankan government to acknowledge and adequately address the wide range of human rights violations has led to growing national and international support for the establishment of a UN human rights monitoring mission to investigate and report on abuses by government forces and the LTTE throughout the country.

The European Union and more recently the US government have joined the calls of domestic and international NGOs for establishing an international monitoring mission under the auspices of the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. During her October 2007 visit to Sri Lanka, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Louise Arbour expressed the willingness of her office to work with the Sri Lankan government toward establishing such a presence.

The Sri Lankan government has thus far rejected the proposals for any international monitoring mechanism. This response belies the government's claims that it is taking the measures necessary to protect the rights of all its citizens.

Key Recommendations

- The Sri Lankan government should publicly acknowledge the scope of "disappearances" in the country and the continuing role of security forces in committing such abuses.

The Sri Lankan government will not make meaningful progress in ending "disappearances" until it takes the problem seriously and is seen to be taking it seriously. However many new mechanisms the government creates, their efforts cannot be expected to succeed when senior officials deny there is a serious problem. An essential starting point is unambiguous acknowledgment of the problem, and of the role of security forces and pro-government, non-state armed groups in perpetuating the practice.

- The Sri Lankan government should reform detention procedures to ensure transparency and compliance with international due process standards.

In order to stop the spree of new "disappearances," the government should ensure that all persons taken into custody are held in recognized places of detention, and each facility maintains detailed detention records. Detained individuals must be allowed contact with family and unhindered access to legal counsel; they should promptly be brought before a judge and informed of the reasons for arrest and any charges against them.

- The Sri Lankan government should vigorously investigate and prosecute perpetrators of "disappearances."

Lack of accountability for perpetrators is one of the key factors contributing to the crisis of "disappearances." The authorities must vigorously investigate all cases of enforced disappearances and arbitrary arrests, including those documented in this report-until in each case the fate or whereabouts of the person is clearly and publicly established. Those responsible for "disappearances" and abductions, be it members of government security forces or members of non-state armed groups, must be disciplined or prosecuted as appropriate.

- The government and the LTTE should cooperate with the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights to establish and deploy an international monitoring team to report on violations of international human rights and humanitarian law by all parties to the conflict.

Deployment of an experienced international monitoring team would save lives, curtail abuses, and promote accountability. Here, the burden rests not only with the Sri Lankan government and LTTE, but also with concerned international actors. The latter should make it clear that they view the Sri Lankan government's position on deployment of such a team as an important test of its commitment to human rights and its willingness to take real, rather than feigned, measures to address continuing problems. Sri Lanka's international partners, in particular India and Japan, should make further military and other non-humanitarian assistance to Sri Lanka contingent on government efforts to halt the practice of "disappearances" and to end impunity, including its acceptance of an international monitoring team.

International monitoring has proven particularly effective in dealing with the problem of large-scale "disappearances." With sufficient mandate and resources, the monitoring mission could achieve what the government and various national mechanisms have failed to do-establish the location of the detainees through unimpeded visits to the detention facilities; request information regarding specific cases from all sides to the conflict; assist national law enforcement agencies and human rights mechanisms in investigating the cases and communicating with the families; and maintain credible records of reported cases.

Detailed recommendations to the Sri Lankan government, the LTTE, and the international community are found in the closing chapter of this report.

Note on Methodology

This report is based on field research carried out in Sri Lanka in February, March, and June 2007, and follow-up research through January 2008. Human Rights Watch conducted over 100 interviews with families of the "disappeared," as well as dozens of interviews with human rights activists, lawyers, and international agencies working in Sri Lanka. Human Rights Watch visited Colombo and its environs, and the districts of Batticaloa and Jaffna.

Following the visits, Human Rights Watch communicated closely with local NGOs and international organizations working in Sri Lanka to update the information and obtain new data.

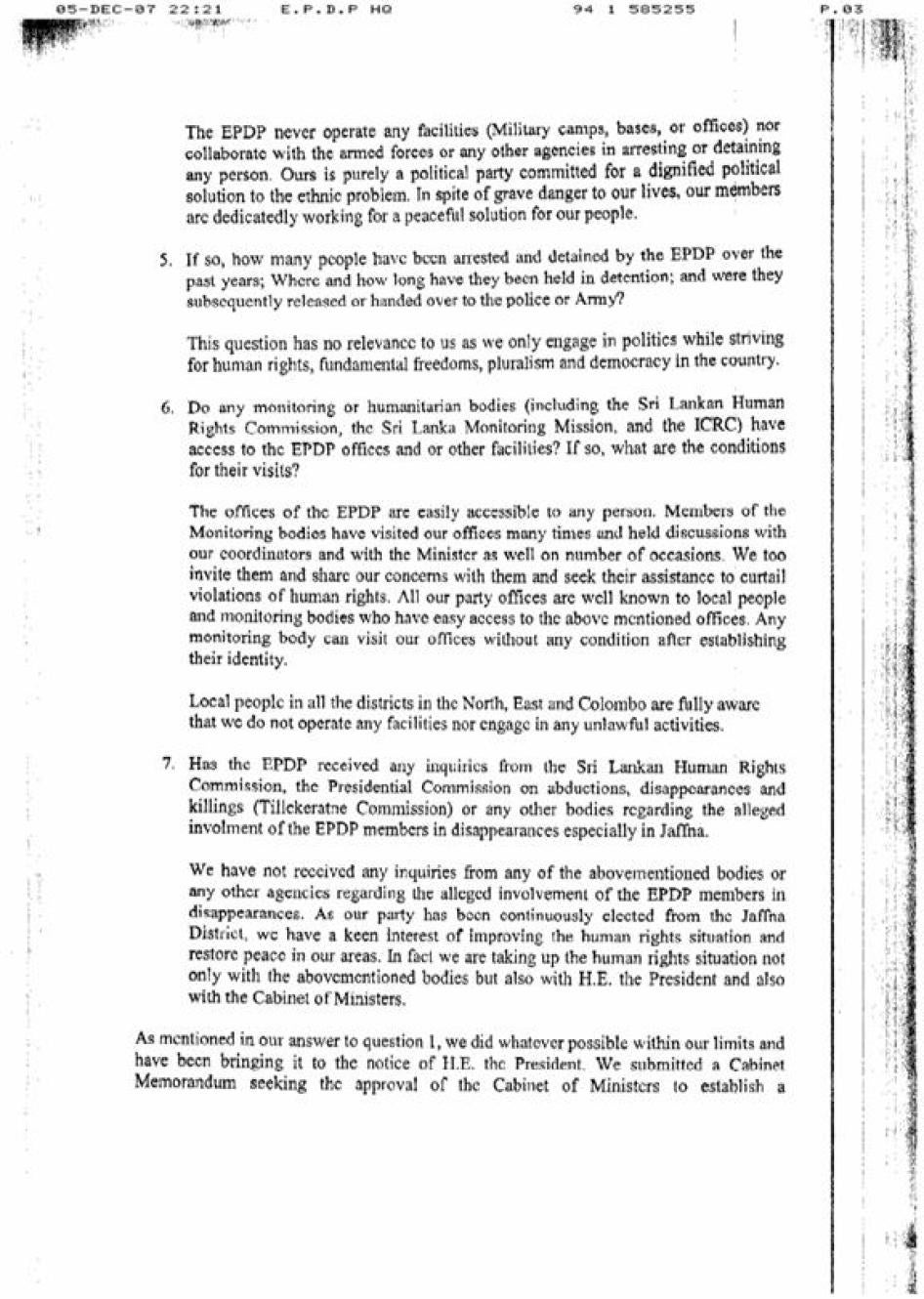

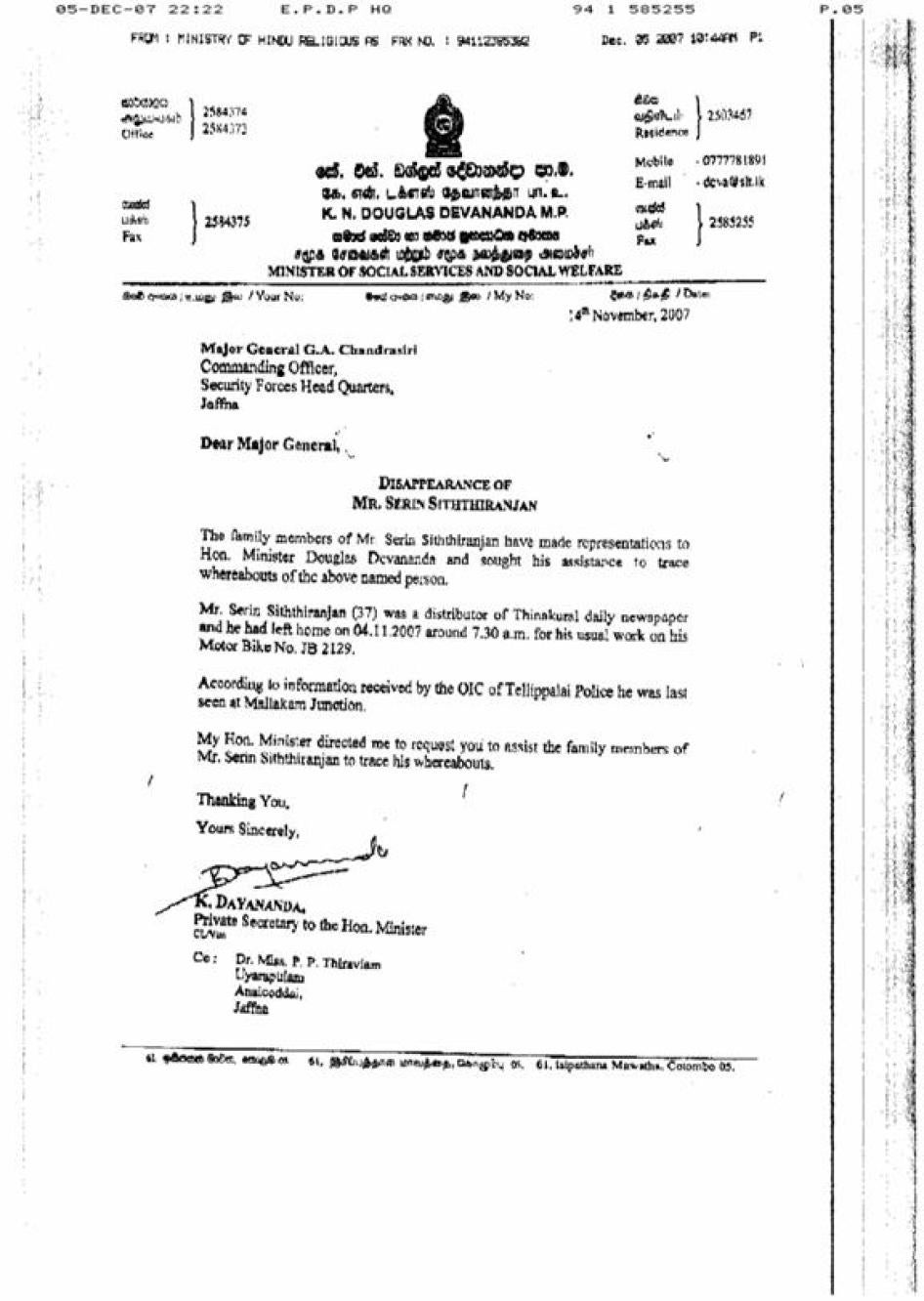

Human Rights Watch has raised its concerns in various meetings with the president of Sri Lanka, the foreign minister, and the minister for disaster management and human rights, among other Sri Lankan officials. Human Rights Watch sent inquiries to various Sri Lankan authorities-the Ministry for Disaster Management and Human Rights, the Inspectorate General of the Police, the Defense Ministry, the Human Rights Commission, and the Presidential Commission on Abductions, Disappearances, and Killings-requesting information related to the issues raised in this report. Human Rights Watch also sent an inquiry to Eelam People's Democratic Party (EPDP).

Human Rights Watch received responses from the Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka and the Sri Lankan police. The EPDP also responded to the inquiry. Their responses are incorporated in the relevant sections of this report. Other officials mentioned above did not respond to Human Rights Watch inquiries. Human Rights Watch letters of inquiry and responses we have received are appended to this report (Appendix II).

Appendix I of this report contains detailed descriptions of 99 cases of "disappearances" and abductions documented by Human Rights Watch. A list of 498 additional cases reported to Sri Lankan human rights groups is available at: http://hrw.org/reports/2008/srilanka0308/srilanka0308cases.pdf.

While all efforts were made to ensure that information in Appendix I is up to date, given the challenge of obtaining information from some parts of Sri Lanka, especially the north, it is possible that new developments may have occurred in some of the cases before the report went to print.

Human Rights Watch also notes that in some of the documented cases there were no eyewitnesses to the abduction or arrest, and such cases may not technically qualify as "disappearances." Most such cases were excluded from this publication; where we have included such cases it is because there is other evidence, set forth during our discussion of the case, suggesting the victim was abducted by a pro-government armed group, the LTTE, or government security forces.

II. Background

The armed conflict

In July 1983, an attack on government troops by the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) sparked riots in Colombo and elsewhere causing several hundred Tamil deaths, now referred to as Black July. The ensuing civil war between the government and the LTTE has been marked by gross violations of international human rights and humanitarian law by both sides, and has claimed over 60,000 lives.

The LTTE, in its struggle for an independent Tamil state, has been responsible for untold human rights abuses. It has repeatedly targeted civilians in its military operations, and assassinated leaders and members of rival Tamil parties, journalists, and human rights activists. The LTTE has engaged in massacres, retaliatory killings, and "ethnic cleansing" of Sinhalese and Muslim villagers. Since the late 1980s, the LTTE has controlled significant areas of north and east Sri Lanka, collecting "taxes" and administering justice. It has imprisoned, tortured, and executed thousands of Tamil dissidents and their family members. In areas under its control the LTTE tolerates no freedom of expression, association, or assembly, and it has recruited thousands of children for use as soldiers, many of whom have died in combat.

Government security forces have likewise been responsible for numerous serious violations throughout the two decades of fighting. The Sri Lankan armed forces have carried out massacres of Tamil civilians and engaged in indiscriminate aerial and artillery bombardment of populated areas, including medical facilities and places of worship where civilians have taken refuge. Suspected sympathizers with the LTTE and other Tamil groups have been subject to mass arrests, prolonged detention without trial, torture, enforced disappearances, and extrajudicial executions. Government forces have displaced hundreds of thousands of Tamil civilians, often in an apparent attempt to deprive the LTTE of local support.

For 20 years the civil war was punctuated by large-scale and bloody military operations, short-lived ceasefires, and the 32-month presence in the late 1980s of an Indian Peace Keeping Force. In February 2002, under the auspices of the Norwegian government, the Sri Lankan government and the LTTE signed a ceasefire agreement (CFA).[1] The ceasefire brought a respite from hostilities, but not an end to serious abuses.

From February 1, 2002, through December 31, 2006, the Nordic-led Sri Lanka Monitoring Mission (SLMM), established to monitor compliance with the CFA, reported over 4,000 violations of the agreement. These included targeted killings and other acts of violence and intimidation against civilians, committed predominately by the LTTE.[2]

While the Sri Lankan government did not formally withdraw from the CFA until January 2008, full-fledged fighting between the government forces and the LTTE resumed in mid-2006. The LTTE launched unsuccessful attacks against government-controlled Mutur and Jaffna, and attacked Sri Lankan military bases and convoys in different parts of the country-from Palaly airbase in the north to Navy headquarters in southernmost Galle.

In 2006 through early 2007, the government concentrated its military offensive in the east, which was already considerably weakened after the cadre of the LTTE chief military commander there, V. Muralitharan (aka Colonel Karuna), split from the LTTE in March 2004 and began cooperating with government forces. Following large-scale military operations in the Trincomalee, Batticaloa, and Vakarai areas, the government claimed in March 2007 to have cleared the LTTE from the eastern coast.

The fighting is likely to continue. For the past 18 months, both parties have treated the ceasefire agreement as defunct, and the government, inspired by its military successes in the east, has made no secret of its intentions to proceed with a military offensive in the north. Clashes in the northern districts of Mannar and Vavuniya in the second half of 2007 have already inflicted heavy casualties on both sides.

The resumption of major military operations also triggered a new cycle of human rights abuses, including intentional and indiscriminate attacks on civilians, forced returns of internally displaced people, extrajudicial executions and "disappearances," arbitrary arrests under draconian emergency laws, and recruitment of children as soldiers. The renewed conflict has also led to renewed government crackdown on dissenting voices, including political opponents, journalists, and human rights activists.[3]

History of "disappearances" in Sri Lanka

The large-scale enforced disappearances are not a new phenomenon in Sri Lanka. In the past, thousands of people have "disappeared" in the context of the two major civil conflicts that have wracked the country since independence: the insurgency led by the left-wing Sinhalese Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) in 1987-90, and the two-decade long armed conflict between the LTTE and the government.

Presidential commissions established during the 1990s found that over 20,000 persons "disappeared" during these two conflicts. Some analysts and domestic human rights groups believe that the actual figure may be two to three times higher.[4]

Between 1983 and mid-1987, Amnesty International documented at least 680 cases of "disappearances" committed in the north and east in the context of the escalating armed conflict between the security forces and militant Tamil groups.[5] Another 43 cases were reported to the organization from mid-1987 to 1989, when the Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF) was responsible for security in the north under the terms of the Indo-Sri Lanka Accord.[6]

In the south, from 1987 to 1989, the security forces "disappeared" and extrajudicially executed thousands of people while suppressing an armed insurgency within the majority Sinhalese community.[7] Many of these abuses were perpetrated by plainclothes death squads which also regularly displayed mutilated bodies of the executed insurgents and their supporters in public.[8]

This brutal counter-insurgency campaign was then transferred to the east when the military returned there after the resumption of hostilities between the government and the LTTE in June 1990. The number of those reported to have been "disappeared" or deliberately killed in the custody of the Sri Lankan security forces reached thousands within months. The majority of victims were young Tamil men suspected of belonging to or associating withthe LTTE. Most of them "disappeared" after being detained in the course of cordon‑and‑search operations conducted by the army, often in conjunction with the police, and particularly the elite Special Task Force (STF).[9]

A new wave of "disappearances" engulfed the north in 1996-1997 after the army succeeded in regaining control of the Jaffna peninsula from the LTTE as a result of several large-scale military operations. The UN Working Group on Enforced and Involuntary Disappearances received reports of 622 new cases in 1996, and another 92 in 1997-the highest number of "disappearances" reported from any country in those years.[10] Most of the victims "disappeared" after they were taken into custody during round-up operations or at military checkpoints set up throughout the peninsula.[11]

In response to international criticism and public pressure, in the 1990s, successive Sri Lankan presidents set up commissions to investigate the countless "disappearances."

The first Presidential Commission of Inquiry into the Involuntary Removal of Persons, set up by President Ranasinghe Premadasa in January 1991, was a specious exercise. Its mandate did not even cover the entire period of the JVP uprising when thousands of "disappearances" took place.[12]

In 1994 President ChandrikaKumaratunga set up three linked commissions of inquiry, each named a "Presidential Commission of Inquiry into Involuntary Removal or Disappearance of Persons," to investigate abuses that occurred in different regions of the country from 1988 to 1994. The commissions began their work in January 1995.

Each commission, composed of three members, was assigned a specific geographical area of the country. After the commissions' mandate expired, the government appointed a fourth commission of inquiry, known as the "All Island Presidential Commission on Disappearances," to inquire into some 10,000 remaining complaints. This commission functioned from 1998 to 2000.

The four commissions analyzed tens of thousands of complaints and established that over 20,000 cases of "disappearances" had occurred, most at the hands of security forces.[13]

Upon completion of its work, the All Island Commission referred 16,305 complaints which it could not review (due to the limitations of its mandate) to the Sri Lankan Human Rights Commission. In 1994 the HRC started processing these complaints, and the commission's Disappearances Data Base Project eventually identified 2,127 cases to be further investigated by the commission. In July 2006, however, the HRC reportedly decided not to pursue the investigations into these complaints "unless special directions are received from the Government."[14]

Uncovering evidence of systematic state-sponsored violence, the three regional commissions identified suspected perpetrators in 1,681 cases, and the All Island Commission identified another several hundred individuals responsible for "disappearances."[15]

These findings, however, led to few prosecutions and only a handful of convictions. According to the government, following the commissions' recommendations, in 1997 a special "Disappearances Investigations Unit" was established under the deputy inspector general of the police, which by the end of 2000 had completed investigations into 1,175 of the 1,681 cases identified by the commissions. These cases were then transferred to the newly established "Missing Persons Commissions Unit" in the Attorney General's Department to consider instituting criminal proceedings against the perpetrators. As a result, criminal proceedings were instituted against 597 members of the security forces.[16] Very few of those cases, however, seem to have proceeded to trial, and only a few junior officers were convicted.[17]

While no independent commission was established to look into the "disappearances" committed in Jaffna in 1996, the Sri Lankan secretary of defense created a special Board of Investigation consisting of high-level officials of the armed forces and the police to examine these cases. Having investigated 2,621 complaints, the Board of Investigation concluded that378persons had "disappeared" in the Jaffna peninsula in 1996. It is unclear whether any members of the security forces were ever indicted based on the Board of Investigation's findings-according to the government, the Disappearances Investigation Unit had not completed any investigations into these cases by the end of 2002;[18] more recent information on these investigations is not available.

The only two noteworthy cases where the investigations into "disappearances" have led to prosecutions and convictions are the Embilipitiya killings and the murder of Krishanthi Kumaraswamy, described immediately below.

Following years of investigation into the 1989 abduction, torture, and murder of more than 50 high-school students in an army camp in Embilipitiya, nine suspects were brought to trial in 1994. In February 1999, five military personnel, including the local brigadier, as well as the principal of the high school, were convicted of abduction with the intent to commit murder and wrongful confinement and sentenced to 10 years in prison.[19] The brigadier was later acquitted on appeal for lack of direct involvement.

In the other case, nine soldiers were arrested for the 1996 abduction and murder of an 18-year-old Tamil student, Krishanthi Kumaraswamy, and her mother, brother, and a friend in Jaffna. In 1998 five of the soldiers were convicted and sentenced to death.

The five convicted soldiers revealed the existence of mass graves in the town of Chemmani, which allegedly contained the bodies of up to 400 persons "disappeared" and killed by security forces in 1996, when government troops recaptured the Jaffna peninsula from the LTTE.[20] Subsequent investigations initially fed hopes that this would be a first significant step toward ending impunity for "disappearances." Ultimately, however, only 15 bodies were discovered because of "unfinished exhumations, inconclusive DNA tests, and political resistance."[21] Initial arrests of several members of the security forces led to no indictments, and by early 2006 the investigation had come to a standstill.[22]

As the above description makes clear, the work of the various commissions of inquiry and the investigative bodies ultimately failed to bring about a meaningful accountability process.

The commissions did make detailed recommendations for legal and institutional reforms to prevent "disappearances" in the future. Most of these, however, were either completely ignored by successive governments, or were introduced only on paper, with no genuine effort made to implement them.[23] For example, the commissions determined that the Emergency Regulations created a legal framework conducive to "disappearances," and called for "the utilization of the powers under the Emergency Regulations [to] be minimized."[24] However, as this report shows, the current government has continued to rely heavily on emergency laws, which remove basic constitutional safeguards and grant sweeping powers to the security forces.

One important step taken by the Kumaratunga administration in pursuance of the commissions' recommendations was the simplification of the system for paying compensation and issuing death certificates to the families of the "disappeared." On the basis of new legislation, some 15,000 death certificates were issued between 1995 and 1999,[25] and by 2002, compensation had been paid to families of 16,324 victims.[26]

However, the 2006 decision of the HRC to drop the investigation into the 2,127 complaints of "disappearances" in its database was reportedly due to HRC concerns that "the findings will result in payment of compensation" to the families, suggesting that the one area in which progress was being made-compensation-actually may have led to the curtailment of essential investigations. The decision also casts doubt on the extent to which the government would be willing to pay compensation in the future.[27]

In the 1990s the large-scale pattern of "disappearances" in Sri Lanka was repeatedly addressed by the UN Working Group on Enforced and Involuntary Disappearances. The UN Working Group undertook field missions to the country in 1991, 1992, and 1999. Between 1980, when the UN Working Group was established, and 2006, the Working Group transmitted 12,319 cases to the government-of those, 5,749 cases remain outstanding.[28]

Following its visits to Sri Lanka, the UN Working Group made a number of recommendations to the government for the prevention and proper investigation of "disappearances." However, many key recommendations have not been implemented. For example, the Prevention of Terrorism Act and the Emergency Regulations have not been abolished or brought into line with internationally accepted human rights standards; the central register of detainees has not been set up; and enforced disappearance has not been made an independent offence under the criminal law. Nor did the government, as urged by the UN Working Group, establish an independent body with power to investigate all cases of "disappearance" since 1995, or accelerate its efforts to bring the perpetrators to justice.

During its visit to Sri Lanka in 1999, the UN Working Group expressed its serious concern about the lack of progress in investigations and prosecutions, and the government's failure to implement many of the Working Group's recommendations.[29] The failure of successive Sri Lankan governments to seriously consider and implement the recommendations of the national commissions of inquiry and the UN Working Group has considerably contributed to the current crisis.

III. Legal Framework

Sri Lanka's obligations under international law

Sri Lanka is party to the major international human rights treaties, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR)[30] and the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment.[31]

Sri Lanka is also obliged to abide by international humanitarian law (the laws of war), which regulates the conduct of hostilities and protects persons affected by armed conflict, including civilians and captured combatants. The hostilities between the Sri Lankan government and the LTTE meet the criteria of a non-international armed conflict under the 1949 Geneva Conventions, and Sri Lanka and the LTTE thus are required to adhere to Common Article 3 of the 1949 Geneva Conventions which applies to internal armed conflict and customary international humanitarian law.[32]

In addition, Sri Lanka should follow the standards set out in the 1992 UN General Assembly's Declaration on the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearances (the "Declaration on Enforced Disappearances").[33] Although a non-binding standard, the Declaration reflects the consensus of the international community against this type of human rights violation and provides authoritative guidance as to the safeguards that must be implemented in order to prevent it.

The prohibition against enforced disappearances has recently been reinforced by the adoption of the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance (Convention against Enforced Disappearances).[34] This multinational treaty was open for signature on February 6, 2007, and at the time of writing, 71 countries had signed the convention.[35]Sri Lanka has not signed the Convention.

Since 1984 the Sri Lankan government has repeatedly declared a state of emergency in the country. Under the ICCPR, states are allowed to suspend temporarily (or derogate from) certain provisions during an officially proclaimed "public emergency which threatens the life of the nation," but only to the extent strictly necessary under the circumstances.[36] However, certain rights, including the right to life and protection from torture, are consider non–derogable and thus can never be suspended.[37] The Declaration on Enforced Disappearances unequivocally states that "no circumstances whatsoever, whether a threat of war, a state of war, internal political instability or any other public emergency, may be invoked to justify enforced disappearances."[38]

Prohibition of enforced disappearances

The UN Declaration on Enforced Disappearances describes "disappeared" persons as those who are "arrested, detained, or abducted against their will or otherwise deprived of liberty by government officials, or by organized groups or private individuals acting on behalf of, or with the direct or indirect support, consent, or acquiescence of the government, followed by a refusal to disclose the fate or whereabouts of the persons concerned or by a refusal to acknowledge the deprivation of their liberty, which places such persons outside the protection of the law."[39]

Enforced disappearances constitute "a multiple human rights violation."[40] They violate the right to life, the prohibition on torture and cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment, the right to liberty and security of the person, and the right to a fair and public trial. These rights are set out in the ICCPR and the Convention against Torture.[41]

The UN Declaration on Enforced Disappearances recognizes the practice of "disappearance" as a violation of the rights to due process, to liberty and security of a person, and to freedom from torture. It also contains a number of provisions aimed at preventing "disappearances," stipulating that detainees must be held in officially recognized places of detention, of which their families must be promptly informed; that they must have access to a lawyer; and that each detention facility must maintain an official up-to-date register of all persons deprived of their liberty.[42]

International humanitarian law also provides protection against enforced disappearances by prohibiting acts that precede or follow a "disappearance." Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions requires that persons taken into custody, whether civilians or captured combatants, be treated humanely in all circumstances. Such persons may never be subjected to murder, mutilation, cruel treatment or torture, or the passing of sentences and carrying out of executions, without a proper trial by a regularly constituted court.[43] Enforced disappearances are considered a violation of customary international humanitarian law.[44]

An enforced disappearance committed as part of a widespread or systematic practice constitutes a crime against humanity, a term that refers to acts which, by their scale or nature, outrage the conscience of humankind. This has been recognized under the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, the Declaration on Enforced Disappearances, and the Convention against Enforced Disappearances.[45]

Abductions perpetrated by the LTTE, which are often followed by summary executions, would also qualify as enforced disappearances under international human rights law if carried out in the areas where the LTTE has effective control and acts as de facto government authority. While in government-controlled areas these LTTE crimes would not technically qualify as "disappearances," this should not lead to any confusion about their nature; abductions are serious human rights abuses and violate the LTTE's obligations under international humanitarian law, specifically Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions.

Duty to investigate and to establish accountability

Under international law, Sri Lanka has a duty to investigate serious violations of human rights and to punish the perpetrators.[46] States are obliged to ensure that enforced disappearances are considered crimes by law, and to prosecute any person who commits, orders, attempts to commit, or otherwise participates in an enforced disappearance, or has responsibility as a superior.[47]

The Declaration on Enforced Disappearances emphasizes that it is the state's obligation to ensure that persons having knowledge of an enforced disappearance have the right "to complain to a competent and independent State authority and to have that complaint promptly, thoroughly and impartially investigated by that authority." Even in the absence of a formal complaint, the state should promptly refer the matter to the appropriate authority for investigation whenever there are reasonable grounds to believe that an enforced disappearance has been committed. When the facts disclosed by an official investigation so warrant, any person alleged to have perpetrated an act of enforced disappearance is to be brought before competent civil authorities for the purpose of prosecution and trial.[48]

International law considers a "disappearance" to be a continuing offense so long as the state continues to conceal the fate or the whereabouts of the "disappeared" person. The perpetrators of "disappearances" should not benefit from any special amnesty or other measures that might exempt them from a criminal proceeding or sanction.[49]

The Convention against Enforced Disappearances calls on states to investigate abductions and other acts that fall into the definition of a "disappearance" committed by non-state actors and to bring those responsible to justice.[50]

In cases where "complaints by relatives or other reliable reports" suggest that a "disappearance" has resulted in the unnatural death of the individual in state custody, Sri Lankan authorities-in accordance with the UN Principles on the Effective Prevention and Investigation of Extra-legal, Arbitrary and Summary Executions-should launch a thorough, prompt, and impartial investigation to "determine the cause, manner and time of death, the person responsible, and any pattern or practice which may have brought about that death." The investigation should result in a publicly available written report.[51]

In its resolutions, the UN General Assembly has repeatedly called on governments to devote appropriate resources to searching for the "disappeared" and to "undertake speedy and impartial investigations."[52] It has urged states to ensure that law enforcement and security authorities are fully accountable in the discharge of their duties, and emphasized that such accountability must include "legal responsibility for unjustifiable excesses which might lead to enforced or involuntary disappearances and to other violations of human rights."[53]

Redress for victims

Under international human rights law, Sri Lanka is obliged to provide reparations to victims of serious human rights violations. The ICCPR requires states to provide an "effective remedy" for violations of rights and freedoms and to enforce such remedies.[54] The UN Human Rights Committee has noted that "reparation can involve restitution, rehabilitation and measures of satisfaction, such as public apologies, public memorials, guarantees of non-repetition and changes in relevant laws and practices, as well as bringing to justice the perpetrators of human rights violations."[55]

Guidance on reparation to victims can be found in the Basic Principles and Guidelines on the Right to a Remedy and Reparation for Victims of Gross Violations of International Human Rights Law and Serious Violations of International Humanitarian Law. The Principles reaffirm that a state should provide adequate, effective, and prompt reparation to victims for acts or omissions constituting violations of international human rights and humanitarian law norms.[56]

The right to reparation is of particular importance as a way of establishing truth and responsibility in the case of enforced disappearances, which are "continuing human rights violations committed with the very intention of evading responsibility, truth and legal remedies."[57]

The Declaration and the Convention against Enforced Disappearances specifically reaffirm the right of victims-defined in the Convention as "any individual" who has suffered harm as the direct result of an enforced disappearance-to obtain reparation and compensation in the form of material and moral damages as well as restitution, rehabilitation, satisfaction, including restoration of dignity and reputation, and guarantees of non-repetition.[58]

The Convention against Enforced Disappearances also establishes the responsibility of the state to "take all appropriate measures to search for, locate and release disappeared persons and, in the event of death, to locate, respect and return their remains," and recognizes the right of victims "to know the truth"-regarding the circumstances of the enforced disappearance, the progress and results of the investigation, and the fate of the disappeared person.[59] This right was reaffirmed in a 2005 resolution by the UN Commission on Human Rights.[60]

Sri Lankan national law

In line with international standards, Sri Lanka's constitution guarantees fundamental human rights, including the right to life, liberty, and security of person, the right to a fair trial, and the prohibition against torture. However, emergency rule has been in place with only short intervals of constitutional rule since 1971, and these guarantees have been superseded by emergency laws and regulations.

National and international legal experts have repeatedly criticized the Public Security Ordinance (PSO) of 1947 and emergency laws enacted by various Sri Lankan governments in pursuance of powers granted by the ordinance.[61] These laws not only contradict international standards and undermine the rights enshrined in Sri Lanka's constitution,[62] but essentially create a legal framework conducive to a wide range of human rights violations, including enforced disappearances.[63]

The two Emergency Regulations currently in force-the Miscellaneous Provisions and Powers of August 2005 and the Prevention and Prohibition of Terrorism and Specified Terrorist Activities of December 2006-are no exception in this respect.

Human Rights Watch's 2007 report on the conflict in Sri Lanka, Return to War, provides a detailed analysis of these regulations, which grant security forces sweeping powers of arrest and detention, unnecessarily restrict freedom of movement, criminalize a range of peaceful activities protected under Sri Lankan and international law, and introduced a wide immunity clause shielding members of the security forces from criminal prosecution.[64]

Several provisions of the Emergency Regulations are of particular concern in relation to the issue of enforced disappearances. In its June 2007 report, the International Crisis Group noted that "arrests under the Emergency Regulations are sometimes hard to distinguish from enforceddisappearances, as when non-uniformed government agents arrest people without announcing under whatauthority they are acting, the reason for the arrest or where the arrested person is being taken."[65]

Indeed, the 2005 Emergency Regulations enable security forces to arrest without a warrant any person "acting in any manner prejudicial to the national security or to the maintenance of public order, or to the maintenance of essential services." The term "prejudicial to the national security" is not further defined.[66]

The detention period following arrest under the regulations is limited to 90 days, yet in practice suspects may be detained indefinitely, as the police can get remands from magistrates and keep the detainees in custody without bail. In addition, the defense secretary can issue "preventive detention" orders to hold suspects for up to one year-no evidence is required, so long as the secretary is "of the opinion" that a preventive detention order is needed.[67]

Another key factor directly contributing to widespread "disappearances" is the lack of public information on detention facilities, which facilitates secret detention and prevents monitoring. The 2005 Emergency Regulations do not require officials to publish a list of authorized places of detention, in violation of international standards.[68]

The absence of this legal requirement in effect negates the ability of the Human Rights Commission to monitor the detention facilities. The Human Rights Commission Act requires the commission to be notified of every arrest and detention, but according to nongovernmental organizations and the UN Working Group, in practice, this requirement has been routinely ignored.[69]

The problem of secret detention is exacerbated by the fact that under the emergency laws, arrest and detention can be carried out by police, the armed forces (army, navy, or air force), or jointly. Given that security forces have conducted operations with non-state armed groups (see below), it is often impossible to establish which unit was responsible for the arrest and to which detention facility the individual apprehended was taken. This recreates the conditions under which widespread abuses went unchecked in the 1990s when, according to one report on Sri Lanka's counterterrorism legislation, "disappearances became normal, because nobody knows who the arresting person is and where the victim is taken to."[70]

In a number of cases documented by Human Rights Watch, family members of the "disappeared" stated that in response to their inquiries, the army and the police kept referring them from one to the other, each refusing to acknowledge responsibility for the arrests. In a June 2007 letter, Human Rights Watch asked the Sri Lankan government how many people it had arrested under the 2005 Emergency Regulations and where they were being held. The government did not provide a response, saying that these figures were being tabulated by the police.[71] In November 2007, Human Rights Watch again asked the Sri Lankan police to provide statistics on the number of people detained under the two Emergency Regulations, charges brought against them, the number of cases that proceeded to trial, and the number of people released following the arrest. In a January 2, 2008, response to Human Rights Watch the national police repeated that "response will be submitted once statistics are compiled."[72]

The delegation of broad powers of arrest and detention to the military-by the Emergency Regulations and by an April 2007 presidential "notification" issued pursuant to the terms of the Public Security Ordinance-raises serious concerns.[73] Sri Lankan lawyers and human rights organizations as well as international groups have warned that in the country's recent past, the granting of policing powers to the military led to widespread abuses, including torture and "disappearances."[74]

The 2005 Emergency Regulations also re-introduced provisions allowing the disposal of dead bodies without public notification.[75] In clear derogation from the procedures on inquests into deaths specified in the Sri Lankan Code of Criminal Procedure, the regulations give wide discretion to the deputy inspector general of the police to decide when an inquiry into a death caused by security forces takes place, and to dispose of bodies without disclosing the results of the post-mortem examination.[76] These provisions effectively prevent proper investigations into custodial deaths and shield security forces from accountability for torture, disappearances, and extrajudicial executions.[77]

Further obstacles to accountability are created by the immunity clause contained in the Emergency Regulations (Prevention and Prohibition of Terrorism and Specified Terrorist Activities) of 2006. Regulation 19 prohibits legal proceedings against a government official who commits a wrongful act while implementing the regulations-as long as he or she acted "in good faith and in the discharge of his official duties."

The 2006 Emergency Regulations give security forces a wide range of powers and leave victims of violations with virtually no opportunity for redress. Sri Lankan NGOs have noted that in the absence of independent review and given the notorious history of abuse and lack of accountability of security forces, this regulation "could easily become one that promotes impunity rather than providing for immunity for bona fide actions."[78]

The Emergency Regulations contain several provisions that in principle are intended to prevent abuses, including the risk of "disappearances." Persons arrested shall be turned over to the police within 24 hours and their family provided with an "arrest receipt" acknowledging custody.

However exceptions undermine the scope of these protections. Rather than 24 hours, Regulation 68 allows a member of the armed forces, authorized by his commander, to keep a person in custody for up to seven days at a time for the purpose of questioning or for any matter connected to such questioning.[79]

The requirement to issue an "arrest receipt" does not apply to cases of preventive detention or arrests carried out by those authorized directly by the president.[80] Failure to provide a receipt, or to explain why it was impossible to provide one, is punishable by fine and imprisonment. However, there is no indication that any members of the security forces have ever been charged with or prosecuted for this offense.[81] Notably, in his response to Human Rights Watch's inquiry, the national police stated that if the police officers fail to issue receipts they are "liable for disciplinary action." The police did not specify what such disciplinary action could involve, but claimed that no instances of the police's failure to issue an arrest receipt "have been reported so far."[82]

Presidential directives to the security forces initially published in July 2006 and re-circulated in April 2007 instruct the security forces to respect basic human rights, including by providing information on the reasons for arrest, identifying themselves while carrying out the arrests, and allowing the arrested persons to inform the family members of their whereabouts. The directives also instruct the security forces to inform the Human Rights Commission within 48 hours of any arrest and allow the commission unimpeded access to all detainees.[83]

However, these directives remain largely declarations on paper-with no legal force and no penalties for non-compliance. Research conducted by Human Rights Watch and other organizations demonstrates that the security forces routinely ignore the instructions and face no consequences for doing so.[84]

In many of the cases documented in the Appendix to this report, police or army personnel conducting unlawful arrests that led to "disappearances" failed to introduce themselves or provide the families with any information regarding the whereabouts of the detainees. An HRC representative also told Human Rights Watch that it is always family members or human rights groups who inform his office about such "arrests" rather than the security forces themselves.[85]

IV. Perpetrators and Victims

The phenomenon of enforced disappearances that has haunted Sri Lanka since the 1980s has now returned. With the resumption of major military operations between government forces and the LTTE, a new wave of enforced disappearances and abductions engulfed the country in 2006-2007. With the end of the ceasefire, it is likely to accelerate.

While the exact number of "disappearances" perpetrated over the last two years remains unknown, data from local organizations and the UN Working Group, as well as information collected by Human Rights Watch, suggests that the problem has reached crisis proportions.

In 2006 the UN Working Group transmitted more cases of "disappearances" as urgent appeals to the Sri Lankan government than to any other country in the world. At the conclusion of its session in March 2007, the UN Working Group again expressed "deep concern that the majority of new urgent action cases are regarding alleged disappearances in Sri Lanka."[86]

Judging by various figures on "disappearances" released by government and nongovernmental sources, more than 1,500 people have been reported missing from December 2005 through December 2007, and the majority of them are still unaccounted for.

On June 28, 2007, the chairman of the Presidential Commission on abductions, disappearances, and killings, Judge Tillekeratne, told the media that 2,020 abductions and "disappearances" were reported to his commission between September 14, 2006, and February 25, 2007 (1,713 cases of "disappearances" and 307 abductions). According to Tillekeratne, 1,134 persons were later "found alive and reunited with their famlies," but the fate of the rest remains unknown.[87]

Although Judge Tillekeratne presented the figures as proof that the majority of the "disappeared" had returned to their homes, it shows in fact that at least 886 people "disappeared" without a trace in less than 12 months.

The national Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka does not publicize its data on cases submitted to its review. According to credible sources interviewed by Human Rights Watch, as well as press reports, the commission recorded about 1,000 cases in 2006 and over 300 cases in the first four months of 2007.[88] The commission refused to provide any data in response to Human Rights Watch's letter of inquiry.[89]

On October 31, 2007, a credible Sri Lankan NGO, the Law and Society Trust, in collaboration with four local partners, including the Civil Monitoring Commission[90] and the Free Media Movement, submitted the details of 540 alleged "disappearances" perpetrated between January and August 2007 to the Presidential Commission of Inquiry (CoI).[91]

While "disappearances" have occurred all over the country, certain regions have been particularly affected.

The majority of cases are reported from the Jaffna peninsula-according to HRC figures published in the media, at least 835 persons were "disappeared" or abducted there between December 2005 and May 2007.[92] A respected Sri Lankan group, University Teachers for Human Rights (Jaffna), reported in December 2007 that out of 948 individuals reported missing in Jaffna from December 2005 to October 2007, 684 remain unaccounted for.[93]

Since late 2006, "disappearances" and abductions have also become a widespread practice in Colombo, as well as in the districts of Mannar, Batticaloa, Ampara, and Vavuniya. Out of 540 cases submitted to the CoI by the Law and Society Trust, 271 were from Jaffna, 78 from Colombo, 40 from Mannar, 39 from Batticaloa, 15 from Ampara, and 14 from Vavuniya.[94]

Since its formation in November 2006, the Civil Monitoring Commission (CMC) has recorded details of dozens of cases of "disappearances" and abductions in Colombo, at the same time acknowledging that this reflects only a fraction of the total.[95]

Human Rights Watch's research in Sri Lanka in February, March, and June 2007, examined in detail 99 cases out of the hundreds of people believed to have been "disappeared" or abducted in 2006 and 2007. These include cases from Colombo, Jaffna, Vavuniya, Mannar, Tricomalee, and Batticaloa.

While the government claims that the number of "disappearances" and abductions has dropped dramatically since June 2007, available evidence shows a high number of new "disappearances."

In August 2007, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) stated it had received reports on 34 abductions in three weeks,[96] and the HRC recorded 21 "disappearances" in Jaffna alone.[97] Weekly reports published by the Sri Lanka Monitoring Mission (SLMM) suggest that in September and October 2007 abductions in the east continued almost on a daily basis, and, for example, in the week of December 3 – December 9, 2007, 22 abductions were reported to the SLMM in the east.[98] The Law and Society Trust report also shows that the number of reported "disappearances," which had been gradually decreasing in April-July 2007, rose sharply again in August.[99]

Perpetrators

"Disappearances" by their nature are abuses perpetrated with the very intention of evading responsibility. In conflicts throughout the world the perpetrators often try to conceal their identity and ensure that there are no direct witnesses. This makes establishing accountability challenging and allows the parties to a conflict to blame the abuses on each other. Sri Lanka is no exception in this respect.

The Sri Lankan government routinely denies the responsibility of its security forces for "disappearances" and dismisses the allegations of eyewitnesses as unreliable because they cannot point indubitably to the identity of the perpetrators. In a number of cases documented by Human Rights Watch and others, eyewitnesses were unable to clearly identify the perpetrators, describing them as a "group of armed men" arriving in a "white van," on motorcycles, or on foot.[100]

However, in the majority of cases documented, there is sufficient evidence to suggest the involvement or complicity of the Sri Lankan security forces-army, navy, or police-in the "disappearances."

Witnesses in some cases also pointed to members of pro-government non-state armed groups, acting either in conjunction with the security forces or independently, as the perpetrators. These are Tamil groups that are in conflict with the LTTE-and whose members have frequently been targets of LTTE attack-specifically the Karuna group in the east and Colombo, and the EPDP in the northern Jaffna peninsula.

In its first submission to the CoI in August 2007, the Law and Society Trust noted that out of the 396 cases of alleged "disappearances," 352 were perpetrated by "government agents," and in 44 cases the perpetrators were unknown.[101]

Undoubtedly, the LTTE is also responsible for "disappearances" and abductions. The numbers are comparatively low, however, in part because "disappearance" is not a prime tactic of the LTTE and in part because cases may be underreported due to the fear instilled in victim's families and eyewitnesses.

Sri Lankan armed forces

In the absence of a significant external defense mission throughout Sri Lanka's modern history, the armed forces have primarily focused on internal security and counter-insurgency warfare.

During the country's internal conflicts, the government has frequently applied laws conferring additional powers on the armed forces. Since 2001, successive Sri Lankan presidents have invoked the powers under section 12 of the Public Security Ordinance (PSO), allowing them to heavily rely on the armed forces "when public security is endangered and the President is of the opinion that the police are inadequate to maintain public order."[102]

The powers granted to the military under the PSO are limited to standard search and arrest procedures; dispersal of unlawful assemblies; seizure and removal of offensive weapons and substances from unauthorized persons in public places; seizure and removal of guns and explosives (when written authority is granted by the president or an authorized person). Section 12 also specifically prohibits the armed forces from exercising powers under Chapter XI of the Code of Criminal Procedure Act, such as investigating crimes and bringing suspects before magistrates.

The 2005 Emergency Regulations, however, go far beyond the PSO; Regulation 52 confers broad policing powers onto officers of the armed forces, when so authorized by the respective commander.[103] Under Regulation 68, members of the armed forces, when authorized by the respective commander, can question any person in custody, and hold him in the custody of the authorized member of the armed forces for a period not exceeding seven days at a time for the purpose of questioning, or for any matter connected to such questioning.[104]

Commenting on the regulations granting broad policing powers to the armed forces, a prominent Sri Lankan lawyer noted that this is "an exercise fraught with danger" as the military forces "lack the proper training, experience and investigative skills to engage in such an exercise, and considering the nature of the training they undergo and the experiences of the battlefield, their psychological make-up may not be conducive to the conducting of an effective investigation within the confines of the law."[105]

The involvement of the army and navy in "disappearances" is particularly evident in the Jaffna peninsula. [106] Historically, much of the heaviest fighting between the LTTE and the Sri Lankan armed forces has occurred on the peninsula, evident in the war-torn appearance of its major town, Jaffna. The peninsula is dotted with a number of Sri Lankan military bases-land, naval, and air-whose presence often is a factor in "disappearance" cases. In 21 out of 37 cases of "disappearances" documented by Human Rights Watch in Jaffna, evidence strongly suggests that the perpetrators were members of the armed forces. In some cases, individuals "disappeared" after being detained during large-scale cordon-and-search operations. In such cases, family members knew exactly to which military camps their relatives were taken, and sometimes even wrote down the license plate numbers of the military vehicles that took them away.

For example, in one of the cases documented by Human Rights Watch, two women witnessed the arrests of their husbands on December 8, 2006, after the men came to retrieve their IDs seized during cordon-and-search operations by the military in Navindil. The women managed to write down the license plate numbers of the vehicles that took their husbands away (40041-14 and 40032-14) and later saw the vehicles at the Point Pedro military camp where they went looking for their husbands. Despite these details, the military denied ever arresting the men and at the time of writing their fate remains unknown.[107]

In other cases, the families' suspicion of the military involvement in "disappearances" was reinforced by subsequent inquiries in army camps. For example, after 26-year-old Thavaruban Kanapathipillai and 30-year-old Shangar Santhivarseharam went missing on August 16, 2006, on the way to Kachai in eastern Jaffna district, their families made inquiries with the Kodikamam military camp located near their place of residence. While the military denied having detained the men, the relatives saw Kanapathipillai's bicycle-that the two men rode on the day of their "disappearance"-parked near the camp, in the area controlled by the military. The camp commander eventually returned the bicycle to the relatives, yet denied having any knowledge of the men's fate.[108]