When my colleague and I sat down last April with Hamid, an Iraqi man from Baghdad, his trauma-induced stutter said as much as the words he spoke. Huddled inconspicuously in a dingy restaurant, Hamid recounted how militia members killed his partner along with three other men, two kidnapped from their Baghdad homes, two slaughtered in the streets. The next day, Hamid said, "they came for me. They came into my house and they saw my mother, and one of them said, 'Where's your faggot son?' My mother called me after they left, in tears. ... I can't go home."

As the world hails Iraq's supposed return to normality, the country's militias -- the same ones that spent years waging a sectarian civil war -- have found a new, less apparent target: men suspected of being gay. The systematic killings, which began earlier this year, reveal the cracks behind Iraq's fragile calm. Iraq's leaders may talk of security and democracy from behind barbed wire in the Green Zone, but the surge of murders against gay men is a stark sign of how far Iraqi society still has to go.

During a 10-day Human Rights Watch research trip to Iraq in April, we heard harrowing stories of torture, abductions, kidnappings, extortion, and murder. We listened to dozens of men who had faced violence at the hands of armed militias, attacked by youths with guns for violating the unwritten codes of Iraqi masculinity. A number of signs might implicate one as being not "manly" enough, from neighborhood gossip that a man is gay to looking somehow effeminate or foreign in the wrong people's eyes: wearing one's hair too long or one's jeans too tight, for example. There is no count available for the number of deaths since the killings began earlier this year, but one U.N. worker told us that the victims could number in the hundreds.

Not a single murder has been adequately investigated, and not a single murderer has been arrested. Infiltrated by militias and fearing for their reputations if they defend "immorality," government officials turn a blind eye.

Most survivors pointed to Moqtada al-Sadr's Mahdi Army militia as the main culprit in the attacks. The stand-down of al-Sadr's men over the past year has been pointed to as a sign of the U.S. troop surge's success. Now, however, many Iraqis speculate that the Mahdi Army is hoping to revitalize its street cred by seizing a murderous new role: as guardians of morality.

Western attention has always focused primarily on sectarian attacks in Iraq. Yet al-Sadr's militia and its counterparts in countless neighborhoods and towns have long had other targets in their cross hairs. These men claim to bear the banners of religion and morality, defending against any transgressors. They paint themselves as the caretakers of tradition, culture, and national authenticity -- which often means keeping women, as well as men, in their rigidly enforced traditional roles. Ironically, they sell their violence as a means of security: Amid the total upheaval of Iraqi society over the last eight years, many people regard any relaxing of gender roles as a threat to public order, undermining patriarchal power. And since the coalition forces failed to provide security after the invasion, such cultural conservatives have moved in to fill the role. Many aimless, unemployed advocates of rigid traditionalism have taken up the task with their guns.

Indeed, since 2003, the Mahdi Army and other militias have targeted women, murdering hundreds if not thousands for working outside the home, for wearing makeup or pants, or just for walking on the streets unveiled. More recently, as attacks on gay men have grown more pronounced, Iraq's media and its mosques have taken up the theme that Iraqi masculinity is under threat. Friday prayers warn that the "third sex" is on the loose in Baghdad cafes. News articles bemoan the "feminization" of Iraqi men, apparent not only by homosexuality but in Western dress and habits, scandalously tight T-shirts and expensive jeans. The hatred of "feminized" men betrays a deep-seated fear of women, and anxiety over the loss of fatherly and familial control.

Assaults on marginalized people, however, never stay at the margins. The fate of the most isolated, vulnerable people is a barometer of whether the law can protect, and the state will serve, all citizens.

We've seen this pattern all too closely before. In the 1990s, Zimbabwe's President Robert Mugabe proclaimed that lesbians and gays were "people without rights," foreshadowing a broader campaign of brutality -- against farm owners and farmworkers, dissidents and demonstrators, newspapers and trade unions. No one was left untouched. In Iraq today, the government's indifference to a similar campaign of murder -- within a stone's throw of the Green Zone -- is a grim augury for the future. Militias, emboldened by their successes, will need and find new victims. The rights and lives of all Iraqis are potentially at stake.

Today, American and Iraqi politicians' televised boasts about the surge and security sound like a cruel delusion in the homes of countless grieving families. There will be no security in Iraq until the government reins in militias and establishes the rule of law. There will be no justice until assaults against invisible victims -- including the epidemic of gender-based violence -- are investigated and punished. Otherwise, these men, whose only crime is looking different, will only be the first victims in Iraq's second surge -- of killings.

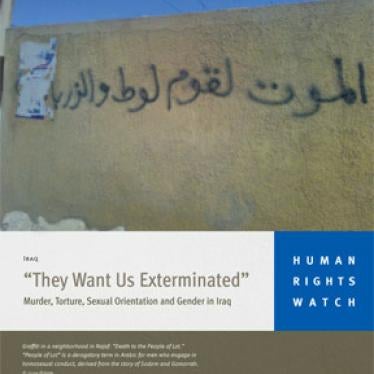

Rasha Moumneh is Middle East researcher for Human Rights Watch, which recently issued a report, "'They Want Us Exterminated': Murder, Torture, Sexual Orientation and Gender in Iraq."