As the FIFA Men’s World Cup begins, Qatar is facing media scrutiny for the abuse and exploitation of migrant workers who built and delivered an estimated $220 billion of World Cup infrastructure—as well as discrimination against women and LGBT people. Qatari authorities are anxious to deflect attention from the country’s human rights record by claiming that the criticism is racist, because such criticism against a World Cup host is “unprecedented.” FIFA President Gianni Infantino said the same, delivering a rambling speech on the eve of the World Cup.

Qatari authorities might be able to justifiably complain about lazy reporting on the Arab world, but the biggest criticism about Qatar is that this World Cup has been built on racial injustice—delivered at the cost of abuse and exploitation of low-paid migrant workers primarily from South Asia and Africa.

Qatar is opposing the call for financial compensation, or remedy, for migrant workers who have suffered abuse over the past 12 years, including wage theft and uncompensated injuries and deaths, as they prepared for the major sporting event, claiming the call for remedy a “publicity stunt.”

The reality is that Qatar operates what a former United Nations special rapporteur on racism, E. Tendayi Achiume, described in 2019 as a de facto caste system based on national origin with the vast majority of low-paid migrant workers coming from Asian and African nations including India, Nepal, Bangladesh, the Philippines, and Kenya.

The roots of modern-day Qatar’s racialized societal and labor systems run deep. Not many people are aware that the Gulf states’ histories—which include the slave trade, indentured pearl divers, and the kafala (sponsorship) system for migrant workers, which cemented racial hierarchies based on national origin—are bound up with the history of the British Empire. From 1871-1913, Qatar was part of the Ottoman Empire, and in 1916 Qatar became a British protectorate after entering into an agreement allowing the British to control its foreign policy in return for British protection until its independence in 1971.

Kafala initially related to the Arab Gulf countries’ customary Bedouin traditions, whereby hosts of foreign visitors took legal and economic responsibility for them as their kafeel, a sponsor or guarantor, including any consequences for their guests’ actions. However, recent academic research argues that the current kafala system—a series of immigration laws and policies that we know today—was largely a British creation during the protectorate period in the early 20th century.

The system enabled British officials to bring in and control large numbers of colonial subjects from South Asia, as well as to extend their control over a broader foreign worker population that increased with the onset of oil exploration. Following independence from British rule, Gulf rulers kept and reinforced the kafala system so that all migrant workers coming to their countries would need a kafeel to take responsibility for their legal status, including whether they could enter or leave the country or change employers.

Qatar is now one of the world’s wealthiest states. It has attracted workers globally through the promise of high wages. The kafala system, however, has enforced a racialized, hierarchical structure. Qatar’s small but powerful minority of its own citizens—around 380,000, which make up about 10 percent of the country’s population of almost 3 million—sits at the top of the hierarchy with state benefits funded by energy wealth, while noncitizens, mostly migrant workers, make up the other 90 percent.

There are migrant workers in Qatar, like the rest of the Gulf Cooperation Council states, from European, North American, and Arab countries who can earn eye-watering incomes in highly paid fields such as consulting and law, often living in a privileged bubble enjoying freedoms that many local citizens envy. Migrants also come from a range of countries to work in middle-income fields such as education and medicine, but the vast majority are low-paid workers in the construction and service sectors from South Asian countries such as India, Nepal, Bangladesh, and the Philippines, as well as increasingly from African countries such as Kenya.

The former U.N. special rapporteur on racism found that for many South Asians and Africans who possess the necessary skills, nationality often functions as a barrier to higher-paying jobs and better contractual benefits. She noted that Qatar’s structural discrimination has meant that “European, North American, Australian and Arab nationalities systematically enjoy greater human rights protections than South Asian and sub-Saharan African nationalities.” Workers are often paid different wages by their employers for the same job based on their nationality, even in low-paid construction and service sectors. The much-touted nondiscriminatory monthly minimum wage of 1,000 Qatari rials (around $275), established in 2020, is so low that it does not combat wage discrimination in practice.

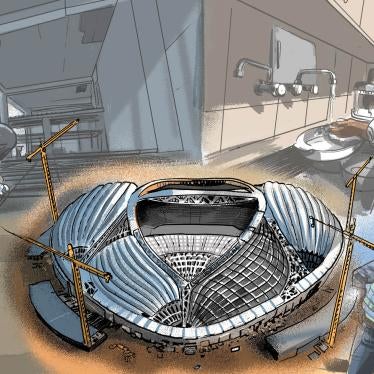

FIFA, when it awarded Qatar the 2022 World Cup in 2010, did not insist on any labor rights conditions even though it knew that it would take hundreds of thousands, even millions, of workers to build the necessary infrastructure. Since that time, Qatar now boasts eight stadiums, an airport expansion, a metro, more than 100 hotels, new roads, and an entire new coastal city.

Qatar, FIFA, and a network of multinational corporations, Qatari-based and foreign employers and recruiters have profited off migrant workers in impoverished circumstances. Qatari authorities’ kafala system and lack of effective labor protections essentially allowed employers and recruiters to charge workers illegal recruitment fees, overwork and deny them their wages, and subject them to grueling working conditions in extreme heat and humidity that left them exposed to injury, sickness, and death.

Hundreds of thousands of male laborers live in large segregated labor camps, in often squalid accommodations. Many low-paid migrant women in the service sector have also been housed in separate accommodations, facing curfews and confinement. Migrant domestic workers, who have weaker legal protections, are often confined to their employers’ homes and remain the most vulnerable to abuses including verbal, physical, and sexual abuse.

Qatar’s labor minister claims “every death is a tragedy,” but Qatar does not treat all lives equally. Thousands of low-paid migrant workers from South Asia and Africa died, but their families were not compensated as their deaths were documented as “natural causes” or “cardiac arrest.”

Qatari authorities deprived these families of an explanation for their loved ones’ deaths, including whether their deaths were related to working conditions, leaving their families uncompensated and in financial distress. Yet they investigated a single British worker’s death at a construction site in 2017, showing they can act when they choose to.

Migrant workers are denied the right to unionize and demand their own rights, but many still risked arrest, deportation, and banishment from reentry to Qatar by telling their stories, assisting fellow workers in distress, striking and protesting wage theft and poor working conditions.

After much international campaigning and negotiating, Qatar made important labor reforms, but they either came too late, were too narrow in scope, or were too weakly enforced for most workers to benefit. In 2020, Qatari authorities undertook crucial reforms to the kafala system to finally allow most workers the right to leave the country without employer permission and to change jobs without needing employer permission.

However, it has been so weakly enforced that many workers remain trapped and are still fighting for their wages. Migrant workers are still required by the government to obtain signed letters approving their resignation from their original employer, essentially enforcing the de facto employer permission to change jobs in practice. Employers also still hold power over workers’ entry, as well as their legal and residence status, and can report workers for “absconding,” invalidating a worker’s legal status even if they are simply escaping an employer’s abuse.

The government’s Workers’ Support and Insurance Fund, which pays out for wage theft when employers have defaulted, only became operational in 2020. The vast majority of workers subject to wage theft before this time did not have access to this fund when their employers refused to pay, with many returning home empty-handed. Even those who applied from 2020 still have problems accessing the fund.

FIFA, which is expecting billions of dollars in revenue from the 2022 World Cup, has failed to address and mitigate the harm caused by Qatar’s exploitative hierarchical systems. Initially, FIFA focused on Qatar’s plans for air-conditioned stadiums to ensure the health of visiting players and fans, many of whom are from wealthier countries, even switching the tournament from the summer to the winter. But soccer’s governing body apparently had little regard for the conditions of millions of low-paid migrant workers who toiled in extreme temperatures of over 122 degrees Fahrenheit (50 degrees Celsius) for years.

A global coalition of human rights organizations, migrant rights groups, trade unions, labor unions, and international soccer fans are supporting migrant workers and their families’ call for compensation for abuses they have faced over the past 12 years while building or servicing the infrastructure for the World Cup, including illegal recruitment fees, wage theft, and uncompensated injuries and deaths. On the eve of the World Cup, FIFA failed to state that it would set aside funds to compensate migrant workers who faced abuse, including the request that it set aside at least $440 million for such a fund, equivalent to the prize money provided to the 2022 World Cup teams.

Conflating genuine calls for compensation with racism may seem to be a useful public relations tactic for Qatar and FIFA, but it is an insult to those migrant workers who have actually suffered under a racialized labor system.

Qatar needs to address the root causes of the racial injustice that threaten the legacy of its World Cup. It should start by committing, along with FIFA, to remedying abuses that have taken place over the past 12 years, including wage theft, injuries, and deaths, and then Qatar should build on its recent reforms to dismantle its kafala system entirely.