(Beirut) – Qatar’s adoption of a new law on domestic workers provides labor rights for domestic workers for the first time, Human Rights Watch said today. Qatari authorities should enact strong enforcement policies and close loopholes that place domestic workers at risk of exploitation.

On August 22, 2017, the Emir of Qatar, Sheikh Tamim Bin Hamad Al Thani, ratified Law No.15 on service workers in the home (“Domestic Workers Law”). The cabinet adopted the law in February. The law guarantees workers a maximum 10-hour workday, a weekly rest day, three weeks of annual leave, and an end-of-service payment of at least three weeks per year. The law does not, however, set out enforcement mechanisms.

“It is a positive step, if long overdue, that Qatar finally enacted a labor rights law to protect its almost 200,000 domestic workers,” said Rothna Begum, Middle East women’s rights researcher at Human Rights Watch. “But these rights will remain only on paper unless the government rapidly creates an enforcement system to give teeth to the law and sanction abusive employers.”

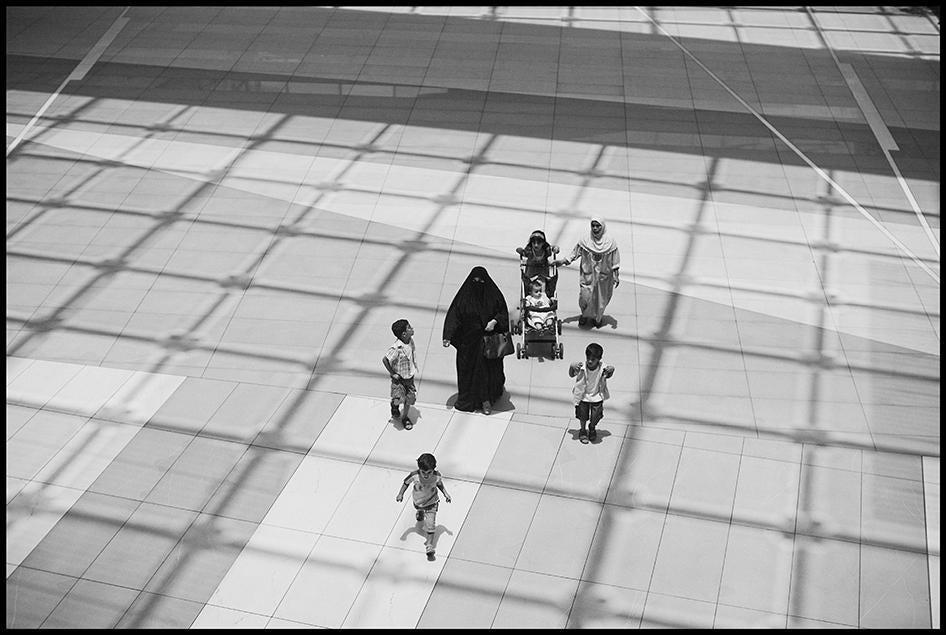

Qatar has 173,742 domestic workers, including 107,621 women, according to the country’s 2016 labor force survey. Most are from Asia or Africa. Domestic workers are excluded from Qatar’s existing 2004 Labor Law protections.

Human Rights Watch has documented abuses against domestic workers in Gulf states over several years tied to the lack of labor law protections and the legally mandated sponsorship (kafala) system, which ties a migrant worker to a particular employer and does not allow a worker to freely change employers.

Abuses include unpaid or delayed wages, confinement to the employer’s house, excessively long workdays with no rest and no days off, passport confiscation, physical and social isolation, and in some cases, physical, verbal, or sexual assault by employers. Domestic workers, like other unskilled migrant workers, often do not speak Arabic and have limited legal protection.

The Domestic Workers Law requires a written contract that details the type and nature of the job, salary, and other conditions. However, the contract’s Arabic text prevails. Human Rights Watch has recommended that workers sign employment contracts in their native language that are notarized as identical to the Arabic version prior to departure from their country. Human Rights Watch has documented numerous instances of contract substitution, in which a worker signs a contract in their native language, only to discover that the Arabic version has less favorable terms.

The new law also sets out minimum requirements governing the employment of any domestic worker, which includes those performing housework, drivers, nannies, cooks, and gardeners, among others. It requires employers to treat workers “in a good manner that preserves their dignity and bodily integrity,” and not to harm the worker physically or psychologically, or endanger the worker’s life or health.

Employers must provide domestic workers with medical treatment for injuries or illness, and compensation for work injuries in accordance with the Labor Law. Employers must also provide food and adequate accommodation, but the law is vague on minimum standards. The law prohibits employers from deducting a worker’s pay to compensate for recruitment fees, but does not require employers to reimburse a worker for recruitment fees already paid.

While the law has a number of positive provisions, it is still weaker than the Labor Law, which protects all other workers, and does not fully conform to the International Labour Organization (ILO) Domestic Workers Convention, the global treaty on domestic workers’ rights.

The Domestic Workers Law provides for a maximum 10-hour working day, while the Labor Law provides for a maximum 8-hour workday and a 48-hour work week. While the Domestic Workers Law provides that the working day should be interspersed with rest breaks, it does not stipulate how often, and breaks do not count as part of the 10 working hours, whereas the Labor Law requires rest every five hours.

The Domestic Workers Law allows overtime, including on weekly rest days if the domestic worker agrees, but does not require overtime pay or state that workers should be free to leave the workplace during their non-working hours.

The new law prohibits employers from forcing domestic workers to work while on sick leave, but makes no provisions for sick leave itself, including whether it should be paid. The Labor Law provides two weeks of sick leave at full pay, four weeks at half pay, and unpaid leave thereafter.

The ILO Domestic Workers Convention requires protections for domestic workers equivalent to those for other workers. Qatar and other Gulf countries should ratify that convention and align their national laws to the treaty, Human Rights Watch said.

“While the new domestic workers law provides domestic workers important labor rights, it still treats them as second-class workers with weaker protections,” Begum said. “The Qatari authorities should close all loopholes that employers could easily exploit and ensure that domestic workers have protections equal to other workers.”

The Domestic Workers Law establishes fines for violations, but lacks provisions for enforcement, such as workplace inspections, including homes where domestic workers are employed. It also does not guarantee the right to form a union or set a minimum wage. Qatari authorities should address these gaps in the implementing regulations, Human Rights Watch said.

Several other Gulf countries have moved more quickly to improve labor protections for migrant domestic workers. Kuwait passed a law in 2015 that provides for a weekly day off, 30 days of annual paid leave, a 12-hour working day with rest, and an end-of-service benefit of one month’s wages for each year worked.

In 2016, Kuwait passed implementing regulations, including overtime limits and compensation, and the only minimum wage for domestic workers in the Gulf region – 60 KD (US$200) a month. While the laws and regulations set out some sanctions for agencies and employers, they lack specific sanctions against employers who fail to provide adequate housing, food, and medical expenses, daily breaks, or weekly rest days, or provide for household inspections.

Saudi Arabia adopted a regulation in 2013 that grants domestic workers nine hours of rest in every 24-hour period, with one day off a week, and one month of paid vacation after two years. But it allows employers to require domestic workers to work up to 15 hours a day, whereas Saudi general labor law limits other workers to eight hours daily.

Bahrain’s 2012 national labor law includes domestic workers and grants them annual vacations as well as mediation for labor disputes, but excludes them from basic protections that other workers receive, such as weekly rest days, a minimum wage, and limits on working hours.

Oman and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) both exclude domestic workers from their national labor laws, although the UAE has a pending draft law on domestic workers awaiting ratification by the president. The Federal National Council says the bill includes 30 days of annual paid leave and daily rest of at least 12 hours, including at least 8 consecutive hours, 15 days of paid sick leave, 15 days of unpaid sick leave, and compensation for work-related injuries or illnesses. However, these provisions are still weaker than the country’s national labor law, and as the government has not made the full text of the draft law public, it is not clear whether it includes enforcement mechanisms and penalties.

“Qatar and its neighbors are moving in the right direction on domestic workers’ rights,” Begum said. “But for these highly vulnerable workers, the Gulf countries need to bolster protections and strongly enforce laws.”