(Beirut) – Migrant workers and their families are demanding compensation from FIFA and Qatar authorities for abuses, including unexplained deaths, that workers suffered preparing for the 2022 FIFA Men’s World Cup, Human Rights Watch said today. Human Rights Watch released a five-minute video in advance of the tournament, which begins on November 20, 2022, in which the workers and their families and football fans from Nepal speak out.

Unlike previous tournaments, the emotions surrounding the 2022 World Cup in Nepal and origin countries, where football is highly celebrated, go beyond the joy of watching the game. For the Nepalis seen in the video, and for those from other countries that sent workers during the 12-year preparations for the World Cup, their realities are entangled with the sacrifices they made. They include parents who were unable to see their children for years to earn money to support their education, workers who endured physical labor for long hours in Qatar’s extreme heat, and families of workers who died from unexplained causes. As Kshitiz Sigdel, an ardent football fan and founder of a fan club in Kathmandu, told Human Rights Watch, “Migrant workers are the backbone not just for Nepal’s economy via remittances, but also the backbone for Qatar’s economy.”

“Migrant workers were indispensable to making the World Cup 2022 possible, but it has come at great cost for many migrant workers and their families who not only made personal sacrifices, but also faced widespread wage theft, injuries, and thousands of unexplained deaths,” said Rothna Begum, senior researcher at Human Rights Watch. “Many migrant workers, their families and communities are not able to fully celebrate what they have built, and are calling on FIFA and Qatar to remedy abuses of workers that have left families and communities destitute and struggling.”

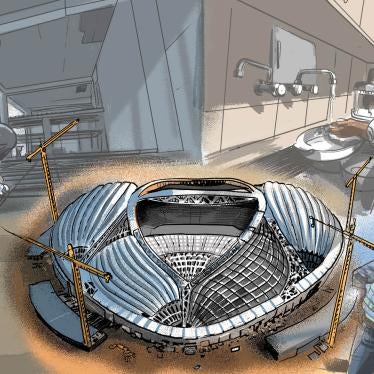

Among those who speak in the video is Hari, whose name was changed at his request for anonymity, a construction worker in Qatar for 14 years who worked in several construction sites including the Al Janoub stadium. He says that the Lusail area of Doha was empty when he first arrived in Qatar but is now full of towers. “We built those towers,” he says, adding that while working in Qatar’s extreme heat, he often had to “pour water (sweat) out of his shoes.”

Hari left Nepal for Qatar when his son was just 6 months old and has missed most milestones in his son’s life, seeing him only 5 times in 14 years. “My son did not recognize me when I first returned to Nepal,” he said. However, in those 14 years away, he witnessed and contributed to Qatar’s dramatic transformation that enabled him to be a better provider for his children, including his son, who dreams of becoming a professional footballer and loves Portugal’s national team.

Ram Pukar Sahani, a former Qatar migrant worker himself, heard about his father’s death in Qatar from a friend. In disbelief, he called his father’s number in Qatar. His father’s friend answered, confirming the devastating news. “I dropped the phone, and I passed out,” he recalls tearfully. He says that his father died at a construction work site in his uniform, but was ineligible for compensation because his death certificate read “acute heart failure due to natural death.”

Under Qatar’s labor law, deaths attributed to “natural causes” without being adequately investigated are not considered work-related and are not compensated. Like families of many other workers left in the dark about what killed their loved ones, he says: “How will someone so healthy and strong just die? I did not believe the news.”

For every family willing to share their stories of loss publicly, many others are coping silently with similarly catastrophic losses, Human Rights Watch said.

Many workers experienced rampant wage theft. A worker who had participated in a strike to protest unpaid wages despite fear of reprisal says: “There are two things we need. Regular work, and regular pay for work completed. Unfortunately, both are not guaranteed in Qatar especially if you land a bad employer.”

In response to such reports, the International Labour Organization (ILO) reported that the Qatari government has reimbursed US$320 million to wage abuse victims through the Workers’ Support and Insurance Fund. But the fund became operational only in 2020. For many other workers, their journey ended abruptly with unpaid salaries for physically demanding work in the extreme heat.

Employers and recruiters in Qatar were able to abuse and exploit migrant workers’ destitution and lack of opportunities in their own countries, under the kafala (sponsorship) system, which gives employers disproportionate control over workers, Human Rights Watch said. In one of the world’s richest countries, migrant workers lived in impoverished conditions in overcrowded accommodations. Despite constructing the multi-billion state-of-the-art infrastructure, the majority of low-paid migrant workers “paid to build” the 2022 Qatar World Cup. And, even with Qatar’s advanced health system, families across Asia and Africa were kept in the dark about what killed their loved ones in Qatar.

Qatari authorities initiated important labor and kafala reforms; but many migrant workers did not benefit, either because they were introduced late, were poorly implemented, or in cases of initiatives by the Supreme Committee, the government entity in charge of preparing for the World Cup, were too narrow in scope. Those who fell through the cracks need financial compensation, Human Rights Watch said.

Basanta Sunuwar, a Nepali who worked for six years in Qatar, describes himself as a die-hard German fan and founder of a football fan club. He says in the video that he considers himself one of the luckier migrant workers in Qatar, and strongly advocates for the compensation fund for unaddressed abuses.

“They gave their labor and in exchange, they should get their rights,” he says. “What is their right now that they have lost their lives? It is compensation. This is my humble request to FIFA and Qataris, as a football fan.”

Football fan, Sigdel, says: “Why are they not agreeing to pay [compensation]? There shouldn’t be any question about paying and not paying. It has to be paid.”

FIFA, which is expecting billions of dollars in revenue for the games and has human rights responsibilities, has not made a commitment to establish a remedy fund. Instead, it scolded football associations and players who have called on FIFA to support migrant workers’ demand to establish a compensation fund, telling them to “focus on the football.” Qatari authorities are opposing the fund but have the data and existing mechanisms that could be used to build and expand on systems to provide a remedy for the abuses.

“A week ahead of the World Cup, FIFA’s strategy to bury their heads in the sand and buy time, hoping that the excitement for the game will overshadow the human rights abuses, is bound to fail,” Begum said. “For fans, especially from origin countries, the tournament will be a reminder of the cost, and the only way for FIFA and Qatari authorities to leave a positive legacy is by committing to a remedy fund to address past abuses.”