Summary

Today, Syrian refugee children in Jordan face a bleak educational present, and an uncertain future. Close to one in three—226,000 out of 660,000—Syrians registered with the United Nations refugee agency in Jordan are school-aged children between 5-17 years old. Of these, more than one-third (over 80,000) did not receive a formal education last year.

There are almost 1.3 million Syrians today in Jordan, a country of 6.6 million citizens. Their arrival, and specifically that of Syrian children, since the outbreak of conflict in Syria in 2011, has spurred Jordan’s Education Ministry to take a number of steps to accommodate their educational needs. These include hiring new teachers; allowing free public school enrollment for Syrian children; and having second shifts at nearly 100 primary schools to create more classroom spaces. In the fall of 2016, the ministry aims to create 50,000 new spaces in public schools for Syrian children, and to reach 25,000 out-of-school children with accredited “catch-up classes.”

Donor aid, while consistently falling short of that requested by Jordan to host refugees, has played an important role in providing educational opportunities, and is set to increase: in February 2016, donors pledged to give US$700 million per year to Jordan for the next three years (although World Bank calculations put the cost of hosting Syrian refugees in Jordan at $2.5 billion annually), with the European Union (EU), United Kingdom (UK), Germany, United States, and Norway pledging $81.5 million in May specifically to support expanding access to education.

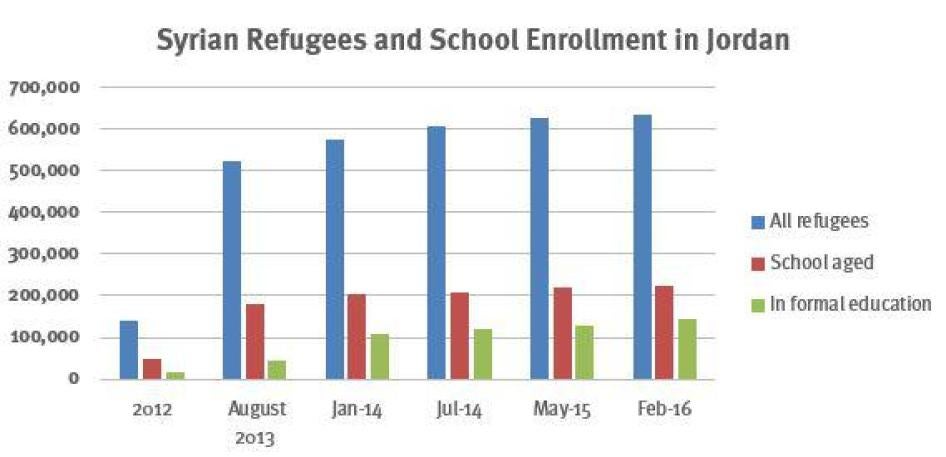

Such initiatives have had impact; between 2012 and 2016, the proportion of Syrian refugee children enrolled in formal education soared from 12 to 64 percent. Moreover, the donor-supported plan announced in February should significantly improve access to education for Syrian refugee children without lowering the quality of education for Jordanian children—a common concern.

Yet tens of thousands of Syrian children have remained out of classrooms, a problem that gets more acute as they get older and enrollment rates plummet.

This report addresses some of the key reasons why Jordan, despite increased efforts, has been unable to enroll more Syrian children in schools and keep them in the educational system. It also highlights key areas that should be addressed if the fundamental right of Syrian children to education is to be realized, and the foundation laid for them to be able to contribute meaningfully one day to Syria’s reconstruction.

***

Part of the solution is economic. Jordan spends more than 12 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP) on education, more than twice as much as countries like the US and the UK. But its public school system, strained even before the Syria conflict, needs more financial support.

Existing policies that prevent Syrian boys and girls from going to school also need to be removed. For example, refugee registration policies that require school-aged children to obtain identification documents, or “service cards,” to enroll in public schools may have prevented thousands from doing so. Such cards are virtually unobtainable for tens of thousands of Syrians who left refugee camps without first being “bailed out” of the camps by a guarantor—a Jordanian citizen, a first-degree relative, and older than 35—after July 2014, when a new policy was introduced. Since February 2015, Jordan has also required that all Syrians obtain new service cards, although schools have allowed children to enroll with older cards. As of April 2016, about 200,000 Syrians outside refugee camps still did not have the new cards, and humanitarian agencies estimate tens of thousands of them may be ineligible to apply.

Certification and documentary requirements create additional barriers to enrollment for older children. Requirements of some school directors that children show official Syrian school certificates proving they completed the previous grade are impossible for many families that fled fighting in Syria without bringing originals. Up to 40 percent of Syrian refugee children in Jordan lack birth certificates, which are required to obtain service cards. Lack of birth certificates will pose a barrier to enrollment to increasing numbers of children as they reach school age.

Education Ministry regulations that bar school enrollment to all children, Jordanian and Syrian, who are three or more years older than their grade level, pose yet another barrier to Syrian children: according to a 2014 United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimate, the “three-year rule” barred some 77,000 Syrian children from formal education. A plan agreed upon by the Education Ministry, foreign donors, and United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) beginning in the 2016-2017 school year will help to boost enrollment of out-of-school children by allowing up to 25,000 children to enroll in a “catch-up” program, which will teach two grades of material in a single year, after which they will be eligible to re-enroll in formal education. However, the program will only be open to children aged 8 to 12. The Education Ministry has also accredited a nongovernmental organization (NGO) to teach a similar program for older Jordanian and Syrian children, which is being expanded with donor support. But the program has reached only a few thousand children, leaving many older children with no pathway back to school. In addition to increasing the scope of such programs, Jordan could help out-of-school children older than 12 access education by waiving the “three-year rule” and regularizing school entrance and grade placement tests, currently offered only once a year.

Poverty and work restrictions further curtail access to education. While Jordan has made public schools free to Syrian refugees, many Syrian parents cannot afford school-related costs, such as transportation (there are no public school buses in Jordan). A 2015 UN assessment found that 97 percent of school-aged Syrian children are at risk of non-attendance because of their families’ financial hardship. Nearly 90 percent of Syrian refugees live below the Jordanian poverty line of $95 per person per month; none of the families that Human Rights Watch interviewed earned that much.[1] Most Syrians are in debt to their landlords, and rents have increased threefold or more in some communities, according to NGOs; Jordanians have also been affected and some have been evicted by landlords seeking higher rents.

Donor assistance helps counter these pressures, but has been inadequate and unpredictable. The World Food Programme ran out of adequate funds in August 2015 and temporarily cut off all support to 229,000 of the refugees in host communities (and halved it to $14 per month for the remainder of the non-camp population). The following month, “voluntary returns” of refugees to Syria accelerated to up to 340 per day.

The impact of poverty on school enrollment and attendance is exacerbated by Jordanian policies that effectively prevent many Syrian refugees from supporting themselves through work. Few Syrians have been able to meet the requirements for lawful work permits, which include paying fees that cost the equivalent of hundreds of US dollars annually and finding an employer to sponsor them. Syrians who work without permits face being arrested and sent to refugee camps: Jordanian authorities have arrested more than 16,000 Syrians and sent them to the Azraq refugee camp due to lack of residency documents or work permits.

Increasingly in debt, lacking adequate humanitarian support, and at risk of arrest for working, around 60 percent of Syrian families in host communities rely on money earned by children, who consequently drop out of school to work. Very few re-enroll. Several families interviewed for this report said that income earned by their children went towards school transportation for siblings, or medical treatment for sick relatives.

Policies limiting access to lawful work permits also increase the likelihood of exploitation, low wages, and hazardous jobs, since the Syrian employee is at greater risk from complaining than the employer. All of the children whom Human Rights Watch interviewed described work that violated international and Jordanian labor laws, which prohibit work for long hours, in hazardous conditions, and for children younger than 16.

Jordan’s effective bar on lawful employment for Syrian refugees has been a disincentive for Syrian children to finish secondary school. Few Syrians can afford to pay for vocational training colleges, while others lack necessary documents to enroll, and some NGOs said that Jordanian authorities had not approved their vocational training projects, possibly due to fears that Syrians will compete with Jordanians for jobs. Donors have offered to fund more technical and vocational education programs for Syrians, and fund some university scholarships for Syrian students, who pay higher rates as non-citizens than do Jordanian students.

In April 2016, Jordan temporarily stopped enforcing penalties against Syrian refugees working without permits and waived the fees to obtain them during a three-month grace period, which it has extended; some 20,000 permits were issued by August. An estimated 100,000 Syrian workers were ineligible, however, because they did not have a service card and were not sponsored by a Jordanian employer. In February 2016, Jordan pledged to issue up to 50,000 work permits for Syrians in sectors where they would not compete with Jordanians, and said it would open— depending on future investment and donor support—“special development zones” where up to 150,000 Syrians could be hired to manufacture products for export, primarily for European markets. The Council of the European Union decided in July to grant such products tariff-free treatment. UNHCR had previously negotiated 4,000 work permits for Syrians to produce textiles.

Jordanian registration requirements and policies restricting access to work, healthcare, and education have pressured Syrian refugees to remain in refugee camps—where life is harsh, despite donor aid—or to move there from host communities.

In 2015, a lower percentage of Syrian children were enrolled in school in these camps than in host communities. Surveys by UN agencies found that barriers to education in such camps included long distances to school within large camps, and among some children, “a sense of the pointlessness of education as they had limited hope for their future prospects.”[2] More schools were opened in Zaatari camp, the largest, in 2015—where there were 9 formal schools—but at the time of a Human Rights Watch visit in October, some lacked electricity, running water, and windows.

Jordan’s generous provision of free access to public schools to Syrian children has also increased the pressure on primary schools in intake areas. This in turn poses challenges to ensuring a quality education, and has stoked intercommunal tension in some towns where Jordanians see Syrian refugees as increasing class sizes, and straining school resources. Some Jordanians who had enrolled their children in private schools but could not continue to send them for financial reasons reportedly found nearby public schools were full due to increased Syrian enrollment. Even before the Syria conflict, resources in Jordanian schools were strained, prompting dozens of schools to teach classes in morning and afternoon “shifts” to increase classroom spaces. The arrival of large numbers of Syrian refugee children forced Jordan’s Education Ministry to open afternoon shifts for Syrian students at 98 primary schools. To enroll more Syrian children in 2016-2017, the ministry plans to open second shifts at an additional 102 schools.

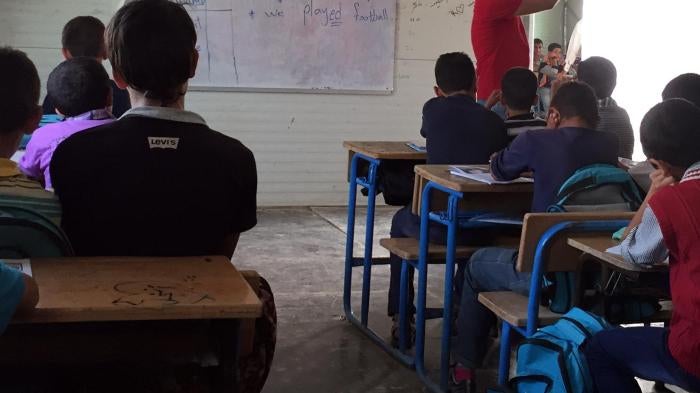

Jordanian and Syrian students in schools that operate two shifts have received fewer hours of instruction than children attending schools operating on regular hours. School facilities like libraries were closed during afternoon shift classes, which only Syrian students attend. Students in refugee camp schools also received fewer hours of instruction than students in single shift schools. In one large school in Zaatari, classes run for 35 minutes, with no breaks in between, no recess, no time to eat, and no access to computer facilities. Some teachers in refugee camp schools said they did not receive any teacher training, and only had to show they had graduated from university; in general, public school teachers should receive teacher training, but many have not been adequately trained.

Teachers in host communities and in refugee camps said they found it difficult to teach some Syrian children who showed clear signs of trauma. A growing number of Syrian children receive psychosocial support, but others who need help drop out of school. One boy’s mother said his personality changed during the conflict after his cousin was killed in an attack and the boy retrieved his head, and he no longer wanted to go to school in Jordan. Refugee families as well as Jordanian teachers complained of unmotivated teachers and overcrowded classrooms with up to 50 children, particularly in Zaatari camp.

These difficult circumstances have apparently contributed to a preexisting problem of corporal punishment—officially prohibited—and violence in Jordanian schools. Syrian children described how teachers beat them with sticks, books, and rubber hoses. In other cases, children faced severe harassment by Jordanian children in school or while walking to school; UNICEF reported that 1,600 Syrian children dropped out in 2016 due to bullying. One boy was threatened with being stabbed if he did not give up his pocket change; others were beaten with wires. The parents of a girl with a blood disorder pulled her out of school due to beatings by other children.

***

Qualified Syrian teachers who fled to Jordan represent an untapped resource: they could lower student-teacher ratios and help Syrian students cope with shared traumatic experiences. Jordan has allowed around 200 Syrian refugees to act as “assistants” in overcrowded classes in schools in the refugee camps, but not host communities; non-citizens are banned from teaching in public schools and from registering with the Teachers’ Association. Turkey, by contrast, permits thousands of Syrian teachers to work at fully-accredited education centers that teach a modified version of the Syrian curriculum, in addition to allowing Syrian children to enroll in regular Turkish public schools.

With donor support, Jordan has pledged to allow open 102 more schools on double shifts to accommodate 50,000 more Syrian students in 2016-2017; to open all school facilities, such as libraries, to afternoon shift students; to improve teacher training; and to allow up to 1,000 Syrians, paid with donor support, to act as assistants in schools in host communities. Additional donor support will allow Jordan to substantially increase the amount of time that children in the morning shift spend in class to 30 hours per week, but afternoon shift class time will remain similar to current levels of around 20 hours per week.

Donors including the US, EU, Germany, UK, and Canada have promised to significantly increase support for Jordan to build new public schools, expand and improve existing ones including by making them accessible to children with disabilities, and help subsidize school transportation costs. Donors should promptly and transparently follow through on these multiyear pledges, while also working to ensure that Syrian children in afternoon shift classes receive equal class time to other children in public schools. Jordan should allow regular, independent, quality monitoring in classrooms, and allow qualified Syrian refugee teachers to play a greater role in the education of Syrian children. With international support, it should revise policies that threaten to undermine these significant, positive moves, by ensuring that Syrian children are not barred from school due to difficulties registering with the Interior Ministry.

Better teacher training and accountability is critical to enforce the prohibition on corporal punishment and to deal with harassment by other children. Donors concerned with refugees’ rights to education and work and with preventing child labor should encourage and support development projects that support Syrians’ ability to support themselves. Jordan should also consider revising its work permit regulations to reduce dependency on sponsorship, and making the fee waivers it introduced during the grace period permanent.

***

Prior to the conflict, the primary school enrollment rate in Syria was 93 percent.[3] UNICEF has estimated that nearly 3 million Syrian children inside and outside the country are now out of school—demolishing Syria’s achievement of near universal primary education before the war.[4]

UNICEF calculated that the “total economic loss” from lower lifetime earnings for 1.9 million Syrian children inside the country who had dropped out from primary and secondary education in 2011 due to the conflict was $10.7 billion.[5] The figure did not include the cost of lost education for refugee children. Whether they return to Syria or settle elsewhere long-term, children’s lower earning potential could have a deleterious effect on the economies of host countries, while also driving up the cost of aid and government assistance.[6]

Providing education will reduce the risks of early marriage and military recruitment of children, stabilize economic futures by increasing earning potential, and ensure that today’s young Syrians will be better equipped to confront their uncertain futures.[7]

Methodology

This report is based primarily on research conducted in October 2015 in Jordanian host communities including in Amman, Baqaa, Zarqa, Mafraq, Salt, Irbid and villages nearby, and in the Zaatari, Azraq, and “Emirati Jordanian” refugee camps in Jordan. In total, Human Rights Watch staff conducted interviews with 105 refugees and asylum seekers from Syria, including former Palestinian residents of Syria, from 82 households. The interviewed families were identified through local and international nongovernmental organization (NGO) referrals and contacts within the Syrian refugee community of each city.

Not all members of each household were present during each interview. Including members who were not present, Human Rights Watch obtained information on the conditions of 423 Syrian family members, not including 16 family members whom interviewees said had previously left Jordan in an effort to reach Europe. Of the total number of family members, we gathered information about the educational status of 286 children under 18, of whom 213 were school-aged (6 to 17 years old). Of these school-aged Syrian children, 75 were not in school in Jordan, including 18 children who had been enrolled but had dropped out, 25 children who were working, and 13 who had disabilities, according to them or their parents.

Most interviews with refugees and asylum seekers were conducted in Arabic with the assistance of an interpreter. All interviewees received an explanation of the nature of the research and our intentions concerning the information gathered, and we obtained oral consent from each interviewee. All were told that they could decline to answer questions or could end the interview at any time. Participants did not receive any material compensation. Human Rights Watch has withheld identification of individuals and agencies that requested anonymity. Additionally, we have used pseudonyms when requested, and referenced these instances in the footnotes. Pseudonyms may not match the religion or sect of the interviewee.

Interviews in host communities were conducted in Syrian families’ homes; in most cases, we spoke to parents as well as children. Human Rights Watch was careful to conduct all interviews in safe and private places. During interviews in the Azraq and Zaatari refugee camps, which required prior Jordanian authorization, a Human Rights Watch researcher was accompanied by a policeman (in Zaatari) and by two Jordanian security officials (in Azraq). In the “Emirati Jordanian” camp, the researcher was accompanied by members of the Emirati Red Crescent society, which administers the camp. Because of concerns about these circumstances, the researcher limited questions to refugees in these camps to basic information regarding their children’s ages and schooling.

We did not undertake surveys or a statistical study, but instead base our findings on extensive interviews, supplemented by our analysis of a wide range of published materials. Human Rights Watch also requested information from and sought the views of the Jordanian Ministry of Education. In addition, we met with representatives from the United Nations Children’s Fund, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, international and local NGOs, donor country embassies and aid agencies, nine Jordanian public and private school directors and teachers, and informal education providers. We also consulted with experts in education in emergencies and Jordanian education policy.

Note on currency conversion: the Jordanian dinar is pegged to the US dollar at an exchange rate of 1.4 US dollars per Jordanian dinar.

I. Background

Syrian Displacement to Jordan

There are about 657,000 Syrians in Jordan who have registered as asylum seekers with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). A Jordanian government census carried out in late November 2015 found a total population of 9.5 million people, including 6.6 million Jordanian citizens and 1.265 million Syrians.[8]

The residency status of the 608,000 Syrians counted in the census but not registered as asylum seekers is unclear. Staff at international humanitarian nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) said they estimated that up to several hundred thousand Syrians lived and worked there before the conflict, but that most Syrians in Jordan arrived after fighting began in 2011, and noted the census counted as Syrians anyone with a Syrian passport, including those married to Jordanian citizens.[9] More than half of registered Syrian asylum seekers in Jordan are children, and around 35 percent of the total are school-aged, or 5 to 17 years old, according to UNHCR.

Around 141,000 registered Syrian asylum seekers were living in three main refugee camps as of July 2016. Most of the 516,000 refugees outside the camps live in the Amman, Mafraq, and Irbid governorates, in poor areas where public schools are strained.[10]

The number of Syrians registered as asylum seekers with UNHCR in Jordan initially accelerated rapidly, from fewer than 3,000 in 2011 to more than 400,000 who registered in 2013 alone.[11] The rate of arrivals slowed after Jordan began restricting or closing its border crossings with Syria in 2013.[12] The total registered Syrian refugee population grew from 623,000 at the end of 2014 to 657,000 as of mid-July 2016: an increase of only 34,000 people in more than 18 months.[13] However, as of July, up to 100,000 Syrians who were not registered with UNCHR were stuck in a remote desert location in the northeast.[14]

Registration Requirements

Jordan has not signed the 1951 Refugee Convention or its 1967 Protocol, and Jordanian law does not recognize Syrian refugees as such. Jordan allows UNHCR to register and provide humanitarian assistance to refugees under a 1988 Memorandum of Understanding. This was amended in 2014 to increase the six-month validity period of the temporary protection status that Jordan grants to Syrians; it is now renewable indefinitely for one-year periods.[15]

Until 2015, Jordanian authorities first sent new arrivals from Syria to “reception centers” for initial registration, where until December 2013 authorities confiscated and retained some of the refugees’ official Syrian documents. Jordan then sent the refugees to camps, of which Zaatari, opened in July 2012, and Azraq, opened in April 2014, are the largest.[16]

Refugees in the camps who wished to relocate to host communities in Jordan could do so lawfully under a process known as the “bailout” system, which requires that they be “guaranteed” by a Jordanian citizen who is a direct relative over the age of 35. Initially, Jordan allowed refugees to leave the camps if their Jordanian sponsor paid a fee of 15 dinars (US$21) per person.[17]

For several years, Jordan did not strictly enforce the bailout system. Many Syrians who left the camps without being bailed out were still able to register with UNHCR in host communities and received UNHCR “asylum seeker certificates,” which identified the bearer as a “person of concern.”[18] Syrians with these certificates were eligible to receive humanitarian assistance, such as cash and food aid, provided by UN agencies in host communities. Syrians who left camps without being bailed out were also able to receive identification documents from the Ministry of Interior (MOI) by registering at the local police station, as required by Jordanian law.[19]

Syrians registered with the Interior Ministry are issued a “service card,” which is required to access medical care at subsidized rates at public hospitals and to enroll children in public schools.[20] The service card is valid only in one of Jordan’s 52 districts where it was registered; refugees who move must re-register with police in their new location.

Jordan began to strictly enforce the bailout system in July 2014, when it instructed UNHCR not to register Syrians in host communities who had not been bailed out of refugee camps. The Interior Ministry also refused to issue them “service cards.” As a result, Syrians who left the camps informally after that date cannot obtain the documents required to access humanitarian assistance, subsidized healthcare, and enroll their children in schools. An estimated 120,000 refugees from Syria living outside refugee camps cannot meet the requirements of the bailout system.[21]

Since July 2014, Jordanian security forces have arrested and involuntarily relocated refugees without UNHCR asylum seeker certificates or MOI service cards to refugee camps. According to available statistics, from April 2014 to September 2015 police involuntarily relocated more than 11,000 refugees to Zaatari and Azraq camps, including dozens of children unaccompanied by their parents, largely because they had left the camps without being bailed out or they were caught working without a work permit.[22]

A joint report by a group of international humanitarian organizations published in September 2015 described one case in which Jordanian authorities deported a boy arrested in Amman to Syria because he could not produce required documents; staff at an NGO described a similar arrest and deportation of another boy in mid-2015.[23] In other cases, Jordanian authorities arrested and deported Syrian men who did not have legal documentation, their relatives said. A Syrian man who lives near Irbid said that in the summer of 2015, Jordanian police arrested his 45-year-old brother at work, determined his service card was fake, and “gave him a choice of going to Azraq [camp] or to Syria.”[24] His wife first learned of his whereabouts three days after his arrest, when he called her to say he was in Syria and that she should join him with their children, which she did.[25]

In June 2014, Jordanian security forces also forcibly evicted hundreds of Syrian refugees who had been living in five informal tented settlements in the southern Amman governorate.[26] In one case, Syrians who had been living in an informal settlement near Sahab were bussed to Azraq camp with whatever possessions they could carry, after which bulldozers demolished their encampments, including two tents that had been used as informal schools, with supplies and teachers supported by an NGO.[27]

Poverty

The Syrian refugee population is overwhelmingly poor, and poverty affects Syrian access to education. The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) reported that the families of around 15,400 Syrian children were unable to afford to send them to school in February 2016, and that almost another 10,000 children had dropped out or attended school irregularly because of financial hardship.[28] Most Syrian families, UNICEF found, are trying to cope with poverty while also prioritizing education: 93 percent said they cope with financial hardship by reducing the amount they eat or spend on food, but only 8 percent dropped children from school, despite associated expenses of 20-30 Jordanian dinars (JD)($28-$42) per month per child.

Jordan has worked with international humanitarian agencies to alleviate Syrians’ poverty, including a UNICEF program reaching 55,000 children with JD 20 ($28) per child to reduce pressure for child labor and dropouts, a UNHCR program reaching 30,000 individuals and households; and a World Food Programme (WFP) monthly payment of JD 20 ($28) to registered Syrian refugees in host communities.[29] But these programs are undermined by Jordanian policies that restrict Syrians’ ability to work, even informally, and contribute to child labor and school dropouts.

- Around 86 percent of Syrian refugees live under Jordan’s poverty line (JD 68 or $96 per person per month);

- One in six Syrian refugees live on less than $1.30 per day (or around $40 per month), which UNHCR assessed as the absolute poverty line.[30]

- Syrian refugees in in northern Jordan, where most live, pay an average of $211 per month in rent, which consumes 55 percent of their income.[31]

Jordanian government figures indicate rent increased 14 percent nationwide from 2013 to 2015.[32] In some areas, rent prices soared up to 600 percent after 2011.[33]

Low-income Jordanian families also faced higher rents; unable to pay, some were evicted by landlords, fuelling anti-Syrian hostility in some host communities.[34] Syrian refugees have also faced increased healthcare costs: Syrians with Ministry of Interior service cards could access free healthcare until November 2014, but now pay at subsidized rates.[35]

In addition, in August 2015, about 229,000 “vulnerable” Syrians in Jordan who were below the country’s poverty line experienced cut-offs in humanitarian food aid, while aid was reduced by half for the “extremely vulnerable,” due to lack of funds; the World Food Programme was only able to resume aid at reduced levels in November.[36] Similarly, the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA) stopped providing housing assistance to Palestinian refugees from Syria in Jordan in July 2015 due to funding shortfalls.[37] More than 60 percent of Syrian refugees living in host communities are highly indebted, even with humanitarian assistance, a UNHCR assessment found in May 2015.[38] A 2014 study found that a third of refugees in Jordan were in debt to their landlords.[39]

Increasingly restrictive policies that Jordan imposed after July 2014, combined with unpredictable cut-offs in humanitarian assistance, contributed to thousands of Syrians returning from Jordan to Syria in 2014 and 2015 under an official “voluntary” process, with the flow increasing dramatically to several hundred daily in August and September 2015, after Syrians in host communities were told their food assistance would be cut off or reduced.[40] The International Organissation for Migration (IOM) estimated in August 2015 that the number of returns could reach 50,000 that year.[41]

One man chose to remain in Jordan after the aid cut-off only because his home in Syria had been destroyed, he said: “There’s nothing left there in Hama for us now.”[42] Most who did return went to Daraa, a province bordering Jordan, where the largest percentage of Syrians in Jordan came from, despite ongoing conflict there.[43]

The WFP noted that returns decreased amongst Syrians in refugee camps, where assistance was not reduced, but increased by 17 percent amongst those in host communities.[44] In some cases, refugees chose to leave Jordan in an effort to reach Europe after relatives were arrested for working without permits.[45]

Education in Jordan

At the beginning of the fall semester of 2015, 1.9 million students enrolled in public, private, military, and UNRWA schools in Jordan, from pre-primary to secondary school.[46]

Jordan spends a substantial part of its gross domestic product (GDP) on education: 12.2 percent of its GDP per capita in 2011 (the last year for which figures are available), compared to 5.1 percent in Syria (2009), 1.6 percent in Lebanon (2011), and 2.9 percent in Turkey (2006).[47] The US spent 5.2 percent and the United Kingdom (UK) spent 5.8 percent of their GDP in 2011.[48]

School is divided into two years of pre-primary education, 10 years of primary education, and two years of secondary education.[49] In 2014, Jordan made the second year of pre-primary school compulsory, but due to a dearth of schools in much of the country, parents wishing to send children to pre-primary education must often pay for private schools.[50]

Primary schooling in Jordan is free and compulsory.[51] Students who pass a 10th grade exam are eligible to attend two further years of secondary education, which—depending on their grades—may be geared to university study in the sciences or humanities, or towards vocational or professional training.

After these two years, students can take the standardized graduation exam, the tawjihi. On passing, they receive a General Secondary Education Certificate and are eligible to attend public or private community colleges or universities, or vocational schools. University students are put in academic programs depending on their tawjihi grade.[52]

The Ministry of Education reported net enrollment rates of 38.26 percent in pre-primary school, 98.02 percent in primary school, and 72.56 percent in secondary school during the 2014-15 academic year.[53] Jordan’s net primary school enrollment rate, before and since the Syria conflict began, has remained at around 97 percent, according to the World Bank.[54]

However, even before the Syria crisis, Jordan’s education system faced challenges.

Poverty—including inability to pay transport costs—has undermined the ability of many Jordanian children to attend school: in 2011, United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) reported that around 119,000 Jordanian children were not in school.[55] In 2014, UNICEF reported close to 77,000 Jordanian children aged 5 to 15 were not in school.[56]

Public schools have also long been overcrowded: 36 percent of public schools were overcrowded in 2011, according to the Education Ministry, especially in areas where large numbers of Syrian children have subsequently arrived. Overcrowding is now closer to 47 percent.[57] To make more classroom space available, some Jordanian schools operated on double shifts or in rented buildings even before 2011. This reduced costs per student, but lowered the quality of education. Jordan had committed to move all schools to single, day-long shifts in 2010.

More than half the country’s secondary school students who sat for their tawjihi examinations failed in 2014 and 2015.[58] In both years, there were more than 325 public schools in which not a single student who sat for the exam passed.[59]

About 25 percent of students in Jordan are enrolled in private schools, which range in cost from around $1,400 to more than $10,000 annually.[60] In 2014, around 8,000 of 130,000—6 percent—of Syrian students enrolled in formal education were in private schools.[61]

Human Rights Watch visited a Christian primary school in East Amman that has made scholarships available to dozens of Syrian students, with private financial support; teachers and administrators described programs offering academic and psychosocial support to Syrian students, and specific measures to prevent discrimination against Syrians by other students.[62]

II. Jordan’s Education Policy for Syrian Refugees

Just over one-third, or 36 percent, of Syrian refugee children in January 2016 were school-age, according to Education Ministry estimates.[63]

From the start of the Syria conflict, Jordan granted refugees with required documents free access to public schools in host communities.[64] It also opened accredited public schools for them in refugee camps that opened in 2012 (Zaatari) and 2014 (Azraq).

Syrian refugee children in host communities with necessary documentation—generally asylum seeker certificates issued by United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), and service cards issued by the Ministry of Interior—can enroll for free in public primary schools, beginning grade one for six-year-olds.[65] Syrian children aged four and five can enroll in two years of pre-primary school in Jordan, although most such kindergartens are private and charge tuition. Syrian children must meet other requirements to enroll in Jordanian secondary school (see below).

Due to the steps that Jordan has taken to accommodate Syrian refugee children in its school system, UN agency figures show that the proportion of Syrian 5 to 17-year-olds enrolled in school has steadily increased, along with the growing number of refugee children.[66] As of April 2016, some 145,000 Syrian children were enrolled in formal schools, meaning that around 80,000 school-aged Syrian children were not.[67] As of April 2015, 35,000 Syrian children were on waiting lists for public schools, according to the Ministry of Education.[68] Of those not in formal education, around 15,000 received non-accredited, informal schooling from nongovernmental organizations (NGOs); 32,000 had no education at all.[69]

Source: UNHCR and UNICEF data.[70]

The overall figures may be an undercount, since they are based on enrollment only among Syrians who are registered with UNHCR, and do not capture the number of Syrians who were school-aged children when they arrived in Jordan and who were unable to enroll, have never gone to school, and are now 18 or older. There are no formal educational opportunities for these young Syrian adults. Unless accredited informal or non-formal programs become more widely available, many Syrians in this demographic group have no chance to obtain secondary and even primary education.

The current situation for Syrian refugees contrasts sharply with high education and enrollment rates prior to the conflict in 2010 when net primary and secondary school attendance rates were 93 and 67 percent respectively.[71]

Double Shift Schools

In 2013, the Education Ministry sought to accommodate the growing number of Syrian students in host communities by splitting the day in some schools into two half-day “shifts.” By April 2014, there were 98 double shift schools in host communities.[72] These double shift schools have become “the main tool for providing education” to Syrian children.[73]

Each class is shortened and Syrian students attend either in the morning or afternoon.[74] Jordanian children attend only in the morning. In the Zaatari, Azraq, and Emirati Jordanian refugee camps, the Ministry of Education operates UNICEF- or Emirati-funded schools for Syrian children that also operate on two shifts: girls in the morning, boys in the afternoon.

- As of April 2016, there were nine formal schools in Zaatari, with 20,771 children enrolled according to UNHCR.[75] The nine schools had space for 25,000 school-aged children.[76] However, UNESCO reported that as of June, there were 30,000 school-aged children, of whom half were out of school.[77]

- As of May 2016, there was primary and secondary school capacity in Azraq for 5,000 children, with 3,000 enrolled, and an additional 400 children in kindergarten, out of a total of 15,336 children aged 5 to 17.[78] The number of children enrolled increased from December 2015, when 2,600children were enrolled, but only 1,700were attending.[79]

- As of October 2015, in the Emirati Jordanian camp (supported by the United Arab Emirates), there were 2,000 out of an estimated 2,300 school-aged children enrolled in formal schools operated by the Education Ministry, including 297 boys in grades 7 through tawjihi.[80]

In total, as of November 2015, 63,088 Syrian primary school students (grades 1-10) were enrolled in the regular curriculum in host communities; 49,064 were enrolled in second shifts in host communities; and 25,736 in refugee camp schools, according to the Ministry of Education.[81] Enrollment rates decrease even more precipitously for Syrian students in secondary school: there were 3,318 students in regular schools, 1,589 in second shifts, and only 464 in refugee camp schools.

All teachers at public schools, whether in host communities or refugee camps, must be Jordanian citizens and are paid by the Education Ministry.[82] Teachers in refugee camp schools and in host communities who only teach afternoon shift classes—in other words, teachers who only teach Syrian children—are hired on contracts and do not receive paid vacations, health insurance, or other benefits that full-time teachers receive. Second shift teachers do not receive the same level of teacher training as do full-time teachers.[83] Jordan has permitted around 200 Syrian refugees to work as “assistants” to help classroom management in overcrowded classes of more than 45 students at public schools in the refugee camps.[84]

Non-Formal and Informal Education

Some opportunities for education exist for children who are not in school, including those not eligible to enroll because they do not have the required documents. The largest such program, Makani (“My Place”) is funded by UNICEF. As of December 2015, 38,400 of the most vulnerable Syrian and Jordanian children were receiving psychosocial support, and another 47,000 had accessed life skills training.[85]

A number of community-based and religious charitable organizations in host communities offer a variety of non-formal programs. For example, a school operated by an organization established by a Muslim imam in the city of Mafraq offers three classes per week to students unable to enroll in public schools, based on the Jordanian school curriculum.[86] Syrian parents in other communities said informal programs taught children to memorize sections of the Quran, and Arabic language lessons.[87] In general, little is known about the quality or scope of education of informal and non-formal programs.

Most non-formal programs do not offer any certificates accredited by the Education Ministry, and students who complete the programs are ineligible to enroll in formal public schools. In the refugee camps, Relief International, a humanitarian NGO, operates remedial education programs for children enrolled in public schools.[88]

The Norwegian Refugee Council offers an accelerated learning program in the refugee camps to out-of-school children aged 8 through 12, who received a condensed curriculum that covers two years of schooling in eight-month “levels,” from grade 1 up to grade 6.[89] As of August 2015, only 1,550 children who had completed such programs had enrolled in public schools.[90] Outside the camps, accredited informal education programs that can allow children to re-enroll in public school are available only to children aged 13 and older.[91]

UNRWA Schools

Jordan hosts around 2 million Palestinian refugees who are registered with the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA). These include some 17,000 Palestinians who had fled to Jordan from Syria after 2011.[92]

The relatively small number of Palestine refugees from Syria in Jordan reflects harsh restrictions: since January 2013, Jordan has systematically denied Palestinians from Syria access to the country and deported hundreds back to Syria.[93]

UNRWA provides assistance and services to registered Palestine refugee children in Jordan as well as Palestinian arrivals from Syria, including basic education for grades 1 through 10. In addition to Palestinian children from Syria, some 1,700 Syrian children whose families moved to Palestinian refugee camps in Jordan have also enrolled in UNRWA schools.[94]

Some UNRWA schools operate on double shifts due to overcrowding and budget shortfalls; around a third of Palestinian refugee children attend Jordanian public schools, particularly those who live far from UNRWA schools.[95] Other refugee populations registered with UNHCR, which include 50,000 Iraqis and around 5,000 Somalis and Sudanese, largely depend on Jordan’s public school system.[96]

Donor Support and Jordan’s Plans to Improve Access

Syrian refugees’ access to education in Jordan depends on government-run or approved programs that, in turn, depend substantially on international humanitarian support. In addition to free primary and secondary education, Jordan provides subsidized healthcare to Syrian refugees and subsidizes a number of basic goods available to all people in Jordan, including refugees, such as bread, fuel, water, and electricity.[97] Municipal services also bear the strain of population growth;[98] in May 2014, Jordan told the UN it paid around 80 to 85 percent of the $4 billion annually required for services to Syrian refugees.[99]

According to a 2016 World Bank estimate, hosting Syrian refugees has cost Jordan over US$2.5 billion a year, equivalent to 6 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) and 25 percent of annual government revenue.[100] In 2015, the Jordanian international cooperation ministry’s director general said schooling Syrian refugees at public schools cost $193 million annually.[101] In 2014, Jordan also took out a $150 million loan to cover refugee education and healthcare.[102] Donors have played an important role in supporting the refugee response.[103] The European Union provides around 25 million Euro ($28 million) annually in direct budgetary support to the Ministry of Education for Syrian and Jordanian students.[104]

Other donors have helped to improve and expand public school infrastructure. USAID stated it had expanded 20 Jordanian schools and opened a new one in 2015, and that from 2016 to 2020 it would “invest $230 million to build 25 new schools and 300 kindergarten classrooms, expand 120 existing schools, and renovate 146.”[105] Canada has pledged $20 million to improve teacher training. Some donors have significantly expanded programs that pre-existed the Syria conflict, such as a multiyear “Education for the Knowledge Economy” reform project, to which the World Bank had previously given $407.6 million.[106]

However, to date, foreign donations have consistently fallen far short of needs.[107] In 2015, donations met only 62 percent of the requested humanitarian response in 2015 for Syrian refugees in Jordan, leaving a gap of nearly $453 million.[108]

In total, Jordan received $180,974,150 in grants under the UN-coordinated Syria response plans for the education sector in 2015, including projects directed towards refugee education as well as “resilience” projects intended to benefit Jordanian host communities.[109] Although the education sector received 85 percent of the funds requested in 2015 to address Syrian refugee children’s education, much did not arrive until the third and fourth quarters—too late to adequately plan for or use in the 2015-2016 school year.[110]

Funding for education constitutes 7.7 percent of the overall appeal for humanitarian support in the UN-coordinated regional response plans to the Syria conflict in Syria, Jordan, Lebanon, Turkey, Iraq, and Egypt. Only 37 percent of funding requests for education in these countries was met in 2014, and 20 percent in 2015, leaving a $178 million gap.[111]

In February 2016, donors pledged $700 million per year in grants and concessional development financing for 2016-2018 to support Jordan’s efforts to host refugees, including funding for infrastructure used by Jordanians and Syrians in host communities, such as for education.[112]

III. Barriers to Education

Jordan has lacked adequate resources to open and maintain enough classrooms for Syrian children; hire and train enough teachers to provide a quality education; or reduce school-related financial hurdles to enrollment, such as transportation costs.

In May 2016, donors and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) announced an agreement with Jordan to fund 50,000 additional classroom spaces, in part by placing an additional 102 schools on the double shift system, and improve teacher training. Jordan and donors also agreed to dramatically expand a program that would reach out-of-school children aged 8 to 12, and enable them to re-enroll in public schools.

These steps could address many of the barriers to education that this report identifies. However, as described below, some Jordanian policies also constitute continuing barriers to Syrian children’s right to an education in host communities.

Registration Policies

According to official policy, in the years after Jordan opened its refugee camps (beginning in 2012) until it largely closed its borders in 2015, Syrian refugees who entered Jordan were sent to refugee camps, from which they could apply to be “bailed out” by a Jordanian relative aged 35 or over. In practice, before July 2014, Jordan allowed refugees who left camps without going through the bailout process to receive the Ministry of Interior service cards that are required to access government services.[113]

But in July, Jordanian authorities began to enforce the bailout requirements more rigorously, and ended the bailout process altogether in 2015. An estimated 45 percent of Syrians left refugee camps without going through the bailout process. These refugees have not been allowed to register with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) (and thus obtain asylum seeker certificates) or obtain service cards[114]—rendering them ineligible to receive humanitarian assistance or to enroll children in public schools.[115]

Only two of the six Syrian families interviewed who moved from refugee camps to host communities in or after July 2014 were able to enroll children in public school. Both did so via exceptional circumstances.

In the first case, Abeer, 30, whose family left Azraq camp in October 2014 without going through the bailout procedure only managed to enroll her youngest children—nine-year-old twins—in school because the director made a “special exception” and let her use old service cards the family had received in 2013 when it first came to Jordan from Homs for five months.[116] In the second case, Ghada, 30, said she could only register her three children in primary school after they left Zaatari in October 2014 without being bailed out because an Interior Ministry official with connections helped her “because he felt so bad for the kids.”[117]

In the other four cases, parents said they were unable to enroll their children in school because they lacked the required documents. In one case, Rasha, from Ghouta, left Syria in June 2014 and was sent to Azraq camp. She said her family left Azraq in August that year after her daughter, Khadija, developed bad asthma.[118] The family did not have a Jordanian relative who could bail them out and could not afford to pay other Jordanians to act as one.[119] Since they left the camp after July 2014, the family does not have asylum seeker certificates or service cards. They moved to Baqaa, a Palestinian refugee camp outside Amman, and were unable to enroll any of their three children in school. Rasha said:

I tried to register the kids in three or four different schools but they all rejected them. They said there was no space, or they needed the ID [the service card]. ‘No ID’ was the problem. The kids can’t go to school like other children. If they don’t have an ID then there’s nowhere to go.[120]

Farah, 30, said that her three school-aged children had been enrolled in first, fourth, and eighth grade in Zaatari camp, where they were sent after they came to Jordan in April 2014, but that because they left the camp without being bailed out in August 2015, she had not tried to enroll them in any schools in the city where they had moved because they lack the necessary papers.[121] “We haven’t tried registering them in school because we’d just be asked for their UNHCR certificates,” Farah said.[122]

According to international humanitarian organization staff, from August 2014 to August 2015, around 11,000 people left Azraq camp without being bailed out, at least one-third of whom are school-aged children. According to Jordanian policy, none of these people is able to receive humanitarian assistance or enroll their children in school.[123] In January 2015 Jordan effectively suspended the bailout system altogether, leaving refugees in camps with no lawful way to move to host communities and to enroll their children in school.

In another case, a man who arrived before July 2014 but did not register with UNHCR also described difficulty enrolling his children in school. Nasser, 53, came to Jordan in 2012 from Deir Ezzor without registering with UNHCR or the government, and “never got asylum seeker certificates...”[124] Two of Nasser’s five school-aged children never enrolled in school in Jordan, and two others dropped out of school after a two-year period expired during which they were able to attend classes despite lacking the required documents. He is afraid that his only child who is still in school will not be able to enroll next year. “We’re afraid for their future,” he said. [125]

“Urban Verification Exercise” and Documentation Requirements

In early 2015, the Jordanian government began to require all Syrians living outside the camps to re-register with the Interior Ministry, a project called the “urban verification exercise.”[126] This requires Syrian refugees and non-refugees to go to a local police station, submit the required documents, and obtain new service cards that include biometric data. Such cards are required to access subsidized public healthcare and public schools.[127]

The verification exercise should allow refugees who have an asylum seeker certificate to regularize their status and obtain new service cards, even if they left the camps outside the bailout system. However, those who left the camps after July 2014 without being bailed out are ineligible.

Many other refugees who left the camps before July 2014 said they had avoided the reverification process because they could not pay the costs involved. Initially, the re-registration application obliged Syrians to pay for a health certificate from the Ministry of Health, and to present a rental agreement stamped by the local municipality and a copy of their landlord’s identity document.[128] These requirements were virtually impossible for many Syrians to meet. The health certificates cost 30 JD ($42) for each family member older than 12 years; most rental agreements were oral rather than written; and landlords who were behind on their taxes were hesitant to present their identification documents at police stations.[129] Jordan later lowered the cost of health certificates for Syrians to 5 JD ($7) per person, and allowed Syrians to present a UNHCR letter confirming their address in lieu of a lease agreement and the landlord’s identification document.[130]

The verification exercise also requires Syrian refugees to present official Syrian identification documents in order to re-register. Some refugees did not bring any documents with them.

In addition, from 2012 to 2014, Jordanian authorities retained around 219,000 such documents from Syrian refugees at “reception centers,” when they first entered the country, and stored them there.[131] Border authorities initially confiscated passports or other identity documents, but also retained marriage certificates and “family books,” which Syrian authorities issued to couples who registered their marriages, and to which the names of the married couple’s registered children would subsequently be added.[132] Syrians who were bailed out of refugee camps, or who are seeking to re-register under the verification exercise, may request UNHCR assistance to obtain their Syrian documents from the Jordanian authorities. In total, UNHCR and Jordan had returned 81,000 of these documents to families residing in the camps by the end of 2014.[133]

During a similar “re-verification” process for refugees in Zaatari camp in 2014, implementing agencies found that “about 35 percent of refugees’ documents have been misplaced by [Jordanian] authorities.”[134] It appears that many documents were eventually recovered; according to international humanitarian agency staff, as of April 2016, only around 930 Syrian documents had been deemed lost.[135]

Delays in returning documents to refugees has left some families unable to enroll children in public schools. Hassan, 34, left a Syrian army unit three months before the uprising began in 2011, and fled to Jordan in 2013. He tried to enroll his six-year-old daughter in first grade at a public school in Amman. The only school in his area said he had to present her Syrian identification documents to do so, “but we had left the documents in Zaatari camp, and then they were sent to Rabaa al Sarhan [the reception center].”[136]

Hassan said police failed to register the fact he had been bailed out of the camp, necessitating his return to the camp, then to Amman, to retrieve the family’s documents from two different police stations. “The problem is we’re now a month late to enroll her and the school says it has no space,” Hassan said.[137]

As of March 31, 2016, the Interior Ministry had issued about 319,647 new biometric service cards to registered Syrian asylum seekers in host communities, in addition to 22,623 cards issued to Syrian non-refugees, as a result of the urban verification exercise.[138] However, around 520,000 registered Syrian asylum seekers are living in host communities, according to UNHCR data, meaning that more than 40 percent of the population still did not have an updated service card more than 13 months after the policy requiring them was announced on February 15, 2015.[139]

Jordanian policy is that Syrians must provide a new service card to access government services including education and healthcare.[140] Jordan has not enforced this policy to date, and according to staff at humanitarian agencies and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), the Education Ministry had also pledged not to enforce this policy in the 2016-2017 school year.[141]

Address Requirements

Some refugees faced delays enrolling their children in school because they had moved after receiving a service card but could not update their registration and obtain new cards, or did not know how to do so, prolonging the time they had already been out of school.

Halima, 50, fled from Eastern Ghouta, Syria to Jordan in 2013. Her children had already missed a year of school in Syria due the conflict.[142] The family obtained UNHCR asylum seeker certificates, but then moved, and were unable to obtain new certificates or service cards valid in their new district from the Interior Ministry. As a result, her youngest son, Hassan, was only able to enroll in school in the fall of 2015, two years after coming to Jordan. “I visited so many schools, but they would not register him,” Halima said. “They would say, ‘If you’re Syrian we can’t let you in without an ID [i.e., a service card].’” She said that two schools in the area where they moved refused to enroll her children because they did not have service cards. Unable to attend school in Jordan, her three older children were working in construction and house-painting.[143]

Noura, 25, said that her family came from Eastern Ghouta in 2013 to Zaatari refugee camp, but left after 10 days without going through the bailout procedure. When she tried to enroll her 7-year-old daughter, Aya, in first grade in a United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA) school in Baqaa, a Palestinian refugee camp outside Amman, the school asked for a UNHCR asylum seeker certificate, a record of vaccinations, and an Interior Ministry service card, “but the thing they really cared about was the area. The problem is that the [service card] says ‘Amman,’ not ‘Baqaa’.”[144] With the help of a camp resident who “has connections,” Noura said, she was eventually able to enroll Aya, but said she was scared that Aya would not be able to re-enroll the following year because school officials told her they expected her to change her official residency. She was unaware of what steps she could take to do so.[145]

“Three Year Rule” and Inadequate Access to Informal Education

A Jordanian Ministry of Education regulation—commonly called the “three-year rule”—bars any child, Jordanian or Syrian, who is more than three years older than the grade level for children their age to enroll in formal schooling.[146]

Estimates of the number of Syrian school-aged children who were ineligible to enroll in public school for this reason range widely, from 60,000 in December 2013, to 77,000 children in June 2014.[147]

Jordanian authorities say the three-year rule is necessary to maintain the quality of classrooms. However, the regulation has excluded many Syrian children who had been out of school in Syria because their schools were closed or destroyed, or their families were internally displaced by the conflict, looking for work, or moving to lessen the burden on relatives who were hosting them.[148]

The number of Syrian refugee children in Jordan who were unable to enroll in school due to the conflict is unknown, but UN agencies report that one-quarter of the schools in Syria— 6,000 schools—have been destroyed or severely damaged; the conflict, which killed 10,000 children from 2011 to 2013, when the last verified figures were available, has left two million children in Syria unable to go to school.[149] One refugee family said that after their children had missed a year in school in Syria, the lack of available classroom spaces in Jordan had prevented them from enrolling their children in school for up to two years, raising the concern that the “three-year rule” could bar their re-enrollment.[150]

Jordan has accredited one international NGO, Questscope, to teach accelerated classes to children in host communities. But, without substantial donor support, access to accelerated programs for out-of-school children has been limited, and only a few thousand children, including Jordanians and Syrians, have accessed them to date.[151] In February 2016, USAID said it had partnered with Questscope to expand non-formal education to 28 new centers and enroll an additional 1,680 out-of-school children, train teachers (called “facilitators”), and strengthen programs at up to 115 centers.[152] The programs have not been available to children under 12 or over 15, or to any children barred from re-enrollment by the three-year rule. Some children who obtain an informal qualification equivalent to the 10th grade public school certificate are eligible to continue to secondary school, but only at home.[153]

At least three refugee families whom Human Rights Watch interviewed said their children were barred from enrolling in school due to the “three-year rule.” The total may be higher, but none of the families was aware of the details of the regulation. In addition, none was able to access the informal education programs required to re-enroll in formal education.

Shamsah, from a village near Aleppo, said that she tried to register her daughter Dou`a, 12, and her son Assad, 11, in lower grades after they fled to Jordan in 2014, so that the children could “catch up.” Dou`a had only completed grade 1 in Syria, and Assad had never completed a grade. School officials told their mother that the children were “too old” to be enrolled.[154] Speaking of Assad, she said:

Back in our village … Assad had allergies and asthma so he missed school a lot. When he came to Jordan he’d never completed a grade. Here I asked them to put him in second grade, but they said he was too big. He cries because he wants to go to school.[155]

Ahlam, 31, said her eldest daughter Lama, age 15, had been out of school for four years. When the family tried to enroll her in school in Jordan, Lama “had only done two months of grade seven in Syria, but she should’ve been in ninth grade according to her age.”[156] School directors first said Lama could not enroll because there was no room for more students; the following year, she had been out of school for too long. “She’s engaged to a man in Ein al-Basha” and will marry in 2016, her mother said. “She always wanted to finish school but since we came here everything changed.”[157]

In another family, Naima, a 14-year-old girl, had completed grade 6 in Syria but never been to school in Jordan, and the family had stopped trying to enroll her after school officials said she was “too old” to enroll.[158]

Local Non-Compliance and Documentation Requirements

In order to enroll in public schools, Jordan requires Syrian refugees to present their UNHCR asylum seeker certificates and Interior Ministry service cards. In addition, they may be required to prove that their children have been enrolled in school within the past three years, and students seeking to enroll in secondary school must show they have taken the grade 10 exam in Jordan or proof of equivalent education in Syria.[159]

However, some school directors have refused to allow Syrian families to enroll their children on the basis of other, unofficial criteria. Susan, 33, said that when she tried to enroll her three school-aged children in the 2014-2015 school year in Na`imeh, a town near Irbid, the school director told her “that there was a government decision that Jordanians don’t learn with Syrians.”[160] She tried again in January or February 2015, she said, “but the director said the Ministry of Education had rejected my application.”[161]

Leila, 33, from Eastern Ghouta, was able to present her Syrian identification documents and UNHCR asylum seeker certificate to school officials when she tried to enroll her 13-year-old daughter Bisan in the fall semester of 2013, but did not have her daughter’s official school certificate showing she had been enrolled in 5th grade in Syria.[162] On that basis, she said, the school director first rejected her enrollment outright, and then, in a subsequent meeting, offered to let her to enroll in grade 4. “The same director rejected my sister Khadija’s kids without explanation, too.” They ultimately enrolled in another school.[163]

In another case, officials at a school in Mafraq refused to enroll Hala, 7, in the fall semester of 2015 because they said they had “no room”; but when her mother tried again, “the school said her UNHCR certificate mistakenly lists her as born in 2009,” instead of 2008, her correct birthdate.[164] “The school told us she can register if there’s proof she’s old enough, but we had to fix the card with UNHCR first.” Adding to the errors, her Interior Ministry-issued service card lists her as born in 2005. Yet even if she were 6 years old, not 7, the girl should be eligible to enroll in school.[165]

Lack of Birth Certificates

Syrian asylum seekers may also face difficulties obtaining birth certificates for their children, without which they cannot obtain the Ministry of Interior service cards that are required to access subsidized healthcare, and will be needed to enroll the children in public school once they reach school age.[166] To obtain birth certificates, Syrian parents must apply to Jordan’s Civil Status Department, which usually requires them to present a valid Ministry of Interior service card as well as proof that the parents are married. Some parents lack valid service cards, for the reasons described above, while others cannot provide proof of marriage.[167]

Some couples who married in Syria fled without bringing the marriage certificates or “family books” issued to married couples by Syrian authorities. In other cases, Jordanian authorities confiscated these documents when the refugees entered. Other couples were married in Jordan but were unable to register their marriages there because they left refugee camps without being bailed out and therefore lacked valid identification documents. [168] And parents who had children in Syria but who fled before obtaining a Syrian birth certificate cannot obtain a Jordanian birth certificate. Parents who do not register their children’s birth within one year must open a court case to do so, which can be expensive, time-consuming, and requires the same documents.

UNHCR estimated in 2014 that up to 30 percent of Syrian refugee children in Jordan— where, as of March 2016, more than 108,000 Syrian children have been born since 2011— did not have birth certificates.[169] The lack of birth certificates could prevent tens of thousands of children from enrolling in school in coming years.[170]

According to international humanitarian agency staff, special committees comprising representatives of the Interior, Education, and Justice ministries, as well as security officials, meet weekly in cities around the country to resolve cases of Syrians who entered Jordan without documentation, or whose marriages or children were incorrectly registered.[171] In 96 percent of cases the special committees have resolved the problems, humanitarian staff said, but in total, are able to process only 35 cases per week.[172]

Trauma and Inadequate Mental Health Resources

A 2015 UN-coordinated survey that addressed the educational needs of Syrian refugee children with disabilities in Jordan found lack of physical accessibility, specialist educational care, and psychological effects of the Syria conflict were key barriers to education. Jordanian teachers identified lack of training to support children with disabilities as a key need.[173]

Many Syrian parents said their children had witnessed apparently traumatizing events in Syria before fleeing to Jordan, including in detention.[174] In some cases, these experiences led them not to enroll in school in Jordan.

Ahmad, 15, had already dropped out of school in Syria at age 9 to take care of his father’s small store when his father was detained, but had wanted to go back to school until experiences during the conflict “changed his personality,” his mother said.

He carried injured fighters, and dead bodies, and once he had to carry his cousin’s head. His father was arrested in 2011 and detained for a year and a half. I tried registering him in school [in Jordan] but he didn’t want to. He doesn’t even want to leave the house anymore.[175]

Maya, 12, is extremely self-conscious about the scar from a shrapnel wound that runs from her wrist to her finger, wets her bed at night, is not in school, and does not want to attend school, her mother said.[176] In one case, a Syrian father who lived near a Jordanian air force base described how an apparent military training exercise “terrified” his seven children, who refused to leave the house to go to school for several days.[177]

Humanitarian organizations including Mercy Corps, and UNICEF-supported Makani centers for children and youth have provided tens of thousands of refugees in Jordan with psychosocial support services in host communities and refugee camps—a significant improvement over international responses to the 2003 Iraqi refugee influx in Jordan.[178]

A 2015 UNICEF review of its psychosocial support response in Jordan found it had appropriately used the Minimum Standards for Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (MHPSS) in emergencies as a starting point and evaluation tool, but that support centers were overcrowded and should be open longer, staff lacked adequate training to deal with issues such as child labor and early marriage, and as a result, “almost all staff seemed to struggle with their intended role of identifying and addressing psychosocial or mental health needs.” Some staff felt more serious cases needing referral were sometimes missed.[179]

While greater access to sustained psychosocial support for Syrian children is needed, such interventions may be insufficient to counter the loss of self-sufficiency and hope resulting from work-permit restrictions.[180]

Some parents whose children were enrolled in school in Jordan said that traumatic experiences in Syria badly affected their ability to study and to function socially. Kunuz, 34, from Homs, said her son Mahmud, a nine-year-old in third grade at a public school, “had memorized the [Arabic] letters in Syria, he was a good student there, but now he can’t learn,” after the children’s neighbors were burned during an attack in their small village.[181] “He doesn’t want to go to school. If he gets homework and can’t do it he’s afraid he’ll get in trouble.” Mahmud’s father had been missing for three years and was presumed dead. The boy had received some psychosocial support from Terre Des Hommes, an NGO, but told a Human Rights Watch researcher: “I liked my school back in Syria.”[182]

There were no psychosocial support services to help Hana’s three children, who were struggling at their public school in Jordan after witnessing a neighbor’s house in Syria get blown up and subsequently fleeing from town to town:

[I]t fell on top of our house. It was a miracle we got out. All the boys fainted. We didn’t sleep all night, running away from the bombing.[183]

A teacher at a primary school in Zaatari camp said that he had received no training to deal with injured children—including one in a wheelchair and another who cannot see following eye surgery—and that he found it difficult to deal with “traumatized children, who share their emotions loudly and unpredictably, or are just silent in class.” One boy, he said, “is not present. You talk to him and he’s always looking far away.”[184]

Challenges Providing Quality Education

The large number of Syrian students is a part of the challenge of ensuring the quality of education. Syrian students fare much worse in school than Jordanian students.

A joint 2015 study of children aged 9 to 17 by the International Labour Organization (ILO) and Fafo, a Norwegian research foundation, found:

- Around 54 percent of Syrian children are enrolled in the formal school system, as opposed to 94 percent of Jordanian children in this age range.[185]

- Syrian students have less educational experience than Jordanian students.

A 2014 survey found that around 60 percent of Syrian refugees had not completed primary education, compared to 25 percent of Jordanians; while 42 percent of Jordanians had completed secondary education, only 16 percent of Syrian refugees had.[186] Jordanians were four times more likely than Syrian refugees to have pursued post-secondary education.[187]

School infrastructure varies widely but is often poor in both host communities and refugee camps. In Jordan’s refugee camps, the Education Ministry has established and accredited formal schools that teach a modified version of the Jordanian curriculum. The quality of school infrastructure in the camps varies widely. Human Rights Watch visited a school in the Emirati Jordanian refugee camp where classrooms had electricity and windows, and two schools in the Zaatari and Azraq refugee camps that had no electricity, lighting, heating, or cooling. In each camp, the same buildings were used as girls’ schools in the morning and boys’ schools in the afternoon.

Bassam, who teaches three different classes with a total of 120 students in Zaatari camp, said, “There’s no drinking water at school, no food, and no electricity,” which left classrooms exposed to desert heat in late spring and early fall, and very cold in winter.[188]

Some schools in refugee camps as well as host communities suffer overcrowding. Marwan, a 12-year-old student in fourth grade in Mafraq, is enrolled in the afternoon shift at a public school, where normally there are almost 30 children in his class, but “teachers sometimes combine their Arabic or science classes, so they teach us all together.”

When they combine the classes … the other children who come in have to sit on the floor, and some have to stand. It doesn’t happen all the time, maybe three days a week.[189]

He and his brother were not learning much, their mother said: “It’s as if they weren’t going to school.”[190] Teachers and administrators in some refugee camp schools described overcrowding of up to 50 students per class, and wide age ranges of students in each grade, which made it impossible to reach each child at the appropriate level of instruction.[191]

Children at schools operating two shifts receive fewer hours of instruction than children at other public schools operating on a regular schedule. Second shift classes in host communities and all classes in refugee camps, which are attended only by Syrian refugee children, offer fewer subjects than morning shift and single shift classes, which are attended by both Jordanian and Syrian children. The reduced class time was necessary to keep classes short enough to operate the double shift, but has resulted in a two-tier education system, with reduced quality for Syrian and Jordanian students in double shift schools, and for Syrian students attending afternoon shifts in particular. Bassam teaches grade 7 classes at an accredited public school in Zaatari camp. He described the differences between the curricula:

We teach English, Arabic, religion, history, math, physics, and science, but no chemistry or sports like they would in a normal school. In a normal school, each class would be 45 minutes long, but here, it’s 30 minutes. Normally you’d have a 5-minute break between classes, so the teachers can change, plus a 30-minute lunch break. Here, there’s no breaks. Students eat in class. Really you only get 25 minutes per class.[192]

Bassam and an administrative official at his school said that they were not aware of any visits from external quality monitors or observers.[193] Bassam said he had not received “any kind of training” before he began teaching:

The Education Ministry published an ad saying they need teachers in the camps. When I applied, they only asked for my ID [identification document] and my university certificate. Then suddenly they called me and said “You can go to the camp now.” I was shocked. I had no time to prepare a teaching plan or even to put a cover on my book. I didn’t even know where the school was.[194]