A painted wall outside a women’s organization in Nicaragua names and shames, a kind of brick-and-mortar #MeToo. Inscriptions on the wall in front of the Colectivo de Mujeres de Matagalpa tell the stories of violence against women: names of the accused, descriptions of attacks, and more. In a country with high levels of gender-based violence, civil society repression, and decreasing funding for women’s groups, this is risky.

But the Nicaraguan organization is brave. The work of its women members illustrates the local action at the heart of global movements for women’s rights, gender equality, and freedom from violence. These movements are strong, but embattled.

Today, on the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women, we look back at the ups and downs of 2017.

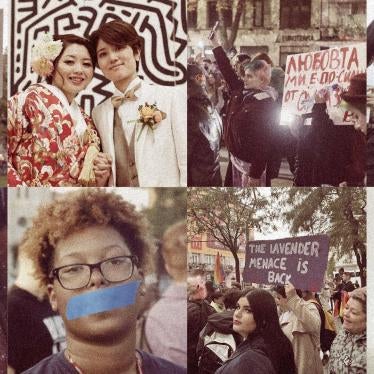

The Women’s Marches on all continents spurred some five million people to take to the street to demand equality and freedom from violence. Millions posted #MeToo stories of sexual harassment and abuse, resulting in high-profile apologies, resignations, and calls for legislative reform. Activists and movements united to fight intersecting forms of discrimination. From stalwart feminist leaders to newly galvanized activists, people stormed the streets and halls of power to demand change.

But there were also grounds for despair in 2017.

In Burma, security forces committed widespread rape of women and girls as part of a campaign of ethnic cleansing against Rohingya Muslims, which forced more than 600,000 Rohingya to flee to Bangladesh. Survivors reported symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder or depression, untreated injuries, including vaginal tears and bleeding, and infections. The government dismissed these violations in official investigations, and rarely holds perpetrators—civilians or soldiers—accountable.

In the Central African Republic, armed groups continued to use rape and sexual slavery as a tactic of war. Commanders tolerated widespread sexual violence by their forces and, in some cases, appear to have ordered it or committed it themselves. While the number of allegations has decreased, reports of sexual exploitation and abuse by peacekeepers against women and children continued to surface.

In Brazil, authorities fail to investigate or prosecute thousands of domestic violence cases each year, leaving women at further risk of abuse. Police also fail to monitor thousands of protection orders issued by judges to victims.

In Russia, where, domestic violence kills 12,000 women per year, the government decriminalized acts of domestic violence that don’t cause severe injuries. A brutal campaign against LGBT people swept through Chechnya, with law enforcement and security agents torturing and humiliating individuals suspected of being gay. LGBT people are also in danger of so-called “honor killings” by their own relatives for supposedly tarnishing family honor, a vile traditional practice openly encouraged by local authorities.

In Algeria, police inaction, insufficient shelter space, and ineffective investigation and prosecution left women who are domestic violence survivors at risk of further mistreatment, despite a recent law criminalizing spousal abuse.

In India, five years after the gang rape and death of a student in Delhi spurred reforms, girls and women survivors of sexual violence and rape continue to face significant barriers in access to justice and support services.

In all these cases, and in other countries around the world, civil society groups demanded accountability and reform.

In some cases, they saw progress. For example, several governments in the Middle East and North Africa repealed penal code provisions that allowed rapists to escape punishment by marrying their victims. Tunisia passed a law improving protections for domestic violence survivors and criminalizing sexual harassment in public spaces. Kyrgyzstan adopted a new domestic violence law to improve protections and strengthen police and judicial response. The State of New York adopted a new law to dramatically reduce child marriage, which is correlated with domestic violence and other harms. The UN issued new global guidance on combatting gender-based violence against women.

In other cases, activists saw backsliding or recalcitrance, and some faced threats, arrests, and clamp-downs. This repression jeopardizes broader civil society efforts to push governments to overcome gender inequality, at a time when this is sorely needed. The World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report 2017 said that the parity gap in across health, education, politics and the workplace widened this year.

Some say that this year will be a turning point for women’s rights and gender equality. The evidence from the year 2017 is that a turning point can’t come soon enough for survivors, and for the movements pushing for change.