Summary

“Salwa” is a 39-year-old woman from Annaba with two children and a long history of abuse by her husband. She told Human Rights Watch that he started beating her from the early days of their marriage in 2006. She said she endured this treatment for years and never went to the police because she was too afraid of him. In September 2011, he hung her by the arms to a bar in the ceiling of their house with an iron wire and stripped her naked. He took a broom and beat her with it. He then lacerated her breasts with scissors, she said.

Bleeding and screaming, Salwa fainted. When she woke up, she discovered that her sister-in-law had come in. She freed Salwa from the wire, gave her something to wear, opened the door of the house, and told her to flee. She ran until she came to a hospital. The police guarding the hospital escorted her inside. At the emergency unit, they gave her first aid care but told her she could not stay. The police at the hospital took her to a police station. She had visible bruises, blood on her clothes, and her face was swollen from his beatings. She filed a complaint and accepted the police’s offer to take her to a shelter. They first took her to a state shelter for homeless people. Finding the shelter “overcrowded, not clean,” Salwa went to another in Annaba, one run by a nongovernmental organization.

When she felt physically able to leave the shelter, she went to the police to inquire about her complaint. They told her, “we called your husband, he said you fell and that is why you are bruised.” The police did not conduct any further investigation, such as summoning her husband for interrogation at the police station or arresting him, Salwa said.

With the help of the association running the shelter, she hired a lawyer and filed another complaint against her husband for assault. She said that a court eventually sentenced him to a fine and six months’ suspended imprisonment.

She filed for divorce twice, each time on the grounds of physical harm. The first time, in 2012, the court rejected her request for divorce and ordered her to return to the conjugal home. A year later, the court granted her request for divorce and ordered her husband to pay alimony. When he did not comply, she filed a complaint against him. She said the court sentenced him to six months in prison and a fine, but he went into hiding and the police said they could not find him.

As of April 2016, Salwa was still living in the shelter with no other place to go, bitter about the state’s response to her ordeal.

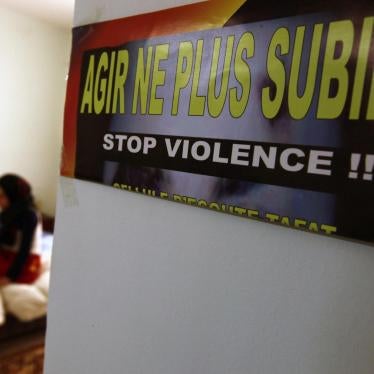

Salwa’s experience illustrates some of the ways that Algerian authorities fail to provide adequate support, protection, and remedies to survivors of domestic violence.

Lack of due diligence from the police in conducting initial investigations of the abuse, lack of enforcement of sentences, and economic dependence on the abusers combine to present domestic violence survivors in Algeria with an uphill struggle.

Human Rights Watch documented cases of both physical and psychological violence. Women told Human Rights Watch about instances in which perpetrators: shoved them; broke their teeth or limbs; caused concussions and skull fractures; beat them with belts and other objects; beat them while pregnant; threatened to kill them; and verbally humiliated them.

Police figures show that more than 8,000 cases of violence against women were recorded in 2016, 50 percent of which are domestic violence cases. The last survey by the State Ministry for the Family and the Status of Women, dating to 2006, revealed that 9.4 percent of Algerian women between the ages of 19 and 64 reported being victims of physical violence often or daily within the family.

Domestic violence survivors can find themselves trapped not only because of economic dependence on their abusers but also because of social barriers which include pressure to preserve the family at all costs, stigma, and shame for the family if women leave or report abuse.

Such barriers are compounded by the failures of the Algerian government to adequately prevent domestic violence, protect survivors, and create a comprehensive system for the prosecution of perpetrators. The shortcomings of the Algerian government’s response to the problem include a lack of services for survivors of domestic violence, particularly shelters; a lack of measures for prevention of violence such as use of educational curricula to modify discriminatory social and cultural patterns of behavior as well as derogatory gender stereotypes; insufficient protection from abusers; and an inadequate response from law enforcement.

Service provision for survivors of domestic violence, including shelter, psychosocial care, and facilitation of access to justice, lies almost entirely in the hands of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), most of which receive no state support.

There are also important gaps in Algeria’s legal framework for responding to domestic violence. Until December 2015, domestic violence was not a specific criminal offense. Instead, physical violence could only be prosecuted under the general criminal provisions related to assault, categorized on the basis of the severity of the injuries. When the wounds healed within 15 days, as was often the case, the prosecutor’s office treated the assaults as minor offenses.

In December 2015, parliament amended the penal code to address gaps on criminalization of violence against women by criminalizing some forms of domestic violence. Law no. 15-19 makes assault against a spouse or ex-spouse punishable by up to 20 years in prison, depending on the victim’s injuries, and by a life sentence if the attack results in death. It also expanded the scope of sexual harassment, strengthened penalties for it, and criminalized harassment in public spaces.

While these amendments are an important step forward, the law contains several shortcomings, and comprehensive legislation is still needed for an effective and coordinated response to violence against women. The parliament should seek to address this through further legislation.

First, the 2015 law offers the possibility for the offender to escape punishment or benefit from a reduced sentence if the victim pardons the perpetrator. This increases the victim’s vulnerability to social pressure to pardon her abuser and might dissuade her from seeking court remedies for domestic violence.

Second, the definition of domestic violence does not explicitly mention marital rape, a form of abuse that woman across the world commonly face. In addition, the scope of the definition of domestic violence does not include all individuals. It considers spouses and ex-spouses as the only potential perpetrators, to the exclusion of other relatives and persons. For example, the provisions on assault, psychological, and economic violence do not apply to individuals in intimate non-marital relationships, individuals with familial ties to one another, or members of the same household.

Third, the law relies excessively on assessments of physical incapacitation to determine the level of sentencing, without offering guidelines for forensic doctors on how to determine incapacitation in domestic violence cases. In Algeria, as in many other countries, a doctor’s report following examination of an injured patient includes a recommended number of days of partial or full rest, based on an assessment of the person’s incapacitation and the time needed for recovery. The law also ignores that harm resulting from domestic violence may be the result of several incidents of beatings that cannot be assessed in a single forensic examination.

Human Rights Watch interviewed 20 victims who reported various injuries, ranging from concussions to permanent disabilities. Even in the most severe cases, where the victim had permanent injuries from the beatings, the forensic doctors gave a medical certificate of less than 15 days’ convalescence, which ruled out the imposition of heavier sentences on the perpetrators.

“Hassiba” who suffers from paralysis of her left arm and leg, as a Human Rights Watch researcher observed, said her disability was due to a brain injury after her husband threw a chair at her head. However, the courts ruled only for a two-month prison sentence and a fine of 8,000 Algerian Dinars (US$73) because they relied on the report by the forensic doctor who examined her injuries following the abuse and recorded only 13 days of incapacitation, rather than a sentence of 10-20 years for causing a permanent disability.

Fourth, the law lacks any provision for protective orders (also known as restraining orders), considered by the United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women, or UN Women, to be among the most effective legal remedies for domestic violence survivors. Protective orders are measures aiming at protecting survivors of domestic violence from further abuse, for example by prohibiting the alleged abuser from calling the victim, ordering him to stay a certain distance from the victim, or requiring the alleged abuser to move out of a home shared with the victim.

Finally, the law lacks guidelines on how law enforcement should handle domestic violence cases. One of the major obstacles women encounter to filing complaints is the dismissive attitude police have towards victims of domestic violence. Of the 20 cases documented by Human Rights Watch, 15 women said that the police discouraged them, in various ways, from filing a complaint.

Some survivors said that even in cases where police registered their complaints, they felt there was inadequate or even no follow-up investigation by police or prosecutorial authorities, such as making an onsite visit and identifying and questioning witnesses.

There is a growing trend to combat domestic violence through legislation in the Middle East and North Africa. Several countries or autonomous regions in the Middle East and North Africa region have introduced some form of domestic violence legislation or regulation, including Bahrain, Kurdistan Region of Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, and Saudi Arabia. These laws vary in the degree to which they comply with international standards.

Algeria’s neighboring countries, Morocco and Tunisia, are also considering draft legislation on domestic violence that go further than Algeria’s law on criminalizing forms of domestic violence such as by providing protection mechanisms and other services for survivors.

Algeria should ensure that its legislation on domestic violence is comprehensive and in line with international standards. Without such measures, Algeria will continue to put women and girls’ safety, and their lives, at risk.

Key Recommendations

To the Algerian Parliament

- Amend Law 15-19 by removing explicit references that provide for termination of prosecution, cancellation, or reduction of any court-imposed punishment if the victim pardons the offender.

- Adopt comprehensive legislation fully criminalizing domestic violence, establishing services and other assistance for survivors, providing for prevention and protection measures, such as emergency and long-term protection orders, and setting out duties for law enforcement.

- Include rape and sexual violence between current and former intimate partners as a form of domestic violence.

To the Algerian Government

- Establish a national database on violence against women which includes information on domestic violence showing the number of complaints received, investigations undertaken, prosecutions mounted, convictions obtained, and sentences imposed on perpetrators.

To the Ministry of Interior

- Establish a police response protocol to domestic violence whereby police should be directed to accept and register domestic violence complaints and inform domestic violence survivors of their rights with regards to protection, prosecution, and redress.

- Ensure that specialized training on domestic violence is included in the curriculum of the police academy.

To the Ministry of National Solidarity, Family and Women’s Conditions

- Conduct public awareness campaigns on the criminalization of domestic violence and combat social attitudes that involve normalizing domestic violence, blaming victims, and stigmatizing survivors.

To Algeria’s International Partners, including the European Union and its Member States

- Raise violence against women and domestic violence in Algeria as a key area of concern in bilateral and multilateral dialogues with Algerian authorities and urge the government of Algeria to address such violence through reforms in the social service, law enforcement, and judicial sectors.

- Provide funding to support shelters for survivors of domestic violence, as well as for other key services, including psychosocial counseling and legal assistance.

Methodology

This report documents the government of Algeria’s response to domestic violence and the lack of adequate services, protection, and legal remedies for victims. It is based on Human Rights Watch’s research conducted in June 2015 and April 2016. Efforts were made to interview survivors of domestic violence from different parts of the country and from different socioeconomic backgrounds. Human Rights Watch interviewed 20 survivors of domestic violence. In addition, we interviewed 20 other people, including representatives of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) working on domestic violence cases or service providers for survivors, lawyers, psychologists, and European Union representatives.

Human Rights Watch identified survivors with the assistance of local service providers, NGOs, and women’s rights activists.

Human Rights Watch informed all interviewees of the purpose of the interviews, as well as how information collected would be used, and received oral consent before conducting the interview. Survivors were also informed of their right to stop or pause the interview at any time.

We gathered additional information from published sources, including government data, United Nations documents, academic research, and news media.

Human Rights Watch wrote a letter, annexed to this report, to the head of government on May 25, 2016, requesting information for incorporation into this report and meetings with officials who could discuss relevant policies. No responses had been received at time of writing.

All survivors’ names are pseudonyms and some identifying details have been withheld for their security and privacy.

I. Background

“The laws and policies [of Algeria] have not been able to remove all obstacles to de jure and/or de facto discrimination and to fully transform entrenched attitudes and stereotypes that relegate women to a subordinate role. Patriarchal mentalities, challenges in the areas of the interpretation and implementation of the law, the use of mediation to solve incidents of violence, the absence of verifiable statistics on the prevalence of violence, and the absence of effective cooperative and collaborative partnerships between civil society and the state heighten women’s vulnerability to violence.”

- 2011 report of the United Nations Special Rapporteur on violence against women.[1]

Data on Domestic Violence Prevalence

To Human Rights Watch’s knowledge, there are no recent national surveys about the prevalence of domestic violence in Algeria. The last survey by the State Ministry for the Family and the Status of Women,[2] dating to 2006, revealed that 9.4 percent of Algerian women aged between 19 and 64 years reported being victims of physical violence often or daily within the family.[3] The study also found that marital rape existed, and that 10.9 percent of women admitted having been subjected to forced sexual relationships by their intimate partners.

A 2013 study conducted by Balsam, a network of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) working on domestic violence across Algeria, found that, among the 1,000 women who sought support from the various associations forming part of the Balsam network between 2011 and 2013, higher levels of violence were found among married women than among unmarried women, especially if they do not work outside of their homes. The report found that physical and psychological violence were the most widely reported forms of abuse. Twenty-seven percent of the 1,000 women said they were victims of sexual violence.[4] The same study showed that the perpetrators of domestic violence came from various social backgrounds.

In her 2011 report following a mission to Algeria, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on violence against women, its causes and consequences, referred to a General Directorate for National Security report, which recorded 6,748 cases of violence against women from January to September 2011. The Special Rapporteur called this a “very low figure compared to the prevalence rates found in the 2006 national survey and also recent studies by support centers operated by civil society organizations.”[5] The General Directorate for National Security reported 8,000 cases of violence against women in in the first six months of 2016, 50 percent of which were domestic violence.[6]

The Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the UN Secretariat’s “Guidelines for Producing Statistics on Violence against Women” says: “Without a full understanding of the scope, dimensions and correlates of violence against women, it is not possible to design appropriate responses aimed at properly addressing or preventing such violence at any level of government or civil society.”[7]

National Strategy

In 2003, authorities launched a three year-long consultation with civil society, governmental agencies, and UN bodies to develop a “National Strategy on Combatting Violence against Women.”[8] The strategy, adopted on 2007, brought together several stakeholders that deal with domestic violence survivors, including the Ministries of Justice, Health, National Solidarity, Family, and Women’s Conditions, as well as the police, the gendarmerie, and women’s rights groups.

The national strategy recommended, among other things, the establishment of centers for listening to and taking care of the victims of violence. It also called for the creation of new mechanisms for the registration of complaints by women. The document pressed the government to establish, within the police force and the Gendarmerie Nationale (the police force that operates mainly outside of urban areas), special units that can refer victims to longer-term shelters. It also stressed the need to develop, in a participatory process, a standard protocol outlining the manner in which various state institutions should receive, listen to, support, and orient victims of gender-based violence and the manner in which female officers should be trained to handle such violence. The strategy also recommended that authorities adopt a protocol for forensic doctors on documenting domestic violence. While welcoming these recommendations, Human Rights Watch is unable to confirm that the authorities implemented any such steps.[9]

The letter that Human Rights Watch sent on May 25, 2016 to Algeria’s head of government requested information about the existence of specialized domestic violence units, domestic violence personnel in the police force, and protocols on handling domestic violence cases. The head of government had not replied to Human Rights Watch’s letter at time of writing.

According to the Balsam 2013 report and to service providers who spoke to Human Rights Watch, the General Division of National Security (Direction Générale de la Sécurité Nationale, or DGSN) created a special bureau for the protection of children and women victims of domestic violence.[10] Human Rights Watch was not able to verify this information, and the government did not respond to our questions about it.[11]

Positive Legal Reforms

Algeria has undertaken a number of legal reforms that promote women’s rights. In 2005, following campaigning by women’s rights groups, the parliament passed two laws favorable to women’s rights. The first is the amended nationality code to allow Algerian women with foreign spouses to pass on their nationality to their children and to their foreign husbands. [12] The second is the amended family code by increasing women’s access to divorce and custody of children. While many of the family code’s provisions remain discriminatory, the authorities removed the provision that stated: “The duty of the wife is to obey her husband.”[13] (See chapter VI on Algeria’s Legal Framework Compared to International Legal Obligations).

Algeria’s constitution enshrines the principle of non-discrimination on the basis of sex and requires the state to take positive action to ensure equality of rights and duties of all citizens, men and women, “by removing the obstacles that hinder the progress of human beings and impede the effective participation of all in political, economic, social and cultural life.”[14] In March 2016, the parliament amended the constitution by adding an article stating “the state works to attain parity between women and men in the job market” and “encourages the promotion of women in positions of responsibility in public institutions and in businesses.”[15]

Algerian laws contained no specific provisions on domestic violence until December 10, 2015, when the parliament adopted several amendments to the penal code that criminalized some forms of domestic violence and stipulated heavy sentences for it. The law also criminalized harassment in public spaces and strengthened penalties for sexual harassment. The amendments, known as Law no.15-19, came into force on December 30, 2015.[16] While the law was a welcomed step in recognizing and criminalizing domestic violence in some forms, it failed to fully criminalize domestic violence, including by not specifically criminalizing marital rape. Additionally, Algeria’s legal framework continues to lack the comprehensive legal measures needed to prevent domestic violence, assist survivors, and prosecute offenders (see chapter VI).

The following chapters show how women face barriers in accessing services and in ensuring that their abusers are held accountable. Various measures, including further legal reform, is needed to lift these barriers.

II. Social Barriers to Accessing Help

Social and economic barriers that prevent survivors of domestic violence from seeking assistance, protection, and justice include pressure to maintain the family at all costs, economic dependence on husbands, and stigma and shame if a woman leaves her abusive spouse.

Yasmina Boumerdassi, an Algiers lawyer specializing in family affairs, told Human Rights Watch that she has handled about a hundred cases involving domestic violence. She said in 90 percent of these cases, women victims drop their complaints and the prosecutors usually don’t pursue prosecutions after the women abandon their complaints.

She said: “They are afraid to be rejected by the family. They might ask for divorce, after long years of physical abuse, but they rarely go to court to file complaints against their husbands.”[17]

Another Oran-based lawyer, Tata Benhamed, said that between the time when a woman files a complaint and the moment she receives a summons from the prosecutor for the first interview, a wait that can last several months, many women become discouraged and abandon their complaint. Family members might pressure them by saying the complaint risks breaking apart their families, sending the father of her children to prison, destabilizing them, and bringing shame on the extended families.

Benhamed said that in 90 percent of the cases she followed, women dropped their complaint after they filed one with the police, when the complaint reached the prosecutor.[18]

Social Stigma and Family Rejection

Survivors, service providers, lawyers, and psychologists interviewed by Human Rights Watch spoke overwhelmingly of a social atmosphere that contributes to tolerance of domestic violence and silences victims. Authorities conducted a Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) with the UN International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) and the UN Population Fund (UNFPA) in 2012-2013 to gauge attitudes towards domestic violence.[19] The survey, conducted in 2012-2013, of 38,547 women across the country aged 15 to 49 years, found that 59% of them believe that a husband has “the right to beat his wife” for one or more of various reasons, including: if she goes out without his permission; neglects the children; argues with him; burns the food; shows disrespect for his parents; or refuses to give him her salary or to quit her job.

Lamia, 18, fled her family house in Tizi Ouzou in January 2016 because her father was beating her. She said that he did the same to her mother for years, before her mother decided to leave him. Lamia blamed her mother for leaving the family house:

In the Kabylie region, it is a shame to leave the house. Whatever the man does, it is the woman who is to be blamed. It is the man’s right to beat his wife.[20]

A director of an NGO shelter in Algiers said, “it is typical that their families tell women, ‘Be patient with your husband, accept the violence and stay quiet.’” The majority of the women that her shelter hosts felt guilty because their families had rejected them, she said.[21]

Several women who attempted to leave abusive relationships told Human Rights Watch that their families and the family of their spouse had encouraged them to return and reconcile, even when they had suffered serious injury.

Hasna, now 31 years old and the mother of four children, married at the age of 21 and lived with her husband and his parents in Oran. She stopped working, and after a year of marriage, she gave birth to their first daughter. She said that her husband repeatedly grabbed and pulled her by her hair, shoved her to the ground and beat her on her arms and stomach, even when she was pregnant.[22]

I felt alone. My father, each time I complained to him, said “Ma’alesh (it doesn’t matter), everything is maktoub (destiny), this is your husband, the father of your kids. Your destiny is to stay with him.”

She said she left him after ten years of abuse.

Hassiba, 55, with one daughter, comes from a poor family in Mascara, a town 100 km southeast of Oran. She dropped out of school at 12 and worked in a bakery in Oran. She married at the age of 40 to a man who forced her to quit her job. She said he started beating her two months after they married. He threw objects at her and slapped her on the face. When she told her father, he said, “Be patient with him, maybe he will change.”[23] After eight years of abuse, Hassiba left and divorced him.

Economic Dependence on Abusers

Many victims told Human Rights Watch that they remained in violent relationships in part because of their reliance on their husbands or their families for food and shelter. At least five out of the 20 women we interviewed had jobs before marriage but quit them, either under pressure from the husband or because they had to take care of the children.

Isolation can reinforce dependence on abusers. Some women reported that their spouses or in-laws controlled their movement and refused to let them work outside the home or contact their own families.

Hanan, now 55, married when she was 22 years old. Her parents initially opposed the marriage but relented when she insisted. She used to work in a pharmacy in Oran. When she got married, she obeyed the demand of her husband, who she said was very religious, to quit her job and wear the hijab. She said he also started to slowly isolate her, at first not allowing her to see her extended family, then to attend weddings or even funerals of friends and family. Hanan said that her husband started beating her several months after they married, even when she was pregnant. He slapped her on the face several times. She said she didn’t tell her parents because she was too ashamed and wanted to hide her ordeal.[24]

Several of the women interviewed by Human Rights Watch described a long history of family violence. They said they had experienced abuse at the hands of their parents or stepparents and/or came from broken homes. This left them even more vulnerable and with fewer relatives to whom they could turn to.

Jamila, a 44-year-old mother of five, came from a working-class family. Her parents died when she was young. She stopped her studies and at 16 married a man she loved. She gave birth to a disabled boy and her husband developed tuberculosis. After recovering, he started drinking heavily. She said he then met another woman and started beating her to force her to allow him to marry a second wife. When she refused, he shoved her and kicked her. She did not go to the police. “I had nowhere to go,” she said. “My parents were dead, I don’t have a family. I didn’t want to lose my kids and break the family ties.”[25]

On January 4, 2015, the Algerian parliament adopted Law no.15-01 creating a maintenance fund for divorced women supporting children.[26] The law stipulates that authorities will pay maintenance for children when there is a total or partial incapacity or failure by the husband to pay it. The law puts the onus on the person having guardianship of the children to first to file a complaint with the family court judge, providing documentation to prove the nonpayment of maintenance. The judge shall rule within five days on the nonpayment and then notify both parties, who have two days to appeal. The judge makes the final decision in three days. The relevant authorities are then to implement the decision and send the maintenance payment through bank or postal transfer to the beneficiary within 25 days. The fund will be financed by the state budget. The 2015 budget law created a new account number (302-142) in the national treasury of the state dedicated to the maintenance fund. The Minister of National Solidarity, Family and Women’s Conditions is the chief authorizing officer for the fund; the director of social affairs and solidarity at the wilayas (governorates) is the secondary authorizing officer.[27]

Human Rights Watch interviewed nine women victims of domestic violence who faced financial hardships after they finally decided to leave their husbands and the court gave them guardianship of their children. They said that they did not know about the maintenance fund. Others knew about it but had not yet attempted to file for assistance under its provisions.[28]

III. Lack of Shelter and Services for Domestic Violence Survivors

While women are left isolated and financially dependent on their abusers, many also said they did not know where to go for help, including shelters available to them.

Situation of State-Run Shelters

Human Rights Watch was not able to access state-run shelters in Algeria. The organization sent a letter on October 30, 2014 to the Algerian government, asking to meet to discuss domestic violence legislation and policies (see Annex I). Human Rights Watch sent another letter to the government on May 25, 2016, asking about the number of shelters available for domestic violence survivors and the level of funding they receive from the government (see Annex II). At time of writing, Human Rights Watch has received no answer to either letter.

The Special Rapporteur on violence against women, who visited Algeria in November 2010, noted that that there are only two state-run shelters specialized for women victims of violence, in Bou Ismaïl in the governorate of Tipasa and Tlemcen, and that both had limited capacity.[29] She further reported that in the absence of sufficient shelters, police and social services officials direct women fleeing violence to Dar al-Rahma [charitable houses] institutions, which accommodate a wide range of persons in need of state support, including the homeless and mentally and physically disabled persons.[30] The Ministry of National Solidarity, Family and Women’s Conditions published on its website a list of nine Dar al-Rahma [charitable house] institutions across the country.[31]

The state-run shelters for women victims of violence are regulated by a decree, dating back to 2004, which specifies their mandate, organization, and regulation.[32] The decree states that the shelters should provide for the temporary accommodation and medical-socio-psychological care of girls and women victims of violence and in distress. Admission to these centers depends on a decision from the governor or referral by security services.

According to the state’s report to the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, which monitors compliance with the Convention for the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), the National Shelter for Women Victims of Violence and Women in Distress in Bou Ismaïl has a capacity of 40 beds, and “has been undergoing extensions to increase its capacity to 100. The project is nearing completion, and the establishment is currently being equipped.”[33] The report states that in 2011, 15,280 women and girls went through the center and received psychological, legal, and social assistance. The report states that the total budget for the center in 2011 is 49,268.000 Algerian Dinars (US$449,166).

Human Rights Watch did not interview women who stayed in the shelters dedicated to hosting women victims of violence. However, we did interview one woman, Manal, who stayed for weeks in one of the state-run Dar al-Rahma institutions in Algiers, which, as noted, are not tailored specifically for the needs of survivors of domestic violence. While there is no evidence that Manal’s account necessarily represents conditions at such shelters nationwide, this interview provides a glimpse of the treatment that some women victims of violence face in such institutions.

Manal is 31 years old and lives in an NGO-run shelter in Algiers. She left her companion after he beat her on her abdomen when she was pregnant but went back to live with him because she had nowhere else to go, she said.[34] In June 2013, she left the house with her baby at night. She said she was walking along the street and did not know where to go, when a police car approached her. Police officials asked her what she was doing at night on the street, and she told them she had nowhere to go. They took her to a Dar al-Rahma facility for women, in a commune in Algiers. She described the conditions in the center as “horrible”:

As soon as I entered the place, the shelter staff asked me to take off all my clothes, even my underwear, and they kept me naked in a room for one hour. I felt humiliated. Then they gave me a uniform. They took my cell phone. I didn’t have the right to leave the shelter, even during the day. I felt as if I was in a prison.

She said there were around 50 women staying in the shelter for various reasons. There was no separate section for victims of domestic violence. She said that she saw, several times, the shelter personnel beat residents, especially those who had mental health problems or physical disabilities. One time she saw a staff member slapping a woman with physical disabilities because she had urinated in her pants. The shelter staff were rude and would often scream at the residents, she said. She also said that she asked several times for a diaper for her baby but they gave it to her hours later, while her baby cried the entire time. She also said that the shelter provided its residents with no training, instruction, or other recreational activities. Instead they made the women spend their days cleaning the rooms.

Situation of Private Shelters and Service Providers

Several service providers and women’s rights activists told Human Rights Watch that the government provides little in the way of services for survivors of domestic violence, relying on NGOs to fill the gap. They said that almost none of these services provided by NGOs receive government funding or material support and several said that these NGOs struggle to provide services.[35] While the UN Handbook for Legislation on Violence against Women advises that where possible, services should be “run by independent and experienced women’s non-governmental organizations providing gender-specific, empowering and comprehensive support to women survivors of violence, based on feminist principles,” it also notes the important role that the government can play in establishing and funding such services.[36]

Balsam, a network of NGOs working on domestic violence, listed in its 2013 report nine associations that have a counseling center, where women can obtain preliminary legal and psychological advice.[37] They listed three associations running private shelters, two in Algiers and one in Annaba.

Human Rights Watch visited shelters run by women’s rights associations that accept victims of domestic violence in Algiers and in Annaba. Human Rights Watch also visited two centers providing legal and psychological support for women. Largely dependent on donor support, these centers are scarce, underfunded, and concentrated in urban areas. In all these centers, women are usually allowed to stay for several months, together with their children. The multi-service shelters provide legal advice, psychological counseling, and training and educational opportunities.[38] The NGOs running the shelters told Human Rights Watch that women reach the shelter by various means; some come on their own, while the police bring others when they find them wandering the streets or when women file a complaint of domestic violence and say they have nowhere to go. Some learned about the shelters from public awareness campaigns run by the NGOs on state television and radio.

Human Rights Watch spoke with several survivors of domestic violence in these centers. Everyone praised the refuge, help, and support they received. Several told Human Rights Watch that their stay helped them to feel secure and confident enough to file a criminal complaint or apply for a divorce.

Several UN bodies including UN Women, the UN General Assembly, CEDAW, and the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR), have called on states parties to assist and protect domestic violence survivors, including by ensuring that they have timely access to shelter, health services, legal advice, hotlines, and other forms of support.[39]

The UN Handbook for Legislation on Violence against Women recommends that states introduce legal reform that mandates such support and services, and that states ensure funding for them. There are also minimum standards recommended by the UN on the level of some services, such as at least one shelter/refuge place for survivors of domestic violence for every 10,000 inhabitants, “providing safe emergency accommodation, qualified counselling and assistance in finding long-term accommodation.”[40] Algeria’s Law no. 15-19 does not detail any measures relating to shelter or other assistance for survivors of domestic violence.

Following her visit to Algeria in 2006, the then-UN Special Rapporteur on violence against women recommended that Algeria “strengthen institutional infrastructure for the effective protection of women from violence,” including by “ensuring adequate resources to improve existing infrastructure supporting a wide range of vulnerable persons, and creating new centers that provide similar specialized integrated services to victims of gender-based violence.”[41]

The UN Handbook for Legislation on Violence against Women recommends that survivors have access to financial assistance, such as through trust funds or social assistance programs.[42] Finally, the UN emphasizes the importance of coordination and referrals between agencies responding to domestic violence, and recommends that legislation set out a coordination framework.

IV. Police Response to Domestic Violence

The police are usually the first contact that the victims of domestic violence have with state institutions. Under the Algerian Code of Criminal Procedures, the judicial police, under the supervision of the public prosecutor, is in charge of establishing violations of the penal code, gathering evidence and identifying the culprits, until the decision to open an investigation into the case is made by the prosecutor or the investigative judge.[43] Once such an investigation has been opened, the police are required to act as the agent of the investigating jurisdictions and to comply with their instructions.[44]

In 15 of the 20 cases Human Rights Watch examined, the dismissive attitude of the police constituted an obstacle to filing complaints. In these cases, the women said that the police discouraged them, in various ways, from filing a complaint, or that they seemed to conduct little follow-up, if any, after registering their complaints. Neither the police nor prosecutors made onsite visits to identify and interview witnesses, including neighbors who in several cases intervened and helped the women. Such accounts suggest a need for legislation or policies that spell out the way such complaints should be handled.

Salwa, whose story appears at the start of this report, had endured years of mistreatment by her husband. She said following the last bout of violence in 2011, in which he lacerated her breasts, she ran to a hospital, where members of the police guarding the hospital took her inside. At the emergency unit, they gave her first aid but told her she could not stay at the hospital. They referred her to the hospital’s forensic doctor, who wrote a medical certificate prescribing 14 days of rest for her injuries but did not advise her to go to the police, she said.

Not knowing where to go, Salwa returned to the police at the hospital, who took her to the police station downtown. She said she had visible bruises and her face was swollen from the beatings. The police downtown recorded her complaint and then took her to an NGO-run Dar al-Rahma.[45] She described the conditions there as “very bad” and said she left the shelter and returned to the police. They took her to another NGO-run shelter, Dar al-Insania [humanity house]. When she was well enough to go out again, she went to the police to ask about her complaint. They told her, “we called your husband, he said you fell and that is why you are bruised.” She said the police did not do anything more.[46]

Ramla is a 50-year-old mother of four from Blida. She used to work as a cleaner in a bank. Married in 1991, she got divorced in 2014. She said that her husband started beating her two weeks after they got married. He pulled her by her hair, and beat her on her arms and back with his belt. This often occurred when he came home drunk. She said he forced her to give him all of her salary.[47]

Ramla said she finally decided to divorce him after a particularly severe beating in February 2013. Her husband had asked her to go to the bank to withdraw money for him. When she returned, he insulted her for not withdrawing enough. She said he took an iron rod and beat her on her back, including near her kidneys. She said the neighbors intervened when they heard her cries and walked her to the police station of the third district in Blida. She said she was bleeding and could barely walk. When the policeman there saw her, he asked her who did this to her. She said it was her husband. She said the officer walked out of the commissariat, stopped a passing car, and asked the driver to take her to the hospital. She said the policeman did not do anything more. When she went to complain to the police station the following day, the same policeman took her statement. However, she never heard from the police again. She said the police did not go back to her house to investigate, interrogate her husband, or interview her neighbors. She said she filed a request for divorce in May 2013 based on a unilateral request procedure and got divorced almost a year later.

Mariem, from Blida, is 36 years old. She said she grew up in a poor family and got married at 26 years old, in 2005, to a man she loved. She said the problems started in June 2013 when she was pregnant for the third time. He wanted to throw her out of the house. When she resisted, he punched her in the face and pushed her out. She said she had no money or documents with her. A neighbor accompanied Mariem to the hospital. The forensic doctor gave her a medical certificate prescribing ten days of rest. She then went to the police station to file a complaint. She gave the policemen the certificate, and told them that her husband threw her out of the house. “One of the policeman there told me, ‘This is none of my business. It’s a private family matter. You should go to court,’” she recalled.[48]

She said she went to stay with her brother, who helped her find a lawyer. On May 31, 2015, she asked for a unilateral divorce for “damage,” as permitted in the family code. She obtained it on October 28, 2015 from the first instance court in Blida.

Hasna, is a 31-year-old mother of four from a middle-class family in Oran. She said she married ten years ago and stopped working shortly after getting married. When she became pregnant for the first time, her husband did not want the child. She said that on several occasions he grabbed her by her arms and shoved her. A year following their marriage she gave birth to their first daughter. The violence continued year after year.

In September 2014, he asked her to leave the house and go live with her parents. When she refused, he grabbed her and threw her against the wall, slapped her, and punched her in the face. She said she escaped the house and ran outside in her pajamas. She approached the first policeman she saw on the street, in tears. The policeman told her he could not do anything and that she had to go to the police station. He gave her money for a taxi, and she went to the police station.

At the Miramar police station, the policeman told me “This is a family affair. This is not our business. This is your husband. Maybe he was angry. He will come back to his senses. Go and find some elders who can calm things down. Otherwise, if you file a complaint, he will divorce you.” I thought: if a police officer says this, he must be right, I should go back. And I went back.

She said husband’s mistreatment and the beatings of her continued. In March 2015, they argued in the car parked in the parking lot in front of their house, in front of two of their older children. She said she was wearing sunglasses, he slapped her on the face and the sunglasses injured her in her temples. She was bleeding. When she told him that she will complain to the police, he told her, “Go to the police, in fact I will take you to the police.” They went to the Miramar police station with the children. The policemen told her that if she wants, she can file a complaint, but the children begged her not to. She didn’t. She said after that she went back to live with him for several months. Then he pressed her to accept the divorce, and on September 13, 2015, they got divorced. He provided her the child maintenance and she was able to keep their apartment.

Hanan, who endured years of beating and humiliation from her husband said that one of the most severe episodes occurred during a visit to his parents’ house on October 11, 2009.[49] That day, her husband slapped their eldest daughter on the face and ear during an argument. When Hanan screamed at him to stop, he turned to her and punched her in the face, breaking her nose. She went to the forensic doctor with her daughter. Human Rights Watch reviewed the forensic doctor’s certificate, dated October 11, 2009. It stated that Hanan had suffered a broken nose and psychological shock, and prescribed 16 days of rest. Human Rights Watch also reviewed her daughter’s medical certificate, prepared by the same doctor on the same day, which stated that she had a “tympanic membrane perforation” (ruptured eardrum).[50]

She said she tried with her two daughters to go back to his parents’ house to retrieve their bags and personal documents, such as identity cards and passports, but he did not let them in or give them their belongings. They went to the sixth district police station to file a complaint against him.

The policeman there told me, “This is not our mandate, it’s the prosecutor’s mandate. We cannot interfere between a man and his wife.” I had my nose broken, I had bruises on my face, and this is what he says.

Hanan said she went with her children to stay with her parents. She filed a request for recovery of their personal documents, with the prosecutor’s office at the First Instance Court in Oran. Human Rights Watch reviewed three documents, dated November 3, 8, and 10, 2009, in which the prosecutor ordered the police station of the fifteenth district of Oran to intervene immediately in order to help her recover her documents.[51]

She said for each of these orders she had to go to the prosecutor’s office, then to the police to deliver the requisition orders and then back again to the prosecutor to report about the lack of action from the police. On her follow-up visits, when she asked the police what they had done to recover her documents, they would say that they went to the house but did not find him. She said that they did not attempt to do anything else to help her.

V. Judicial Response to Domestic Violence

There are no comprehensive statistics listing the number of prosecutions brought for violence against women and the number of convictions obtained. Consequently, it remains difficult to assess the extent to which the Algerian authorities comply with their obligations to investigate and punish crimes involving domestic violence. This lack of official data led the CEDAW Committee to recommend in 2012 that Algerian authorities establish a database of information on domestic and sexual violence showing the number of complaints received, investigations undertaken, prosecutions mounted, convictions obtained, and sentences imposed on perpetrators as a basis for the government’s reporting to the Committee.[52]

On May 25, 2016, Human Rights Watch sent a letter to the Algerian government requesting data on domestic violence complaints and criminal cases but received no reply.

The Handbook for Legislation on Violence against Women recommends the creation of specialized prosecutor units on violence against women and to provide adequate funding for their work and specialized training of their staff.[53]

Law no. 15-19 does not envisage the creation of such specialized prosecutorial units, which means that the current Algerian Code of Criminal Procedure will apply to new cases of domestic violence.

Under this code, the public prosecutor’s office instigates criminal proceedings and enforces the law.[54] He is in charge of directing the activities of the judicial police, receiving complaints and denunciations, and deciding whether to initiate a prosecution or to close the case without further action.[55] Under the code, once an investigation is opened by a decision of the prosecutor, the investigative judge takes the lead and is in charge of judicial investigations.[56] The preliminary investigation led by the investigative judge is compulsory if the offense constitutes a crime and therefore punishable by over five years imprisonment. It is optional for minor offenses. It may also be initiated for petty offenses if requested by the prosecutor.[57]

Evidentiary Requirements for Domestic Violence

Human Rights Watch received contrasting information about the judicial system’s handling of evidence in domestic violence cases. Some lawyers said they have seen judges unreasonably insist on certain kinds of evidence, such as eyewitnesses, in domestic violence cases, often an impossibility since most abuse takes place behind closed doors. Lawyers have also said that the medical certificate or the victims’ accounts are considered insufficient for conviction.[58]

The Code of Criminal Procedures allows the judge to establish an offense using “any kind of evidence” that is produced in court and examined by all parties in the trial.[59] Likewise, the 2015 amendment to the penal code, introducing article 266(bis) relating to domestic violence, provides that: “The State of domestic violence can be proved by any means.”[60]

Human Rights Watch spoke with several victims who had differing experiences with the way the judiciary handled their cases. In some instances, the victim said the judge accepted the medical certificate and her own account of the violence as evidence sufficient to convict the husband.

This was the case of Rabiaa, 46, a former nurse. She married in 2008 and moved with her husband to London, where she gave birth to two children. Her husband started beating her shortly after their relocation to London. They returned to Algiers in August 2014. She said that on October 27, 2014, her husband banged her head against a wall in their house in Algiers and beat her, injuring her right eye. Her brother took her to a hospital in Algiers. The forensic doctor gave her a medical certificate specifying the period of physical incapacity for 15 days. The following day she filed a complaint against her husband at the Rouiba police station in Algiers. On March 26, 2014, section for minor offenses at the court of first instance of Rouiba sentenced her husband to two months in prison and a fine of 16,000 Dinars (US$145). She said the sitting judge based his decision on the forensic doctor’s evaluation of her physical incapacitation and on her own accounts of the violence.[61] On appeal, the court suspended the two-month sentence.

Amira, 36, from Oran with two children, told Human Rights Watch that her husband, whom she married in 2004, beat her from the beginning of their marriage. In June 2013, while he was beating their daughter, she tried to stop him. She said he went to the kitchen, took a knife, and came back to the living room and grabbed her hair. When she raised her hand in self-defense, she sustained a slash wound between her thumb and index finger. She went to a nearby hospital, where she received first aid and a forensic doctor gave her period of physical incapacity for 15 days. Amira said that with help from a lawyer, she filed a complaint with the prosecutor’s office at the first instance court of Oran. That court sentenced her husband to one year in prison. On appeal, her husband denied injuring her, saying her wound had resulted from her own negligence with kitchen appliances. Amira said the appeals judge asked her if she could prove the violence through witness testimonies other than her daughter. She could not. The appeals court ended up overturning the prison sentence against her husband.[62]

Human Rights Watch has long documented in several countries around the world how the absence of guidelines on evidentiary rules can affect women’s ability to prove that domestic violence occurred. As such attacks tend to happen in homes behind closed doors, often there are no direct witnesses other than children, in some cases.

Lack of Standards on Forensic Expertise and Evaluation of Incapacitation

The penal code links the severity of the punishment to the severity of the injury suffered by the victim, as determined by the physician who completes the medical certificate.

Before the 2015 amendments to the penal code relating to domestic violence, most cases of domestic violence were prosecuted under the penal code provisions on the crime of assault, which relate the severity of the sentence to the extent of incapacitation occasioned by the physical injuries.

Article 264 provides for a prison term between two months and five years and a fine from 100,000 to 500,000 dinars (approximately $911 to $4,500) to anyone who intentionally inflicts injuries, beats, or commits other acts of violence against others, if the assault results in a physical incapacity of more than 15 days. The penalties increase to 10 years in prison in cases resulting in loss of limbs, bodily function, blindness, or permanent disability. It could reach up to 20 years if the assault results in unintentional death.[63]

If incapacity is judged to be 15 days or fewer, the offense is classified as a minor offense (“contravention”) under article 442 of the penal code and is punished by a prison term from 10 days to 2 months, in addition to a fine of between 8,000 to 16,000 dinars ($72 to $144).

Law no.15-19, the amendment that introduced heavier sentences where the victim of the assault is a current or ex-spouse to the penal code, continues the practice of tying the sentence to the extent of incapacitation caused by physical injuries. If an assault causes injuries that incapacitate the victim for up to and including 15 days, the offender can be sentenced from 1 to 3 years in prison. When incapacitation lasts more than 15 days, the penalty increases to between 2 and 5 years in prison. The penalties further increase to between 10 and 20 years in prison in cases resulting in loss of limb, bodily function, blindness, or permanent disability. It could reach life in prison if the assault results in death.

In her 2011 report, the UN Special Rapporteur on violence against women stated:

A further obstacle to reporting cases of physical violence is found in the requirement of injury as part of the necessary forensic evidence, failing which a complaint will not be pursued by law enforcement authorities. Consequently, the role of forensic doctors, who can grade the injuries based on criteria set forth in the Criminal Code, is of extreme importance in determining the charges that might be brought against the perpetrator. During discussions with the Special Rapporteur, civil society organizations and several victims expressed concern at the very small number of forensic doctors in Algeria, their limited working hours (usually morning shifts only) and their reluctance to issue medical certificates for injuries that automatically lead to criminal proceedings. This reluctance by doctors is allegedly due to the fact that they want to avoid subsequent participation as expert witnesses in court cases.

The focus in the law on incapacitation as a determinative criterion for sentencing is problematic in several respects. It assigns a key, though indirect, role to forensic doctors in determining sentences, by virtue of the medical reports they write indicating the number of days of incapacitation. Yet, Algeria’s law is silent about the criteria and elements to be used by forensic doctors to determine the period of incapacitation. This lack of guidance leaves doctors with wide discretion and potentially arbitrary influence over sentencing in criminal cases. The approach also ignores the reality that domestic violence often results in cumulative smaller physical injuries, which may last fewer than 15 days of incapacitation, or other nonphysical or less-visible harm such as brain trauma.[64] The World Health Organization (WHO) noted that in addition to physical injury and “possibly far more common are ailments that often have no identifiable medical cause or are difficult to diagnose. These are sometimes referred to as “functional disorders” or “stress-related conditions” and include irritable bowel syndrome, gastrointestinal symptoms, fibromyalgia, various chronic pain syndromes, and exacerbation of asthma.”[65]

Human Rights Watch interviewed 20 victims with various forms of injuries, ranging from concussions to permanent injuries. The doctor’s determination of the physical injuries varied greatly. In some cases of what appeared to have been severe injuries, the forensic doctors gave a medical certificate of less than 15 days.

Salwa, from Annaba, suffered years of mistreatment from her husband. She said that, in January 2011, he hung her with wires on a bar in the ceiling of their bedroom and lacerated her breasts with scissors until she fainted. She was able to escape with the help of her sister-in-law and went to the Annaba hospital. After giving her superficial treatment, the healthcare providers told her to go to the police. The police sent her with a requisition order to the forensic doctor, who gave her 14 days of sick leave due to physical incapacitation. Human Rights Watch interviewed two service providers in the shelter that hosted Salwa at that time. They said that when she came to the shelter, she was still bleeding from the mutilations of her breasts. They called a doctor and a nurse who changed her bandages every day for more than a week.[66]

Hassiba said she has a permanent mobility problem as a result of her husband’s beatings. On November 14, 2008, during a violent episode, her husband took a chair and threw it at her, hitting her head. She said she was in terrible pain and, after several minutes, felt that she could not move her left arm and leg. Hassiba went to a neighbor and asked her to call her father. Her father took her to the hospital, where they conducted medical exams. She said the exams showed that some nerves in her brain were damaged and that, as a result, she had been paralyzed in her left arm and leg. Human Rights Watch observed during an interview with her, in April 2016, that she could hardly move her left arm and was still limping. She said that, on the day of the attack, she went to the police of the eighteenth district in Oran with the results of the medical exams in order to file a complaint. They wrote her statement and sent her with a requisition order to the forensic doctor of the Oran hospital. The doctor gave her 13 days of sick leave due to physical incapacitation.[67] Human Rights Watch reviewed the Oran court’s first instance and appeal judgments in this case. On April 8, 2009, the first instance court sentenced Hassiba’s husband to pay fine of 8,000 DZD [US$73] based on the characterization of the act as a minor offense under article 442 of the penal code. In its judgment on October 24, 2009, the appeals court maintained the fine and added a prison sentence of two months.[68]

The court handed down its sentence before the new law took effect. However, even under the new law, the court would rely on the forensic doctors’ assessment of 13 days’ incapacitation in classifying the offense, resulting in one to three years’ imprisonment rather than the 10 to 20 years if the doctor had determined her injuries to be permanent disability.

VI. Algeria’s Legal Framework Compared to International Legal Obligations

Algeria’s International Obligations on Violence Against Women

Failure to protect women and girls from domestic violence, provide adequate services, and ensure access to justice violates not only Algeria’s national constitution, but also its binding international human rights obligations. The Algerian constitution, adopted in 1996, emphasizes equality, including between women and men. Amendments to the constitution that entered in force in March 2016 added that the “state works to attain parity between women and men in the job market” and “encourages the promotion of women in positions of responsibility in public institutions and in businesses.”[69]

Algeria is a party to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) since 1996. The convention calls on states to take a number of measures to eliminate all forms of discrimination on the basis of sex, including by private actors, so as to ensure women’s full enjoyment of their human rights.[70] Algeria has also signed, but not ratified, the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa, otherwise known as the Maputo Protocol, which calls on states to take comprehensive measures and legislations to end violence against women.

The CEDAW Committee, the UN expert body that monitors implementation of CEDAW, in its General Recommendations No. 19 and No. 28 makes clear that gender-based violence is considered a form of discrimination and may be considered a violation of CEDAW, whether committed by state or private actors.[71] The committee explained that: “States may also be responsible for private acts if they fail to act with due diligence to prevent violations of rights or to investigate and punish acts of violence.”[72] The Committee has stated in particular that “[f]amily violence is one of the most insidious forms of violence against women” and that such violence presents risks to women’s health and ability to fully participate in private and public life.[73]

The CEDAW Committee has identified key steps necessary to combat violence against women, among them: effective legal measures, including penal sanctions, civil remedies, and compensatory provisions; preventive measures, including public information and education programs to change attitudes about the roles and status of men and women; and protective measures, including shelters, counseling, rehabilitation, and support services.[74]

Similarly, the UN General Assembly has urged governments to take specific law enforcement measures to combat domestic violence through its Resolution on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice Measures to Eliminate Violence against Women.[75]

Violence prevents women from enjoying a host of other rights stipulated in other treaties ratified by Algeria. These rights include the right not to be subject to cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment, security of person, and in extreme cases, the right to life.[76] Algeria has also ratified other treaties that contain provisions relevant to domestic violence, including the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC)[77], the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR)[78], the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR)[79], and the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment.[80] These include provisions on the rights to life, health, physical integrity, nondiscrimination, an adequate standard of living (including housing), a remedy, and freedom from cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment.

In its last two reports on Algeria from 2005 and 2012, the CEDAW committee recalled the need to guarantee human rights to all women victims of violence and those in vulnerable situations, particularly the right to be represented by a lawyer and to receive medical and psychological care, as well as access to shelter with a view to their social and economic reintegration.”[81]

Gaps in New Law on Domestic Violence Compared to International Standards

The Algerian Parliament passed Law no.15-19, on December 10, 2016, amending the penal code by specifying several forms of domestic violence as distinct offenses and imposing heavier sentences on them than other forms of violence.[82] The law also expanded the scope of sexual harassment and strengthened penalties for it, as well as criminalized harassment in public spaces.[83] While this is a step forward in recognizing domestic violence as a serious offense, it falls short of comprehensive legislation on domestic violence.

In UN Women’s Handbook for Legislation on Violence against Women, it is noted that “to date, many laws on violence against women have focused primarily on criminalization” and legal frameworks should move beyond this limited approach to make effective use of a range of areas of the law. They call for legislation that is “comprehensive and multidisciplinary, criminalizing all forms of violence against women and encompassing issues of prevention, protection, survivor empowerment and support (health, economic, social, psychological), as well as adequate punishment of perpetrators and availability of remedies for survivors.”[84]

Algeria’s neighboring countries such as Morocco and Tunisia are considering draft legislation on violence against women including domestic violence, which while still weaker than international standards, go further than Algeria’s law on criminalizing forms of domestic violence, such as by establishing specialized committees or units to combat violence against women, protection measures, and other services for survivors.

The following analysis and recommendations reflect the gaps and key elements needed for legislation to better prevent domestic violence, protect survivors, and prosecute abusers.

Definition and Scope

Before the new law was introduced, courts prosecuted acts of domestic violence under general assault and violence provisions of the penal code. Although the law criminalizes various forms of domestic violence, it contains no comprehensive definition of the term. UN Women’s Handbook for Legislation on Violence against Women calls for a comprehensive definition that can encompass physical, sexual, psychological, and economic violence.[85] Law no. 15-19 increases the penalties for assault to as much as 20 years in prison when the victim is a current or ex-spouse, depending on the victim’s injuries, or a life sentence where such attacks result in death.[86]

The law criminalizes other forms of domestic violence, including psychological and some economic violence. For instance, if a person repeatedly insults his spouse or ex-spouse or subjects her to psychological violence affecting her dignity or her physical or psychological wellbeing, he can face a prison sentence of between one and three years.[87] A person who coerces or intimidates his spouse by any means in order to use her financial resources can also be sentenced to up to two years in prison.[88] In addition, theft between spouses is also now an offense.[89]

While the law does criminalize forms of psychological and economic violence, it should be amended to ensure that “coercive control” is a key part of these acts. Coercive control includes a range of acts designed to make victims subordinate and/or dependent by isolating them from sources of support, exploiting their resources and capacities for personal gain, depriving them of the means needed for independence, resistance, and escape, and regulating their everyday behavior.”[90]

UN Women have warned that there is a risk that violent abusers will manipulate the purpose of laws on psychological and economic violence “by claiming that they have been psychologically or economically abused by their victims. For example, an angry or disgruntled violent abuser may seek a protection order against his wife because she used his property. Another example is that an abuser may claim that physical violence is an appropriate response to his wife’s insults. Even when abusers do not turn claims of psychological and economic violence against their victims, these types of abuse may be very difficult to prove in legal proceedings.”[91]

As such the article on psychological violence should be amended in line with the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) recommendation that such acts are defined “as controlling, coercive or threatening behavior or intentional conduct seriously impairing a person’s psychological integrity through coercion or threats.”[92] In terms of economic violence, the definition should be amended in line with UN guidance, including the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs guidance on statistical surveys concerning violence against women.[93] The amended language should explain that economic violence includes: an individual’s controlling, coercive, or threatening behavior or intentional conduct aimed at denying an intimate partner access to financial resources, property, and goods; deliberately failing to comply with economic responsibilities, such as alimony or financial support for the family; denying access to employment and education; and denying participation in economic decision-making.

The law provides for penalties of up to three years in prison for assault committed with violence, coercion or threat of violence violating the sexual integrity of the victim. The penalty increases to up to five years in prison if sexual violence is committed by an ascendant (e.g. parents or grandparents).[94] The law does not explicitly criminalize rape by an intimate partner, often referred to as marital rape.

The penal code criminalizes rape with to 10 years’ imprisonment, and where the assault is committed against someone under 16, the penalty doubles to between 10 and 20 years’ imprisonment. However, it does not define rape or sexual assault.

Algeria argued to the CEDAW Committee that its case law shows that it considers rape as an offense involving physical or psychological violence against a woman. The CEDAW Committee nonetheless expressed concern “at the absence in the Criminal Code of a definition of rape including marital rape and other sexual crimes, which should be interpreted as sexual offenses committed in the absence of one’s consent.”[95]

Furthermore, in the amendments to the penal code, the scope of the offenses related to domestic violence does not include all individuals. It considers spouses and ex-spouses as the only potential perpetrators, to the exclusion of other relatives and persons. For example, the provisions on assault, psychological, and economic violence do not apply to individuals in intimate non-marital relationships, individuals with familial ties to one another, or members of the same household. While the assault and psychological violence provisions do relate to spouses and former spouses, regardless of whether they live in the same residence as the victim, the economic violence provision relating to coercing or intimidating in order to use the victim’s financial resources is limited to just spouses and does not provide for whether it applies to couples who do not cohabit.

The UN Handbook for Legislation on Violence against Women recommends that laws on domestic violence apply to “individuals who are or have been in an intimate relationship, including marital, non-marital, same sex and non-cohabiting relationships; individuals with family relationships to one another; and members of the same household.”[96] Many countries have amended their laws in light of these recommendations.[97]

Algerian law criminalizes adultery, which is a sexual relationship between two adults, if one of them or both are married. While consensual sexual relations between an unmarried man and an unmarried woman are not criminalized in Algeria, there are deeply rooted social attitudes that are hostile to sexual relationships outside marriage. This leads to the stigmatization of women living with their partner outside of marriage.

Human Rights Watch documented two cases of unmarried women who lived with abusive partners and who said that their status contributed to preventing them from reporting domestic violence.

Manal, 31, from Algiers, experienced violence since childhood. Her parents divorced when she was four months old, leaving her to be raised by her paternal grandmother and uncles. At the age of 16, she went to live with her father and his wife. She said that during the two years she stayed with them, they subjected her to daily mistreatment including her stepmother shackling her wrists and feet in order to quiet her, both of them locking her inside a room for days, and underfeeding her. She escaped from the house at 18 and briefly ended up in sex work. In 2003, she began a relationship with a man and lived with him in Algiers from 2003 to 2013. She said after a month of living together, he began to beat her. She said he regularly burned her with cigarettes and grabbed her by her hair pulling her around the room. She said once he threw a picture frame at her head. She said she never filed a complaint against him because she didn’t know where to turn for help. She said the fact that she was not married to him was a barrier to reporting violence to the police. She said she was afraid the police would even arrest her if she told them they were not married.[98]

Another woman, Nabila, 33, with a three-year-old daughter, lived with a man in Annaba, for one year, in 2012. They married by fatiha, a traditional form of marriage that is not registered with the authorities. She said he beat her regularly. When she was pregnant, he did not want the baby and he kicked her on her belly to provoke a miscarriage. He locked her inside the apartment for several days and gave her no food.

Nabila said she never went to the police to complain. “I’m not married to him. I have no rights. If I go to the police, they could even put me in prison.”[99]

Nabila gave birth to her daughter in 2013 and was living in a shelter when Human Rights Watch interviewed her in April 2016.

Prevention

Law no. 15-19 makes no mention of measures for prevention of domestic violence.

The UN Committee on Discrimination against Women, which oversees the implementation of the CEDAW, to which Algeria is a state party, states that “[t]raditional attitudes by which women are regarded as subordinate to men or as having stereotyped roles perpetuate widespread practices involving violence or coercion, such as family violence and abuse.”[100]

The CEDAW Committee says: “Effective measures should be taken to overcome these attitudes and practices,” including education and public information programs to help eliminate prejudices which hinder women’s equality. the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa, also known as the Maputo Protocol, which Algeria has signed in 2003 but not yet ratified, also calls on states to “actively promote peace education through curricula and social communication in order to eradicate elements in traditional and cultural beliefs, practices and stereotypes which legitimize and exacerbate the persistence and tolerance of violence against women.”[101]

In its Handbook for Legislation on Violence against Women, UN Women recommends that legislation on violence against women address prevention.[102] This should include measures such as awareness-raising on women’s human rights, educational curricula to modify discriminatory patterns of behavior and gender stereotypes, and sensitizing the media regarding violence against women. UN Women has also issued a Handbook on National Action Plans on Violence against Women, which explains additional prevention measures.[103] The UNODC has published guidance on prevention as well.[104]

Algeria has not set out prevention measures on violence against women in its legislation.

Orders for Protection