Map of Kyrgyzstan

Summary

Gulnara B. and her husband lived together for 15 years before he began brutally attacking her in 2003. One evening in 2012, he returned to their Bishkek home after a school reunion and started to criticize her. She said:

I asked him to calm down, to not insult me. He said, “It’s my home, I can do whatever I want.” I got up and said, “Okay, you can do whatever you want.” I wanted to leave the room but he said, “Stand there.” I looked over and he was already approaching me. I ran away outside. He caught me by the hair. He banged my head against the cement ground. I was very scared. I asked him to forgive me.

Gulnara was hospitalized for 10 days with a severe concussion. During her hospital stay, medical staff reported her case to police without informing her or obtaining her consent. Although Gulnara provided an incident report, the police did not to tell her she could request a protection order against her abuser and never took any action against her husband. During years of beatings, Gulnara attempted to separate from her husband several times, even divorcing him in 2010. But she said she returned to him largely because she felt her children would suffer stigma and shame if they were “fatherless.” After 10 years of abuse, in 2013, Gulnara’s husband stabbed her, and she decided to press charges against him. The case has dragged on for over two years; as of this writing, Gulnara’s husband has faced no conviction or penalties.

Gulnara’s experience demonstrates the multiple ways in which the government of Kyrgyzstan is not providing adequate support, protection, and remedies to survivors of domestic violence.

********

This report updates a 2006 Human Rights Watch report on domestic violence and bride kidnapping in Kyrgyzstan. In the intervening years, Kyrgyzstan’s government has introduced legal amendments and awareness-raising campaigns in attempts to change attitudes towards violence against women and reduce impunity. For example, in 2013 the government increased penalties for bride kidnapping. Unfortunately, problems persist.

The report documents the government’s failure to ensure provision of services and support for survivors, utilize available means of protection, investigate and prosecute cases, and penalize perpetrators in cases of domestic violence. In interviews with survivors of domestic violence, service providers, police, judges, community leaders, and representatives of state agencies, Human Rights Watch found that domestic violence remains a grave concern in Kyrgyzstan, and that multiple barriers hinder survivors from seeking help or accessing justice.

Human Rights Watch documented cases of severe physical and psychological domestic abuse, sometimes with long-lasting consequences. Women told Human Rights Watch about instances in which perpetrators pounded their heads against walls and pavement; broke their jaws; caused concussions and skull fractures; stabbed them; beat them with rolling pins, metal kitchenware, and other objects; locked them outside in extreme cold without shoes or appropriate clothing; beat them while pregnant to the point of miscarriage; chased them with knives and spades; attempted to choke or suffocate them; threatened to kill them; spit in their mouths; and verbally humiliated them at their workplaces.

Several women also told Human Rights Watch that they were forced into marriage, sometimes through abduction; three of the survivors Human Rights Watch interviewed were married between the ages of 15 and 17, below the legal age of 18. In many cases, women told Human Rights Watch that they experienced domestic abuse for years, almost always at the hands of husbands or partners, but also by in-laws and, in one case, a brother. Some of the women suffer from long-term physical or psychological distress as a result of domestic violence.

Survivors of domestic violence in Kyrgyzstan face a daunting array of barriers to seeking assistance, protection, and justice. Social barriers include pressure to maintain the family at all costs, stigma and shame, economic dependence, vulnerability and isolation—especially among those in unregistered marriages—and fear of reprisals by abusers. Other obstacles include lack of services for survivors of domestic violence, particularly shelters, and inaction or hostility on the part of law enforcement and courts. In multiple ways, Kyrgyzstan is violating its own 2003 law on domestic violence, as well as its binding international human rights obligations.

Women and girls in Kyrgyzstan suffer high rates of domestic violence, yet few cases are reported and even fewer are prosecuted. In Kyrgyzstan’s 2012 Demographic and Health Survey, 28 percent of women and girls aged 15-49 who are or have ever been married reported having experienced domestic violence (defined in the survey as physical, sexual, or emotional violence by a spouse or partner). According to the survey, 41 percent of women and girls who experienced physical or sexual violence never sought help or told anyone about the violence.

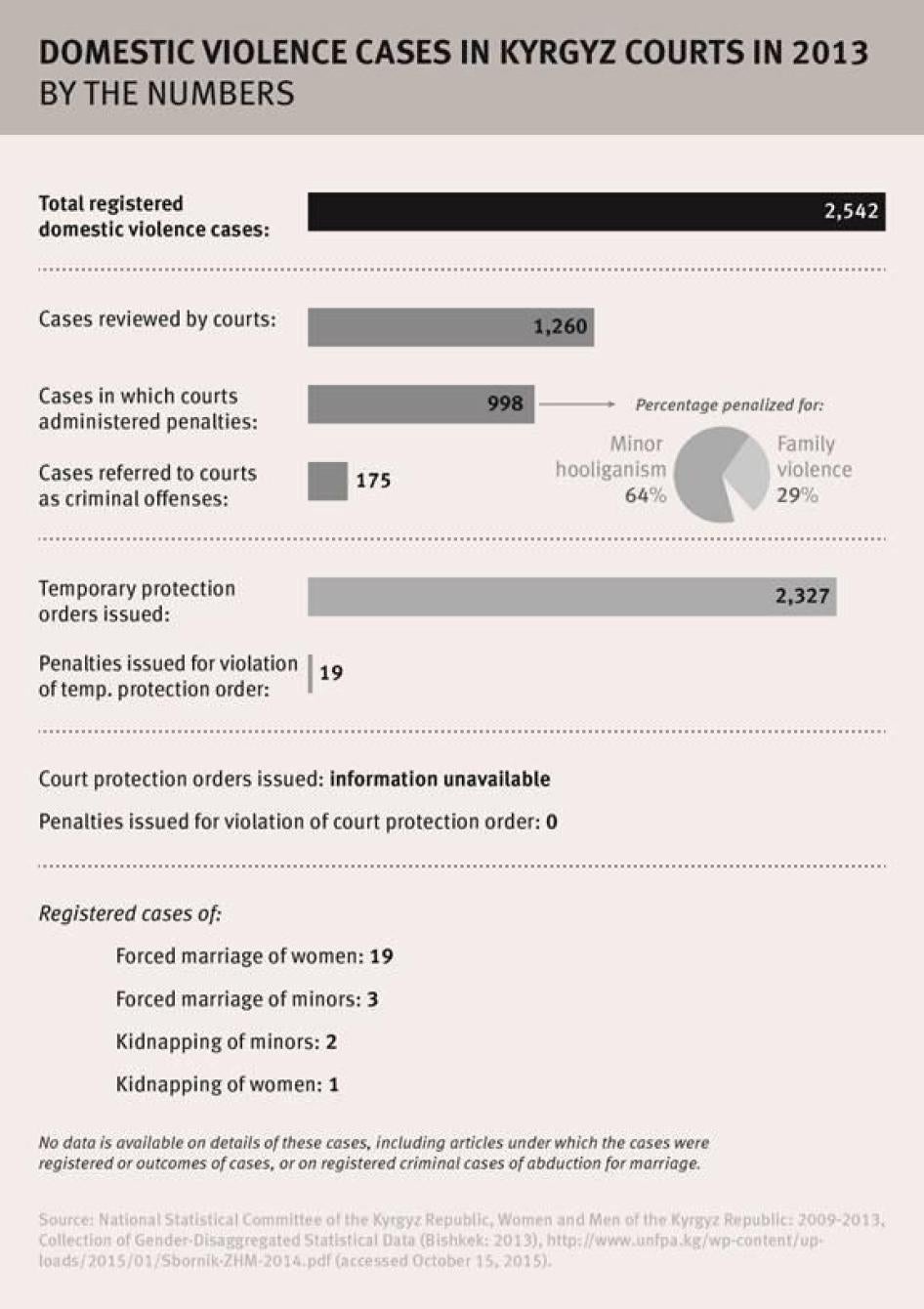

Government data shows that only a fraction of domestic violence complaints registered with police are reviewed by courts. Those that do reach courts are frequently considered administrative offenses, not crimes, and thus face lighter penalties. Even among administrative cases, few perpetrators are convicted of domestic violence; most face penalties for offenses such as “disorderly conduct.”

This is a critical time to examine Kyrgyzstan’s record on domestic violence. A new law developed by experts and government agencies, which would overhaul the 2003 Domestic Violence Law, is due to be finalized for parliamentary review by the end of 2015. It is vital that any new domestic violence legislation retains those elements of the existing law that ensure protections and redress, while at the same time addresses its weaknesses and incorporates enforcement mechanisms. While the 2003 Domestic Violence Law was groundbreaking, it promised far more than it accomplished.

Parliament is also considering amendments to the Criminal Code and Criminal Procedure Code. These have the potential to strengthen the existing legislative framework on domestic violence.

Not all police, judges, and state service providers ignore their responsibilities with respect to domestic violence. Some police told Human Rights Watch that they regularly take domestic violence complaints and issue temporary protection orders. Some survivors said that judges helped them obtain a divorce or access alimony from abusive husbands. Ministry of Health and Ministry of Internal Affairs officials have introduced manuals offering guidance on domestic violence response and data collection. However, service provision for survivors of domestic violence, including shelter, psychosocial care, and facilitation of access to justice, lies almost entirely in the hands of nongovernmental organizations, most of which receive no state support.

Kyrgyzstan has ratified several international human rights treaties that obligate it to protect women and girls from violence and discrimination. However, it has not ratified an important regional treaty, the Council of Europe Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence against Women and Domestic Violence, which came into force in 2014. Although not a Council of Europe member state, Kyrgyzstan can and should ratify this treaty, which provides detailed guidance on measures to address domestic violence.

The government of Kyrgyzstan should enforce its national laws on violence against women, including domestic violence, and change laws and practices that put women and girls at risk of violence. The Ministry of Internal Affairs, Ministry of Justice, Prosecutor General’s office, and Supreme Court should provide improved and repeated training for police, prosecutors, and judges, and monitor their adherence to laws and policies related to domestic violence. This includes issuing and enforcing protection orders and prosecuting abusers. The government should clearly and publicly state that the safety and welfare of survivors of domestic violence take priority over reconciliation and maintaining family unity. In addition, the government should enforce and clarify laws that limit referral of serious cases of domestic violence to community elders (aksakals) courts, which emphasize reconciliation and may limit survivors’ access to the full range of measures for redress. It should also enforce laws prohibiting marriage below the age of 18 and all forms of forced marriage, including bride kidnapping.

Human Rights Watch found that health care providers reported cases of domestic violence to police without survivors’ consent, which conflicts with recommendations of the World Health Organization and may deter women from seeking care. The government of Kyrgyzstan should issue guidelines specifying that it is not mandatory for medical professionals to report cases of domestic violence against adults to police, and that such reporting should only be done with the survivor’s express consent. In addition, the government should expand key services for survivors of domestic violence, such as shelters and legal assistance. The government should also combat harmful attitudes and social norms that foster domestic violence, victim-blaming, and stigmatization of survivors.

In failing to enforce its laws, the government of Kyrgyzstan has left women and girls facing domestic abuse without a safety net. This is a pivotal moment for Kyrgyzstan to update its legal framework and implement effective systems to stop domestic violence and hold perpetrators to account. Until it does so, the government of Kyrgyzstan continues to put the lives of women and girls at risk.

Key Recommendations

Full recommendations to individual ministries and other bodies are listed at the end of this report. Human Rights Watch recommends that the government of Kyrgyzstan:

- Designate a specific government body responsible for coordination of all policies and measures related to domestic violence.

- Amend the Criminal Code to make clear that, in cases of domestic violence, Criminal Code articles may apply to spouses, partners, former spouses, and former partners regardless of whether the perpetrator and victim are cohabiting or have ever cohabited as well as members of the family, extended family, and in-laws.

- Ensure that domestic violence legislation retains the right of survivors of domestic violence to obtain temporary protection orders and longer-term protection by decision of the court, and that both forms of protection include the option of requiring the perpetrator to vacate a shared residence.

- Amend and enforce Ministry of Internal Affairs Order No. 844 of September 28, 2009, on police duties and procedures on responding to domestic violence t0 include broader protocols for police response to domestic violence in accordance with the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) standards.

- Design and implement a mandatory core curriculum on domestic violence response at the police training institute, as well as in police retraining and qualification courses, in accordance with the above protocols and UNODC standards.

- Design and implement a mandatory core curriculum for training of prosecutors on domestic violence response in accordance with national and international laws and UNODC standards. Train judges on national domestic violence legislation and international obligations, and on domestic violence response.

- Ensure availability of adequate shelter, psychosocial, legal, and other services for survivors of domestic violence, including in rural areas.

- Amend the Practical Guidelines on Effective Documentation of Violence, Torture, and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment and Punishment to clarify, in line with World Health Organization clinical and policy guidelines, that medical personnel should not report cases of domestic violence to police or share case information (including with family members) without the express consent of adult survivors.

Methodology

This report documents the government of Kyrgyzstan’s failure to provide survivors of domestic violence with adequate services, protection, and legal remedies. It is based on Human Rights Watch research conducted in November and December 2014 in three cities in Kyrgyzstan: Bishkek and Naryn in the north and Osh in the south. Additional meetings and interviews were conducted in Bishkek in May 2015. These cities were selected based on consultation with local women’s groups and service providers, and were chosen in an effort to interview survivors representing diverse socioeconomic and ethnic backgrounds.

Human Rights Watch interviewed 28 female survivors of domestic violence ranging in age from 20 to 49. All had experienced physical abuse, and almost all had experienced verbal or psychological abuse as well. Twenty-seven of the survivors reported abuse by their husbands or partners, and several also reported abuse by in-laws; one survivor was abused by her brother. Eleven survivors had experienced forced marriage and three had been married before the legal minimum age of 18. Survivors came from Chuy, Issyk-Kul, Jalal Abad, Naryn, and Osh provinces of Kyrgyzstan. Interviewees included ethnic Kyrgyz, Russian, and Uzbek women. They came from rural and urban areas, with education levels ranging from primary school to graduate degrees. Four of the survivors have or have had alcohol or drug dependence, and two have previously been convicted of crimes and served time in prison.

Human Rights Watch identified survivors with the assistance of local service providers, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and women’s rights activists. Interviews were conducted in Russian, Kyrgyz, or Uzbek languages with the assistance of female interpreters. Two interviews were conducted in Russian by a Russian-speaking researcher. Some survivors declined to be interviewed for fear of stigma or reprisals.

Interviews with survivors were conducted at places of their choosing, including shelters, private homes, and crisis centers. Human Rights Watch informed all interviewees of the purpose of the interview and how information collected would be used, and received verbal consent before conducting the interview. Survivors were also informed of their right to stop or pause the interview at any time. No incentives were provided for interviews; some interviewees who met with Human Rights Watch were provided a small reimbursement for travel expenses. Human Rights Watch referred survivors to available services where appropriate and possible, and took care to minimize retraumatization of interviewees.

Human Rights Watch also spoke with 65 representatives of law enforcement and the criminal and civil justice systems, public and private service providers, NGOs, and community leaders. These included ten staff members of crisis centers and shelters as well as eight representatives of the police, four judges, four lawyers, and five members of aksakals (elders) courts. It also included five health care providers, two religious leaders, and eleven representatives of international NGOs and United Nations agencies. Additional information was gathered from published sources, including laws, government data, United Nations documents, academic research, and media.

Human Rights Watch met with representatives of the Prosecutor General’s office, the Ombudsman for Human Rights, and the Ministries of Health and Justice in December 2014 and with representatives of the Ministry of Internal Affairs in May 2015. The Ministry of Social Development declined multiple requests for meetings at these times. Human Rights Watch submitted written information requests to the Ministries of Internal Affairs, Social Development, Health, and Justice in March 2015; no responses had been received at this writing. These information requests are available on the Human Rights Watch website.

All survivors’ names are pseudonyms and some identifying details have been withheld for their security and privacy. Names and identifying details of some other interviewees have been withheld at their request. Pseudonyms are represented by a first name and initial at the first mention, and then simply the first name. Where names and exact titles of interviewees are used, Human Rights Watch received express consent to do so.

I. Background

Domestic Violence and Child and Forced Marriage in Kyrgyzstan

[My husband] says, “I will kill you. I will stab you. Get out of the house.” He uses swear words. When he says get out of the house, I get out. At times I have to get out in winter…. I just stay outside waiting because if I go to the neighbors’ he will come and wreak havoc there. I wait outside until he goes to sleep. I wait for two or three hours. Sometimes if he doesn’t go to sleep I go to my relatives and stay there overnight with them….To avoid being beaten I run away….I feel depressed. Sometimes I just sit home and cry.

—Nurzat N., 37, Naryn province[1]

Nurzat N. was kidnapped for marriage in Bishkek at age 17 by an acquaintance. She told Human Rights Watch that she fought her kidnappers, but was taken to Naryn and forced to stay with the groom and his family. Within a few years of their marriage, her husband began abusing her physically and psychologically. As in the cases of many of the survivors of domestic violence Human Rights Watch interviewed, Nurzat has not sought assistance from the police, nor had she accessed help from psychosocial or shelter services.[2] She said she feared that involving the police would lead to further abuse, and that leaving is impossible as she would not be able to provide for her children. “I have no one to turn to for help,” she said.[3]

Such experiences are all too common in Kyrgyzstan.[4] In interviews with survivors of domestic violence, service providers, representatives of law enforcement and criminal justice, and community leaders, Human Rights Watch documented cases of brutal and long-lasting physical and psychological abuse. Almost all women interviewed were abused by husbands or partners, and some also experienced violence by in-laws or family members. Women told Human Rights Watch about being beaten, kicked, and attacked with instruments including a rolling pin and knives, sometimes causing significant injuries such as concussions, skull fractures, or miscarriages.

In Kyrgyzstan’s 2012 Demographic and Health Survey, 28 percent of married or formerly married women and girls aged 15-49 reported having experienced physical, sexual, or emotional violence by a spouse or partner.[5] Women and girls also reported frequent attempts by husbands or partners to control or restrict their behavior and movement; 71 percent reported jealousy or anger if they talked to other men; and 68 percent reported that their husbands or partners insisted on knowing their whereabouts at all times.[6] Other government data on violence against women is limited, often referring to registered cases rather than estimating broader prevalence.[7]

Available data indicates that women who experience violence often sustain injuries but may not seek help or divulge the abuse to anyone. In the 2012 Demographic and Health Survey, 56 percent of surveyed women who had experienced domestic violence said they had sustained some form of physical injury; 41 percent of women and girls who experienced physical or sexual violence never sought help or told anyone about the violence.[8]

Survivors and service providers told Human Rights Watch that domestic violence is considered almost normal in Kyrgyzstan. Tomaris M., 46, experienced years of physical and verbal abuse by her husband, but said that she did not perceive it as unusual: “In Kyrgyzstan people think everyone lives like that. All husbands beat their wives. It’s not extraordinary,” she said.[9] Jyrgal K., 46, was kidnapped for marriage and later hospitalized three times due to physical abuse by her husband. She told Human Rights Watch, “My friends would say, ‘We all suffer from the same, but we have to endure. We have to be patient.’”[10] According to Kyrgyzstan’s 2012 Demographic and Health Survey, 33 percent of women and girls and 50 percent of men and boys aged 15-49 believe that a man may be justified in hitting or beating his wife.[11]

Marriage practices prohibited under national law—including child, early, and forced marriage—are also often accepted in Kyrgyzstan. Abduction for marriage, or bride kidnapping, has received significant attention and condemnation from media, academics, international bodies, and the government.[12] However, reports indicate that the practice continues; in its 2014 review of Kyrgyzstan, the UN body monitoring compliance with the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) noted its concern about “the continuing widespread practice of bride-kidnapping of underage girls” as well as increasing incidents of early and forced marriages of girls.[13] The government has done little to monitor the scale of bride kidnapping or other forms of early and forced marriage.[14] Government data on registered crimes for 2013 lists only 10 cases of kidnapping and 22 cases of forced marriage against women and children; it does not provide specific data about the number of cases that involved abduction for marriage or child marriage.[15] Data on child and forced marriages is limited in part because such marriages are typically not registered with the state, and authorities only know about cases when complaints are filed.

Government data does not disaggregate incidences of domestic violence against specific populations such as lesbian and bi-sexual women and transgender men (LBT), women and girls with disabilities, ethnic and religious minorities, HIV-positive women, former prisoners, individuals with drug or alcohol dependence, and elderly women.[16] However, widespread prejudice against such groups likely presents additional obstacles to accessing justice and services.[17]In a report submitted for the 2015 review of Kyrgyzstan’s compliance with the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Violence against Women (CEDAW), NGOs commented that stigmatization of and discrimination against female drug users, women with HIV, sex workers, and members of the LBT population increase their vulnerability to violence and decrease the likelihood that they will seek help.[18] A 2013-2014 study of a self-selecting sample of female drug users found that 80 percent reported experiencing domestic violence in the previous 12 months, but only 22 percent reported accessing services.[19]

Discrimination against the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community in Kyrgyzstan is at risk of being institutionalized: legislation criminalizing the dissemination of information that creates or promotes a “positive attitude toward nontraditional sexual orientation” in the media or public assemblies, commonly referred to as the anti-LGBT “propaganda” bill, is currently under consideration in parliament.[20] The bill passed its first reading in parliament in October 2014 and its second reading in June 2015 by an overwhelming majority (79 in favor, 7 opposed at the first reading; 90 in favor, 2 opposed at the second reading).[21] The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, European Parliament, UN in Kyrgyzstan, Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), and the US embassy in Bishkek have urged the Kyrgyz parliament to reject the pending legislation.[22]

In recent years, the government of Kyrgyzstan has taken some measures to address violence against women and girls, particularly bride kidnapping, which are discussed below. However, domestic violence receives less government attention, though it is often cited as one of the primary rights abuses facing the country’s women. In the concluding observations of their 2015 reviews of Kyrgyzstan, the UN expert bodies that monitor compliance with CEDAW (the CEDAW Committee) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (the CESCR) noted concern regarding the prevalence of domestic violence, which “frequently leads to life-threatening physical injuries.”[23] Similarly, the UN Human Rights Committee, which monitors compliance with the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), expressed concern in 2014 at continued violence against women and underreporting, and “that domestic violence is accepted by the society at large.”[24]

Since Kyrgyzstan’s independence in 1991, international agencies and governments have provided significant financial and technical support to Kyrgyzstan to undertake reforms and implement programs that directly or indirectly address the issue of violence against women. These include: the European Union, which has provided assistance for economic and political reforms; the United Kingdom, which supports democratization, security, and development; Germany, which supports poverty reduction and sustainable development; and the United States, which has contributed assistance for development of public services, economic growth, and democracy.[25] In addition, the OSCE has supported promotion of human rights, rule of law, and good governance, and the World Bank has provided assistance for public services, business development, and natural resources management.[26]

In January 2015, the UN Trust Fund to End Violence against Women awarded Kyrgyzstan’s Ministry of Social Development a three-year grant of approximately US$719,000.[27] Four local NGOs will serve as implementing partners. Plans for use of the funds include strengthening the legislative and policy framework on domestic violence, piloting improved support services for survivors and women at risk, and conducting awareness-raising and advocacy activities.[28] Human Rights Watch was unable to confirm plans for implementation with the Ministry of Social Development as the Ministry declined requests for in-person meetings and written information.

II. Legal and Policy Framework

Legal and Policy Framework on Gender Equality

Kyrgyzstan’s national legislative framework provides protections related to gender equality and women’s rights broadly, as well as to domestic violence specifically. The Constitution and the Law of the Kyrgyz Republic on State Guarantees on the Provision of Equal Rights and Equal Opportunities for Men and Women guarantee gender equality and prohibit sex discrimination.[29]

The government took steps in 2012 to address gender inequality and discrimination by developing a National Strategy to Achieve Gender Equality by 2020 and corresponding National Action Plans.[30] The National Strategy recognizes links between gender inequality and violence against women, and notes high levels of domestic violence and early marriage, as well as the enduring practice of bride kidnapping.[31] The National Action Plan on Achieving Gender Equality in the Kyrgyz Republic for 2012-2014 (NAP) emphasized strengthening women’s economic empowerment and access to justice, including in cases of gender discrimination and gender violence.[32] At the time of writing, a NAP for 2015-2017 was awaiting government approval.[33]

Since 2009, responsibility for gender policy and coordination has shifted among three ministries, and now lies with the Department of Gender Policy under the Ministry of Social Development.[34] The National Strategy recognizes that implementation of past gender policy has failed in part due to the weakness of national mechanisms and lack of coordination.[35] In its 2015 concluding observations on Kyrgyzstan, the CEDAW Committee noted concern that frequent relocation of the state body overseeing gender policy has limited its effectiveness.[36] It also said that the current Department of Gender Policy “lacks necessary authority and capacity, including adequate human and financial resources and capacity to ensure that gender equality policies are properly developed and fully implemented.”[37]

Legal Framework on Domestic Violence

Kyrgyzstan’s law on domestic violence was adopted in 2003 following civil society mobilization and pressure: women’s NGOs collected 30,000 citizen signatures and introduced the draft law on the basis of the then-Constitution’s popular legislative initiative.[38]

In many ways, the 2003 Law on Social and Legal Protection against Domestic Violence (hereafter “Domestic Violence Law”) establishes a strong framework for providing support and protection to survivors of domestic violence. The law defines domestic violence (referred to in the law as “family violence”) as “any deliberate action of one member of a family against another, if that action infringes on the legal rights and freedoms of the family member, causes him/her physical or psychological suffering and moral loss or poses a threat for physical or personal development of a minor member of the family.”[39] The law addresses not only physical but also psychological and sexual violence in the family.[40] Moreover, the law does not limit its definition of “family” to relatives or spouses; rather, it includes “spouses, relatives or live-in partners” and specifies that the law applies to partners in unregistered marriages.[41] The law falls short, however, of ensuring protections for non-cohabiting current or former partners, spouses, or relatives, leaving a critical gap in protection for women and girls who have never lived or are no longer living with boyfriends, partners, spouses, or in-laws who abused them.

The Domestic Violence Law details not only a survivor’s right to medical, legal, and shelter services, but also her right to seek remedies. Article 6 guarantees the survivor’s right to file a complaint with police or prosecutors and to submit an application to instigate a criminal investigation.[42] It also offers a survivor the option to bring her case before a community justice mechanism called the court of aksakals, or elders’ court.[43]

While the Domestic Violence Law establishes the importance of multi-sectoral support for survivors of domestic violence, and states that responsibility lies with both government and nongovernmental entities, it remains vague on the government’s role outside of legal and judicial processes.[44] The law places significant responsibility for social service provision to survivors with “specialized social service institutions” without specifying governmental responsibility for supporting or monitoring such institutions.[45] Service providers and women’s rights activists told Human Rights Watch that the government relies largely on NGOs to provide critical services for survivors. They said that almost none of these services receive government funding or material support (with one significant exception being a shelter in Bishkek), and several said that they struggle to keep their doors open.[46] Aleksandra Eliferenko, director of the Association of Crisis Centers in Bishkek, told Human Rights Watch, “The state says it has no funds to provide services. The state is not ready to provide support to crisis centers and victims.”[47] A staff member at another Bishkek-based women’s rights group said that, apart from the one shelter receiving government support, “the others are just trying to survive.”[48]

Service providers and women’s groups told Human Rights Watch that they are concerned that their funding will become even more precarious if parliament passes the “foreign agents” bill, which was initiated in 2013. In June 2015, the bill passed its first reading in parliament by a significant majority (83 in favor, 23 opposed). The bill would require organizations receiving foreign funds and engaging in vaguely defined “political activities” to register as “foreign agents.” This could lead to public perception that they are spies of foreign governments, and also permit the government to suspend operations of those who do not register for up to six months without a court order.[49]

Orders of Protection

A critical element of the Domestic Violence Law is the provision of protection orders, intended to offer survivors immediate and longer-term protection from perpetrators of domestic violence, without requiring them to pursue criminal charges.[50] The law includes two types of orders: temporary protection orders, for immediate, short-term (up to 15 days) protection from an abuser; and court protection orders, for longer-term (up to 6 months) and potentially more stringent protection.[51] In issuing a protection order, police and courts are also obligated to inform the survivor of her right to pursue prosecution of her abuser.[52] Police are responsible for monitoring and enforcing the abuser’s adherence to an order’s conditions.[53]

Administrative and Criminal Codes

Kyrgyzstan’s Code on Administrative Responsibility (“Administrative Code”) contains a specific article on domestic violence. Under Article 66-3, domestic violence constitutes intentional harm that violates a family member’s rights or freedoms and causes minor physical or mental suffering, or developmental damage. The exception is where damage is severe enough to provide grounds for criminal prosecution.[54]

However, government data shows that the majority of domestic violence offenders brought before courts are charged with “disorderly conduct” under article 364 of the Administrative Code, referred to as “minor hooliganism,” rather than with article 66-3 on domestic violence, which carries slightly higher penalties.[55] Article 364 defines “disorderly conduct” as actions that violate public order and disturb the peace.[56] Additional Administrative Code articles that may be applied in cases of domestic violence include those for battery, intentional injury, or death threats.[57]

Unlike the Administrative Code, Kyrgyzstan’s Criminal Code contains no specific article on domestic violence. Rather, individual articles on offenses such as homicide, torture, threat of murder, rape, bigamy and polygamy, and intentional infliction of light or heavy bodily injury or damage to health can be applied in cases of domestic violence.[58] Several of these articles carry harsher penalties when there are aggravating circumstances, including commission of the act against a woman known to be pregnant, or who is financially or otherwise dependent on the perpetrator.[59]

Laws on Bride Kidnapping, Early and Forced Marriage, and Polygamy

Kyrgyzstan’s law forbids forced marriage of any kind, whether or not it includes abduction (so-called bride kidnapping).[60] Following intense public pressure to take action against bride kidnapping, the government increased Criminal Code penalties for bride kidnapping in 2013. Sentences for abduction of someone with intent to marry were increased from a maximum of three years’ imprisonment to five to seven years’ imprisonment for abduction for marriage, and five to ten years when the abductee is under age 17.[61]

Kyrgyzstan’s Family Code establishes 18 as the legal age of marriage, although this may be lowered to 17 with government permission.[62] Both parties must give free consent for marriage.[63] Bigamy and polygamy are also illegal under the Criminal Code.[64] The state only recognizes marriages registered with the Office for Registration of Acts of Civil Status (ZAGS).[65] In 2012, members of parliament introduced a bill to amend the Act on Religious Belief and Practice, which included mandatory state marriage registration prior to conducting a religious marriage. The amendments were rejected in parliament.[66]

III. Obstacles to Protection and Redress

All over my back, my hands, my arms and legs were bruised.… I never went to the doctor or the police. I was afraid of [my husband] very much. If I turn to the police, the next day he might kill me… Sometimes he tried to choke me. I went to the neighbors’ sometimes. They said, “It’s okay, he will become polite later. If you have more children he will be more polite....” I thought, “If he beats me now, he will kill me later.”

—Zarina S., 34, Bishkek[67]

Women who experience domestic violence in Kyrgyzstan face numerous obstacles to accessing help and justice. Intense pressure to “preserve family unity” at all costs, as well as victim-blaming, stigma, economic dependence on abusers, and fear of abusers are among social barriers that trap women in abusive relationships. Marriage practices that violate women’s and girls’ rights and contravene Kyrgyzstan’s laws, including bride kidnapping and other forms of child or forced marriage, often hinder access to help for domestic violence. Women and girls in such marriages frequently experience extreme isolation. Many marriages in Kyrgyzstan are conducted through religious ceremonies and are not registered with the state, resulting in denial of marital property rights.

Women and adolescent girls who seek help may be stymied by a lack of services or inability to access those that exist. Distrust of law enforcement and courts can stop women and girls from reaching out to police or pursuing complaints. In some cases documented by Human Rights Watch, women said they went to police and were turned away. Police resistance to registering survivors’ complaints or issuing temporary protection orders and courts’ failure to issue longer-term protection orders and convict abusers also pose barriers to justice and protection. Human Rights Watch found that, during all phases of reporting domestic violence and seeking help, family, community members, police, and justice officials tend to prioritize reconciliation and encourage women and adolescent girls to keep the family together.

Social Barriers to Accessing Help

Social pressure to keep silent and maintain the family unit, combined with intense fear of stigmatization and reprisals for speaking out, create significant obstacles to reporting domestic violence or accessing services and support. Unregistered, child, or forced marriages create additional impediments.

The “Kyrgyz Mentality” and Preserving the Family

Survivors, service providers, lawyers, judges, police, and other government representatives interviewed by Human Rights Watch spoke overwhelmingly of a “Kyrgyz mentality” that contributes to acceptance of domestic violence and silences victims. Among ethnic Uzbek interviewees, this was expressed as an “Uzbek mentality,” or “our mentality,” referring to the overall population of Kyrgyzstan. Women who experienced domestic abuse or forced or early marriage told Human Rights Watch that they often felt enormous familial and societal pressure to keep abuse secret and endure it for the sake of the family.

Asyl, a 30-year-old from Issyk-Kul province, told Human Rights Watch that she informed her mother-in-law about her husband’s abuse: “My mother-in-law said, ‘Kid, you shouldn’t tell me these things. When he comes home drunk, don’t tell him the next day what he said while he was drunk. You should just be smiley, give him tea. Everything will be okay.’” Asyl said she never told her own relatives about the violence “because my mother-in-law said I shouldn’t tell people what happened in my own [personal] life.”[68]

In general, the “Kyrgyz mentality” favors reconciliation of conflict and maintenance of the family unit, even in cases of domestic violence. This discourages victims from coming forward and, if they do, pressures them to reunite with their abusers. Interviewees said that reconciliation is encouraged, sometimes even by service providers. Baglan U., a member of a community domestic violence committee in a Naryn province village, said, “There are quite a lot of cases of physical [domestic] violence, but they don’t get to court because the Kyrgyz mentality is that they will reconcile anyway. They come to us and we give them moral support to go back home.”[69]

Many women who attempted to leave abusive relationships told Human Rights Watch that their families had encouraged them to return and reconcile, even when they had suffered serious injury. Women who complain about violence in the home or leave abusive partners are perceived as destroying the family, leaving their children as “orphans” subject to immoral upbringing, and bringing disgrace onto themselves and their extended family.

Nurgul V. escaped to her sister’s house after her husband kicked her in the stomach while she was pregnant: “[My parents] said, ‘You have children. You must take care of them. Be patient. Wait until they grow up. Your time will come. You don’t want your kids to be orphans without a father.’”[70]

Bermet K., 25, was hospitalized for 15 days when she was 6 months pregnant following a severe beating by her husband. She said her mother took her home to Bishkek, but soon Bermet’s in-laws came to apologize and bring her back to Naryn. Bermet said, “I told my mom I didn’t want to go back. My mom said, ‘You are pregnant. Maybe he will change his behavior. Go back to the village and give birth.’ I didn’t say anything. I thought maybe she’s right. I agreed and went back.”[71]

Aisuluu G., 27, said that her husband began beating her within several months of kidnapping her for marriage. At first she told herself the abuse was normal: “I thought, my parents also lived like that, so I should put up with it and tolerate it.” In 2011, almost one year later, Aisuluu said she told her mother about the abuse and that she wanted a divorce, but her mother urged her to remain with her husband to avoid bringing shame on her entire family. Aisuluu told Human Rights Watch that this left her even more isolated and vulnerable to abuse: “The fact that my mother returned me back to my husband made things worse. My husband said, ‘You have nowhere to go. Your family won’t support you.’”[72]

In discussing why many domestic violence complaints do not reach the courts, a representative of the Prosecutor General’s office told Human Rights Watch, “For the state, for society it is more important that we have a whole family. Practice shows that children from broken families grow and commit crimes.”[73] Asherbek Khalikov, the head of an aksakals, or community elders, court in Osh, echoed this, saying, “Society with this kind of orphan children cannot be healthy.”[74]

Khalikov told Human Rights Watch about a teacher in his community who suffered long-term physical damage due to severe beatings by her husband. He acknowledged that the woman did not receive compensation for her suffering, but praised the court’s role in reconciling the couple:

A woman can ask for compensation from a man, but in the local women’s mentality that is not the priority. The main thing is to keep the family together. It is more important that the children not be half-orphans, that she [the survivor] not be called a divorcée. It is much more important than compensation from her husband.[75]

The head of one city police unit in Osh said that he opposes reforming Kyrgyzstan’s Domestic Violence Law according to international standards because of the “Kyrgyz mentality”: “If we bring in international standards for punishment for violence at home, then we will destroy many families and this is not appropriate for Kyrgyzstan.”[76]

Such pressure extends to cases of adolescent girls and young women who are abducted for marriage. Human Rights Watch interviewed several women who had been kidnapped for marriage when they were between the ages of 17 and 25. They told Human Rights Watch that family and community members encouraged them to accept their fate and said that “a stone should stay where it is thrown,” meaning that a girl or woman should remain even in a forced or abusive marriage.

Bermet said she was kidnapped in 2007, at age 19, on her way to university classes in Bishkek. She told Human Rights Watch that several men abducted her and held her down as she screamed and kicked in protest during the hours-long drive from Bishkek to Naryn. When Bermet informed her family of the kidnapping, they urged her to stay:

I tried to fight when we got there. They pushed me out [of the car], took me to the house. I called my parents. My mom said, “Now that you are in the house, now don’t shame us. Now stay there. It’s Kyrgyz tradition. You just sit there.”[77]

Bermet said she was afraid and upset, but she stayed and got married.

Asyl N. was abducted for marriage in 2007 at age 23. She told Human Rights Watch that the groom’s family and community compelled her to stay:

On the way [to his village] in the car I tried to get out, but of course I was held down…. When we got to the home I cried. Several old women said, “A stone should stay where it’s thrown.” They said, “She’s at the age when she needs to get married so she needs to stay.”…They persuaded me to stay. I was forced.[78]

Asyl said she was able to contact her own family, and her sisters came to the groom’s home. She said that, “according to Kyrgyz tradition,” they persuaded her to stay and marry.[79]

Interviewees also told Human Rights Watch that Kyrgyz law supports reconciliation. Under the Criminal Code, a perpetrator who commits a minor offense is exempt from criminal liability if he or she reconciles with the victim.[80] This provides additional incentive for abusers or their family members to press for reconciliation. A lawyer who previously provided legal aid to survivors of domestic violence told Human Rights Watch, “Because the law has a provision to close the case if the parties reconcile, halfway through [a survivor’s] relatives persuade her to reconcile and she withdraws the complaint. His [the perpetrator’s] relatives also provide pressure.”[81]

Shame, Stigma, and Victim-blaming

Some survivors said that they did not seek help for domestic violence because they feared stigma and shame. Zarina S., 34, kept silent about her husband’s beatings for six years. She said, “I stayed. It is Kyrgyz tradition. I was afraid of gossip. I thought, what will our neighbors say, what will my relatives say? It will be a shame on our family [if I leave].”[82]

Zahida G., 46, has endured years of physical and verbal abuse from her husband, including a beating that resulted in a 15-day hospital stay for a concussion. In 2012, he attempted to suffocate her with a pillow. She said that she never sought help because she felt embarrassed and ashamed, and feared it would jeopardize her reputation at work: “I was afraid I would be stigmatized….There would be rumors, gossiping.… People would say, ‘Look at her, she gets beaten by her husband, then she comes to work and pretends as if everything is fine in her life.’”[83]

Women who do reveal domestic violence—whether to family, community members, or law enforcement—are seen as ruining the family, leading to a culture of victim-blaming. Tatiana R., 45, a survivor of physical and verbal abuse by her husband, told Human Rights Watch, “The mentality is that if your husband is like that [abusive], you should be blamed. Our society thinks if a woman is not managing to control her husband, it is her fault.”[84]

Batma D., 33, was abused by her in-laws and husband. She said that when she told her husband’s relatives, they replied that it was her responsibility to maintain family harmony, saying, “Next time, in the future, don’t push him to the level of conflict. Don’t argue with him. Just be quiet.”[85]

Victim-blaming is sometimes blatant, even among officials. A judge in Naryn province told Human Rights Watch that, in his view, women sometimes bring violence upon themselves:

The fact is that a husband beat his wife, but maybe he was provoked by his wife. Sometimes there are wives whose behavior provokes violence. Her husband may be unemployed. He comes home every day and very often the wife starts nagging him—you’re not working, you’re not making money, you’re not providing for your family, your children. Sooner or later he gets fed up and beats his wife.[86]

Zarina said that during her divorce proceedings the judge held her responsible for failing to escape her husband’s abuse: “The judge asked me and I told her about everything—the physical violence, everything. She said, ‘Why haven’t you turned to the police at those moments? This is your fault. This is your fault you were suffering and continued to live with him.’”[87]

Aisuluu said that the judge who presided over her first divorce hearing held her responsible for her husband’s abusive behavior: “The judge asked, ‘Why would he beat you? You were not doing the housework? Or are you sleeping around?’” she said.[88]

Lilia K., a 40-year-old from Osh, suffered severe physical abuse by her husband, and has permanent damage to her skull from a beating with a rolling pin. Lilia said she has struggled with alcohol abuse, and that a neighborhood police officer told her this contributes to her husband’s abuse: “The police officer tells me to keep it together, that drinking doesn’t lead to good things, that women with my character are also to blame.”[89]

Economic and Social Dependence and Isolation

After marrying, women and girls in Kyrgyzstan frequently move to their husband’s hometown, often sharing a home with his parents and relatives. As such, new brides are frequently cut off from their own families and social networks. While many women in Kyrgyzstan are highly-skilled professionals, numerous women work outside the home only sporadically or not at all, particularly in rural areas. This can compound women’s isolation and dependence on their partners, spouses, or in-laws.

Survivors repeatedly told Human Rights Watch that they remained in violent relationships in part because of their reliance on their abusers or abusers’ families for shelter and food. Aigul G., a 42-year-old woman from Naryn province, said she had considered filing a complaint with the police but had not done so during nine years of abuse by her husband because she had nowhere to go:

I knew if I went to the police I would have to leave the house and couldn’t go back and I thought, “Where will I go with two kids?” My husband and his [adult] sons would kick me out of the house…. I put up with his beatings, but at least I have a place to stay.[90]

Zahida suffered a skull fracture, concussion, broken nose, and loss of four teeth after one beating by her husband. At the hospital, medical staff learned her injuries were due to domestic violence. “They asked me to write a complaint but I refused because if he was arrested, they [his family] would kick me out of the house and me and my two children would be alone. We would be homeless,” Zahida said.[91]

Feruza S., 27, filed for divorce from her husband after years of severe beatings, one of which caused her to miscarry. She said that sometimes her former husband contacts her and asks her to reconcile, and she considers returning to him. “It’s hard for me to bring up the children on my own. I’m concerned about how I’m going to bring them up if I don’t have a job. I think maybe if I go back to him he will provide food and the children won’t go hungry,” Feruza said.[92]

Isolation can reinforce dependence on abusers. Some women reported that their partners, spouses, or in-laws controlled their movement and refused to let them work outside the home or contact their own families. Zarina told Human Rights Watch that her husband prevented her from leaving the house, even to attend her older brother’s wedding. “When I wanted to go to [visit] my parents he would stop me. He would say, ‘A woman after she is married shouldn’t go to her parents’ house so often. I am your family. You should do everything I say,’” Zarina said.[93]

In some cases, women said that their abusers or in-laws prohibited them from accessing help. Aigul said that when she tried to run away from his abuse, her husband would catch her at the front door and beat her.[94] At one point, Aigul suffered a head injury from her husband’s beatings, but he would not permit her to get medical treatment:

I wanted to go to the hospital, but he wouldn’t let me out of the house. He would say, “No, you will not go to the hospital. If you go to the hospital someone might persuade you to file a complaint against me. You want to send me to prison, you want to get rid of me, but I will be the first to get rid of you.” The next day after I was beaten he wouldn’t let me out of the house.[95]

Aisuluu also told Human Rights Watch that her husband sometimes denied her access to medical care:

He wouldn’t allow me to go to the hospital. I would be unconscious [from his beatings] and he would spray water on my face to wake me up again. He would beat me again, and then spray water on me again. He would continue on like that.[96]

Feruza suffered a miscarriage after a severe beating by her husband. “He beat me throughout the night. In the morning I saw the blood on the sheets. That’s how I knew I had been pregnant,” she said. Her mother-in-law took her to a gynecologist friend for treatment. When she suffered a second miscarriage after her sister-in-law pushed her down the stairs, she said her in-laws again restricted her medical care to their family friend, reducing the likelihood that the abuse would be exposed.[97]

Some women who managed to flee abusive homes said they had no option but to leave their children behind as they sought housing and work. Several said they now struggle to make ends meet and rely on low-paying jobs, sometimes working shifts of more than 24 hours at a time, due to lack of education and work experience.

Most survivors Human Rights Watch interviewed had attempted to leave abusive relationships but ultimately returned, often due to concern about providing for their children. Nurzat suffers psychological and sometimes physical violence from her husband. He threatens to kill her and has kicked her out of the house for hours at a time in the middle of the night, even in winter. She told Human Rights Watch she does not feel able to separate from him. “I would go away for two or three days and come back because I am worried about my children. They are left behind. I was thinking of leaving with the children but I am afraid I won’t be able to provide for my children because I don’t have a place of my own,” she said.[98]

Unregistered, Child, and Forced Marriages

Unregistered, child, and forced marriages heighten women’s and girls’ vulnerability to domestic violence and hinder escape. Such marriages often exacerbate women’s economic dependence and isolation. Forced and child marriages may not be registered initially because they are illegal, and some remain unregistered to avoid detection. Even some legal marriages performed through religious ceremonies remain unregistered with civil authorities, depriving spouses of protections under the Family Code.

Although Kyrgyzstan’s Family Code guarantees rights to marital property for spouses, numerous loopholes may prevent women from realizing this benefit.[99] Couples often marry only in religious ceremonies in Kyrgyzstan. Without additional civil registration, these marriages are not recognized by the state. Under national law, women in unregistered marriages are not entitled to marital property or other rights afforded a spouse, such as alimony and child support.[100] According to staff at an Osh crisis center, some women do not realize that religious marriages are not officially recognized and leave them without the protections granted to spouses under the Family Code.[101]

The nature of some child and forced marriages, including cases of bride kidnapping, can lead to isolation and make seeking help for domestic violence all the more difficult. Bermet said that after she was kidnapped for marriage, her in-laws watched her all the time, even accompanying her to the toilet. Her husband beat her, but she could not confide in her own family. “My in-laws wouldn’t give me the phone to call my parents, so I would speak to them only when they called [me], and my mother-in-law would sit next to me with the phone on loudspeaker,” Bermet said.[102]

While representatives of women’s rights groups and government agencies said they felt that harsher penalties introduced in 2013 had reduced bride kidnapping, none could point to a case that had been prosecuted since the change.[103] Recent data shows significant numbers of bride kidnappings and other forced marriages. In one study based on a 2011-12 nationally-representative survey, 38 percent of married ethnic Kyrgyz women and 31 percent of men reported having been married through bride kidnapping. Within the ethnic Kyrgyz community—the only community for which data was available—rates of bride kidnapping for women, while decreasing, remained at 33 percent for those married between 2002 and 2011.[104]

It is unclear how the government is working to determine the prevalence of bride kidnapping and other forced marriage, given that most cases go unreported.[105] In its November 2013 report to the CESCR, the government confirmed that no official statistics existed on the number of abductions for marriage or percentage of marriages resulting from this practice.[106] A lawyer in Naryn province said, “Bride kidnapping very rarely gets reported to the police. In many cases the women just stay, or, if they don’t stay, they just leave, but they don’t report to the police.”[107] None of the women interviewed by Human Rights Watch who had been forced into marriage or married before the age of 18 had reported it to authorities.

While the minimum legal age of marriage is 18, interviewees said that Muslim religious leaders (mullahs) perform marriages of minors in a religious ceremony called reading nikeh.[108] The head of an aksakals court in Osh told Human Rights Watch, “According to the law, people can’t register marriage before age 18, but mullahs read nikeh to a couple anyway….[E]veryone knows mullahs marry [people] at an early age.”[109] A women’s rights activist in Osh said that religious leaders “provide self-issued certificates” of marriage, but these marriages are seldom officially registered.[110]

Human Rights Watch spoke with an imam who confirmed that he performs marriages without asking for the ages of the bride and groom or proof of civil marriage registration: “According to the religion [Islam], it is not a must to have a [state] registration card [before I marry them]. I don’t ask their ages because their parents come here and ask us to do nikeh.”[111] He said that he will not marry the couple if the girl appears “very young,” which he said could be age 16 or 17 based on his visual assessment.[112]

According to the 2012 Demographic and Health Survey, nearly 14 percent of women currently aged 25 to 49 reported having married by age 18; less than one percent reported having married by age 15.[113] Information in the survey on age of first marriage for girls and women who are currently 15 to 19 years old is incomplete.[114] Government data for 2013 reported that 11,083 girls and women were married between the ages of 15 and 19; no information is provided on how many of these married before age 18.[115] A UN Population Fund (UNFPA) report the same year stated that, nationally, 12.2 percent of girls marry before age 18; in rural areas, this increased to 14.2 percent.[116]

Lax procedures in some religious ceremonies can also result in marriages without women’s full and free consent. The imam Human Rights Watch interviewed said he does not confirm each party’s individual consent to marry. Specifically, he said he does not ask the bride and groom for their consent in private, away from each other or family members: “Because they agree to marriage, they are here. I am reading nikeh in the middle of the ceremony…. So everyone agrees. It is not that people just come and read nikeh. One month before the family comes and asks if we can come [perform the wedding].”[117]

Of ten women who told Human Rights Watch they were subject to forced marriage, eight said that they were married in religious ceremonies and their marriages were never registered with the state.[118] Bermet said a mullah was called to perform the marriage when she was abducted for marriage at age 19. She said the mullah asked for consent only after the ceremony started, while she and the groom were surrounded by family members. Bermet said she tried to signal that she did not agree to the marriage: “The mullah asked [for consent]; you’re normally supposed to say ‘I agree’ three times, but I only said it one time because I didn’t really want to get married.”[119]

In March 2015, the CEDAW Committee noted its concern about ongoing child marriage in Kyrgyzstan despite the legal minimum age of marriage being set at 18. The CEDAW Committee and the CESCR also noted the vulnerability of women in unregistered religious marriages and the denial of economic rights to such women.[120] Both Committees recommended rapid legislative amendments to ensure registration of all marriages and guarantee women’s rights upon termination of any marriage.[121]

Fear of the Abuser

Many survivors told Human Rights Watch that fear of their abuser prevented them from seeking help. Some said their husbands or partners directly warned them that there would be consequences for reporting abuse. Anna D., 43, said of her husband, “He said [to me] many times, ‘If you ever report it to the police or anywhere, I will kill you.’”[122]

After being kidnapped for marriage, Jyrgal lived in a remote village of Naryn province. Her husband hit her on the forehead with a metal mug, leading to a month-long hospitalization. Jyrgal told Human Rights Watch that she was too afraid to tell doctors the cause of her injuries. “My husband said, ‘If you tell the truth, when you come out of the hospital I will kill you,’” Jyrgal said.[123] She said she never went to the police during years of abuse because she feared for her own life and the lives of her children.[124]

Jamila K., 44, said her husband retaliated against her if she discussed his physical abuse outside the home. “If I told anything to anyone he would somehow hear it and would come home and beat me and say, ‘Why did you talk to anyone?’” she said. Once, Jamila confided in a village teacher that her husband was abusing her and her daughter, who was in elementary school. The teacher’s husband told Jamila’s husband to stop. Jamila’s husband reacted by beating her; she said she never told anyone about the abuse again.[125]

Lack of Services and Support for Survivors

Although the Domestic Violence Law establishes survivors’ rights to shelter, medical, and legal services, Human Rights Watch found that services are insufficient and sometimes inaccessible, and a lack of coordination and referral systems hinders women from reaching comprehensive support. When survivors seek medical assistance, cases are sometimes referred to police without the survivor’s consent, violating core principles of working with survivors of gender-based violence and potentially increasing risks to their security.[126]

According to published government data, 7,373 women survivors of domestic violence sought help from crisis centers and psychosocial services in 2013.[127] Under the Domestic Violence Law, survivors have the right to medical treatment and transport to such treatment, accommodation in a safe space, and legal assistance and consultation.[128] The Domestic Violence Law tasks local government authorities and nongovernmental social service organizations with providing “social support” and “relevant consultations” to survivors.[129] This implies that the responsibility of NGOs is on par with that of the government. Article 11 of the Domestic Violence Law refers to responsibilities of state bodies, including public health and social protection authorities, but does not clearly establish their role.[130]

Insufficient Shelter Space

The Domestic Violence Law guarantees survivors the right to accommodation in a shelter for up to 10 days, with possible extensions. Any expenses for shelter stays beyond 10 days are to be covered by the perpetrator.[131]

Government data shows that 483 women and 256 men were provided with shelter by crisis centers and other social service facilities in 2013, but it does not specify how many sought shelter as a result of domestic violence.[132] Human Rights Watch interviewed staff members at nine crisis centers and shelters serving survivors of domestic violence in three provinces of Kyrgyzstan.[133] Staff at only two of the nine facilities reported receiving any government support.[134] The Ministry of Social Development has indicated that, to improve social protection from domestic violence, it is taking steps to establish state crisis centers and train staff from the Office of Social Development on basic psychosocial support for survivors.[135] Human Rights Watch requested confirmation from the Ministry of Social Development about any existing or planned initiatives to address domestic violence, but has not received any response at this writing.

Only four of the organizations that Human Rights Watch visited currently provide any form of shelter services. Two target especially vulnerable women, including former prisoners, alcohol and drug users, and HIV-positive women. While these organizations’ directors said that the majority of their clients have also experienced domestic violence, the services they offer are not intended to support the broader population of domestic abuse survivors. However, the director of one of the organizations explained that they began taking in survivors of domestic violence because there were no other shelters available to them in the area.[136]

Together, the centers Human Rights Watch visited offer a total of approximately three dozen shelter spaces.[137] One organization in Naryn and one in Osh reported that, due to lack of funding, they suspended shelter services in 2011 and 2014 respectively.[138] The director of the center in Osh told Human Rights Watch that, even before it suspended services, the center did not have funding to provide meals and therefore could not accept women with children.[139]

Interviews with survivors and service providers indicate that the number of shelter spaces for domestic violence victims in Kyrgyzstan is far below the need, and significantly less than the ratio recommended by the Council of Europe. The Council of Europe recommends a minimum of one shelter space per 10,000 people where shelters are the predominant or only form of service provision.[140] In Bishkek, for example, the sole shelter that reported receiving government funding offers 15 places for a city population of approximately 950,000.[141] Shelter staff said that it is frequently overcrowded; at times women and children sleep in the corridors, or shelter staff find them temporary housing elsewhere.[142] The former director of a crisis center in Osh said she used to bring clients or their children home with her for lack of other options.[143]

Survivors of domestic violence repeatedly told Human Rights Watch that they remained in abusive situations because they had nowhere else to go. Numerous women said that even their own families would not take them in, especially if they had children. Aigul said that she went to her father’s house in an effort to separate from her abusive husband, but her stepmother objected. “My father took the side of his wife and said, ‘Why are you here?’ So I had to go back [to my husband],” Aigul said.[144] Her father and stepmother were already caring for her two children from her first marriage, and her father made it clear they would not offer further support:

I used to tell my father on many occasions that [my husband is] beating me. He would tell me, “You should put up with it, endure it. Don’t fight back. He’s not going to kill you or stab you. If you fight it you will have to leave your husband. I already brought you up. I take care of your two children—you want me to take care of the others, too?”[145]

Zahida said she felt similarly trapped during years of physical and psychological violence. “I wanted to leave, but because I had no place to go, I stayed. I tried to leave several times. I took the children and went to my sister’s. Then I had to go back home after three or four days because my sister wasn’t that supportive. She would behave in a way showing me that we are not really welcome there,” Zahida said. Though Zahida worked as a medical professional, she said her salary could not cover the cost of housing and supporting her children.[146]

One woman said that she tried to find shelter in Osh for herself and her children, but was turned away and unable to secure a space. Umida N.’s brother broke down the door to her house, beat her face against the floor, kicked her, and threatened her during a dispute over the inheritance of their mother’s home in 2010. She told Human Rights Watch that she approached two or three shelters in the area, but was not given a place. Staff of at least one shelter told her they only accepted victims of human trafficking and that, as a domestic violence survivor, Umida did not meet their criteria, she said. Umida told Human Rights Watch that, at least at that time, shelters were particularly difficult to access for women with accompanying children.[147]

Women who did access shelters and crisis centers told Human Rights Watch that the support was invaluable. Zarina said that a neighbor gave her the phone number for the Sezim shelter in Bishkek in 2009. She said she hid it inside a textbook for five years before finding the courage to contact the shelter. During a series of phone calls, the shelter’s director gave her emotional support and guidance. When Zarina escaped to her uncle’s house and called the shelter, she said the director welcomed her, saying, “Come, we have a space for you.” Zarina stayed in the shelter for three weeks and, at the time of the interview with Human Rights Watch, was living in a Sezim transitional house with her children.[148]

Tomaris withstood years of physical abuse and humiliation by her husband before she also went to Sezim’s shelter with her children in 2013. “Here we felt happy for the first time in many months. We slept for almost 24 hours. We were told that for 21 days we were under their protection—we didn’t have to think about [my husband] coming home drunk. I don’t know why I hadn’t done this before. Thank god I have this shelter,” said Tomaris.[149]

Asya P., a 47-year-old from Jalal Abad province, said that she found temporary refuge from her husband’s abuse at the Podruga center in Osh in 2014:

He would beat me badly. He would chase me out of the apartment without shoes, take the keys and not give them back. Thank god I know this crisis center or I don’t know where I would go in the middle of the night without shoes.[150]

All of the shelters that Human Rights Watch visited were in major urban centers or provincial capitals. Survivors and service providers said that there are few, if any, shelters in rural areas. Women living in rural parts of Naryn province told Human Rights Watch that there were no such facilities near their homes, and they would have to travel at least as far as Naryn city to reach one; some women said the distance and cost would be prohibitive.

Lack of Legal Services for Survivors

Although the Domestic Violence Law includes survivors’ right to legal consultation and assistance, service providers and survivors told Human Rights Watch that there is little such assistance available.[151] A Naryn lawyer who previously offered legal aid said that he stopped due to lack of project funds and he does not know of any free legal services now available to survivors of domestic violence in Naryn. He also noted that many women cannot afford a lawyer; hiring a lawyer to assist in filing a simple complaint, he said, might cost around 500 Kyrgyz soms (approximately US$8).[152]

According to Kyrgyzstan’s Demographic and Health Survey for 2012, of women who had experienced physical or sexual violence, only 1.3 percent sought assistance from a lawyer.[153] Survivors told Human Rights Watch that they did not receive information about legal services unless they visited crisis centers that offered or referred them to such services.

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) guidelines on criminal justice response to violence against women recommend provision of free legal aid to survivors of violence.[154] In a 2012 resolution on elimination of violence against women, the UN General Assembly urged member states to ensure that female survivors of violence are provided necessary legal representation as part of ensuring their full access to both civil and criminal justice systems.[155]

Health Services and Reporting to Police without Survivor Consent

Human Rights Watch interviewed four doctors and one nurse at facilities in three provinces who said that, in their experience, survivors typically exhibit bruises or head injuries (concussions) and sometimes broken bones or spinal injuries.[156] Survivors who spoke with Human Rights Watch confirmed that they suffered concussions, bruises, and broken bones as a result of domestic violence. Sixteen of the twenty-eight survivors sought some form of medical assistance due to domestic abuse; nine of these were hospitalized. According to the 2012 Demographic and Health Survey, 56 percent of women who said they had experienced physical or sexual violence by a spouse reported sustaining some form of injury.[157] Of women who reported seeking help due to domestic violence, only 1.8 percent said they contacted a medical professional.[158] Other government data shows that 600 women received medical treatment as a result of domestic violence in 2013; 822 contacted emergency facilities, indicating potentially serious injuries.[159] In 2012, ambulances responded to 498 cases of domestic violence where the victim was female.[160]

The government introduced a new data collection system on domestic violence for health care workers in 2012. Using standardized forms, all health facilities are instructed to report the number of people seeking medical assistance due to physical, psychological, and sexual domestic violence, disaggregated by age and sex.[161] The Ministry of Health also developed a protocol on medical care for survivors of sexual violence, but it does not contain specific guidelines on caring for survivors of domestic sexual violence.[162]

In December 2014, the government instituted the Practical Guidelines on Effective Medical Documentation of Violence, Torture, and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment and Punishment (Practical Guidelines), which are applicable in cases of domestic violence.[163] Training on the Practical Guidelines was held for 25 professors at the Kyrgyz State Medical Institute for Retraining and Skills Development and for some forensic experts in April and May 2015.[164] The Ministry of Health, along with national and international partners, plans to train personnel at primary health care facilities, forensic medical examiners, and psychiatric and psychological forensic specialists on the Practical Guidelines in 2015.[165]

Most women who visited health facilities after sustaining injuries from domestic violence did not complain to Human Rights Watch about the quality of care they received. However, some women said that they told medical personnel about domestic abuse, but the medical staff did not acknowledge it. Most women said medical staff did not offer referrals to shelter, psychosocial, or legal services. Mahabat T., a 35-year-old from Osh, said that she went to the hospital when she experienced difficulty breathing and hearing after her husband beat her and pushed her against a wall in October 2014. She said medical staff did not acknowledge her abuse: “I said I was beaten by my husband. They said I was bruised. They gave me ointment. They did x-rays and [then] said everything was okay.”[166]

Only one of the four doctors Human Rights Watch interviewed said he had received any training related to treatment of survivors of domestic violence. He said he has participated in training on “European standards” for response to cases of domestic violence, as well as on the new Ministry of Health data collection system.[167] He was unable to recall specific elements of the topics covered, indicating that the training may have been ineffective or inadequate. Another doctor, in Naryn city, said that hospital staff had never participated in any official training regarding response to domestic violence.[168] A Ministry of Health representative told Human Rights Watch that, to her knowledge, state health care professionals do not receive any tailored training on response to domestic violence.[169]

A primary concern with regard to the health system response to domestic violence is the practice of reporting cases to law enforcement without the survivor’s informed consent. The Domestic Violence Law clearly specifies that social service institutions may inform police and the prosecutor’s office of incidents or threats of domestic violence “upon the victim’s consent.”[170] In addition, the law states that personal information, including related to a victim’s health, is protected by law and will be used only with consent of the victim, or where a criminal case is initiated or administrative action taken.[171]

Despite these legal protections, several survivors who sustained injuries told Human Rights Watch that medical staff contacted police without informing or asking them. Gulnara said she was hospitalized with a concussion in 2012. “[At the hospital] they didn’t ask if I wanted them to call the police, the police just came by themselves. They didn’t tell me they were going to call the police,” she said.[172]

After her husband hit her against the wall, kicked her, and locked her in the bedroom, Zahida was taken to an intensive care unit and hospitalized for two weeks. When medical staff heard how she was injured and asked her to file a complaint, she refused for fear of being kicked out of her home. “I told the hospital I was not going to report to the police but still the police arrived. When I told the police I was not going to file a complaint, they went to my home and took my husband to the police station. They took him in the evening and kept him until morning,” Zahida said. After that, she said, her husband only became more careful about how he beat her: “He avoided breaking my nose, my skull, my face. He would suffocate me and give me bruises.”[173]