Summary

Roraima is the deadliest state for women and girls in Brazil. Killings of women rose 139 percent from 2010 to 2015, reaching 11.4 homicides per 100,000 women that year, the latest for which there is data available. The national average is 4.4 killings per 100,000 women—already one of the highest in the world.

Roraima does not collect data to determine how many of the killings of women there are related to domestic violence. However, studies in Brazil and worldwide estimate a large percentage of women are killed by partners or former partners.

Women and girls in Roraima often suffer violent attacks and abuse for years before they summon the courage to report it to the police. When they do, the government’s response is grossly inadequate.

Despite a comprehensive legal framework aimed at improving responses to domestic violence and the genuine commitment of several conscientious police and justice officials Human Rights Watch spoke with in Roraima, we found failures at all points in the trajectory of how domestic violence cases are handled from the moment of abuse forward.

Only a quarter of women who suffer violence in Brazil report it, according to a February 2017 survey that does not provide state-by-state data. In our research, we found that when women in Roraima do call police they face considerable barriers to having their cases heard. In some instances, police do not even respond to calls: military police—the state police force that patrols the streets—told Human Rights Watch that, for lack of personnel, they do not respond to all emergency calls from women who say they are experiencing domestic violence.

Other women are turned away at police stations. Both domestic violence victims and authorities told us that some officers of the civil police—the state police force that receives criminal complaints and investigates crimes—in Boa Vista, the state’s capital, refuse to attend to women who want to file a complaint about an act of domestic violence or seek a protection order. Instead, they direct them to the single “women’s police station” in the state—tasked with registering and investigating crimes against women—even at times when that station is closed.

Even when police receive their complaints, women have to tell their story of abuse, including sexual abuse, in open reception areas, as there are no private rooms to take statements in any police station in the state, including the women’s police station, the chief of civil police told Human Rights Watch.

Not a single civil police officer in Roraima receives training in how to handle domestic violence cases, the chief of police also said. And it shows. Some police officers, when receiving women seeking protection orders, take statements so carelessly that judges lack the basic information they need to decide whether to issue the order.

Civil police are unable to keep up with the volume of complaints they do receive. In Boa Vista, the police have done no investigative work on a backlog of 8,400 domestic violence complaints, according to the head of the women’s police station. Police have formally opened investigations into an additional 5,000 cases in Boa Vista, many of which have been dragging on for years without results, staff at the domestic violence court told Human Rights Watch.

As a result of these failings, more than half of all domestic violence investigations are eventually closed, civil police estimated, because the statute of limitations expires before anyone is charged: most alleged domestic violence crimes languish without the police conducting meaningful investigations or prosecutors ever charging perpetrators. The state is not meeting its obligations to women and girls who are victims of domestic violence, creating an atmosphere of impunity, and missing an opportunity to break the escalation of violence that is common in abusive relationships—and that can lead to women’s deaths.

* * *

The serious problems in Roraima reflect nationwide failures to provide victims of domestic violence with access to justice and protection. Brazil has made significant advances over the years by establishing a legal framework to curb domestic violence, but it is failing to put that into practice.

These failures undermine the human rights of women—rights that are set down in treaties Brazil has ratified. The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) and other human rights treaties require Brazil to show due diligence in preventing violation of rights by private actors and to investigate and punish acts of violence. A state’s consistent failure to do so when women are impacted in far greater proportions by the type of violence amounts to unequal and discriminatory treatment, and constitutes a violation of its obligation to guarantee women equal protection of the law. Brazil has also committed to act effectively to eliminate violence against women, as set out in the Inter-American Convention for the Prevention, Punishment and Eradication of Violence against Women, known as the Convention of Belém do Pará.

Authorities in Roraima—and Brazil as a whole—need to reduce barriers for women in accessing police and ensure that domestic violence cases are properly documented at the time women report them, and then investigated and prosecuted. Authorities need to allocate more resources to training and investigation—and discipline police officers who fail to carry out their duties.

Methodology

This report is based on Human Rights Watch documentation of 31 cases of domestic violence in Roraima, and on interviews with police and justice officials in the state. We conducted interviews in Roraima in February 2017, supplemented by telephone interviews in March and May 2017, with dozens of people, including women experiencing abuse and their relatives; police officers; justice officials from the prosecutor’s office, the public defender’s office, and the court; and members of the Humanitarian Support Center for Women (CHAME, in Portuguese), a center providing legal, psychological, and social support to survivors of domestic violence that is funded by the state legislature. We also reviewed official documentation in most of the 31 cases, including police reports and judicial files. Finally, we consulted published sources and spoke with domestic violence judges, prosecutors, public defenders, and defense lawyers in the states of São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Pernambuco, and Ceará, and several national experts.

We have withheld the names of the women and girls who experienced domestic violence for security reasons, except in the case of Taise Campos, who consented to using her real name. Where we have used pseudonyms, we have indicated so in the relevant citations. We have also removed the exact dates of interviews in some cases to further guard the identity of victims and family members.

All interviewees were informed of the purpose of the interviews and that their interviews would be used in Human Rights Watch publications. No incentives were offered or provided to people interviewed. The interviews were conducted in Portuguese.

Domestic Violence in Brazil

Almost a third of Brazilian girls and women older than 16 said in a February 2017 survey by polling firm Datafolha that they had, during the past year, suffered violence ranging from threats to beatings to attempted killings.[1] In 61 percent of the cases, the attackers were partners, former partners, or other acquaintances of the victim.[2] Only a quarter of women who suffer violence report it, the survey found.[3]

In 2013, a parliamentary inquiry established by Congress published partial nationwide data—the states did not provide all the information requested—that shows, consistent with what Human Rights Watch found in Roraima, significant failures in the state response to domestic violence.[4] Its 1,045-page report said, for instance, that in the state of Ceará no more than 11 percent of domestic violence complaints resulted in investigations;[5] and in the state of Minas Gerais prosecutors filed charges in only 11 percent of the investigations police sent them.[6]

There were 4,521 killings of women in Brazil in 2015.[7] A study based on 2013 Ministry of Health data estimates half of all cases that year were “femicides,”[8] defined in a 2015 law that increases penalties for such crimes as the killing of a woman “on account of her gender.”[9]

Brazil has a comprehensive legal framework, established by the 2006 “Maria da Penha” law,[10] to prevent violence and to ensure justice when it occurs. But implementation is lagging.

The law called for the expansion of women’s police stations and domestic violence units within non-specialized police stations.[11] Such stations and units, however, remain concentrated in major urban centers and serve an average population of 210,000 women each.[12]

A 2015 World Bank study of 2,000 municipalities credited the presence of women’s police stations with a 17 percent drop in the homicide rate of women living in metropolitan areas where such centers were active.[13] And yet, these stations could be even more effective if they were open during hours more conducive to addressing the needs of women: according to the parliamentary inquiry, most are closed during evenings and on weekends, precisely when domestic violence is most likely to occur.[14]

Thanks to the Maria da Penha law, judges can order suspected abusers to stay away from a woman’s home and not to contact her or her family, among other protective measures. But police fail to monitor the vast majority of protection orders.[15]

Domestic Violence in Roraima

Roraima is a state nearly the size of Ecuador, in the far north of Brazil, with a population of only half a million people. The state collects no official data on the prevalence of domestic violence, defined by the Maria da Penha law as any “action or omission”—within a household, family, or intimate relationship—that is based on gender and that causes “death, injury, physical, sexual or psychological suffering, and moral or economic abuse.”[16]

The 31 cases of domestic violence we documented illustrate how it affects women of all socioeconomic classes, ages, and races. In all those cases, women said they had suffered psychological violence. Their abusers had intimidated, insulted, and threatened them repeatedly. In 19 cases, the psychological violence had escalated to physical violence, including five instances of sexual violence. In four cases, women alleged economic abuse, defined by the Maria da Penha law as the retention or destruction of a woman’s property.[17]

Separation was often a critical moment, when the abuse escalated and when women reported seeking state intervention, as a man saw his control over a woman slipping away. Fourteen of the women whose cases we documented said their children witnessed the abuse and at times also suffered it.

Those observations are consistent with findings by large-scale studies in Brazil. For instance, a 2016 survey among 10,000 women in the northeastern states found more than a quarter had suffered domestic violence in their lifetimes, most commonly psychological abuse, and more than half of mothers who endured physical violence said their children witnessed or suffered it. [18]

Failure to Provide Adequate Access to Justice

In most of the 31 cases Human Rights Watch documented, the women had endured many episodes of abuse before reporting to authorities. The reason for not reporting abuse varied: family pressure to maintain a relationship, distress about stigmatization when reporting to police, fear of losing a partner’s financial support for children, or a justifiable belief that reporting to the police would prompt an abuser to carry out threats. When women in Roraima do gather the courage to contact authorities—whether calling the military police or going to a civil police station—the response is often deficient.

Major Miguel Arcanjo Lopes, coordinator of community policing and human rights at Roraima’s Military Police, told Human Rights Watch that in a number of cases, military police fail to send an officer to respond to a woman’s emergency call for help.[19] The force lacks the personnel to respond to all such calls so they choose those that seem most severe, he said. The military police do not provide data on how many calls are received and ignored.

When officers respond to calls for help and they determine the woman has suffered violence, Lopes said, they take the victim and the alleged aggressor to the civil police to register a complaint. If officers conclude that the problem is merely a “disagreement,” they try to reconcile the man and woman, Lopes said. But officers who make that potentially life or death decision receive little or no training.

Captain Cyntya Loureto, coordinator of the Ronda Maria da Penha, a specialized military police unit that responds to 20 percent of the domestic violence calls in Boa Vista, told us that officers who are members of the unit receive only one day of training on responding to domestic violence, ever. Officers from other units receive no such training.[20]

A girl, who we will refer to as “Cláudia” for her safety, told Human Rights Watch that when she made an emergency call to the military police, they ignored her allegations of domestic violence and tried to “reconcile” her with an abuser.[21]

Cláudia became pregnant in February 2016, when she was 13 and her boyfriend was 18, which constituted statutory rape under Brazilian law. They moved in together, and after she gave birth, he hit her on three separate occasions, injuring her in the mouth, eye, and thigh. He also threatened to kill her if she left him. She did not report the abuse because she did not want to raise a child alone. “I cried, just cried, and asked him not to do that to me, but he continued,” Cláudia said.

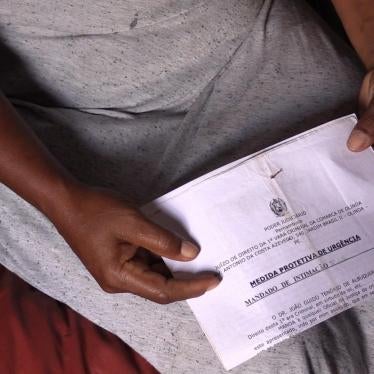

On January 18, 2017, after her boyfriend locked her in their home, Cláudia escaped and, for the first time, called the police. They didn’t come, but she called again and they eventually arrived. She told the officers about the abuse and injuries, and they tried to reconcile her with her boyfriend. Three days later, she fled with the baby to her mother’s house. Her boyfriend smashed the fence and broke into the house. She said he hit her in the ribs, and threatened, again, to kill her. That same day, for the first time, she went in person to the police, with her stepfather. The statement the civil police recorded (pasted below) consists of a single paragraph about the last incident; it makes no allusion to Cláudia’s allegations of prior abuse.

The only women’s police station in Roraima is in Boa Vista—hundreds of miles from some communities in the state—and it serves all 255,000 women in the state.[23] It is open between 7:30 a.m. and 7:30 p.m. on weekdays only. It is closed at night and on Saturday and Sunday, precisely when the Roraima military police told us that violence against women is most likely.[24] When the women’s police station is closed, an officer remains on duty to register complaints, but in fact registers “few,” Elivânia Aguiar, the head of the station, told us.[25] The officer keeps the door of the station locked, and only opens it if someone knocks, Aguiar explained. Military police and civil police from other stations do not send victims to the women’s police station while it is closed. The officer on duty has no authority to request protection orders.

Not a single police station in Roraima provides private rooms for women to make statements, the chief of civil police, Edinéia Chagas, told Human Rights Watch. Even in the women’s police station, women have to tell of abuse, including sexual abuse, in open reception areas.[26]

Many survivors of domestic violence face such a cruel combination of social stigma and profound trauma that failing to provide a private space can deter reporting. As Taise Campos, a teacher who suffered violence, told us, “going to the women’s police station is not good, but going to any other is most horrible, because you are generally speaking in front of many people. … You are so exposed that you feel naked.”[27] Lack of confidentiality could also put women at risk if the abuser learns from others in the station that the survivor has made a statement, and even the specifics of that statement.

According to Brazilian law, women should be able to report domestic violence in any police station, but in Roraima, that is not guaranteed. For example, a domestic violence survivor we’ll call “Priscila” tried to file a complaint on a weekend and a police officer told her to wait until the women’s police station opened on Monday.[28]

Priscila, 42, often suffered beatings and verbal violence from her partner of eight years. Priscila’s 13-year-old daughter, “Lais,” witnessed it. “In the morning, I see the marks of the beatings,” Lais said, “and she always tells me what happened.” Late on Saturday night, December 3, 2016, Priscila’s partner pushed her out of his house, Lais said, and in the middle of the street he hit her in the head, face, and arm. He only stopped when Priscila’s son blocked him. Lais called the military police, who came but did nothing, she said. “They only left their card.” At 3 a.m. on Sunday, Priscila and Lais walked for an hour to reach a non-specialized police station. An officer there told them they had to wait until Monday to report the beating at the women’s police station. On Tuesday, Priscila went to a public event where she had heard that the domestic violence prosecutor would appear. The prosecutor had an official car drive Priscila to the women’s police station, where she reported the beating.

Domestic violence is so complex and dangerous—both to victims and to the officers who intervene—that training is essential for all law enforcement officers. Yet like most military police officers, the civil police officers who record and investigate women’s complaints in Roraima receive no training at all in how to respond to domestic violence, the state civil police chief told Human Rights Watch. Shockingly, even those who work at the women’s police station receive no training.

The lack of training has serious consequences, according to such experts as Lucimara Campaner, the domestic violence prosecutor for the state of Roraima, and Sara Farias, an attorney at CHAME.[29] Some police officers only register domestic violence complaints in cases of physical abuse, they said, and fail to identify other types of violence, such as psychological violence. Worse yet, one victim and various officials mentioned cases in which officers blamed the victim even as they were recording their statements, implying to women who called for help that they had provoked the abuser.

Such lapses, errors, and negligence on the part of civil police go unaddressed. The chief of civil police in Roraima said that she did not know of any civil police officer who had been disciplined for improper treatment of a victim of domestic violence.[30]

Failure to Investigate Domestic Violence

When a woman goes to any civil police station, the police make a report of her complaint. In Boa Vista, the women’s police station registered 2,026 such complaints in 2016.[31] The woman’s police station is in charge of investigating all complaints of domestic violence filed anywhere in the city. In 2016, it opened investigations into only 957 cases.[32]

The women’s police station also compiles the domestic violence complaints registered by the city’s other police stations. Yet the chief of the women’s police station could not tell Human Rights Watch how many complaints had been filed throughout the city.[33] She cited the inadequacy of the police computer system.

A backlog of about 8,400 domestic violence complaints languishes in the women’s police station in Boa Vista, the station’s chief said, because she lacks the personnel to take the “initial investigative steps”—such as interviewing the victim—that would allow police to formally open an investigation. Instead of obtaining all the facts when a victim arrives to file a complaint, the civil police register a brief report (the “boletim de ocorrência”). They assure the victim that they will call her later to return to the police station for a full statement. But the women’s police station is unable to contact all such women for lack of staff, the chief said. No more than 10 police officers and clerks staff each shift, focusing only on what they determine to be most urgent. As a result, some victims never get to give full statements and their complaints go nowhere.

Even when police formally open an investigation, they do not necessarily investigate. By law, police need to send a completed investigation to a prosecutor within 30 days, if a suspect is free, or within 10 days, if detained, but they can request an extension of that deadline.[34] In reality, in thousands of cases under investigation, police ask for extensions for years on end, and many cases are simply closed once the statute of limitations on the crime runs out.

The chief of the women’s police station estimates that the statute of limitations has passed in more than half of the investigations they finish and send on to the domestic violence prosecutor.[35] Similarly, the domestic violence prosecutor said she files more petitions before the judge to close cases, every month, than to charge abusers, most often because the statute of limitations has run out.[36] The prosecutor blames the failure to collect evidence and conclude investigations in a timely manner on a lack of civil police personnel and resources.

The prosecutor said that she also asks the judge to close cases when women who report threats to the police later decide they no longer want the alleged abuser to be prosecuted. Explicit consent is necessary to prosecute threats under Brazilian law. The prosecutor said that some women withdraw their consent because the couple has reconciled; others do so in response to pressure by the alleged aggressor’s family or because they depend financially on the alleged aggressor. Although the prosecutor did not have exact data, she said that she asks to have more cases closed because the statute of limitations has run out than because the women withdrew their consent to move forward with the case.

The Boa Vista District domestic violence court handles all domestic violence investigations except femicides and attempted femicides, which go to the homicide court. Of the 5,000 active domestic violence investigations reported to us by the Boa Vista court, more than half—2,885—are of incidents from 2013 or earlier.[37] That means, for example, that the three-year statute of limitations on the crime of threat—very common in domestic violence cases—has expired. Almost 10 percent of the investigations—482—are of incidents that occurred from 2007 through 2010.[38] All of those have either expired or are about to do so, because the statute of limitations for most cases of bodily injury, the gravest crime dealt with by the domestic violence court, is eight years.[39]

The failure to investigate domestic violence cases is even more appalling because, unlike with many other crimes, the alleged perpetrator is known. Victims often provide an abuser’s contact information, and they often provide physical exams, records of threatening messages, and the contact information of possible witnesses. But civil police often fail to follow up.[40]

The life of schoolteacher Taise Campos, 38, changed radically 11 years ago when her husband started drinking and becoming aggressive.[41] He verbally abused her, broke religious images and other objects that were dear to her, and beat her in front of their two children, Campos told Human Rights Watch. He would lock Campos and the children in a room for hours, she said. And yet, she never filed a police report. “I did not seek out the authorities because I hoped that with prayer and perseverance, I could reverse the decline,” she said. But the abuse never stopped. The couple divorced in 2010, but Campos’s ex-husband continued to threaten her. “He was always sending me very aggressive text messages to threaten me: ‘You are not protected. You can be shot at anytime. It may take 10, 15, 20 years, but one day I’ll kill you.’” Finally, she went to the authorities, she said, filing more than 15 police reports, as years of abuse dragged on. She said she provided evidence to support her complaints. She left her cell phone at the civil police station for analysis—for a year and a half. Yet the statute of limitations on each crime she alleged has expired. Campos has challenged the court’s decision to close the case.

In most of the almost 900 domestic violence incidents in which the prosecutor has filed charges and are now pending trial in Boa Vista, the prosecutor told us that police caught the suspect in the act of abuse. [42] In those cases, law enforcement personnel take the suspect and the victim to the police station, where they make full statements and they undergo medical exams. Unlike the majority of domestic violence cases—in which police do not take a full statement from the victim right away—cases in which police catch perpetrators in the act of abuse move forward because police collect key evidence at the moment of arrest.

By failing to investigate and prosecute most domestic violence cases, the state permits an atmosphere of impunity for these crimes, allowing for an escalation of violence, common in abusive relationships, that can lead to a woman’s death. “In 100 percent of cases, there is information about prior violence,” Paulo André Trindade, one of the two homicide prosecutors in Boa Vista, said of femicide.[43] “The level of aggression evolves from psychological violence to physical violence and homicide.”

The Boa Vista homicide prosecutor’s office had no data on the percentage of killings or attempted killings of women that have resulted in convictions. When cases get to trial, Trindade said, they often result in convictions. Yet sloppy police work can be a problem all along the way. Military police sometimes do not preserve the crime scene, he said, and forensic experts do not do adequate analysis, or any at all. Shoddy investigative work impeded justice, for example, in the case of 16-year-old Cleiciane Sabino da Silva.[44]

Da Silva was beaten to death with a hammer on November 5, 2012 in a rural area of Urubuzinho. Her 31-year-old husband and his three friends had been drinking, police said, and after two of the friends left to buy more alcohol and Da Silva’s husband passed out from drinking, the third friend, Wydeglan Falcão, 22, raped her and beat her to death. Falcão fled and was captured two years later.[45] He was acquitted in November 2016 because of what the prosecutor called blatant failures of forensic analysis.[46] Forensic experts had failed to take pictures of the crime scene, failed to collect fingerprints, and failed to collect semen properly—making DNA analysis impossible.

Barriers to Requesting Protection Orders

A crucial contribution of the Maria da Penha law was the creation of protection orders, which the United Nations Handbook for Legislation on Violence against Women considers “among the most effective legal remedies” available to women.[47]

Among other measures, the law allows judges to order suspected abusers to stay away from a woman’s home and not to approach or contact her or her relatives.[48] Men who violate a protection order can be punished with fines, and judges can find that the violation is grounds for pretrial detention.[49]

Any chief police officer (“delegado”) in Brazil can request that a judge grant a protection order on behalf of a woman or girl who has been abused. But just as in the filing of domestic violence complaints as a whole, officers in some police stations in Boa Vista erroneously tell victims that they need to go to the women’s police station to seek a protection order. Once again, the closure of the women’s police station on weekends and at night means that women in danger may have to wait more than two days to request a protection order. Fifty percent more women appear at the station to file complaints or request protection orders on Mondays than on other days, the chief of the station told Human Rights Watch—proof of the dangerous weekend wait-time.[50] Such restriction of reporting runs counter to the purpose of protection orders, which are intended as emergency measures, when speed is essential to preventing continuing violence.

Cláudia, the 14-year-old mother mentioned earlier, went to a non-specialized police station closer to her home than the women’s station after suffering several beatings by her boyfriend.[51] An officer made a police report only of the most recent incident and told her she would have to go to the women’s police station to request a protection order. It was Saturday, the women’s station was closed, and Cláudia spent several days in terror that her boyfriend would return to hit her. She finally made a two-hour trip by foot and bus to the women’s police station and requested a protection order, which a judge granted. When Human Rights Watch interviewed Cláudia days later, she was living at her mother’s house, where her boyfriend had previously broken in to abuse her. Since the order was issued, she said, her boyfriend had not come looking for her.

Unlike Cláudia, some women and girls may give up after being turned away from the first station where they seek a protection order. Lack of transportation money, shame at having to repeat their story in public, and fear of improper police treatment are all deterrents.

Failure in Processing Protection Orders

Human Rights Watch found that police officers, especially at non-specialized stations, sometimes fail to record information when taking a woman’s statement that is key to characterizing the nature of the abuse. That makes it difficult for judges to deliver an informed decision as to whether a woman requires a protective order. “In 60 percent of police reports, there is information missing,” a law clerk at the domestic violence court said.[52]

When key information is missing, a domestic violence judge asks the public defender’s office to re-interview the woman seeking the protection order. In such cases, women have to appear at the public defender’s office; the office does not have the resources to interview women at home.

Repeating the interview delays the issuance of protection orders, often for weeks, at a moment when women are most at risk of renewed violence. Worse, in some cases, the domestic violence public defender is unable to arrange a repeat interview.[53] Women often change their phone numbers to protect themselves from abusers. When staff cannot make contact to re-do a flawed interview, a protection order is never issued and a woman is left in danger.

The difference between victims’ statements taken by police–even at the women’s police station–and by the domestic violence public defender is striking. The public defender, who provides legal representation to women, usually describes the context of the violence, details past abuses and threats, and typically renders more than two-and-a-half pages of text. She also describes actions that may not constitute crimes but that are consistent with the definitions of violence outlined in the Maria da Penha law and characterize an abusive relationship, such as a man’s attempts to control what a woman does or where she is or his refusal to accept the end of a relationship. The statements contained in police reports that we examined consisted of two paragraphs, at most. At times, they failed to include information critical to understanding patterns of abuse.

In the case of 22-year-old “Maria,” police described her abuse as a couple’s fight, neglected to note prior abuse, and failed to mention whether Maria had requested a protection order at the time she filed the complaint.[54]

Maria went to the women’s police station on December 20, 2016, to report abuse by her 24-year-old husband. They had been together since she was 15, and had one child. They had a “dispute” in the early hours of December 20, as the police report below phrased it, during which Maria’s husband swore at her, threatened her, and hit her in the face and on the arms and legs. Maria hit back, “to defend herself,” the report noted, but it added that they did not fight often, though Maria’s husband was “very jealous.” In the morning, Maria asked her husband to leave, and when he refused, she took the child and moved in with her mother.

(Names of the victim and her husband redacted by Human Rights Watch)[55]

In contrast, a petition for a protection order that the public defender filed 23 days later on Maria’s behalf detailed that she had suffered “constant verbal violence” for three years and lived “always in fear” of her husband. After the beating on December 20, the petition noted, she went to the women’s police station to “request a protection order” and to have a physical exam that would show the bruising. Maria’s husband still threatens her constantly, the petition notes, demanding that she come back to him.

Insufficient Monitoring of Protection Orders

The domestic violence court in Boa Vista, the only one in Roraima, said that in February 2017 there were 600 women under protection orders in its district.[56] It did not have statewide data.

Until September 2015, police did not monitor compliance with protection orders in Roraima. Since then, the domestic violence court and the municipal government of Boa Vista only—not the rest of the state—have followed the example of a handful of other Brazilian cities, setting up a Maria da Penha patrol to monitor the most serious cases, as determined by the staff of the judge who issues the protective orders.

The patrol is staffed by 11 municipal guards who visit as many as 12 women daily. During the first month that an order is active, they see a woman three times a week, unless she declines the visits. Afterwards, they stop visiting. If the woman reports that an aggressor has violated the protection order, the municipal guards write a report about the violation that is added to the case file. The prosecutor, judge, and public defender said such reports were extremely helpful—and used in legal proceedings.

Police do not, however, monitor protection orders that are not selected by the staff of the domestic violence judge in Boa Vista or issued by other judges outside of the capital.

Recommendations

In 1991, Human Rights Watch published a report on domestic violence in Brazil.[57] Since then, the country has made important progress, particularly with the approval of the Maria da Penha law in 2006. In recent years, the federal government has invested in the construction of joint facilities known as “Brazilian Women’s Houses,” housing women’s police stations, domestic violence prosecutors, public defenders, and judges, as well as support services for victims. One such facility was slated to open in Boa Vista in 2014 and is only now nearing completion.[58]

Still, Roraima—and all of Brazil—need to do much more to address the chronic problem of domestic violence. To understand its scope, the police and justice system in Roraima and every other state should start collecting and publishing comprehensive data on the number of police complaints, investigations, cases in which charges are filed, and trials and their outcomes, as well as the number of killings of women and how many are suspected femicides, as defined by Brazilian law.

It is crucial that authorities reduce barriers women and girls face in filing complaints. To do so, Roraima should expand its women’s police station–in personnel and in regular operating hours. State authorities should ensure all police stations have rooms to provide privacy and confidentiality to victims. Civil police officers should take victims’ full statements when they first arrive at any station and should then carry out prompt and thorough investigations of all complaints.

Meeting such basic standards will require specialized training for military and civil police officers who handle domestic violence cases, the development of detailed written protocols about how to respond to emergency calls, and how to record and process women’s complaints and requests for protection orders.

The Internal Affairs departments should discipline officers who fail to abide by internal rules and protocols, and by the Maria da Penha law and other legislation, when dealing with domestic violence cases. Public defenders and, above all, prosecutors, should inform Internal Affairs departments of police misconduct.

In addition, the public defender’s office should designate at least one more public defender to represent women in domestic violence cases, especially those who live outside of Boa Vista and who currently would have to travel to the capital for those services.

Finally, justice officials in Roraima should work with state and municipal authorities to ensure that municipal guards or the military police monitor each and every protection order.

Acknowledgments

This report was written by César Muñoz Acebes, based on research conducted by César Muñoz Acebes and Tamara Taraciuk Broner, senior researchers in the Americas Division. It was reviewed and edited by Daniel Wilkinson, managing director of the Americas division; Margaret Knox, senior editor/researcher; Dan Baum, senior editor/researcher; Amanda Klasing, senior researcher in the Women’s Rights Division; Maria Laura Canineu, Brazil director; Bede Sheppard, deputy director of the Children’s Rights Division; Christopher Albin-Lackey, senior legal advisor; and Joseph Saunders, deputy program director. Andrea Carvalho, consultant in the Americas Division, provided research support. Hugo Arruda, Brazil acting senior manager, and Kate Segal, senior Americas associate, provided logistical and editing support. The report was prepared for publication by Olivia Hunter, publications associate, Fitzroy Hepkins, administrative manager, and Jose Martinez, senior coordinator.

Human Rights Watch would like to thank prosecutor Lucimara Campaner, public defender Jeane Xaud, judge Sissi Marlene Schwantes, and their staff; the Humanitarian Support Center for Women (CHAME, in Portuguese); the civil and military police of the state of Roraima; and the Boa Vista municipal guards of the Maria da Penha Patrol for providing insights and information for this report.

Most importantly, we are deeply grateful to the women who so generously shared their stories with us. We are especially thankful to Taise Campos, a survivor of domestic violence whose courage inspires us.