(São Paulo) – The authorities in the Brazilian state of Roraima are failing to investigate or prosecute domestic violence cases, leaving women at further risk of abuse, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today. The serious problems in Roraima, the state with the highest rate of killings of women in Brazil, reflect nationwide failures to provide victims of domestic violence with access to justice and protection.

The 22-page report, “‘One Day I´ll Kill You’: Impunity in Domestic Violence Cases in the Brazilian State of Roraima,” examines systemic problems in responding to domestic violence in the state. Human Rights Watch documented 31 cases of domestic violence, and interviewed victims, police, and justice officials. The organization found failures at all points in the system for responding to domestic abuse.

“Many women in Roraima suffer violent attacks and abuse for years before they summon the courage to report it to the police, and when they do, the government’s response is dreadful,” said Maria Laura Canineu, Brazil director at Human Rights Watch. “As long as victims of domestic violence can’t get help and justice, their abusers will keep right on injuring and killing them.”

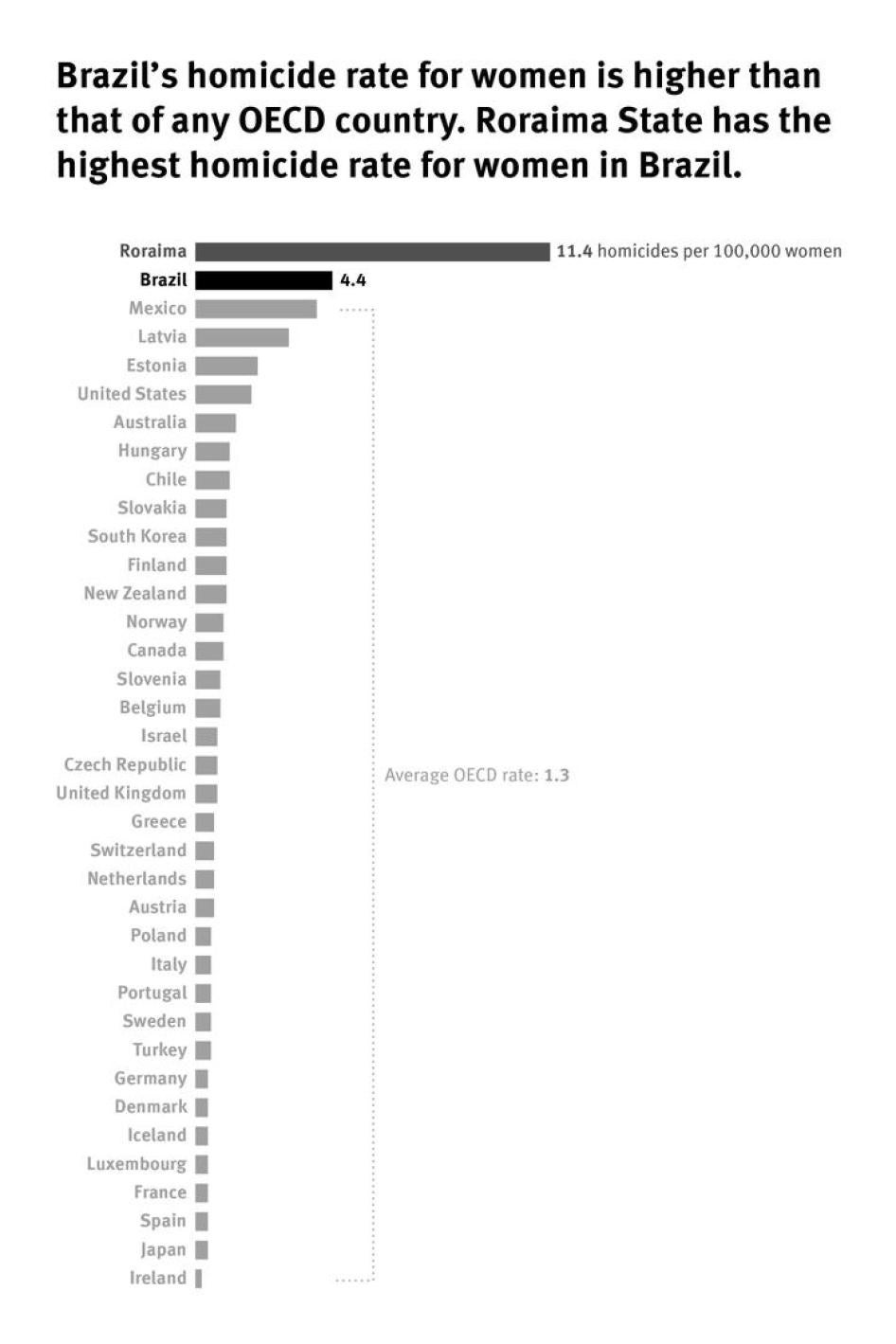

Killings of women rose 139 percent from 2010 to 2015 in Roraima, reaching 11.4 homicides per 100,000 women that year, the latest for which there is data available. The national average is 4.4 killings per 100,000 women—already one of the highest in the world. Studies in Brazil and worldwide estimate that a large percentage of women who suffer violent deaths are killed by partners or former partners.

Only a quarter of women who suffer violence in Brazil report it, according to a February 2017 survey that does not provide state-by-state data. Human Rights Watch found in Roraima that when women do call police they face considerable barriers to having their cases heard.

Military police told Human Rights Watch that, for lack of personnel, they do not respond to all emergency calls from women who say they are experiencing domestic violence. Other women are turned away at police stations. Some civil police officers in Boa Vista, the state´s capital, decline to register domestic violence complaints or request protection orders themselves, Human Rights Watch found. Instead, they direct victims to the single “women’s police station” in the state—which specializes in crimes against women—even at times when that station is closed.

Even when police receive their complaints, women must tell their story of abuse, including sexual abuse, in open reception areas, as there are no private rooms to take statements in any police station in the state.

Not a single civil police officer in Roraima receives training in how to handle domestic violence cases. And it shows, Human Rights Watch found. Some police officers, when receiving women seeking protection orders, take statements so carelessly that judges lack the basic information they need to decide whether to issue the order.

Civil police are unable to keep up with the volume of complaints they do receive. In Boa Vista, the police have failed to do investigative work on a backlog of 8,400 domestic violence complaints. Most cases languish for years until they are eventually closed because the statute of limitations on the crime expires–without any prosecution, according to the police.

Taise Campos, a 38-year-old teacher, filed more than 15 police complaints, she told Human Rights Watch, to report repeated acts of physical and verbal abuse by her former husband. But the statute of limitations expired before he could be tried for the alleged crimes. “A person who needs help loses all faith in the justice system,” Campos said.

Brazil has a comprehensive legal framework, established by the 2006 “Maria da Penha” law, to prevent domestic violence and to ensure justice when it occurs. But implementation of many of its provisions is lagging.

The law, named after a victim who filed a case with the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights over the lack of response to her case by authorities in Brazil, called for the expansion of women’s police stations and domestic violence units within non-specialized police stations. But these units remain concentrated in major cities and are often very hard to reach for women who live in other areas. Women’s police stations are also badly overburdened, serving an average population of 210,000 women each.

The law also allows judges to order suspected abusers to stay away from a woman’s home and not to contact her or her family, among other protective measures. But police fail to monitor the vast majority of protection orders.

Authorities in Roraima—and Brazil as a whole—need to reduce barriers for women to filing complaints with police, Human Rights Watch said. And the authorities should ensure that domestic violence cases are properly documented at the time women report them, and then investigated and prosecuted. The authorities also need to allocate more resources to training and investigation—and discipline police officers who fail to carry out their duties.

“While Roraima has the highest rate of killings of women in the country, the problems there are symptomatic of the failure to protect women from abuse nationwide,” Canineu said. “The Maria da Penha law was a major step forward, but more than a decade later, implementation remains woefully inadequate throughout much of the country.”