Summary

When the head teacher found out that I was pregnant, he called me to his office and told me, “You have to leave our school immediately because you are pregnant.”

—Jamida K., Kahama, Tanzania, April 2014

We don’t allow pregnant girls to continue with school. We ask her to go home and return after the baby is born. If she attends pregnant, she can be ridiculed by other students and be a bad influence.

—Kenneth Tengani Malemia, deputy head teacher, Dyeratu Primary School, Chikwawa district, Malawi, September 2013

The African continent has the highest adolescent pregnancy rates in the world, according to the United Nations. Every year, thousands of girls become pregnant at the time when they should be learning history, algebra, and life skills. Adolescent girls who have early and unintended pregnancies face many social and financial barriers to continuing with formal education.

All girls have a right to education regardless of their pregnancy, marital or motherhood status. The right of pregnant—and sometimes married—girls to continue their education has evoked emotionally charged discussions across African Union member states in recent years. These debates often focus on arguments around “morality,” that pregnancy outside wedlock is morally wrong, emanating from personal opinions and experiences, and wide-ranging interpretations of religious teachings about sex outside of marriage. The effect of this discourse is that pregnant girls – and to a smaller extent, school boys who impregnate girls– have faced all kinds of punishments, including discriminatory practices that deny girls the enjoyment of their right to education. In some of the countries researched for this report, education is regarded as a privilege that can be withdrawn as a punishment.

But the international legal obligation of all governments to provide all children with an education, without discrimination, is clear.

In 2013, all the countries that make up the African Union (AU) adopted Agenda 2063, a continent-wide economic and social development strategy. Under this strategy, African governments committed to build Africa’s “human capital,” which it terms “its most precious resource,” through sustained investments in education, including “elimination of gender disparities at all levels of education.” Two years after the adoption of Agenda 2063, African governments joined other countries in adopting the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), a development agenda whose focus is to ensure that “no one is left behind,” including a promise to ensure inclusive and quality education for all. African governments have also adopted ambitious goals to end child marriage, introduce comprehensive sexuality and reproductive health education, and address the very high rates of teenage pregnancy across the continent that negatively affect girls’ education.

Yet many AU member states will fail in this promise if they continue to exclude tens of thousands of girls from education because they are pregnant or married. Although all AU countries have made human rights commitments to protect pregnant girls and adolescent mothers’ right to education, in practice adolescent mothers are treated very differently depending on which country they live in.

A growing number of AU governments have adopted laws and policies that protect adolescent girls’ right to stay in school during pregnancy and motherhood. There are good policies and practices to point to, and indeed, far more countries protect young mothers’ right to education in national law or policy than discriminate against them. These countries can encourage countries that lack adequate policies, and particularly persuade the minority of countries that have adopted or encouraged punitive and discriminatory measures against adolescent mothers to adopt human rights compliant policies.

This report provides information on the status of laws, policies, and practices that block or support pregnant or married girls’ access to education. It also provides recommendations for much-needed reforms.

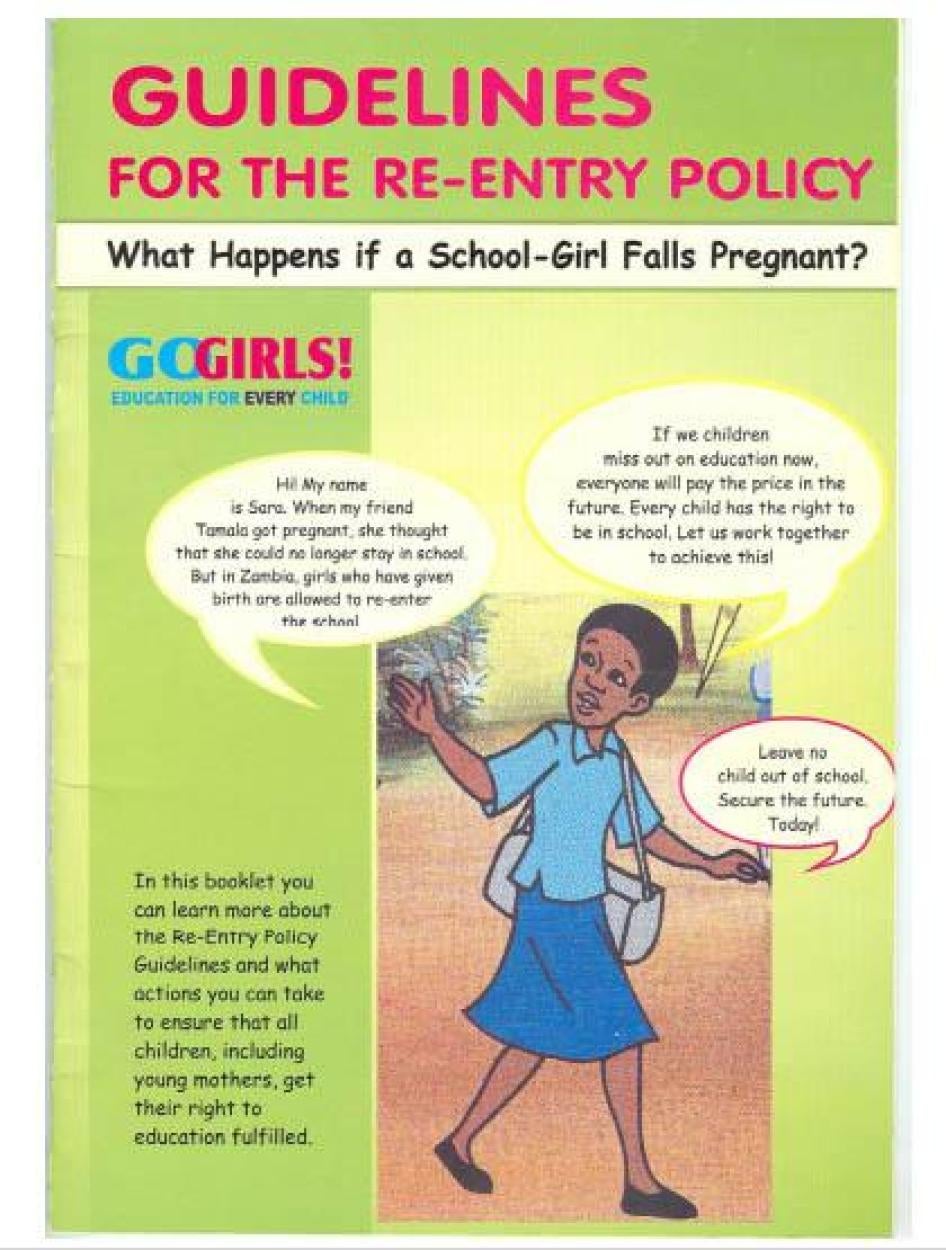

Gabon, Kenya, and Malawi are among the group of 26 African countries that have adopted “continuation” or “re-entry” policies, and strategies, to ensure that pregnant girls can resume their education after giving birth. However, implementation and adherence vary across these countries, especially regarding the length of time the girl should be absent from school, the processes for withdrawal and re-entry, and available support structures within schools and communities for adolescent mothers to remain in school.

Although the trend of more governments opting to keep adolescent mothers in school is strong, implementation of their laws and policies frequently falls short, and monitoring of adolescent mothers’ re-entry to education remains weak overall. There are also concerns about punitive and harmful aspects of some policies. For example, some governments do not apply a “continuation policy” for re-entry – where a pregnant student would be allowed to remain in school for as long as she chooses to. Long periods of maternity leave, complex re-entry processes such as those that require medical certification, as in Senegal, or letters to various education officials in Malawi, or stringent conditions that girls apply for readmission to a different school, can negatively affect adolescent mothers’ willingness to return to school or ability to catch up with learning.

Many other factors contribute to thousands of adolescent mothers not continuing formal education. High among them is the lack of awareness about re-entry policies among communities, girls, teachers, and school officials that girls can and should go back to school. Girls are most often deeply affected by financial barriers, the lack of support, and high stigma in communities and schools alike.

Some governments have focused on tackling these barriers, as well as the root causes of teenage pregnancies and school dropouts, for example by:

- Removing primary and secondary school fees to ensure all students can access school equally, and targeting financial support for girls at risk of dropping out through girls’ education strategies, as in Rwanda;

- Providing social and financial support for adolescent mothers, as in South Africa;

- Providing special accommodations for young mothers at school, for instance time for breast-feeding or time off when babies are ill or to attend health clinics, as in Cape Verde and Senegal;

- Providing girls with a choice of access to morning or evening shifts, as in Zambia;

- Establishing nurseries or early childhood centers close to schools, as in Gabon;

- Providing school-based counselling services for pregnant girls and adolescent mothers, as in Malawi; and

- Facilitating access to sexual and reproductive health services, including comprehensive sexuality education at school and in the community, as in Ivory Coast, and access to a range of contraceptive methods, and in South Africa, safe and legal abortion.

Despite these positive steps by some African countries, a significant number still impose laws and policies that directly discriminate against pregnant girls and adolescent mothers in education. For example, Equatorial Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Tanzania expel pregnant girls from school and deny adolescent mothers the right to study in public schools. In most cases, such policies end a girl’s chances of ever going back to school, and expose her and her children to child marriage, hardship, and abuse. In practice, girls are expelled, but not the boys responsible for the pregnancy where they are also in school.

Human Rights Watch also found that 24 African countries lack a re-entry policy or law to protect pregnant girls’ right to education, which leads to irregular enforcement of compulsory education at the school level. We found that countries in northern Africa generally lack policies related to the treatment of teenage pregnancies in school, but in parallel, impose heavy penalties and punishments on girls and women who are reported to have had sexual relationships outside wedlock. Countries such as Morocco and Sudan, for example, apply morality laws that allow them to criminally charge adolescent girls with adultery, indecency, or extra-marital sex.

Some countries resort to harmful means to identify pregnant girls, and sometimes stigmatize and publicly shame them. Some conduct mandatory pregnancy tests on girls, either as part of official government policy or individual school practice. These tests are usually done without the consent of girls and infringe on their right to privacy and dignity. Some girls fear such humiliation that they will preemptively drop out of school when they find out they are pregnant, while others will go to great lengths to procure unsafe abortions, putting their health and lives at risk.

Government policies that discriminate against girls on the basis of pregnancy or marriage violate their international and regional human rights obligations, and often contravene national laws and constitutional rights and undermine national development agendas.

Leaving pregnant girls and adolescent mothers behind is harmful to the continent’s development. Leaving no one behind means that African governments should recommit to their inclusive development goals and human rights obligations toward all children, and ensure they adopt human rights compliant policies at the national and local levels to protect pregnant and adolescent mothers’ right to education. Early and unintended pregnancies jeopardize educational attainment for thousands of girls. For this reason, governments need to prevent them by ensuring their educational institutions provide knowledge, information, and skills, so that pregnant girls and adolescent mothers can enjoy their right to continue their education.

Recommendations

To All African Union Governments

Immediately End Pregnancy-Based Discrimination in Schools in Policy and Practice

- End, in policy and practice, the expulsion of female students who become pregnant or get married and provide accommodations for pregnant and married students in schools.

- Immediately end pregnancy testing in schools.

- Ensure cases of sexual harassment and abuse, including by bus drivers, teachers, or school officials, are reported to appropriate enforcement authorities, including police, and that cases are duly investigated and prosecuted.

Ensure Pregnant Students and Young Mothers Can Resume Education

- Immediately adopt positive re-entry policies and expedite regulations that facilitate pregnant girls and young mothers of school-going age returning to primary and secondary school.

- Ensure that pregnant and married students who wish to continue their education can do so in an environment free from stigma and discrimination, including by allowing female students to choose an alternative school, and monitor schools’ compliance.

- Link pregnant, married and student mothers to health services, such as family planning clinics.

- Introduce formal flexible school programs, including evening classes or part-time classes, for girls who are not able to attend full-time classes, and ensure students receive full accreditation and certificates of secondary education upon completion.

- Include adolescent mothers in programs that target female students at risk of dropping out, and ensure targeted programs include measures to provide financial assistance to at risk students, counselling, school grants, and distribution of inclusive educational materials and sanitation facilities, including menstrual hygiene management kits in schools.

- Expand options for childcare and early childhood development centers for children of adolescent mothers so that girls of school-going age can attend school.

- Ensure that humanitarian education responses in conflict contexts include the particular needs of pregnant girls and young mothers of school-going age.

- Provide access to information to parents, guardians, and community leaders about the harmful physical, educational, and psychological effects of adolescent pregnancy and the importance of pregnant girls and young mother continuing with school.

- Provide school-based counselling services for students who are pregnant, married or mothers. Provide long-term psychosocial support to adolescent survivors of sexual abuse and harassment.

- Engage with teachers and other education officials to support the education of pregnant girls and adolescent mothers, and to ensure they guarantee a safe school environment.

- Improve Data and Monitor Implementation of School Policies on Pregnant Students. Schools should:

- Improve monitoring and data collection on girls who drop out of school due to pregnancy or marriage;

- Develop and implement mechanisms to follow up on and keep track of girls who drop out of school due to pregnancy or marriage, with the aim of initiating their return to school;

- Monitor implementation of school re-entry policies by keeping data on the number of pregnant and married students who get readmitted, their school attendance and completion rates; and use the information to improve support for pregnant, married, and student mothers.

Urgently Tackle Barriers that Impede Girls’ Education

- Ensure primary education is genuinely free by removing tuition fees, and treat access to free secondary education as an urgent and immediate priority rather than as a goal to be realized progressively over time. Take steps to address the indirect costs of primary and secondary schooling.

- Raise the minimum age for marriage to 18 for both boys and girls and take all necessary measures to eliminate child marriages in law and practice, including by implementing comprehensive and well-resourced national strategies for combating child marriage, and sharing best practices.

- Implement nationwide programs to empower girls to attend school. Design programs tailored to local communities that respond to children’s needs and aim to build their skills on a range of issues, including: awareness about sexual and reproductive health, menstrual hygiene management, awareness about sexual consent, sexual violence, and child marriage, as well as mechanisms for reporting any abuse and obtaining assistance.

- Implement public information campaigns directed at families, community leaders, and adolescent boys and girls that address the stigma around teenage pregnancy, sexuality, and reproduction, and discuss the importance of sex education and promote ways for parents to talk about healthy sexual practices.

Guarantee Young People’s Sexual and Reproductive Rights

- Include mandatory sexual and reproductive health education as a stand-alone, examinable subject in the primary and secondary school curriculum.

- Ensure that the mandatory national curriculum on sexuality and reproductive health complies with international standards and that it:

- Includes comprehensive information on sexuality and reproductive health, including information on sexual and reproductive health and rights, responsible sexual behavior, and prevention of early pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections. Include information and skills related to gender equality, the ability to form healthy relationships, consent to sex and marriage and the difference, and prevention of sexual and gender-based violence, including avenues for reporting and redress;

- Is mandatory, age-appropriate, and scientifically accurate;

- Include modules appropriate for teaching in primary school; and

- Is informed by consultations with young people.

- Adequately train teachers to teach the curriculum impartially.

- Ensure that sexual and reproductive health education and information is accessible to students with disabilities and is available in accessible formats such as braille or easy-to-understand formats.

- Adopt laws that set out the minimum age of consent to sexual activity and access to sexual and reproductive health services, equal for adolescent boys and girls, in accordance with international human rights norms and best practice.

- Ensure adolescents can access community-based health services that are adolescent-friendly and ensure they can access accurate information and appropriate contraception to curb teenage pregnancies, HIV, and sexually transmitted diseases. Third party permission for accessing these services should not be required and member states should strive to ensure that user fees are not charged for contraception.

- Ensure health centers do not stigmatize adolescents who are sexually active, and that they are staffed with medical personnel qualified to provide confidential and comprehensive adolescent health services.

- Take all necessary steps, both immediate and incremental, to decriminalize abortion and ensure that adolescent girls and young women have informed and free access to safe and legal abortion services as an element of their exercise of their reproductive and other human rights.

To the African Union

- Call on member states to end pregnancy-based discrimination in schools and related abuses, including mandatory pregnancy testing.

- Consider conducting a continental campaign to support education for pregnant and married girls and adolescent mothers. Such a campaign would build on achievements of the Campaign to End Child Marriage in Africa and the African Youth Decade Plan of Action, as well as other regional initiatives including the Campaign for Accelerated Reduction of Maternal Mortality in Africa (CARMMA), the African Women’s Decade and the Continental Education Strategy for Africa 2016 – 2025 (CESA 16-25).

- Conduct a comprehensive study on existing laws, policies, and practices that support or block education for pregnant and married girls and adolescent mothers among African Union member states, with the aim of facilitating a coordinated and comprehensive approach among countries and sharing of good practices.

- Develop a human rights compliant model re-entry policy and guidelines for governments to adhere to while developing laws, policies, or guidelines to support education for pregnant and married girls and adolescent mothers at national and local levels. Encourage governments to adopt progressive policies that permit pregnant students to remain in school for as long as they choose to, and not prescribe a rigid compulsory leave after giving birth.

African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights and the African Committee of Experts on the Rights and Welfare of the Child

- Call on governments to repeal legislation and policies that discriminate against pregnant girls and adolescent mothers, including criminal laws that impose heavy criminal charges for sex outside marriage.

- Monitor governments’ compliance around implementation of policies to support education for pregnant and married girls, and adolescent mothers during government’s reviews under the relevant human rights instruments.

To Development Partners and UN Agencies

- Urge African Union member states to comply with their international and regional human rights obligations. In particular, urge and support governments, through technical and financial assistance, to:

- End, in policy and practice, the expulsion from schools of female students who become pregnant or get married and immediately end pregnancy testing in schools wherever it is practiced.

- Expedite the adoption of human rights compliant continuation and re-entry policies for parents of school-going age. Encourage governments to adopt progressive policies that permit pregnant students to remain in school for as long as they would like, and not require compulsory leave after giving birth.

- Introduce a mandatory comprehensive sexuality education curriculum in primary and secondary schools that complies with international human rights standards; implement this curriculum as an examinable, independent subject.

- Financially and technically support a comprehensive study on existing laws, policies and practices that support or block education for pregnant and married girls and adolescent mothers among African Union member states, with the aim of facilitating a coordinated and comprehensive approach among countries and sharing of good practices.

- Support the development of a human rights compliant model policy and guidelines for governments to adhere to in developing policies or guidelines to support education for pregnant and married girls and adolescent mothers at national and local levels.

- Ensure primary education is genuinely free by removing tuition fees, and access to free secondary education is treated as an urgent and immediate priority rather than as a goal to be realized progressively over time. Support governments to take steps to address the indirect costs of primary and secondary schooling.

Methodology

Human Rights Watch conducted a study of laws, policies and practices related to pregnant adolescents in education in all member states of the African Union. We also reviewed governments’ education, health, and reproductive health sector strategies and reports, academic research, analysis of laws and practice conducted by national and international organizations on this topic, as well as newspaper articles.

Human Rights Watch contacted six ministries of education and/or country delegations to the United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), including Angola, Djibouti, Equatorial Guinea, Ivory Coast, and Mali, to seek official responses on policies and practices applicable in these countries. We also consulted national and regional civil society organizations working on girls’ education and health.

The report includes testimony from pregnant girls and adolescent mothers interviewed by Human Rights Watch in Malawi, Senegal, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe. It draws on Human Rights Watch’s extensive research on the rights of girls in Africa, including abuses related to child marriage, barriers to girls’ primary and secondary education, sexual and gender-based violence, and access to sexual and reproductive health and rights.[1]

I. Background: Adolescent Pregnancy

and Girls’ Education in Africa

I fell pregnant last year when I was 14 years old. I had stopped going to school that same year because my mother … could not afford to send me to school. I had an affair with an older man who had a wife. I received no sex education at all, and when I had sex with this man I fell pregnant. I wish to go back to school because I am still a child.

—Abigail C., 15, Zimbabwe, October 2015

Adolescent Pregnancy in Africa

Adolescent pregnancy has been stubbornly high in sub-Saharan Africa, which has the world’s highest prevalence.[2] Every year thousands of African girls become pregnant right at the time they should be learning history, algebra, and life skills.[3] Girls from poor and more marginalized households and communities are among the most affected.[4]

The main causes of teenage pregnancy in Africa include sexual exploitation and abuse, poverty, lack of information about sexuality and reproduction, and lack of access to services such as family planning and modern contraception.[5] Many of these pregnancies are unplanned and many happen in the context of child marriages, a big problem in the continent. About 38 percent of girls in sub-Saharan Africa are married before the age of 18 and 12 percent before age 15.[6] African countries account for 15 of the 20 countries with the highest rates of child marriage globally.[7] Yet many African Union governments have failed to adopt a minimum age of marriage of 18 to help protect girls against this abuse and uphold their rights to and through education.[8]

Stigma around Adolescent Sex and Pregnancy Outside Marriage

In many African countries, education and health personnel often shame, stigmatize and sometimes isolate adolescent girls who have early and unintended pregnancies. Condemnation by political leaders or in the media can encourage and exacerbate their stigmatization. Such girls also face increased vulnerability to violence and abuse, or greater poverty and economic hardship.[9]

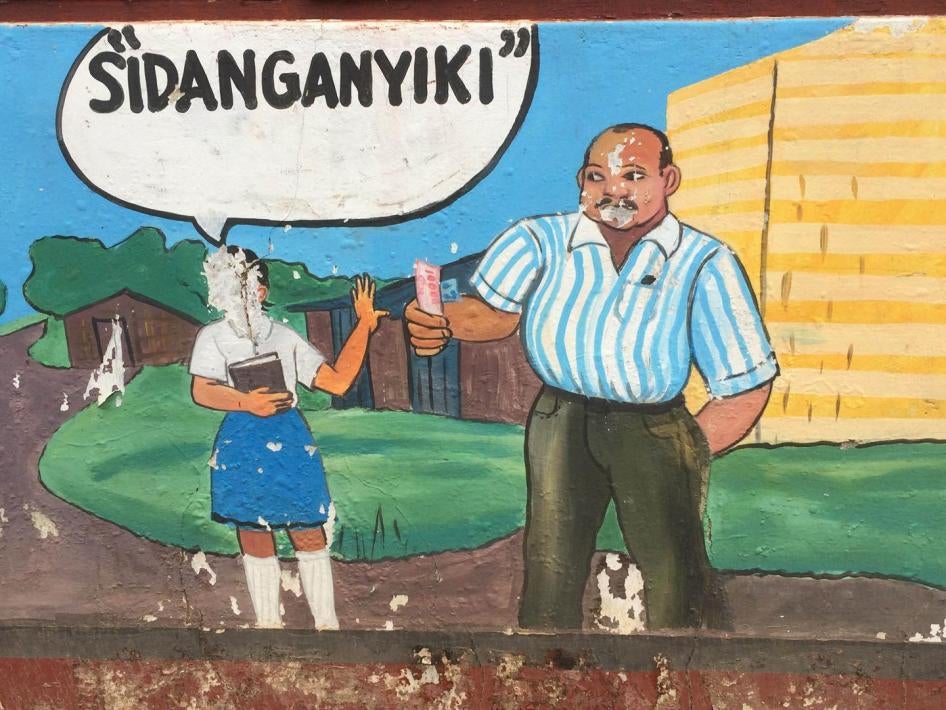

When it comes to schooling, some governments use morality-based arguments to exclude pregnant girls and young mothers. Allowing them to continue their education, the argument goes, will normalize out-of-wedlock pregnancy, absolve the girls of punishment, and create a “domino effect” by which more girls become pregnant. [10]Such arguments are not grounded in any authoritative studies.[11] In Malawi, Senegal, South Sudan and Tanzania, girls who spoke to Human Rights Watch said that they were committed to their education, and are already fully aware of the difficulty of becoming a young mother without additional penalties being imposed.

Deficient Information and Education on Sexuality and Reproduction for Adolescents

From a young age, many children are exposed to conflicting or negative ideas about sexuality at home or at school. During puberty, families, communities, and schools may especially impose stereotypical expectations of boys’ and girls’ roles, behaviors, and standards of morality. Although such attitudes may stop many children from asking questions, according to UN surveys of adolescent sexual behavior, it does not stop them experimenting: many young people are having sexual relationships, often from a very young age.[12] Many do so without essential information and without adequate access to contraception.[13]

Across the African Union, many governments have failed to implement comprehensive, scientifically accurate, age-appropriate sexuality and reproductive education.[14] This means that many girls and boys have limited understanding of changes in their bodies and adolescent sexual behavior, prevention of pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections, the menstrual cycle, basic reproduction, and sexual and gender-based violence. In Senegal, and Tanzania, for example, many girls interviewed by Human Rights Watch did not know they could become pregnant the first time they had sexual intercourse.[15]

Some countries continue to teach abstinence from sexual relationships before marriage.[16] Global scientific, sociological and human rights evidence shows that an abstinence-only curriculum leads to no visible change in adolescent sexual behavior.[17] A heavy focus on abstinence also isolates and humiliates many adolescents who have already had sex, and prevents them from obtaining the information and services that will protect them from abuse, unwanted pregnancy, or HIV and other sexually transmitted infections.[18]

Moreover, very few countries have adopted laws that clarify the age of consent to sexual activity.[19] Some countries still criminalize consensual sexual activity between adolescents, or sexual relationships outside marriage.[20] As part of their efforts on adolescent reproductive rights, UN agencies and human rights treaty monitoring bodies have called on governments to introduce an acceptable minimum legal age for sexual consent, balancing child protection and a child’s evolving capacities.[21] According to the Committee on the Rights of the Child, which provides authoritative commentary on the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, states should include a “legal presumption that adolescents are competent to seek and have access to preventive or time-sensitive sexual and reproductive health commodities and services.” They should also avoid criminalizing adolescents of similar ages for factually consensual and non-exploitative sexual activity.[22]

The majority of AU countries do not provide accessible adolescent-friendly, confidential sexual and reproductive health services. Moreover, most AU countries criminalize abortion in most circumstances, meaning girls with unplanned pregnancies must either carry those pregnancies to term against their wishes, or obtain clandestine—and often unsafe—abortions.[23] Of all the regions in the world, Africa has the highest number of deaths from unsafe abortion.[24]

Key Barriers to Girls’ Education

I am 16, I ran away from home to get married when I was 14 after I had sex with my boyfriend, who was 21. I was afraid my family would discover that I had had sex, so I went to live with my boyfriend as his wife. I was in grade seven at the time and stopped going to school. After about seven months my husband and his three brothers began to complain that I was not getting pregnant. He never beat me but always complained that I was barren. I used to do a lot of hard work washing clothes, cleaning and cooking for my husband and his relatives. After two years of marriage he sent me away saying I am barren, and my mother took me back. My wish is to go back to school but my mother cannot afford to send me back to school.

—Munesu C., 16, Zimbabwe, October 2015

Across the African continent, girls face unique challenges in education attainment due to structural and systematic gender inequalities. Despite government efforts, there remain significant gender disparities in educational opportunities and clear gender gaps in learning and skills achievement.[25]

The barriers to girls’ education are wide-ranging and interlinked, but few African governments have tackled the key factors that drive millions of girls out of school, including:

- High school fees combined with indirect costs of attending primary and secondary school[26];

- Unsafe school environments including sexual abuse, harassment and exploitation by teachers, school officials and classmates; stigma linked to pregnancy and marital status; corporal punishment by teachers and school officials, which sometimes amounts to inhuman and degrading treatment; and long distances to schools in rural areas that expose girls to sexual violence and other safety risks[27];

- Discrimination by teachers and school officials, and lack of accessibility for girls with disabilities[28];

- Poor infrastructure including lack of adequate water and toilets, and running water, to manage menstrual periods[29]; and

- Harmful gender norms and stereotypes that do not support education of girls and women, discrimination, and cultural practices such as child marriage.[30]

Pregnancy is both a barrier to girls’ continuing their education and, often a consequence of girls dropping out. Numerous studies have shown that the longer a girl stays in school, the less likely she is to be married as a child and or to become pregnant during her teenage years.[31]

II. Pregnant Girls and Adolescent Mothers’ Education: Human Rights Obligations of Governments

African governments are bound by international human rights law to provide free, compulsory primary education and to ensure that secondary education is available and accessible to all without discrimination.[32]The right to secondary education includes “the completion of basic education and consolidation of the foundations for life-long learning and human development.”[33]

Human Rights Watch has called on governments around the world t0 take immediate measures to ensure that secondary education is available and accessible to all free of charge. It is recognized that many governments in Africa and elsewhere face serious resource constraints that limit their ability to immediately realize important human rights goals such as free secondary education for all. Human Rights Watch nonetheless believes that it is important for governments to treat access to free secondary education as an urgent and immediate priority rather than as a goal to be realized progressively over time.

At the African regional level, the AU has adopted a legal framework that protects the rights of all girls to education. All but seven African countries have ratified the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, which obligates governments to take special measures to ensure equal access to education for girls, raise the minimum age of marriage to 18, and take all appropriate measures to ensure that girls who become pregnant before completing their education have the right to continue their education.[34]

The African Youth Charter–ratified by more than half of African governments– obligates governments to ensure girls and young women who become pregnant or married before completing their education have an opportunity to continue their education.[35] The African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights and the African Committee of Experts on the Rights and Welfare of the Child have called on states to put in place measures to retain all children in school, put in place measures to achieve equal access to education by girls and boys, and to encourage pregnant girls to attend or return to school. These bodies have jointly stated that, “it is compulsory… to facilitate the retention and re-entry of pregnant or married girls in schools… and to develop alternative education programmes… in circumstances where women are unable or unwilling to return to school following pregnancy or marriage.”[36]

The Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa, also known as the African women’s rights treaty, provides explicit obligations to guarantee the sexual and reproductive rights of girls.[37] This includes the right to access medical abortion in cases of sexual assault, rape, incest or where the pregnancy endangers the mother’s mental and physical health and life.[38]

III. Teenage Pregnancy and Education Exclusion

in the African Union

There was a [private] tuition teacher who was teaching me privately. I was sexually [abused] by the teacher until I found myself pregnant. After I discovered I was pregnant, I told the teacher and he disappeared. My dream was shattered then. I was expelled from school. I was expelled from home, too. I went to live with my friend until I gave birth. I was taking care of my baby on my own by doing small business. Until now.

—Imani, 22, Mwanza, Tanzania, January 2016

A growing number of African Union countries have adopted laws and policies that protect adolescent girls’ right to stay in school during pregnancy and motherhood. These countries can serve as a model for many other countries that lack adequate policies, and particularly persuade the minority of countries that have adopted or encouraged punitive and discriminatory measures against adolescent mothers to adopt human rights compliant policies. Although it is noteworthy that more governments are opting to keep adolescent mothers in school, their laws and policies are not always implemented fully, and monitoring of adolescent mothers’ re-entry to education remains weak overall.

Countries with Continuation or Re-entry Laws and Policies

Twenty-six AU countries have laws, policies or strategies in place to guarantee girls’ right to go back to school after pregnancy.[39]

Within this group of countries, six have laws that allow girls to continue their education.[40] However, the lack of policies that stipulate the process to be followed by schools in order to secure girls’ continuation after pregnancy often results in girls being expelled from school.[41]

|

Countries with national laws related to pregnant girls’ and mothers’ right to education |

|

|

Benin |

Democratic Republic of Congo |

|

Lesotho |

Mauritania |

|

Nigeria |

South Sudan |

Four countries have policies or strategies that provide “continuation:” they allow the pregnant girl to remain in school, and do not prescribe a mandatory absence after giving birth.[42]

|

Countries with policies or strategies that provide “continuation” |

|

|

Cape Verde |

Gabon |

|

Ivory Coast |

Rwanda |

Fifteen countries have conditional re-entry policies that require pregnant girls and young mothers to drop out of school but provide avenues to return, provided girls fulfill certain conditions.[43] Re-entry policies typically require that a student leaves school once she is found to be pregnant. In some cases, if the person responsible for the pregnancy is a student in the school he will also need to take leave of absence.[44] The girl may be readmitted – sometimes in a different school – after giving birth.[45] Policies and practice vary especially regarding the length of time the girl should be absent from school and the processes for withdrawal and re-entry.[46]

|

Countries with “re-entry” policies that set out conditions for adolescent mothers |

|

|

Botswana |

Burundi |

|

Cameroon |

Gambia |

|

Kenya |

Liberia |

|

Madagascar |

Malawi |

|

Mozambique |

Namibia |

|

Senegal |

South Africa |

|

Swaziland |

Zambia |

|

Zimbabwe |

|

Some conditions for re-entry are difficult for girls to meet.[47] In some cases, these are complicated or unclear, or include harmful directives such as mandatory pregnancy screening.[48] In Malawi, for example, girls are immediately suspended upon discovery of their pregnancy for one year but may be readmitted at the beginning of the next academic year following their suspension. A young mother who wishes to reapply for admission must send two requests: one to the Ministry of Education and one to the school she wishes to attend.[49] In Senegal, adolescent mothers must present a medical certificate showing they are healthy and fit to study in order to be re-admitted.[50]

Beyond their re-entry policies, some of these governments have addressed specific barriers to young mothers’ returning to school, for example:

- Removing primary and secondary school fees and indirect costs;

- Providing special accommodations for young mothers at school, for instance time for breast-feeding or allowing girls to take time off when their children are ill[51];

- Implementing flexible learning arrangements, such as giving girls the option to access morning or evening shifts[52];

- Providing social and financial support to adolescent mothers[53];

- Establishing nurseries or early childhood centers close to secondary schools[54]; and

- Providing school-based counselling services for pregnant girls and/or adolescent mothers.[55]

|

Senegal: Supporting the Inclusion of Young Mothers

In 2007, Senegal adopted a circular on “the management of marriage and pregnancies at school,” which orders schools to temporarily suspend girls from education until childbirth for “security” reasons. To go back to school, girls must show a medical certificate that shows they are ready to return to school. Girls can get these certificates when they visit local health clinics or hospitals. In practice, Human Rights Watch found that girls are allowed to stay in school until they are unable to attend, although some schools ask girls to drop out during the sixth or seventh month of pregnancy. Pregnant girls or young mothers can also take examinations. A principal in the southern town of Vélingara said that supporting pregnant girls is crucial to ensure they return once they are ready to resume their education: “There’s an awareness among staff that if they [young mothers] are late, or absent because of their babies, we understand [them]. [We also accommodate] pregnant girls who may fall asleep in class, or those who request some food because they are hungry.” Fatoumata, 17, lives in Sédhiou and attends a secondary school in the city. She became pregnant when she was 16 and was allowed to stay at the school. A month after giving birth, she continued going to school. Her grandmother took care of her baby daughter. “I didn’t want to have a baby,” Fatoumata told Human Rights Watch. “I’ve told all my friends that they do not try to have a baby… it causes many problems… But if you do have a baby, then you should go back to school after the birth. There’s no need to feel ashamed. Mistakes are human.” Fatoumata was not taught about sexual and reproductive health at school. “It would have been very useful to have information about contraceptive methods,” she said. Human Rights Watch found that in some Senegalese schools, teachers focus their discussions on abstinence and virginity prior to marriage. Some schools host school clubs to talk to students about contraceptive methods, and prevention of pregnancies, HIV and sexually transmitted diseases. Human Rights Watch found that in some clubs, girls are falsely told that contraceptives are bad for girls who are not married because they reduce their chances of getting pregnant or can lead to the fetus’s death during pregnancy. |

In many cases, poor dissemination at the school level and lack of awareness of these policies by teachers, communities, and girls themselves limit their effectiveness.[56] For example, education officials do not proactively follow-up on girls who left school due to pregnancy to initiate re-entry. Data is largely lacking on the number of girls who drop out due to pregnancy; teenage mothers that have been readmitted to school under the policies; the challenges they face after readmission; and, the performance of adolescent mothers once they are back at school.[57]

Some countries have moved from restrictive and even punitive policies to providing pathways for girls to continue.[58] In 2017, for example, Cape Verde reversed its expulsion policy, providing pregnant students with maternity leave, and committed to guarantee reasonable accommodations in schools with young mothers.[59]

At time of writing, in Ghana and Uganda, government and civil society actors were discussing school re-entry policies or guidelines for young mothers’ education.[60]

Countries affected by armed conflict typically have high pregnancy rates due, in part, to widespread sexual violence committed by members of national armed forces and armed groups, and high levels of poverty that facilitates sexual exploitation. These countries especially need strong re-entry policies. Crisis situations increase gender inequality and gender-based discrimination, which is already present in many countries undergoing conflict. Some survivors of sexual violence never return to school because of stigma and humiliation, and those who do return to school often lack support to continue their education.[61] The Democratic Republic of Congo and South Sudan, for example, have laws that protect young mothers’ right to go back to school.[62] In contrast, Human Rights Watch found that the Central African Republic lacks a targeted law or policy.[63]

Human Rights Watch found that education needs-analysis and responses in humanitarian crises seldom include adolescent girls with children.[64] The failure to provide for the education needs of adolescent mothers, including those who are survivors of rape, in humanitarian settings not only limits access to education, but also exposes already vulnerable children to more violence, hardship, and poverty.

Countries that Exclude Adolescent Mothers

A minority of AU governments have continued to explicitly exclude pregnant girls from school. Senior government representatives in countries such as Equatorial Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Tanzania have publicly declared that pregnant students are to be expelled from public school.[65]

In these countries, politicians have frequently insisted on punitive measures imposed on girls they accuse of being “moral failures”.[66] In Tanzania, government officials and police have gone so far as arresting pregnant girls and harassing their families to force them to confess who had impregnated them.[67] Many of the girls Human Rights Watch interviewed who dropped out of school or were expelled due to pregnancy or marriage expressed regret at not being able to continue their education.[68]

Although Togo has declared to United Nations bodies that it no longer abides by a regulation that forbids pregnant girls from going to education facilities, it has not officially abrogated it or replaced it with a positive continuation or re-entry policy.[69]

|

Tanzania: Discriminatory Policies Against Pregnant Girls and Young Mothers The United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, the African Committee on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, and the African Commission’s Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Women in Africa, among others, have called on the government of Tanzania to cease its discriminatory ban on pregnant girls. Human rights experts have called on the government to urgently ensure pregnant girls and adolescent mothers can resume education in public schools.[70] Prior to President John Magufuli’s 2017 public ban on pregnant girls and young mothers in schools, senior government education officials contended that pregnant girls do not belong in school and may exert negative influence on other girls, “normalizing” pregnancy in school.[71] The expulsion of pregnant girls from schools is permitted under Tanzania’s education regulations, which state that “the expulsion of a pupil from school may be ordered where … a pupil has … committed an offence against morality” or “entered into wedlock.” [72] The policy does not explain what offences against morality are, but school officials often interpret pregnancy as such an offense. Secondary school officials routinely subject girls to forced pregnancy testing as a disciplinary measure to expel pregnant students from schools. In 2018, the government has been preparing new guidelines that will outline entry into an existing parallel public basic education system for young mothers, similar to an existing track for out-of-school children. Human Rights Watch found that this system is deficient, comes at a high cost for students, and does not equip students with the same skills or provide similar accreditation. Students pursuing this route have to pay fees that can amount to about 500,000 Tanzanian shillings (TZS) (US$220) annually, whereas students in public schools do not pay tuition or indirect costs. Access to good vocational training is only provided in a handful of colleges spread across the country. Moreover, adolescents who leave secondary school prematurely lack the accreditation and studies needed to pursue an official vocational education and skills training degree.[73] |

Countries Lacking Clear Policies

Twenty-four countries lack a re-entry policy or law to protect pregnant girls’ right to education, including at least six countries that criminalize sex outside marriage. [74] This often leads to irregular enforcement of compulsory education at the school level, where school officials can decide what happens with a pregnant girl’s education. In Burkina Faso, for example, government officials have adopted a strategy to prevent teenage pregnancies, but school officials often ban pregnant girls from school because of strong social norms, as well as stigma attached to having children outside wedlock.[75] In Angola, for example, pregnant girls are asked to shift to night schools.[76]

|

Countries Lacking Clear Policies or Legislation |

||

|

Angola |

Burkina Faso |

Central African Republic |

|

Chad |

Comoros |

Djibouti |

|

Eritrea |

Ethiopia |

Ghana |

|

Guinea |

Guinea-Bissau |

Mauritius |

|

Niger |

Republic of Congo |

São Tomé e Príncipe |

|

Seychelles |

Somalia |

Uganda |

Countries that Criminalize Sex Outside Marriage

Human Rights Watch found that countries in northern Africa generally lack policies related to the treatment of teenage pregnancies in school, but at the same time impose heavy punishments on girls and women who are reported to have had sexual relationships outside wedlock.[77] Countries such as Morocco and Sudan, for example, apply “morality laws” that allow them to prosecute adolescent girls or young women and charge them with adultery, indecency or extra-marital sex.[78] Girls and young women with children, who are often perceived to bring dishonor to their communities, are exposed to public ridicule, isolation, and prison sentences, and would not be expected to stay in school.[79]

|

Leave No Adolescent Girl Behind? |

|||||

|

Countries with expulsion policies or decrees |

Countries with conditional “re-entry” policies |

Countries with policies or strategies that provide “continuation” |

Countries with laws that protect pregnant girls’ right to stay in school or resume education, but lack a policy |

Countries with laws or practices that criminalize girls and young women who become pregnant outside marriage |

Countries with no laws or policies related to retention of pregnant girls or adolescent mothers in schools |

|

Equatorial Guinea |

Botswana |

Cape Verde |

Benin |

Algeria |

Angola |

|

Sierra Leone |

Burundi |

Gabon |

Democratic Republic of Congo |

Egypt |

Burkina Faso |

|

Tanzania |

Cameroon |

Ivory Coast |

Lesotho |

Libya |

Central African Republic |

|

Togo |

Gambia |

Rwanda |

Mauritania |

Mauritania |

Chad |

|

Kenya |

Nigeria |

Morocco/Western Sahara |

Comoros |

||

|

Liberia |

South Sudan |

Sudan |

Djibouti |

||

|

Madagascar |

Tunisia |

Eritrea |

|||

|

Malawi |

Ethiopia |

||||

|

Mali |

Ghana |

||||

|

Mozambique |

Guinea |

||||

|

Namibia |

Guinea-Bissau |

||||

|

Senegal |

Mauritius |

||||

|

South Africa |

Niger |

||||

|

Swaziland |

Republic of Congo |

||||

|

Zambia |

São Tomé and Príncipe |

||||

|

Zimbabwe |

Seychelles |

||||

|

Somalia |

|||||

|

Uganda |

|||||

IV. Opening School Doors to All Adolescent Girls

Pregnancy and child bearing are significant life changing events, more so for young girls. Going through these experiences while still at school – often stigmatized or rejected, with little to no support from the family or school, condemned by government officials, facing economic hardship and sometimes abuse and violence – can present serious challenges for pregnant girls and adolescent mothers to continue with their education.

However, instead of labeling pregnant girls and adolescent mothers as “moral” failures, punishing and excluding them from school, African governments have obligations under international human rights law to encourage and support the education and academic progress of these girls without discrimination.

Overall, a comprehensive approach is needed to reduce early and unplanned teenage pregnancies and support young mothers to continue with education. Good practice from across the continent shows that the education sector can play an important role in addressing teenage pregnancies, including by addressing some of its underlying causes and responding to the educational, health and social impacts and needs of pregnant and adolescent mothers.

African Union countries adhering to good policies and practice have at a minimum focused on the following measures: supporting girls to stay in school by removing primary and secondary school fees to ensure all students can equally access school; providing financial support for at-risk and highly vulnerable girls; ensuring schools are safe for students by ensuring schools have adequate child protection mechanisms; providing adolescents with access to sexual and reproductive health services, including comprehensive sexuality education at school and in the community; and ensuring access to a range of contraceptive methods, and safe and legal abortion.[80]

Schools should ensure the inclusion of all students and take all necessary measures to protect children from sexual abuse, exploitation, or harassment. Schools should also play a key role in providing students with the information and tools to understand changes in adolescence, sexuality, and reproduction, and provide information that enables them to make informed decisions, without the pressure, stereotypes, or myths shared by their friends or communities.

Governments should adopt mandatory national school curricula that includes sexual and reproductive health and rights, responsible sexual behavior, forming healthy relationships, prevention of early pregnancy and marriages, prevention of sexually transmitted infections, gender equality, and awareness and prevention of sexual exploitation and sexual and gender-based violence.[81] Evidence-based technical guidance shows that children should be introduced to age-appropriate content on sexuality and reproductive health in primary school, prior to puberty.[82]

Acknowledgments

This report was written by Elin Martínez, researcher in the Children’s Rights Division at Human Rights Watch, and Agnes Odhiambo, senior researcher in the Women’s Rights Division. Research for this report was conducted by Elin Martínez, with assistance from Allison Cowie, Aurélie Edjidjimo Mabua and Elena Bagnera, Children’s Rights interns, Ochieng Angayo, research assistant, and Leslie Estrada, Children’s Rights Division associate.

The report was edited by Zama Neff, Children’s Rights Division executive director. James Ross, Legal and Policy director, and Babatunde Olugboji, deputy program director, provided legal and program reviews. Margaret Wurth, researcher in the Women’s Rights and Children’s Rights Divisions; Maria Burnett, Africa associate director, Corinne Dufka, West Africa associate director; and Mausi Segun, Africa Division executive director, provided expert reviews. The report also benefited from reviews by researchers in the Africa, and Middle East and North Africa divisions. Dr. Chi-Chi Undie, of the Population Council, provided external review. Peter Huvos provided translation assistance. Production assistance was provided by Leslie Estrada, Children’s Rights Division associate, and Fitzroy Hepkins, administrative manager.

We would like to thank experts at national and international nongovernmental organizations, education ministries and United Nations agencies who assisted us in conducting the research for this report, and shared data and other information with us. These experts and representatives include: Van Daniel of Pairs Educateurs et Promoteurs sans Frontieres in Cameroon, Nicolas Effimbra of the Ministry of Education of Ivory Coast, Najlaa Elkhalifa, Desiré Essossinam Adjoke of Plan International Togo, Bernard Makachia of Education for Better Living, Sabrina Mahtani of Amnesty International, Trine Petersen of UNICEF Lesotho, Ndiaye Khadidiatou Sow of the Ministry of National Education of Senegal, and Boaz Waruku of the African Network Campaign on Education for All. We would also like to thank Dr. Chi-Chi Undie of Population Council for providing peer review, and Françoise Kpeglo Moudouthe, of Girls not Brides, for strategic advice.