Summary

We spent a week there. [The anti-balaka] raped us every day…. We had become their “wives.” It was us who prepared the food…. At any moment, they would want to sleep with you and, if you resisted, they threatened to kill you….

I said I am the daughter of a Christian. [Their leader] said, “No, you are the daughter of a Muslim.” I said no. He said, “Those are your brothers who have killed our brothers. It’s you who are going to pay.” … I was 12 years old at the time.

[After we escaped,] when I arrived [in Boda] there was no hospital, nothing. Later, when [an aid organization] got here they did a urine test, blood test. At the hospital, I didn’t explain what had happened. I couldn’t explain. I said I was taken by anti-balaka, but not that I was raped.

–Zeinaba, 15, Boda, April 2016

I was with my husband in the house. The Seleka came…. They pushed my husband to the ground and two pointed their guns at him. Then four of them rushed at me and pushed me to the ground. Each of the four then raped me. My husband was in the room, but they would not let him move.

I have thought about what these men did and justice for myself. I want these men brought to justice and put in prison.

–Marie, 30, Bambari, January 2016

Since late 2012, the Central African Republic has been wracked by bloody armed conflict in which civilians have paid the price. Armed groups have brazenly violated the laws of war with impunity, attacking civilians and civilian infrastructure, and leaving trails of death, displacement, and destitution in what was already one of the world’s poorest countries.

During nearly five years of conflict, armed groups have also brutalized women and girls. The predominantly Muslim Seleka and the largely Christian and animist militia known as “anti-balaka,” two main parties to the conflict, have both committed sexual slavery and rape across the country. Human Rights Watch documented fighters using sexual violence to punish women and girls, frequently along sectarian lines, as recently as May 2017.

Armed groups have not simply committed sexual violence as a byproduct of fighting, but, in many cases, used it as a tactic of war. Commanders have consistently tolerated sexual violence by their forces and, in some cases, they appear to have ordered it or to have committed it themselves.

Though it continues to haunt women and girls physically, emotionally, socially, and economically, sexual violence—like other conflict-related crimes—has thus far gone unpunished. To date, no member of an armed group has been arrested or tried for committing sexual slavery or rape.

Following years of disenfranchisement and neglect, rebel groups consisting primarily of Muslim fighters formed in the northeast under the banner of the Seleka in late 2012 and launched attacks that killed scores of civilians, burned and pillaged homes, and displaced thousands. In response, Christian and animist militia known as anti-balaka emerged in mid-2013 and began to organize counterattacks. Associating all Muslims with the Seleka, the anti-balaka carried out large-scale assaults on Muslim civilians in Bangui and western parts of the country. As the Seleka and the anti-balaka engaged in reprisal attacks, at times both sides targeted civilians along sectarian lines. By mid-2014, after having been ousted from Bangui by African Union and French forces, the Seleka split into several factions. These Seleka groups have at times allied and fought each other, sometimes making alliances with anti-balaka groups.

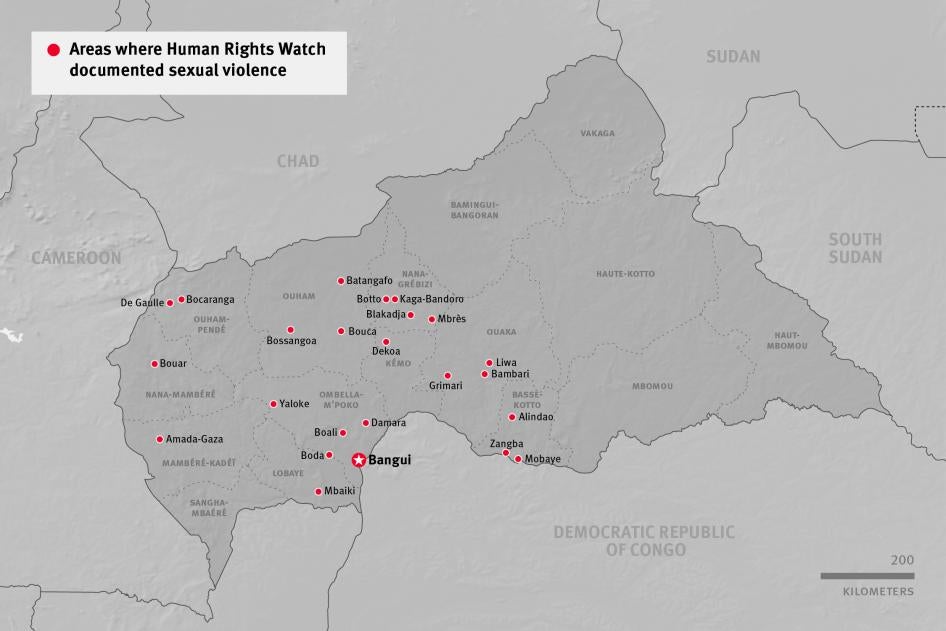

Based primarily on interviews with 296 survivors, this report documents pervasive sexual violence against women and girls perpetrated by Seleka and anti-balaka fighters from early 2013 to mid-2017. It presents detailed cases of rape, sexual slavery, physical assault, and kidnapping of women and girls between the ages of 10 and 75, primarily in the capital, Bangui, and in and around the towns of Alindao, Bambari, Boda, Kaga-Bandoro, and Mbrès.

The report presents the most comprehensive documentation to date of widespread sexual violence against women and girls by fighters affiliated with the anti-balaka and the various Seleka factions. It details how these armed groups have subjected women and girls to violent and sometimes repeated rape resulting in long-term consequences, including illness and injury, unwanted pregnancy, stigma and abandonment, and loss of livelihoods or access to education. The report also exposes the immense barriers that impede survivors from accessing even basic medical and psychosocial care following rape.

The United Nations peacekeeping mission, authorized to have 12,870 armed forces in the country, has a mandate to protect civilians, including from sexual violence, but it has struggled to prevent armed groups from committing crimes against women and girls and to respond adequately in cases of sexual violence.

The government retains primary responsibility for protecting women and girls from sexual violence but, with fighting having decimated the country’s institutions, including courts and detention facilities, authorities lack capacity to prevent, investigate, and prosecute sexual violence or to ensure availability of critical services for survivors. Still, government and other service providers have not always taken all possible measures to provide necessary assistance to survivors who report the crime.

In a country where the justice system is largely dysfunctional—with only a handful of operational courts, few lawyers and judges, and minimal capacity to investigate sexual violence or detain perpetrators—survivors have little or no opportunity to seek redress. Though the Central African Penal Code punishes rape and sexual assault as criminal offenses, no member of an armed group has been tried for rape during the conflict. Only 11 of the 296 sexual violence survivors interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they attempted to file a criminal complaint. They reported powerful deterrents to seeking justice, including death threats and physical attacks for daring to come forward, and feeling intimidated and powerless when seeing their known attackers move freely around their villages and towns.

An ongoing International Criminal Court (ICC) investigation into crimes committed in the country since August 2012 could bring a measure of justice for crimes in the conflict. But the ICC, which only investigates those responsible for the gravest international crimes, can prosecute only a small number of individuals at high levels of power.

The recently-established Special Criminal Court—a novel, hybrid domestic and international court embedded within the national justice system—offers hope for greater justice for the war crimes and possible crimes against humanity that have plagued the Central African Republic since 2003. Its success, however, depends on sustained political and financial backing from the government and the country’s international partners, as well as effective procedures to protect witnesses, victims, and court personnel.

This report offers recommendations to mitigate risks for women and girls, and to ensure that survivors of sexual violence access essential medical care, psychosocial support, and justice. Curbing Seleka and anti-balaka abuses and holding perpetrators to account requires a long-term, multi-pronged approach, but the government, the United Nations, and international donors can take immediate steps to strengthen protection for civilians at risk of sexual violence and to improve services for sexual violence survivors.

Rape as a Tactic of War

Commanders from the two main parties to the conflict have tolerated sexual violence by their forces; in some cases, they appear to have ordered and committed it. At times, rape formed an integral part of armed assaults and was used as a weapon of war.

Members of armed groups committed rape during attacks on towns and villages, sometimes during door-to-door searches for men and boys. Seleka and anti-balaka fighters also attacked women and girls as they carried out essential tasks such as going to markets, cultivating or harvesting crops, and going to and from school or work. Perpetrators often directed attacks at women and girls due to their presumed religious affiliation, with the predominantly Muslim Seleka fighters targeting women and girls from Christian communities, and the anti-balaka targeting Muslim women and girls.

In many cases, survivors said their attackers used sexual violence as a form of retribution for perceived support of those on the other side of the sectarian divide. Seleka fighters taunted women and girls by calling them “anti-balaka wives” and anti-balaka fighters accused their victims of supporting Muslims. In some instances, armed groups used sexual violence as punishment for the alleged alliances of survivors’ male relatives. In one instance, a survivor said fighters raped her husband, forcing her to watch, before killing him and raping her.

In most cases, survivors said that multiple perpetrators raped them—sometimes 10 men or more during a single incident. The rapes of these women and girls, which resulted in injuries ranging from broken bones and smashed teeth to internal injuries and head trauma, constitute torture. Torture was exacerbated in some cases by additional violence, including rape with a grenade and a broken bottle. Perpetrators also tortured women and girls by whipping them, tying them up for prolonged periods, burning them, and threatening them with death. Sexual slavery survivors were held captive for up to 18 months, repeatedly raped—some taken as fighters’ “wives”—and forced to cook, clean, and collect food or water.

Members of armed groups aggravated the humiliation by raping some women and girls in front of their husbands, children, and other family members. Survivors told Human Rights Watch they witnessed fighters rape their daughters, mothers, or other female family members or kill and mutilate their husbands and other relatives.

In interviews with 257 women and 39 girls (ages 17 and under) Human Rights Watch documented 305 cases of sexual violence by members of armed groups. At least 13 of the women survivors were girls at the time of the violence. Some survivors experienced sexual violence multiple times, on separate occasions. In some cases of sexual slavery—wherein fighters committed sexual violence and exerted ownership over victims—women or girls experienced multiple rapes over a period of days, weeks, or months. In 21 additional cases, 17 women and 4 girls said they experienced violence by armed groups—including abduction, beatings, and other physical abuse—but did not discuss sexual violence. Two of these women told Human Rights Watch about other incidents of sexual violence they experienced by members of armed groups.

The number of incidents reflects those documented by Human Rights Watch during research for this report and does not indicate an attempt to provide a comprehensive record of incidents of sexual violence committed by armed groups in the Central African Republic at any period. As a result of stigma, under-reporting by survivors, and time constraints and security-related restrictions on research, the cases documented in this report likely represent a small proportion of all sexual violence incidents perpetrated by armed groups in the country during the period covered. The United Nations, for example, recorded over 2,500 cases of sexual violence in 2014 alone.

Some survivors said they could identify the men who abused them or commanded the fighters committing the abuse. This report names six individuals in leadership positions of armed groups whom three or more survivors identified as having committed sexual violence or having had fighters under their command and control who committed such crimes.

Human Rights Watch also heard credible reports of armed groups committing sexual violence against men and boys, but research conducted for this report focuses on violence against women and girls.

The report does not address sexual exploitation and abuse, including rape, committed by members of the United Nations peacekeeping force, some cases of which Human Rights Watch has previously documented, or by members of non-UN peacekeeping forces operating in the Central African Republic.

Care Denied

Sexual violence has been life-altering for most of the women and girls Human Rights Watch interviewed. Only 145 of the 296 sexual violence survivors had accessed any post-rape medical care due to a range of obstacles, such as a lack of medical facilities, cost of travel to such facilities, and fear of stigma and rejection. Of these, only 83 survivors confirmed that they had disclosed the sexual violence to health care providers, thus allowing for comprehensive post-rape health care. In only 66 cases had survivors received any psychosocial support.

Human Rights Watch interviewed women and girls who face incapacitating physical injury and illness. Others became pregnant from rape, sometimes bearing children that present an emotional and financial burden. Mental health consequences are no less dire. Women and girls described symptoms consistent with post-traumatic stress and depression, including suicidal thoughts, fear and anxiety, sleeplessness, and an inability to complete daily tasks. Unable to continue work or other activities for sustenance, many said they are struggling to resume their lives and support themselves and their families. Girls sometimes dropped out of school due to fear of repeated violence, risk of stigma, or continued insecurity or displacement.

Fear of stigma and rejection often keeps women and girls from disclosing rape, even to close friends and family members, and from seeking help. The risk is all too real: women and girls told Human Rights Watch about husbands or partners abandoning them, family members blaming them, and community members taunting them after rape.

Stigma is one of many barriers to accessing critical health and psychosocial services. With a substantial proportion of health facilities destroyed by conflict and insecurity restricting access to others, service availability remains limited, especially outside major towns. Where services are available, they often do not offer comprehensive, confidential post-rape care or appropriate referrals for medical treatment or psychosocial support.

The government has committed to providing free health services for sexual violence survivors, but some women and girls said that service providers required payment for tests or treatment. Others said they did not seek health care because they believed it would cost money they did not have, or because they could not pay for transport to services.

Crimes Unpunished

Most of the cases documented in this report are not only crimes under Central African law, but constitute war crimes. In some cases, the conduct of both the Seleka and anti-balaka may constitute crimes against humanity. Despite this, not a single member of either armed group is known to have been punished for committing sexual violence. Perpetrators continue to hold positions of power in armed groups and exercise control over civilian populations. Several survivors said they saw their tormenters walking free after having committed rape.

The Central African government, donor governments, and the United Nations have publicly committed to support the fight against impunity for war crimes, but accountability remains a fragile hope, especially for conflict-related sexual violence. Nearly five years of conflict have left an already-faltering national justice system with few functioning courts or jails and limited capacity among judges, attorneys, and the security sector. In many areas where armed groups maintain control, national police and gendarmes are entirely absent.

Survivors expressed little faith in the justice system and often believed that their attackers would never be investigated, arrested, or prosecuted, and historic impunity for sexual violence provides little evidence otherwise. Only 11 survivors interviewed by Human Rights Watch said they had attempted to initiate a criminal investigation. Those who informed authorities faced mistreatment, including victim-blaming, failure to investigate, and even demands to present their own perpetrators for arrest. Family pressure, economic strain, and fear of reprisals further deter survivors from seeking justice. In at least three cases, survivors or their family members who directly confronted members of the armed group responsible for sexual violence were killed, beaten, or threatened with death. Witness and victim protection—currently non-existent in the national justice system—will be essential to facilitating accountability. Other obstacles to investigation and prosecution include difficulty identifying perpetrators and inconsistent provision of medical reports attesting to signs of rape.

The government has no national strategy to prevent or address sexual violence, though some consultations to develop one had taken place at time of writing. Under national, regional and international law, the Central African Republic has obligations to prevent and respond to sexual violence, and to hold perpetrators accountable. Even with its limited capacity, the government can and should take measures to strengthen protections for women and girls, and improve access to services and justice for sexual violence survivors. Donor governments and international agencies providing aid to the country also play an essential role in supporting efforts to enhance protection from and response to sexual violence.

Without significant action to prevent sexual violence by armed groups, assist survivors, and end impunity for perpetrators, women and girls in the Central African Republic will continue to suffer not only at the hands of their attackers, but also from systemic failures to provide protection, support, and justice.

Key Recommendations

Full recommendations can be found at the end of this report.

To prevent sexual violence against women and girls and to assist those who have suffered the abuse, Human Rights Watch recommends:

- That Seleka and anti-balaka leadership immediately cease attacks on civilians and issue clear, public orders to their respective forces to stop all sexual violence—including harassment and intimidation—in areas under their control.

- That the government of the Central African Republic:

- Issue a public and unambiguous message to Seleka and anti-balaka leadership that it will show zero tolerance for sexual violence and make every effort to bring all perpetrators of sexual violence to account.

- Provide free and confidential health and psychosocial services to survivors of sexual violence, including comprehensive post-rape medical care, with support from the United Nations agencies, donor governments, and nongovernmental organizations.

- Train police, gendarmes, prosecutors, and judges in how to respond to, investigate, and prosecute cases of sexual and gender-based violence. Provide ongoing support for the Mixed Unit for Rapid Intervention and Suppression of Sexual Violence against Women and Children (Unité Mixte d’Intervention Rapide et de Répression des Violences Sexuelles Faites aux Femmes et aux Enfants, UMIRR) to investigate sexual violence in accordance with international best practice standards. This includes recruiting and hiring female personnel, appointing and training focal points in all provinces, and working towards replication of the Mixed Unit at the provincial level.

- In cooperation with UN agencies and the UN mission, urgently develop and implement a national strategy to combat and respond to sexual violence, including conflict-related sexual violence.

- Develop and implement, in collaboration with the United Nations mission (MINUSCA), a strategy for civilian protection, including specific measures to protect women and girls and to mitigate the risk of sexual violence.

- In conjunction with the UN mission, expedite the operationalization of the Special Criminal Court and give the court full political support to fulfill its mandate, while respecting its independence.

- That the UN Mission to the Central African Republic:

- Assist authorities to identify, arrest, and prosecute perpetrators of crimes of sexual violence committed by armed groups as per the mission’s mandate.

- Bolster training and funding to police and other rule of law institutions, including prosecutors, judges, and those deployed to the Special Criminal Court (SCC) and UMIRR, on investigation and prosecution of sexual violence. Prioritize inclusion of female personnel in teams working on such cases.

- Incorporate witness and victim protection into support for the SCC and other judicial institutions, particularly for sensitive cases such as those involving sexual violence, in which witnesses or victims face risk of stigma, threats, injury, or death.

- That the UN Security Council:

- Impose targeted sanctions against Seleka and anti-balaka commanders responsible for committing, ordering, or tolerating sexual violence.

- That foreign donor governments:

- Provide additional resources and technical support for essential medical, psychosocial, and legal services for survivors of sexual violence.

- Expand support for efforts to re-establish the national judicial system and to train police, prosecutors, and judges in investigation and prosecution of sexual and gender-based violence.

- Give sustained political and financial support to the Special Criminal Court.

Methodology

This report is based on research conducted in the Central African Republic between July 2015 and August 2017. Researchers from Human Rights Watch interviewed survivors of violence, service providers, United Nations personnel, government officials and representatives of armed groups in Bangui in December 2015, January 2016, April and May 2016, and August 2017. Human Rights Watch also conducted interviews in the following locations: Bambari, in the Ouaka province (January 2016), Boda, in the Lobaye province (April 2016), Kaga-Bandoro, in the Nana-Grébizi province (May 2016), and Bocaranga, in the Ouham-Pendé province (November 2016). The report also draws from research Human Rights Watch conducted in Yaloké, in the Ombella-M’poko province, and in Kaga-Bandoro in April 2015. Human Rights Watch researchers conducted additional interviews with service providers and with government and UN representatives in Bangui in July 2015, June 2016, October 2016, and April 2017. For security reasons, representatives of government, UN agencies, and non-governmental organizations have not been named in this report.

Human Rights Watch makes every effort to abide by best practice standards for ethical research and documentation of sexual violence. In all but nine cases, survivors were offered the option to speak with a female researcher and female interpreter. Researchers conducted interviews in French with interpretation from Sango. In one case, a community member known to Human Rights Watch interpreted from Peuhl (Fulani) to Sango, which an interpreter working with Human Rights Watch then translated to French.

For reasons of security and privacy, all survivors are identified by pseudonyms. Human Rights Watch took measures to access and meet with survivors discreetly in confidential settings, keep identifying details confidential, and use interview techniques designed to minimize the risk of re-traumatization. Human Rights Watch preceded all interviews with a detailed informed consent process to ensure that survivors understood the nature and purpose of the interview and could choose whether to speak with researchers. Human Rights Watch informed survivors that they could stop or pause the interview at any time and could decline to answer questions or discuss particular topics. In cases where survivors said they were experiencing, or they appeared to be experiencing, significant distress, researchers sometimes limited questions about the incident of sexual violence or concluded the interview early. Some women and girls did not discuss experiences of sexual violence. Among these people, some may have experienced sexual violence but elected not to discuss it.

In cases of children who experienced sexual violence, especially for those aged 10 to 14, Human Rights Watch researchers took special care to avoid re-traumatization and did not ask survivors to describe incidents of sexual violence in detail. In some cases, researchers interviewed a survivor’s parent or other family member with knowledge of the incident instead of or in addition to the survivor. In the case of a woman with an intellectual disability, the researcher interviewed the survivor individually and then with her mother after obtaining the survivor’s consent.

Human Rights Watch did not pay for interviews, but did cover transportation costs to and from interview locations as needed. Researchers also arranged referrals to medical, psychosocial, and legal services for survivors where possible and with their informed consent.

In some cases, survivors had difficulty specifying the date of an assault. This was likely due to factors including low literacy, insignificance of calendar dates to daily life, and/or trauma resulting from the incident. In these cases, Human Rights Watch sought to establish the timing of incidents through other details provided by the interviewee and members of the community, as well as information about the activity of armed groups in the area. Because some interviewees could not provide their exact age or the date of the attack, in three cases Human Rights Watch could not determine with certainty whether the survivor was a child (under 18 years old) or an adult when the violence occurred.

Terminology

In this report, “child” refers to anyone under the age of 18. “Girl” refers to a female child.

Human Rights Watch uses the World Health Organization’s (WHO) definition of sexual violence as “[a]ny sexual act, attempt to obtain a sexual act, unwanted sexual comments or advances, or acts to traffic or otherwise directed against a person’s sexuality using coercion, by any person regardless of their relationship to the victim, in any setting.”[1]

The WHO defines rape as “the physically forced or otherwise coerced penetration of the vulva or anus with a penis, other body part or object.”[2] International bodies have clarified that determining whether an act amounts to rape is not dependent on use of physical force but rather on lack of consent of the victim and coercive circumstances, whether or not such circumstances include physical violence or threats of physical violence.[3] Human Rights Watch abides by the WHO definition of rape, with the understanding that “physically forced or otherwise coerced” circumstances include a lack of consent on the part of the victim or any form of coercion or threat.

Human Rights Watch refers to elements of the definition of sexual slavery elucidated by the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court: “The perpetrator exercised any or all of the powers attaching to the right of ownership over one or more persons, such as by purchasing, selling, lending or bartering such a person or persons, or by imposing on them a similar deprivation of liberty” and “the perpetrator caused such person or persons to engage in one or more acts of a sexual nature.”[4]

I. Background: Violence in the Central African Republic

The current conflict in the Central African Republic began in late 2012 when three rebel groups from the northeast, angered by years of neglect and ma"ltr"eatment by the government of then-President François Bozizé, emerged under the banner of the Seleka (“alliance” in the Sango language)[5]: the Convention of Patriots for Justice and Peace (Convention des Patriotes pour la Justice et la Paix, CPJP), the Patriotic Convention for the Salvation of Kodro (Convention Patriotique de Salut du Kodro, CPSK), and the Union of Democratic Forces for Unity (Union des Forces Démocratiques pour le Rassemblement, UFDR).[6] Many Seleka fighters were mercenaries from Chad and Sudan. While the Seleka did not profess a religious affiliation, their fighters were overwhelmingly Muslim.

Beginning in the northeast and moving towards the capital, Bangui, the Seleka launched attacks in late 2012 and 2013 during which they killed scores of civilians, burned and pillaged homes, and left over 850,000 people displaced.[7]

In March 2013, the Seleka seized control of Bangui, ousting President Bozizé and his government. Forces attacked and pillaged entire neighborhoods, killing and raping civilians.[8] Seleka leaders denied that their fighters had targeted civilians, despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary.[9]

In response to the widespread killings and destruction, local self-defense groups called “anti-balaka” (“anti-bullet”) began to emerge. While some anti-balaka groups are affiliated with or coordinated by former members of the national army or Bozizé’s presidential guard, most are relatively autonomous, operating in specific regions with loose ties to a central command.

The anti-balaka quickly demonstrated an anti-Muslim bias, equating all Muslims with Seleka sympathizers. By August 2013, the anti-balaka began launching attacks against the Seleka in the center of the country, targeting both Seleka fighters and Muslim civilians, including women, children, and the elderly.[10]

In September 2013, interim president Michel Djotodia, who had suspended the constitution and installed himself in power, announced that the government had dissolved the Seleka, but its fighters continued to operate around the country, with civilians bearing the brunt of the violence.

The Seleka splintered in 2014, eventually splitting into multiple groups including the Union for Peace (l'Union pour la Paix en Centrafrique, UPC), the Popular Front for the Renaissance of Central Africa (Front Populaire pour la Renaissance de la Centrafrique, FPRC), and the Central African Patriotic Movement (Mouvement Patriotique pour la Centrafrique, MPC).

Throughout 2013 and 2014, the Seleka and anti-balaka engaged in reprisal attacks, with both sides at times targeting civilians along sectarian lines.[11] In early 2014, due to anti-balaka attacks, as well as pressure from international peacekeeping forces based in the country (see below), the Seleka consolidated its operations in the country’s center and east, where they established strongholds and continued to abuse local communities.

Anti-balaka forces also committed serious abuses, including mass killings, against Muslims fleeing the southwest.[12] They continued to threaten Muslims living in UN-protected enclaves in the west while fighting the Seleka in the center of the country.

In addition, the Peuhl (or Fulani), a Muslim nomadic or semi-nomadic people, have aligned themselves with the Seleka and at times fought with Seleka forces. Anti-balaka have targeted Peuhl civilians because of this alliance or because they are Muslim.[13] Some Peuhl joined the Seleka and committed abuses, including the deliberate killing of civilians and burning of villages.[14]

Michel Djotodia stepped down as interim president on January 14, 2014, but intense fighting continued. Multiple efforts at national and international peace deals, including three major peace agreements in 2014 and 2015, failed to end the fighting.[15]

A transitional government was formed in January 2014, headed by Bangui’s former mayor, Catherine Samba-Panza, with a key goal of paving the way for elections. Presidential and parliamentary elections finally took place in early 2016, and Faustin-Archange Touadéra, who had served as prime minister from 2008 to 2013, won the presidency.[16] The peaceful transfer of power offered hope for peace but the conflict’s underlying causes—a security vacuum, impunity for perpetrators of abuse, failed disarmament and reintegration efforts, and lack of meaningful reconciliation between warring groups—remained unaddressed. The struggle for control of resources exacerbated the crisis.

Eight anti-balaka leaders campaigned for parliamentary seats in the January 2016 elections. Three were elected, including Alfred Yékatom, alias “Rombhot,” an anti-balaka leader who has been identified as responsible for abuses against civilians, including sexual violence, and is a commander on the United Nations sanctions list.[17]

In 2016, armed groups continued to perpetrate violence, including against civilians, especially in the central regions of Ouaka, Mbomou, and Haute-Kotto.[18] The Seleka factions attempted to reunify in August 2016, but the alliance was short-lived.[19] Fighting among Seleka factions in November 2016 intensified as Seleka factions allied with anti-balaka forces in Ouaka province in December 2016.[20] In 2017, fighting spread southeast to Haute-Kotto and Mbomou provinces, including in the key towns of Bria, Bangassou, and Zemio.

On June 19, the government and 13 of the 14 active armed groups signed a peace deal mediated by the Community of Sant'Egidio in Rome—an association close to the Vatican that promotes inter-faith dialogue—that includes a ceasefire and political representation for armed groups. The accord acknowledges the work of the Special Criminal Court and the International Criminal Court and includes a truth and reconciliation commission.[21] One day after the deal was signed, up to 100 people were reportedly killed in Bria in fighting between anti-balaka fighters and the FPRC.[22]

United Nations peacekeeping forces have struggled to protect civilians.[23] Fighting between various Seleka groups and anti-balaka remains a serious threat to civilians in the center of the country. The Seleka operate in the center and east, resulting in a de facto partitioning of the country. The UPC were based in Bambari, in Ouaka province, until early 2017 when the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in the Central African Republic (MINUSCA) demanded they leave the town to avoid further bloodshed. The group then established a base in Alindao, in Basse-Kotto province, from where they continued to attack civilians in the region. UPC fighters and local Muslims killed at least 136 civilians over two days when they attacked the Paris-Congo and Banguiville neighborhoods in Alindao in May 2017 after people reported the presence of anti-balaka fighters in the area. At least 32 civilians were killed by the UPC in August as they tried to leave the town’s displacement camp in search of food and firewood.[24]

Humanitarian needs are dire, with an estimated 50 percent of the population dependent on humanitarian aid and some 2 million people facing extreme food insecurity.[25] A resurgence of violence between January and July led to revision of the Humanitarian Response Plan for 2017. At time of writing, less than 24 percent of the UN’s US$497 million humanitarian appeal for 2017 had been funded. Internal displacement had risen to around 600,000 as a result of increased violence, and around 2.4 million people—nearly half the population—depend on humanitarian aid to survive. At the same time, over 200 attacks on aid workers during the first six months of 2017 made it one of the most dangerous countries for humanitarian actors to operate and hindered provision of critical assistance.[26] Women and girls told Human Rights Watch about sexual violence that occurred while they were seeking resources or work, saying they had no choice but to venture out in order to support their families.

International Intervention

In late 2013, the African Union (AU), which had contributed peacekeeping forces in the country since 2002, authorized a more robust peacekeeping mission, the International Support Mission to the Central African Republic, known as MISCA. Shortly thereafter, France added soldiers to its small Bangui-based force to help the AU restore order.[27]

Violence continued despite the AU and French troops, and in April 2014 the United Nations Security Council authorized a new peacekeeping mission called the Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in the Central African Republic, known by its French acronym, MINUSCA. The mission had a multi-pronged mandate: protecting civilians; facilitating humanitarian access; monitoring, investigating, and reporting on human rights abuses; and supporting the political transition.[28] MINUSCA took over from MISCA on September 15, 2014, with 11,820 military personnel. French troops remained in the country until October 2016.

The UN Security Council Resolution that established MINUSCA prioritizes protection of civilians “from threat of physical violence,” including sexual violence.[29] Under its human rights mandate, MINUSCA is tasked with monitoring, investigating and reporting on all forms of sexual violence in the conflict, preventing such abuses, and helping to identify and prosecute perpetrators.[30] MINUSCA is authorized to use all necessary means to carry out its mandate in its areas of deployment.[31]

The resolution calls on all parties to the conflict, including both Seleka and anti-balaka, “to issue clear orders against sexual and gender based violence.”[32] It appeals to authorities to ensure timely investigation of abuses and “facilitate immediate access for victims of sexual violence to available services.”[33]

In December 2013, the Security Council created a panel of experts to track developments in the Central African Republic, monitor sanctions implementation, and identify potential targets for sanctions.[34] In January 2017, the Security Council revised the criteria for designation to include involvement in planning, directing, or committing sexual violence as a specific criterion for sanctions.[35] At time of writing, no individuals or entities have been sanctioned for planning, directing, or committing sexual violence in the Central African Republic's civil war.[36]

As of May 2017, MINUSCA had 9,885 troops and 1,806 police deployed in the country.[37]

Lack of Accountability

President Touadéra’s government inherited a broken national justice system, with little capacity to investigate and prosecute serious crimes, let alone war crimes or crimes against humanity committed by armed groups.[38] Efforts to rebuild the judicial system have been painfully slow, hampered by ongoing insecurity—including in areas where armed groups retain control—lack of infrastructure and supplies, and limited capacity and training of police and judicial officials. The country has 198 magistrates—many of whom have not resumed their posts since the Bozizé government fell—and 80 lawyers, most of whom are based in Bangui.[39] Judicial police often fail to investigate criminal cases.[40] The detention system is in shambles: while there were 28 detention centers nationwide before the current crisis, at time of writing only six were in operation, two of which are in the capital.[41] Mass escapes have occurred at several of the remaining prisons.[42]

Historical impunity for sexual violence casts a shadow over the judicial system. In its May 2017 review of human rights violations in the country between 2003 and 2015, the United Nations describes the conflict-affected Central African Republic as “an environment in which perpetrators of sexual violence enjoy unbridled impunity as a result of widespread insecurity and dysfunctional or collapsed institutions, a situation which persists to date.”[43] To accelerate the processing of some criminal cases, in 1998 the General Prosecutor ordered re-classification of offences—including rape—to allow for their trial in civil courts, where sanctions are less harsh than in criminal courts.[44] This order remained in place until March 2016, when the minister of justice instructed judges and court officials to cease this practice for cases of sexual violence, noting concern over high rates of the crime and the lack of accountability.[45]

Criminal trials should take place during special criminal sessions held twice per year in one of four appeals courts throughout the country.[46] However, no criminal trials took place between 2009 and 2014. With the support of MINUSCA and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), criminal court sessions adjudicated criminal cases in Bangui in June 2015 and in August and September 2016.[47] Only three rape cases—none perpetrated by members of armed groups—were prosecuted during the 2016 criminal sessions.[48]

The International Criminal Court (ICC) has launched an investigation into grave crimes committed during the conflict in the Central African Republic since 2012. At time of writing, the investigation was ongoing and no charges had been issued. The ICC’s investigation offers the chance to bring a measure of accountability for crimes but will likely try only a small number of cases.

A 2015 law establishing a Special Criminal Court (SCC), a hybrid national and international court embedded in the national justice system, also offers hope of accountability for serious crimes committed during the current conflict.[49] While a special prosecutor was appointed to the SCC in February 2017, and international and domestic judges were appointed in subsequent months, the court has been slow to become operational; in addition, only the first year of the court’s five-year mission had been funded at time of writing.[50]

Sexual Violence in the Conflict

From the beginning of the conflict in December 2012, the United Nations Special Representative on Sexual Violence in Conflict has noted “consistent reports” of sexual violence, particularly in areas where armed groups were present or had control.[51] In annual reports on sexual violence in conflict from 2013 to 2017, the UN Secretary-General has highlighted the use of sexual violence by armed groups to terrorize and punish civilians in the Central African Republic, saying that “women and girls have been systematically targeted.”[52] In his 2016 report on children and armed conflict, he noted sexual violence against girls by armed groups, including as sex slaves, and impunity for perpetrators.[53] The 2017 report referred to “a pattern of conflict-related sexual violence of an ethnic and sectarian nature” in the Central African Republic, with incidents perpetrated by both Seleka and anti-balaka forces, at times “aimed at humiliating or punishing the target population.”[54]

An International Commission of Inquiry, tasked by the UN Security Council in December 2013 with investigating international human rights and humanitarian law violations in the conflict, reported evidence of rape, gang rape, and other forms of sexual violence at the hands of both Seleka and anti-balaka fighters between January 1, 2013, and November 1, 2014.[55] “The widespread nature of these forms of violence is undisputed,” the Commission said.[56] In July 2017, the Panel of Experts on the Central African Republic affirmed the ongoing nature of the problem, saying that sexual and gender-based violence are “a recurrent and widespread phenomenon in the entire country.”[57]

In its 2014 review of the Central African Republic, the UN Committee that monitors implementation of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW Committee) pointed to the government’s longstanding failure to ensure non-discrimination and to address gender-based violence as contributing factors to conflict-related sexual violence.[58]

The absence of systematic data collection has hindered attempts to assess the scale of the problem. The United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), which leads the humanitarian coordination group on gender-based violence (the GBV sub-cluster) and GBV information management system, registered 11,110 cases of sexual and gender-based violence between January and December 2016, of which 2,313 constituted sexual violence. Non-state armed actors committed approximately 12.5 percent of total incidents, but the information is not disaggregated to show the number of cases of sexual violence (versus other gender-based violence) perpetrated by armed men.[59] The UN Secretary-General’s 2017 annual report on sexual violence in conflict states that MINUSCA recorded 179 cases in 2016, perpetrated by a variety of armed groups.[60] The Panel of Experts reported receiving information about 59 cases of rape throughout the country between January and July 2017, but noted persistent underreporting of sexual violence.[61]

Data discrepancies result from multiple factors, including inconsistent definitions of “conflict-related sexual violence,” varied methods for collecting and verifying information, and differing capacities across UN and non-governmental agencies. In her July 2016 report, the UN’s Independent Expert on the Central African Republic noted that such inconsistencies point to a need for greater attention from national authorities and the international community to sexual and other gender-based violence. She expressed concern that the lack of reliable data would harm efforts to provide services for survivors and combat impunity.[62]

Prior to the Bangui Forum on Reconciliation, Reconstruction and Durable Peace in May 2015—intended to launch initiatives on reconciliation, disarmament, and the reassertion of state control—over 200 female leaders from across the country participated in a consultation organized by the transitional government. The women identified conflict-related sexual violence as a key priority, and called for an end to impunity for perpetrators as well as greater access to justice and services for survivors.[63] Their first recommendation was that all parties to the conflict respect prior peace accords and “put an end to human rights violations against the civilian population, and especially sexual violence.”[64]

II. Sexual Violence against Women and Girls by Armed Groups

Both Seleka and anti-balaka fighters have committed widespread sexual violence in the ongoing Central African Republic conflict, with Human Rights Watch having documented cases that occurred as recently as May 2017. Women and girls told Human Rights Watch of sexual slavery and rape, usually by multiple perpetrators, accompanied by physical violence and acts of humiliation. Perpetrators beat women and girls, tied them up, burned them, and raped them with objects. When anti-balaka or Seleka fighters held women as sexual slaves, survivors said fighters typically raped them repeatedly for days or even months on end. The fighters also forced women and girls to do domestic work and sometimes laid claim to them as “wives.”

Survivors said that fighters sometimes forced their husbands to watch their rapes, or that their children witnessed the violence. In some cases, survivors saw armed groups torture, kill, and dismember their husbands or family members before or after the sexual violence. In one instance, a survivor said fighters raped her husband, forcing her to watch, before killing him and raping her. Multiple women and girls said fighters raped them while they were pregnant.

Women and girls frequently described armed groups using sexual violence as punishment, usually because of a perceived affiliation with a rival faction. Perpetrators often targeted women and girls on the basis of their presumed religious affiliation—using it as grounds to assume support for opposing fighters—as well as for allegedly conducting trade across sectarian lines, or because of their husbands’ or family members’ purported allegiances.[65]

Human Rights Watch documented several clusters of sexual violence incidents linked to specific attacks or periods of violence, as well as isolated cases in different locations or during different time periods. The annex at the end of this report shows the location, date, and armed group with which the perpetrators of sexual violence were affiliated for each case documented. As noted above, given underreporting of sexual violence and limited access to some areas, the cases documented here do not in any way purport to be a comprehensive account of all incidents across the country, but more likely only reflect a fraction of such assaults.[66] The United Nations, for example, recorded over 2,500 cases of sexual violence in 2014 alone. [67]

Sexual Slavery and Forced Labor

Since early 2013, both Seleka and anti-balaka forces have raped women and girls—often repeatedly and by multiple assailants—and also held them captive, denied them liberty, and forced them to do domestic work. Under international law, these offenses amount to sexual slavery and may be considered crimes against humanity and war crimes.[68] According to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, sexual slavery occurs when a perpetrator commits at least one act of sexual violence and exerts “ownership” or control over the victim through sale, exchange, or deprivation of liberty.[69] The UN Special Rapporteur on Contemporary Forms of Slavery has noted that, as per the 1926 Slavery Convention, the right of ownership in “slavery” may be exhibited by “sexual access through rape or other forms of sexual violence.”[70]

Human Rights Watch interviewed 44 women and girl survivors of sexual slavery, who said that they were held captive with a total of at least 167 other women and girls who were also sexual slavery victims. In two cases, armed groups held the women and girls for over a year. Thirty-five of the 44 women and girls said that multiple men raped them repeatedly, sometimes every day. At least nine survivors became pregnant during the time they were held as sexual slaves, including girls aged 14 and approximately 16 at the time, and at least five gave birth to children from the rapes.[71]

Human Rights Watch documented physical and psychological abuse of women and girls held captive by both anti-balaka and Seleka fighters that may amount to torture.[72] This included hitting women and girls with whips, tying them up for prolonged periods of time, burning them with hot plastic, and threatening them with death.

Sexual Slavery by Seleka

Human Rights Watch interviewed at least 18 survivors of sexual slavery who were taken by Seleka fighters between late 2013 and mid-2017.[73] Fourteen incidents occurred in and around Bambari, including eight cases during or just after an assault on the town in June 2014 (see “Sexual Slavery by Seleka fighters in Bambari”).[74] Three of the survivors gave birth to babies conceived while they were held as sexual slaves.

Human Rights Watch also documented Seleka forces holding a woman as a sexual slave in Bangui, another near Baoro, another near Bossangoa, and another in Kaga-Bandoro.

Women and girls subjected to sexual slavery described recurring sexual violence and forced labor. Victoire, 39, told Human Rights Watch that Seleka fighters took her and four other women to a camp in Bambari in mid-2014. She said that during the month she spent there, multiple fighters raped the women and the fighters’ commander took her as his “wife”:

They [the Seleka] were many. Each one took us turn by turn. Each one raped us each day, one by one…. The chief came, saw me, took me and put me to the side. After that, he raped me, every day. If he didn’t go out [of the camp] he would do it to me three times in a day…. [When] they demanded sex from a woman, if she refused, they hit her, beat her.[75]

Sophie, 22, said that two different groups of Seleka fighters held her as a sexual slave in separate incidents. After the Seleka burned down her family home in Bambari around June 2014, Sophie fled into the bush with four other young women. She described how Seleka fighters caught the group and kept them captive in the forest:

They gave us work to do. Sometimes preparing food, doing the laundry. Sometimes when you were preparing food they would come and three of them would rape you. They did that three or four times a day, several men—different men…. All five girls were raped like this.[76]

The young women escaped a week later, but after two months in a village, another group of Seleka caught them. “Four of them took me and threw me on the ground. They started taking turns raping me,” Sophie said. She said she saw the Seleka push pieces of wood into the vaginas of two young women who refused to sleep with them, killing the women. For three days, she said, Seleka fighters repeatedly raped her and the other surviving women and forced them to prepare food and draw water. She said that at least 12 fighters raped her during that time.[77]

Some women told Human Rights Watch that Seleka fighters targeted them because of their religion. Denise, 20, said that Seleka fighters seized her in December 2014 while she was going to buy vegetables in Bangui’s Boeing neighborhood. The Seleka said, “You are a woman of a balaka,” and insulted her for being Muslim. Four fighters raped her and tied her to a tree, she said, before bringing her to a compound in the Ramandji neighborhood where they held her for two days with 10 other women they had taken from Boeing and raped.[78]

The Seleka also targeted women and girls because of their families’ perceived support for the anti-balaka. Noelle, 25, said that Seleka fighters found the family in their fields about 25 kilometers from Baoro on the Baoro–Bangui road in December 2013, and accused her brother, who sold bullets, of providing ammunition to anti-balaka forces. “They tied up me and my sister-in-law,” she said. “They started to torture us with the butts of their guns. They hit us on the head and stomped on us with their feet…. The five who took us started to rape me, all five of them.”[79]

Sexual Slavery by Seleka in Bambari

Since June 2014, multiple attacks in and around Bambari, the capital of the Ouaka province, have led to mass civilian displacement as well as injury and death. By June and July 2014, control of Bambari was split between rival Seleka forces that would eventually become the RPRC (Rassemblement Patriotique pour le Renouveau de Centrafrique), led by Gen. Joseph Zoundeko, who was installed as the military commander of the then-unified Seleka in May 2014, and the Union for Peace in the Central African Republic (UPC), which Gen. Ali Darassa Mahamant created in September 2014 with himself as president and commanding general.[80] The UPC retains control of parts of the Ouaka province. Darassa’s UPC repeatedly targeted civilians they believe to be allied or affiliated with the anti-balaka.[81]

On June 9, 2014, Seleka fighters and ethnic Peuhl attacked Liwa, a predominantly Christian village 10 kilometers south of Bambari. Witnesses and victims’ family members told Human Rights Watch that fighters shot and hacked people to death as they tried to escape. The entire village of 169 homes was destroyed.[82]

The assault on Liwa set off a cycle of reprisal attacks in neighboring communities, culminating in Seleka attacks on Christian neighborhoods in Bambari in late June that left at least 32 dead.[83] On July 7, Seleka fighters attacked Bambari’s Saint Joseph’s Parish, where thousands of displaced had taken shelter, killing at least 27 people.[84]

Human Rights Watch documented 14 cases in which Seleka fighters held women as sexual slaves in and around Bambari between late 2013 and late 2015. Seven survivors told Human Rights Watch that Seleka took them from the Kidigra neighborhood in Bambari during attacks in late June and early July 2014, and one said she was held by Seleka in that neighborhood.

The Seleka held the women, then aged between approximately 20 and 73, for periods ranging from three days to over a year. Survivors said that at least 89 other women and girls held with them also endured sexual violence and forced work. All of the women were raped by multiple men, often repeatedly on different days. Two survivors described how streams of various fighters raped them when they rotated through the bases where the women were held. One told Human Rights Watch that on her first day in captivity, about 15 men raped her and four other women.[85]

Jeanne, 30, said that a group of 20 Seleka caught her and nine other women and girls—some as young as 16—as they fled when the Kidigra neighborhood came under attack in June 2014. She said the Seleka held her at a base for six months:

The first day, five Seleka raped me. Every day we could not rest—every day there was rape, by different fighters.… We became their wives. Each fighter who arrived at the base, it was to rape us. If we refused, they hit us…. I went to look for firewood. I drew water, looked for water at the river, prepared their food. All of the women did this. All the women were raped each night.[86]

Five of the women and girls became pregnant, but had no means to terminate the pregnancies, Jeanne said. “In the bush, what could they do?” Jeanne asked. “They had to keep the pregnancy. The Seleka didn’t react. They still raped the pregnant women.”[87]

Other survivors also found that pregnancy did not shield them from sexual violence. Angèle, 27, became pregnant and gave birth to a child as a result of repeated rape after Seleka fighters took her near Bambari in June 2014 and held her in sexual slavery for nine months with five other women and girls. She said the Seleka “considered us like their wives:”

[At the base] we prepared the food. If we didn’t prepare it very well, they hit us with the butts of their guns. They [also hit us with] whips they used for horses…. During the day, they did it [rape] one time. At night, it was another [fighter] who would call us. We would think it was to prepare the tea, but it was to rape us.[88]

Angèle said that the Seleka fighters raped her vaginally and anally, and continued to do so during her pregnancy. “They said we are their slaves,” she recalled.[89]

In some cases, survivors said that they watched Seleka fighters kill their family members. Christine, 63, said the Seleka murdered her husband and subjected her to sexual and physical violence in June 2014 as the couple fled the Kidigra neighborhood in Bambari:

Those who raped me, I don’t know their number exactly. I tried to scream but they shut my mouth with their hands and started to rape me one by one. When I said I was tired, they didn’t care. They started to punch me. When they finished raping me, they took the cloth off [that they had used to cover] my eyes. They showed me the corpse of my husband. They had cut his throat.[90]

Christine said the Seleka held her for five days with young girls whose ages she did not know.[91]

Girls were also subjected to sexual slavery. Martine, 32, said that Seleka fighters took her and around 19 others, including girls, during the July 2014 attack on St. Joseph’s Parish and held them in the bush near Bambari for two weeks. “There were young girls [who were] 12 years old,” she said. “We spent a week with ropes around our feet and hands…. They untied us to have sex. Then, after they finished, they tied us up again…. There were four or five different people [raping us] each day.”[92]

Henriette, 50, told Human Rights Watch that in June 2014, around 15 Seleka fighters broke into her home in the Kidigra neighborhood, raped her, and held her and her 6-year-old daughter captive. “Nearly 10 of them raped me,” she said. “In the bush I became their domestic worker, drawing water. I was there with my youngest daughter. They gave her little jerry cans also to draw water.”[93]

Human Rights Watch also documented 22 cases of rape without sexual slavery committed by Seleka and Seleka-Peuhl fighters in and around Bambari between December 2013 and December 2015 (see “Rape by Seleka in Liwa and Bambari”). The Seleka and UPC, under the command of Darassa as their local leader, maintained control of large parts of the Ouaka province, including Bambari, from the start of the crisis until January 2017.

In June 2014, General Zoundeko told Human Rights Watch that no Seleka fighters took part in fighting in Liwa or Bambari.[94]

In a September 2014 meeting with Human Rights Watch, Ali Darassa denied that his men were involved in any fighting around Bambari in June and July 2014.[95] While some reports indicate that Darassa was not in control of all armed Peuhl in Bambari in mid-2014, multiple witnesses to the attack on St. Joseph’s church told Human Rights Watch that they recognized men they understood to be under Darassa’s control among the attackers. [96] In January 2016, Darassa told Human Rights Watch that all of his fighters are aware that certain actions, including sexual violence, are crimes under international law, and that they have never committed rape. He said: “Our fighters are known by everyone. We have never received any complaints [of rape], so one can say that the fighters respect the law.”[97]

Sexual Slavery by Anti-Balaka

Human Rights Watch interviewed 26 women and girls who were held as sexual slaves by anti-balaka between December 2013 and April 2016, primarily in Bangui and Boda. Like those who suffered sexual slavery by the Seleka, the survivors described repeated rapes, often by multiple assailants, as well as beatings, humiliation, and being taken as fighters’ “wives.”[98]

Anti-balaka held five females, including girls as young as 12, as sexual slaves in and around Boda, about 100 kilometers west of Bangui, where the anti-balaka had a well-known base near the Catholic mission (see “Rape by Anti-Balaka in and around Boda”). Human Rights Watch also documented cases in which the anti-balaka held six women and girls as sexual slaves in Bangui, two near Yaloké, and another in Bambari, and captured three women on the Oubangui River between Mobaye and Bangui, another on the road to Mbaïki, and another on the Bouar road near Baoro, all of whom they then held as sexual slaves.[99]

The length of survivors’ captivity ranged from a few days to well over a year. Amira, 16, said that anti-balaka held her near Yaloké, in the Ombella-M’poko province, for 18 months beginning around February 2014, along with two other Muslim women who suffered similar abuse, one of whom was pregnant at the time.[100] Amira described how the anti-balaka hit her with a whip and a machete, subjected her to repeated gang rape, and made her do housework:

They raped me. Four of them. They did it again every night, always the four of them…. They also hurt me physically. Always with the whips, they hit me. There was forced labor. They made me draw water, prepare the food to eat, do the dishes. They talked about me as their wife.[101]

Virginie, 16, and Patricia, 22, said in separate interviews that anti-balaka abducted them individually while they were selling cassava leaves at a market in Bangui in April 2016 and brought them to a nearby base. Virginie said that anti-balaka held her there for five days, during which time they raped her, hit her with a whip, and punched her when she cried:

They could have sexual relations five times a day if their commander left. The same three men [raped me] during the night. When I slept deeply they did it also—once per person—and [then] they left me. They did this all five days.[102]

Patricia said that two anti-balaka fighters raped and beat her at the base for two days. When she tried to flee, the anti-balaka caught her, tied her up, and left her overnight.[103]

Like Seleka fighters, members of the anti-balaka targeted women because of their presumed religious affiliation or that of their relatives. Leila told Human Rights Watch that anti-balaka took her near Baoro in April 2016 because her husband is Muslim. “They cut my breast, put a knife to the throat of my baby and said they would kill him because my husband is Muslim and the baby is Muslim,” she said.[104] Leila said the anti-balaka held her for two days with nine other women and girls, raping them repeatedly in front of each other.[105]

Rachida, 25, said that anti-balaka took her hostage as she exited the Muslim PK5 neighborhood in Bangui to sell vegetables in August 2015. She said they held her for three weeks at St. Denis Church in the third arrondissement towards the Kattin neighborhood, raping her repeatedly and accusing her of fraternizing with Muslims:

Each day, four men came to have sex with me in the morning. Then five men at 3:00 p.m. and again at 7:00 p.m. In the morning four men, in the afternoon and evening, the commander plus four men…. They said, “You look like a Christian girl. You sell your sex to Muslims. Today you will see.”[106]

Rachida said the anti-balaka held four other young women with her in the church and raped each of them three times a day. She said the men killed one of the women. “They dug a grave and they put her in it, alive,” she said.[107] At the time of her interview with Human Rights Watch, Rachida was pregnant due to the rapes.

Many survivors said that, like the Seleka, the anti-balaka referred to women and girls in captivity as “wives.” Caroline was around 17 years old when 15 anti-balaka fighters took her and four others to a base in Boboua village, near Boda on the road to Mbaïki, in late 2013, where they were already keeping more than 10 young girls, and raped them all. “They said we killed their relatives so they’ll take us for marriage and we’ll become their own wives,” Caroline recalled.[108]

Human Rights Watch interviewed eleven girls who were between the ages of 13 and 17 when anti-balaka fighters held them as sexual slaves; they said that at least 20 other girls were held with them, some as young as 12.[109] Thérèse, 14, said that she and her younger sister were returning to Boda in early 2014 after collecting cassava when anti-balaka fighters captured them, brought them to their base, and held them for two days with eight older girls. Thérèse described how the anti-balaka accused them of providing food to Muslims and raped them:

I was 13, my sister was 12. They took me and my sister, took off our clothes, threw us on the ground and started to rape us…. They said, “We are suffering because of you, because you take the cassava and sell it to the Muslim community—you are traitors.” There were four anti-balaka. Among the four, three raped us.[110]

In some cases, anti-balaka fighters appeared to hold women for domestic servitude. In separate interviews, Joséphine, 40, and Annette, 27, said that anti-balaka captured them and another woman in March 2016 as they were returning to Bangui by river from the market in Mobaye. The anti-balaka stopped their boat, demanded payment, and took their merchandise before forcing the women to walk several hours into the bush and holding them for four days. Annette explained how the anti-balaka abused the women and used them for domestic work:

The men said, “We brought you here to prepare food for us because out here in the bush we don’t have anyone to do that work for us.” When we arrived, they started to beat us. They took a cord and tied my knees together. They then started to tie my hands behind my back. I started to cry out and they hit me in the face with the butt of a gun. The hit knocked my two front teeth out. I was shocked after the blow and a man ripped my clothes off. I started to bleed out of my mouth a lot…. [One of the men] pulled the cord off my legs, but my hands were still tied behind my back. He then raped me.[111]

Annette, who was missing her two front teeth when she spoke with Human Rights Watch, said she also saw three of the fighters stuff the other women’s mouths with cloth and rape them. The anti-balaka forced the two uninjured women to do domestic work and raped Joséphine repeatedly. “I became their wife,” Joséphine said. “They said with their own mouths that it had been a long time since they had had the chance to rape a woman.”[112]

Human Rights Watch documented cases in which multiple survivors identified three known anti-balaka leaders as those perpetrating or commanding perpetrators of sexual violence: Rodrique Ngaïbona, alias Andilo (see “Sexual Slavery by Anti-Balaka Under Rodrique Ngaïbona, alias Andilo”); Alfred Yékatom, alias Rombhot; and François Wote.

Sexual Slavery by Anti-Balaka Under Rodrique Ngaïbona, alias Andilo

In separate interviews, five survivors named Andilo, the alias of Rodrique Ngaïbona, as the fighter or commander of the fighters who raped them. Fighters under Andilo’s command participated in anti-balaka counteroffensives in 2014, including active combat with the Seleka around Andilo’s hometown of Batangafo in the Ouham province and in Bangui’s Boy-Rabe neighborhood. In 2014, the UN Panel of Experts named him “the most enigmatic, feared and powerful military commander of the anti-balaka.”[113] The national prosecutor issued a warrant for his arrest in May 2014. After MINUSCA peacekeepers detained him on January 17, 2015, in Bouca, about 195 miles north of Bangui, Andilo’s men undertook a series of high-profile kidnappings, demanding his release. [114]

At time of writing, Andilo is held in Camp de Roux detention center in Bangui, a facility for detainees designated as extremely dangerous. He had not been formally charged or put on trial, despite reaching the pre-trial detention limits prescribed by Central African law.[115]

Four survivors told Human Rights Watch they were traveling to sell goods in mid-2014 when anti-balaka stopped their vehicles north of Bangui.[116] Three of the four women said they saw and recognized the group’s leader as Andilo; one said she was taken as Andilo’s “wife.”

Sabine, 43, was traveling with a group including her husband when anti-balaka fighters stopped their vehicle. She said that Andilo and the other fighters—who referred to Andilo as “chief”—called the women’s husbands “Muslim criminals” before slitting her husband’s throat and tying her up.[117] Three of the anti-balaka raped her and brought her to their base, Sabine said, where Andilo took her as his “wife” and subjected her to sexual slavery for nearly seven months. She explained:

He told me if I don’t have sex with him he would kill me. He did it every day. If he wasn’t tired, it was multiple times a day. If I said I was tired, he would hit me. When he went out to go somewhere and he spent three or four days out of the base, I could rest. But when he came back, [resting] was finished. It was like that all six to seven months…. I couldn’t do anything but give in.[118]

The anti-balaka also stopped Zara and Prudence, both 28, with Sabine. Prudence said that she saw Andilo give the other fighters orders after they had stopped the vehicles. Zara said that approximately 30 anti-balaka held the women at gunpoint and accused them of supporting the Seleka. “They said to us, ‘All the merchandise that you buy is to resell to the Seleka and when they have eaten, they are going to come with force and kill us all with our families,’” Zara said.[119] Prudence also recalled how the anti-balaka claimed the women were feeding the opposition, saying, “It’s you who are nourishing the Seleka.”[120]

The anti-balaka accused the women of hiding money in their genitals, and raped and physically abused them, Zara said. She showed Human Rights Watch scars above her breast where she said they burned and cut her. She explained:

They said, “Get out the money that’s in your vagina,” and they started to cut our bodies with a knife. [They cut me] on the chest, on my knees.… Two men raped me, one after the other, in the vagina. One did it twice. When one left, I lost consciousness. They took water and poured it on me to wake me up. I don’t know what happened after that. When I woke up, I was soaking wet and I was in the mud…. I didn’t have the strength to get up off the ground. My body was all soaked in blood from where they cut it.[121]

Zara said the anti-balaka released her after two days while Prudence said the fighters held her for six months. Prudence said that, during her captivity, she saw Andilo come and go at the base, and that two fighters under his control took her as a “wife.”[122]

Noémie, 26, who was captured with Zara, Prudence, and Sabine in July 2014 and held as a sexual slave for seven months, also said that she saw Andilo at the base and that he commanded the anti-balaka fighters who held them with about 12 other women. She said two different anti-balaka fighters raped her up to three times a day, with one taking her as his “wife,” and tortured her. “They would hit me with a whip used on cows,” she said. “The colonel would shoot his gun in front of my face and tell me to admit that I was going to sell things to the Seleka.” [123]

Noémie said that she tried to escape at one point, but the anti-balaka fighters caught her, beat her severely, and melted plastic on her.[124] She showed Human Rights Watch scars consistent with burns. Noémie became pregnant in captivity and the anti-balaka released her when she was five months pregnant. She does not know who fathered her daughter, 11 months old at the time of the interview, and cried as she said, “When I look at the baby, I think of the violence that was done to me.”[125]

A fifth survivor also said that an anti-balaka fighter under Andilo’s command took her as his “wife” and raped her repeatedly around October or November 2015. Béatrice, 18, said that the fighter killed some of her relatives and then said, “I am going to take you as a wife and if you refuse I will kill you.”[126]

The fighter raped Béatrice four times in 24 hours and told her to come with him to his hometown. When he left her in the house, she escaped into the bush. She became pregnant from the rape, and wanted to terminate the pregnancy but did not know how to get an abortion and had not accessed medical care when she spoke with Human Rights Watch.[127] Béatrice’s attacker later ran unsuccessfully for parliamentary deputy of Bouca in the national elections in January 2016.[128]

In one case, a survivor told Human Rights Watch that anti-balaka fighters made her a sexual slave out of vengeance for the earlier arrest of their commander, Alfred Yékatom, alias Rombhot. A master corporal in the national army before the conflict, Rombhot promoted himself to “colonel” when he became a key anti-balaka leader in 2013. On June 23, 2014, Sangaris troops arrested Rombhot, but released him shortly thereafter. On August 20, 2015, Rombhot was added to the United Nations Security Council Committee’s sanctions list for undermining national peace and security by “engaging in or providing support for acts … that threaten or impede the political transition process … or that fuel violence.”[129]

One sexual slavery survivor told Human Rights Watch that she and five other women and girls were held, repeatedly raped, and forced to work for three days in April 2016 by men who said they were under Rombhot’s command. Alice said that anti-balaka fighters stopped the vehicle she was riding in with her husband on the Mbaïki–Bangui road, near Rombhot’s home town of Mbaïki, where he is known to operate a base. “They said they are fighters of Rombhot,” Alice said. “Because Rombhot was arrested, [the men said] if they see people on the road they will hurt them.”[130]

Alice said the anti-balaka brought her to a base where she was held with five other women and girls, some around 15 years old. “They said if I try to flee they were going to kill me,” she said. “I was raped for two days. On the second day, two of them continued to rape me. The two did it one by one in the morning, and one by one in the evening.”[131] She said the anti-balaka fighters also hit the women and girls with belts and forced them to wash clothes and cook until they escaped after three days.

In January 2016, Rombhot won the parliamentary seats representing Mbaïki in Lobaye province. The United Nations Panel of Experts cited evidence of Rombhot “intimidating voters and harassing political competitors in his constituency,” but national authorities could not stop his candidacy or invalidate the election results because no national warrant had been issued for his arrest and he had not been convicted of any crime.[132] Despite remaining on the UN Security Council Committee’s sanctions list, Rombhot has retained his parliamentary seats. The addition of sexual violence as a criterion for UN sanctions designation in January 2017 could provide clear rationale for retaining Rombhot on the sanctions list, regardless of whether he is perceived to be playing a constructive role politically. Introduction of vetting procedures for public office holders could force him to forgo his parliamentary seats, and would prevent those who have participated in or tolerated conflict-related sexual violence by those under their command from taking office.

In April 2015, Human Rights Watch documented the case of two Peuhl sisters held as sexual slaves for 14 months in 2014-2015 by anti-balaka fighters under the command of François Wote in the southwestern village of Pondo, near Yaloké, in the Ombella-M'poko Province.[133] During research for this report, Human Rights Watch documented two additional cases in which anti-balaka fighters held a 16-year-old girl and a 27-year-old woman separately near Yaloké.

Amira, 16, and also Peuhl, said that anti-balaka held her captive for 18 months beginning around February 2014, though she did not identify them specifically as Wote’s men. Amira described how the anti-balaka hit her with a whip and a machete, injuring her back, subjected her to repeated gang rape, and made her do household work. “They raped me. Four of them. [T]hey did it again every night, always the four of them,” she said.[134] When they released her, she said, she discovered she was pregnant from the repeated rapes.

Amira told Human Rights Watch that the anti-balaka held two other Muslim women at the house, one of whom was pregnant. She said that they beat the pregnant woman severely, and that the woman confided that the anti-balaka had raped her as well.[135]

François Wote, an anti-balaka commander in Pondo, near Yaloké, from 2014 to May 2015, reported to Guy Wabilo, the zone commander of the Gadzi region. In May 2015, Wabilo told Human Rights Watch that he knew Wote was committing sexual slavery in Pondo. “Yes, they [the Peuhls] were there for 14 months and the women were raped by François Wote,” Wabilo said.[136] Wabilo also said that Wote was under the command of Patrice-Edouard Ngaïssona, one of several Central Africans who claim leadership of the anti-balaka.[137]

Rape

In the current conflict, both the Seleka and the anti-balaka armed groups have committed rape during targeted attacks on neighborhoods and villages and used rape to punish and terrorize women and girls as they performed daily tasks, such as going to and from markets and seeking food or firewood. Other violence against family members, including killings and dismemberment, accompanied rapes that Human Rights Watch documented, and perpetrators often committed rape in front of victims’ family members.

Rape by Seleka