January 29, 2016

To: Donors attending the “Supporting Syria and the Region” conference

Human Rights Watch welcomes the upcoming Syria conference. It is essential that it should deliver a greatly strengthened international effort to support desperate and vulnerable Syrians, both within the country and in neighbouring states, as well as those that have arrived in Europe or seek refuge there.

The conference will focus heavily on financial commitments and the need for more assistance for countries like Lebanon, Turkey, and Jordan, who between them are hosting 4 million Syrian refugees. Increased resources are certainly needed. But aid alone will not adequately address the range of challenges that Syrians face. Based on our research, described in detail in the attached memorandum, Human Rights Watch has identified a need for action in three areas, if Syrians are to be better protected and assisted and their rights upheld.

First, we urge donors to call on Lebanon, Jordan and Turkey to end current practices that violate the prohibition on refoulement and secure commitments to this at the conference. Although they are legally obliged to ensure that people fleeing Syria, including Palestinian refugees and other habitual residents of Syria, are able to seek asylum, Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey have all restricted entry to refugees from Syria in 2015 and pushed back asylum seekers or forcibly returned refugees, in violation of their international obligations.

Second, donors should call on host countries to end harsh registration requirements that are nearly impossible for most refugees to meet. In January 2015, for example, Lebanese authorities implemented new border entry regulations, denying entry to refugees fleeing armed conflict and persecution in Syria, and imposed costly and restrictive regulations, effectively barring most refugees from renewing their residencies in Lebanon. Refugees without legal status are liable to arrest, and the lack of status has often prohibited refugees’ access to livelihoods, healthcare, and education, worsening their economic and social conditions, and, in the process, increasing not alleviating the burden on the host community. The renewal process is itself often abusive and arbitrary. In May 2015, Lebanese authorities demanded that UNHCR stop registering Syrian refugees in Lebanon.

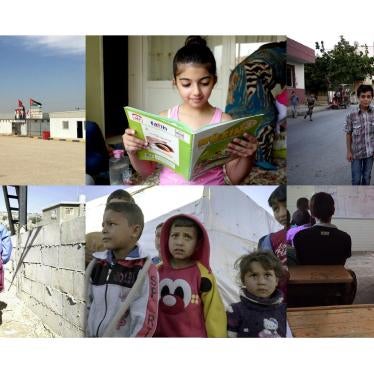

Third, we urge donors to work with host countries to lift existing barriers on access to education for Syrian children. These barriers include requirements that Syrian children produce official school certificates – which many families left behind when they fled Syria – in order to enroll in school. In Jordan and Lebanon, policies that subject Syrians to arrest and other penalties for lacking residency status or working without permits contribute to child labor and school drop-outs, since impoverished families see children as less at risk than adults for working. In January 2016, Turkey published a regulation that will allow some Syrians to apply for work permits. If the policy is fairly and rapidly implemented, enabling Syrians to support themselves, it should have significant benefits for refugee children. Donors should urge Lebanon and Jordan to make comparable changes that authorize refugees to work lawfully.

Education funding is needed for the infrastructure that supports schools, staff, teacher training, and support for Syrian families to cover costs such as transport fees. There is a lack of support programs or language assistance for Syrian children adjusting to new and difficult curricula, which are often taught in languages – such as Turkish and English – in which they have little or no education. Widespread corporal punishment has also led some Syrian students to drop out. Enrollment in secondary education is poor, and inclusive education for children with disabilities is often non-existent.

Countries outside the region, including members of the European Union, the United States, Australia, Russia, and the Gulf states, should share responsibility for hosting Syrian refugees with Turkey, Jordan and Lebanon, including by increasing safe resettlement opportunities. But resettlement should not be regarded as a substitute for asylum. European Union and other governments should ensure that Syrians and others seeking protection have the opportunity to present asylum claims at their land borders and ensure access to asylum for those present on their territory.

Refugees will not be able to return to Syria any time soon, no matter how hard life is in host countries or how perilous the journey to Europe. Financial pledges are a crucial response to the crisis, but by themselves not sufficient to resolve Syrians’ plight. A sustainable, comprehensive and effective response plan needs to include the specific policy changes that are addressed in the attached memorandum.

Thank you in advance for considering these proposals.

Sincerely,

Bill Frelick

Director, Refugee Rights Program

Memorandum to donors participating in the “Supporting Syria and the Region” conference, February 2016

January 2016

This conference is an opportunity to support Syrians at a time of desperate need. Human Rights Watch encourages donors to meet the conference’s stated goals by increasing and ensuring the sustainability of their support for Syrian nationals and Palestinian residents of Syria both within and outside Syria and for refugee host countries, creating economic opportunities and access to education for refugees and other displaced persons, improving capacity to address sexual and gender based violence, and pressuring parties to the conflict to protect civilians.

To succeed, participants in the conference should also address policies that, as Human Rights Watch has documented, undermine these goals by harming Syrian refugees whether they are staying in host countries, seeking resettlement, or seeking asylum in Europe.

As this memorandum describes, donors should take specific measures to pressure host governments to end harmful and abusive policies including border closures, pushbacks, and refoulement of asylum seekers; harsh registration requirements that are impossible for most refugees to meet; and restrictions on access to education. Donors including in the United States, European Union (EU) and Gulf states should share responsibility for hosting Syrian refugees with Turkey, Jordan, and Lebanon, including by increasing safe resettlement opportunities and increasing the capacity of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) to process resettlement cases. European Union governments should ensure that Syrians and others seeking protection in Europe have the opportunity to present asylum claims at EU land borders and ensure access to asylum for those present in EU territory.

Refugees will not be able to return to Syria soon, no matter how hard life is in host countries or how perilous the journey to Europe. Financial pledges are a crucial response to the crisis, but by themselves not sufficient to resolve Syrians’ plight. A sustainable, comprehensive, and effective response plan needs to include specific policy changes. Detailed information on harmful policies and recommendations to address them follow.

- Border closures, pushbacks, and refoulement

The United Nations refugee agency, UNHCR, stated in its latest country guidance on Syria that “all parts of the country are now embroiled in violence.” UNHCR has urged “all countries to ensure that persons fleeing Syria, including Palestinian refugees and other habitual residents of Syria, are admitted to their territory and are able to seek asylum.” Yet, in 2015, Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey all restricted entry to Syrian refugees and forcibly returned Syrian asylum seekers to Syria in violation of the customary international law prohibition on refoulement. Turkey has now introduced visa requirements for Syrians entering the country by air and sea. Donors concerned for the welfare of Syrian refugees should insist that host countries at minimum do not force them back to the war zone from which they are fleeing. Donors should also expedite the resettlement process and increase the number of places for Syrians in resettlement countries.

Jordan

Jordan has generously hosted more than 635,000 Syrians while the government estimates many more unregistered Syrians also live in Jordan. Jordan allowed Syrians to enter the country until mid-2013, but then closed its border near Syria’s most populated areas in the west, which forced Syrians to travel hundreds of kilometers to the far north-eastern part of Jordan, where some were allowed to enter.[1] In July 2014, Jordan also severely restricted entry at the north-eastern border crossings. Since then, thousands of Syrians have waited to reach Jordan’s asylum seeker transit sites for two to three months, in a demilitarized zone inside Jordan, several hundred meters south of the Syrian-Jordanian border. Asylum seekers are living in tents just north of a raised sand barrier, or “berm,” without adequate humanitarian assistance.

Although the authorities allowed people reaching the border to move onto the transit sites further inside Jordan in early 2015, authorities reverted to holding Syrians at the berm in March. Since then, Syrians – the vast majority women and children – have again remained stuck there for months, and border guards have only allowed a few dozen a day to reach the transit sites.[2] In January 2016, Jordan acknowledged that 16,000 people were stuck at the berm and stated that most would remain there for security reasons until other countries agreed to take them.[3][4]

Since late 2012, Jordan has systematically denied Palestinians from Syria access to the country and deported hundreds back to Syria.[5] Jordan has forcibly returned some Syrians to Syria without allowing them to claim asylum, as well as Syrians to whom the UN refugee agency issued asylum seeker certificates, in violation of the customary international law prohibition against refoulement.[6]

Donors should call on Jordan to:

- Stop holding refugees and asylum seekers at the berm and allow unimpeded humanitarian assistance to reach them there,

- End the policy of blocking entry to asylum seekers from Syria, including Palestinians, and

- End forcible returns of Syrians, including Palestinians from Syria, and maintain the temporary protection regime for all Syrians and Palestinians from Syria.

Turkey

As of December 2015, Turkey had registered over 2.5 million Syrians, of whom about 250,000 live in 25 camps managed by the Turkish authorities.[7] In September, Turkey said it had spent US$7.6 billion on assisting Syrian refugees since 2011. Yet Turkey has also closed its borders to people seeking asylum.

Despite sporadic border closures starting in 2012, Turkey allowed Syrians with and without identity documents to enter through official border crossing points until late 2014. However, since early 2015, Turkey has all but closed its borders to Syrians fleeing the conflict who have increasingly been forced to use smugglers to reach Turkey.[8] In late 2015, Turkish border guards intercepted Syrians who crossed to Turkey using smugglers at or near the border, in some cases beat them, and pushed them and dozens of others back into Syria or detained and then summarily expelled them along with hundreds of others.

In January 2015, Turkey introduced rules requiring Syrians to present valid travel documents to enter.[9] In January 2016, Turkey imposed visa requirements for Syrians wishing to enter the country by air or sea. The day the visa requirements came into force, at least 200 Syrians without Turkish visas were forcibly returned from Lebanon to Damascus by air after being refused permission to fly to Turkey.

Until early March 2015, Syrians crossed through the only two official border crossing points with Syria still open at that time.[10] On March 9, the Turkish authorities announced they were closing both crossing points and that only aid trucks and authorized traders could cross. As of mid-January 2016, the crossings had still not re-opened. Since March 2015, Turkey has allowed only two categories of people to enter through the two crossing points: gravely injured Syrians who cannot be treated in Syria, and Syrians registered with Turkey’s emergency relief agency who have been given special permission to go briefly to Syria before returning to Turkey.[11]

Until July 2015, Syrians continued to cross with smugglers into Turkey.[12] On July 22, two days after a suicide bombing by an individual trained by the extremist group Islamic State (also known as ISIS) killed 32 people in Turkey, Turkey announced it would take additional steps to secure its 822-kilometer border with Syria, including by building a 150-kilometer wall, reinforcing wire fencing, and digging a 365-kilometer trench. Since the end of July, Turkish border guards have increasingly prevented Syrians from crossing into Turkey, which has meant that most Syrians now cross through one informal crossing point that remains hard to police. Some camps for displaced persons inside Syria near the Turkish border are unsafe; Human Rights Watch documented Russian or Syrian government attacks using cluster munitions that hit one such camp in November 2015, killing at least seven civilians and injuring dozens.[13]

Turkey was the main transit route for Syrians and others seeking to reach the European Union. In November 2015, Turkey agreed to a migration action plan with the EU, undertaking to prevent irregular migration into the EU and into Turkey, in exchange for €3 billion (roughly $2.75 billion) assistance aimed at supporting Syrians in Turkey, reinvigorated negotiations over future EU membership, and the promise of visa-free travel for Turkish citizens in European countries participating in the Schengen free movement area. The agreement gave rise to concerns that Turkey would reinforce restrictions on access to its territory for Syrians and others in need of protection and subject those seeking to reach EU territory to abuse and impede their access to asylum.

Donors should:

- Call on Turkey to end practices that violate the prohibition on refoulement, including by preventing access to its territory for Syrians and summarily returning them to Syria.

- As applicable, carefully monitor their agreements with Turkey to limit the onward movement of asylum seekers from Turkey to assess whether they have led to unlawful Turkish practices, including prevention of asylum seekers from leaving Syria and loss of temporary protected status for those caught trying to cross into Europe, and revise those agreements as necessary to ensure no funding is supporting such practices.

Lebanon

Lebanon, with more than 1.2 million Syrian refugees, is hosting more refugees per capita than any other country. However, Lebanon has forcibly returned Syrians, including people who may have been refugees, in what appears to be a violation of its international obligations, and has imposed harmful residency requirements that few Syrian refugees can meet.

On January 8, 2016, Lebanese authorities returned at least 200 and perhaps more than 400 Syrians traveling through Beirut airport back to Syria without first assessing their risk of harm upon return there.[14] Human Rights Watch learned through actors present at the airport on January 8 that some passengers expressed a fear of return to Syria but that Lebanese authorities returned them anyway. Human Rights Watch previously documented the forcible return of four Syrian nationals to Syria on August 1, 2012, about three dozen Palestinians to Syria on May 4, 2014, and the forcible return or suspected return of three other Syrians that year.[15]

In January 2015, Lebanese authorities implemented new border entry regulations, denying entry to Syrians fleeing armed conflict and persecution, and imposed costly and restrictive regulations, effectively barring most refugees from renewing their residencies in Lebanon. In May 2015, the Lebanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs demanded that UNHCR stop registering Syrian refugees in Lebanon.

A recent report by Human Rights Watch documented that the regulations left most refugees without legal status, which often prohibited their access to livelihoods, healthcare, education, and shelter resulting in an unprecedented deterioration of their legal and socio-economic status and further burdening the host community.[16] Female refugees reported heightened risks of abuse and exploitation.[17]

Lebanon is in urgent need of greater international assistance, but refugee protection is essential. Absent the implementation of key policy changes by the Lebanese authorities, donor aid will fail to help Lebanon properly assist refugees or to promote greater stability in Lebanon by ensuring that Syrian refugees are not driven to destitution.

The regulations sort Syrians seeking to renew residency permits into two categories: those registered with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the United Nations refugee agency, and those who are not, who must find a Lebanese sponsor to remain legally in the country. All must pay a $200 annual fee for renewals – which most cannot not afford – and provide identification papers and documentation about their lodging.[18]

Human Rights Watch research has shown that the renewal process is itself abusive and arbitrary. For instance, many refugees who are registered with UNHCR told Human Rights Watch that General Security asked them to provide a work sponsor, even though regulations do not require it. Refugees and aid workers also said that some General Security employees and local officials use the renewal process to interrogate Syrians about security issues, and in some cases, to solicit sexual or financial favors.

Refugees without legal status may restrict their movement due to fear of arrest, affecting their ability to find work.[19] Nearly 90 percent are trapped in a cycle of debt, according to a recent United Nations assessment, and many have exhausted their financial reserves. Loss of legal status leaves refugees vulnerable to labor and sexual exploitation by employers, without the ability to turn to authorities for protection. Even those who do find sponsors do not benefit from protection under Lebanon’s labor laws and are vulnerable to those to whom they owe their legal status.

Human Rights Watch documented sexual assault, harassment, or attempted sexual exploitation of women and girls, sometimes repeatedly, by employers, landlords, local faith-based aid distributors, and community members.[20]

Refugees who are unable to work have less money for school transportation or supplies for their children’s schooling. Since children are less likely than adults to be stopped at checkpoints, more children are being sent to work to sustain their families rather than to school. Some work in dangerous conditions, and others drop out of school to work. Some school directors refuse to enroll children without valid residency, even though the Ministry of Education has indicated that residency is not required for enrollment. Newborn children are at risk of becoming stateless because their parents cannot obtain official birth certificates in Lebanon without legal status.

Donors should call on Lebanese authorities to:

- Ensure that no one fleeing Syria is forcibly returned or refused entry at the border,

- Lift the ban on UNHCR registration of Syrians who arrived after January 2015, and provide unrestricted access to UNHCR so that it can determine refugee status for any Syrian who expresses a fear of persecution if returned to Syria – even if the person is detained and was not registered with UNHCR at the time of detention,

- Waive residency renewal fees for all Syrians, waive the pledge not to work for Syrians registered with UNHCR, and cancel the sponsorship pledge for Syrians not registered with UNHCR,

- Allow Syrians without legal residency to regularize their status, and publish clear information about procedures needed for Syrians to renew their status,

- End the practice of detaining refugees because they do not have legal residency status, and

- Inform refugees who have been subject to sexual harassment and exploitation of how to file a complaint, ensure that claims are investigated and the abusers held accountable, and ensure that women who report sexual and gender-based violence are not prosecuted for immigration law violations; and dedicate funding and design programming to provide protection, along with medical and psycho-social support for survivors.

2. Access to Education

Lebanon

Despite a positive Back to School campaign launched in 2015, Lebanon’s latest Crisis Response Plan estimates that more than 220,000 children between the ages of 6-14 are still not in school.[21] There is an immediate need to fully fund formal education for all Syrian children in Lebanon. However, funding alone will not address all the serious barriers to education that Human Rights Watch has documented.

Human Rights Watch found that even when formal schooling is available at no cost, Syrian refugees are often unable to enroll their children. With 70 percent of refugees living below the poverty line and 89 percent in debt averaging $842, many families cannot afford the transportation costs or supplies required to send children to school. Others depend on child labor to feed their family and pay rent. Human Rights Watch also found that, contrary to government policy, individual school directors are imposing additional enrollment requirements, including valid residency, UNHCR registration, or medical records from Syria.

Several other factors deter Syrian enrollment and lead to drop-outs. Refugee families report widespread corporal punishment and discrimination against Syrian children in Lebanese schools. Many told Human Rights Watch in early December 2015 that their children had still not received textbooks several months into the school year, or complained that their children were not learning or understanding school lessons. There is a lack of support programs or language assistance for children adjusting to a new and difficult curriculum, which from grade seven (for children aged around 13) is often taught in English or French, languages in which Syrian students have very little education.

Lebanese secondary schools charge fees and require valid residency. The enrollment rate for Syrians in secondary education is estimated at only 5 percent for 15- to 17-year old children – an age range in which lack of residency and financial pressure to work are particularly prevalent. Human Rights Watch found a near-total lack of inclusive education for children with disabilities in public primary schools.

Donors to educational programs in Lebanon should:

- Call on the authorities to ensure that Lebanon’s school enrollment criteria are clearly communicated to individual school directors and properly implemented,

- Call on the authorities to ensure residency requirements are not imposed as a condition for school enrollment, and waive the residency requirement to enroll in secondary school,

- Work with the Lebanese authorities to ensure that indirect costs, like transport and supplies, are not barriers to primary education,

- Invest in livelihood programs that ease financial barriers to education,

- Earmark funding for teacher training, remedial support programs, secondary education, and inclusive education for children with disabilities.

Jordan

Jordan has opened free “second shifts” at nearly 100 primary schools to accommodate Syrian children in host communities. New schools opened in 2015 in Zaatari, the country’s largest refugee camp. However, as Jordan’s Response Plan for the Syria Crisis (2016-18) notes, “nearly 100,000 Syrian children are missing out formal education,” because their families cannot cover the cost of transportation and education material, or depend on their children to generate income to meet basic needs.

Violence and bullying in school and on the way to school, as well as widespread corporal punishment and perceptions of discrimination from teachers, lead Syrian children to drop out of school. More donor funding for teacher training and to decrease class sizes could help address these problems.

School officials often require Syrian children to produce official Syrian school certificates in order to enroll in secondary school, or at the grade level of their age group in primary school. Yet many Syrian families fled without these documents, and the alternative – for the children to repeat grades they cannot prove they attended – is unappealing. School officials are concerned that children who have missed foundational years will lower the quality of education if they are placed in higher grades, but Jordan could address those concerns by implementing standardized school-placement tests, and working with nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) to expand accelerated learning programs in host communities, not only in camps, that bring out-of-school children up to their grade level.

Because Syrians caught working without work permits, which virtually none has, are liable to arrest and transfer to a refugee camp, a large percentage of Syrian families in host communities depend on their children to work, as children are seen as at less risk of arrest. As a result, children drop out of school to work, including in hazardous conditions. These policies also dissuade Syrian children from pursuing an education, since schooling will not help them on the only available job market for low-paid, unskilled labor. Reportedly due to fears that skilled Syrian workers could compete with Jordanian workers, Jordan does not allow humanitarian NGOs to operate vocational training programs for children and young adults outside of the main refugee camps, where about 83 percent of Syrian refugees live. The International Labour Organization (ILO) has recommended that Jordan give refugees access to work, and that the international community support measures to mitigate negative perceptions and economic impacts amongst host communities.

Jordanian authorities have not permitted Syrians who left the country’s refugee camps after July 2014 to register their non-camp residence with UNHCR, receive humanitarian support, or obtain government-issued identification cards.[22] The policy may prevent thousands of Syrian refugee children who have left Azraq or Zaatari camps since July 2014 from enrolling in public schools, which require Syrians to present such documents.[23]

Donors should call on Jordan to improve its policies affecting Syrian refugees’ access to education by:

- Working with donors to ensure that indirect costs, like transport and supplies, are not barriers to primary education,

- Ensuring humanitarian agencies can operate accelerated learning and vocational training programs for Syrian refugees living outside refugee camps,

- Ensuring that Syrian children whose families lack official documents, including Syrians who arrived after July 2014, are able to enroll in public schools, and

- Committing to working with donors to establish programs granting access to lawful work for Syrian refugees.

Turkey

Turkey, which is hosting more Syrian refugees than any other country, says it has spent billions of dollars on its refugee response. It has implemented positive policy changes to accommodate the protracted nature of the crisis, particularly by issuing a temporary protection regulation in October 2014 that ensured Syrians could remain lawfully in Turkey without official residency permits. Under its temporary protection regime, it has allowed Syrian children to attend public schools free of charge and begun to accredit independent schools that teach a modified Syrian curriculum in Arabic—called “temporary education centers.” In January 2016, Turkey published a regulation that will allow Syrians with temporary protection status to apply for work permits six months after they receive temporary protection status.[24] Enabling Syrians to support themselves should have significant benefits for refugee children’s access to education, since child labor is a major cause of drop-outs and non-enrollment.

However, around 400,000 Syrian children in Turkey are not in school. While giving Syrians lawful access to the public school system was an important step, practical barriers—including a language barrier, lack of information, economic hardship, and bullying of children by other school children—continue to prevent children from taking advantage of that access. Furthermore, some schools are turning away Syrian children who are fully entitled to attend, in direct contravention of the relevant regulations.

The Turkish ministry of education has indicated its commitment to addressing these issues by developing programs to offer language assistance, teacher training, and better oversight to ensure that schools across the country comply with their directives. In addition, it has supported the construction of new temporary education centers and provided avenues for qualified Syrian teachers to be compensated for their work in those centers. But more will need to be done, and urgently, in order to prevent a generation of Syrian children in Turkey from growing up without an education.

Donors should encourage Turkey to maintain its commitment to positive policies and offer the crucial financial and technical support necessary to ensure that all Syrian children are able to attend school. In particular, donors should support efforts to:

- Fairly and rapidly implement the new policy giving Syrian refugees access to work permits in Turkey,

- Implement accelerated Turkish language programs for non-Turkish language proficient students through the public school system,

- Closely monitor and supervise local compliance with national directives related to the education of Syrian children,

- Invest in training for teachers and school personnel tailored to educating non-Turkish-speaking refugees in order to combat discrimination and encourage social inclusion, and

- Disseminate accurate information to Syrian refugees, including those in harder-to-reach areas, regarding the procedures and requirements for school registration.

There is an acute need for participants to meet the goals of this conference through generous donations and by pressuring all parties to the conflict in Syria to protect civilians. Donors should also call on host countries to revise policies, described in this memorandum, that may harm their stability as well as the rights of refugees.

[1] Entries occur at the Rukban and Hadalat border points, north of the Jordanian town of al-Ruweishid.

[2] “Jordan: Syrians Held in Desert Face Crisis, Satellite Imagery Confirms Thousands in Remote Border Zone,” Human Rights Watch news release, December 8, 2015, https://www.hrw.org/news/2015/12/08/jordan-syrians-held-desert-face-crisis.

[3] Khetam Malkawi, “Jordan willing to help third countries absorb ‘border camp’ Syrian refugees — Momani,” Jordan Times, January 11, 2016, http://www.jordantimes.com/news/local/jordan-willing-help-third-countries-absorb-border-camp%E2%80%99-syrian-refugees-%E2%80%94-momani (accessed January 27, 2016).

[4] “Jordan: Syrians Blocked, Stranded in Desert, Satellite Imagery Shows Hundreds in Remote Border Zone,” Human Rights Watch news release, June 3, 2015, https://www.hrw.org/news/2015/06/03/jordan-syrians-blocked-stranded-desert.

[5] “Jordan: Palestinians Escaping Syria Turned Away, Others Vulnerable to Deportation, Living in Fear,” Human Rights Watch news release, August 7, 2014, https://www.hrw.org/news/2014/08/07/jordan-palestinians-escaping-syria-turned-away.

[6] “Jordan: Vulnerable Refugees Forcibly Returned to Syria: Halt Deportations; Investigate Shooting,” Human Rights Watch news release, November 23, 2014, https://www.hrw.org/news/2014/11/23/jordan-vulnerable-refugees-forcibly-returned-syria; “Jordan: Syrians Held in Desert Face Crisis, Satellite Imagery Confirms Thousands in Remote Border Zone,” December 8, 2015.

[7] UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), “Syria Regional Refugee Response: Inter-agency Information Sharing Portal”, undated, http://data.unhcr.org/syrianrefugees/country.php?id=224 (accessed January 27, 2016); Human Rights Watch, Turkey - When I Picture My Future, I See Nothing, November 2015, https://www.hrw.org/node/282910/.

[8] “Turkey: Syrians Pushed Back at the Border: Closures Force Dangerous Crossings with Smugglers,” Human Rights Watch news release, November 11, 2015: https://www.hrw.org/news/2015/11/23/turkey-syrians-pushed-back-border.

[9] “Turkey’s new visa law for Syrians enters into force,” Hurriyet Daily News, January 10, 2016, http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/turkeys-new-visa-law-for-syrians-enters-into-force.aspx?pageID=238&nID=93642&NewsCatID=352 (accessed January 27, 2016).

[10] These are the Cilvegözü/Bab al-Hawa crossing near Reyhanlı, about 30 kilometers east of Antakya, and the Öncüpınar/Bab al-Salama crossing near Kilis, about 50 kilometers southeast of Gaziantep.

[11] Almost 25,000 people, most of them Syrians, fleeing fierce fighting in the border town of Tal Abyad, entered Turkey in mid-June 2015, but only after they forced their way through the closed border fence after Turkish security forces pushed them back with warning shots and water cannons. The group entered through or near the Akçakale border crossing, 50 kilometers south of Urfa.

[12] Most Syrians during this period entered Turkey through mountainous border regions north and southeast of Antakya.

[13] “Russia/Syria: Extensive Recent Use of Cluster Munitions: Indiscriminate Attacks Despite Syria’s Written Guarantees,” Human Rights Watch news release, December 20, 2015, https://www.hrw.org/news/2015/12/20/russia/syria-extensive-recent-use-cluster-munitions.

[14] “Lebanon: Stop Forcible Returns to Syria, Assess Risk of Harm Facing Those Sent Back,” Human Rights Watch news release, January 11, 2016, https://www.hrw.org/news/2016/01/11/lebanon-stop-forcible-returns-syria.

[15] Michel Sleiman, February 7, 2013, https://twitter.com/SleimanMichel/status/299478936423899136 (accessed January 27, 2016); Letter from Human Rights Watch to Lebanese Officials Regarding Deportation of Syrians, August 04, 2012, https://www.hrw.org/news/2012/08/04/letter-lebanese-officials-regarding-deportation-syrians; “Lebanon: Palestinians Barred, Sent to Syria, Reverse Blanket Rejection of Refugees,” Human Rights Watch news release, May 05, 2014, https://www.hrw.org/news/2014/05/05/lebanon-palestinians-barred-sent-syria; “Lebanon: Syrian Forcibly Returned to Syria

Investigate Report of Deportation; Halt Forcible Returns,” Human Rights Watch news release, November 07, 2014, https://www.hrw.org/news/2014/11/07/lebanon-syrian-forcibly-returned-syria.

[16] “Lebanon: Residency Rules Put Syrians at Risk: Year after Adoption, Requirements Heighten Exploitation, Abuse,” Human Rights Watch news release, January 12, 2016, https://www.hrw.org/news/2016/01/12/lebanon-residency-rules-put-syrians-risk.

[17] “Lebanon: Residency Rules Put Syrians at Risk: Year after Adoption, Requirements Heighten Exploitation, Abuse,” January 12, 2016.

[18] Children under 15 can renew for free, but their application is tied to the legal status of the head of household.

[19] Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey are bound by human rights law (the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, or ICESCR, and the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, or CERD) to respect the right to work without discrimination of non-nationals. The ICESCR compliance committee has emphasized that the right to work applies “to everyone including non-nationals, such as refugees, asylum-seekers, stateless persons […] regardless of legal status and documentation.” The CERD compliance committee acknowledges states' right to differentiate between citizens and non-citizens, but says that States should remove obstacles that prevent the enjoyment of economic, social, and cultural rights by non-citizens in the area of employment and to take measures to eliminate discrimination against non-citizens in relation to working conditions and requirements. In summary, these rules mean states can regulate access to employment but should not automatically exclude all asylum seekers and refugees from working. States do not have to give them unfettered access to the labor market, but should make sure they have a meaningful opportunity to engage in wage-earning employment in non-discriminatory conditions.

[20] “Lebanon: Women Refugees from Syria Harassed, Exploited,” Human Rights Watch news release, November 26, 2013, https://www.hrw.org/news/2013/11/26/lebanon-women-refugees-syria-harassed-exploited; and “Lebanon: Residency Rules Put Syrians at Risk: Year after Adoption, Requirements Heighten Exploitation, Abuse,” Human Rights Watch news release, January 12, 2016.

[21] Government of Lebanon and United Nations, “Lebanon Crisis Response Plan 2015-16, Year Two,” December 15, 2015, http://data.unhcr.org/syrianrefugees/download.php?id=10057 (accessed January 27, 2016).

[22] In a positive move, in November 2015, Jordan relaxed requirements for Syrians in host communities to comply with requirements to verify their residences, and reduced costs for them to obtain required health tests.

[23] There were around 607,000 refugees registered with UNHCR in Jordan on July 15, 2014, and around 635,000 on January 22, 2015.

[24] “Karar Sayısı : 2016/8375,” http://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/2016/01/20160115-23.pdf (accessed January 27, 2016).