Summary

Since 2011, violence in Syria has forcibly displaced at least 1.6 million school-age children to other countries in the region. Before the conflict, more than 90 percent of Syrian children attended primary school and 70 percent attended secondary school. By the fall of 2015, despite international support to prevent a “lost generation,” only around 50 percent of Syrian refugee children in the region were enrolled in school.

Host countries and foreign donors are crucial partners if Syrian refugee children are to realize their right to education. But Human Rights Watch’s previous research in Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan has shown that host country policies have created obstacles to their education, including restrictions that exacerbate poverty and add to pressures for children to work or marry rather than go to school. In addition, since local resources are insufficient, Syrian children’s access to education also depends on the effective delivery of adequate international aid, which has often been lacking.

This report tracks donors’ fulfillment of their pledges to support education for Syrian refugees in 2016. It focuses on pledges made at a major conference in February 2016 in London, where donors—the six largest were the European Union, US, Germany, United Kingdom, Norway, and Japan—committed to provide $1.4 billion in funding for education inside Syria and in neighboring countries, and agreed with refugee-hosting countries to enroll all Syrian refugee children, as well as vulnerable children in host communities, in “quality education” by the end of the 2016-2017 school year.

Overall education funding in 2016 exceeded the conference’s target of $1.4 billion, and enrollment has increased since then. However, at least 530,000 Syrian children are still not receiving any education in Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan—the three countries hosting the largest numbers of Syrian refugee children—and donors missed the specific funding targets for Jordan and Lebanon that conference participants endorsed.

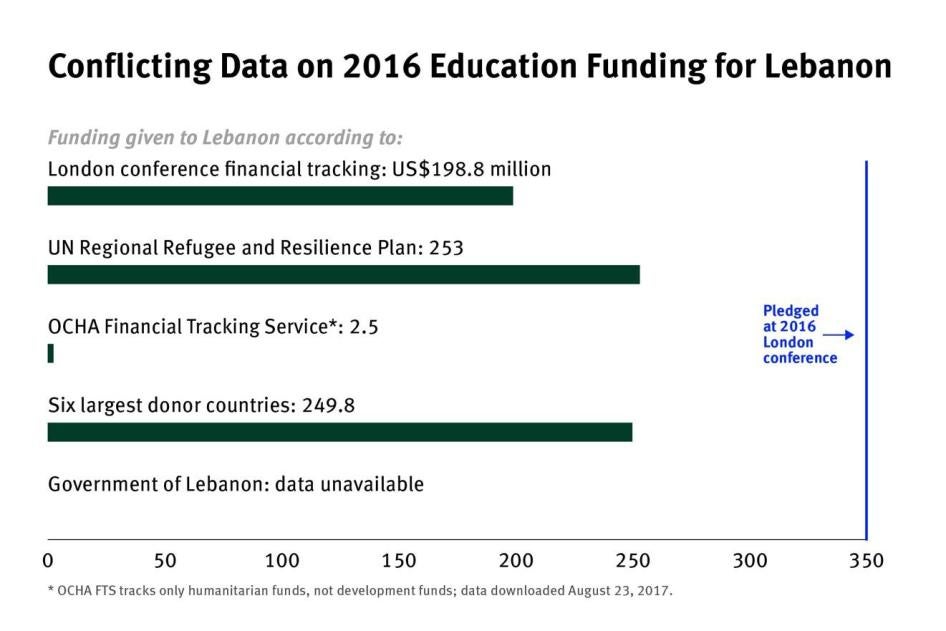

For example, the London conference put Lebanon’s annual education needs at $350 million, yet the United Nations reported that, in 2016, Lebanon received only $253 million for education under a UN-coordinated aid plan—a $97 million shortfall. The six donors reported that in 2016 they gave $223.4 million for education in Lebanon.

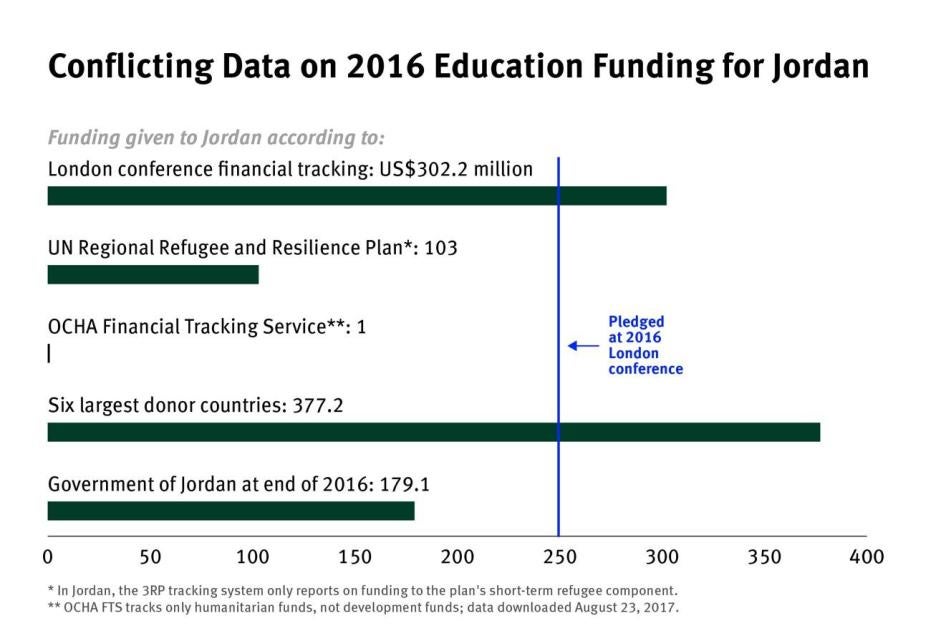

Similarly, Jordan did not receive enough education funding, but different sources offer widely differing accounts of how much it did receive. London conference participants agreed that Jordan needed $1 billion over three years for education, of which Jordan budgeted $249.6 million for 2016. But by the end of the year, Jordan reported that it had received just $179.1 million for education, a $70.5 million shortfall. An update that Jordan published later stated that the total figure was $208.4 million, a $41.2 million shortfall. Yet, according to the six donors, they gave $379.2 million to education in Jordan in 2016.

Of the funding that was delivered, much came late, rather than well before the school year as London conference participants had agreed: as of early September 2016, funding for education in Jordan was still 69 percent short of targets under a UN-coordinated aid plan, and 47 percent short in Lebanon. The failure to deliver aid before the school year limits school systems’ capacity to hire and train teachers, purchase textbooks, and plan student intake, with the result that fewer Syrian children are able to realize their right to education.

Main Problems

In seeking to identify the source and impact of these funding shortfalls, our research revealed several main underlying problems:

- Lack of consistent, detailed, timely reporting by donors, which often made it difficult or impossible to determine how much support individual donors have given to education in each host country, and when. Several donors told Human Rights Watch they had made multi-year commitments to fund education, but the UK is the only donor that has published detailed information about multi-year funding commitments to both the Lebanese and Jordanian governments’ education plans.

- Lack of information about the projects donors are funding, and their timing. Public fund-tracking reports, databases, and other mechanisms often lack enough information to assess whether funding addressed the key obstacles to education for Syrian children, such as a lack of access for secondary-school-age children and children with disabilities, as well as when funds are committed or disbursed. Some donors have counted project funds to be disbursed in future years against their 2016 pledges. Germany, for instance, counted a €15 (US$15.75 at the time) million project that will run to 2019 this way.

- Inconsistent information about school enrollment, which makes it difficult to assess progress. Data are often based on different criteria, were collected at different times, or may account only for enrollment at the beginning of the school year rather than continued attendance. In Jordan, the government reported substantially increased enrollment figures after the London conference, but then improved its enrollment-tracking system, revealing that fewer Syrians went to school than previously estimated for the 2015-2016 school year.

- Inconsistent education targets and goals set by donors and host countries. The London conference co-hosts announced that all participants had agreed to enroll all Syrian children by 2017, but the Lebanese government announced a 5-year educational plan at the conference that will still leave more than 156,000 Syrian children out of public schools by 2021.

Ways Forward

More detailed, comprehensive information on education aid is needed to assess whether donors have met their own pledges and provided aid in a timely way, and whether the activities being funded address key obstacles that are hampering the realization of the right to education for hundreds of thousands of Syrian refugee children. Donors, implementing agencies, and host governments need to know what programs are being funded in order to coordinate their efforts effectively and avoid gaps or overlaps in aid.

Greater transparency could help to show why enrollment goals are being missed, identify the responsible parties, and pressure them to improve. It could pinpoint the extent to which host country policies, as opposed to insufficient donor funding, are keeping children out of school.

This report does not call on donors to increase or earmark funding for education if doing so would shift funding from other humanitarian needs, or tie the hands of implementing agencies or host country governments that may be best-placed to assess where resources are needed. Also, more funding may not help if host countries’ policies undermine children’s access to school. In some provinces in Turkey, for instance, Syrian refugees can face indefinite delays getting the identification card that children need to enroll in public schools. Lebanon has issued virtually no work permits to Syrian refugees, and many refugee families cannot afford school-related costs.

But in cases where donors have pledged to support educational goals, failure to meet those pledges may undermine the budgeting and planning of education programs, harming the children whose access to school hangs in the balance. Donors should meet their own commitments to give the amounts pledged, and ensure their funding is more transparent, targeted, and timely.

Donors have long acknowledged the need to improve aid transparency. In 2011, donors including those profiled in this report, pledged to increase transparency for development aid by the end of 2015; in May 2016, they committed to transparency for humanitarian funding by 2018. Specifically, donors pledged to use a common standard to publish comparable, timely, detailed, and comprehensive aid information. But as of February 2017, only Germany and the United Kingdom had accordingly published figures on 2016 aid for education in Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey that roughly matched the sums which the donors themselves reported to Human Rights Watch.

To prevent a lost generation of Syrian children and help realize their right to education, donors and host countries should improve transparency and accountability by:

- Publishing up-to-date, detailed information on all funding committed, and received, to support education for Syrian and vulnerable host community children in Syria and neighboring countries, including on multi-annual commitments and commitment and disbursal dates; and

- Renewing efforts to identify and overcome barriers that have thwarted universal enrollment for Syrian refugee children, revising policies accordingly, and publishing data on school enrollment and attendance that are comparable, up-to-date, disaggregated by age and gender, and account for dropouts.

Recommendations

To Donors

- Make multi-annual, country-specific funding pledges for education, to enable host countries to realize the education aims endorsed at the London Conference.

- Act on commitments to increase aid transparency by publishing timely and comprehensive data on funding for education in Syria and neighboring countries in the International Aid Transparency Initiative Standard.

To the London Conference Co-Hosts

- Provide a breakdown of education funds for Syria and the region by donor and recipient country in future reports on fulfillment of aid pledges and publish the underlying data.

To the European Union’s Directorates-General ECHO and NEAR and the European External Action Service

- Include detailed information on all aid, including multi-annual commitments, for education in Syria and the region in the public fund-tracking database (EDRIS) maintained by the Directorate-General ECHO or in the EU Aid Explorer.

To the EU’s Directorate-General NEAR

- Publish data on all funded projects in the International Aid Transparency Initiative Standard and include information on contracted amounts as “commitments.”

- Publish the same level of detailed information on projects funded by the Madad Fund as it is done for the Facility for Refugees in Turkey.

To the United States State Department and US Agency for International Development

- Ensure that the Foreign Aid Explorer and ForeignAssistance.gov contain correct and detailed information on all aid for education in Syria and neighboring countries, including on multi-annual commitments.

- Publish comprehensive data on aid in the International Aid Transparency Initiative Standard; ensure that the data are correctly formatted so that education projects can be identified by querying the International Aid Transparency Initiative Registry.

To the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development

- Ensure that that project data published in the International Aid Transparency Standard is updated, classifies all projects supporting education in Syria and neighboring countries as “education,” and includes commitment dates.

- Ensure that the fund-tracking portal “Projektdaten-Visualisierung” displays information on commitments and disbursements, a fine-grained sector classification, and a sector breakdown between project components.

To the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development

- Ensure that data published in the International Aid Transparency Initiative Standard correctly list education components for all grants.

To the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation

- Ensure that commitment dates of all education grants to Syria and neighboring countries are included in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ Grants Portal, to show the amount of education funds made available before the beginning of the school year.

- Publish comprehensive and timely information on aid in the International Aid Transparency Initiative Standard.

To the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan

- Publish comprehensive, detailed, and timely information on all aid for education in Syria and its neighboring countries in the International Aid Transparency Initiative Standard, including on multi-annual commitments.

To the International Aid Transparency Initiative

- Ensure that the International Aid Transparency Initiative Standard includes a detailed sector classification in data on humanitarian aid. The classification should be in accordance with the Inter-Agency Standing Committee’s standard sectors.

To Host Country Governments

- Cooperate with the United Nations to regularly publish comparable, up-to-date attendance data for Syrian school-age children that account for dropouts during the school year. Break the figures down between participation in formal, non-formal, and informal education; and enrollment in pre-primary, primary, lower- and higher-secondary education.

- Make work permits more accessible to reduce poverty-related barriers to education by abolishing requirements for sponsorship by an employer.

- In cooperation with donors:

- Set and meet higher targets to increase access to secondary education and vocational training for refugee and host community children,

- Set and meet higher targets to increase access to education for refugee and host country children with disabilities,

- Increase access to quality, non-formal education for children who have been out of school for years or are unable to access formal education.

- Enforce bans on corporal punishment at school, hold teachers accountable for corporal punishment of students, and ensure that allegations of corporal punishment, harassment, or discrimination are investigated and redressed.

To the Jordanian and Lebanese Governments

- Allow qualified Syrian teachers to teach in accredited programs.

To the Lebanese and Turkish Governments

- Publish updated, detailed information on all international aid received in response to the Syria crisis, and indicate the amount received, the date, recipient, and use or project.

- In cooperation with donors, increase access to programs offering language support and accelerated language learning for Syrian children.

To the Jordanian Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation

- Include a breakdown by donor of education funding under the Jordan Response Plan in published funding updates.

- Include budget aid and funding for projects implemented by ministries that are received under the Jordan Response Plan in the Jordan Response Information System for the Syria Crisis project search.

To the Lebanese Government

- Extend the waiver of residency fees to all refugees in the country, and ensure that it is consistently applied by all General Security offices.

- In cooperation with donors, implement schemes to create jobs for Lebanese and Syrians as announced at the London conference.

To the Turkish Government

- Establish transparent targets for international aid necessary to achieve universal school enrollment of Syrian and vulnerable host community children in Turkey.

- Clear the backlog of identification card (kimlik) applications, and make sure that all refugee children can enroll as guest students while awaiting their documentation.

Methodology

This report is based on analysis of public reporting by United Nations agencies; the governments of Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan; and the six largest donors to education in the Syria context: the European Union, United States, Germany, United Kingdom, Norway and Japan. Human Rights Watch reviewed reports on the fulfillment of funding pledges made at the London conference; UN and Jordanian mechanisms to track funds given under the UN-coordinated 3RP regional aid plan for the Syria crisis; a global financial tracking database maintained by the UN’s humanitarian coordination agency (OCHA); data published in the International Aid Transparency Initiative Standard; and public databases and other figures.

Human Rights Watch also emailed officials responsible for development and humanitarian assistance from the EU, US, Germany, UK, Norway, and Japan, and requested information on the amount of 2016 aid made available for education in Syria and of Syrian and vulnerable host community children in the region. We also requested information on the projects being supported. All donors provided replies. We shared our preliminary findings in meetings with EU and German officials and in letters to other donor countries; this report reflects their responses.

Human Rights Watch requested and received information on 2016 donor funding from the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF) offices in Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey; the UN Educational, Social and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in Lebanon and Jordan; the Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA) in Lebanon, and International Organization for Migration (IOM) in Turkey.

The London Conference did not specify if 2016 funding pledges referred to funds to be committed, contracted, or disbursed in that year. Some donors reported disbursed funds, others reported contracted or committed funds, or did not specify. Where possible, this report indicates if figures refer to commitments, contracted sums, or disbursements.

All currencies are converted into US dollars at the rates used by the London conference co-hosts to convert funding pledges into US dollars: $1.05/€1; $1.43/£1; $0.12/NOK 1.[1]

I. Background

Syrian Refugee Children's Right to Education

Under the international legal principles codified in the conventions on children’s rights; on economic, social and cultural rights; and on the elimination of discrimination, Syrian refugee children have the right to free primary education and generally accessible secondary education without discrimination.

Countries hosting Syrian refugees are party to a number of international treaties that provide that primary education shall be “compulsory and available free to all” and that secondary education “shall be made generally available and accessible to all.”[2] For children who have not received or completed their primary education, “[f]undamental education shall be encouraged or intensified.”[3] Governments also have an obligation to “[t]ake measures to encourage regular attendance at schools and the reduction of drop-out rates.”[4]

International law prohibits discrimination on grounds such as religion, ethnicity, social origin, or other status.[5] A government that fails to provide a significant number of individuals “the most basic forms of education is, prima facie, failing to discharge its obligations” under the right to education.[6]

The Convention on the Rights of the Child provides that “with regard to economic, social and cultural rights,” which include the right to education, “States Parties shall undertake such measures to the maximum extent of their available resources and, where needed, within the framework of international co-operation.”[7]

Enrollment and Out-of-School Numbers

Since 2011, the Syria conflict has forcibly displaced 1.6 million school-age children from Syria to Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey.[8]

Before the conflict, more than 90 percent of children in Syria attended primary school and 70 percent attended secondary school.[9] In contrast, during the 2015-2016 school year, nearly 50 percent of Syrian refugee children in the region were not receiving any education. At that time, in Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey, at least 715,000 of 1.46 million Syrian refugee children ages 5 to 17 were deprived of their right to education.[10]

At the February 2016 London Conference, donors and host countries committed to enroll all Syrian refugee children ages 5 to 17, as well as vulnerable children in host communities, into formal or non-formal “quality education” by the end of the 2016-2017 school year. No country achieved this goal.[11] As of December 2016, at least 530,000 out of 1.48 million Syrian refugee children were not receiving any education.

Information about enrollment is inconsistent, however, and it is consequently difficult to assess progress towards universal enrollment, as is discussed in chapter 3.

London Conference on Syria

At a conference in London in February 2016, donors and host countries agreed on $12 billion in support to Syria and the region, “the largest amount ever raised in a single day for a humanitarian crisis,” according to the co-hosts. [12] Amongst other pledges, donors committed to provide $1.4 billion in funding for education inside Syria and in neighboring countries annually; of this total, about $250 million should have been delivered to Jordan and $350 million to Lebanon in 2016. No specific target was endorsed for Turkey.

Main Aid-Tracking Mechanisms

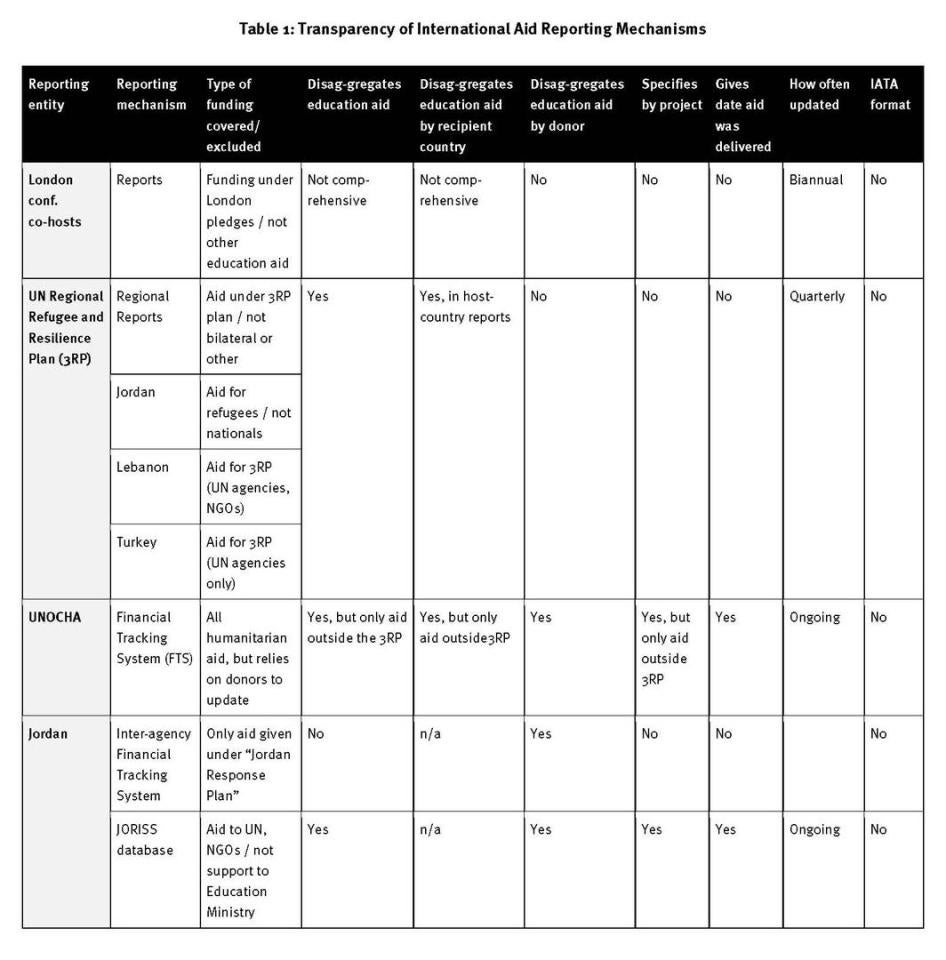

Mechanisms to track the delivery of aid, including for education, include reports and databases published by UN agencies that coordinate international aid in response to the Syria crisis, the London Conference co-hosts, recipient governments, and donors. The shortcomings of the information available from these sources are discussed in chapter 2.

II. Budgeted Education Needs Not Met, Aid Provided Late

Donors over-fulfilled the overall funding needs for education assessed at the London conference. Participants noted that at least $1.4 billion a year from pledges was needed for education.[13] The six largest donors told Human Rights Watch that, in 2016, they had made available education funding of more than $1.5 billion for Syria and the region. But reports on the amount of funding given and received differed significantly, depending on the source. Lebanon and Jordan nonetheless received substantially less education funding than donors had agreed to provide, based on budgeted needs.

London Conference participants recognized that host countries need to receive funding well before the beginning of the school year to hire and train teachers, print textbooks, and prepare classrooms.[14] But by the start of the 2016-2017 school year, funding for education was still 45 percent short of funding targets under the aid plan.[15]

London Conference participants also called for multi-year, predictable funding commitments, to allow host countries to plan student intake, but there is little public information on respective commitments.[16] The German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development for example informed Human Rights Watch that all its 2016 education funding commitments in response to the Syria crisis are part of multi-annual commitments, but this was not reflected in the public information reviewed for this report.[17]

A lack of transparent and consistent reporting means that it is often impossible to determine how much money a host country has received for education, or how much it can expect to receive in coming years. These circumstances impede coordination between donors, host countries and other actors like United Nations agencies and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and lead to short-term education planning. As a result, the efficiency and quality of education programs are limited, and more children are denied their right to education.

Jordan

The London Conference agreed to provide Jordan $1 billion over three years for universal education for refugees and vulnerable Jordanian children.[18] Of this Jordan budgeted $249.6 million for 2016.[19] But Jordan, the London Conference co-hosts, and individual donors provided substantially different information as to the fulfillment of these pledges.

According to the Jordanian government, as of January 3, 2017, donors had delivered only $179.1 million in education funding for 2016 under the Jordan Response Plan, leaving an education budget shortfall of $70.5 million.[20] In April 2017, Jordan stated that the total 2016 education funding received was $208.4 million, a $41.2 million shortfall.[21]

Of the funding that was received, more than $100 million was delivered only after the school year began.[22] Jordan said that by September 6, 2016, it had received only $78.7 million in education funding underpinned by a grant agreement or firm commitment letter.[23] The London Conference co-hosts, however, reported that, as of September, participants had already provided $245.1 million,[24] and $302.2 million by the end of 2016.[25]

The six major donors provided still different figures. According to these donors, they had provided Jordan with education funding of $377.2 million in 2016.[26] Some donors reported multi-year total sums towards the fulfillment of their pledge for 2016, which may explain this discrepancy. This practice obscures whether or not annual funding needs have been met. The United States’ figure in particular appears too high, which may in part be because the US reported funding given during the US fiscal year, not the 2016 calendar year (see analysis of US funding below).

In other cases, donors seem to have underreported their own contributions. According to information that European Union officials provided to Human Rights Watch, the EU had provided only $29.6 million (€28.2 million) for education in Jordan in 2016, but Jordan reported that it received $51.4 million (€49 million).[27]

Lebanon

The London Conference endorsed a Lebanese estimate of costs for education at $350 million per year over five years, as part of an educational plan called Reaching All Children with Education II (RACE II).[28] The UN-coordinated Regional Refugee and Resilience Plan (3RP) for the Syria conflict requested $388.2 million for education in Lebanon in 2016, which includes RACE II requirements.[29]

Available information from the UN-coordinated 3RP aid plan indicates that that there was a $180.9 million shortfall for education funding in Lebanon at the start of the 2016 school year.[30] By the end of 2016, a $135 million gap remained for the education sector.[31]

The London Conference co-hosts reported different figures. As of September 2016, coinciding with the beginning of the school year, conference participants had provided $112.4 million for education in Lebanon,[32] and $198.8 million by the end of 2016.[33]

The six largest donors said, however, that they had given Lebanon $249.8 million in education funding by the end of 2016.[34]

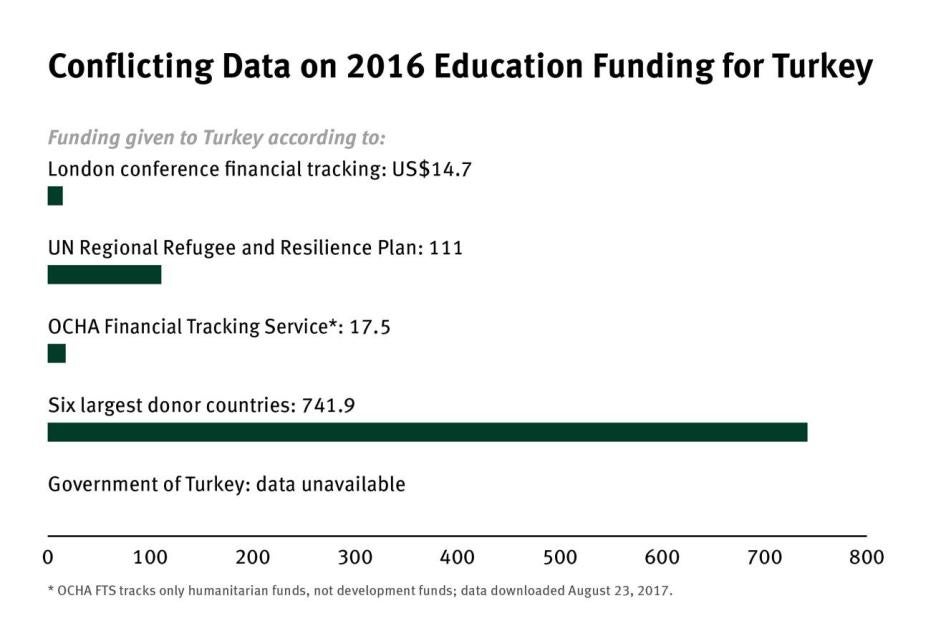

Turkey

The London Conference did not endorse a specific funding target for education of Syrian and vulnerable host community children in Turkey, but the Turkish government assessed the cost of its three-year strategy to achieve universal schooling for Syrian children at $2.7 billion, including $1.17 billion in 2016.[35]

UN aid appeals for Turkey were low relative to Jordan and Lebanon, which host fewer refugees, but were nonetheless underfunded. UN agencies appealed for $137 million to support refugee education in Turkey in 2016 under the 3RP aid plan.[36] At year’s end, $111 million had been received under the 3RP, leaving a gap of $26 million.[37]

The data about the amount of aid available at the beginning of the 2016-2017 school year is incomplete and contradictory. As of September 15, 2016 UN agencies reported aid of $46 million for education in Turkey under the 3RP aid plan, but that number had not been updated since May.[38] The London Conference co-hosts reported that as of September 2016, participants had provided $21.9 million for education in Turkey; but in a second report from February 2017, that number was corrected downward to $14.7 million.[39]

The EU, Germany, Japan, and Norway reported that they had provided $741.9 million in education funding by the end of 2016.[40] The US did not indicate the amount of its aid to Turkey that supports education, and the United Kingdom did not report education aid to Turkey.[41]

III. Lack of Transparency in Education Aid Reporting

Public reporting about the amount, timing, and activities carried out with education aid under the London funding pledges is needed to assess whether donors have met their own pledges, and whether the activities being funded address key obstacles to education. If donors, implementing agencies, and host governments lack information as to which programs are being funded, and when, it will be extremely difficult for them to coordinate efforts and avoid gaps or overlaps in aid. Clarity about aid can help pinpoint the reasons why, despite donor support, hundreds of thousands of Syrian children still lack access to education, and focus pressure on responsible parties to fix problems.

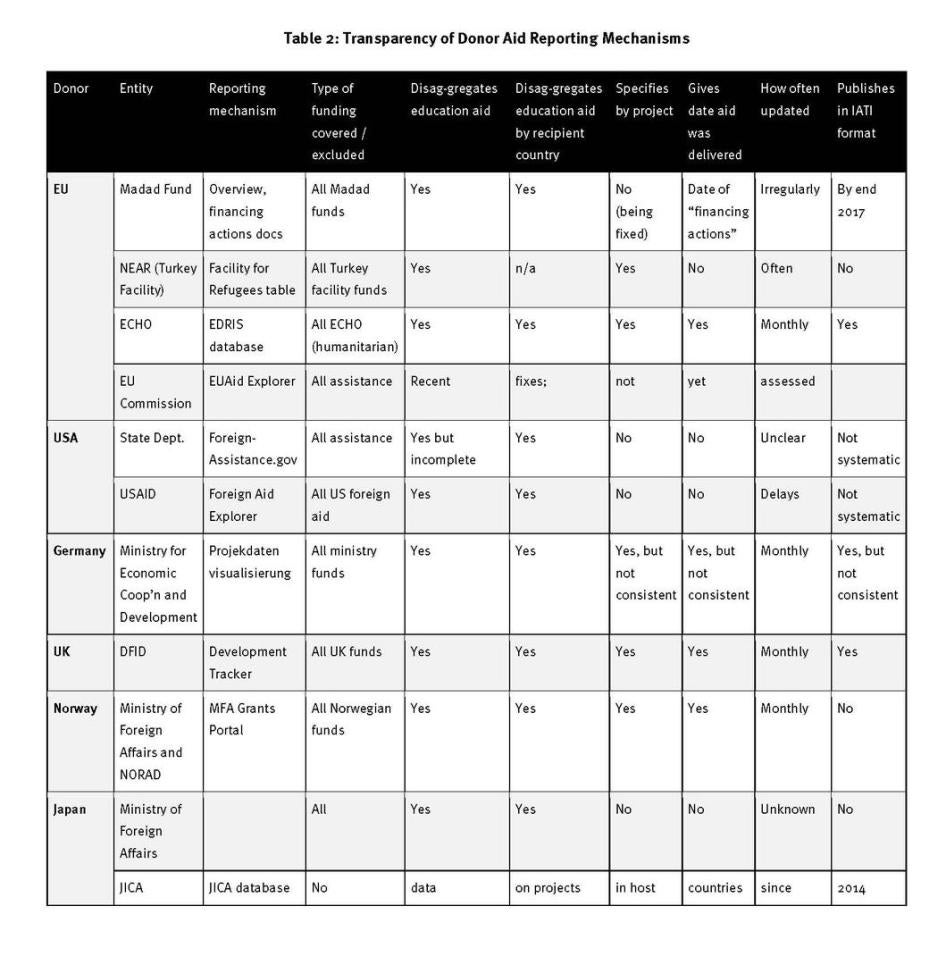

Current public aid-tracking mechanisms, analyzed below, are inadequate. It is often impossible to determine how much funding a particular donor has given, when, and if it addressed key barriers to education (see Table 1). Available data are frequently difficult to compare to different years, or to different countries, and different sources provide apparently contradictory data. Donors have been pledging for years to improve and standardize their reporting of aid. Unless they do so, it will be impossible to know if they are living up to their promises to Syrian children.

London Conference Financial Tracking

The London Conference’s co-hosts—the United Kingdom, Germany, Kuwait, Norway, and the United Nations—reported in February 2017 that participants had committed and disbursed $7.955 billion in overall humanitarian support for Syria and the region in 2016, over-fulfilling the $6 billion funding target. Further reports on pledge fulfillment are planned for 2017, but none had been published as of July 20, 2017.[42]

The co-hosts’ reports are a positive step to create accountability for the delivery of the London pledges. But while they do indicate funding for different sectors, including education, they do not break down funding by donor, which makes it impossible to identify sums made available by individual conference participants. Human Rights Watch requested this information from the UK Department for International Development (DFID), which commissioned the reports, but DFID declined because it did not have conference participants’ consent.[43]

UN Regional Refugee and Resilience Plan (3RP) Financial Tracking

The UN’s Inter-agency Financial Tracking System reports on funds for education for refugee children and children from host communities in Jordan, Lebanon, Turkey, Egypt, and Iraq received by nongovernmental groups and UN agencies under the UN-coordinated 3RP regional aid plan for the Syria crisis on a quarterly basis.[44] It does not account for aid to the governments of recipient countries under the aid plan.

The system breaks data down by receiving country, but not by donor and project.[45]

Although the London Conference funding aims were aligned with the 3RP,[46] conference participants may have made funds for education available outside the plan.

The tracking system can indicate whether funding targets for educating Syrian and vulnerable host community children have been met, but is insufficiently detailed to determine whether donors have met their London Conference pledges.

The tracking system reported on figures for overall education funding under the 3RP as of September 30, 2016.[47] The numbers it presented for Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey were however compiled on different dates, and based on different criteria.[48]

In Jordan, the tracking system only reports on funding to refugee education programs—68 percent of total funding requirements—but not funding to benefit longer-term educational needs of refugee children and vulnerable children in host communities. The Jordan update for the third quarter of 2016 was up-to-date as of September 30.[49]

For Lebanon, the tracking system included funds received by UN agencies and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) as of August 31, 2016.[50]

For Turkey, data only address funding to UN agencies; funding disbursed via NGOs is not accounted for, as these did not participate in the 2016 aid plan. UNHCR released an update on September 15, but the figures had not been updated since May.[51] The overall figures for the 3RP thus only very roughly indicate how much funding was available for education by the beginning of the school year that starts in September 2017.

UN OCHA Financial Tracking Service

The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) operates a public online database, called the Financial Tracking Service, that aims to track all humanitarian funding worldwide and breaks the data down by donor and project.[52] It reports on donor funding to projects in Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan, including those in and out of the UN-coordinated regional aid plan 3RP.[53] However, it does not report which projects under the 3RP address education; such a breakdown is provided only for projects outside the 3RP.

Because the database relies on voluntary reporting by donors and recipients, the detail, reliability, and comprehensiveness of entries vary greatly. Norway, for instance, appears to report for every contribution to the regional aid plan if it supports an education project, but most other donors do not do so systematically.[54]

The European Union channels large parts of its aid to Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan via its Regional Trust Fund in Response to the Syria Crisis (Madad Fund), but does not report this funding to the database, possibly because the fund “focuses on non-humanitarian priority needs” of host communities and Syrian refugees.[55] The Directorate-General for Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection of the European Commission (ECHO), which is in charge of humanitarian affairs, by contrast, automatically synchronizes a database with detailed information on all projects it funds with the Financial Tracking Service.[56]

Jordan Response Plan Financial Tracking

The Jordanian Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation, uniquely among host countries, published regular updates on all funding under the Jordan Response Plan (the local chapter of the 3RP aid plan) that was underpinned by a firm commitment letter or grant agreement for disbursal in 2016.[57] The updates break down overall funding by donor, but not for specific sectors such as education.

The government also maintains an online database, the Jordan Response Information System for the Syria Crisis (JORISS), with detailed funding information on projects implemented under the Jordan Response Plan by nongovernmental groups and by some participating UN agencies, and which is broken down by donor. The database does not, however, include projects implemented by Jordanian ministries, including the education ministry, or direct support to the education ministry’s budget.[58]

The Jordanian government reported 2016 education funding of $179 million as of January 3, 2017 against a funding target of $249.6 million. It reported education funding of only $50.4 million to the aid plan’s component that is covered by the Inter-agency Financial Tracking System for Jordan.[59] The discrepancy vis-a-vis the $103 million reported for this component by the Inter-agency Financial Tracking System as of December 31, 2016, may arise because some UN agencies do not report to the Jordanian government how much of their funds finance specific sectors such as education, or because the UN figures include funds committed in 2016 that will only be disbursed in future years.[60]

The strength of the financial tracking under the Jordan Response Plan is that it only includes funds actually disbursed, and not all funds committed, in a given year, which allows an assessment of whether funding needs in a specific year have been met.

International Aid Transparency Initiative

All donors examined in this report agreed to publish data on humanitarian and development aid using a common standard developed by the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI) by 2015.[61] The IATI format allows actors to publish comparable, timely, detailed, and comprehensive information about aid flows, greatly increasing transparency.[62] However, as of February 17, 2017, only the UK and Germany had published figures on 2016 education funding to Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey in IATI format which roughly corresponded to the figures that these donors reported to Human Rights Watch upon request.[63]

Although it offers the potential for increased transparency, the IATI standard relies on a sector classification developed for development aid. Humanitarian funds are reported under the sector “emergency response,” and are not broken down further.[64] This makes it impossible to assess the extent to which humanitarian aid supports specific sectors such as education.

Individual Donor Financial Tracking

All the analyzed donors maintain a public fund-tracking database, but only the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ Grants Portal reliably shows how much Norway gave for education of refugee children and vulnerable children in Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey during 2016 as well as the specific projects that were funded.[65]

The figures we use in this report have limitations. Donors may have underreported the amount of their funding that was ultimately used for education if they gave support to UN agencies or other implementing partners that was not earmarked for education activities, but was used for education. Non-earmarking of funds can allow implementing partners to assess and flexibly respond to needs that may change over time, but the funds should be tracked after disbursal. The Jordanian government’s JORISS database allows this. On the other hand, donors may have overstated funding for children’s education if they included vocational programs or higher education for adults. The prospect of further education can be an important incentive not to drop out of school for children and increases economic opportunities for adults, but funding to these programs should be tracked separately.

European Union

The EU contracted to support education in Syria and the region in 2016 through its humanitarian arm, the Directorate-General ECHO, and through the Directorate-General for Neighbourhood and Enlargement Negotiations (NEAR) that is in charge of affairs concerning the EU’s neighboring countries.[66]

With regard to transparency, ECHO is one of the leaders among the donors we assessed. It maintains a public database with detailed information on all projects it funds; the database breaks individual projects down by their different components, and is automatically synchronized with the UN OCHA’s Financial Tracking Service.[67] When Human Rights Watch examined the ECHO database in October 2016 it did not break down humanitarian aid to education, apparently due to a programming error; we notified ECHO which promptly corrected the problem.

Other EU funds that support Syria and the region are not reported to the Financial Tracking Service, presumably because they are not considered humanitarian assistance.[68] Important channels of delivery for EU funding are the EU Facility for Refugees in Turkey and the Regional Trust Fund in Response to the Syria Crisis (Madad Fund), both administered by NEAR.[69] The Facility publishes a regularly updated table with information on all funded projects.[70] The Madad Fund, however, only publishes an overview of so-called financing actions, and documents that detail the sums allocated to these actions as well as their aims and planned implementing partners.[71] Funds allocated to financing actions need to be contracted to implementing partners before disbursement, but no detailed information on contracted projects is publicly available. This makes it impossible to get a detailed overview of the education activities funded by the Madad Fund.

The European External Action Service in Jordan informed Human Rights Watch that it also provides multi-annual funding through budget support to the Jordanian education ministry.[72]

Upon request by Human Rights Watch, ECHO and NEAR collected information on all education funds they contracted in 2016 to Syria and the region. The process took more than two months to complete.[73] When we presented our preliminary findings based on these figures to EU officials, they explained that the numbers previously shared did not correctly reflect all EU aid and provided corrected figures.[74] These experiences indicate that it is difficult even for EU officials to get a complete picture of EU aid made available for education under the EU’s London Conference pledge.

ECHO provided a detailed breakdown of its own 2016 funding for education under the EU’s London pledge. In some instances, ECHO’s fund-tracking database displayed education components for ECHO projects that were smaller than those reported for these projects to Human Rights Watch by ECHO.[75]

A substantial part of the EU’s aid for education of refugees and contracted by NEAR is financed by EU member states, not the EU. It is not clear how this aid can legitimately be counted towards the EU’s pledge concerning funds from the EU budget.[76] NEAR and ECHO told Human Rights Watch that the IATI format permits reporting, as EU funding, funds from instruments that pool money from both the EU budget and from member states.[77]

The EU Commission also maintains the EU Aid Explorer, an aid-tracking portal that aims to include information on all development and humanitarian aid by the EU and its member states.[78] As of early 2017, information available from the portal did not reflect what ECHO and NEAR said they had funded. As of April 6, 2017, browsing the portal for ECHO-financed education projects in Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey did not yield any results. A search for EU development projects that supported education in these countries in 2016 yielded only four results, and none of these projects began in 2016. . ECHO and NEAR informed Human Rights Watch in September 2017 that the platform had been improved and was now reporting on education projects.[79] As of September 8, the portal listed 16 development projects for education funded by the EU Commission in Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey, and 5 education projects funded by ECHO in Turkey, for 2016.[80]

ECHO publishes monthly updated data on all funded projects in the IATI format.[81] As of February 17, 2017, the data included information on all projects with education components that ECHO had reported to Human Rights Watch.[82] However, all projects were classified as “emergency response,” and as a result, education projects could not be identified by browsing the IATI data. This is due to a limitation of the IATI standard that does not allow breaking down humanitarian funds by sector.[83]ECHO and NEAR informed Human Rights Watch in September 2017 that changes in the IATI format would soon allow a more detailed breakdown in line with UN OCHA cluster sector categories for humanitarian aid such as “education in emergencies.”[84]

NEAR publishes updated data on funded projects in IATI format every month.[85] The data on 2016 education projects published as of February 17, 2017, did however not correspond to the figures reported as contracted by NEAR to Human Rights Watch. The IATI data only details disbursements and expenses (“spend”), but not contracted amounts as “commitments.” The 2016 spend for education in Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey was $212.6 million (€202.5 million) and commitments were negative, as opposed to the $712.4 million (€711.9 million) of education funds that NEAR reported as contracted in 2016 to Human Rights Watch.[86]NEAR informed Human Rights Watch in September 2017 that all funding by the Madad Fund would be systematically reported in IATI format in the near future and that the data will distinguish between “spend” and “commitments”.[87]

United States

The US and Norway are the only donors examined in this report that made a funding pledge specifically for education at the London Conference. But the US’ reporting practices do not allow an assessment of whether it fulfilled its 2016 pledge.

In response to questions from Human Rights Watch about education funding under the London Conference pledge for 2016, made in February of that year, the US State Department reported figures for the 2016 US Fiscal Year, which runs from October 1, 2015 to September 30, 2016.[88] During that time, the US provided humanitarian aid of $1.4 billion to Syria and the region; some of that funding supported education, but the State Department did not provide information on the amount, or on concrete projects funded, pointing out that it includes non-earmarked funds that may be used for education. [89] In addition, the US Agency for International Development (USAID) funded education and youth programs in Jordan and Lebanon.[90]

The US maintains two public databases with information on all US foreign aid, the USAID Foreign Aid Explorer, and ForeignAssistance.gov, which is run by the US State Department.[91] Human Rights Watch used the USAID Foreign Aid Explorer to the extent possible.[92] As of July 24, 2017, the database listed 22 funded projects (“activities”) under Basic Education, including $30 million for school expansion contracts, $14 million for an early grade reading and math project, and $13 million for furnishing and equipping schools, but no commitment or disbursement dates are listed and no further documents are provided. In many other cases, the project descriptions are very broad, such as “basic education.” As of July 24, Foreignassistance.gov listed 58 projects under Basic Education and 2 projects under Higher Education in Jordan for fiscal year 2016, and allowed users to download a file with all funding to Jordan, including disbursement dates.

There is a substantial discrepancy regarding Jordan. As of July 14, 2017, the USAID Foreign Aid Explorer reported $82 million in educational projects in Jordan for the 2016 US fiscal year, and not $248 million as reported by the State Department.[93] Reporting for the 2016 fiscal year had not been finalized, but the database figure for education funding to Lebanon, by contrast, matched the figure provided to Human Rights Watch.[94] Information from the Jordan Response Information System for the Syria Crisis accounted for $13 million in US aid for education in Jordan in the 2016 calendar year.[95]

The US aimed to publish quarterly project data on all its development funding in IATI format by the end of 2015.[96] Human Rights Watch reviewed the IATI data published as of February 17, 2017, for “spend” (disbursements and expenses) on education projects in Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey during the 2016 US Fiscal Year that started on October 1, 2015. The data included information on US spend of $13.8 million on education projects in Jordan, $26.4 million in Lebanon, and $36,000 in Turkey, more than $200 million less than indicated by the State Department. [97] We checked for funding commitments made to these projects in the 2016 US Fiscal Year, but information on these appeared not to be systematically included in the published IATI data;[98] we also tried to extract more detailed data on US education funding to these countries from the IATI registry, but queries yielded no results, possibly due to formatting errors in the data.[99]

Germany

The German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development is transparent about aid for education of refugee and vulnerable host community children in Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey, but there is room for improvement. Human Rights Watch obtained a detailed list of 2016 funding commitments to education projects funded by the ministry under the German pledge, which was up-to-date as of December 12, 2016.[100]

The ministry publishes data on projects it funds in the IATI format; it plans to update this data monthly, but had not done so in early 2017.[101] As of February 2017, publicly-reported 2016 funding included $151.7 million (€ 144.5 million) of 2016 commitments to education projects in Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey, but the ministry had reported commitments of $184 million (€ 175.3 million) to Human Rights Watch in December 2016.[102] The discrepancy could be because the ministry publishes new data with a delay of three months.[103]

In many cases, the projects were not tagged as “education” in the IATI data, making it impossible to find them by browsing the data for education projects.[104] As well, commitment dates were often not included in the data.[105] For one project, the IATI data showed a €21 million ($22 million) commitment, but the ministry reported a €10 million commitment to Human Rights Watch.[106]

The ministry operates a public fund-tracking portal, in German, based on its IATI data. The portal displays overall project budgets and the sector category (such as education), but provides no information on commitments, disbursements, the fine-grained sector classification that IATI allows for (such as primary education), or a sector breakdown between project components.[107]

On the one hand, some German-funded projects that are not classified as educational are likely to support children’s access to school, such as allowing adult refugees to improve their skills and find work, and hence earn enough income to afford to send their children to school. For example, Germany pledged €200 million for the Partnership for Prospects that aims at creating 500,000 jobs in Syria’s neighboring countries by 2017.[108] On the other hand, as with several donors, Germany appears to have over-counted the sum it reported for 2016, by including funding committed for future years of multi-annual projects.[109]

The ministry informed Human Rights Watch that all funded education projects in Syria and its neighboring countries are multi-annual, but this was not reflected in the public information reviewed for this report. As of August 25, 2017, the sum of contracted education funds for the Syria crisis – including both refugee-hosting countries as well as inside Syria – had increased to US $ 257.1 million (€244.9 million) in 2016. Of this, $145.3 million (€138.4 million) were disbursed in the same year and $111.9 million (€106.6 million) are to be disbursed over the following years.[110]

United Kingdom

The UK publishes transparent information about the disbursal of funds for education in Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey. Upon request by Human Rights Watch, DFID provided detailed information on funds disbursed under the UK’s London pledge for 2016.[111]

DFID publishes data on projects funded by the UK in IATI format on the 15th working day of each month.[112] As of February 17, 2017, the IATI data included information on 2016 disbursements to all projects for which DFID had reported disbursements for education to Human Rights Watch, as well as multi-annual commitments.[113] The data however only classified disbursements of $71.2 million (£49.8 million) to projects in Jordan and Lebanon as “education,” instead of the $81.9 million (£57.3 million) that DFID had reported to Human Rights Watch. In one case, DFID had reported disbursals of $18 million (£12.6 million), but the IATI data only indicated 2016 disbursals of $14.7 million (£10.3 million) for education.[114] Furthermore, the IATI data did not list education components for two grants under which DFID had reported 2016 disbursals of $7.3 million (£5.1 million) for education to Human Rights Watch.[115] Upon request for comments, a DFID official explained that the divergence between these figures is caused by differences in how disbursements that fund education are allocated to sector codes such as “education” or “social infrastructure” for reporting purposes, but stated that the divergence does not imply that DFID education funding in Lebanon and Jordan in 2016 was lower than reported to Human Rights Watch.[116]

DFID runs the Development Tracker, a public portal with detailed information, including commitment and disbursement dates, on all funded projects. The tracker is based on IATI data published by DFID.[117] The portal displays a breakdown by different project components and includes a breakdown for multi-annual projects by UK fiscal year.[118]

The UK is the only donor for which Human Rights Watch could find public information on multi-annual education funding commitments for Jordan and Lebanon. The UK committed $114.4 million (£80 million) to support the Jordanian government to provide education for Syrian and vulnerable local children, of which $ 19.9 million (£13.9 million) was disbursed in 2016.[119] It also committed $132.6 million (£92.7) million to the Lebanese Reaching All Children with Education II (RACE II) plan up to 2020, $26.2 million (£18.3) million of which was disbursed in 2016.[120]

Norway

Norway and the US are the only donors examined in this report that pledged funding specifically for education at the London Conference. Norway’s general reporting practices on international aid make it a leader concerning transparency of aid for Syrian children’s education.

The Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs maintains a public database with detailed information on all grant agreements by the ministry and the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD) for which disbursements are planned for up to four years, although commitment dates are only displayed for some grants. The database is updated monthly.[121]

However, it appeared that not all Norwegian education funds allocated under the London Conference pledge in 2016 had been made available to implementing partners as of February 1, 2017. As of that date, the database listed disbursements of $6.6 million (NOK 55.3 million) to Jordan, $23.5 million (NOK 195.7 million) to Lebanon, and $1.8 million (NOK 15 million) to Turkey. Another $480,000 (NOK 4 million) finance health and education services for vulnerable host and refugee communities in Lebanon but are classified as “emergency support” and not as “education.”[122] This sum also includes disbursements under grants which had been awarded in previous years, but is around $28 million less than the $60 million (NOK 500 million) allocated for education in the region that the ministry reported to Human Rights Watch. The ministry informed Human Rights Watch that as of August 24, 2017, funding for education from the Norwegian humanitarian budget in response to the Syria crisis in 2016 – including for education in Jordan, Lebanon, Turkey, Syria, and Iraq – had reached $62.7 million (NOK 522.5 million), and that funds from other 2016 budget lines were also financing education.[123]

The database lists some multi-annual education grants to nongovernmental groups in Lebanon and Turkey, but no multi-annual commitments towards the educational schemes established by the Jordanian and Lebanese governments to achieve universal school enrollment of Syrian and vulnerable host community children.[124]

NORAD aimed to publish information on projects including transactions, planned disbursements and budgets in IATI format on a quarterly basis, starting in December 2015.[125] As of February 17, 2017, however, a query to the IATI registry for projects reported by NORAD via the Development Portal did not yield any results.[126]

Japan

Human Rights Watch is not aware of any systematically-organized public information on the disbursal of funds under the Japanese London Conference funding pledge.[127] The Japanese International Cooperation Agency (JICA) maintains a public database with information on Japanese development projects, but it does not list any projects in Lebanon or Turkey.[128] JICA publishes project data in IATI format, but as of February 17, 2017, the most recent information for projects in Jordan was from 2014.[129]

The Japanese Foreign Ministry told Human Rights Watch that it could not share information on specific projects funded.[130]

IV. Inconsistent Data on School Enrollment

Lack of uniform and regular reporting by host countries makes it difficult to come to definitive conclusions about school enrollment figures among Syrian children in Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey. But none has achieved the goal of universal enrollment. By the middle of the 2016-2017 school year, more than 530,000 Syrian refugee children remained out of education.[131]

At the London Conference, donors and host countries pledged to provide the funding needed to enroll all children in school by the end of the 2016-2017 school year (and beyond). It is therefore essential to have accurate numbers of school-age children, and of children who are not in school. Without reliable figures, it is impossible to assess if appropriate measures are being taken to guarantee all children’s right to education.

Jordan

The London conference used enrollment figures from November 2015 as its baseline. At that time, according to the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), Jordan hosted 227,000 school-age Syrian children ages 5 to 17 registered with the UN refugee agency, of whom 145,458 were in formal education and 31,842 had no access to any education.[132]

The need for host countries to obtain accurate information about enrollment is illustrated by Jordan’s establishment of an education monitoring information system. Data that were collected from December 2016 under the improved system, found that only 125,000 out of 232,868 Syrian children were enrolled in formal education, nearly 68,000 were in non-formal education only, and some 40,210 children had no access to any education—worse than the out-of-school figures before the London Conference.[133] By the end of the 2016-2017 school year, there were still only 126,127 Syrian students enrolled in public schools, with another 67,086 children in non-formal education, and a further 2,593 in accredited programs for out-of-school children.[134]

Lebanon

According to UNICEF, in November 2015, Lebanon hosted 368,000 Syrian refugee children, ages 5 to 17, registered with the UN refugee agency (UNHCR), of whom 180,000 were not accessing formal or non-formal education.[135]

A year later, in December 2016, UNICEF estimated that out of a total of 376,228 Syrian children ages 5 to 17, the number not accessing any education had fallen to 126,732.[136] The latest available update, from March 2017, uses a different age range: there were 423,832 Syrian refugee children, ages 3 to 17, of whom 221,573 were not in formal public education, and 202,259 were in formal public schools.[137] Lebanon aims to enroll all children in pre-school, but because published enrollment numbers frequently include children ages 3 to 18, it is difficult to assess progress towards universal enrollment for children ages 5 to 17.[138]

These numbers undercount out-of-school children since they only capture refugees registered by UNHCR, whom the government estimates comprise only two-thirds of Syrians in Lebanon.[139] In addition, the figures capture both Syrian and other non-Lebanese children.[140] It is not stated if the figures account for dropouts; according to one survey, from September to December 2016, 10 percent of Syrian children dropped out of school.[141]

Although participants in the London Conference committed to bring all Syrian children into school by the end of the 2016-2017 school year, Lebanon presented educational plans at the Conference that fall short of this goal.[142] The 5-year Reaching All Children with Education (RACE) II plan would see fewer than 220,000 “non-Lebanese” children enrolled in formal primary, intermediate, and secondary school, and technical and vocational education and training by 2021.[143]

The plan’s stated aim is merely to reduce the out-of-school rate amongst “non-Lebanese” aged 6 to 14 to less than 25 percent by 2021.[144] Remarkably, the plan aims to have just 4,907 non-Lebanese children enrolled in secondary school and technical and vocational education and training in the 2021 school year. As of March 2017, some 78,300 Syrians ages 15 to 18, the secondary school age in Lebanon, registered with UNHCR.[145]

If the Syrian school-age population remains constant, more than 156,000 children would still not be enrolled in formal education in 2021.[146] This figure does not include those who, in the meantime, will have passed school age without getting an education.

Turkey

Turkish authorities, on which UN agencies rely for data, have provided different figures of the total number of school-age (5 to 17-year-old) Syrian children in Turkey. In November 2015, Turkey hosted 742,000 children, of whom only 289,000 were in school, and 453,000 children were not accessing any education.[147] By June 2016 there were 936,000 school-age Syrian refugee children, UNICEF reported, but another UN planning document put the number at only 845,000 as of August.[148] In December 2016, UNICEF reported, there were 872,536 children, of whom 367,220 remained out-of-school, but a Turkish nongovernmental organization (NGO) report, citing education ministry figures for the same month, stated that of 833,000 Syrian school-age children, 336,000 were not in school.[149]

Of the Syrian refugee children in formal education, roughly 160,000 were enrolled in public schools and about 340,000 were enrolled in so-called Temporary Education Centers (TECs) that teach a modified Syrian curriculum in Arabic.[150] However, in September 2016, Turkey announced plans to close down all TECs within three years, and required all Syrian children entering grades 1, 5, and 9 to enroll in public schools rather than TECs. [151]

V. Unclear Whether Funds Target Education Barriers

With donor support, host country governments should do more to remove obstacles to education and revise policies that have restricted refugee children’s access to education. However, the lack of public information about specific donor-funded projects makes it difficult or impossible to determine the extent to which aid is targeting these barriers.

Human Rights Watch research in 2015 and 2016 identified key obstacles preventing Syrian refugee children from accessing education in Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey:[152]

- Widespread poverty that leaves refugee families unable to pay school-related costs and forces some to rely on child labor or child marriage to cope;

- Lack of access to education for secondary-school-age children and children with disabilities;

- Low-quality teaching that causes dropouts, as teachers are insufficiently trained and often face classrooms of up to 50 students or multiple shifts of classes;

- An urgent need for language training in Lebanon and Turkey;

- The need for greater access to non-formal education to reach children who have been out-of-school for years;

- Delays in getting an identification card required in Turkey to enroll children in school, and

- A failure to address school harassment and discrimination, which Syrian children and their families cite as a substantial cause of dropouts.[153]

These barriers keep Syrian children from accessing education programs that donors support. The Jordanian Ministry of Education has, for example, created 50,000 new spaces for Syrian children in public schools during the 2016-2017 school year.[154] But in January 2017, it reported that less than half of these spaces had been taken up.[155] In Lebanon, the Ministry of Education offered 200,000 spots to Syrian children in the 2015-2016 school year, but just 151,000 non-Syrians were enrolled by the end of the school year.[156]

Human Rights Watch selected one such key obstacle per country, and sought to identify 2016 donor funding to address it using public sources and responses from donors.[157] Of the analyzed IATI data, only data published by the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development and the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation included project sector classifications, such as “lower-secondary education,” that are precise enough to assess if aid addresses key obstacles to education.[158]

We also assessed to what extent the 2016 education chapters of the United Nations-coordinated 3RP regional aid plan in response to the Syria crisis (for Jordan and Turkey), and the Reaching All Children with Education II (RACE II) educational plan address these key obstacles.[159]

Donors may have given funds that target these barriers other than the amounts mentioned. The following analysis aims to illustrate what available information allows us to find out about whether aid targets key barriers to education.

Jordan: Little Information on Support for Secondary and Vocational Education

Secondary-school-age Syrian children are particularly vulnerable to barriers to access to education.[160] Yet little information is available on support to secondary education and vocational training for secondary-school-age refugee children.[161]

In Jordan, there was no public information on the total number of Syrian children enrolled in secondary school. A conservative estimate is that around only 5,400 out of at least 25,000 Syrian 16- and 17-year-olds were enrolled in the 2015-2016 school year. That year only 1,605 out of 2,761 eligible Syrian refugee students sat for the final secondary school exam (the tawjihi) and only 536 passed (33.4 percent).[162]

Human Rights Watch found very little information on support for secondary education and technical and vocational education and training for secondary-school-age children. The Jordan chapter of the UN-coordinated regional aid plan in response to the Syria crisis appealed for $35.4 million in 2016 to enroll 156,000 Syrian children in public schools, but it is not clear how many secondary-school-age children were targeted under the plan.

The plan aimed to enroll 500 Syrian and Jordanian youth in vocational training.[163] The enrollment figures listed as 2016 achievements in plan are not broken down between primary and secondary education, and there is no information on vocational training.[164]

Human Rights Watch found information about only five 2016 contributions that support access to secondary education, or technical and vocational education for secondary-school-age children, in Jordan by the six main donors. Only three of these were included in the publicly available sources discussed in chapter 2 of this report. Germany reported 2016 funding of $6.3 million (€6 million) for two projects that support vocational training for Syrians and Jordanians to Human Rights Watch.[165] Only information on one of these projects, which cost $3.15 million (€3 million), is included in the German International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI) data.[166]

An EU official reported to Human Rights Watch one grant, from 2016 to 2018, of $4.2 million (€4 million) for vocational education and training.[167] The amount of this funding that would benefit children, as opposed to young adults, is not clear. The IATI data published by the UK Department of International Development did not list any support for secondary education in Jordan in 2016, but did so in Lebanon.[168]

The Jordan Response Information System for the Syria Crisis (JORISS) database reported a US grant of $100,000 to a United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) project, that, among other aims, supports secondary school enrollment of Syrians, and a Norwegian grant of $714,000 to a project for “learning support services for youth in camps.”[169]

Lebanon: Lack of Clarity on Funding to Alleviate Poverty-Related Barriers to Education

The dire legal and economic situation of Syrian refugees in Lebanon is an obstacle to education. Human Rights Watch tried to track aid to projects which provide livelihood assistance to allow refugee families in Lebanon to send their children to school, and which provide support with school-related costs.[170]

A 2016 survey found that 71 percent of surveyed Syrian refugee households lived below the daily poverty line of $3.84 per person in Lebanon, most were in debt, and that costs associated with schooling were the most frequently-cited reason for children to be out of school.[171 Another study found that poverty is a main factor behind high rates of child marriage for Syrian refugee girls, most of whom do not continue their education after marriage.[172]

European Union officials told Human Rights Watch in June 2016 that the EU was supporting a UNICEF pilot project to provide unconditional cash grants to Syrian families with children in two areas of Lebanon, intended in part to help families offset school-related costs.

Lebanon’s five-year RACE II educational plan includes a pilot cash-transfer program, but the plan’s published costing analysis does not include the program.[173] The plan also aims to subsidize school supplies for all students in formal and non-formal education as well as school transport for 50 percent of students in formal education and for 75 percent of students in non-formal education by 2021.[174] RACE II envisages a case-management system to address child labor and early marriage, but the Lebanese Education Ministry did not include it in the published costing figures.[175]

RACE II addresses these key economic barriers to education, and Lebanon presented it as the central instrument to realize universal enrollment of Syrian and vulnerable Lebanese children at the London Conference.[176] Human Rights Watch could not find comprehensive information on the funding made available under the plan in 2016. The Project Management Unit in the Lebanese Ministry of Education and Higher Education, which manages the plan, replied to our requests but did not provide figures.[177]

Transparency International reports that donors are reluctant to directly support Lebanese government agencies due to perceptions of corruption.[178] Many donors prefer instead to provide RACE II funds to UNICEF, which issued more than 50 private reports to donors in 2016 that include “the full utilization details of specific financial contributions.”[179] UNICEF maintains a global public database of projects it supports, but apparently in contrast to the private reports to donors, the database does not provide detailed information. [180]

All available public information on funding for RACE II, and all information about 2016 education funding that the six donors assessed in this report shared with Human Rights Watch upon request, reveals only two donor country grants for RACE II.[181] The UK gave $26.2 million (£18.3 million) for RACE II during the 2016-2017 budget year and promised a total of $132.6 million (£92.7 million) up to 2020.[182] And according to IATI data published by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development, Germany supported RACE II with $31.5 million (€30 million) in 2016, as of December 16, although the ministry reported to Human Rights Watch that it had given $34.4 million (€32.8 million) as of December 12.[183] In addition, an official of the EU’s Directorate-General NEAR stated at a hearing of the European Parliament’s Development Committee that the EU had given $44.6 million (€42.5 million) to RACE II.[184]

It seems likely that other donors allocated funds for RACE II, but did not clearly report them. The Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affair’s Grants Portal reported 2016 funds of $18.2 million (NOK 152 million) for education activities by UNICEF in Lebanon, and the US Foreign Aid Explorer lists US aid of $22 million for the same purpose during the 2016 US Fiscal Year.[185] These sums probably included funds for RACE II.[186]

Human Rights Watch could not find information about other 2016 funding for projects in Lebanon that provide livelihoods support to allow refugee families to send their children to school or to help with school-related costs. The sector classification used for IATI data does not allow browsing for projects that help with school-related costs or cash allowances conditional on school attendance.[187] The only 2016 project to address child labor that Human Rights Watch could identify has a budget of $690,000 from Norway.[188]

At the London conference, Lebanon proposed various schemes to create up to 350,000 jobs, 60 percent of which should be for Syrians.[189] However, in 2016, only 216 work permits were issued to refugees, depriving many of the possibility to obtain an income, and only 7,800 Lebanese and non-Lebanese participated in public work programs.[190] In February 2017, the World Bank approved a $200 million loan to build or repair 500 kilometers of roads in Lebanon, a scheme that should create jobs for Syrians and Lebanese.[191] In March, Lebanon’s labor minister pledged to provide work permits to Syrians in agriculture, construction, and sanitation.[192]

Turkey: Syrian Teachers as a Key Resource in Educating Refugee Children

Syrian students and parents in Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey told Human Rights Watch that poor-quality teaching and overcrowded classrooms had caused students to drop out.[193] Qualified Syrian teachers amongst the refugee population could be an important resource to address this problem, but Turkey is the only of the three countries that allows them to teach in accredited programs as “volunteer teachers”.

The Turkey chapter of the 2016 UN-coordinated regional aid plan for the Syria crisis appealed for $1.4 million to train 56,000 teachers to support refugee children and for $32 million for stipends and training of Syrian “volunteer” teachers.[194] The latter appeal appears to have been met in its entirety: Germany funds the stipends of 8,000 Syrian “volunteer” teachers with $41.7 million (€40 million) during the 2016-2017 school year,[195] which allowed UNICEF to pay stipends to all 13,000 “volunteer teachers” in the country by December 2016.[196]

The majority of Syrian teachers employed in Turkey worked at accredited Temporary Education Centers, often established by members of the Syrian refugee community. The education ministry plans to close all TECs by the end of the 2018-2019 school year and integrate the students into the public school system, and has closed some TEC and required that all Syrian children in grades 1, 5, and 9 enroll in public schools. It is not clear if Syrian teachers will have the opportunity to work in the public school system after the TECs are closed.

Acknowledgments

This report was researched and written by Simon Rau, a Mercator Foundation Fellow with the Children’s Rights Division. Bill Van Esveld, senior children’s rights researcher, contributed to and edited the report. Bede Sheppard, deputy children’s rights director; Bill Frelick, refugee division director; Lama Fakih, deputy Middle East and North Africa director; and Bassam Khawaja, Lebanon researcher, also reviewed. Senior legal advisor Clive Baldwin provided legal review. Senior editor in the Program Office, Danielle Haas, edited the report.

Production assistance was provided by Helen Griffiths, children’s rights coordinator; Olivia Hunter, photo and publications coordinator; Jose Martinez, senior coordinator; and Fitzroy Hepkins, administrative manager.

Human Rights Watch thanks the governments, United Nations agencies, and nongovernmental organizations who provided information for this report.