The warring parties in Syria are to resume talks in Geneva on January 25 with the aim of ending a conflict that has killed hundreds of thousands of Syrians and displaced millions. What will it take for the talks to succeed?

In October in Vienna, the main foreign actors in the war, including Russia, adopted guiding principles for the talks. They speak of the eventual defeat of the self-proclaimed Islamic State (ISIS) “and other terrorist groups,” maintenance of Syria’s prewar borders, and the protection of minority groups and state institutions.

Yet major points of dispute remain, and the Vienna principles outline no plan to build the trust among the warring parties needed to facilitate difficult compromises. Diplomacy will not be enough if the warring parties continue the attacks on civilians and other atrocities that are driving Syrians apart.

The war has continued for so long in part because both the Syrian government and the armed groups aligned against it believed that they could prevail militarily. Russia’s entry into the war may have helped to dispel those illusions. Its airpower has been enough to bolster the Syrian government against collapse but not to make significant progress against the opposition. Meanwhile, the rise of ISIS and its demonstrated ability to attack in Europe, as well as the mass exodus of Syrian refugees, have led many external actors to renew their push for a political compromise. They hope to encourage their Syrian allies to fight ISIS and other extremist groups like Jabhat al-Nusra rather than each other.

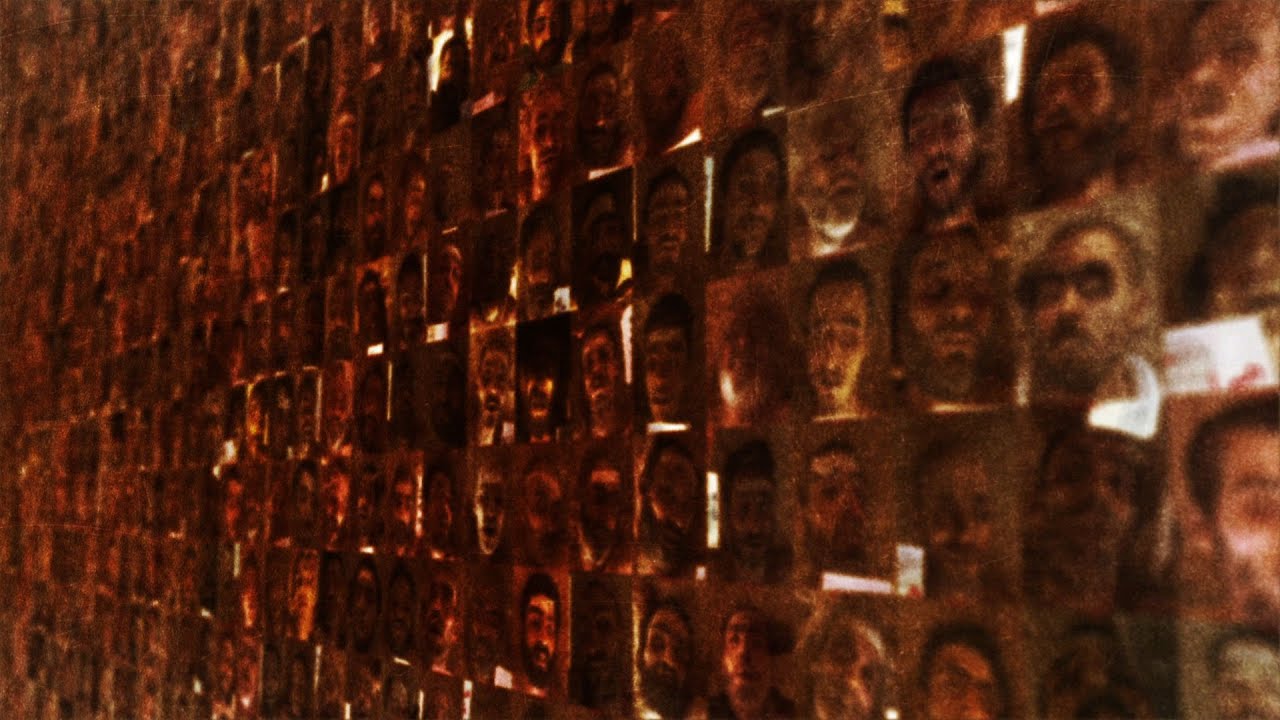

One of the biggest open questions for negotiation concerns the fate of President Bashar al-Assad and other senior officials. They are the architects of a brutal strategy of indiscriminate attacks in populated areas held by the armed opposition, as well as sieges imposed on civilian populations and the mass torture and execution of prisoners. Although no reliable figures exist for the total number of civilians killed in the Syrian war, there is broad agreement that the Syrian government has been responsible for a significant majority.

Because of the government’s history of atrocities, the opposition demands that Assad leave power. On the other hand, with the possible exception of extremist groups, no one has an interest in the Syrian state collapsing, since the loss of its security forces and judicial system could yield chaos even worse than today’s conflict, especially for Syria’s minorities. Because Assad’s abrupt departure might deal a symbolic blow that would jeopardize the Syrian state, a managed transition with an orderly transfer of power to a new government or transitional authority would be a compromise that should be in most parties’ interest.

In a recent interview, President Vladimir Putin seemed to recognize that eventually Assad must go, but he said he would consider a replacement only after a new constitution and elections. The Vienna declaration speaks of UN-supervised elections. But given Syria’s turmoil and displacement, credible elections will take a long time to hold. It is extremely unlikely that the opposition would settle for such an indefinite timetable when ridding the country of Assad and his henchman is its primary goal.

Instead, a more productive route would be to establish a coalition government by agreement, tasked with running the country pending constitutional reform and elections. The Vienna declaration calls for “credible, inclusive, non-sectarian governance.” Such a government would need to be led by figures with credibility among both Syria's Sunni majority and the Alawite and other minorities that have largely entrusted their fate to the current government.

Syrians participating in the negotiations would determine the members of this coalition. But the possibility for compromise—and the likelihood of the Vienna principles being met—would increase greatly if the international community including Russia demanded that the new government exclude people from any side who, through a fair, open, and contested process, are found responsible for serious abuses. That is likely to include Assad, his chief lieutenants, as well as leaders of armed groups that have been responsible for regular atrocities.

As it sees the writing on the wall, the Assad government will likely seek amnesty for its crimes. Russia should join other nations in rejecting that request. As a general rule since the early 1990s, the international community has rightly refused to give its imprimatur to amnesties for mass atrocities. Rejection is required by international law, respects the victims, and avoids encouraging further atrocities.

In any event, an amnesty in Syria would not guarantee against prosecution. If a future Syrian government joined the International Criminal Court and consented to retroactive jurisdiction, the court would not accept an amnesty for mass atrocities. Foreign courts exercising universal jurisdiction over alleged Syrian war criminals found on their territory would also be free to ignore an amnesty. Precedents from Argentina, Chile, and Peru show that even in countries where the atrocities occurred, amnesties granted under pressure of violence can be ruled invalid.

That said, Assad and other officials can hardly be expected to deliver themselves directly to The Hague. As a practical matter, they could either use their power in Syria to shield themselves or, if weakened, flee to Moscow or Tehran, leaving for another day the issue of their prosecution and trial.

Achieving an accord along these lines will require difficult compromises by all involved. That necessitates a level of trust among the warring factions that is currently lacking. It is difficult to shake hands with opponents who are killing one’s families and neighbors.

That is why it is so important to stop the slaughter of civilians. All sides have been responsible for such killing, but as noted, measured by the number of victims, Syrian government forces are mainly responsible. Because the Syrian government today depends for its survival in large part on Russia’s military support, the Kremlin has enormous influence in Damascus. It should use that influence to press Assad to stop attacking civilians, as well as besieging civilian populations, and torturing and executing perceived opponents.

Taking these steps are not just a byproduct of a deal in Geneva. They are a prerequisite. As the Geneva talks recommence, negotiators should not treat the atrocities as a sideshow, as the Vienna declaration did. Instead, they should use their substantial collective influence to insist on an end to them now.