(Brussels) – The ICC is considering challenges to the court’s jurisdiction to try ICC suspects Saif al-Islam Gaddafi, the son of Libya’s former ruler Muammar Gaddafi, and Abdullah Sanussi, the Gaddafi-era intelligence chief.

Libya says it is investigating both men for their role during the government’s 2011 crackdown on protests and prior alleged corruption. Libya also contends that the scope of its Sanussi investigation extends back to the 1980s into serious human rights violations during Gaddafi’s rule, including the June 1996 killing of more than 1,200 prisoners in Tripoli’s Abu Salim prison.

United Nations Security Council Resolution 1970, which referred Libya to the ICC, requires the Libyan authorities to cooperate fully with the court – a binding requirement under the UN Charter, even though Libya is not a party to the treaty that established the court. This cooperation includes abiding by the court’s decisions and requests, as well as adhering to the court's procedures. Under ICC rules, a state that wants to try a suspect for a case already opened by the ICC must challenge the court's jurisdiction through a legal submission.

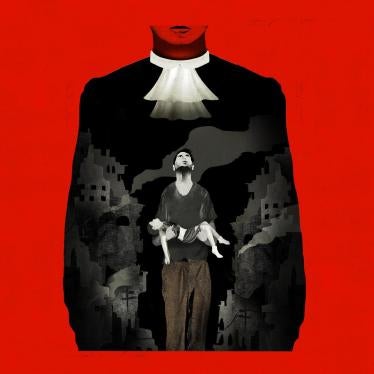

“Libya understandably wants to see those responsible for past crimes brought to justice,” said Richard Dicker, international justice director at Human Rights Watch. “As Libya goes forward with its bids at the ICC, it should demonstrate its intention both to abide by the rule of law at home and to respect its international obligations.”

Human Rights Watch was recently allowed a visit with Sanussi, seemingly in private, on April 15, 2013, and visited with Gaddafi in Zintan on December 18, 2011.

The following Q&A looks at the relationship between the ICC and Libya.

I. The International Criminal Court (ICC) Libya Investigation

1. What is the source of the International Criminal Court's jurisdiction in Libya?

2. Is Libya required to cooperate with the ICC?

3. What happens if Libya does not cooperate with the ICC?

4. Has the court issued any arrest warrants related to the ICC prosecutor's investigation in Libya?

5. Are the three ICC arrest warrants still outstanding?

6. Will the ICC prosecutor conduct other investigations or open new cases in Libya?

8. Can the ICC hold its proceedings in Libya?

II. Libya's “Admissibility Challenges”

14. Who represents Saif al-Islam Gaddafi’s interests at the ICC?

15. How did the OPCD come to initially represent Gaddafi at the ICC, and why was it later replaced?

16. Did the OPCD, as Gaddafi’s initial counsel at the ICC, visit him in Libya?

17. Has Gaddafi's current lawyer, John Jones, visited him in Libya?

18. Who represents Sanussi's interests at the ICC?

19. Has Sanussi received visits from the lawyers representing him at the ICC?

21. What happened after Libya filed its first admissibility challenge?

22. What is the basis for Libya’s first admissibility challenge on the case against Gaddafi?

23. What are the other parties’ positions on Libya’s first challenge?

24. What is the basis for Libya’s admissibility challenge on the case against Sanussi?

26. What is Libya asking the ICC judges to rule?

28. Are the parties free to appeal the judges’ decision on Libya’s challenges?

29. How many times can Libya challenge the admissibility of the cases against the two ICC suspects?

III. Due Process and National Proceedings

30. Where are the two ICC suspects currently being held?

31. Does Gaddafi have a defense lawyer for proceedings against him in Libya?

32. Has Gaddafi been brought before a judge in Libya regarding his detention?

33. Hasn’t Gaddafi already appeared in court in Zintan? What were those proceedings about?

35. Are there international legal standards on detention to which Libya is bound?

36. Has Human Rights Watch been granted access to visit the two ICC suspects?

38. Where will the ICC suspects' domestic trials take place in Libya?

39. Who is in charge of the domestic cases against the ICC suspects in Libya?

40. Does Human Rights Watch believe that the two ICC suspects will receive fair trials in Libya?

I. The International Criminal Court (ICC) Libya Investigation

1. What is the source of the International Criminal Court's jurisdiction in Libya?

On February 26, 2011, the United Nations Security Council adopted resolution 1970 by a vote of 15-0 referring the situation in Libya to the ICC. Under the Rome Statute, the ICC's founding treaty, the Security Council may refer a situation in any country to the ICC prosecutor under its Chapter VII mandate if it determines that the situation threatens international peace and security.

Resolution 1970 gave the court ongoing authority over events in Libya beginning on February 15, 2011.

2. Is Libya required to cooperate with the ICC?

Yes. Security Council resolution 1970 requires the Libyan authorities to cooperate fully with the court—a binding requirement under the UN Charter, even though Libya is not a party to the treaty that established the court. Security Council resolution 2095, adopted on March 14, reiterates Libya's obligation to cooperate with the ICC. This cooperation includes abiding by the court’s decisions and requests, as well as respecting the immunity of court officials, as stipulated in article 48 of the court’s treaty.

Libya has promised to abide by its obligations. In a recent submission to the ICC, Libya states it “does not dispute that it is bound by Security Council Resolution 1970.” Previously, in a letter to the Security Council on June 20, 2012, the Libyan National Transitional Council (NTC), then the ruling authority, reiterated its commitment to cooperate with the ICC. The NTC had also pledged its cooperation in a November 2011 letter to the ICC judges and an April 2011 letter to the ICC prosecutor.

3. What happens if Libya does not cooperate with the ICC?

Article 87 of the Rome Statute permits the court to issue a finding of non-cooperation. Because Libya is before the ICC as a result of a Security Council referral, such a finding is sent to the Security Council for follow-up. The Security Council then has a range of options, including resolutions, sanctions, and presidential statements.

For example, the court issued its first formal finding of non-cooperation in connection with its Darfur investigation. In that case, the ICC issued arrest warrants for three people for serious crimes. Following three years in which Sudan failed to hand over any of the suspects, the ICC prosecutor on April 19, 2010, asked the court to issue a finding of non-cooperation in the execution of warrants for two of the suspects. On May 25, 2010, an ICC pre-trial chamber decided to send the finding of non-cooperation on the warrants to the Security Council. The Council has yet to take any action in response to the ICC's finding.

4. Has the court issued any arrest warrants related to the ICC prosecutor's investigation in Libya?

Yes. On June 27, 2011, ICC judges issued arrest warrants for the former Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi, his son Saif al-Islam Gaddafi, and Libya's former intelligence chief, Abdullah Sanussi. The three were wanted on charges of crimes against humanity for their roles in attacks on civilians, including peaceful demonstrators, in Tripoli, Benghazi, Misrata, and other locations in Libya. The ICC warrants apply only to events in Libya beginning on February 15, 2011.

5. Are the three ICC arrest warrants still outstanding?

The ICC’s case against Muammar Gaddafi was terminated following his death on October 20, 2011. The arrest warrants for the other two suspects remain in force. This means that Libya’s legal bids to try Saif al-Islam Gaddafi and Sanussi domestically do not affect the validity of the ICC warrants for the two suspects (see questions 11, 12, and 26 below).

6. Will the ICC prosecutor conduct other investigations or open new cases in Libya?

In her last report to the UN Security Council, in May 2013, the ICC prosecutor, Fatou Bensouda, said her office planned to take a decision regarding a second case in the near future, and would consider additional cases after that depending on Libya’s progress in implementing a comprehensive strategy to address crimes.

Specifically, Bensouda said her office was continuing its investigations into a second case “with a focus in particular on pro-Gaddafi officials outside of Libya.” In terms of crimes committed by rebel forces, the prosecutor said her office was collecting information about allegations of “killings, looting, property destruction, and forced displacement by Misrata militias” of displaced former residents of the Libyan town of Tawergha to determine whether a new case should address these allegations.

The ICC has ongoing jurisdiction over war crimes and crimes against humanity committed in Libya since February 15, 2011, taking into account, among other factors, whether the Libyan authorities are willing and able to prosecute those responsible for these crimes. Human Rights Watch has called on the ICC Office of the Prosecutor to examine the crimes exempted from domestic prosecution by laws recently passed in Libya, and, if appropriate, to investigate them.

7. Why is the ICC prosecutor investigating crimes committed in Libya but not investigating crimes in Syria?

Syria is not a state party to the Rome Statute. For the ICC to begin an investigation, either the UN Security Council would have to refer the situation to the ICC prosecutor, as it did for Libya, or Syria would have to accept the court's jurisdiction. Human Rights Watch has urged the Security Council to refer the situation in Syria to the ICC.

On January 14, a letter was sent to the Security Council on behalf of 58 states calling for it to refer the situation in Syria to the ICC. The Security Council has taken no action in response.

8. Can the ICC hold its proceedings in Libya?

Although the ICC is headquartered in The Hague, the court's treaty leaves open the possibility of holding proceedings in other locations. A recommendation to change the place where the court sits can be made by the ICC prosecutor, the defense, or a majority of the court’s judges. The court needs the consent of the state where the court intends to sit.

II. Libya's “Admissibility Challenges”

9. On May 1, 2012, Libya challenged the admissibility of the ICC's case against Saif al-Islam Gaddafi, and on April 2, 2013, Libya also challenged the admissibility of Abdullah Sanussi’s case. What is an “admissibility challenge?”

If a concerned state wishes to try an ICC suspect domestically for crimes outlined in an existing ICC arrest warrant, the authorities may challenge the court's jurisdiction over the case through a legal submission called an "admissibility challenge." Under existing ICC case law, an admissibility determination involves a two-stage inquiry by the court.

First, for a state to bring a successful challenge, it must demonstrate that it has ongoing national proceedings encompassing both the person and the conduct that are the subject of the ICC case. The state must provide the court with “concrete, tangible and pertinent evidence that proper investigations are currently ongoing.” A finding of inaction at the national level would result in an unsuccessful challenge.

Where such national proceedings are found to exist, the court then considers whether the state is genuinely willing and able to conduct those proceedings. This second inquiry only becomes relevant if the first requirement is satisfied. The Rome Statute provides guidance about the meaning of "unwillingness" and "inability" in article 17.

When considering a state's ability to genuinely conduct national proceedings, the Rome Statute instructs the judges to consider "whether, due to a total or substantial collapse or unavailability of its national judicial system, the State is unable to obtain the accused or the necessary evidence and testimony or otherwise unable to carry out its proceedings."

When considering a state's willingness, the Rome Statute instructs the judges to consider, having regard to principles of due process recognized by international law, whether:

- the national proceedings are for the purpose of shielding the person concerned from criminal responsibility;

- there has been an unjustified delay in the national proceedings that, under the circumstances, is inconsistent with an intent to bring the person concerned to justice; or

- the proceedings were not or are not being conducted independently or impartially, and they were or are being conducted in a manner that, under the circumstances, is inconsistent with an intent to bring the person to justice.

Ultimately, it is up to the ICC judges to determine whether national proceedings exist that meet the criteria for a successful admissibility challenge.

10. What if Libya intends to investigate the two suspects for the same crimes as those in the ICC's arrest warrants? Is that enough to successfully challenge the admissibility of the cases before the ICC?

An ICC pre-trial chamber held in the Kenya situation that a promise to investigate by the state authorities is not enough to stop existing ICC cases. On March 31, 2011, the Kenyan government challenged the admissibility of the two Kenyan cases before the ICC, involving six people, citing its plans to begin or continue investigations of those responsible for the country’s post-election violence in 2007-2008 in the context of reforms mandated by the new August 2010 constitution. However, the ICC pre-trial chamber rejected the government’s admissibility challenge. The judges found no evidence that the Kenyan government was actually investigating any of the six people named in the two cases.

On August 30, 2011, an ICC appeals chamber confirmed the pre-trial chamber decision.

11. Since the ICC arrest warrants against Gaddafi and Sanussi remain valid, why has Libya not handed them over to the ICC?

Libya’s May 1, 2012 challenge to the admissibility of the case against Saif al-Islam Gaddafi did not, under Article 19 of the Rome Statute, affect the validity of the warrant for his arrest. However, Libya was granted permission to postpone his surrender to the ICC, pending a decision by the court's judges on the admissibility challenge. The ICC judges made clear that Libya must take all necessary measures during the postponement period to ensure that Gaddafi can be immediately surrendered to the ICC should Libya fail in its bid to pursue the case domestically.

When Libya also challenged the admissibility of the case against Sanussi, on April 2, it said that it was exercising its “right” to postpone his surrender to the ICC pending a ruling by the judges on the challenge. However, a previous court decision at the ICC indicates that it is the ICC judges who have the authority to decide whether a state may postpone surrendering a suspect. It appears, therefore, that Libya must request permission from the judges. On April 24, Sanussi’s lawyers argued that the issue of the postponement of Sanussi’s surrender to the court is a matter for the ICC judges to rule on.

The ICC judges had ordered Libya on February 6 to surrender Sanussi to the court immediately and to refrain from any action that would frustrate, hinder, or delay Libya's compliance with this obligation. Libya's subsequent request to appeal that decision was rejected on February 25. On March 19, Sanussi's legal team asked the ICC judges to find that Libya had failed to comply with the court's surrender order and to refer the matter to the Security Council for action.

12. Could Libya have asked to postpone Sanussi’s surrender to the ICC based on its May 1 admissibility challenge?

No. The ICC judges concluded that the scope of Libya’s May 2012 admissibility challenge does not cover the Sanussi case. The judges also held that a promise to challenge the admissibility of a case is not enough to justify a request to postpone the surrender of a suspect to the court.

13. How have Libya’s admissibility challenges affected the ICC prosecutor’s investigation of the two suspects?

In line with the Rome Statute, the ICC prosecutor had to suspend the investigation into Saif al-Islam Gaddafi until the court rules on Libya’s first admissibility challenge. Because the scope of that challenge did not cover the Sanussi case, the ICC prosecutor’s investigation into Sanussi’s activities continued until Libya filed its challenge on his case, on April 2.

14. Who represents Saif al-Islam Gaddafi’s interests at the ICC?

On April 17, the ICC judges provisionally appointed John R.W.D. Jones, a British lawyer, to represent Gaddafi at the ICC. Gaddafi had, until then, been represented by the court’s Office of Public Counsel for the Defence (OPCD).

15. How did the OPCD come to initially represent Gaddafi at the ICC, and why was it later replaced?

On March 3, 2012, Gaddafi signed a declaration stating that he was willing for the court’s Office of Public Counsel for the Defence (OPCD) to represent him at the ICC. On this basis, the ICC judges appointed OPCD lawyers Xavier-Jean Keïta and Melinda Taylor as temporary counsel for Gaddafi on April 17, 2012.

In a November 2012 decision, the ICC judges re-iterated that the appointment of these lawyers was intended to be provisional and said that ongoing representation by the OPCD, an entity within the court’s registry, risked compromising the perception of the court’s impartiality. The judges concluded that the positions of the parties in the admissibility proceedings must be clearly distinguished from those of the court, and on this basis, underlined the need to secure “regular” counsel for Gaddafi.

On March 4, the OPCD asked the ICC judges for permission to withdraw, saying that imminent staff cutbacks would affect its ability to represent Gaddafi effectively. At the same time, the OPCD asked the judges to appoint Jones, a British lawyer, as replacement counsel for Gaddafi. In an April 17 decision, the judges granted the OPCD's request to withdraw and provisionally appointed Jones until Gaddafi "exercises his right to freely choose counsel ... or until the definitive disposal of proceedings related to the Admissibility Challenge."

16. Did the OPCD, as Gaddafi’s initial counsel at the ICC, visit him in Libya?

Yes. Office of Public Counsel for the Defence (OPCD) lawyers visited Gaddafi twice during his detention. The OPCD first met with him on March 3, 2012, following an order by the ICC judges, who noted the importance of informing Gaddafi of the status of ICC proceedings as well as the appointment of the OPCD to represent his interests at the court pending his selection of a lawyer. On March 5, 2012, the OPCD, among other things, gave an account to the ICC judges of the non-confidential aspects of the visit.

On June 6, 2012, four ICC staff members, including Melinda Taylor, then counsel for Gaddafi from the OPCD, traveled to meet with Gaddafi in a second visit authorized by the ICC judges and agreed to by Libya. The ICC judges mandated that this visit was to be conducted on the basis of full respect for the confidentiality of communication between Gaddafi and the lawyers. The delegation was also sent to discuss with Gaddafi options for his legal representation at the court. Following a brief meeting with Gaddafi on June 7, the four ICC officials were arbitrarily detained in Zintan for nearly four weeks.

17. Has Gaddafi's current lawyer, John Jones, visited him in Libya?

No. No visit has taken place between Gaddafi and his lawyer, since his provisional appointment on April 17.

18. Who represents Sanussi's interests at the ICC?

The ICC provisionally acknowledged the appointment of Benedict Emmerson, a London-based lawyer, as counsel for Sanussi on January 15. Rodney Dixon, Amal Alamuddin, Anthony Kelly, and William Schabas are also listed on court filings as representing Sanussi at the court.

19. Has Sanussi received visits from the lawyers representing him at the ICC?

No. The lawyers representing Sanussi at the ICC have not visited him in Tripoli. On February 6, the ICC judges asked Libya to arrange, in consultation with the ICC registrar, a privileged visit between Sanussi and his ICC defense team. As of May 12, no meeting had yet taken place to Human Rights Watch’s knowledge.

In its April 2013 admissibility challenge, Libya states that it first wants to conclude a memorandum of understanding (MOU) with the ICC before arranging a visit by Sanussi’s lawyers. Libya says that the recent appointment of a new general prosecutor by the Libyan authorities has delayed finalization of the MOU, but that it intends to address the issue “as a matter of priority.” Libya later alleged in an April 23 filing that it had extended an invitation to Sanussi’s lawyers, through the ICC registry, to visit him in Libya.

Sanussi’s lawyers contend that Libya has ignored the ICC judges’ order requiring that arrangements be made for a visit by the lawyers engaged to represent him, and that the authorities have not made the necessary arrangements for a visit "despite countless requests to do so."

According to the ICC prosecutor’s recent report to the UN Security Council on her Libya investigation, the ICC judges asked the court’s registrar to provide a report on the status of arrangements for a visit by May 3.

20. Who represents victims’ interests at the ICC in the admissibility challenge proceedings regarding Gaddafi's case?

On May 4, 2012, the ICC judges appointedPaolina Massidda from the ICC Office of Public Counsel for Victims (OPCV)as legal representative of victims who had already communicated with the court in relation to the Libya case.

21. What happened after Libya filed its first admissibility challenge?

After Libya challenged the admissibility of the case against Gaddafi on May 1, 2012, the ICC judges invited the ICC prosecutor, the ICC Office of Public Counsel for the Defence (OPCD), the ICC Office of Public Counsel for Victims (OPCV), and the Security Council to file responses to the challenge. The judges also granted two non-governmental organizations—Lawyers for Justice in Libya and the Redress Trust—permission to file observations jointly as amicus curiae on a number of specific issues, including the state of the Libyan judiciary as well as the security situation in the country. All these parties subsequently filed responses, except for the Security Council, which informed the court that it would not.

After receiving these responses, the ICC judges held a hearing on October 9 and 10, at which Libya, the ICC Prosecutor's Office, the OPCD, and the OPCV made further oral representations. On December 7, ICC judges asked Libya to file further written submissions, to substantiate with evidence the assertions in its admissibility challenge that proper domestic investigations into Gaddafi’s case were ongoing. The ICC prosecutor, the OPCD, and the OPCV all responded to Libya's further submissions, and Libya filed its final reply on March 4.

22. What is the basis for Libya’s first admissibility challenge on the case against Gaddafi?

In its admissibility challenge, Libya claims that it is actively investigating Gaddafi for the same underlying allegations of murder and persecution that form the basis for the ICC arrest warrant against him. Further, Libya asserts that it is willing and able to investigate Gaddafi and, as appropriate, to prosecute him.

When the ICC judges asked Libya to substantiate with evidence its assertion that proper domestic investigations into Gaddafi’s case were ongoing, Libya argued that national disclosure laws prevented it from providing a full record of the investigative measures taken to date. Libya noted that it had provided the court with a sample of the material it had compiled relating to Gaddafi’s case to show that it was investigating a substantial number of the allegations underpinning the ICC warrant. In addition, Libya proposed having the ICC judges send a representative to Libya to review the case file and/or allow Libya six additional weeks to provide further evidence samples, as necessary. In its final submission on the matter, Libya also told the court that it would be in a better position to provide additional evidence once a new general prosecutor had been appointed. It later notified the court that the general prosecutor post was officially filled on March 25.

23. What are the other parties’ positions on Libya’s first challenge?

Office of the Prosecutor

In its first response to Libya's challenge, the Office of the Prosecutor said that Libya had taken concrete steps to investigate Gaddafi for the same conduct at issue in the case against him before the ICC, satisfying the first limb of the admissibility inquiry. But the prosecutor said there were questions about Libya's ability to move the case against Gaddafi forward.

Later, when the ICC judges requested further written submissions from Libya, they concurrently asked the prosecutor to update her office's initial assessment on the admissibility of the case, taking into account the additional material provided by Libya and other information gathered by the prosecutor.

In an updated assessment to the judges, the prosecutor concluded that Libya had not provided enough evidence to demonstrate it was investigating the same case as the one before the ICC. At the same time, the prosecutor argued that Libya should be given “a reasonable and final period of time” to provide additional materials to support its challenge, in due consideration of the post-conflict challenges the country currently faces.

Office of Public Counsel for the Defence (OPCD)

The OPCD, then representing Gaddafi’s interests at the ICC, asked the ICC judges to dismiss Libya's challenge. Gaddafi's lawyers argued that Libya has failed to discharge its burden to show that it is actively investigating the same case as the one before the ICC, and that the Libyan authorities are neither genuinely willing nor able to conduct proceedings against Gaddafi. They said that Libya has failed to present evidence that is sufficiently comprehensive and credible to demonstrate that it is actively investigating Gaddafi and that there is a connection between the domestic proceeding and the case before the ICC.

Further, the OPCD contended that there is no reason to consent to Libya's request for more time to present further evidence. It said that Libya has been given ample opportunity to substantiate its challenge. It also asked the ICC judges to dismiss Libya’s notification concerning the appointment of a new general prosecutor, describing it as a “delaying tactic.”

Office of Public Counsel for Victims (OPCV)

The OPCV asked the ICC judges to reject Libya's challenge. It said Libya has not presented sufficient evidence to demonstrate that it is investigating Gaddafi for the same conduct that forms the basis of the case against him before the ICC.

24. What is the basis for Libya’s admissibility challenge on the case against Sanussi?

As in its first challenge, Libya essentially claims that it is actively investigating Sanussi in relation to the case outlined in the ICC’s arrest warrant against him. Libya argues that the evidence submitted to support its challenge shows that Libya is carrying out concrete and specific steps to investigate its case against Sanussi. Further, Libya asserts that it is willing and able to carry out a genuine investigation into the case.

25. Now that Libya has challenged the admissibility of the case against Sanussi, what will happen next at the court?

According to the ICC prosecutor’s recent report to the UN Security Council on her Libya investigation, the ICC judges issued a decision on April 26 on the procedure to be followed. In the decision, the prosecutor reports that the judges have invited other parties including counsel representing Sanussi and the Office of Public Counsel for Victims to respond to Libya’s challenge by June 14.

The ICC prosecutor said her office had already submitted its response to Libya’s challenge on April 24, asserting the position that the case against Sanussi is inadmissible at the ICC and should therefore be prosecuted by the Libyan authorities. However, the prosecutor added that the ICC “including the Prosecution, should take steps to monitor the ongoing progress of Libya’s investigation and prosecution to ensure that it continues to be able to investigate and prosecute the same case as is before the ICC.”

26. What is Libya asking the ICC judges to rule?

With respect to its first challenge, Libya is principally asking the ICC judges to declare the case against Saif al-Islam Gaddafi inadmissible at the ICC, and to concurrently quash the court’s request for his surrender to The Hague. In the context of the ICC judges’ request for Libya to furnish further evidence that nationalinvestigations into Gaddafi’s case are ongoing, Libya has asked the judges for six additional weeks to provide further evidence samples as necessary and/or send a representative to Libya to review the case file.

In its second admissibility challenge, Libya likewise asks the ICC judges to declare the case against Sanussi inadmissible at the ICC, and to concurrently quash the court’s request for his surrender to The Hague. Alternatively, Libya invites the ICC judges to declare the case inadmissible on a temporary basis "subject to ongoing monitoring and reporting on the progress of the trial by both the [Office of the Prosecutor] and the Libyan Government."

27. Libya has suggested that the ICC could monitor domestic proceedings against Gaddafi and Sanussi. Is there a basis for this in the ICC treaty?

Libya has suggested that, in the case of a finding of inadmissibility, the ICC could nonetheless monitor Libya’s domestic proceedings against the two suspects in one of two ways. First, Libya argues that the ICC Office of the Prosecutor is empowered to alert the ICC judges if new facts emerge that would require a reconsideration of their decision on admissibility. Second, Libya argues that the ICC judges could decide to remain seized of the matter and order the ICC prosecutor or other parties to monitor the proceedings in Libya and submit periodic progress reports to the ICC.

Under Article 19(10) of the Rome Statute, the ICC prosecutor may ask the ICC judges to review a finding of inadmissibility if she is fully satisfied that new facts have surfaced that negate the basis of the court's original ruling on the matter. Otherwise, the treaty does not explicitly provide for the active monitoring of domestic proceedings following a finding of inadmissibility.

28. Are the parties free to appeal the judges’ decision on Libya’s challenges?

The Rome Statute provides that "either party" may appeal a decision on admissibility. In the past, both concerned states and the defense have lodged appeals on admissibility decisions. An admissibility ruling must be appealed within five days of notification of the decision.

29. How many times can Libya challenge the admissibility of the cases against the two ICC suspects?

In line with the Rome Statute, Libya can challenge the admissibility of the ICC’s cases once. Any additional challenges can be made only in exceptional circumstances and with the ICC judges’ permission.

III. Due Process and National Proceedings

30. Where are the two ICC suspects currently being held?

Anti-Gaddafi forces apprehended Saif al-Islam Gaddafi on November 19, 2011, in southern Libya and are holding him in the town of Zintan. Although the Libyan government has indicated since January 2012 that it plans to transfer Gaddafi to a detention facility in Tripoli, these efforts appear stalled.

Mauritania extradited Sanussi to Libya on September 5, 2012, where he remains in government custody in Tripoli in the Al-Hadba Corrections Facility. A number of other Gaddafi-era senior officials, including former Prime Minister Al-Baghdadi al-Mahmoudi and the former head of foreign intelligence, Abu Zaid Dorda, are also being held at the Al-Hadba facility.

31. Does Gaddafi have a defense lawyer for proceedings against him in Libya?

Though Gaddafi has met twice with Office of Public Counsel for the Defence (OPCD) lawyers initially appointed to represent him at the ICC, Gaddafi did not have access to a lawyer for any domestic proceedings in Libya apparently until May 2 (see question 33).

Libya had consistently claimed that Gaddafi had not chosen to exercise his right to appoint defense counsel for the main national criminal proceedings against him, and which form the subject of Libya’s admissibility challenge. Further, Libya asserted that if Gaddafi had not retained a lawyer by the time these proceedings entered the accusation phase (a pre-trial stage in Libya during which a judge assesses the reliability and sufficiency of evidence collected by the prosecutor), a defense lawyer would be appointed to represent him, in accordance with Libyan law.

The OPCD contended, however, that Gaddafi had expressed the wish to be represented in these domestic proceedings by a lawyer chosen by his family. The OPCD claimed that during their second meeting with Gaddafi, on June 7, 2012, Libyan authorities confiscated a document that laid out the views of his family and friends on options for his legal representation, among other matters. The OPCD said that Libya’s claim that Gaddafi had declined to appoint a lawyer lacked credibility. Gaddafi’s new lawyer at the ICC has likewise argued that this contention is implausible.

It is unclear whether the Libyan lawyers now apparently representing Gaddafi in a separate matter (see question 33) will also do so for the main national proceedings against Gaddafi related to the ICC’s case.

32. Has Gaddafi been brought before a judge in Libya regarding his detention?

In its admissibility challenge, Libya initially stated that Gaddafi's detention had been extended three times on the authority of the general prosecutor after he received permission from a summary judge, who travelled to Zintan for this purpose, and in conformity with Libyan law.

However, in further submissions filed with the court, Libya later clarified that detention extensions authorized prior to October 30, 2012, were issued solely on the authority of the general prosecutor, without the involvement of a judge. Libya says the People's Courts Procedures had permitted the prosecutor to issue such detention extensions without judicial approval until the Libyan Supreme Court ruled in December 2012 that this practice was unconstitutional. Libya says that ruling did not invalidate previous decisions made under these procedures. Libya claims that all extensions of Gaddafi's detention made after October 2012 have been judicially approved.

The Office of Public Counsel for the Defence (OPCD) argued that Libya's claims on the lawfulness of Gaddafi's detention are not credible given the contradictions in its submissions on this issue. It also disputed the authenticity of the detention orders submitted to the court, and contested Libya’s assertion that the Libyan Supreme Court ruling is not retrospective.

33. Hasn’t Gaddafi already appeared in court in Zintan? What were those proceedings about?

On January 17 and on May 2, Gaddafi appeared in a court in Zintan. According to Libya, his appearance was unrelated to the main criminal proceedings against him, and which form the subject of Libya’s admissibility challenge. Instead, Libya alleges that the court appearance was connected to a separate case involving alleged national security breaches stemming from the Office of Public Counsel for the Defence’s (OPCD) visit to Zintan in June 2012. Libya argues that it is not barred from initiating unrelated proceedings, and that it is therefore not in violation of its obligations to the ICC.

Following Gaddafi's first court appearance in January, the OPCD argued that these proceedings against Gaddafi are based on privileged defense materials unlawfully seized by Libya during the ICC delegation’s visit to Zintan in June 2012, and asked the ICC judges to order Libya return them to the defense. Furthermore, the OPCD says that Libya’s initiation of domestic proceedings against Gaddafi for acts unconnected to the ICC’s charges violates the Rome Statute.

In March, the ICC judges instructed the court’s registrar to ask Libya to return to the defense the original documents seized in Zintan and destroy any copies. In their ruling, the judges noted that the other issues raised by the OPCD could be appropriately addressed in its final decision on Libya's admissibility challenge.

34. Does Sanussi have a defense lawyer for proceedings against him in Libya and has he been brought before a judge?

Sanussi told Human Rights Watch in a prison visit on April 15 that he has not had access to a lawyer or been informed of the formal charges against him during almost eight months in Libyan detention. During the same visit, Sanussi said that he has been taken before a judge about once a month to review his detention. Each time the judge has extended the detention, he said. “During these sessions, I have asked the judge to let me see my family and I have asked for a lawyer,” Sanussi said.

35. Are there international legal standards on detention to which Libya is bound?

Yes. Libya is bound to apply the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, both of which it has ratified.

Notably, the ICCPR states that anyone detained shall be brought promptly before a judge or person exercising judicial power. Failure by the authorities to ensure this leads to arbitrary detention. The right to judicial review of all detainees without delay is non-derogable, or absolute, meaning it is applicable at all times, including during states of emergency.

Furthermore, in its General Comment 32 interpreting article 14 of the ICCPR, the United Nations Human Rights Committee stated that "[i]n cases involving capital punishment, it is axiomatic that the accused must be effectively assisted by a lawyer at all stages of the proceedings," and that "[t]here is also a violation of this provision if the court or other relevant authorities hinder appointed lawyers from fulfilling their task effectively." On March 15, 2013, the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights issued provisional measures ordering Libya, among other things, to allow Gaddafi access to a lawyer of his own choosing.

36. Has Human Rights Watch been granted access to visit the two ICC suspects?

Human Rights Watch visited Gaddafi in Zintan on December 18, 2011. Since then, Human Rights Watch has repeatedly requested permission to visit both Gaddafi and Sanussi. Libya’s justice minister recently granted Human Rights Watch authorization to meet with both detainees. On April 15, Human Rights Watch met with Sanussi without the presence of any guards, seemingly in private, for 30 minutes. Libya said it needed time to make the necessary arrangements for a visit to Gaddafi.

37. What is the status of the domestic proceedings against the two ICC suspects? When are the domestic trials expected to begin?

Libya says that no case can go to trial unless ordered by a pre-trial judge, who assesses the reliability and sufficiency of evidence collected by the prosecutor and determines whether the investigation has been properly conducted.

In its submissions to the ICC, Libya claims that its investigation into Gaddafi is nearly completed. On this basis, Libya said that the case was expected to be transferred for pre-trial proceedings sometime in February 2013, but later clarified that a pre-trial judge would decide the exact time of transfer. Libya also says that Sanussi's case is nearing the pre-trial phase. In Gaddafi's case, Libya estimates that the pre-trial stage would last about three months.

To Human Rights Watch’s knowledge, neither Gaddafi nor Sanussi’s cases have reached the pre-trial stage.

38. Where will the ICC suspects' domestic trials take place in Libya?

Libya reports that the prosecution proposes trying Gaddafi jointly with Sanussi and some other former Gaddafi-era officials in a civilian proceeding. It says that if this proposal is judicially approved at the pre-trial phase, then the trial will take place in Hadba in Tripoli, where Sanussi is detained. If, on the other hand, it is decided that Gaddafi should be tried alone, his trial will take place at the South Tripoli Criminal Court.

39. Who is in charge of the domestic cases against the ICC suspects in Libya?

Libya's general prosecutor, Abdul Qader Juma Radwan, is responsible for the domestic cases against the two accused. Radwan was appointed on March 20, replacing Abdelaziz al-Hasadi.

Libya says that Sanussi's case was previously under the military prosecutor's charge on account of his prior role in the armed forces, but was transferred to civilian jurisdiction based on a decision by Libya's Supreme Court.

40. Does Human Rights Watch believe that the two ICC suspects will receive fair trials in Libya?

Human Rights Watch believes the Libyan judicial system faces significant challenges, particularly the government’s inability to date to gain control over all detainees held in militia run facilities, including Gaddafi. Other challenges including abuse in custody, mainly in militia-run detention facilities; denial of access to lawyers; and lack of judicial reviews weigh heavily on Libya's ability to provide a fair trial for the two suspects. Furthermore, despite some positive steps, the authorities have struggled to establish a functioning military and police force that can enforce and maintain law and order. The resulting fragile security environment raises serious concerns about whether the safety of judicial personnel and others can be guaranteed during these trials, if they proceed.

Trials of serious crimes can be extremely sensitive and create risks to the safety and security of witnesses and victims who may testify to deeply traumatic events. Moreover, judges and prosecutors cannot work independently or impartially if they fear for their safety. The risk of retribution is even greater for judicial personnel involved in cases of serious crimes, given the gravity and sensitive nature of the underlying crimes. In the past year, there were reports of threats and physical attacks on prosecutors and judges in parts of Libya.

41. Libyan law allows for the imposition of the death penalty. How does Human Rights Watch view this punishment?

Human Rights Watch opposes capital punishment in all circumstances because of its inherent cruelty and irreversibility. In addition, it is a form of punishment plagued with arbitrariness, prejudice, and error.

Life imprisonment is the maximum penalty that can be handed down by the International Criminal Court, the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, and the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia. The UN General Assembly adopted a resolution in December 2007 calling for a moratorium on executions with a view to abolishing the death penalty.