Summary

“[The Saudi justice system] is like a web and once you are caught in it, it is difficult to get out.”

—Ghulam, former Pakistani detainee in Saudi Arabia

Saudi officials vigorously defend the country’s criminal justice system when facing criticism by international media outlets, United Nations human rights bodies, and human rights organizations. On August 4, 2017, Saudi Arabia’s Ministry of Justice spokesperson said, “The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia’s courts are independent courts that work—in accordance with the Basic Law of Governance—to apply Islamic law rulings and follow procedural laws that govern the course of trials and provide fair trial guarantees for all defendants.”

The practice of Saudi justice, however, which largely follows interpretations of uncodified Islamic law, does not measure up to such declarations, and over a decade of reforms have not appreciably strengthened the safeguards against arbitrary detention or ill-treatment, or enhanced the ability of Saudi and non-Saudi defendants to obtain fair trials.

The defects in the criminal justice system are especially acute for the twelve million foreigners living in Saudi Arabia, over one-third of the country’s total population, who face substantial challenges obtaining legal assistance and navigating Saudi court procedures. At 1.6 million people, Pakistanis make up the second-largest migrant community in Saudi Arabia, most of whom travel to the country as foreign migrant workers.

This report is based on interviews with twelve Pakistani citizens detained and put on trial in Saudi Arabia in recent years, as well as seven family members of nine other defendants. All interviews took place in Pakistan with the exception of two telephone interviews with Pakistani inmates in Saudi prisons. Researchers interviewed these individuals between November 2015 and September 2016. Interviews were conducted in Urdu and Punjabi. The criminal cases involved 21 total defendants in 19 separate cases that ranged from minor crimes such as petty theft and document forgery to serious offenses, including murder and drug smuggling, which are often capital offenses in Saudi Arabia.

Nearly all the Pakistani detainees, former detainees, and their family members described widespread due process violations by the Saudi criminal justice system and Saudi courts, including long periods of detention without charge or trial, no legal assistance, pressure to sign confessions and accept predetermined prison sentences to avoid prolonged arbitrary detention, and ineffective or pernicious translation services for defendants.

Due process violations were most consequential for defendants involved in serious cases such as drug smuggling and murder. In Saudi Arabia, judges apply a 1987 ruling by the country’s Council of Senior Religious Scholars prescribing the death penalty for any “drug smuggler” who brings drugs into the country, as well as provisions of the 2005 Law on Combatting Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances, which prescribes the death penalty for drug smuggling. The law allows for mitigated sentences in limited circumstances.

Saudi Arabia executes more Pakistanis than any other foreign nationality annually, nearly all for heroin smuggling, including 20 in 2014, 22 in 2015, 7 in 2016, and 17 in 2017.

Of the 21 Pakistanis involved in criminal cases, 15 faced drug-related crimes and authorities charged 11 with bringing in drugs at an international airport. Of the eleven individuals, Saudi courts have given three men death sentences, four individuals had prison sentences ranging between fifteen and twenty years, one had a prison sentence of four years, and three remained on trial. According to family members, drug traffickers in Pakistan forced under threat of violence four of the eleven individuals to serve as “drug mules.” The family members stated that courts were not interested in the circumstances under which individuals brought drugs into the country and did not attempt to investigate or appear to take into account claims of coercion during sentencing.

In all the non-death penalty cases, judges did not afford defendants an adequate opportunity to mount a defense. Interviewees said that during their first court hearings Saudi judges presented them with predetermined convictions and sentences based solely on police reports and asked defendants to accept the rulings and sentences. If they chose to dispute the ruling, the courts permitted defendants to submit a written defense, but nevertheless the courts repeatedly summoned them for additional hearings in which judges presented the same predetermined rulings, leaving detainees with the impression that not accepting sentences would mean indefinite pretrial detention. Five of the Pakistani defendants accepted the rulings during their first court hearing, and all of the others eventually accepted the original rulings merely to halt what they believed would be indefinite pretrial detention and get out of prison as soon as possible. As one detainee stated: “The judge had our case files in front of him. He passed our sentences without listening to our stories.”

Nine of the 21 defendants said that court officials pressured them to give their agreement to court rulings through confessions or stamping the ruling papers with an inked copy of their fingerprints (taken as a sign of consent) without affording them the opportunity to read, review, or fully understand these judgments. One detainee deported in 2014 said that he accepted a conviction on charges of alcohol consumption and fighting after the judge told him verbally that his sentence was 10 days and 80 lashes, which he considered acceptable. He said he was later shocked to discover that the sentence also ordered his deportation, and he said he would have challenged it had he known this. He pleaded with justice officials to take back the decision to no avail.

With one exception, none of the 21 Pakistani defendants in these trials had a defense lawyer largely because they did not have the resources to locate or pay a lawyer while in prison. Largely due to this lack of legal assistance, only the one detainee had possession of court documents or copies of their convictions. Some of the detainees and family members said courts would not provide these documents while others said they did not request them.

Four of the detainees said that court-appointed translators did not provide adequate services, sometimes intentionally misrepresenting detainees’ statements to judges or failing to accurately describe the contents of Arabic-language court documents. Three defendants said that court-appointed translators misrepresented their statements to judges, which they were able to understand having learned limited Arabic living in Saudi Arabia. They said that translators told judges that defendants were pleading for forgiveness while they were actually disputing the charges or conviction.

Seven of the former detainees said that they remained in prison up to eight months following the expiry of their sentences for various reasons, including apparent negligence by prison officials and slow processing of deportation procedures.

In addition to due process violations, some of the Pakistani detainees and their family members described poor prison conditions during their detention, including overcrowding, unsanitary facilities, lack of beds and sheets, as well as poor provision of medical care. One former detainee described his detention experience in the southern province Jazan: “It was overcrowded and the conditions of the prison were deplorable. Often there was no water for days and there was no proper sewage system. The bathrooms were so unhygienic and filthy that we dreaded using them.”

Two former detainees and one current detainee said that Saudi prison authorities had subjected them to ill-treatment, including slapping, beating with a belt, and shocking with an electrical device during interrogations. The family member of another detainee said that authorities had beaten her husband with “sticks” following his detention.

Under the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations, which Saudi Arabia ratified in 1988, it has an obligation to inform Pakistani consular officials when they arrest a Pakistani citizen. Under article 36 of the convention, “…the competent authorities of the receiving State shall, without delay, inform the consular post of the sending State if, within its consular district, a national of that State is arrested or committed to prison or to custody pending trial or is detained in any other manner.” In the cases Justice Project Pakistan and Human Rights Watch reviewed, however, it did not appear that Saudi officials informed Pakistani consular officials about the arrests of the Pakistani citizens, and the burden to inform Pakistani authorities largely fell on detainees and family members. Justice Project Pakistan wrote to Pakistani Ministry of Foreign Affairs officials about all of the Pakistani detainees they learned about but did not receive any response to their inquiries. Furthermore, Justice Project Pakistan researchers said that the family members they interviewed generally did not know which government agency to contact when their relatives were arrested in Saudi Arabia.

Based on interviews conducted with former detainees, current detainees, and family members of detainees, most of the Pakistanis did not seek consular services from the Pakistani embassy in Riyadh or consulate in Jeddah at any point during their detentions because they did not believe Pakistani officials would offer any assistance and they did not want to waste limited money on such phone calls. They said that Pakistani officials rarely if ever visited Saudi prisons, unlike representatives of other countries. Four of the defendants who did contact Pakistani embassy officials said they did not provide any assistance other than deportation processing procedures following prison sentences. Only one of the defendants, who is currently serving a 20-year sentence for drug smuggling, said he met with a Pakistani consular official during his trial.

Saudi Criminal Justice System Background

Human rights organizations and UN human rights bodies have criticized Saudi Arabia’s criminal justice system for many years. The violations of defendants’ rights are so fundamental and systemic that it is hard to reconcile Saudi Arabia’s criminal justice system, such as it is, with a system based on the basic principles of the rule of law and international human rights standards. The violations derive from deficiencies both in Saudi Arabia’s law and practices. Saudi Arabia has not promulgated a penal (criminal) code. Previous court rulings do not bind Saudi judges, and there is little evidence to suggest that judges seek to apply consistency in sentencing for similar crimes. Accordingly, citizens, residents, and visitors have no means of knowing with any precision what acts constitute a criminal offense. The Saudi criminal justice system imposes the death penalty after patently unfair trials in violation of international law and imposes corporal punishment in the form of public flogging, which is inherently cruel and degrading. Saudi law and practice are also inherently discriminatory.

Saudi criminal procedures, which permit judges to shift roles between adjudicator and prosecutor, indicate that in practice there is no presumption of innocence for defendants. Unless the crime is considered “major” under Saudi law, the trial judge dons the mantle of both judge and prosecutor. In all criminal cases, the judge can change the charges against the defendant at any time and, in the absence of a written penal code, it appears that judges in some cases set out to prove that the defendant has engaged in a certain act, which they then classify as a crime, rather than proving that the defendant has committed the elements of a specific crime as set out in law. In other cases, defendants recounted how a judge refused to proceed with a trial unless the defendant disavowed and withdrew a claim that his confession was extracted under torture, effectively holding the defendant hostage until he reaffirmed a confession obtained under duress.

With exceedingly short notice before court hearings, defendants have little time to prepare their defense and often lack access to their files, including the prosecutor’s case against them and the specific charges under Saudi law. Detainees do not always have access to Saudi statutory laws or relevant interpretations of Sharia for the Saudi criminal justice context. Unless they have had specialized Sharia training, they have no means of knowing the elements of the crime pertaining to the criminal behavior they were accused of, the procedures necessary to establish guilt under Sharia rules, and the penalty they could expect to receive if found guilty.

In the case of Pakistanis interviewed for this report, those apprehended at international airports for drug crimes generally had not visited Saudi Arabia before and did not speak or read Arabic. Many of those who had lived for extended periods in Saudi Arabia had learned to speak Arabic, but few had learned to read or understand written Arabic, adding an additional burden to those wishing to understand Saudi legal statutes and prepare a written defense, which defendants must submit in Arabic. In the absence of Saudi lawyers, some Pakistani detainees said that they relied on Arabic-speaking fellow detainees to prepare their written defense documents.

In 2001 Saudi Arabia promulgated the country’s first criminal procedure code, which establishes the legal and court procedures governing criminal cases but does not define crimes or set punishments. The Law of Criminal Procedure (LCP) theoretically guarantees the right to legal representation as well as Arabic translation services for non-Arabic speakers. Article 4 guarantees “the right to seek the assistance” of a lawyer. For non-Arabic speakers, the LCP states that “[i]f the litigants, witnesses or either of them do not understand Arabic, the court must seek the assistance of interpreters” (article 171).

While this was a welcome step, the LCP does not incorporate all international standards pertaining to the basic rights of defendants. For example, the LCP does not permit a detainee to challenge the lawfulness of their detention before a court, it fails to guarantee access to legal counsel in a timely manner, and contains no provision for free legal assistance to those who cannot afford a lawyer. The LCP grants the prosecutor the right to issue arrest warrants and prolong pretrial detention up to six months without any judicial review. While the LCP prohibits torture and undignified treatment, it does not make statements obtained under duress inadmissible in court. It does not set out the principle of presumption of innocence, or protect a defendant’s right not to incriminate themselves. Furthermore, it does not sanction officials who coerce defendants, and empowers prosecutors to detain suspects without having to meet a defined standard of evidence of a suspect’s probable guilt.

Recommendations

To the Government of Saudi Arabia

- Adopt a written penal code in compliance with international standards.

- Enact new and amend existing legislation to reinforce protections against arbitrary arrest, due process, and fair trial violations.

- Instruct prosecutors and judges to dismiss cases or overturn verdicts where serious due process and fair trial violations have occurred.

- Set up a program affording all indigent access to a lawyer.

- Outlaw the death penalty and all forms of corporal punishment in all circumstances, starting with non-serious crimes such as nonviolent drug smuggling.

- Actively investigate claims of coerced drug trafficking and other exploitation.

- Notify the Pakistani Embassy immediately when a Pakistani citizen is arrested or detained pending trial.

- Grant Pakistani officials access to Pakistani citizens in detention.

- Allow adequate time for detainees to prepare their defense, including granting adequate time to Pakistanis accused of drug trafficking to gather evidence from Pakistan indicating that they were coerced.

- Improve Arabic translation services available to Pakistani detainees and ensure that they are communicating the defendants’ words and intentions accurately.

- Consider negotiating a prisoner transfer agreement with Pakistan in light of the high number of Pakistani citizens in Saudi detention.

- Allow for the dead bodies of those executed to be returned home for burial.

- Implement clear and transparent rules governing royal pardons, including an application system available to all detainees without prejudice.

To the Government of Pakistan

- Provide adequate consular services for Pakistani detainees in Saudi Arabia.

- Help ensure that Pakistani detainees in Saudi Arabia have access to legal representation.

- Investigate and prosecute all agencies and individuals involved in forcing Pakistanis traveling to Saudi Arabia as drug mules.

- Educate Pakistani migrant workers about the flaws in Saudi Arabia’s criminal justice system prior to their departure.

Methodology

Access to Saudi Arabia for human rights organizations to freely conduct in-country research has long been highly restricted. Human Rights Watch was granted permission to conduct a research mission in Saudi Arabia in November-December 2006. Human Rights Watch staff have visited Saudi Arabia six times since then, but these visits remained tightly circumscribed.

Saudi Arabia’s record on allowing independent criticism and free expression more broadly has been dismal, particularly over the past decade. Dozens of activists, lawyers, human rights defenders, and journalists have been prosecuted for peaceful dissent. Saudi citizens and foreign workers living in Saudi Arabia are often wary of carrying out extended conversations on human rights issues via telephone or email, fearing government surveillance that is widespread across social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter.

For this report, Justice Project Pakistan researchers interviewed twelve Pakistani citizens detained and put on trial in Saudi Arabia in recent years, as well as seven family members of nine other defendants. All interviews took place in Pakistan apart from two telephone interviews with Pakistani inmates in Saudi prisons. Researchers interviewed these individuals between November 2015 and September 2016. Interviews were conducted in Urdu and Punjabi. The criminal cases involved 21 total defendants in 19 separate cases that ranged from minor crimes such as petty theft and document forgery to serious offenses, including murder and drug smuggling, which are often capital offenses in Saudi Arabia.

Where available, Human Rights Watch and Justice Project Pakistan incorporated government statistics and officials’ statements into this analysis. Researchers informed all participants of the purpose of the interview and the ways in which the data would be used and were given assurances of anonymity. This report uses pseudonyms for all interviewees and withholds other identifying information to protect their privacy and their security. None of the interviewees received financial or other incentives for speaking with Human Rights Watch and Justice Project Pakistan.

On September 9, 2016, Human Rights Watch and Justice Project Pakistan sent a letter to seek information on embassy services provided to Pakistani citizens who face criminal charges in Saudi Arabia. The letter did not receive a response at the time of this writing. Justice Project Pakistan wrote to the Pakistani Ministry of Foreign Affairs urging them to intervene whenever they learned of the detention of a Pakistani detainee but did not receive any responses.

I. Lack of Due Process in Saudi Courts

Justice Project Pakistan interviewed Pakistanis who said that in nearly every stage of the court procedures they or their family members experienced violations of their right to a fair trial.

Inability to Inform Others Following Arrest

Article 36 of Saudi Arabia’s Law on Criminal Procedure grants that any detainee should be “advised of the reasons of his detention and shall be entitled to communicate with any person of his choice to inform him of his arrest.”[1] In practice, however, Saudi authorities did not provide the means or opportunity for Pakistanis to inform others of their arrests in a timely manner.

Ten of the 21 detainees in the 19 cases examined in this report said that Saudi officials held them a week or longer following their arrest without allowing them to contact family members or seek consular services from the Pakistani embassy. Most said that they were only able to contact family members eventually by paying other detainees to use contraband phones smuggled into prisons and detention centers.

Abbas, who served an 11-month sentence in Jeddah’s Buraiman Prison for holding a forged work permit, said he had no contact with his family members until seven days after his arrest. He said, “While I was in the CID [Criminal Investigation Department] detention center, I had no means of contacting my family. When the officials shifted me to the central police station, I took a phone from another cellmate who had it in his possession illegally. I called my family from that phone and informed my brother about my arrest.”[2]

Another former detainee, Ejaz, served a 10-month sentence in Jazan Central Prison for transporting drugs in his taxi. He said that Saudi authorities arrested him in November 2014 at a checkpoint as he was transporting a Saudi man’s luggage from Jeddah to the southern province of Jazan. He said he did not know that the luggage contained drugs. Following his arrest, he said that he had to wait 20 days before he could inform his family members.[3]

I called my family 20 days after my arrest because I didn’t know anyone who could lend me a phone to call my family or friends. I couldn’t meet anyone from the Pakistani embassy either during this time, because they visit jail once in a month [sic]. Also, I didn’t have money to pay for making phone calls from someone’s phone during the first 20 days. After about 18-20 days, I asked a fellow inmate to make a phone call to my family, who allowed me to call.[4]

Another former detainee, Rashid, said that following his drug-related arrest authorities did not allow him to contact his family members for 16 days. When he finally managed to contact his family, he said they were conducting his memorial service, assuming he had died.[5]

Detention Without Charge

Detainees and detainees’ family members said that Saudi authorities held them for long periods, in one case up to eight months, without bringing them before a Saudi judge. Article 117 of Saudi Arabia’s criminal procedure law allows criminal justice authorities to hold detainees in detention for up to six months without seeing a judge, after which they must transfer their case to a competent court.[6] Detentions beyond six months without charge or trial or without an appearance before a judge are arbitrary and violate Saudi law. The six-month detention period allowed by Saudi law itself represents a violation of international standards. Principle 11 of the United Nations Body of Principles for the Protection of All Persons under Any Form of Detention or Imprisonment states that a detainee must be “given an effective opportunity to be heard promptly by a judicial or other authority,” and that a judicial or other authority should be empowered to review the decision to continue detention.[7] The Arab Charter on Human Rights, which Saudi Arabia ratified in 2009, also guarantees the right of anyone arrested or detained on a criminal charge to be brought promptly before a judge or other officer of the law, and to have a trial within a reasonable time or be released. The charter says that, “Pre-trial detention shall in no case be the general rule.”[8]

Human Rights Watch and Justice Pakistan Project analyzed a regularly updated online Saudi Interior Ministry database that purports to list cases of detainees in Saudi detention centers, without identifying them, and the status of their cases. The database, as it appeared on August 30, 2017, showed 83 Pakistanis in Saudi detention.[9] Of the 83, 61 appeared to have remained in detention for periods longer than 6 months without having their cases referred to Saudi courts. Of these sixty-one, fifty were “under investigation,” six had the case status “under processing to move to bureau of investigation,” and five had the status “case at bureau of investigation.” In other words, the data shows that Saudi criminal justice officials appear to have held most detained Pakistani citizens for far longer than the six-month maximum period allowed without referring them to a Saudi court. Saudi officials have held one detainee “under investigation” since his arrest on August 9, 2015, a period of over two years.[10]

Interviews with Pakistani detainees confirmed Saudi Arabia’s practice of holding detainees for long periods without charge. One former detainee, Abbas, said authorities held him in Jeddah’s Buraiman Prison for four-and-a-half months before bringing him before a judge in a case involving a fake work permit.[11] The father of another current detainee, Babar, said his son was detained for drug smuggling when he landed in Saudi Arabia, but authorities did not bring him to a court hearing until eight months later.[12] A third former detainee, Naveed, whose 10-year sentence for drug distribution was commuted when King Salman issued a general amnesty in early 2015 after he became king, said that authorities held him for six months before bringing him to attend his first court hearing, and that his second hearing was one year and three months after the first.[13]

Convictions and Sentences Presented at First Hearing

Nearly all detainees and their family members said that Saudi courts did not give detainees any meaningful opportunity to argue their side of the case before Saudi courts. For all non-serious cases, detainees said that judges did not attempt to establish the facts of a case with input or feedback from Pakistani defendants. Rather, the judge had prepared their convictions and sentences in advance when they attended their first hearing. They said that judges gave detainees an opportunity to contest the rulings by submitting an Arabic-language written defense—often written by hand in prison without legal assistance and with help from other Arabic-speaking detainees—but in no cases did these defense arguments alter the rulings, which were presented again and again before defendants as they attended hearings, unchanged no matter what evidence the defendant tried to present. In all cases, detainees either immediately or eventually accepted their sentences, fearing that continuing to contest the rulings would result in indefinite detention.

One former detainee who served a one-year sentence for attempting to leave Saudi Arabia with a forged passport and arrived in Pakistan in September 2015 following his deportation, described his experience at his first hearing:

The judge asked me to sign a confession letter which was in Arabic. I was given eight months of imprisonment. I was working in [Saudi Arabia] for about three-and-a-half years so I could understand Arabic thus I did not ask for a translator. The judge did not tell me anything apart from my crime. Judges do not usually talk to anyone except for prisoners involved in very serious crimes. He did not talk to me…. I just silently accepted what was written in the letter because I wanted to get over the whole thing quickly. I had seen in the prison that prisoners who refused to sign the letter stay in the jail for a longer time. The judge keeps sending them back to jail every time they refuse; thus, this prolongs their stay in prison. I did not want that to happen with me. Apart from the judge, two other men were present in the room. One was the reader and one was writing something…[14]

Another detainee, Ghulam, described how he eventually accepted his six-month sentence for transporting drugs in his taxi after the judge presented the same option again and again over four separate court hearings:

I was asked to sign a confession letter, which stated that I was transporting the drugs, and I was guilty as the drugs were mine. This letter was presented to me on my first day of trial.... I refused to sign it by stating that I had nothing to do with the drugs and it was not mine so I was not guilty. [Over] two more hearings the judge asked me to sign the confession letter again. I eventually gave in [during] my fourth hearing and signed the confession letter…. I had already received a sentence of six months imprisonment and four months had passed by that time. I thought there is no harm in signing it now as only a little time of my sentence was left.[15]

A third detainee, Kamran, said that he accepted his 10-day sentence for fighting and drinking alcohol during his first hearing because he feared contesting the ruling would only prolong his detention. He said, “I had seen in the prison that prisoners who refused to sign the [document] stay in jail for a longer time, so I signed it at that time. The judge keeps sending them back to jail every time they refuse thus this prolongs their stay in prison. I did not want that to happen with me.”[16]

Naveed said that other prisoners instructed him to accept his sentence as soon as possible: “On reaching the jail the other prisoners told me to confess, as my case was not a big offense. Otherwise, they would keep doing this to me and would not give me a proper sentence. Therefore, it was better to get a sentence as soon as possible.”[17]

No Legal Assistance

Under Saudi Arabia’s Law on Criminal Procedure, a defendant has the “right to seek the assistance of a lawyer or a representative to defend him during the investigation and trial stages.”[18] In addition, the Arab Charter on Human Rights, which Saudi Arabia ratified in 2009, guarantees the right to free lawyers and interpreters.[19] However, in only one of the 19 criminal cases documented by Justice Project Pakistan and Human Rights Watch did the defendant have access to a defense lawyer during part of his criminal case. Saudi Arabia does not have a public defender service nor any state support to lawyers who assist those who cannot afford private lawyers.

In most cases interviewees said that it was difficult to obtain legal representation because, unlike Saudi detainees, they had no access to individuals on the outside who could facilitate contact with a lawyer. In addition, most lacked financial resources. Even individuals facing the death penalty for drug-related offenses did not have legal representation or someone to assist them during the legal process. Likewise, Pakistani defendants without lawyers almost never had access to trial documents or court records.

According to Abbas, “I was not provided with any defense lawyer. There is no arrangement for defense lawyers. The legal personnel submit your story and the police records to the judge who reads it and then decides your case and sentences you accordingly.”[20]

The lack of legal assistance sometimes caused defendants to sign confessions or agree to verdicts which they did not read or review carefully and sometimes directly harmed their interests. For example, Kamran said that he accepted a verdict and sentence of 10 days and 80 lashes without knowing that it also contained a deportation order. Wishing to return to work as soon as possible Kamran agreed not to contest the sentence, only to find out later that he agreed to his own deportation. He said:

Judges do not usually talk to anyone except for prisoners involved in very serious crimes. He did not talk to me much. After that [he] asked me to sign the confession letter in such a hurry that I did not get a chance to read it. I just silently accepted what was written in the letter because I wanted to get over the whole thing quickly. I was thinking that I am given just 10 days of imprisonment and after that I would be released. But when I reached Qatif police station, a policeman who gave me his phone to call my cousin told me that the judge gave deportation orders for me. I was very upset after that. I asked the head of Qatif police station that I want to appear before the judge once more to tell him that I didn’t deserve such a harsh sentence. But the head of police station said that he could not take me.

In another case, Hafiz, the husband of a Pakistani detainee, said that his wife and his sister were accosted by two other women at the airport in Pakistan before flying to Saudi Arabia to perform the Umra religious pilgrimage.[21] He said that the two women said that they were poor and wanted to send medicine to relatives in Saudi Arabia but couldn’t afford to send it. They asked the two women to carry it instead, and they agreed. He said that Saudi authorities detained them at Jeddah’s King Abdulaziz International Airport shortly after their arrival during the summer of 2015 for carrying drugs. He continued:

When they reached at the Jeddah airport, the Saudi police [who] checked their luggage told them that those tablets were not for medication but they were drugs. The police … asked the women police to take the two women to the police station…[22]

Hafiz said that after the women told the true story, police detained them. His wife eventually received a 20-year sentence and his sister remains on trial.

In another case, Rashid, a former Pakistani detainee who served three years of a five-year sentence for transporting drugs in his taxi said that he signed a confession and agreed to his sentence after his Saudi work sponsor pressured him to do so.[23] He said:

I was presented before the judge and he sentenced me to five years of imprisonment. The officials asked me to sign a paper but I refused to do so. Later on, my [Saudi] sponsor came and he asked me to sign the papers because he knew that [the court process] was going to make me spend this much time imprisoned anyway. I do not know whether it was a confession letter or anything else because I was given no time to read it. As I stated everything happened in such a hurry that I do not know what was written on the paper. I learned about my confession [later] when the judge told me about it.[24]

Of all the Pakistani defendants, only one, Younus, managed to obtain a lawyer, who assisted him in reducing a death sentence for drug smuggling to 15 years:

Fortunately, two of my friends, one from Saudi Arabia and another from Syria, hired a lawyer for me for 50 thousand Saudi riyals [(US$13,332)]. He fought my case in court and fortunately, on a third hearing sentence, [the sentence] was commuted to 15 years with a 50 thousand riyal [($13,332)] fine and 1,500 lashes.[25]

As Younus’ case demonstrates, a lack of legal representation likely led to harsher outcomes for Pakistanis in the Saudi criminal justice system. Without lawyers, detainees had limited ability to understand court procedures or obtain court documents, and in many cases signed confessions or agreed to sentences that directly harmed their interests.

Lack of Adequate Translation Services

Former Pakistani detainees and family members of current detainees also said that translation services provided by Saudi courts were poor, and, in some cases, translators intentionally misrepresented what defendants said, sometimes admitting to an offense on behalf of a defendant or apologizing and asking for mercy.

According to Amir, who served a one-year sentence for allegedly stealing scrap metal, the translator misrepresented his side of the story, telling the judge that he admitted to the crime. He said, “the translator played the main role … he told the judge that we had accepted our crime and as a result of that the court giving us a one-year sentence.”[26]

Younus, who eventually obtained a lawyer, also complained about misleading translation during the early stages of his trial. He said:

I realized that the translator gave an incorrect statement before the court that I did not say. The translator was stating before the court that the accused told him that he brought these drugs from Pakistan and he is sorry for his act. At this, I directly addressed the judge in Arabic and told him that the translator was giving a false statement. I also told the judge that I didn’t trust that translator. At this, judge sent me back to jail.

Hafiz said that his wife is currently serving a 20-year sentence for drug smuggling after she signed an Arabic-language court ruling she could not read. He said the translator urged his wife to sign it without revealing that it contained a 20-year sentence, saying only that it contained the story she told the judge. He said she later found out about her sentence from a prison guard.[27]

Remaining in Jail Following Expiry of Sentence

Human Rights Watch has previously documented cases in which Saudi authorities did not release prisoners who had completed their sentences, leaving them in prison for additional months and years. Often these extended arbitrary detentions were the product of bureaucratic mistakes.[28]

Four of the Pakistani former detainees interviewed said that Saudi authorities held them in detention for periods longer than their sentences. Ghulam recounted that he remained in prison for 14 months even though he was serving a six-month sentence:

I was sentenced to six months of imprisonment but I had to spend 14 months in prison. I was unaware of what was going on and had no idea when I would be released. Prison officials are very negligent and often do not regularly review the files of the prisoners so they don’t always find out on time that a prisoner’s punishment has ended. A prisoner maybe subjected to delay in his release because of this. I remember the jail authorities once misplaced the file of a prisoner and by the time they discovered the file the prisoner had spent an extra six months in jail. Only after that did they inform the embassy to deport him. After fourteen months, the authorities shifted me to Jeddah’s Buraiman Prison, where I stayed three to four days before being deported to Karachi.[29]

Amir also said that Saudi authorities held him several months over his one-year sentence for scrap metal theft. He said, “Many people are stuck in jail even after they have served their sentences. We were lucky that we got released from the jail in the end, after spending a few months more than a year.”[30]

No Consular Assistance

In the cases reviewed by Justice Project Pakistan and Human Rights Watch it did not appear that Saudi officials had complied with the obligation to promptly inform Pakistani consular officials about the arrests of the Pakistani citizens, and the burden to inform Pakistani authorities largely fell on detainees and family members. Justice Pakistan Project wrote to Pakistani Ministry of Foreign Affairs officials about all of the Pakistani detainees they learned about, but did not receive any response to their inquiries. Furthermore, Justice Project Pakistan researchers said that the family members they interviewed generally did not know which government agency to contact when their relatives were arrested in Saudi Arabia.

Most of the Pakistanis involved in criminal cases did not seek consular services from the Pakistani embassy in Riyadh or the consulate in Jeddah at any point during their detentions because they did not believe Pakistani officials would offer any assistance, and they did not want to waste limited money on such phone calls. They said that Pakistani officials rarely if ever visited Saudi prisons, unlike representatives of other countries. Four of the defendants who did contact Pakistani embassy officials said they did not provide any assistance other than deportation processing procedures following prison sentences. Only one of the defendants, who is currently serving a 20-year sentence for drug smuggling, said he met with a Pakistani consular official during his trial.

Ejaz, a former detainee, said that he did not believe he could seek assistance from the embassy to file an appeal contesting his six-month sentence for transporting drugs in his car. He said, “Who could I ask for help for the appeals process? Our embassy doesn’t even come to see Pakistani citizens in jail, why would they help us in an appeals process? They just don’t have time.”[31]

Another detainee, Fahad, said, “No one can help you once you are in jail.”[32]

II. Detention Conditions

Current and former Pakistani detainees in Saudi jails and prisons as well as family members of current detainees recounted poor prison conditions ranging from overcrowding, unsanitary conditions, and a lack of adequate healthcare.

Overcrowding and Unsanitary Conditions

Former Pakistani inmates said that during their detentions at various detention facilities they experienced overcrowding and unsanitary conditions.

Ghulam described his experience in Jeddah’s Buraiman Prison:

It was overcrowded and the conditions of the prison were deplorable. Often there was no availability of water for days and there was no proper sewerage system. The bathrooms were so unhygienic and filthy that we dreaded using them. There was no access to sunlight and prisoners developed different diseases, especially skin-related. Many prisoners had fallen into depression because of stress.[33]

According to Ejaz, the detention facility in Jazan province where he served his sentence was extremely overcrowded. He said that the facility had a capacity for 200-250 detainees, but actually contained closer to 500. He also said that he had to share a bed with other prisoners, taking turns sleeping. This forced some detainees to have to stay awake at night and sleep during the day.[34]

Fahad recounted a similar experience during his time at a detention facility in Jeddah: “Prisoners slept on the floor and had no blankets. Many used to rip apart the mattress covers and used it as a blanket. The prison cell was almost four marlas [approximately 100 square meters] large and contained around 100 prisoners.” He also said that many prisoners he saw were suffering from skin diseases because of poor hygiene.[35]

Abbas described the small cell authorities held him for six days following his arrest for holding a fake work permit:

The cell was very tiny, almost the size of a small bed and had an attached bathroom which had no door. There was an air conditioner right in front of my cell, due to which I felt very cold, but the officers never turned it off. I did not have any blankets or bed and also, there was no water available in the cell. The officer on duty in the morning had a very pleasant personality and on request, he used to give me a small water bottle that I had to use for the whole day.[36]

Another former detainee, Kamran, recounted the poor conditions while in detention at Qatif Prison:

The room was very small with a dirty [toilet area] inside the room. They gave me one blanket and a pillow to sleep in that room. The room was so dirty that I couldn’t sleep for more than four hours in three days. After three days, the prison police shaved my head and transferred me to the first floor of the jail.[37]

Torture and Ill-Treatment

Four of the 21 current and former detainees whose cases are documented in this report recounted that they experienced torture or ill-treatment at the hands of Saudi authorities. Two former detainees and one current detainee said that authorities tortured them during interrogations in order to obtain confessions. The family member of another detainee said that her husband told her that authorities had beaten him with sticks after arresting him on drug smuggling charges. She said, “He had been detained for 16 days and during those days he was badly tortured. The Saudi police beat him with sticks.”[38]

One former detainee, Ghulam, recounted his interrogation:

The police officials asked me who I worked for, how long had it been, how many times have I smuggled drugs before and other such questions. During one of these interrogations they beat me with a belt and a wire too. This beating was not very severe but lasted for almost 30 minutes.[39]

Murtaza said that authorities had shocked him with an electrical device during his interrogation:

Out of these thirty-five days, I was interrogated more than twenty times, and the interrogation was carried out by one investigator and two translators. They asked me about my syndicate and the people I was working for. I told them my story and how I was forced to supply drugs. They tortured me, gave electric shocks which made my mental condition worse.[40]

Lack of Adequate Medical Care

Former Pakistani detainees also complained that medical care was woefully inadequate in Saudi prisons and detention facilities. Three said that they witnessed other detainees develop skin problems because of poor hygiene and unclean conditions, and that these detainees did not receive any medical treatment.[41]

Abbas stated, “The jail authorities don’t care if someone is sick, unless the person is close to dying…. I fell sick in jail one time and I was not given medicine by the authorities even though I told an official about my condition.”[42]

Ejaz echoed a similar point, stating, “prison officials take prisoners to the hospital only when they realize that someone is going to die.”[43]

Ghulam said that he saw an inmate die in Jeddah’s Buraiman Prison following a fight because no one came to offer him medical assistance:

[A] man of African origin once intervened in a fight between two cellmates and got badly injured. No one came to his aid and he died. After three to four hours when he had died his body was removed from the cell.[44]

Another former detainee, Kamran, said that he fell ill for a week while in detention in Jazan, but prison officials did not give him any medicine. He said that he finally received medicine from a fellow inmate.[45]

Iqbal, the son of a current detainee said that his father, whom Saudi authorities detained over sleeping pills and pain killers he carried with him to Saudi Arabia to treat complications from a broken leg, had not received medicine regularly from prison officials. He said, “[My father] is having a hard time. His old age demands that he should have some sort of assistance, but no arrangements have been made. His cellmates take care of him.”[46]

Pakistani detainees said they were at a disadvantage vis-à-vis Saudi prisoners and others regarding medical care, because they did not receive many visitors who could alert Saudi authorities to urgent medical conditions or bring medication to relatives in prison.

III. Drug-Related Cases

Rampant due process violations in the Saudi criminal justice system carried the gravest consequences for individuals facing drug charges, especially for cases in which Saudi authorities accuse individuals of crossing an international land border with drugs or attempting to bring drugs in through an international airport.

Drug Executions in Saudi Arabia

In contravention of international human rights standards, which only allow for capital punishment for the “most serious crimes,” Saudi Arabia regularly executes individuals for nonviolent drug crimes. Since the beginning of 2014, Saudi authorities have executed 163 individuals for drug crimes, including 61 Pakistanis.[47] Saudi authorities execute more Pakistani citizens annually than any other foreign nationality, most for heroin smuggling.

Drug smuggling executions are tied to a 1987 decision by the Saudi Arabia’s Council of Senior Religious Scholars prescribing the death penalty for any “drug smuggler” who brings drugs into the country.[48] The ruling states, “Regarding the smuggler of drugs, his punishment is death, for the smuggling of drugs and bringing them into the country causes great corruption not limited to the smuggler himself as well as serious damage and great danger to the nation as a whole.”[49] The 2005 Law on Combatting Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances prescribes the death penalty for drug smuggling, but the law allows for mitigated sentences in limited circumstances.[50]

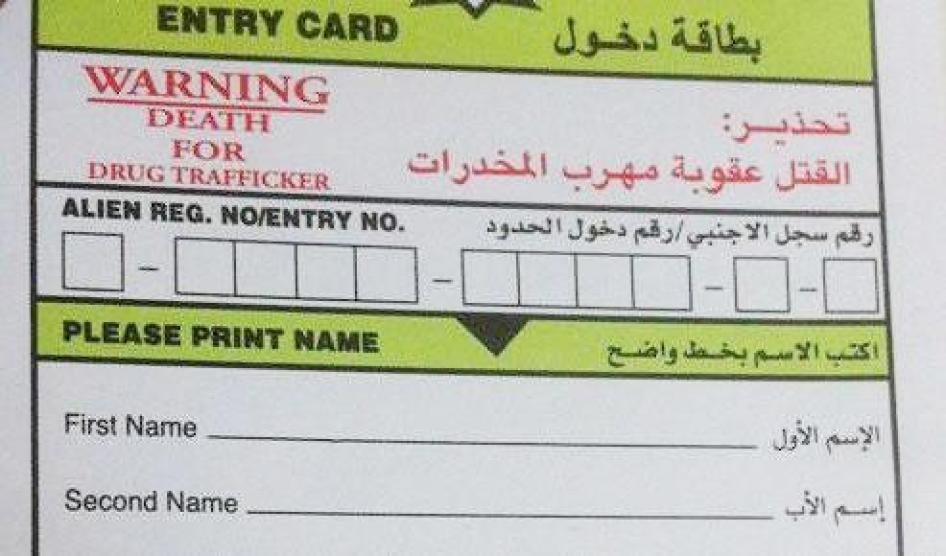

Saudi landing cards state in bold letters “Warning: Death for Drug Traffickers.”[51]

Treatment of those alleged to be carrying drugs at borders contrasts sharply with those caught possessing or transporting drugs internally. Of the thirteen drug-related cases involving Pakistani detainees, those caught transporting drugs inside the country received sentences of between six months to ten years, while those caught bringing drugs from outside the country received the death penalty or sentences of four years or more.

For example, Iqbal, the son of another defendant, said that Saudi authorities apprehended his father for drug smuggling at Jeddah’s King Abdulaziz International Airport in 2016 because he carried with him pain killers and sleeping pills he used to treat himself for complications from a broken leg in 2013. A court eventually sentenced him to four years in prison.[52]

Drug-Trafficking Involving Pakistani Citizens

According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime country profile for Pakistan, “[p]rominent transnational criminal industries operating from, in and through Pakistan include drug trafficking, precursor trafficking, arms smuggling, human trafficking and migrant smuggling. Despite efforts to curb criminal activity, increasingly high volumes of trade and traffic, coupled with potential corruption, facilitate the movement of contraband and allow exploitation by criminal groups.”[53]

Among the 19 criminal cases involving 21 Pakistani individuals documented for this report by Justice Project Pakistan and Human Rights Watch 13 were drug-related cases involving 15 individuals. Authorities charged 11 of these individuals with bringing in drugs at an international airport. Of the eleven individuals, Saudi courts handed three men death sentences, four individuals had prison sentences ranging between fifteen and twenty years, one had a prison sentence of four years, and three remained on trial. According to family members, four of the 11 were forced under threat of violence by drug traffickers in Pakistan to serve as drug mules. The family members stated that courts were not interested in the circumstances under which individuals brought drugs into the country and did not attempt to investigate or appear to consider trafficking claims during sentencing as exculpatory evidence.[54]

In several cases, detainees and family members alleged that men involved in the recruiting firms that sent Pakistanis to Saudi Arabia forced them to traffic drugs to Saudi Arabia.[55]

One Pakistani whom Saudi authorities executed on October 18, 2017 based on a heroin smuggling conviction, said by phone from Dammam Prison in December 2015 that a group of men affiliated with the agency through which he obtained his visa entered his Karachi hotel room prior to his departure to Saudi Arabia and forced him to swallow heroin capsules, beating him with guns and threatening to kill him and his family if he did not comply. He said he was too fearful to report this to Pakistani authorities before he left: “I got the feeling [the drug traffickers] might have someone working for them at the airport, too. I was scared that if I informed any authorities about what I was being made to do, the people would harm me or my family.” Saudi authorities apprehended him in February 2011 when he landed at Dammam’s King Fahd International Airport. He said that a court convicted him after four court hearings, and he did not dispute a 15-year sentence handed down by a Saudi judge because it was better than the death penalty. Later, however, officials informed him that an appeals court had increased his sentence to the death penalty.[56]

Another current detainee serving a 20-year sentence for drug smuggling, Murtaza, recounted his experience by phone from prison:

I just remember that when I was sent to [Saudi Arabia] by [an agent that] had injected me with something and I was not in my right mind. When I reached Dammam airport, I don’t know but somehow I ended up in the wrong line and staff asked me who I was and why I was standing there. They realized that I was not cognizant and took me to scanning room, where they found [the drugs] in my stomach. They kept asking me about that object inside me and I had no answer. I was shut in a small room for 10 days and I didn’t know when they took that object out of me.[57]

Murtaza said that Saudi authorities did not attempt to investigate his claim that he smuggled drugs involuntarily.

Babar, the father of another Pakistani detainee currently on death row for drug smuggling, said that his son spoke to him by phone from Riyadh’s Malaz Prison, telling him that men affiliated with the agency that obtained a visa for him to enter Saudi Arabia held him at a hotel in Karachi prior to his trip and forced him to swallow drug capsules. He said the men kept him under observation the entire flight. He said that Saudi authorities detained his son immediately upon landing and sentenced him to death within two months.[58]

Acknowledgements

This report was researched and written by Adam Coogle, Middle East researcher for Human Rights Watch’s Middle East and North Africa Division, based on interviews conducted by researchers with Justice Project Pakistan.

Justice Project Pakistan would like to thank the families of prisoners and prisoners who were willing to be interviewed and provide vital information pertaining to Pakistani prisoners in Saudi prisons.

Justice Project Pakistan would also like to thank senior investigator Sohail Yaffat, Saqib Mushtaq, and other investigators on the team who travelled throughout Pakistan to locate people mentioned in the report and document their stories.