Summary

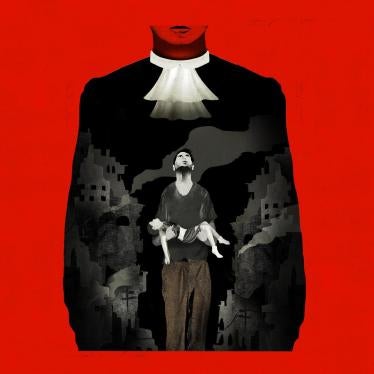

These cases are important. We need to know that these trials are happening because these are the crimes we are fleeing. —Hassan, Syrian refugee in Germany, February 2017

Over the last six years the Syrian crisis has claimed the lives of an estimated 475,000 people as of July 2017, according to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights. All sides to the conflict have committed serious crimes under international law amid a climate of impunity.

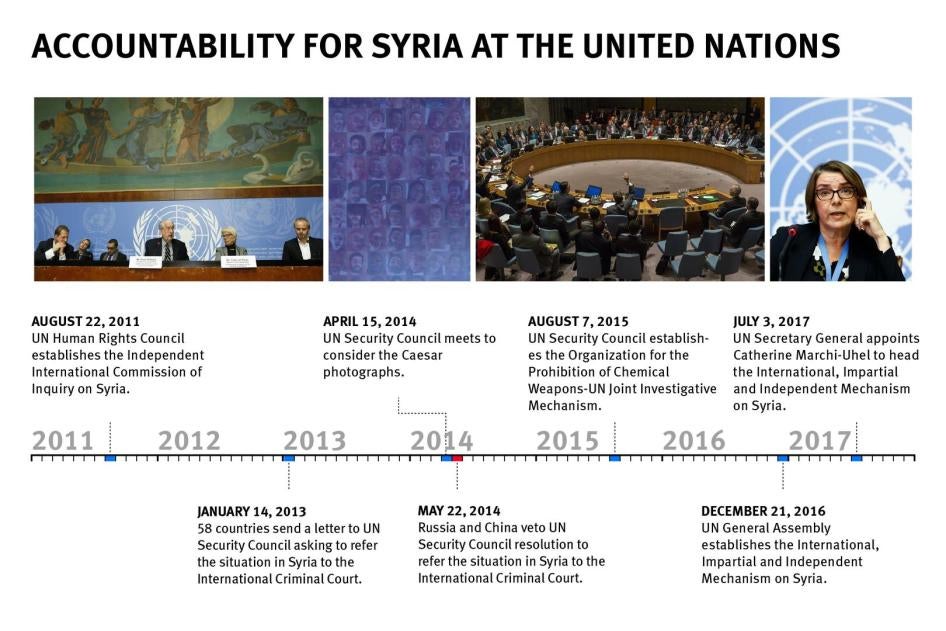

A range of groups have actively documented violations of human rights and humanitarian law in Syria. In late 2016, the United Nations General Assembly also created a mechanism tasked with analyzing and collecting evidence of serious crimes committed in Syria suitable for use in future proceedings before any court or tribunal that may have a mandate over these crimes.

But for the most part, the wealth of information and materials available has not helped to progress international efforts to achieve justice for past and ongoing serious international crimes in the country. Syria is not a party to the International Criminal Court, so unless Syria accepts the court’s jurisdiction voluntarily, the court’s prosecutor needs the United Nations Security Council to refer the situation in Syria to her in order to open an investigation there. However, in 2014, Russia and China vetoed a Security Council resolution that would have given the prosecutor such a mandate. And neither Syrian authorities nor other parties to the conflict have taken any steps to ensure credible accountability in Syria or abroad, fueling further atrocities.

Against this background, efforts by various authorities in Europe to investigate, and, where possible, prosecute serious international crimes committed in Syria, may provide a limited measure of justice while other avenues remain blocked.

The principle of “universal jurisdiction” allows national prosecutors to pursue individuals believed to be responsible for certain grave international crimes such as torture, war crimes, and crimes against humanity, even though they were committed elsewhere and neither the accused nor the victims are nationals of the country.

Such prosecutions are an increasingly important part of international efforts to hold perpetrators of atrocities accountable, provide justice to victims who have nowhere else to turn, deter future crimes, and help ensure that countries do not become safe havens for human rights abusers.

This report outlines ongoing efforts in Sweden and Germany to investigate and prosecute individuals implicated in such crimes in Syria.

Drawing on interviews with relevant authorities and 45 Syrian refugees living in these countries, the report highlights challenges that German and Swedish authorities face in taking up these types of cases, and the experience of refugees and asylum seekers in interacting with the authorities and pursuing justice. In so doing, this report draws valuable lessons for the countries involved and other countries considering investigations involving grave abuses committed in Syria.

The report finds that both countries have several elements in place to allow for the successful investigation and prosecution of grave crimes in Syria—above all comprehensive legal frameworks, well-functioning specialized war crimes units, and previous experience with the prosecution of such crimes. In addition, due to the large numbers of Syrian asylum seekers and refugees in Europe, previously unavailable victims, witnesses, material evidence, and even some suspects are now within the reach of the authorities. As the two largest destination countries for Syrian asylum seekers in Europe, Germany and Sweden were the first countries in which individuals were tried and convicted for serious international crimes in Syria.

Nonetheless, both countries have faced difficulties in their efforts. On one hand, authorities pursuing cases on the basis of universal jurisdiction encounter challenges that are inherent to these types of cases, and solutions to some of these challenges are beyond the reach of authorities. For example, these cases are usually brought against people present in the territory of the prosecuting country and authorities cannot control whether or not certain individuals will travel to their country at a specific time.

On the other hand, the standard challenges associated with pursuing universal jurisdiction cases are compounded, in the case of Syria, by an ongoing conflict in which there is no access to crime scenes. As a result, authorities in both countries have been compelled to turn elsewhere for information, including from Syrian asylum seekers and refugees, counterparts in other European countries, UN entities, and nongovernmental groups involved in documenting atrocities in Syria.

According to practitioners and refugees Human Rights Watch interviewed in Sweden and Germany, gathering relevant information from Syrian refugees and asylum seekers has proved difficult due to their fear of possible retribution against loved ones back home, mistrust of police and government officials based on negative experiences with Syrian authority figures, and feelings of abandonment by host countries and the international community. “Our disappointment is not from the regime, we know the regime, we survived the regime,” one Syrian activist told Human Rights Watch. “Our disappointment is with the world. They use human rights when they need it.”

The report also documents a lack of awareness among Syrian asylum seekers and refugees in Sweden and Germany about the systems in place for the investigation and prosecution of grave crimes, the possibility of their contributing to domestic justice efforts, or the right of victims to participate in criminal proceedings. Most Syrian refugees interviewed were either unaware of ongoing and completed proceedings related to Syria, or had limited or inaccurate information about the cases. Others had unrealistic expectations about what national authorities could deliver by way of accountability given different constraints they face.

Recognizing these issues, authorities in both countries are working to address some of them through various outreach efforts, although more needs to be done and limited resources and mandates constrain efficacy. In addition, authorities need to balance facilitating contact, input and information sharing with potential victims and witnesses with confidentiality requirements inherent in criminal investigations, the risk of being overwhelmed with potentially vast amount of information, and managing expectations of what they will be able to deliver and when to victim communities and the public at large.

Authorities in Sweden and Germany reported that the existence of efficient protocols at the European level has led to good cooperation related to Syria cases, but said they have had limited or no contact with countries neighboring Syria. They have also started to reach out to nongovernmental and intergovernmental actors, including the UN Independent International Commission of Inquiry on Syria, although authorities said that cooperation was slow and that, because of their different mandates, the information collected by these entities while useful at the investigation stage might not meet domestic thresholds for admissible evidence in criminal proceedings.

While any credible criminal proceedings that lead to accountability for crimes committed during the conflict are welcome, the reality is that the initial few cases authorities have been able to successfully prosecute within their jurisdictions are not representative of the scale or nature of the abuses committed in Syria.

The few cases to reach trial have mostly implicated low-level members of ISIS, Jabhat al-Nusra, and non-state armed groups opposed to the government while only one has addressed alleged crimes committed by a low-level member of the Syrian army. In Germany, practical and jurisdictional limitations, such as difficulties finding evidence linking alleged perpetrators to underlying crimes, have also made it easier to bring terrorism charges rather than prosecute for war crimes or crimes against humanity. Terrorism offenses are easier to prosecute because authorities only have to prove connection between the accused and a labeled terrorist organization. However, terrorism charges do not reflect the extent of crimes committed.

Terrorism prosecutions, or prosecutions of low-ranking members of armed groups, should not substitute for efforts to successfully prosecute grave crimes committed by senior officers that are likely to more directly promote compliance with international humanitarian law and ensure justice for grave crimes.

There is also the problem of perception. The use of terrorism charges without significant efforts to pursue prosecutions for war crimes or crimes against humanity, where there is indication that such international crimes were committed, could send the message that the authorities’ only focus is to combat domestic threats. Efforts to pursue terrorism charges can and should go hand in hand with efforts and resources to investigate and prosecute war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide.

Syrian refugees interviewed by Human Rights Watch in both countries expressed frustration that cases prosecuted to date reflect neither the full spectrum of the perpetrators nor of the atrocities committed in Syria. In particular, they said, the lack of cases brought against individuals affiliated with the Syrian government led them to question the balance and fairness of the proceedings overall.

In order to address some of the challenges authorities are facing, Sweden and Germany should ensure that their war crimes units are adequately resourced and staffed, provide them with ongoing training, and consider new ways to better engage with Syrian refugees and asylum seekers on their territory.

Overall, the limited nature of the proceedings to date highlights the need for a more comprehensive justice process to address the ongoing impunity in Syria, and means to engage as many jurisdictions as possible where fair and credible trials can be pursued. A number of potential perpetrators, including high-level officials or senior military commanders affiliated with the Syrian government, are unlikely to travel to Europe. To fill this gap, a multi-tiered, cross-cutting approach will be needed in the long-term which, in addition to proceedings under universal jurisdiction, should include other judicial mechanisms at the international and national level.

Recommendations

To Sweden and Germany

- Ensure that specialized war crimes units within law enforcement and prosecution services are adequately resourced and staffed, including by providing the war crimes units within law enforcement with Syria experts, information technology analysts, forensic analysts, and in-house translators. In the case of Germany, provide the war crimes unit within law enforcement with additional funds and personnel to enable it to filter the information it receives from different sources in relation to grave crimes committed in Syria.

- Provide adequate ongoing training for war crimes unit practitioners, judges, and defense and victims’ lawyers, in issues such as interviewing traumatized witnesses and assessing witness protection needs.

- Consistent with fair trial standards, explore options to enhance protective measures available to witnesses in proceedings related to grave international crimes where necessary to protect witness’ families in other countries.

- Inform asylum seekers who may have been victims or witnesses of grave international crimes that they have the right to report these crimes to the police and to participate in criminal proceedings, including information about the process for doing so. Consider using all appropriate channels of communication for this purpose, including videos and social media.

- Ensure that information provided by individuals in asylum interviews is not shared with law enforcement or prosecution entities without the express informed consent of those individuals, and guarantee as a matter of law that decisions about their refugee status are not contingent on cooperation with law enforcement and prosecutorial authorities.

- Make torture a standalone criminal offense in line with article 1 of the UN Convention Against Torture.

- When there is sufficient evidence to link a suspect to war crimes, crimes against humanity, or genocide, do not limit charges to terrorism offenses.

- Translate important decisions, judgments, press releases, and relevant websites with information on the cases involving crimes in Syria into appropriate languages, such as Arabic and English.

- Consider providing information in appropriate languages, including Arabic and English, on law enforcement and prosecution services websites, electronic applications, and any other similar means used to communicate with the general public on how victims or witnesses of grave international crimes can contact the specialized war crimes units.

- Consider publicizing relevant press conferences and events in which the war crimes units discuss their work within the Syrian community.

- Ensure war crimes units and immigration authorities conduct outreach regarding their mandate to Syrian refugees, asylum seekers, and the broader public in multiple languages including Arabic and English. Consider utilizing social networking platforms to better engage with Syrian refugees and asylum seekers and popularize the work of the units.

- Ensure authorities adequately advertise or distribute the tools they already have available as part of their outreach efforts, including electronic applications, web pages, and brochures.

- Ensure immigration case workers and interpreters employed to assist during asylum interviews are properly trained.

- Ensure that authorities do not use immigration powers to remove persons suspected of serious international crimes instead of prosecuting them, where there is sufficient evidence to do so.

- Continue to provide political and financial support to the International, Impartial and Independent Mechanism on Syria.

To Other Countries Considering Serious Crimes Investigations on Syria

- Establish specialized war crime units within law enforcement and prosecution services where they do not already exist, and ensure they are adequately resourced.

- Establish an adequate legal framework for prosecuting international crimes where one is not in place.

- Ensure effective and meaningful collaboration between the specialized units, including through convening of regular meetings to discuss specific cases.

- Establish a clear and transparent framework for cooperation between immigration authorities and war crimes units that allows for information sharing while protecting the asylum seekers’ rights, including confidentiality.

- Provide adequate ongoing training for war crimes unit practitioners, judges and defense and victims’ lawyers, such as training in interviewing traumatized witnesses and assessing witness protection needs.

- When there is sufficient evidence to link a suspect to war crimes, crimes against humanity, or genocide, do not limit charges to terrorism offenses.

- Refrain from deporting individuals who have been excluded from refugee status without determining that their removal would expose them to a real risk of torture, unfair trials, or other improper or inhuman treatment.

To the European Union

- Provide the EU Genocide Network and Eurojust with adequate resources to carry out their mandate and provide support to member states, including to continue with the organization of ad hoc meetings, to assist countries without specialized war crimes units, and to facilitate regular briefings at the European Parliament.

- Ensure authorities use information shared through the new EASO Exclusion Network to prosecute or extradite for prosecution elsewhere persons suspected of serious international crimes where there is sufficient evidence rather than deporting them. Ensure that no one, irrespective of 1F status, is deported or extradited to a country where they would face a real risk of torture, unfair trial, or other improper or inhuman treatment.

- Establish a central database for war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide within Europol and ensure Europol has adequate analytical support.

To the UN Commission of Inquiry on Syria

- Continue cooperation with domestic authorities engaged in the investigation and prosecution of grave crimes committed in Syria, including by maintaining existing lines of communication.

- Cooperate with the International, Impartial and Independent Mechanism on Syria to ensure complementarity and avoid duplication in the work of the two entities.

To the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights and UN Member States

- Continue cooperation with domestic authorities engaged in the investigation and prosecution of grave crimes committed in Syria, including by maintaining existing lines of communication.

- Cooperate with the International, Impartial and Independent Mechanism on Syria to ensure complementarity and avoid duplication in the work of the two entities.

- Ensure the Commission of Inquiry on Syria is adequately resourced and staffed through the UN Advisory Committee on Administrative and Budgetary Questions (ACABQ) process, including by dedicating personnel to the Commission’s work on cooperation with domestic authorities engaged in the investigation and prosecution of grave crimes committed in Syria and providing access to appropriate software and other tools to assist in such cooperation.

To the International, Impartial and Independent Mechanism on Syria

- Cooperate with domestic authorities engaged in the investigation and prosecution of grave crimes committed in Syria, including by establishing an ongoing dialogue with domestic authorities.

- Coordinate and cooperate with the Commission of Inquiry on Syria to ensure complementarity and avoid duplication in the work of the two entities.

Methodology

This report is based on desk research conducted between October 2016 and July 2017 and field research conducted in Sweden and Germany in January and February 2017, respectively.

Human Rights Watch chose to focus on Sweden and Germany because they have received the largest number of asylum applications from Syrians since 2011 and were the first two countries in which trials related to grave crimes in Syria were completed. In addition, both countries have functioning specialized war crimes units within their law enforcement and prosecution services.

This report focuses on cases pursued by Swedish and German authorities under the principle of “universal jurisdiction.” However, two Syria-related cases in Germany also included in this report were brought under the “active personality principle,” another form of jurisdiction that a state’s judicial system may enjoy if the alleged perpetrator is a citizen of the prosecuting country.

While a range of different actors are involved in these cases—including defense and victims’ lawyers—Human Rights Watch’s research focused on the work of law enforcement and prosecutorial authorities.

In this report, the terms “serious international crimes” and “grave international crimes” are used interchangeably to refer to war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide.

Human Rights Watch conducted interviews with 50 individuals in Sweden, Germany, Switzerland, the Netherlands, and Turkey, including prosecutors, police investigators, analysts, immigration officials, victims’ and defense lawyers, government officials, academics, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), international and European organizations, and journalists. A Human Rights Watch researcher also observed a hearing in the trial against Haisam Omar Sakhanh in the Stockholm District Court in Sweden on January 18, 2017.

Most interviews with officials and experts were conducted in person, but several took place by phone or over email. Nearly all were conducted in English, but three took place in German with an interpreter’s assistance. Many individuals wanted to speak candidly but did not wish to be cited by name or otherwise identified. As a result, information has been withheld that could be used to identify them. The term “practitioner” is used in this report to ensure that sources are not inadvertently revealed; the term variously refers to prosecutors, police investigators, analysts, immigration officials, and lawyers involved in serious international crimes proceedings.

In addition, Human Rights Watch interviewed 45 Syrian refugees between 17 and 58 years old; 10 women and 35 men from different parts of Syria. Ten interviewees were human rights activists. Human Rights Watch interviewed 19 refugees in Sweden (9 in Värmdö, 9 in Varberg, and one over the phone), and 26 in Germany (12 in Berlin, 9 in Hannover and 5 in Cologne). In Sweden, 2 refugees were interviewed individually (including one over the telephone), while 17 were interviewed in small focus groups comprised of four to five persons. In Germany, 8 refugees were interviewed individually, while 18 were interviewed in small focus groups comprised of two to five persons. Twenty-two of the Syrian refugees said they had been detained by the Syrian government; 16 told Human Rights Watch they had been tortured by government forces. Most of these interviews were conducted in Arabic with the assistance of an interpreter, but 9 took place in English. All of the names of the Syrian refugees interviewed have been withheld to protect their identities, and they are instead referred to using pseudonyms.

All interviewees were informed of the purpose of the interviews and the ways in which data would be collected and used, and voluntarily agreed to participate.

I.Background

Individuals from the various armed groups and sides of the Syrian conflict have committed serious violations of international human rights and humanitarian law.

Since 2011, more than 106,000 people have been detained or disappeared, most of them by government forces, including 4,557 between January and June 2016 alone, according to the Syrian Network for Human Rights.[1] Torture and ill-treatment are rampant in government detention facilities, where thousands have died. The Syrian-Russian coalition has carried out airstrikes targeting or indiscriminately striking civilian areas and Syrian government forces have used cluster, incendiary, and chemical weapons in widespread and systematic attacks, in some cases directed against civilians. The Syrian government and pro-government forces have committed further widespread abuses, including unlawfully blocking humanitarian aid, imposing unlawful sieges, extrajudicial executions, and forced displacement.[2]

The Islamic State (also known as ISIS), and the former Al-Qaeda affiliate in Syria, Jabhat al-Nusra (later known as Jabhat Fateh al-Sham, and then Hayat Tahrir al-Sham), are also responsible for systematic and widespread violations, including targeting civilians with artillery, kidnappings, and executions. ISIS and Jabhat al-Nusra have imposed strict and discriminatory rules on women and girls and have actively recruited child soldiers. ISIS has sexually enslaved and abused Yezidi women and girls, used civilians as human shields, and planted victim activated antipersonnel mines in and around territory they have lost, maiming and killing civilians attempting to flee or return home. ISIS has also committed at least three documented attacks against civilians using chemical weapons.[3]

Non-state armed groups opposing the government have also attacked civilians indiscriminately, used child soldiers, engaged in kidnap and torture, unlawfully blocked humanitarian aid, and imposed unlawful sieges.[4]

The United States has supported forces on the ground, including the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF)—comprised of the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG) and other groups. The SDF, YPG and the local Kurdish police, the Asayish, have committed abuses, including the use of child soldiers, arbitrary detention and mistreatment of detainees, alleged disappearances and killings of individuals politically opposed to the Democratic Union Party, and endangered civilians by positioning forces in populated civilian areas.[5]

Both the US-led coalition and Turkish forces were responsible for possibly unlawful airstrikes that caused civilian casualties.[6]

Human Rights Watch has concluded that many of these abuses committed by individuals from all parties since the beginning of the Syrian crisis may amount to war crimes and in some cases crimes against humanity.

In August 2013, a military defector code-named “Caesar” smuggled 53,275 photos out of Syria, many showing the bodies of detainees who died in detention centers.[7] The outrage generated by the images among some Security Council Members prompted France to table a UN Security Council resolution that would have given the International Criminal Court (ICC) a mandate over serious international crimes committed in Syria since 2011. But on May 22, 2014 Russia and China vetoed the resolution, preventing the court’s involvement.[8]

Because Syria is not a party to the Rome Statute, the treaty that established the ICC, the court can only obtain jurisdiction over crimes there if the Security Council refers the situation in Syria to the court’s prosecutor or if Syria voluntarily accepts the court’s authority.[9] Neither is currently a realistic prospect.

The ICC resolution’s defeat means that most avenues toward achieving criminal accountability remain blocked, whether through an international tribunal or at the national level in Syria. The lack of accountability that has resulted has undoubtedly contributed to further grave abuses by all sides to the conflict. At the same time, support for the resolution from many governments and NGOs reflected the widespread international desire to see justice for serious international crimes in Syria.

Documenting Abuses

In response to the Security Council deadlock on Syria, the General Assembly adopted a resolution in 2016 that established an unprecedented mechanism to assist in the investigation of serious international crimes committed there since 2011.[10]

In addition, a range of entities have actively documented violations of human rights and humanitarian law in Syria over the last six years. In 2015, the Security Council established the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons-United Nations Joint Investigative Mechanism (JIM) to investigate the use of chemical weapons in Syria and to attribute responsibility for any attacks.[11] Since then, the JIM has published five reports and has named the Syrian government and ISIS as responsible for chemical attacks in Syria.[12] The Independent International Commission of Inquiry on Syria, established by the UN Human Rights Council in August 2011, has published 22 in-depth reports on grave violations by all sides (14 mandated and 8 thematic reports).[13] Multiple organizations such as Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, the Syria Justice and Accountability Centre, the Commission for International Justice and Accountability, and various local Syrian groups are also involved in different kinds of initiatives aimed at documenting serious crimes in Syria.[14]

Documentation efforts, including preserving potential evidence, will continue to be important and could be vital to future domestic and international accountability processes. At the same time, a judicial forum is still needed for the comprehensive prosecution of perpetrators of serious international crimes in Syria.

National Prosecutions in Foreign Courts

Typically, national authorities are only able to investigate a crime if there is a link between their country and the crime. The normal linkage is territorial meaning that the crime, or a significant element of it, was committed on the territory of the country wishing to exercise jurisdiction (territorial jurisdiction principle). Many states also prosecute on the basis of the personality, meaning that the alleged perpetrator is a citizen of that country (active personality principle), or the victim of the crime is a citizen (passive personality principle). However, some national courts have been granted the jurisdiction to act even if there is no territorial or personality link. This principle—universal jurisdiction—can normally only be invoked to prosecute a limited number of international crimes, including war crimes, crimes against humanity, torture, genocide, piracy, attacks on UN personnel, and enforced disappearances.

Using the principle of universal jurisdiction, several countries have ensured their domestic laws are broad enough to allow law enforcement to pursue individuals in their countries believed to be responsible for certain grave international crimes, even though the crimes were committed elsewhere and the accused and victims are not country nationals. For the most part, countries’ laws require the suspect of these international crimes be present on their territory or be a resident before national authorities can invoke jurisdiction in these cases.[15]

Germany, Sweden, and Norway are the only countries in Europe with “pure” universal jurisdiction over war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide—meaning that no link is required between the countries and the crime for national authorities to have jurisdiction, and investigations into these cases can proceed even if the suspect is not present on their territory or a resident. Nonetheless, prosecutors have broad discretion to decide whether or not to pursue investigations if the suspect is not in the country, reflecting in part the practical difficulties of securing justice in the absence of the accused.[16]

While a number of European countries have ongoing investigations related to grave abuses in Syria such as torture and other war crimes and crimes against humanity, Sweden and Germany are the first two countries in which individuals have been prosecuted and convicted for these crimes.

Syrians in Sweden and Germany

Germany and Sweden have received the highest number of Syrian asylum applications of all European countries—64 percent of 970,316 total applications between April 2011 and July 2017 (507,795 in Germany, 112,899 in Sweden), according to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees.[17]

Syrians interviewed by Human Rights Watch in Germany and Sweden consistently stressed the importance of bringing to justice those responsible for atrocities committed in Syria. Interviewees cited a range of reasons, including helping to restore dignity to victims by acknowledging their suffering. Ahmad, a journalist who explained he was detained and tortured by the Syrian government for his press work, said:

If we keep silent it’s like we are involved in the crime. For me and for others the priority is justice. I’ve been tortured, jailed for something that was legal. My rights have been violated.[18]

Samira, who lost several members of her family in the war and said she witnessed various atrocities, expressed her personal desire for justice:

My brother was killed with 14 bullets by the regime. I saw awful things, all my family died. I saw five children being executed, I saw their heads being cut off. I couldn’t sleep for a week. […] It’s very important to have justice which will let me feel that I’m human.[19]

For other interviewees, these proceedings represent not only a means of redress for victims and punishment for perpetrators, but also a way of deterring future violations. Abdullah, who said he was detained and tortured by the Syrian government while still a child and had members of his family killed by government forces told Human Rights Watch:

I became a man while I was in prison. […] I suffer a lot. My father was killed in a massacre and I don’t want to see the people who did it in Sweden. These trials are important to prevent crimes in Syria.[20]

Ayman, who told Human Rights Watch he was detained and tortured in two different government facilities and had members of his family suffer the same fate, explained:

It’s not about what happened to us, it’s for the people who die in jail. It’s a political decision as well for something to happen because up to now there have been a lot of reports, but nothing has happened.[21]

Syrians Human Rights Watch spoke to in Sweden and Germany also said that prosecuting grave crimes could build respect for, and confidence in, the rule of law, and serve as a warning to perpetrators of grave abuses that they will not escape accountability. Muhammad, an activist engaged in accountability efforts on behalf of some victims in Germany, said:

These people [members of the Syrian government] think that the political solution will come and they will be able to escape to Europe. I want them to feel haunted like they’ve haunted people all their life. We need to send a message of hope to victims and to send the message to criminals that they will not escape.[22]

Aisha, who said she was detained by the Syrian government and witnessed acts of torture by government forces against family members, said: “Don’t let them live their life: if anyone wants to run away, courts are waiting.”[23]

Some interviewees also cited reasons linked to their refugee status and believed that criminal cases in their countries of asylum may help combat xenophobic discourse in Europe by showing that refugees are in fact fleeing the crimes being prosecuted and are cooperating in bringing criminals to justice.

Othman, a student who said he was detained and tortured by the Syrian government and witnessed a massacre, told Human Rights Watch that he was worried about Swedish citizens’ perception of Syrian refugees, and thought criminal proceedings would help the population feel secure:

… in Sweden, there is a lot of generalization on refugees. I face this all the time. It’s important for Swedes to feel safe. With these trials, they will know that the bad people will be punished. […] The important thing is that Swedes know that they can feel safe.[24]

Finally, some of the Syrian refugees described trials in third countries such as Sweden or Germany as a small step towards a more comprehensive justice for Syria in the long-term. Mustafa, a former humanitarian worker in Syria said:

It’s very important that this is happening. Trials are important, no matter the affiliation. It’s important to pave the way for future justice.[25]

II.Frameworks for Justice in Sweden and Germany

Sweden and Germany are the first two countries in which individuals have been prosecuted for serious international crimes committed in Syria during the current conflict.[26] There are several reasons for this.

First, both countries have laws and specialized war crimes units within their law enforcement and prosecution services focused on addressing grave international crimes committed abroad. In addition, immigration authorities in Sweden and Germany play a key role supporting the war crimes units by sharing relevant information.

Second, authorities in both countries have previous experience in prosecuting grave international crimes cases. In 1997, Germany became the first country where a person was convicted for genocide based on universal jurisdiction.[27] After war crimes units were set up in 2009, German prosecutors also prosecuted individuals for serious international crimes committed in Rwanda, eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, and Iraq.[28] Swedish prosecutors secured their first conviction for war crimes in 2006, for atrocities committed during the conflict in the former Yugoslavia in 1993.[29] Six more cases have been pursued since the creation of the Swedish war crimes units, against individuals for serious international crimes committed during the conflicts in the former Yugoslavia, Rwanda and Iraq.[30]

Third, the presence of large numbers of Syrians means that there are victims and potential perpetrators, and perhaps a greater political impetus on the part of the authorities to hold any perpetrators in their territory to account.

Laws

Sweden

In June 2014, Sweden adopted the Act on Criminal Responsibility for Genocide, Crimes against Humanity, and War Crimes.[31] The act’s provisions in large part mirror those of the Rome Statute of the ICC. It provides the basis for prosecuting genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes, and incorporates the different modes of liability typically used in international criminal law including command responsibility. War crimes committed before the act entered into force in 2014 are currently prosecuted under the Swedish Penal Code as “crimes against international law.”[32] Torture is not yet a standalone crime under Swedish law but can be charged as a war crime or a crime against humanity.[33]

According to the Swedish Penal Code, Sweden has “pure” universal jurisdiction for war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide—meaning no specific link to Sweden is required to prosecute these crimes, even if they were committed outside of Sweden and neither the alleged perpetrator nor the victims are Swedish nationals or present on Swedish territory.[34] Prosecutors have discretion to decide whether to proceed with a case based on evidence available to them, but must prosecute when there is sufficient evidence.[35]

Germany

Germany was one of the first countries to incorporate the Rome Statute of the ICC domestically through its Code for Crimes against International Law (CCAIL) in 2002.[36] This code defines war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide in accordance with the ICC treaty and also incorporates provisions on command responsibility, among other modes of liability. Under German law, torture is not a standalone offense, but can be charged as a crime against humanity or as a war crime.[37]

Under the CCAIL, German authorities can investigate and prosecute grave international crimes committed abroad, even when these offenses have no specific link to Germany. However, this form of “pure” universal jurisdiction is tempered by certain procedural restrictions.[38] In particular, article 153(f) of the German Code of Criminal Procedure gives prosecutors discretion not to open an investigation for CCAIL crimes when:

- No German is suspected of having committed the crime;

- The offense was not committed against a German;

- No suspect is, or is expected to be, resident in Germany;

- The offense is being prosecuted by an international court of justice or by a country on whose territory the offense was committed, a citizen of which is either suspected of the offense, or suffered injury as a result of the offense.[39]

Institutions

Sweden

Swedish police have a specialized war crimes unit (War Crimes Commission) exclusively tasked with investigating serious international crimes. The unit employs 13 investigators and two analysts.[40] The analysts provide investigators with relevant contextual information and advise them on witness questioning.[41] The War Crimes Commission cooperates closely with two officers from the intelligence division of the Swedish police who focus on grave international crimes.[42]

The Swedish prosecution authority also has a specialized war crimes unit (“war crimes prosecutor team”). This unit employs eight prosecutors, four of whom work full-time on these cases. The rest divide their time between the unit’s work and regular criminal cases.[43] Prosecutors in this unit lead the investigations for serious international crimes and work closely with the War Crimes Commission.[44] They generally do not need judicial authorization to open formal investigations, as might be the case in some other countries, thereby expediting the process.[45]

Both the War Crimes Commission and war crimes prosecutor team work closely with their Swedish counterterrorism counterparts, and have systems in place to regularly exchange information.[46]

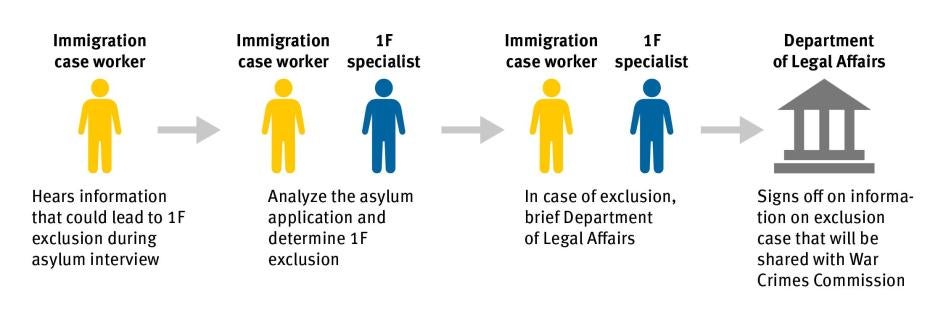

The Migration Agency processes asylum applications in Sweden. It employs over 8,000 persons and is composed of 50 units, each with 30 staff members, situated across Sweden.[47] The agency’s work is divided among six geographical regions in Sweden.[48] Specialists in each region are trained to support regular staff on cases in which article 1F, the exclusion clause of the 1951 UN Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (“Refugee Convention”), is being considered to deny refugee status, including due to the possible commission of grave crimes.[49] When such cases arise, these specialists advise case workers throughout the refugee status determination process.[50] The large number of Syrians seeking asylum in Sweden between 2014 and 2016 prompted the Migration Agency to increase the number of these experts from 20 to 35.[51]

In addition, one unit within the Migration Agency provides the organization contextual information related to specific countries and addresses country-specific questions arising from individual cases.[52]

Under Swedish law, the agency must report information on potential serious international crimes it comes across to the War Crimes Commission.[53] Human Rights Watch research showed that while the agency regularly shares information on particular asylum seekers who may be implicated in serious international crimes to the commission, it has not yet been able to do the same with respect to potential victims or witnesses of abuses.[54] When an article 1F determination case is concluded, the agency’s Department of Legal Affairs signs off on what the individual regional office can share with the War Crimes Commission.[55]

In January 2016, the Swedish law enforcement, prosecution and migration services reached an agreement to enhance their cooperation. Representatives from these three authorities now meet regularly to discuss how to improve working methods and exchange of information, including related to potential war crimes cases.[56]

Germany

The federal police have a specialized unit called the Central Unit for the Fight against War Crimes and Further Offenses pursuant to the Code of Crimes against International Law (Zentralstelle für die Bekämpfung von Kriegsverbrechen und weiteren Straftaten nach dem Völkerstrafgesetzbuch, hereinafter ZBKV).[57]

The ZBKV employs 13 police officers. While it does not employ analysts, police officers in this unit are increasingly doing more of the work traditionally done by police analysts. The unit routinely works with translators, researchers, and technical support staff provided by the federal police, as well as with external consultants. The ZBKV also has contact points at the state police in each of the 16 German states.[58]

The federal prosecution authority also has a specialized war crimes unit (“war crimes prosecution unit”) tasked with prosecuting grave international crimes under the CCAIL. The unit employs seven full-time prosecutors, including four women. The unit recently hired more female prosecutors to respond to the growing need to work with female victims of sexual violence.[59]

Similar to Sweden, the war crimes units within the law enforcement and prosecution services in Germany have counterterrorism counterparts. The war crimes and counterterrorism units often work together and have institutionalized meetings and information sharing processes in place.[60]

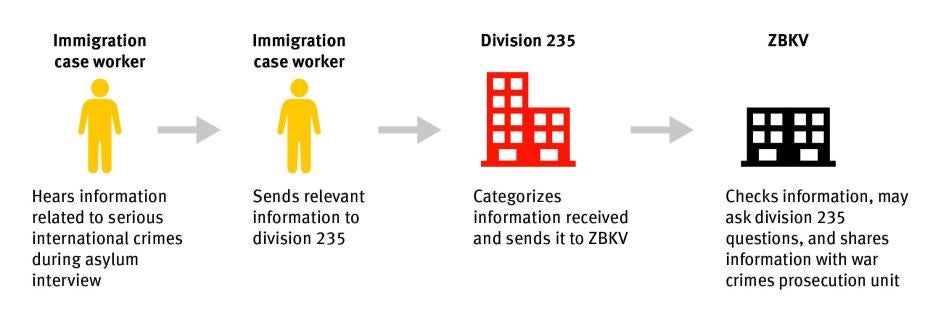

The German migration authority (Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge, hereinafter BAMF) processes asylum applications at 40 immigration centers across Germany. It has a specialized section (division 235), which acts as the focal point for collaboration with security authorities at the federal and state level, including the ZBKV and its terrorism counterpart. This collaboration includes sharing information related to potential grave international crimes. At the time of writing, division 235 employed 29 people. The BAMF also has a section tasked with deciding on article 1F exclusion cases (division 233), which can gather information relevant to determining these cases from division 235.[61]

The BAMF employs country experts who are based in the agency’s headquarters in Nuremberg, but also convenes trainings on specific country situations for immigration officials in the rest of the country. The agency also has analytical research units which draft country reports that are available to all BAMF staff.[62]

Between 2014 and 2016, the BAMF increased its overall staff from 2,000 to 9,000 to respond to the large numbers of asylum seekers in Germany. This expansion led to an overall agency restructuring, including by doubling the number of immigration centers.[63]

German criminal procedure and asylum law regulate the exchange of information between the BAMF and police.[64] Unlike its Swedish counterpart, the BAMF shares information concerning potential perpetrators as well as possible witnesses, victims and general leads. If during an asylum interview an immigration case worker comes across information relevant to crimes under the CCAIL, he or she sends it to division 235.[65] Division 235 then shares such information with the ZBKV, which analyzes it and may ask division 235 specific follow-up inquiries before sending it to the war crimes prosecution unit for further action.[66]

III.Proceedings in Sweden and Germany

At the time of writing, Swedish authorities were conducting a structural investigation into serious international crimes committed in Syria. Structural investigations are broad preliminary investigations, without specific suspects, designed to gather evidence related to potential crimes which can be used in future criminal proceedings in Sweden or elsewhere.[67] Such investigations allow authorities to collect evidence in real-time or soon after the events as opposed to years later, and have the potential to advance efforts to ensure accountability for grave international crimes in national jurisdictions. Authorities in Sweden were also conducting 13 investigations against specific individuals for crimes in Syria.[68]

German authorities were the first in Europe to open a structural investigation related to Syria, and at the time of writing were conducting two such investigations. The first, initiated in September 2011, covers crimes committed by different parties to the Syrian conflict, but includes a particular focus on the Caesar photographs. The second structural investigation, initiated in August 2014, covers crimes committed by ISIS in both Syria and Iraq, with a focus on the ISIS attack on the Yezidi minority in Sinjar, Iraq, in August 2014.[69] In addition to these structural investigations, German authorities are conducting 27 investigations against specific individuals for grave crimes committed in Syria and Iraq.[70]

To date, only seven cases related to serious international crimes committed in Syria (three in Sweden and four in Germany) have reached the trial phase. Of these, five were brought under universal jurisdiction and two under the active personality principle.[71]

ONGOING AND COMPLETED CASES FOR GRAVE CRIMES IN SYRIA [72]

| ACCUSED[73] |

BASIS OF JURISDICTION |

ALLEGED CRIMES AND CHARGES |

CASE STATUS |

|

Sweden |

|||

|

Mouhannad Droubi (Syrian non-state armed group affiliated with the Free Syrian Army) |

Universal jurisdiction |

Assaulted a member of another non-state armed group affiliated with the Free Syrian Army – War crimes and aggravated assault[74] |

Sentenced to 8 years in prison by court of appeal on August 5, 2016[75] |

|

Haisam Omar Sakhanh (Syrian non-state armed group opposed to the government) |

Universal jurisdiction |

Extrajudicially executed seven Syrian army soldiers – War crimes[76] |

Sentenced to life in prison on February 16, 2017; confirmed by court of appeal on May 31, 2017[77] |

|

Mohammad Abdullah (Syrian army) |

Universal jurisdiction |

Violated the dignity of five dead or severely injured people by posing for a photograph with his foot on one of the victims’ chest – War crimes[78] |

Sentenced to 8 months in prison on September 25, 2017[79] |

|

Germany |

|||

|

Active personality principle – Perpetrator is a German national |

Desecrated two corpses – War crimes[80] |

Sentenced to 2 years in prison on July 12, 2016[81] |

|

|

Abdelkarim El. B. (ISIS) |

Active personality principle – Perpetrator is a German national |

Desecrated a corpse – War crimes, membership in a terrorist organization, and violation of the Military Weapons Control [82] |

Sentenced to 8.5 years in prison on November 8, 2016[83] |

|

Suliman A.S. (alleged Jabhat al-Nusra)[84] |

Universal jurisdiction |

Kidnapped a UN observer – Aiding a war crime[85] |

Sentenced to 3.5 years in prison on September 20, 2017[86] |

|

Ibrahim Al F. (Free Syrian Army) |

Universal jurisdiction |

Allegedly oversaw torture, abduction, and personally tortured several people who resisted the looting of their belongings – War crimes[87] |

Trial started on May 22, 2017[88] |

To date, the cases brought to trial are not representative of the crimes in Syria. The war crimes cases that have gone to trial have nearly all been prosecutions of fighters from the Free Syrian Army and other non-state armed groups opposed to the government, ISIS and Jabhat al-Nusra, while one case was brought against a low-level member of the Syrian army. Further, most Syria-related cases in Germany involve prosecution for terrorism offenses rather than charges for war crimes or crimes against humanity.

Case Selection Concerns

As previously discussed, Swedish and German authorities are investigating potential crimes committed in Syria by different parties to the conflict, including the Syrian government.[89] However, at the time of writing, nearly all the Syria-related trials for serious international crimes in these countries had been against low-level members of ISIS, Jabhat al-Nusra, the Free Syrian Army or other non-state armed groups opposed to the Syrian government and one has been against a low-level member of the Syrian army. This case focus may also reflect the fact that curbing ISIS’s influence and deterring their own nationals from joining it are national security priorities for Germany and Sweden.

Syrians expressed frustration about the lack of cases brought against individuals affiliated with the Syrian government. “Europe is concentrating on ISIS and forgetting Assad; ISIS is a spot in the sea of Assad’s crimes,” one Syrian in Germany said.[90]

For some refugees, the frustration is personal: 22 of the Syrians Human Rights Watch interviewed in Sweden and Germany said they were direct victims of crimes committed by the Syrian government. Some said they believed some of the perpetrators were living in Sweden and Germany.[91] Abdou, who said he was among those directly victimized by the Syrian government, explained:

Germans are treating Syrians the wrong way. They see us as a mass without distinction, they’re not paying attention as to what they [Syrian government forces] have done. Germans should understand who is who.[92]

Although Swedish and German authorities are investigating crimes committed by government forces, the publicly available information about these efforts is limited and does not necessarily reflect the breadth of the ongoing probes.

According to practitioners and academics, cases against mid and high-level government officials or military commanders are more difficult to build from an evidentiary perspective than those brought to trial so far. Prosecutions against these individuals require strong evidence to connect the crimes committed to the alleged perpetrators, and evidence to place them within the chain of command.[93]

While all the accused in the cases brought to trial to date were arrested in Sweden and Germany, high-level officials or senior military commanders affiliated with the Syrian government have not yet travelled to these countries and are unlikely to travel to Europe in the near future. In addition, some could be temporarily protected from timely prosecution as a result of the official positions they hold.[94]

Human Rights Watch found that the fact that these cases are not representative of the breadth of the atrocities committed in Syria has the potential to undercut Syrian refugees’ perspectives about the proceedings and their confidence in these efforts to deliver some form of justice.

Reliance on Terrorism Charges

The type of charges upon which cases are brought further impact how representative these proceedings are overall. While this does not seem to be an issue in Sweden yet,[95] Germany has experienced a problematic proliferation of cases where the offenses charged are those available under terrorism laws, even when it is likely the suspect committed a war crime or crime against humanity.[96]

The legal framework for terrorism in Germany is broad. The German Criminal Code penalizes the acts of membership in, support of, and recruitment for a terrorist organization and judges can in each case determine whether an organization qualifies as terrorist or not.[97] Recent provisions have also been added to penalize the act of financing a terrorist organization and traveling outside Germany with the intent to receive terrorist training.[98]

According to practitioners interviewed in Germany, it is often easier to find evidence to prove that an individual is a member of a terrorist organization than to link such individual to any underlying serious criminal act.[99]

When it is possible to bring someone to trial for both serious international crimes and terrorism, and there is insufficient evidence for a serious international crime prosecution, authorities will charge the suspect with terrorism-related offenses rather than release them from custody.[100]

There are costs, however, to prosecuting individuals solely on terrorism charges, when they may also be responsible for war crimes or crimes against humanity. In Germany, serious international crimes are punished with longer prison sentences than those usually prescribed for terrorism offenses.[101] In addition, terrorism charges often do not reflect the scope and nature of abuses committed, and risk undermining efforts to promote compliance with international humanitarian law. The use of terrorism charges as means of investigating and prosecuting individuals believed to be responsible for war crimes could send a signal that the authorities’ rightful determination to tackle domestic threats eclipses their responsibility to deliver accountability for other serious international crimes. The use of terrorism charges also risks diverting police and prosecutorial resources earmarked for international justice to already well-resourced domestic national security efforts.

The German public prosecutor general stated that situations like those in Syria and Iraq show that terrorism and other serious international crimes are increasingly intertwined as terrorist organizations are new actors in these conflicts. He explained that to fully register the unlawfulness of these acts and provide appropriate retribution, international criminal law must not be neglected.[102] Referring to Syria he noted:

[T]he character of the terrorist organizations involved in the conflict, as well as the nature of the specific single acts, can only be fully grasped if they are viewed not only through the lens of counterterrorism, but also viewed in the context of international criminal law.[103]

IV.Challenges

Swedish and German authorities have encountered several challenges in their efforts to investigate and prosecute grave abuses committed in Syria. Their experiences provide valuable lessons domestically, and for other countries in Europe and elsewhere set to take up cases involving serious international crimes in Syria.

Some of these challenges are inherent to accountability efforts for international crimes at the domestic level. Others are specific to Syria-related cases and are tied to information gathering efforts both within and outside Sweden and Germany. While some of these obstacles are difficult to overcome, authorities are already taking steps to address others.

The combination of these inherent and situation-specific challenges likely impacts both the number and the type of cases brought to trial to date in each of these countries, as well as the way Syrian refugees perceive these justice efforts and contribute to them.

Standard Challenges

Authorities pursuing cases on the basis of universal jurisdiction encounter challenges that are inherent to these types of cases. Solutions to some of these challenges are beyond the reach of authorities.

Domestic prosecutions for serious international crimes are opportunistic efforts, usually brought against people present in the territory of the prosecuting country—as is the case with the cases brought to trial to date in Germany and Sweden.

|

Case Profile: Haisam Omar Sakhanh In September 2013, the New York Times released a video showing members of a Syrian non-state armed group opposed to the government extrajudicially executing seven captured Syrian government soldiers in Idlib governorate on May 6, 2012. The video was smuggled out of Syria a few days earlier by a former fighter who sent it to the New York Times. One of the fighters in the video was Haisam Omar Sakhanh. In February 2012, Sakhanh was arrested in Italy, where he had been a permanent resident since 1999, in relation to a demonstration at the Syrian embassy in Rome. He was later released and decided to return to Syria. In 2013, Sakhanh travelled to Sweden where he applied for asylum. During his asylum interview, he failed to disclose information about his arrest in Italy. This omission triggered an investigation that eventually linked him to the New York Times video. Sakhanh was arrested in Sweden in 2016 and charged for his part in the killing of the seven government soldiers as a “crime against international law.” His trial took place in the Stockholm District Court between January 11- 23, 2017. While Sakhanh admitted to the shooting, he said he was merely carrying out the decision of an opposition court, which ordered the execution of the soldiers. He failed to produce any evidence to substantiate that claim. On February 16, 2017, the Stockholm District Court convicted Sakhanh and sentenced him to life in prison. While the Swedish judges found that non-state actors can establish courts, in this case they held that such a court was neither independent nor impartial and did not offer the legal guarantees of a fair trial. The judgment and sentence were confirmed by the Svea Appeal Court on May 31, 2017. |

Immunity for sitting government officials can represent an additional obstacle to prosecuting certain individuals implicated in serious international crimes. According to this principle, certain foreign government officials, such as accredited diplomats, heads of state and government, and foreign ministers are entitled to temporary immunity from prosecution by foreign states while they hold their positions, even for serious international crimes. The immunity ceases once the person leaves office and should not bar later prosecutions.[104] Both Sweden and Germany recognize this principle and have incorporated it in their domestic laws.[105]

Other typical challenges can be tackled by domestic authorities, who, if provided with adequate resources, would be in a better position to take steps to try to overcome them.

For example, criminal cases for serious international crimes are complex and require more time and resources than regular criminal cases, placing special demands on and requiring special expertise from police, prosecutors, defense and victims’ counsel and courts. Gathering evidence—most often from victims and witnesses to the actual crimes—usually requires traveling to the country where the violations occurred. This presents a range of challenges, including linguistic and cultural barriers and possible resistance from national authorities. These cases also usually touch on offenses and modes of liability that are unfamiliar to domestic investigators and prosecutors.

The experience of a number of European countries indicates that specialized war crimes units, trainings for practitioners involved in these types of cases, and adequate resources for investigative and prosecutorial efforts have proven effective in overcoming these challenges.[106]

Syria-Specific Challenges

In addition to these standard challenges, the overarching difficulty for authorities working on cases related to Syria is operating amid an ongoing conflict, with no access to locations where crimes were committed. This obliges authorities to look elsewhere for relevant information to build cases.

In addition to publicly available platforms, such as social media, there are three main sources of such information: Syrian refugees and asylum seekers present on the territories of countries engaged in these investigations; other governments and intergovernmental entities; and various nongovernmental documentation groups working beyond their borders.

Domestic Information Gathering

Sweden and Germany are in different phases of information gathering at the domestic level. While Swedish investigators are encountering difficulties collecting information from Syrian refugees and asylum seekers, their German counterparts are struggling to filter the large amount of information they are receiving from various sources.

The first three Syria-related trials for grave international crimes completed in Sweden were not part of a strategic investigative effort, but rather based on incriminating photographs and videos which were used by the war crimes prosecutor team to build these cases.[107] In addition to this photographic and video evidence, Swedish prosecutors relied mainly on expert witnesses to clarify controversial legal issues or to provide contextual information on the situation in Syria at the time of the crimes.[108]

Swedish authorities are now trying to develop a more defined prosecutorial strategy building on information collected as part of their structural investigation. In this context, investigators have started to reach out to Syrian refugees living in Sweden but told Human Rights Watch that they face difficulties finding individuals willing to testify in court.[109]

One practitioner explained that, to achieve a more strategic approach, Swedish investigators and prosecutors need “hard facts and people willing to come forward” to build cases for serious crimes committed in Syria.[110] Two other practitioners recognized the importance of leads for these investigations, but told Human Rights Watch that authorities still need eye witnesses, regardless of other information that may be brought to their attention.[111]

German authorities are facing a different challenge: a large amount of general, unfiltered, and often unsolicited information from different sources. This means that investigators must filter this information first, before turning their attention to more strategic outreach efforts.

As of June 2017, the ZBKV had received about 4,100 tips (2,760 related to Syria), some of which eventually led to 27 targeted investigations against individuals for crimes committed in Syria and Iraq.[112] Interlocutors explained that the ZBKV has been flooded with information from different sources, including the BAMF and the general public. The latter often directs investigators to potential leads on social media.[113] All this information needs to be checked and, according to one practitioner, the large number of tips makes discerning the veracity of information difficult, in part because much time and resources are needed to sift through the information for lines of inquiry relevant to their ongoing investigative efforts, as well as to identify witnesses with first-hand knowledge of the crimes.[114] One practitioner described this process as akin to a mini preliminary investigation.[115]

Against this background, Syrian refugees in Sweden and Germany can play an important role in supporting the authorities in their efforts. However, investigators and prosecutors in both countries are encountering difficulties in their engagement with refugees, mainly due to mistrust on the part of asylum seekers and refugees towards authorities, fear, and a general lack of awareness.

Mistrust

Syrian refugees told Human Rights Watch they often do not trust the police and other officials due to negative experiences with authorities in their home country.[116] Ahmad, who lives in Sweden, said:

We are used to looking at the police or the government as a threat. If you have a right you want to follow in Syria you prefer not to, because the police will try to take money from you. No trust. Even in Sweden, if I see a policeman I don’t feel normal. We don’t look at the police and the government as someone we can trust.[117]

Other refugees said this mistrust also stems from their perception that the Swedish and German governments support the Syrian government and are indifferent toward ordinary Syrians’ suffering, despite the fact that the two countries host far larger numbers of Syrians than most other EU countries.[118] Ibrahim, who lives in Germany, said:

The general atmosphere here is against you. You don’t feel like someone would really care about you.[119]

As such, some interlocutors said authorities in both countries needed to be particularly sensitive in their engagement with refugees given their experiences, including crimes they might have suffered firsthand or witnessed. Refugees Human Rights Watch spoke to described a depersonalized asylum process and reported negative experiences interacting with immigration officials in particular. One refugee said:

When you’re treated like a number and no one is listening, it makes you uncomfortable to share sensitive, personal information […] I’m not just a victim or only a refugee […] You feel violated from the first second you are here.[120]

Fear of Reprisals

Many refugees Human Rights Watch spoke to in Sweden and Germany still had family and friends in Syria, making it difficult for authorities to find individuals willing to publicly testify about any crimes they might have suffered or witnessed.

Several refugees interviewed in Sweden told Human Rights Watch that they would be willing to cooperate generally with authorities, but are reluctant to appear in open court or provide named testimony because they are afraid for the safety of their families back in Syria.[121] One refugee explained he would not testify publicly because he believed ISIS and the Syrian government were active in Sweden.[122] Swedish law does not allow the use of anonymous witnesses in criminal trials, although there is scope for more limited witness protection measures.[123]

Similar concerns were raised in interviews conducted in Germany. In addition to concerns over the safety of families in Syria, some refugees said that they were also personally afraid because they believed Syrians affiliated with the government and now living in Europe could harm them.[124] German law allows for the identity of witnesses to be concealed in limited circumstances (for example, victims of sexual violence).[125] However, anonymity is rarely used because such testimony can only be given limited weight, and prosecutors therefore see it as a last resort.[126]

Lack of Awareness

Human Rights Watch research also revealed a general lack of awareness among Syrian refugees about serious international crimes proceedings. This included:

- Lack of knowledge of the legal systems in place and the possibility for Syrian refugees to contribute to justice efforts;

- Lack of knowledge of victims’ right to participate in criminal proceedings; and

- Lack of knowledge about the ongoing cases.

Legal System

Syrian refugees’ willingness (and ability) to share information with authorities may be impacted by their lack of knowledge of the mandates and work of immigration authorities, law enforcement, prosecutorial services and how they interact with each other.

This is particularly true in relation to the delicate issue of immigration status. If immigration authorities do not make clear to asylum applicants their mandate and the distinction between the asylum process and criminal investigations, Syrian asylum seekers may be reluctant to share information for fear it may impact their claims for protection.

According to several Syrian refugees in both countries, asylum seekers often deny having witnessed or being victims of crimes during their asylum interview because they believe such disclosure will negatively affect the ultimate decision on their status.[127] Raslan said he was reluctant to share information during his asylum interview:

I didn’t ask too much and didn’t say too much. I was afraid for my papers, for myself and for my family back in Syria. […] I didn’t say I saw something in Syria, even if I did.[128]

Two interviewees in Sweden said that many asylum seekers in the country appeared to believe they would be better placed to attribute their flight from Syria to ISIS during asylum interviews even if they fled from government forces or from other armed groups. This belief appeared to be based on the assumption that citing ISIS would more likely result in a positive status determination because of the group’s bad international reputation.[129]

Similar stories also circulated among asylum seekers in Germany. Some interviewees were told by other refugees not to mention any crimes they might have suffered at the hands of Syrian government forces because it would “complicate” their asylum process.[130]

None of the Syrian refugees Human Rights Watch interviewed in Sweden and Germany said they were told they had a right to report to the police when they disclosed to the immigration officials information about crimes they were victims of or witnessed. Fifteen interviewees who shared this information with the immigration authorities told Human Rights Watch that they did not know that they could also share it with the police and how to go about doing that.[131]

Ibrahim complained about the lack of information available on how to contact the competent authorities: “Why don’t they tell us? I don’t know where to go if I want to say something.”[132]

Victims’ Right to Participate in Proceedings

Under Swedish law, victims have the right to initiate criminal proceedings or participate as civil parties in cases initiated by prosecutors. They are entitled to free legal representation.[133] Under German law, victims of specific crimes can join proceedings as “private accessory prosecutors” and have a right to free legal counsel, which is automatically appointed.[134]

None of the refugees interviewed were informed of their right to participate in legal proceedings during or after the asylum process.[135] Ayman filed a criminal complaint as part of a group of victims with the German prosecutors against some senior Syrian officials.[136] He told Human Rights Watch that he only learned about the possibility of such action after speaking with one of his Syrian friends who is a lawyer.[137]

Ongoing Cases

The majority of the Syrian refugees Human Rights Watch interviewed in Sweden and Germany either had no knowledge about the criminal proceedings taking place in their host country, or limited (and often incorrect) information.[138] Those who had some accurate information about these proceedings reported learning it from the Facebook pages of Syrian activists.[139] Some said they wanted to receive more information about these and potential future cases from official sources, preferably in Arabic.[140] They cited social media, and Facebook in particular, as effective platforms to publicize any updates about the cases.

The Syrian crisis is distinct from other situations Swedish and German investigators and prosecutors have worked on in the past. The large presence of Syrian refugees and asylum seekers on their territories and the important role they can play gives rise to new demands on the authorities to effectively engage with these affected communities.

Trials in Sweden and Germany are not videotaped or televised, but they are usually open to the general public and media.[141] The proceedings are conducted in Swedish and German, and in the Syria prosecutions that have gone forward Arabic translation is provided to the defendant. Information on the proceedings (usually in relation to an arrest, the beginning of a trial or a judgment) is sometimes published on the websites of the prosecutors and the police, but is only available in Swedish or German.[142] Judgments and other relevant court documents are also only available in Swedish and German. German prosecutors are also seeking the translation of interlocutory—that is provisional—decisions as well as judgments into the languages relevant to particular cases.[143]

In February 2017, Swedish prosecutors organized a press conference to discuss two recent judgments (one related to Syria) and to explain the work of the war crimes prosecutor team.[144] Prosecutors in Germany usually hold a press conference once a trial is over and convene a press conference once a year to discuss their work overall.[145] While these initiatives are valuable and show openness on the part of authorities, they are only held in Swedish and German and do not involve proactive engagement with affected communities.

Swedish and German media have not systematically covered the most recent Syria-related cases.[146] Practitioners in Sweden noted that journalists usually reach out to investigators and prosecutors when there is a new case but there is generally no interest in covering the proceedings afterwards.[147] What coverage exists is also only available in Swedish and German. Syrian refugees in Sweden told Human Rights Watch that there is no Arabic-speaking media outlet that they trust to deliver this kind of information.[148]

Interviewees in both countries said the press does not seem interested in these cases and some attributed this to the public’s fatigue about Syria-related news, strong interest in national security issues and ISIS, as well as a lack of understanding about legal concepts such as war crimes.[149]

Impact of Limited Outreach on Syrian Refugees

Inadequate outreach to affected communities in Sweden and Germany can have direct impact on the success of accountability efforts in relation to serious international crimes committed in Syria. Fear and mistrust on the part of Syrians in Sweden and Germany inhibits their willingness to share potentially probative information with the authorities. Lack of awareness and understanding of the proceedings and systems in place further fuels these attitudes and likely prevents Syrians from fully understanding these justice efforts and being able to contribute to them.

Abdou, who said he was a victim of crimes perpetrated by the Syrian government and now lives in Germany, said that “Germans didn’t open doors for this community to be involved in these procedures in general.”[150]

On the other hand, knowledge of these proceedings and how to contribute to them might provide Syrians in Sweden and Germany with a sense of justice and allow them to feel like stakeholders in these efforts and could potentially also help integrate them into society. Samira, who lives in Sweden, explained that she has information she wants to share about crimes she witnessed in Syria, but did not know she could:

No one hears my voice, no one told me I could talk. I would love to share information, to see the truth and show how much we have suffered.[151]

At the same time, Syrian refugees sometimes expressed to Human Rights Watch unrealistic expectations about how they might contribute to the prosecution of serious international crimes and the outcome of these cases. Their skewed expectations at times stemmed from a lack of familiarity about the legal systems in place and the limitations of these proceedings.

Because of the constraints of their mandates and resources, domestic authorities often cannot utilize the information Syrian refugees provide to build cases. Despite a willingness of some Syrians who have witnessed and/or documented serious crimes to share information with authorities,[152] the information often does not relate to events within their jurisdiction or meet the evidentiary threshold required for criminal prosecutions in Sweden and Germany.

In addition and as outlined above, cases brought before domestic courts for crimes committed abroad often depend on the physical presence of suspects and the availability of evidence. In the context of the ongoing conflict in Syria, it is unlikely that senior government officials or military commanders will travel to Europe in the near future, reducing the likelihood of cases being brought against mid to high-level individuals affiliated with the government.

But these constraints are not necessarily apparent or communicated to Syrian communities in Sweden and Germany, causing frustration and a loss of faith in the authorities. Hakim, a journalist detained by the Syrian government, said: “Most people who want the regime on trial lost hope.”[153]

Regional and International Information Gathering

Swedish and German authorities are also looking outside of their borders to gather information relevant to their efforts to bring justice for grave crimes committed in Syria. While the European Union offers platforms to facilitate the exchange of information between its member states, cooperation with countries outside the EU is more difficult. Nongovernmental organizations, as well as UN bodies, are also playing an increasingly important role in documenting abuses committed in Syria. Investigators and prosecutors are looking for better ways to interact and cooperate with these entities.

Countries in Europe

Swedish and German authorities reported effective cooperation at the European level due to protocols that allow for the swift exchange of information.[154]