- What is the background in the Central African Republic to these cases?

- How did the ICC become involved in the Central African Republic?

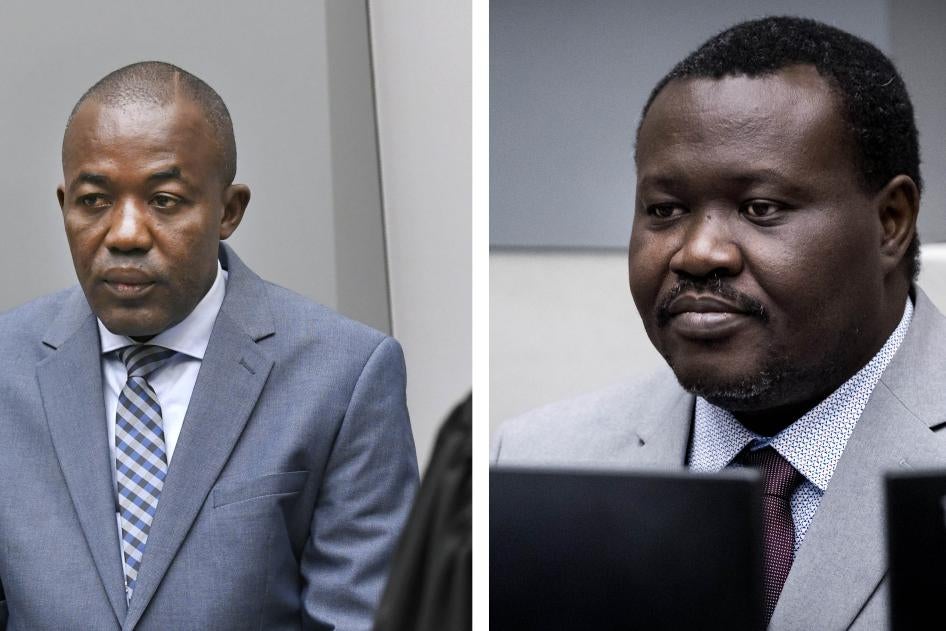

- Who are Alfred Yékatom and Patrice-Edouard Ngaïssona?

- When did Yékatom and Ngaïssona first face ICC charges and appear at the ICC?

- What are the charges against Yékatom and Ngaïssona?

- Why is the ICC trying Yékatom and Ngaïssona together?

- How does this trial relate to the previous trial of Jean-Pierre Bemba?

- What does recent unrest in the Central African Republic mean for the trial?

- What are Yékatom’s and Ngaïssona’s rights as defendants?

- What is the role of victims in Yékatom’s and Ngaïssona’s case? Can they participate in the trial?

- How will local communities affected by the crimes in the Central African Republic receive information about the trial? Will they be able to follow the trial in The Hague?

- What will happen at the trial hearing? How long will the trial last? What will be the punishment in the event of conviction?

- How does this trial relate to the Special Criminal Court that has been established in the Central African Republic? Could Yékatom and Ngaïssona be tried by this court or by domestic courts in the country?

- What else is the ICC doing in the Central African Republic? What more should it do?

Correction: This Q&A has been corrected to reflect the correct number of victims that have so far been allowed to participate in the trial phase, as opposed to during pre-trial proceedings.

The opening of the trial of Alfred Yékatom and Patrice-Edouard Ngaïssona will take place on February 16, 2021 at the International Criminal Court after being postponed from February 9 due to unexpected Covid-related circumstances. Ngaïssona and Yékatom are the highest ranking anti-balaka leaders to face trial, and the first at the ICC. The anti-balaka are Christian militias who engaged in brutal tit-for-tat attacks with the Muslim Seleka following a coup in 2012, leaving civilians caught in the middle. Although the International Criminal Court is conducting two investigations concerning crimes committed in the Central African Republic in the last two decades, this is the first trial of anti-balaka leaders and involving crimes in the country’s conflict since 2012.

In late 2012, mainly Muslim Seleka rebels began a rebellion that ousted the Central African Republic president, François Bozizé, and seized power through a campaign of violence and terror. In late 2013, Christian and animist militias known as anti-balaka began to organize counterattacks against the Seleka. The anti-balaka had its roots as local self-defense groups that existed under Bozizé and frequently targeted Muslim civilians, associating all Muslims with the Seleka.

As the Seleka and anti-balaka fought each other and carried out increasingly brutal tit-for-tat attacks on those they perceived as supporting their enemies, civilians were caught in the middle. Many Muslims fled, and with the mass departure of the country’s minority Muslim population, the anti-balaka turned on Christians and others who they believed had opposed them or had sided with their Muslim neighbors. Over time, the anti-balaka turned on anyone they came across, stealing and looting. There was widespread internal displacement across the country, which continues.

Human Rights Watch has documented war crimes and crimes against humanity committed by Seleka and anti-balaka forces since 2013. Some of the most egregious abuses occurred in the central regions of the Central African Republic between late 2014 and April 2017. Human Rights Watch has also documented hundreds of cases of rape and sexual slavery by anti-balaka groups and fighters from Seleka factions.

On May 30, 2014, then-interim president Catherine Samba-Panza referred the situation in the Central African Republic since August 2012 to the International Criminal Court in The Hague. On September 24, 2014, the prosecutor announced the opening of an investigation into crimes allegedly committed in the Central African Republic since 2012.

This was the second ICC investigation into alleged crimes in the Central African Republic. The ICC’s first investigation related to grave crimes committed in 2002 and 2003 during a coup led by Bozizé. In December 2004, the Central African Republic referred that situation to the ICC, and the ICC prosecutor announced the opening of a formal investigation into the situation in 2007.

Alfred Yékatom, known as “Rombhot,” was born on January 23, 1975. He was a master corporal in the national army before the conflict and then promoted himself to “colonel” when he became a key anti-balaka leader in 2013. He allegedly commanded a group of about 3,000 members operating within the anti-balaka movement, according to the ICC. On August 20, 2015, Yékatom was added to the United Nations Security Council sanctions list for taking action that was deemed to threaten or impede the political transition process or fuel violence. In 2016, Yékatom was elected to parliament.

Patrice-Edouard Ngaïssona is a one-time self-declared political coordinator of the anti-balaka militias and, according to the ICC, an “alleged most senior leader” of the anti-balaka. On February 2, 2018, he was elected to a senior post at the Confederation of African Football. Human Rights Watch interviewed Ngaïssona on September 3, 2014, during which he did not contest that the anti-balaka were responsible for some abuses or that he was a leader of the anti-balaka.

The ICC issued an arrest warrant for Yékatom on November 11, 2018, which it unsealed on November 17, 2018. Yékatom was transferred to the ICC by Central African Republic authorities on November 17, 2018. The authorities in the Central African Republic took Yékatom, who was then a member of parliament, into custody after he took out a gun and fired shots in the parliament building. He made his first appearance before the ICC a few days later.

Less than a month later, on December 7, 2018, the ICC issued an arrest warrant for Ngaïssona. Ngaïssona was arrested in France on December 12, 2018 and transferred to the ICC on January 23, 2019. His initial appearance took place two days later.

Yékatom faces 10 counts of war crimes and 11 counts of crimes against humanity and Ngaïssona faces 16 counts of war crimes and 16 counts of crimes against humanity. The charges include intentionally directing an attack against the civilian population, murder, intentionally directing attacks on religious sites, deportation or forcible transfer of population and displacement of the civilian population, and persecution. Both were also charged with the war crime of enlisting children under age 15 and using them in hostilities.

When confirming these charges to go ahead to trial, the ICC judges denied certain charges that the prosecutor had sought relating to events in certain locations outside Bangui, the Central African Republic’s capital. The judges said that the evidence did not establish that Ngaïssona had effective control of certain anti-balaka groups operating outside Bangui.

Victims initially raised a concern that the prosecutor might not include rape and sexual violence charges as distinct offenses. The charges ultimately did include rape, both as a war crime and a crime against humanity, although only against Ngaïssona. The prosecutor later sought to add a second instance of rape to Ngaïssona’s charges and to add charges of rape and sexual slavery against Yékatom. The court denied the requests, however, citing among other reasons the need to balance the effectiveness of the prosecution with potential prejudice to the defendants given the late timing.

Human Rights Watch has previously documented rape and sexual slavery by anti-balaka forces, including by forces allegedly under Yékatom’s command.

In February 2019, the ICC judges joined the Yékatom and Ngaïssona cases. They noted that the crimes were part of the same overall attack and the same conflict. As a result, the judges said, they expected that the evidence against both suspects would be substantially the same. The judges also found that joining the cases would not prejudice the defendants, and would rather enhance the fairness and expeditiousness of the proceedings. In joint proceedings, each suspect is accorded the same rights as if they were being tried separately.

The ICC’s first investigation into grave crimes committed in 2002 and 2003 has produced only one case, against Jean-Pierre Bemba, a former vice president from Congo. Forces from Bemba’s Movement for the Liberation of the Congo (Mouvement pour la Liberation du Congo, MLC) were active in the Central African Republic in 2002 and 2003, acting at the behest of then-president Ange-Félix Patassé in repressing a coup attempt by Bozizé.

Bemba was arrested in Belgium in 2008 and his trial began in 2010. On March 21, 2016, ICC judges found him guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity and sentenced him to 18 years in prison. An ICC appeals chamber overturned the conviction. He was released three days later and went to Belgium. The ICC denied a claim Bemba filed against the ICC for compensation and damages.

The ICC has since closed the Bemba case, although the ICC’s Trust Fund for Victims is undertaking certain activities through a pilot project begun in September 2020 to provide assistance to victims of crimes involved in this situation. This includes physical and mental health, rehabilitation, and material support to victims and their families.

The ICC has not issued any other arrest warrants in connection with its first investigation. The court has yet to hold anyone to account for the crimes in 2002 and 2003, leaving victims without redress.

The Central African Republic held presidential elections on December 27, 2020. On January 4, 2021, the electoral commission declared Faustin-Archange Touadéra the winner of the presidential election with 53.9 percent of the vote. On January 19, the Constitutional Court affirmed the election results.

In the run-up to and following the elections, a new rebel coalition has carried out multiple attacks. The Coalition of Patriots for Change (Coalition des patriotes pour le changement, CPC) includes the same groups that have committed war crimes in the last five years, on both sides of the conflict.

In the recent unrest, scores of civilians, several peacekeepers, and a Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) aid worker have been killed. Between December 22 and 29, the UN peacekeeping mission in the Central African Republic, known by the French acronym MINUSCA, noted at least 57 incidents of human rights abuses and 96 victims surrounding election violence, primarily by armed groups, but there have been several additional attacks since. The violence has led to mass displacement, with over 100,000 civilians fleeing to neighboring Chad, Cameroon, and the Democratic Republic of Congo, and another 100,000 civilians fleeing into the bush.

On December 19, a government spokesman said that former president Bozizé was behind the new coalition. Bozizé, president from 2003 until he was ousted in a 2013 coup, returned to the country a year ago. In early December, the country’s constitutional court ruled him ineligible to run in the December 27 presidential election on “moral grounds” as he is under UN sanctions and the subject of an international arrest warrant issued by the Central African interim government in 2014.

On December 31, President Touadéra dismissed three rebel chiefs from the government as a result of the attacks, which could end a peace deal that 14 rebel groups had signed in February 2019.

The UN Security Council has condemned the attacks and called for accountability for the crimes. High-level officials from the African Union, Economic Community of Central African States, European Union, and United Nations have also issued a joint statement in which they invited the government to open an investigation to bring to justice those responsible for the violence.

The UN special advisers on the prevention of genocide and responsibility to protect have noted that the current climate of impunity is a major factor fueling the violence and insecurity in the country.

The ICC prosecutor issued a statement prior to the election calling for “calm and restraint” and reminding that anyone who participated in crimes would be “liable to prosecution.” Prosecutors in the Central African Republic have stated that an investigation has been opened into Bozizé’s role in the rebellion.

Yékatom and Ngaïssona are presumed innocent until proven guilty and are entitled to a fair and expeditious trial, conducted impartially. Additionally, under international fair trial standards such as those found in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the ICC’s founding Rome Statute, they are entitled to:

- Get information about the charges against them in a language they understand;

- Have adequate time and facilities to prepare a defense;

- Not be compelled to testify against themselves or to confess guilt;

- Each have a lawyer of their own choosing; and

- Be protected from torture and cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment.

Yékatom and Ngaïssona have both raised concerns regarding respect for their fair trial rights. They asserted that the prosecutor violated obligations on how to disclose material to the defense on several occasions. While the ICC judges agreed, they also found that the prosecutor had either remedied the problems or that there had been no prejudice to the defense.

Ngaïssona also has complained about his detention conditions, and requested in-person visits by his defense team, which have been prohibited due to the Covid-19 pandemic. The ICC judges denied the request. Most recently, Ngaïssona’s Defense counsel requested an evaluation by a medical expert in light of the purported deterioration of his mental well-being, but the ICC judges noted that this issue should be handled by the court’s registry.

The ICC has an innovative system of victim participation for an international criminal tribunal. Victims of the alleged crimes can make their views and concerns known to the judges in the trial, separate from any role as witnesses, through their legal representatives. Victim participation is one way to enhance the ICC’s resonance in affected communities.

The ICC judges allowed 1,085 victims to participate in the pre-trial phase. The ICC judges have so far recognized 325 victims as participants in the trial phase. The in-person registration of new victim participants has been complicated by the pandemic, but the ICC is continuing its efforts to register victims. In light of the pandemic, victims may continue to register until the close of the prosecution’s presentation of evidence. The ICC judges will also decide whether victims authorized to participate in the pre-trial phase may also participate in the trial phase.

The victims are divided into two distinct groups: one consists of former child soldiers and the other of victims of other crimes. The creation of two distinct groups takes into account that their interests might diverge as former child soldiers could have been implicated in crimes against victims of other crimes.

Two teams of lawyers represent the victim participants. The legal representatives for victims will be allowed to make opening statements and to participate in all hearings. They may also ask questions to witnesses and present evidence, after obtaining permission from the chamber.

- How will local communities affected by the crimes in the Central African Republic receive information about the trial? Will they be able to follow the trial in The Hague?

Outreach in the affected communities is important to maximize the court’s impact locally. As part of this effort, the ICC produces audio, video, and written summaries of court proceedings, and conducts field missions to discuss developments with affected communities. The pandemic has constrained outreach activities, but the ICC has continued its efforts, with a greater reliance on radio partners, including 20 community radio stations, as a method of mass dissemination of information. It has also displayed billboards in Bangui and the country’s provinces with messages promoting justice and accountability.

Ahead of the trial, the ICC will broadcast a question-and-answer dialogue on local radio, and already has been working to answer key questions on people’s minds in local print media. The ICC has planned to stream the opening of the trial in a courtroom in Bangui, with members of the affected communities, journalists, civil society members, and international and national authorities invited to attend. The opening will also be broadcast live on television. As the trial gets under way, the ICC will broadcast summaries of trial developments every month on both television and radio.

- What will happen at the trial hearing? How long will the trial last? What will be the punishment in the event of conviction?

The opening of the trial is scheduled for February 16, 2021 (after being postponed) and is scheduled to last three days. After some procedural issues are addressed, the prosecution will have six hours to present its opening statements. The victim participants and the Ngaïssona defense will then have three hours each for their opening statements. The Yekatom defense will make its opening statement at the beginning of the presentation of its evidence.

The prosecution’s presentation of evidence is expected to run from March 15 to 31, but then to be continued at a later time. The Office of the Prosecutor has indicated it will call 147 fact witnesses and four expert witnesses. The prosecution has estimated that it needs approximately 400 hours to examine its witnesses. The ICC judges have allocated a maximum of 200 hours to each defense team for questioning. The ICC has indicated the trial may last approximately two years.

Following the presentation of the evidence, the judges will determine a verdict. In the event of conviction, imprisonment for up to 30 years, or life in prison may be imposed. The death penalty is not an available punishment before the ICC.

- How does this trial relate to the Special Criminal Court that has been established in the Central African Republic? Could Yékatom and Ngaïssona be tried by this court or by domestic courts in the country?

The ICC is a court of last resort. Under the Rome Statute, the ICC only prosecutes cases when national courts are unable or unwilling to prosecute.

In 2015, the Central African Republic established a Special Criminal Court in Bangui to try serious international crimes committed in the conflict, alongside the ICC. The court operates in partnership with the UN and includes international judges and prosecutors working with Central African Republic justice practitioners.

The Special Criminal Court is given primacy over the country’s ordinary national courts. The law establishing the court foresees that if the both courts work on the same case, priority will go to the ICC, which is a bit different from the usual practice between the ICC and national courts.

The court became operational in 2018 and investigations are underway, although it has not yet held its first trial. It has a mandate of five years, which can be renewed. The court needs increased international support to continue its work.

Yékatom has argued that the ICC should find his case to be inadmissible on the grounds that the Central African Republic is now capable of prosecuting him in the Special Criminal Court. The ICC has denied the request because no investigations or prosecutions against Yékatom are underway at the Special Criminal Court and the Central African Republic authorities have not given any indication that they intend to investigate or prosecute him. An appeal to this decision by the defense is pending.

There have also been criminal trials before ordinary courts of the Central African Republic since 2015, including at least two proceedings against former anti-balaka commanders. In February 2020, the Bangui Court of Appeal sentenced 28 anti-balaka fighters for the killing of 75 civilians and 10 UN peacekeepers around Bangassou, in Mbomou province, in 2017. The sentences ranged from 10 years to life. However, most other proceedings have been against low-ranking individuals or have concerned minor crimes.

Since the Bemba acquittal, the ICC has brought no further cases as part of its first investigation. Human Rights Watch has criticized the lack of additional cases and has urged the Office of the Prosecutor to pursue charges that are representative of the crimes committed to ensure meaningful delivery of justice.

With respect to the ICC’s second investigation, until recently, the prosecution of two anti-balaka leaders was in stark contrast to the lack of proceedings against Seleka leaders and their allies, who continue to control vast territory in the country. However, on January 24, 2021, the Central African Republic surrendered the first Seleka-affiliated suspect to the ICC. Mahamat Said Abdel Kani is accused of war crimes and crimes against humanity committed as a Seleka commander in Bangui in 2013. The ICC issued the arrest warrant under seal on January 7, 2019. His initial appearance was held on January 28, 2021. Human Rights Watch has urged the court to bring charges against more Seleka suspects, particularly higher-level Seleka suspects.