“If you want to go back [home], you have to pay back the money we spent to bring you here.”

“Atiya Z.” (not her real name) and I were sitting under a veranda, shaded from the hot sun in Dar es Salaam, the commercial capital of Tanzania, when she recounted the words that sealed her fate. Atiya told me that in June 2015 she had travelled from her village in Kondowa to Oman for a job as a domestic worker to earn enough money to start a new line of business “for a better life” for her and her six-year-old daughter.

But when she arrived, her employer confiscated her passport and phone, forced her to work 21 hours a day with no rest and no day off; did not allow her to eat food without permission; and beat her every day. After three weeks of enduring this nightmare she tried to flee only for her employer to catch her and bring her back, telling her that the only way she could leave is if she paid them 2 million TZS (US $880).

Atiya said her employer confined her to the house after that. In April 2016, Atiya fell ill and said her employers stripped her naked and beat her with plastic hangers, and her male employer then raped her anally, to punish her. They then took all the money she earned and put her on a flight back to Tanzania the next day: “I was scared, traumatized, and didn’t know who to speak to.”

I spoke to 50 Tanzanian women who worked as domestic workers in Oman or the United Arab Emirates for a Human Rights Watch report issued in November 2017. The majority had migrated to Oman. Many domestic workers find families that treat them well and pay them in full and on time. But I spoke to women who described a far bleaker reality.

Almost all said their employers and agents confiscated their passports. Most worked 15 to 21 hours a day without rest or a day off. More than half said they were paid less than promised or not at all. Many said their employers gave little food, scraps left over from family meals, or starved them as punishment. Most described their employers humiliating them, shouting at them daily and making racial insults. Almost half also said their employers physically assaulted them: pulling their ears, and beating them with sticks and mops.

Nineteen women also described sexual abuse by male family members who groped them, exposed themselves, and chased them around the house. Several described attempted rapes. Some of these cases, like Atiya’s, amounted to forced labor or trafficking into forced labor, which is prohibited in Oman. We documented similar abuses of migrant domestic workers from different nationalities in a previous report on Oman from 2016.

There are more than 154,000 female migrant domestic workers in Oman, according to official Omani statistics from November 2017. They cook, clean, and care for families while in turn hoping to school their children, build homes, or start businesses.

While most domestic workers in Oman come from countries like the Philippines, Indonesia, and India, there are thousands of Tanzanian domestic workers too. Oman has a special relationship with Tanzania, particularly Zanzibar which it once ruled, and the two countries are tied together following centuries of intermarriage, familial and social relationships. Yet, the special relationship has done little to warrant better treatment for Tanzanian domestic workers, and their plight has largely evaded scrutiny.

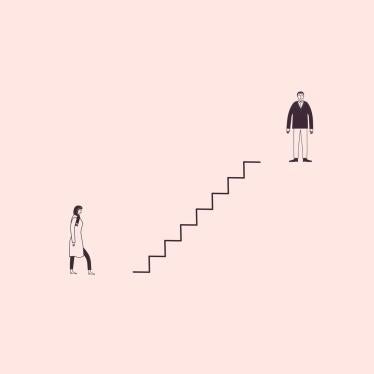

We found that Tanzanians were left more vulnerable from the start because of the Tanzanian government’s failure to provide effective oversight of recruitment agents that charged domestic workers fees or deceived them about their working conditions. After migrating, it is Oman’s laws and systems that essentially allows employers to overwork, underpay, and abuse domestic workers.

Oman’s abusive kafala (sponsorship) system, in force in many Gulf states, ties migrant domestic workers’ visas to their employers and prohibits workers from changing jobs without their current employer’s permission. Workers risk imprisonment and deportation for “absconding” if they leave, even if they are fleeing abuse.

Some workers said their employers or agents forced them to forego their salaries as a condition for their “release,” work for a new employer who repaid recruitment costs to the initial employer, or work unpaid for months in return for flight tickets home or to recoup recruitment fees. Police and Manpower Ministry officials sometimes abet efforts by employers to recover their costs from their workers who fled abuse.

Other Gulf states have begun to tinker with the kafala system. The UAE for instance allows domestic workers to change employers without permission after they complete their contract, Saudi Arabia allows workers to change employers without permission in certain abusive conditions, and Qatar allows workers to change or leave employers who have breached their contracts. But Oman has yet to make real reforms. The Oman Manpower Ministry in a response to Human Rights Watch in November 2017, said that it was studying alternatives to the system.

Oman is also now the last Gulf state yet to provide legal protection for domestic workers’ rights. Bahrain included domestic workers into its labor law in 2012, albeit excluded them from its main protections. Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and more recently in 2017, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates have issued specific legislation for domestic workers. Oman however not only excludes domestic workers from its labor law, but its 2004 domestic worker regulations do not provide effective rights protections, penalties for their breach, or adequate complaints mechanisms.

Furthermore, some Tanzanian domestic workers, like other domestic workers, described how when they fled abuse, the police in Oman not only failed to help them, but charged them with “absconding” for violating the kafala system, or returned them to their employers. At best, they allowed them to leave the country but did not offer them the opportunity to file a criminal complaint. “Hidaya Z.,” for instance, said she went to the police for help in 2016 after a male family member sexually assaulted her but, she said the police told her to pay 200 OMR ($520) or spend three months in jail because her employer reported her for “absconding.”

Of the three Tanzanian workers interviewed by Human Rights Watch who went to the Omani Ministry of Manpower, one said the agent did not turn up to dispute resolution sessions, and the other two said that officials did not believe their stories of abuse and sided with employers. “Basma” for instance, said despite describing her abusive conditions, which amounted to forced labor, to a Manpower Ministry official mediating, he told her that they could not believe her account as they were not there, and instead recommended to Basma’s employer to report her to the police if she refused to pay back the recruitment costs, or work for a new employer who could pay for it.

These accounts also tally with reports by embassy officials in Oman who told Human Rights Watch in 2015 that they did not advise domestic workers to complain to the Manpower Ministry because the ministry officials did not believe them, and because the dispute-settlement department had no power to force employers or agents to attend the sessions or comply with their resolutions.

Having abusive systems and laws is bad for employers too, not just domestic workers. As experienced and skilled domestic workers find themselves trapped to abusive employers, they cannot leave them for better employers in Oman. Instead, some employers are forced into bartering with original employers on the price to “release” them.

The system also enables some good employers to begin to adopt abusive practices. They may come to believe that they should prevent workers from running away by adopting certain practices such as confiscating passports—a common practice—restricting phone calls, confining them to the house, denying them a rest day, or even withholding their pay. Unrealistic expectations that domestic workers can service large extended families, clean multiple houses, or remain at the beck and call for the most minute of tasks--“they drop a spoon on the floor and they call you to pick it up wherever you are in the house”—leave domestic workers overworked and employers disgruntled. Employers may even believe that domestic workers must be bullied into working harder or faster through shouting, insulting and even beatings.

Not only is this abusive, such conditions can more likely lead to workers fleeing. Domestic workers I spoke to have described wanting to work and earn a living in decent conditions, it is often finding out that their conditions are less than promised, and when they are overworked or abused, that they risk escape. Moreover, no one should be seeking to create an environment of fear, intimidation, and violence, in their home.

Oman should reform its kafala system to allow migrant domestic workers to leave and change employers without permission, and introduce legal protections to guarantee domestic workers rights. Employers should also be trained on providing decent working conditions which would not only protect workers but increase more healthy and long-term employment relationships. Domestic workers like “Atiya,” “Hidaya”, and “Basma” deserve to earn their promised salaries with decent working conditions.

As families in Oman increasingly rely on domestic workers, Oman should in turn make sure that domestic workers rights are made a reality.