Summary

I would start working at 4:30 a.m. and finish at 1 a.m. For the entire day they wouldn’t let me sit. I used to be exhausted. There were 20 rooms and over 2 floors. He wouldn’t give me food. When I said I want to leave, he said, “I bought you for 1,560 rials (US$4,052) from Dubai. Give it back to me and then you can go.”

—Asma K., a Bangladeshi domestic worker, in Oman, May 2015

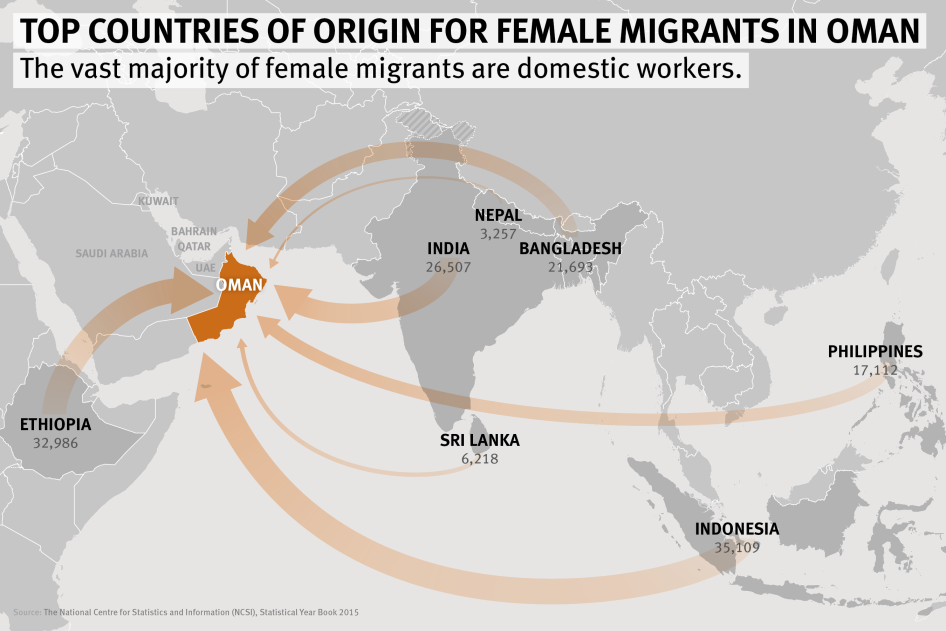

Many families in Oman, like other Gulf states, rely on migrant domestic workers to care for their children, cook their meals, and clean their homes. At least 130,000 female migrant domestic workers—and possibly many more—are employed in the country.

Many workers leave families in Asia and Africa—including the Philippines, Indonesia, India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, and Ethiopia—after recruiters promise them decent salaries and good working conditions. For some workers, these promises are realized.

But for others, the reality is bleak. After they arrive, many find themselves trapped with abusive employers and forced to work in exploitative conditions, their plight hidden behind closed doors.

Based primarily on interviews with 59 female domestic workers in Oman in May 2015, this report documents the abuse and exploitation some migrant domestic workers experience during their recruitment and employment, and the lack of redress for such abuse. It also examines the ways in which Oman’s legal framework facilitates these conditions. In some cases, workers described abuses that amounted to forced labor or trafficking, including across Oman’s porous border with the United Arab Emirates (UAE). While this report does not purport to quantify the precise scale of these abuses, it is clear that abuses are widespread and that they are generally carried out with impunity.

Most of the workers we interviewed said their employers confiscated their passports, a practice that appears to be commonplace even though Oman’s government prohibits it. Many said their employers did not pay them their full salaries, forced them to work excessively long hours without breaks or days off, or denied them adequate food and living conditions. Some said their employers physically abused them; a few described sexual abuse.

Instead of protecting domestic workers from these abuses, Oman’s laws and policies make them more vulnerable. In fact, Oman’s legal framework is often more effective in allowing employers to retaliate against workers who flee abusive situations than in securing domestic workers’ rights or ensuring their physical safety. The country’s immigration system prohibits migrant workers from leaving their employers or working for new employers without their initial employers’ consent and punishes them if they do. Oman’s labor law excludes domestic workers from its protections, and those who flee abuse have little avenue for redress.

The situation is so dire for many domestic workers that some countries, such as Indonesia, have banned their nationals from migrating to Oman for domestic work. However, such wholesale bans are ineffective, and can put women at heightened risk of trafficking or forced labor as they and recruiters try to circumvent the ban. Several countries, like the Philippines and India, have set basic protections for their domestic workers in Oman that Omani law does not provide, such as minimum salaries. But they can do little to enforce these protections once their nationals are in the country.

Oman also at times bans domestic workers coming from some countries. According to a news report, in 2016 the authorities banned workers from Ethiopia, Kenya, Senegal, Guinea, and Cameroon, on the dubious grounds of preventing “the spread of diseases from these African countries to Oman”and because it said workers from these countries “get involved in certain crimes.”

Female migrant domestic workers face multiple forms of discrimination and arbitrary government policies: as domestic workers, they are excluded from equal labor law protections guaranteed to other workers; as women, regulations provide that they can be paid less than male domestic workers; and as migrants, their salaries are based on their national origin rather than their skills and experience. These policies and practices violate Oman’s obligations under human rights treaties it has ratified, including the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women and the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination.

Oman has made a number of reforms to its labor law in recent years and is reportedly considering further revisions, possibly including the extension of its protections to domestic workers.

Abuses against Domestic Workers

Oman criminalizes slavery and trafficking, but enforcement is weak. Forced labor is punished under the country’s labor law, but domestic workers are excluded from that law’s protections. Omani authorities have prosecuted a few individuals for forced labor, but it is unclear whether any of those cases involved domestic workers.

Some domestic workers told Human Rights Watch that employers and agents trafficked them into Oman from the UAE which has a border with Oman. According to embassy officials of several countries of origin, many domestic workers in Oman are brought across the border, eluding regulations or tracking by home embassies. Considering the high number of reports of women trafficked into forced labor situations from the UAE to Oman, the number of prosecutions and convictions for such crimes is strikingly low—there were only five sex trafficking prosecutions in 2015, and none on forced labor.

Recruitment agents promise domestic workers decent working conditions in Oman, and many sign contracts stipulating good salaries before leaving their home countries. But upon arrival, many find that they have to work for less pay than promised and under worse conditions.

Several workers described conditions that amount to forced labor under international law. Many described employers beating them, withholding their salaries, threatening to kill them, falsely accusing them of crimes when they sought to leave, or retaliating against them by beating them for trying to escape abuse. Several workers said that their employers behaved as though they owned them—claiming that the recruitment fees they paid to secure workers’ services were in fact a price paid to acquire them as property. Oman’s legal framework facilitates abuse of domestic workers to such a degree that it could leave some trapped in situations that amount to slavery under international law.

Roughly one-quarter of the domestic workers Human Rights Watch interviewed said that their employers physically or sexually abused them, including a Bangladeshi domestic worker who said that her employer cut her hair and burned her feet, and another who said that her employer’s son raped her. Most said their employers verbally abused them by shouting at them, threatening to kill them, or calling them insulting names like “bitch.” Marisa L., a Filipina domestic worker, recounted: “Madam would say all the time that I don’t have a brain. That I’m dirty.”

Many domestic workers said that their employers delayed paying their salaries or paid less than was owed. Some did not pay their wages at all. One worker said she did not receive wages for a year. Almost all domestic workers complained of working long periods of up to 15 hours per day and, in extreme cases, up to 21 hours per day with no rest and no day off, even if they were sick or injured. For example, Babli H., a 28-year-old Bangladeshi domestic worker, said her employer made her work 21 hours a day with no rest and no day off. She said that her employer also physically and verbally abused her, and withheld two months of her salary. She said when she asked to leave, her employer said, “If the agent doesn’t give me back my money, I won’t let you go.”

In some cases, women worked for large, extended families or in multiple houses. Parveen A., a Bangladeshi domestic worker, said she worked for a family of 15 in 4 houses in their compound in Sohar, a port city in northern Oman. She said she worked for 16 months from 4 a.m. until midnight with no day off. She said her employer only paid her 50 Omani rials a month ($130), 20 rials less than she was owed, and withheld 4 months’ salary entirely.

Domestic workers described common employer practices that kept them isolated from sources of support, namely passport confiscation, tight restrictions on communication, and confinement in the household. While Oman prohibits employers from confiscating workers’ passports, it is not clear whether the law actually allows for criminal sanctions or whether any have ever been imposed.

Under contractual terms mandated by Oman’s government, employers are required to provide domestic workers with adequate room and board; these provisions are particularly important given that many domestic workers are not free to leave their employers’ homes, are not paid in full and on time, and, in many cases, do not earn enough to provide their own food and lodging. Yet some domestic workers said their employers gave them insufficient or spoiled food, and berated or beat them if they requested more. Mamata B., a Bangladeshi domestic worker, said her employer punished her after she fled to the police for help but they returned her. “My madam beat me up and locked me in the room for eight days with only dates to eat and water to drink,” she said.

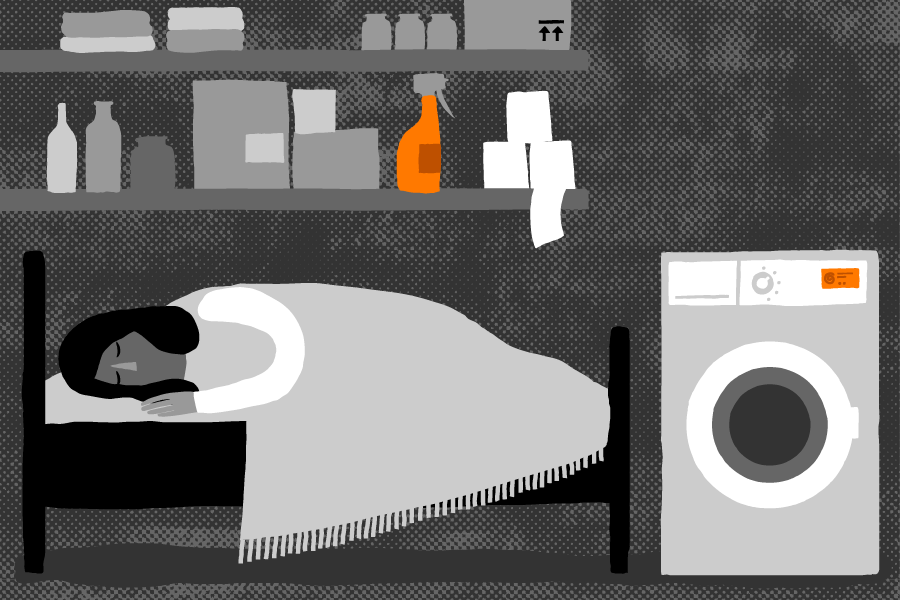

Some domestic workers described inappropriate and inadequate sleeping conditions in their employers’ homes, including in kitchens, living rooms, or with small children. Anisa M., a Tanzanian domestic worker, said, “I sleep in the kitchen. I don’t have a room.”

Punishing Escape and Barriers to Redress

Domestic workers who flee their employers due to abuse have very few options for physical or legal protection. While the government provides some limited shelter services for women subjected to trafficking, very few victims are referred by the government for shelter services, with only five victims provided shelter in 2015. Moreover, the authorities have not established any official emergency shelter specifically for domestic workers exposed to abuse. Some embassies provide shelter and assistance to their nationals, but many do not. Even those that do lack sufficient capacity and adequate conditions. Some workers said when they reported abuse to their recruitment agencies, agents confined them, beat them, and forced them to work for new families against their will.

Domestic workers seeking assistance or justice following abuse are given little help—and may even be punished. Some domestic workers who turned to the police for help said officers simply returned them, against their will, to their employers or recruitment agencies. They said the police did not follow up, and in several cases, domestic workers said their employers beat them after the police sent them back.

Some domestic workers avoided the police altogether, stating that they feared prosecution. This is an entirely reasonable fear, because employers can report domestic workers who flee abusive situations as having “absconded,” an administrative offense under Oman’s abusive kafala system that can result in deportation and a ban on future employment. For instance, Aditya F., an Indonesian domestic worker,fled her employer following physical and verbal abuse, but her employer reported her as “absconding.” The police caught her and returned her to her employer, who beat her and broke her teeth. Some workers said their employers filed, or threatened to file, trumped-up theft charges against them when they asked for their salaries or fled abuse.

Oman’s labor dispute settlement procedures are inadequate and the courts are not a practical avenue for redress for domestic workers. Some country-of-origin embassy officials told Human Rights Watch that they discouraged domestic workers from using these mechanisms because the process is lengthy, unlikely to succeed, and because the women are not legally allowed to work in the meantime. Many workers simply give up and return home unpaid and without justice.

Legal Framework

Oman, like its Gulf neighbors and across the Middle East to varying degrees, implements the notorious kafala (visa-sponsorship) system. Under this system, all migrant workers—who make up almost half of Oman’s population of 4.4 million people—are dependent on their employers to enter, live, and work legally in Oman as they act as their visa sponsors.

Employers have an inordinate amount of control over these workers. Migrant workers cannot work for a new employer without the permission of their current employer, even if they complete their contract and even when their employer is abusive. Moreover, employers can have a worker’s visa canceled at any time. Workers who leave their jobs without the consent of their employer can be punished with fines, deportation, and reentry bans.

In 2011, Oman told the UN Human Rights Council that it “is researching an alternative to the sponsorship system, but this process is not yet complete.” As far as Human Rights Watch is aware, however, the government has not put forward any concrete proposals in the intervening years.

Oman is also reportedly considering revisions to its labor law. In May 2015, the Times of Oman quoted a Ministry of Manpower official stating that Oman is considering extending the law’s protections to include domestic workers. At present, Oman’s labor law explicitly excludes domestic workers from important protections enjoyed by workers in other sectors, such as limits on working hours and provisions for overtime pay. Instead, domestic workers only enjoy a much narrower range of basic protections under regulations issued in 2004 that specifically pertain to domestic workers.

Omani authorities issued a standard employment contract for domestic workers in 2011, which mandates one day off per week and thirty days of paid leave every two years. However, these provisions fall far short of the protections offered by Oman’s labor law and in any case, domestic workers have little ability to enforce employers’ contractual obligations. The contract also provides less than many workers are promised when recruited in their home countries, and falls far short of international standards.

Labor inspectors have no mandate to check on domestic workers, and as such, there are no inspections for working conditions of domestic workers in private homes.

Where Oman has failed to provide adequate protection to migrant domestic workers, some countries of origin—such as India and the Philippines—have attempted to help address this gap by securing some basic protections for their nationals. For instance, some have set minimum salaries for their nationals working in Oman, and have taken steps to blacklist abusive recruitment agencies and employers. However, these are no substitute for strong government action by Oman and in any event, some country-of-origin governments make no efforts to protect their nationals at all. Some recruiters seek out “cheaper” workers from countries with less regulation.

Oman’s International Obligations

The Omani government is obligated under international human rights and labor treaties to address and remedy abuses against migrant domestic workers. However, in breach of these standards, Oman has, like other Gulf states, failed to adequately protect domestic workers against exploitation and abuse. Indeed, in some respects the country’s legal framework facilitates abuse.

The International Labour Organization (ILO) and many United Nations human rights experts and bodies have called on Gulf countries, including Oman, to end the kafala system and grant domestic workers full labor law protections.

Oman should act now to reform its labor law to provide equal protections to domestic workers. It should also reform the kafala system to fully and effectively protect all migrant domestic workers in the country in line with international standards. Oman should cooperate with countries of origin to prevent abuse and exploitation of domestic workers, and should thoroughly investigate abuses and prosecute those responsible. It should ratify key international treaties, including the ILO Domestic Workers Convention, and bring its laws into compliance with their provisions.

Key Recommendations

To the Government of Oman

- Reform the kafala sponsorship system by amending the Foreign Residency Law and its implementing regulations and other laws so that domestic workers can terminate and transfer employment, at will and without employer consent, before and after completion of contract. Remove "absconding" provisions in existing laws.

- Pass a law explicitly criminalizing passport confiscation by employers and agents.

- Ensure that reforms to the Labour Law include expanding the law’s scope so that all of its protections include domestic workers, and update the 2004 regulations on domestic workers to bring them and the Labour Law in line with the ILO Domestic Workers Convention.

- Criminalize forced labor under the penal code with adequate penalties, and thoroughly investigate and prosecute cases of forced labor, slavery, and trafficking.

- Ratify the ILO Domestic Workers Convention and the Protocol of 2014 to the ILO Forced Labour Convention, 1930.

- Establish government-sponsored shelters for domestic workers fleeing abuse or provide financial support for private shelters; and publicize the existence and contact information of shelters and other assistance among domestic workers.

- Train police officers on receiving and processing domestic worker complaints.

- Instruct police officers not to return domestic workers to employers or recruitment agencies against their will, and to thoroughly investigate all credible allegations of abuse against employers and recruitment agents.

- Coordinate with the United Arab Emirates on investigating situations of trafficking of persons, with a particular focus on the role of recruitment agencies in the towns of Al Ain and Buraimi.

- Raise awareness of both domestic workers and employers of rights and responsibilities, and regularly inform employers of penalties for mistreatment.

To the Governments of Countries of Origin

- Provide domestic workers information on their rights, on how to understand and effectively navigate Oman’s legal framework regarding domestic workers, and on how to access crisis support and legal assistance available to them in Oman.

- Report allegedly abusive employers and recruitment agencies to the Omani authorities, so they can investigate and prosecute where appropriate.

Methodology

This report is based on research conducted in Oman in May 2015 by two Human Rights Watch researchers. They conducted interviews in Muscat, the Omani capital, and Seeb, a nearby coastal city, which have high concentrations of recruitment agencies and families employing domestic workers, and where many domestic workers fled after abuse by employers from other parts of Oman.

Human Rights Watch researchers interviewed 59 female migrant domestic workers between the ages of 19 and 52. The workers were from Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, the Philippines, Tanzania, and Uganda. The interviews took place in a variety of locations including parks, open spaces, malls, cafes, hotels, and informal shelters. The researchers conducted interviews in person, and one by phone.

The researchers took care not to approach women in the presence of their employers. The length and depth of interviews varied depending on the degree of privacy at the interview location. Researchers conducted most interviews individually, although some were group interviews.

Human Rights Watch researchers discussed with all interviewees the purpose of the interview, the ways the information would be used, and its voluntary nature. No compensation was provided to interviewees for participating. The researchers also advised all interviewees that they could decline to answer any question or end the interview at any time, and they sought to minimize the risk of further traumatization of those interviewees who had experienced physical or sexual abuse.

Researchers conducted interviews in English, Hindi, Bengali, and Arabic. Whenever possible, interviews were conducted in the workers’ own languages, sometimes with the assistance of an interpreter. Human Rights Watch researchers also interviewed lawyers, country-of-origin embassy officials, and community social workers who requested anonymity.

This report uses pseudonyms for all workers and withholds names for all other individuals in the report who requested anonymity in the interest of their privacy. Interview locations and other identifying information has also been withheld where interviewees requested it.

Human Rights Watch requested meetings with Omani government officials in May 2015. However, the Oman Human Rights Commission informed Human Rights Watch that the government would not grant such meetings, and requested that Human Rights Watch not conduct research in Oman without prior government agreement. Human Rights Watch sent a summary of its research findings and a request for information on domestic worker policies and practices to the Ministries of Manpower, Justice, Legal Affairs, and Foreign Affairs as well as the Royal Oman Police, and the Omani ambassador to the USA in June 2016. None had responded at the time of writing.

Human Rights Watch makes no statistical claims based on these interviews regarding the prevalence of abuse against the total population of domestic workers in Oman.

I. Background

Since the 1973 oil boom, Oman has become a high income economy with a gross domestic product (GDP) of US$52.2 billion in 2015, and gross national income (GNI) of $18,340 in 2014.[1] While not as wealthy as its Gulf neighbors, it is a major destination for migrants from many parts of the world, particularly South Asia.[2]

According to the Omani National Centre for Statistics and Information (NCSI), there are more than 2 million non-Omani nationals in the country, comprising almost half of Oman’s population of 4.4 million people.[3]Migrant workers constitute more than 88 percent of Oman’s private sector workforce, according to a 2015 NCSI report.[4] Oman is one of the top 20 countries from which migrant workers, including domestic workers, send remittances home.[5] In 2014, such remittances totalled $10.3 billion, comprising 12.6 percent of Oman’s GDP.[6]

In 2014, according to government data, 130,006 out of 160,998 migrants employed as domestic workers in Oman were female (over 80 percent).[7] However, this number is believed to be higher as it does not include undocumented domestic workers. Oman’s domestic workers are mostly recruited from the Philippines, Indonesia, India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Ethiopia, and Tanzania.[8] However, there is an increasing recruitment of domestic workers from East African countries to the Gulf states, including Oman, as recruitment agencies attempt to sidestep restrictions and bans in recent years by some Asian countries on domestic workers migrating to the Gulf.

Women seek to migrate abroad for domestic work for a variety of reasons. Many female domestic workers come—in some cases, even for decades—to support family members at home. They are sometimes the sole earner for their family and have few employment opportunities at home. Some hope to build houses for their family or invest in businesses. While domestic workers often take care of their employers’ children, they usually go without seeing their own children for years. Rupa K., a 52-year-old domestic worker from Tamil Nadu, India, said she started working for an Omani family 24 years ago, helping to care for a family while her own 3 children grew up without her in India. Now adults in their 30s, they have children of their own, whom she sees every 2 years. She continues to work in Oman to help her daughter provide for her 3 children aged 5 to 7 because her son-in-law is blind and has not had work opportunities. “I have to support them,” Rupa said. When Human Rights Watch interviewed her she was using her wages to finance the construction of a house for her family.[9]

Others migrate after they find themselves in dire financial straits. Latika C., a 30-year-old Bangladeshi domestic worker, said she migrated because of family debt. “My husband is paralyzed. I had to pay $10,000 in Bangladesh for his operation. We fell into debt because of this and so I decided to travel.”[10] Some women migrate to escape not just poverty but also violence. Marisa L., a 36-year-old Filipino domestic worker, is separated from her husband and the sole supporter of 3 sons and 2 daughters aged between 8 and 21 years old. “I was made to marry the man who raped me. He used to beat me. I came here in Oman for work and my children.”

Many Omani and expatriate households depend on migrant domestic workers. According to a 2013 government report, 23 percent of Omani families employ domestic workers, as do 2 percent of emigrant families.[11] Though these numbers may be higher as they do not include families who are not the sponsors of—but employ—domestic workers.

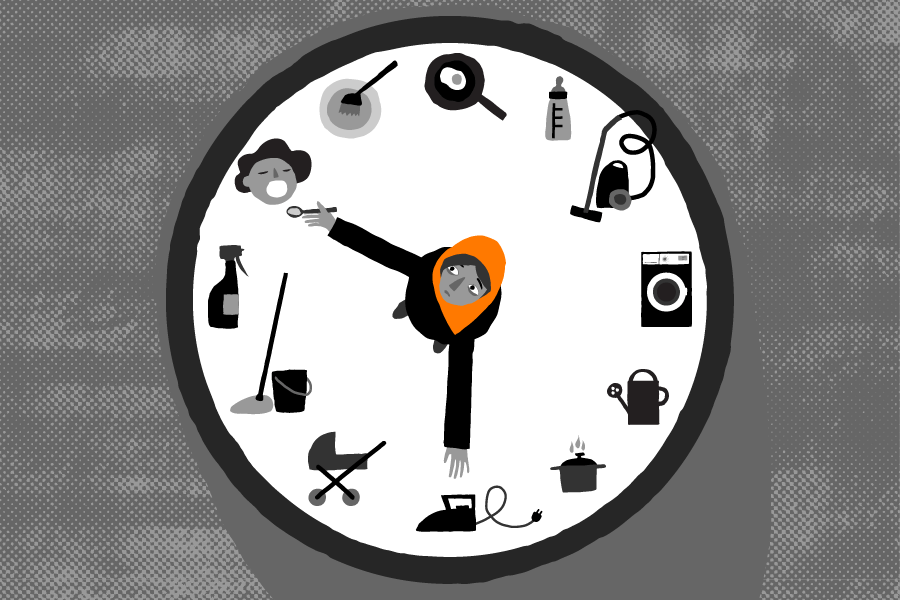

Domestic work, usually considered women’s unpaid work, is often given little respect as real work, a prejudice that is clearly reflected in Oman’s legal framework. Yet domestic workers perform a wide range of vitally important tasks for their employers including: cleaning rooms, windows, and cars; washing and ironing clothes and other laundry; cooking meals; taking care of children, elderly, or individuals with disabilities or special needs; tending to pets, sheep, and goats; and gardening.

II. Abuses against Domestic Workers

This section documents how numerous employers and recruitment agents have abused and exploited domestic workers in Oman. It includes the accounts of domestic workers who experienced forced labor, trafficking, and possible situations of slavery. It also describes a range of other abuses, including: physical, sexual, and psychological abuse; wage abuses, excessive work, and lack of rest; passport confiscation and violations of freedom of movement; and denial of food, rest for illness, and adequate living conditions.

Forced Labor, Possible Situations of Slavery, and Trafficking

Oman has banned forced labor, trafficking, and slavery. However, the cases below show that forced labor and trafficking continue to take place, and possibly situations of slavery, fuelled in part by the government’s immigration policies, notably its reliance on the kafala system. Oman’s legal framework does not address these abuses in accordance with international standards and Oman excludes domestic workers from the protections of its labor law. Even where abuses against domestic workers do contravene Omani law, there is an apparent dearth of prosecutions or other effective enforcement (see chapter III).

Forced Labor

The International Labour Organization (ILO) describes forced or compulsory labor as “all work or service which is exacted from any person under the menace of any penalty and for which the said person has not offered himself voluntarily.”[12]

Many of the domestic workers interviewed by Human Rights Watch in Oman described abusive situations that could amount to forced labor. Most said their employers confiscated and held their passports. Some workers described involuntarily entering or remaining in domestic work. Some also said that their employers told them they could leave only if they first paid back the recruitment fees employers had paid in order to secure their services—in general amounting to about 1,000-1,500 Omani rials (approximately US$2,600-$3,900)—an impossible task for many who said their employers failed to pay their wages in full or on time.[13]

Workers also described a range of situations in which they worked under menace of penalty, an aspect of forced labor. This included situations where their employers threatened to inflict physical violence or kill them; beat them; physically confined them in the workplace; imposed financial penalties, including withholding salaries arbitrarily; threatened to or reported them to authorities as having “absconded” or otherwise breached the kafala system; threatened them with deportation; or falsely accused them of crimes.

Latika C., a 30-year-old Bangladeshi domestic worker, first went to the UAE for domestic work in October 2014. There, an agent took her to a recruitment agency in Al Ain. Shortly after, an Omani man hired her, and took her to Oman for domestic work. She said her employers did not pay her salary for 5 months, beat her when she asked to be paid, confiscated her passport, and made her work 15 hours a day with no rest or day off. They falsely accused her of a crime after she asked for her money. “I asked for my money and they beat me,” Latika said. “Madam said, ‘Tomorrow, we will make a case against you.’” The police then arrested her after her employers accused her of theft (see chapter IV: Absconding Charges and Employer’s Criminal Complaints).[14]

Like Latika, many other domestic workers experienced multiple abuses that together amount to situations of forced labor.

Evelyn S., a 42-year-old Filipina domestic worker, found successive employment with two families in Oman, for around two months each. Both families confiscated her passport; made her work 16 hours a day with no rest and no day off; deprived her of adequate food; and reneged on their promises to pay any part of her 120 OMR ($310) salary per month. She said that members of the second family also verbally and physically abused her, including while she carried hot pots of food. “Mother of sponsor hit me and [I] dropped the pots, which burned my arms,” she said.[15]

Babli H., a 28-year-old Bangladeshi domestic worker, said, “My agent bought me for 80,000 taka ($1,020).” She said her employer in Oman confiscated her mobile phone and passport; made her work 21 hours a day with no rest or day off; physically and verbally abused her; and did not pay her salary for the entire 2 months she worked. She said when she asked to leave, her employer said, “If agent doesn’t give me back my money, I won’t let you go.” She said her employer beat her and kicked her out of the house when the water bill went up—after she watered the garden every day, as her employer ordered.[16]

Possible Situations of Slavery

Situations of slavery are distinguished by the exercise of “any or all of the powers attaching to the right of ownership” over a person.[17] All states have adopted laws that prohibit slavery, but it is widely accepted that the definition of slavery under international law encompasses situations where one person is able to exercise de facto powers of ownership over another in spite of these prohibitions.[18] The UN special rapporteur on contemporary forms of slavery has asserted that slavery includes situations where “the perpetrator puts forward a claim to ‘own’ the victim that is sustained by custom, social practice or domestic law.”[19] There is, however, no clear consensus as to precisely what combination of factors allow for a situation to be properly defined as slavery, as opposed to forced labor, servitude, or slavery-like conditions, under international law.[20]

Human Rights Watch has argued that some countries’ legal frameworks make it possible for migrant domestic workers to become trapped in situations of de facto slavery.[21] The same risk exists in Oman. In light of some of the experiences migrant workers described, Human Rights Watch believes that Oman’s legal framework, in combination with the government’s lax enforcement of the country’s already inadequate legal protections, risks giving rise to situations of slavery.

This report details how Oman’s legal framework facilitates abuse of migrant domestic workers. It helps enable situations where migrant domestic workers are physically confined to the homes they are made to work in, left unpaid, subjected to physical or emotional abuse, cut off from all outside contact, and unable to secure respect for any of the minimal rights they are entitled to under Omani law. In addition to all this, several workers said that their employers also behaved as though they owned them—claiming that the recruitment fees they paid to secure workers’ services were in fact a price paid to acquire them as property. Some employers reportedly told workers that they had “bought” them and that they would not allow them to leave their employment unless that money was repaid.

The mere assertion of ownership rights does not make for a situation of slavery, and Omani law certainly does not recognize any such claim of ownership. But Human Rights Watch documented several cases in which police personnel are alleged to have returned workers who fled situations of confinement and abuse to their employers against their will. As reported to Human Rights Watch, the employers in these situations appeared able to secure the cooperation of law enforcement agencies in ensuring the forcible return of workers who they claimed as property—suggesting the de facto exercise of something akin to “powers attaching to the right of ownership.” Situations like those described below are at the very least dangerously close to situations of slavery.

Human Rights Watch interviewed several workers who said that they fled abusive situations and then either sought assistance from or were detained by the police, only to be returned to their employers against their will (see Chapter IV: Absconding and Police Behavior). Others who sought assistance from their recruitment agencies said they were either returned to their employers against their will or forced to work for another employer unless they could pay back “fees.”[22]

Mamata B., a Bangladeshi domestic worker, said that in 2015 she paid an agent in Bangladesh 350 OMR ($910) to secure a job as a domestic worker in the UAE with a $200 monthly salary. After a medical test in the UAE revealed a blood disorder, she said her employer returned her to the agency, which took her to their office in Al Ain, where she stayed for 25 days. Then they told her to go with an employer to Oman. She said she did not want to go to Oman, but the agent replied, “die here then.” Her new employer also ignored her pleas not to go, and told her, “I bought you in Dubai.”

Mamata said her employer forced her to work 21 hours a day with no rest and no day off for a family of ten people, including six young children; only allowed one phone call in two months; did not provide enough food; verbally and physically abused her; and paid her nothing.

After two months, she fled to the police. She said the police asked for her employer’s contact details, but she pleaded, “I don’t want to go, they will beat me.” She said the police replied, “They won’t beat you.” The police called her employer, who took her back. She said that her employer then beat her and locked her in a room for eight days with only dates and water. She said she fled again after another severe beating by her employer: “She kicked me and I fell on my chest. She picked up my head by grabbing my hair. They beat me mercilessly. I became numb from all the beating.”[23]

Several women described how their employers bartered over how much they would have to pay for their “release” from their visa-sponsorship, in some cases seeking more money than they paid in fees to recruit them. The Times of Oman also reported a recruitment agent describing the charging of ‘release’ money as “common practice.”[24] Combined with the larger context of coercion and abuse many domestic workers face, this could give rise to situations where employers effectively “sell” a domestic worker they employ to someone else against that worker’s will.

Trafficking

Human Rights Watch interviewed several women who described being trafficked into forced labor situations from the UAE to Oman, often across the border between the towns of Al Ain, in the UAE, and Buraimi, in Oman. Several country-of-origin embassy officials told Human Rights Watch that they cannot track workers migrating or trafficked into Oman via this porous border (see chapter III). Nor can they provide these workers with contract verification or require employers to provide them with health insurance. An Indonesian embassy official said many domestic workers who came to them for help had arrived in Oman from the UAE, sometimes in trafficking situations. The same official said that 60 out of 100 women whom the Indonesian embassy had sheltered in April 2015 had come to Oman by crossing the UAE border.[25]

In late 2013, Human Rights Watch heard similar accounts from domestic worker country-of-origin embassy officials in the UAE. They noted that there were many recruitment agencies in Al Ain and Buraimi and that Omani employers travelled to Al Ain on Fridays to find a domestic worker.[26] One country-of-origin official told Human Rights Watch that women, many of whom had travelled to the UAE to work as domestic workers, were confined to recruiting agency offices or even “put on display” for potential employers.[27] These agency offices reportedly allowed employers from Oman and other Gulf states to find readily available domestic workers when they did not want to spend time processing travel for a migrant domestic worker or wanted to avoid other restrictions. One country-of-origin official noted: “In Al Ain, you see a lot [of agencies] especially on the border. It is just like window shopping.”[28]

Asma K. said she paid 300 OMR ($780) to an agent in Bangladesh to connect her to a job in the UAE. She said a UAE agent picked her up in Sharjah and took her to Dubai, where she said, “I was sold to a man in Oman.” Her employer then confiscated her passport; forced her to work 21 hours a day with no rest or day off for a family of 15; deprived her of food; did not pay her salary; and subjected her to verbal abuse and sexual harassment. When she asked to leave, her employer said, “I bought you for 1,560 rials ($4,052) from Dubai; give it back to me and then you can go.” After his adult sons sexually harassed her, she said, “I begged their mother, ‘Your sons won’t leave me alone at night. Please let me go home.’” Her employer's wife sent her back to the agent. But the agent hit her about 50 times with a stick that night, and sent her to work for another employer.

The new employer was no better. Asma said her second employer forced her to work 20 hours a day with no rest and no day off; confiscated her passport; gave her only leftover spoiled food; did not pay her; and verbally and physically abused her. She said she fled after her employer threatened to kill her: “She tried to cut me with a knife. I begged her not to hit me. I said, ‘Take me back [to the agency].’ She said, ‘I will throw you in the river.’”[29]

Some women are subject to trafficking into forced labor, without going via the UAE. Sushila R., a 21-year-old Bangladeshi domestic worker, said that in 2015 she took a loan to pay 100,000 taka ($1,265) to an agency in order to obtain a customer service job in Oman. But just before she left Bangladesh, she learned that her visa designated her as a domestic worker. She said the agent explained that she would first be taken to a house, and then after two days, her employer would take her to a shop to do customer service work. After arriving, she said she told her employer, “I’m supposed to work in the shop.” But her employer said, “No, you are a housemaid… If you don’t work with me, then I will hit you, and send you back.” She fled the house and went to the police. Sushila said the police sent her back to her agent in Mabella (a coastal area at the edge of Muscat), who told her, “I paid 200 rials ($520). If you pay this, then you can go.” She said she replied, “No, I paid for everything myself.” He beat her and locked her in a room with two other women who said the agent had also “bought” them for 200 OMR. She said she managed to escape after she jumped out of a second-story window and cut her feet.[30]

Physical, Psychological, and Sexual Abuse

Some domestic workers whom Human Rights Watch interviewed said that their employers physically abused them, often if they were not pleased with their housework, including by beating them with sticks; punching, slapping, and kicking them; burning them with hot food, water, and implements; and pulling or cutting their hair. Human Rights Watch observed injuries during interviews such as missing teeth and hair, bruises, and burns.

“Madam would shout at me, and when she thinks that work is not done right she would grab my hair and pull me out of the house,” Husna J., a 20-year-old Bangladeshi domestic worker, told Human Rights Watch.[31] Similarly, Asma K. also from Bangladesh, said her employer would criticize her for not watering the plants correctly. “If I said I did,” Asma said, “she would slap me twice.”[32]

Sometimes, more than one family member meted out abuse. Shima U., a 50-year-old Bangladeshi domestic worker, said that during the six months she worked for an Omani employer in 2014, several family members beat her: “They held my arms and two people beat me. Madam pulled my hair, and burnt me on my arms.”[33]

In other cases, workers said employers beat them for other “transgressions,” like eating food, speaking on the phone, asking for their salary, or asking to quit their job. Parveen A. said her employer beat her when she found her eating rice in the kitchen: “She beat me up. She pulled my hair and hit me all over.”[34] Latika C. said that when she asked her employer for her salary, it “created a storm. They beat me for asking for it.”[35]

Some women described how their employers beat them even more severely after they fled and reported abuse to the police, who sent them back.

Aditya F., a 30-year-old domestic worker from West Java in Indonesia, said her employer beat her and broke her teeth after the police returned her to her employer’s home in 2014.[36] Latika C. said the police returned her to her employer after they cleared her of a theft allegation, and that her employer abused her for two days upon return: “He cut my hair and burned my feet with hot water.”[37]

Most of the domestic workers who spoke to Human Rights Watch said that their employer or members of their household shouted at and insulted them, threatened them, and humiliated them. Many said their employers treated them like “animals,” or as if they were dirty. “Madam would say all the time that I don’t have a brain. That I’m dirty. That I don’t know how to cook. They would call me ‘ayb’ (in Arabic, shameful or disgraceful),” said Marisa L.[38]

Jocelyn E., a 28-year-old Filipina domestic worker, said all eight members of the family she worked for also shouted at her and called her things such as “Filipino bitch” and “crazy.”[39] Rahela C., a Bangladeshi domestic worker, said her employer refused to pay her three months’ salary and threatened to kill her when she asked for it. She said her employer told her, “I will kill you and throw you in the sea.”[40]

Human Rights Watch also interviewed three domestic workers who said that their employers or members of their employer’s household had raped, sexually assaulted, or sexually harassed them.

Asma K. said that her employer’s three adult sons sexually harassed her at night. She said they called her to come to them, and she refused. She said, “I begged their mother, ‘Your sons won’t leave me alone at night. Please let me go home.’”[41] The mother sent her back to the agent.

Marisa L., a Filipina domestic worker, said her employer’s 21-year-old son sexually harassed her in 2012-2013. She said he often got drunk and offered her money to have sex with him. One time, she said, he came into the bathroom while she was cleaning, made sexual gestures at her, and said, “I want you little bit like this and like that.”[42]

Mausumi A., a 30-year-old Bangladeshi domestic worker, said that her employer’s son raped her in 2015: “I was working until late that night. I woke up at 3 a.m. to get something. The 27-year-old son grabbed and raped me.”[43]

Wage Abuses, Excessive Work, and Lack of Rest

Many domestic workers whom Human Rights Watch interviewed said that their employers did not pay their wages, paid them late or less than was owed, and required them to work excessive hours without rest periods or rest days.

Wage Abuses

Some domestic workers told Human Rights Watch that their employers had not paid wages for anywhere from one month to one year. Several said their employers told them they would pay only after a certain number of weeks or months to compel them to stay—and even then, might underpay. Oman’s 2004 domestic worker regulations require that the employer pay monthly wages within seven days of the end of each month, and an employee must sign a receipt for it (see chapter III).[44]

Anandini U., a 36-year-old Indian domestic worker from Andhra Pradesh, said her Omani recruitment agency told her she would receive 120 OMR ($310) per month, but her employer only gave her 80 OMR ($208), always delaying by weeks. “If I ask for salary, they just shout and shout,” she said.[45] Evelyn S. said she signed a contract in the Philippines to do domestic work for 160 OMR ($415), but the two successive families she worked for—in each case for two months—told her they would pay only 120 OMR ($310), then did not pay her at all.[46] Nalini H., a Bangladeshi domestic worker, said her employer paid her 60 OMR ($155) per month for two months of work, but then stopped paying for a full year.[47]

Excessive Work and Lack of Rest

Most of the domestic workers who spoke to Human Rights Watch said their employers required them to work for excessively long periods—15 to 21 hours a day—and carry out a variety of tasks.

Asma K. said her employer made her work from 4:30 a.m. until 1 a.m. without rest. “For the entire day they wouldn’t let me sit,” she said. “I used to be exhausted. There were 20 rooms and over 2 floors.”[48]

Divya S., a 43-year-old Indian domestic worker from Kerala, said she started working at 5 a.m. and would finish between 10 p.m. and midnight. She cleaned, washed clothes, cooked, and ironed. Divya said her employer allowed her to go back to the Omani agency office because it was “too much work. No rest.”[49]

Many domestic workers said their employers did not allow them to rest even if they were ill or injured, including Jocelyn E., who said: “I had the flu and a fever, but they didn’t let me stop working.”[50] Maricel P., a Filipina domestic worker, said, “Because of overwork, I became sick. [Yet] I was allowed to rest for only two hours but [then] had to work.”[51]

Few workers said their employers regularly allowed rest periods during the day or periodic days off. Only two said their employer allowed a weekly day of rest. This is despite the 2011 domestic workers standard contract which requires that employers allow one paid weekly day of leave, or compensation in lieu of time off.[52] Jocelyn E. said she worked from 5:30 a.m. until 10:30 p.m. or later with almost no rest: “If I finish work then [I] can have lunch for 30 minutes.” Her employer did not allow any days off for nearly a year, then allowed only one day off per month for her last five months of work.[53]

Many workers described excessive work demands. Anandini U. said she worked for an Omani family of three, but relatives often visited, and she then worked for up to eleven people. She said she worked from 4 a.m. until late at night cleaning, cooking, and taking care of a baby day and night, with no rest and no day off. “Too much difficulties,” she said.[54] Parveen A. said she worked for a family of 15 in 4 houses in their compound in Sohar. She said she worked for 16 months from 4 a.m. until midnight with no day off.[55] Aisha N., a 22-year-old Ugandan domestic worker, spent 24 months working for an Omani family of 8 including 6 young children. She said she worked 13 to 16 hours a day with no day off.[56]

Passport Confiscation, Restricted Communication, and Confinement

Passport is always with madam.

—Rupa K., 52, an Indian domestic worker, who spent 24 years working for an Omani family.[57]

Domestic workers in Oman described common employer practices, such as passport confiscation, tight restrictions on communication, and confinement in the household, which cut them off from sources of social support.

Almost all the domestic workers Human Rights Watch interviewed said their agents or employers had confiscated their passports. Jocelyn E. said: “When I arrived [in Oman], the agency took my passport and gave it to madam, [who then kept it].”[58] Marisa L. said her Omani employer confiscated her passport upon arrival in 2011: “She told me, ‘Give me your passport and I will give it back to you when you finish your contract.’”[59]

Passport confiscation is a key element in identifying situations of forced labor.[60]

A 2006 circular produced by Oman’s Ministry of Manpower makes clear that employers have no right to retain workers’ passports without their consent or a court order.[61] According to the US State Department, in 2014, the Royal Oman Police placed public awareness announcements in local English and Arabic newspapers to raise awareness that confiscating the passport of an expatriate worker is illegal, and that passport confiscation could lead to prosecution and a jail sentence.[62] However, the 2006 circular provides for no specific penalties for noncompliance.

The Times of Oman reported that a Royal Oman Police (ROP) source said that the “ROP has nothing to do with expatriates’ passport in such matters,” and is only authorized to deal with such cases if an Omani passport is involved. The article also reported that the Ministry of Manpower does not directly sanction employers for passport confiscation, quoting a government official saying, “the Ministry of Manpower tries to settle the issue between the employers and employees,” and refers the issue to the Public Prosecution in the event of failure to do so.[63]

The US Trafficking in Persons Report in 2016 reported that the Ministry of Manpower handled 432 passport retention violations, of which “137 were referred to the lower court, 126 were settled through a mediation process, and seven were referred to labor inspection teams comprised of law enforcement to check on the employer.” But the report noted that the Ministry did not refer any of these violations for criminal prosecution of potential labor trafficking offenses. It did not mention whether any of these cases involved domestic workers or whether employers faced sanctions for passport confiscation.[64]

Human Rights Watch approached several government ministries to ask whether there are any laws that are used to prosecute employers who confiscate domestic workers’ passports without their consent; none responded.

Some domestic workers also told Human Rights Watch that their employers took their phones and refused to let them use household telephones or computers. Babli H. said, “The agent gave me an Omani sim card so I can call my son. But my madam took my mobile. I pleaded with her, ‘Please don’t take my mobile.’”[65] But her employer would not give it back to her.

Nalini H. described how her employer beat her for calling her family:

After a month they wouldn’t give me my phone. I would cry and plead for my phone. My brother had an accident and his legs were injured. I managed to call my brother, but my boss said, “This is not your brother.” They think I have a boyfriend. Then boss, madam, and their daughter beat me with sticks all over my body.[66]

Some women told Human Rights Watch that their employers did not allow them to leave the homes where they worked and even locked them inside. Other domestic workers said that even if they were not locked in, they felt isolated, especially if they lived outside the main cities and far away from their embassy. For workers living in large cities, it can still be hard to know how to get to their embassy, or to pay for a taxi. “I left the house and walked for hours. I was exhausted,” Asma K., a Bangladeshi domestic worker who fled her abusive employer, told Human Rights Watch. She eventually came across a Bangladeshi worker who took pity on her and gave her some cash. “I took four taxis to go to the embassy. It cost me 30 rials ($78),” she said. [67]

Denial of Food and Inadequate Living Conditions

While Oman’s 2004 domestic worker regulations and standard contract makes employers responsible for providing domestic workers with adequate room, food, and medical care, some domestic workers said that they were not provided sufficient food or sleeping conditions.[68]

For instance, some domestic workers told Human Rights Watch that their employers gave them insufficient or spoiled food and berated or beat them if they requested more. This problem is particularly serious because the domestic workers Human Rights Watch interviewed generally lacked the financial means to purchase their own food, and in many cases, the time off work and even the freedom of movement necessary to procure it. Several workers said their employers deprived them of food as a punishment for their “mistakes” in housework.

Evelyn S. said that her first employer in Oman did not allow her to eat lunch. Describing the situation with her second employer she said, “Sometimes I do not eat because there is too much work.”[69] Mamata B. said her employer punished her after she fled to the police for help but they returned her: “My madam locked me in the room for eight days with only dates to eat and water to drink.”[70] Parveen A. said her employer beat her when she found her eating rice.[71]

Some domestic workers also described inadequate sleeping conditions in the homes where they worked. Some said employers required them to sleep in the same room as children, sometimes in the same bed as a child. One worker said she slept with a two-month-old baby, and another said she had to sleep in the same bed as her 45-year-old female employer because she is “madam’s right hand.”[72] Others said they slept in kitchens, storage rooms, or open living rooms. Anisa M., a Tanzanian domestic worker, said, “I sleep in the kitchen. I don’t have a room.”[73]

III. Legal Framework

The acute vulnerability of domestic workers in Oman to abuse and exploitation by their employers is largely attributable to Oman’s badly flawed domestic legal framework. In 2007, the UN Special Rapporteur on trafficking in persons stated that domestic workers in Oman, who are “hidden behind the guarded walls of their employers’ homes” are susceptible to abuse and exploitation because of the restrictive immigration system of kafala and the “weak legal framework surrounding their working conditions.”[74]

The situation that domestic workers face in Oman is similar to that of most countries in the region.[75] In some of these other countries, however, there have been important examples of progress in recent years. Jordan became the first in the region, in 2008, to include domestic workers under its labor law, and adopted domestic worker labor regulations in 2009.[76] Since then, some Gulf governments—faced with frequent reports of worker abuse, country-of-origin complaints, and occasional bans on migration to Gulf countries by countries of origin—have instituted reforms. In 2015, for example, Kuwait adopted a new law specifically covering domestic workers’ labor rights.[77]

Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) labor ministers have discussed the possible development of a regional standard contract for domestic workers, but a draft made public in 2013 failed to provide key protections, such as a limit on hours of work.[78]In November 2014,news mediacited an announcement by a GCC official following a Labor Ministers’ meeting that the GCC had agreed on a new standard contract for domestic workers. It would reportedly have imposed an eight-hour limit on their working day, given them one day off each week, overtime compensation, paid annual leave, and allowed them to live independently from their employers.[79] However, it later appeared that the GCC had not concluded an agreement but instead ministers agreed to check whether their governments would agree on the provisions.[80] Since then it seems that the initiative has been shelved.

While a regional standard contract would not make up for the lack of equal protections for domestic workers under the respective national labor laws of GCC member states, it could be a move in the right direction if it were in line with the ILO Domestic Workers Convention.[81]

Possibilities for regional cooperation aside, Oman has human rights law obligations to improve its own legal framework to ensure that it protects domestic workers’ rights instead of discriminating against domestic workers and facilitating abuses against them as it does now. The following pages describe the most urgently needed areas of legal reform.

Kafala-(Visa-Sponsorship) System

Oman administers a visa-sponsorship system (known as kafala), in which a migrant worker’s ability to enter, live, and work legally in Oman depends on a single employer who also serves as the worker’s visa “sponsor.” Governed primarily by the foreign residency law and reinforced by other laws and regulations, this system gives employers inordinate control over migrant workers and severely limits workers’ ability to escape abusive working conditions. [82] The Royal Oman Police, which also acts as Oman’s immigration authority, enforces the kafala system along with the Ministry of Manpower.

Oman’s 2004 domestic worker regulations also reinforce the restrictive aspects of the kafala system. They stipulate that domestic workers are not allowed to work for another employer until their current employer—also their visa sponsor—has ended their sponsorship and all other required procedures are followed.[83] The labor law, which applies to other types of migrant workers, is also rooted in the kafala system and provides additional penalties for employers and workers who violate its restrictions.[84]

Domestic workers who wish to leave abusive employers before the end of their contract (generally two years) may not transfer to another employer without their current employer’s permission, in the form of a “no-objection certificate” or “release.”[85] The Directorate General of Labour within the Ministry of Manpower must then approve the transfer.[86] According to official data, authorities granted only 119 visa-sponsorship transfers for domestic workers in 2014.[87] This is a low number given that there are some 160,000 domestic workers in Oman, many of whom may want to change employers before their contract ends or after they have completed their contracts.[88] The UN Special Rapporteur on trafficking in persons has criticized this process, stating that: “The fact that approval is needed from the very person the worker wishes to be released from, possibly due to abusive and exploitative conditions, is clearly problematic.”[89]

Ministry of Manpower regulations require that employers pay work-permit and processing fees of approximately 141 OMR (US$365).[90] Private recruitment agencies charge additional fees, including for the worker’s flight tickets and medical tests.

Migrant workers who leave Oman after their contract period are not allowed to re-enter Oman to work for two years.[91] As such, migrant domestic workers who wish to continue working, but for a different employer, must remain in Oman to transfer employers. Even in these cases, they must also obtain a “release letter” from their prior employer.[92]

Several domestic workers recounted how their employers asked them to pay back recruitment fees, including work-permit fees, or demanded more money in return for their approval of a transfer. A March 2016 Times of Oman article quoted a Ministry of Manpower official saying this practice is “unlawful,” but the same article quoted a recruitment agency official referring to this as a “common practice.”[93] Human Rights Watch’s research did not discover any explicit legal prohibition of this practice. We wrote to several government ministries in an effort to confirm this but did not receive a response.[94]

An employer can cancel their domestic worker’s residence permit at any time by initiating repatriation procedures.[95] The 2004 domestic worker regulations only requires that employers should provide one months’ notice.[96] However, when a worker leaves their sponsor before the end of their contract without permission, they are considered to have “absconded” so long as they remain in Oman and can be punished with imprisonment, fines, deportation, and bans (see chapter IV: Absconding Charges). Sponsors can also be punished for not reporting when their workers have “absconded.”[97] Oman’s 2004 domestic worker regulations provide that a domestic worker may terminate employment “if it is proven that he was assaulted by the employer or a member of his family.” But even in this situation, domestic workers still cannot transfer employers without their sponsor’s permission, and face barriers in accessing help following physical abuse (see chapter IV).

The kafala system creates incentives that have led to an informal black market known as the “free visa” system, in which sponsors allow their workers to work for other employers. In return, the worker pays the original sponsor a “fee.” Kani S., an Indonesian domestic worker, said she paid her sponsor 300 OMR ($780) per year, and now lives independently and works for two to three employers, earning a combined income of 260 OMR ($675) per month.[98]

One community social worker noted that some sponsors exploit the “free visa” system by charging high fees and keeping their workers’ passports as leverage. He also said that unbeknownst to the workers, some of these sponsors also report them for “absconding,” so if their worker is caught working for another household, the original sponsor will not be punished.[99]

The restrictive kafala system has also contributed to tens of thousands of foreign nationals residing without legal status in Oman. The Omani authorities periodically grant amnesties to allow them to leave Oman without penalty. In a 2015 amnesty, for example, more than 20,000 foreign nationals reportedly took the opportunity to leave.[100]

Oman has indicated some willingness to reform the kafala system. During Oman’s 2011 “Universal Periodic Review” process at the UN Human Rights Council, the government noted that it “is researching an alternative to the sponsorship system, but this process is not yet complete.”[101] Human Rights Watch is not aware of any concrete proposals that have emerged from this process in the intervening years. In 2016, the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination expressed concern about the kafala system for placing migrant workers “in a highly dependent relationship with their employers,” and called on Oman to abolish it.[102]

Lack of Labor Law Protection

Domestic workers are not covered under Oman’s labor law. Article 2(3) explicitly excludes domestic workers from the law’s purview and therefore also from all of the protections it offers.[103] Oman is reportedly considering a revised labor law, which may include domestic workers.[104] In April 2016 the Times of Oman quoted Salem Al Saadi, an advisor to the Minister of Manpower, stating that Oman has “plans to legalise their rights and provide better protection to domestic workers,” which will be “either in the new labour law or as a separate chapter.”[105]

Oman’s 2004 domestic worker regulations do provide for some loose rules regarding the employment conditions domestic workers should enjoy.[106] It requires employers to provide their domestic workers with monthly wages within seven days of the end of each month; adequate room, board, and medical care; return airfare when the employer terminates the contract; and airfare to and from their home countries during approved vacation days.[107]

However, the 2004 regulations fall short of the rights and protections provided for workers in other sectors under Oman’s labor law. For instance, the regulations do not establish standards for working hours, weekly rest days, annual vacation, or overtime compensation. Nor do they establish that domestic workers can form or join unions, a right that Oman’s labor law affords to workers in other sectors.[108] Moreover, domestic workers do not benefit from the labor inspection system prescribed by the labor law and other regulations, nor from the “wage protection system” involving direct payment of wages into bank accounts, unlike migrant workers in other sectors.[109] The regulations do not stipulate any penalties for employers’ breaches of its provisions unlike the labor law. The regulations only state that a department in the Ministry of Manpower can handle domestic worker employment contract disputes, but as described in chapter IV, there are problems with this form of dispute resolution.[110]

|

ILO Convention concerning Decent Work for Domestic Workers Oman voted in favor of creating the 2011 ILO Convention 189 concerning Decent Work for Domestic Workers, which came into effect on September 5, 2013.[111] Despite this show of support, Oman has yet to ratify the convention.[112] The convention requires governments to provide domestic workers with labor protections equivalent to those of workers in other sectors, covering hours of work, a minimum wage, compensation for overtime, daily and weekly rest periods, social security, and maternity protection. It also obligates governments to protect domestic workers from violence and abuse; regulate recruitment agencies and penalize them for violations; and ensure effective monitoring and enforcement of labor rules relating to domestic workers. |

Excluding an entire category of workers, the majority of whom are women, from equal labor law protections violates Oman’s obligations under the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW). CEDAW requires the elimination of discrimination against women in all areas, including employment.[113]

Despite the labor law’s supposedly gender neutral exclusion of domestic workers, it is clear that women are disproportionately and negatively impacted by this exclusion. Neutral provisions or practices that put persons of one sex at a particular disadvantage compared with persons of the other sex constitute impermissible, indirect discrimination unless that provision or practice is objectively justified by a legitimate aim, and the means of achieving that aim are appropriate and necessary.[114] There is no such legitimate aim for excluding domestic workers from legal protections in Oman.

As domestic workers are foreign nationals, the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination also called on Oman to include domestic workers under its labor laws.[115]

In addition, Omani guidelines for employers imply that male domestic workers should be paid more than female domestic workers. A government “Service Directory” provides that an Omani employer wanting to hire a “non-Omani” laborer to work in a house must earn a monthly salary of at least 350 OMR ($910) to prove they can pay the salary of a single female worker. But for a male worker, the employer’s income must be at least 1,000 OMR ($2,600).[116] This suggests that the Omani authorities expect that a male domestic worker’s salary would be far higher than that of a female domestic worker.

Migrant domestic workers also face wage discrimination on the basis of national origin. The Council of Ministers (the cabinet) has only set minimum wages for Omani nationals working in the private sector.[117] Migrant workers are thus excluded from minimum wage regulations. As there is no minimum wage set for domestic workers, some countries of origin have set minimum wages for their domestic workers which embassies try to check are reflected in the employment contract before workers are allowed to depart. The salaries vary from 70 OMR ($180) to 160 OMR ($415) (see section below entitled Country-of-Origin Protection Mechanisms). Recruitment agencies, in turn, often set minimum pay rates on the basis of a domestic worker’s nationality rather than on experience and skills, or the nature of her work.[118] This is a common practice in other Gulf states too.[119] One country-of-origin official noted that in some cases, agencies even advertise salaries lower than the minimum salaries set by countries of origin.[120] This is not against the law as Oman has no minimum salary set for domestic workers. This practice of setting salaries on the basis of nationality amounts to discrimination as it is unjustified, unequal treatment with no legitimate aim. This is done openly and with no effort to conceal it from the Omani authorities, who have facilitated this kind of discrimination by not setting minimum wages for all domestic workers in violation of their obligations under the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD).[121]

Standard Contract for Domestic Workers

Domestic workers are required to have a contract under the 2004 regulations.[122] In 2011, the Ministry of Manpower issued a standard employment contract for domestic workers.[123] It includes the provisions from the 2004 regulations relating to regular payment, food and accommodation, medical expenses, and return airfare when the contract is terminated.[124] The standard contract, in addition to the regulations, requires that the employer allow one paid weekly day of leave, as well as a 30-day leave (including return flights) every 2 years, or compensation in lieu of either form of leave.[125] It does not set the rate of wages that must be paid to domestic workers.

The standard contract in Oman undoubtedly helps in some respects to promote domestic workers’ rights. But as described in chapters II and IV, these contractual rights are often breached, and remedies are often unattainable. Moreover, the standard contract does not fix the problem of domestic workers signing one contract with better terms in their country of origin, only to have it ignored in Oman. Many Filipina domestic workers, for example, told Human Rights Watch that the initial contract they signed in the Philippines provided that they would be paid 160 OMR ($415) per month, but upon arrival, their employers said they would receive a lower wage, often in the range of 90-120 OMR ($234-310).

The UN Special Rapporteur on trafficking in persons commented about problems with domestic worker contracts in Oman, noting, the “authorities are reluctant to interfere in the contractual relationship between domestic workers and their employers as this relationship is viewed as a private family affair; any interference would be seen as impinging on the family’s right to privacy. This lack of protection, however, impinges on the rights and freedoms of the workers.”[126]

Moreover, according to one lawyer, domestic workers who change employers before completing their two-year contract while in Oman often do not have a contract with their new employer.[127] This is largely because the procedure for transferring to a new employer does not require her to have a standard contract with the new employer.[128]

Country-of-Origin Protection Mechanisms

Given Oman’s lack of labor law protections for domestic workers, and only minimal regulatory protections, governments of countries whose nationals migrate to Oman for domestic work have tried to step in to bolster protections. However, these measures are not always effective.

Several countries of origin, such as the Philippines, require that employers and recruitment agencies agree to a worker’s minimum salary and conditions of employment before the worker will be authorized to migrate. This process requires country-of-origin embassies in Oman to “verify” domestic workers’ contracts by checking that the employer has agreed to a minimum salary and other conditions of employment. Upon doing so, domestic workers are provided an exit permit to leave their country of origin.

The monthly minimum wage that countries of origin require varies. As of 2015, the minimum salaries for some major countries of origin were: the Philippines 160 OMR ($415), Indonesia 120 OMR ($310), Sri Lanka 85 OMR ($220), India 75 OMR ($195), Bangladesh 75 OMR ($195), and Tanzania 70 OMR ($180).[129]

Beyond verifying the minimum salary, some countries of origin require the employer to sign additional undertakings with their embassies for decent working conditions, such as a limit of eight working hours per day.[130] Some also have measures to promote domestic workers’ rights and safety. India, for instance, requires employers to supply a pre-paid mobile phone for the domestic worker.[131] Both the embassies of India and Bangladesh require that employers obtain specific medical insurance for their domestic workers.

However, once a domestic worker is in Oman, countries of origin have little power to enforce these conditions. One of the only practical measures they can take is to “blacklist” recruitment agencies or sponsors in Oman that they believe have abused or exploited workers.[132] If an embassy blacklists an agency or sponsor, it will not verify or approve contracts for future workers to come to Oman with that agency or sponsor.

The Philippines also sanctions agencies in its country whom they deem to have been abusive or deceptive in their recruitment of Filipino domestic workers migrating abroad.[133] Workers can file claims against Filipino recruitment agencies when they return home, although such processes can take months or even years. Indonesia also provides mechanisms for returning migrant workers to seek redress through insurance schemes, administrative dispute resolution mechanisms, or the courts. However, such processes are undermined by a number of barriers that prevent workers from accessing justice.[134]

Some country-of-origin embassies, including India and Sri Lanka, try to guarantee that domestic workers will be paid their salaries by requiring that sponsors provide a security deposit.[135] When the employment contract ends, the embassies interview domestic workers to check whether wages were paid before returning the security deposit.[136]

However, countries of origin cannot provide such protections when domestic workers migrate or are trafficked into Oman through unregulated channels, often via the UAE. In addition, domestic workers who come from countries that do not have an embassy or consulate in Oman, such as Uganda, do not benefit from such protection. Ethiopia, which has a large number of domestic workers in Oman, has an honorary consulate but it is not a full-fledged diplomatic mission that can provide these protection mechanisms for its workers.[137]

Other countries, such as Indonesia, have banned their nationals from migrating to particular countries for domestic work, including Oman, in part due to repeated cases of abuse.[138] However, such bans are ineffective and can put women at heightened risk of trafficking or forced labor as they and recruiters try to circumvent the ban.[139] An Indonesian official said that despite the ban, Indonesian domestic workers still end up in Oman. He said he suspects that about half of the Indonesian domestic workers coming into Oman arrived via the UAE.[140]

Unlike some other Gulf states, the Omani authorities have not prevented countries of origin from conducting contract verification and other such measures to protect their workers.[141] Officials at country-of-origin embassies noted that Omani authorities do cooperate with them at times. For instance, an Indonesian embassy official noted that since the Indonesian government barred its citizens from migrating to Oman to be employed as domestic workers, the Omani authorities had stopped processing visas for Indonesian domestic workers.[142]

Unfortunately, Oman also at times bans domestic workers coming from particular countries. According to media outlets in Oman, the Omani authorities issued a ban effective on February 1, 2016, on domestic workers coming from five African countries including Ethiopia, Kenya, Senegal, Guinea, and Cameroon. Muscat Daily reported that a senior Royal Oman Police official said that they issued the ban to “prevent the spread of diseases from these African countries to Oman,”and because they believed these workers “get involved in certain crimes.”[143] If this is the government policy, Omani authorities risk fueling racial discrimination against workers with these nationalities by depicting them as “diseased” and prone to crime.

Criminalizing and Prosecuting Forced Labor, Slavery, and Trafficking

Oman has banned forced labor, slavery, and trafficking, and offers victims some social services. However, it has done little to address key structural factors that contribute to human rights abuses faced by domestic workers, namely the kafala system and the exclusion of domestic workers from the labor law. It has also done little to ensure accountability or redress for these abuses. Instead, as the cases in chapter II and IV show, women described being punished for escaping abuse, including those that amounted to forced labor and trafficking.

Forced Labor and Slavery

Oman’s Basic Statute of the State (the country’s constitution) prohibits forced labor.[144] The labor law, amended in 2006, also prohibits forced labor, but the penalty is only one-month imprisonment or a fine of 500 OMR (US$1,300).[145] However, it does not apply to domestic workers, as the labor law excludes domestic workers and the 2004 domestic worker regulations say nothing about forced labor.

Oman’s penal code criminalizes slavery and the slave trade, but not forced labor. Article 260 provides, “anyone who enslaves people or puts them in a state similar to slavery” can be sentenced to imprisonment from five to fifteen years.[146] Article 261 provides that anyone “who makes someone enter or leave the territory of Oman in a situation of slavery or bondage or disposes, receives, acquires, or keeps him/her in this position” can be imprisoned for three to five years.[147]

|