(Beirut) – Many migrant domestic workers are trapped in abusive employment in Oman, their plight hidden behind closed doors, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today. Omani authorities should take immediate steps to reform the restrictive immigration system that binds migrant workers to their employers, provide domestic workers with labor law protections equal to those enjoyed by other workers, and investigate all situations of possible trafficking, forced labor, and slavery.

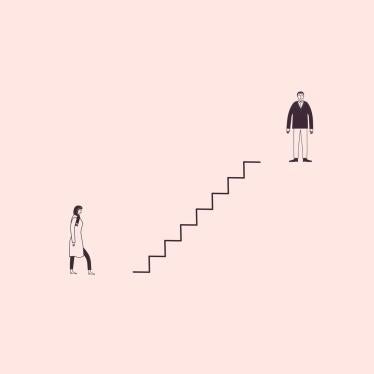

The 68-page report, “‘I Was Sold’: Abuse and Exploitation of Migrant Domestic Workers in Oman,” documents how Oman’s kafala (sponsorship) immigrant labor system and lack of labor law protections leaves migrant domestic workers exposed to abuse and exploitation by employers, whose consent they need to change jobs. Those who flee abuse – including beatings, sexual abuse, unpaid wages, and excessive working hours – have little avenue for redress and can face legal penalties for “absconding.” Families rely on migrant domestic workers to care for their children, cook their meals, and clean their homes. Yet many migrant domestic workers, who rely on their salaries to support their own families and children at home, face cruel and exploitative conditions.

“Migrant domestic workers in Oman are bound to their employers and left to their mercy,” said Rothna Begum, Middle East women’s rights researcher at Human Rights Watch. “Employers can force domestic workers to work without rest, pay, or food, knowing they can be punished if they escape, while the employers rarely face penalties for abuse.”

At least 130,000 female migrant domestic workers, and possibly many more, work in the sultanate. Most are from the Philippines, Indonesia, India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, and Ethiopia.

Human Rights Watch interviewed 59 migrant domestic workers in Oman. In some cases, workers described abuses that amounted to forced labor or trafficking – often across Oman’s porous border with the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Employers typically pay fees to recruitment agencies to secure domestic workers’ services, and several workers said that their employers told them they had “bought” them. Some employers demand that workers reimburse them for recruitment fees for their “release.”

“Asma K.,” from Bangladesh, said she went to the UAE to work there, but that her recruitment agent “sold” her to a man who confiscated her passport and took her to Oman. He forced her to work 21 hours a day for a family of 15 with no rest or day off; deprived her of food; verbally abused and sexually harassed her; and paid her nothing.

“I would start working at 4:30 a.m. and finish at 1 a.m.,” she said. “For the entire day they wouldn’t let me sit. When I said I want to leave, he said, ‘I bought you for 1,560 rials (US$4,052) from Dubai. Give it back to me and then you can go.’”

Most of the workers said their employers confiscated their passports. Many said their employers did not pay them their full salaries, forced them to work excessively long hours without breaks or days off, or denied them adequate food and living conditions. Some said their employers physically abused them; a few described sexual abuse.

The situation is so dire that some countries, such as Indonesia, have banned their nationals from migrating to Oman and other countries with comparable track records. The bans, however, are ineffective, and can put women at heightened risk of trafficking or forced labor as they and recruiters try to circumvent the restrictions. While some countries have increased protections for their nationals who work abroad, others do not fully protect workers against deceptive recruitment practices or provide adequate assistance to abused nationals abroad.

Oman’s restrictive kafala system, also used in neighboring Gulf countries, ties migrant domestic workers’ visas to their employers. They cannot work for a new employer without the current employer’s permission, even if they complete their contract or their employer is abusive. In 2011, Oman told members of the United Nations Human Rights Council that it was “researching an alternative to the [visa] sponsorship system,” but Human Rights Watch is not aware of any concrete proposals made since.

Oman’s labor law explicitly excludes domestic workers, and regulations issued in 2004 on domestic workers provide only basic protection. In April 2016, the Times of Oman quoted a Ministry of Manpower official stating that Oman is considering including domestic workers in its labor law. The Omani government did not respond to Human Rights Watch requests for information on law reforms or other measures to protect domestic workers’ rights.

Domestic workers who said they escaped abusive situations have few options. Some said they sought help from recruitment agents, but that the agents confined them to their offices, beat them, and then forced them to work for new families. Some domestic workers who turned to the police for help said officers dismissed their claims out of hand, and returned them to employers or recruitment agencies. In several cases, workers said that employers beat them after the police returned them.

Domestic workers who leave their employer’s homes also risk their employers reporting them as “absconded,” an administrative offense that can result in deportation and a ban on future employment, or even a criminal complaint against them.

Several Omani lawyers and country-of-origin officials said they have no confidence in Oman’s labor dispute settlement procedure or courts for redress for domestic workers. Some embassy officials discourage domestic workers from pursuing such avenues because the process is lengthy and likely to fail, and the workers cannot work in the meantime. Many workers return home unpaid and without justice.

On June 30, the United States government downgraded Oman’s rating to “Tier 2 Watch List” in its annual Trafficking in Persons report. The Omani government “did not demonstrate evidence of overall increasing efforts to address human trafficking during the previous reporting period,” the report said. In particular, there was a decrease in prosecutions for trafficking, with only five sex trafficking prosecutions in 2015, none on forced labor, and no convictions.

Oman should reform its labor law to provide equal protections to domestic workers, and revise the kafala system to fully and effectively protect migrant domestic workers in line with international standards. It should ratify the International Labour Organization (ILO) Domestic Workers Convention, and bring its laws into compliance with its provisions. It should also cooperate with countries of origin to prevent abuse and exploitation of domestic workers, thoroughly investigate abuses, and prosecute those responsible.

“Omani police and other officials should be protecting domestic workers and prosecuting their abusers, not punishing the workers for escaping,” Begum said. “Oman needs to revise its laws and kafala system so that domestic workers will have the protections they need.”

Selected accounts from the report:

“Mamata B.,” a Bangladeshi domestic worker, said that in April 2015, she told the police that her employer had beat her and refused to pay her for two months. Although she begged not to be sent back, the police called her employer, who took her back and beat her “mercilessly,” then locked her in a room for eight days with only dates and water as sustenance. Mamata fled again, but did not return to the police.

“Aditya F.,” a 30-year-old Indonesian domestic worker from West Java, fled her employer following physical and verbal abuse, and her employer reported her as “absconding.” The police caught Aditya and returned her to the employer who then beat her and broke her teeth.