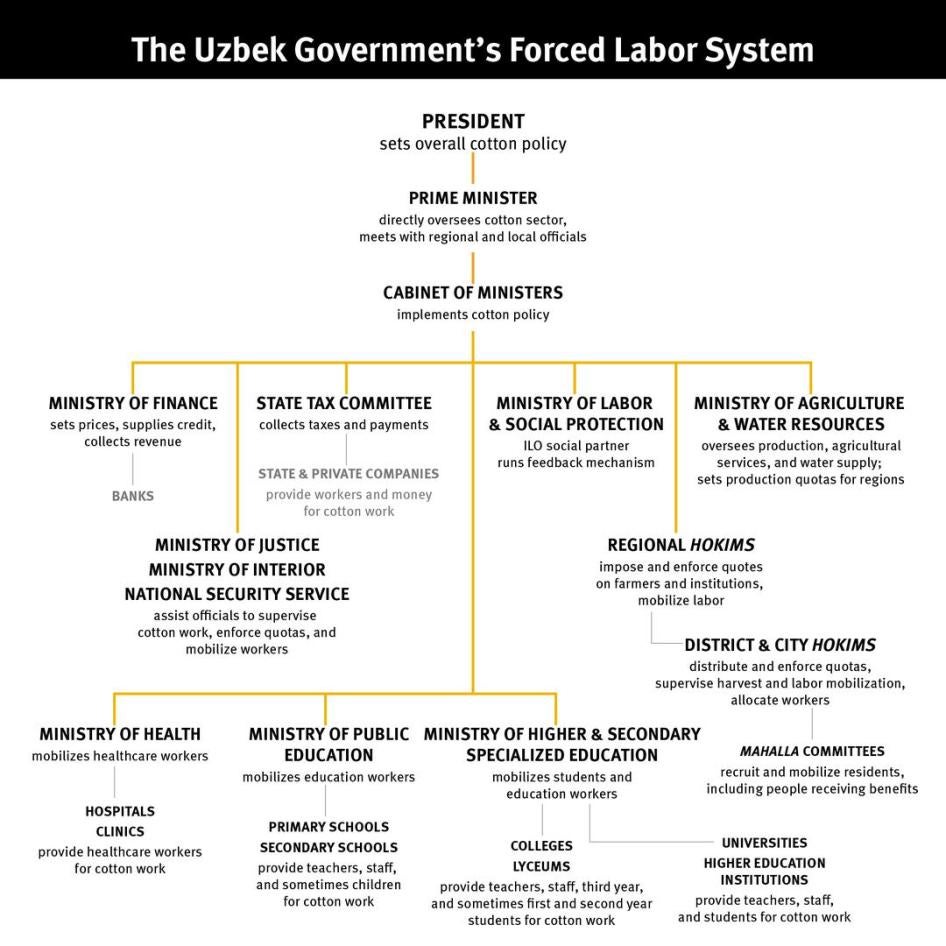

Cotton is essential to Uzbekistan’s economy. Year after year, the government coerces enormous numbers of people to work in its many cotton fields. Despite these abuses, the World Bank invested about half a billion dollars in projects benefiting the cotton sector in 2015 and 2016.

Elena is the only monitor who still openly investigates and documents labor abuses during Uzbekistan’s cotton harvest for UGF. Other monitors operate undercover because of the risk. Elena and the others have faced surveillance, threats, harassment and the frequent confiscation of their notes, phones and flash drives.

For more than seven years, UGF monitors and other activists have gathered a trove of evidence illustrating coercion and arduous working conditions in Uzbekistan’s agriculture sector – including abuses linked to World-Bank-funded projects. In fact, they have gathered far more evidence than the International Labour Organization (ILO), which has been working with the Uzbek government and government-affiliated unions to monitor labor practices during the cotton harvest on behalf of the World Bank.

Elena and other monitors have seen how cotton pickers are often housed for weeks in shelters that are crowded and unsanitary. Sometimes they go without enough food, sleeping on concrete floors, working 10-hour days. Many are threatened with dismissal from their jobs should they defy orders.

Elena has experienced harassment and violence in her attempts to document these conditions. During a 2015 fact-finding trip to Khazarasp district in Khorezm with a local journalist, she visited a school building where high school students, who were being forced to work in the fields, were fed scant amounts of black bread and boiled water.

As she recalls: “We arrived to the cotton field camps in the morning as they were waking up. As we arrived, the police and security services came. They grabbed us with all their strength and threw us into cars. In the Khazarasp police station they took our flashdrives, cameras, strip searched us, they even brought a gynecologist in to do a body cavity search, right in the police station. We are already used to this, they search us like this, to prevent us from bringing our flash drives home so we can’t share information with the international community.”

The Uzbek government’s widespread use of forced labor not only violates international and Uzbek law, it also contravenes the country’s loan agreements with the World Bank. Yet, instead of suspending its agriculture loans to the government, the World Bank has increased its investments, claiming “a genuine commitment” by Uzbekistan’s government “to abide by its national laws and international commitments.”

The Uzbek Labor Ministry has been displaying posters and billboards saying that “everyone is eligible to refuse to pick cotton,” and publicized hotlines to report violations. After all, the government’s agreement with the Bank requires it to keep forced labor out of World Bank project areas.

But the hotlines are run by the very same government that mobilizes people to work under threat and by government-affiliated trade unions, so not many people dare to report violations. “People don’t trust the hotlines,” Elena says. “They are afraid of reprisals, afraid of losing their jobs and of being branded an enemy of the people.”Elena knows all too well that in Uzbekistan, people’s fear of their government is not unfounded.

She has worked as an activist for 18 years, determined to expose Uzbekistan’s abusive state-run program of forced labor. To do so, she says, she has to “operate like a guerrilla”— sneaking out unseen, hiding in the dark early in the morning, before people arrive at their place of work.

Repeatedly, state authorities have committed her to psychiatric hospitals, and a court even declared her insane.

In the hospitals, she says, she was subjected to forcible treatments that caused her hands to shake and made her sick. Last year, hospital authorities did not even try to pretend her stay was necessary for medical reasons, citing “official orders” when refusing to discharge her. International pressure eventually led to her release. Since then, she says, she has been under constant surveillance by Uzbekistan’s security service, the country's most powerful and feared institution.

“Our government very clearly does not want any information about forced labor to reach the international community,” she says.

A canvas bag swung over her shoulder, Elena walks the fields, handing out leaflets about the hotline and the right to refuse to take part in the harvest. “Did you know that doctors and nurses do not have to pick cotton,” she asks the surgeons, oncologists, and neuropathologists in the fields. “There are chemicals here – this is not healthy,” she tells pregnant women and high school students as young as 16.

But people tell Elena time and again, “If we refuse to pick, we will lose our jobs and our bread to eat.”

The ILO has failed to expose these abuses through its own monitoring work, as it is obliged to collaborate with the government and Uzbekistan’s official labor unions, which are under government control. Workers are coached and intimidated into lying to the ILO about their real jobs, or to claim to be picking cotton voluntarily to earn extra money. Elena and her colleagues have seized every opportunity to make the real stories known, but neither the ILO nor the World Bank have given sufficient weight to this information. The World Bank continues to fund projects tied to forced labor.

“They will not give up this system of mass-scale forced labor voluntarily,” Elena says. “Taking people from their jobs and sending them to the fields [to work] for free is just too beneficial for them.”

“We human rights defenders have a responsibility to change this, for our people’s sake.”