Summary

Cotton is mandatory for everyone. The government gave the orders [to pick] and you will not go against those orders…. If I refuse, they will fire me…. We would lose the bread we eat.

−Uzbek schoolteacher, October 2015, Turtkul, Karakalpakstan

For several weeks in the fall of 2015, government officials forced Firuza, a 47-year-old grandmother, to harvest cotton in Turtkul, a district in Uzbekistan’s most western region, the autonomous Republic of Karakalpakstan. The local neighborhood council, the mahalla committee, had threatened to withhold child welfare benefits for her grandson if she did not go to the fields to harvest cotton. These same officials forced another woman, Gulnora, to harvest cotton for the same length of time. Although Gulnora worked, the government refused to pay her child welfare benefits, promising to consider reinstating them if she worked in the fields the next spring. The Uzbek government forces enormous numbers of people to harvest cotton every year through this kind of coercion.

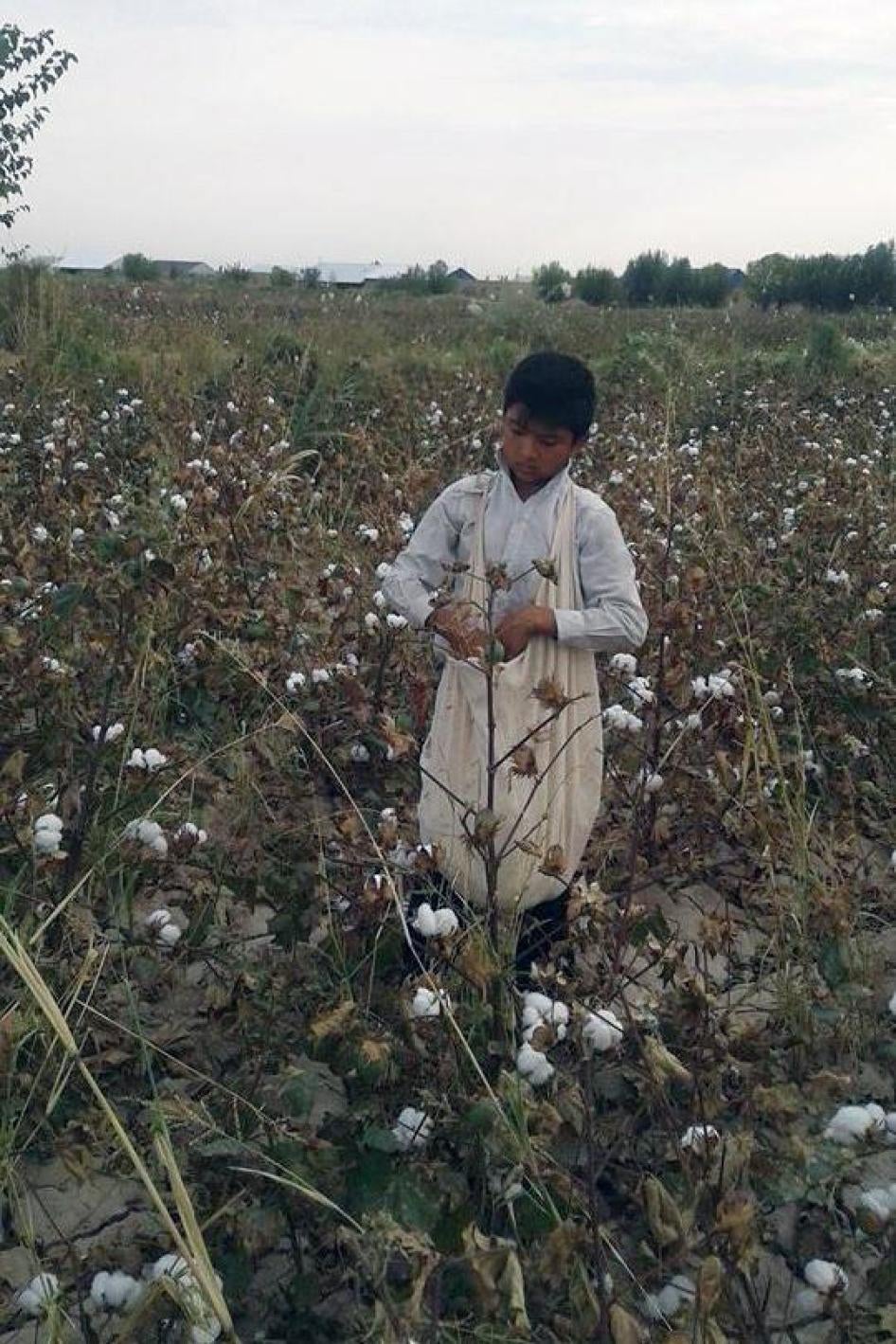

The government’s abusive practices are not confined to adults. During the 2016 harvest the government forced young children to work in the cotton fields. In Ellikkala, a district neighboring Turtkul, officials from at least two schools ordered 13 and 14-year-old children to pick cotton after school. The Uzbek-German Forum for Human Rights saw children working in one of the cotton fields, and a teacher ordering the children to hide. The World Bank has funded an irrigation project in these districts on the condition that the Uzbek government comply with laws prohibiting forced and child labor. Despite this agreement, the Uzbek government has continued to force people, including children, to work within the project area.

Withholding child benefits and other welfare payments is just one of the penalties the government has used to force people to work. The government has threatened to fire people, especially public sector employees who are among the lowest paid in the country. Students who refused to work faced the threat of expulsion, academic penalties, and other consequences. People living in poverty are particularly susceptible to forced labor, as they are unable to risk losing their jobs or welfare benefits by refusing to work and cannot afford to pay people to work in their place.

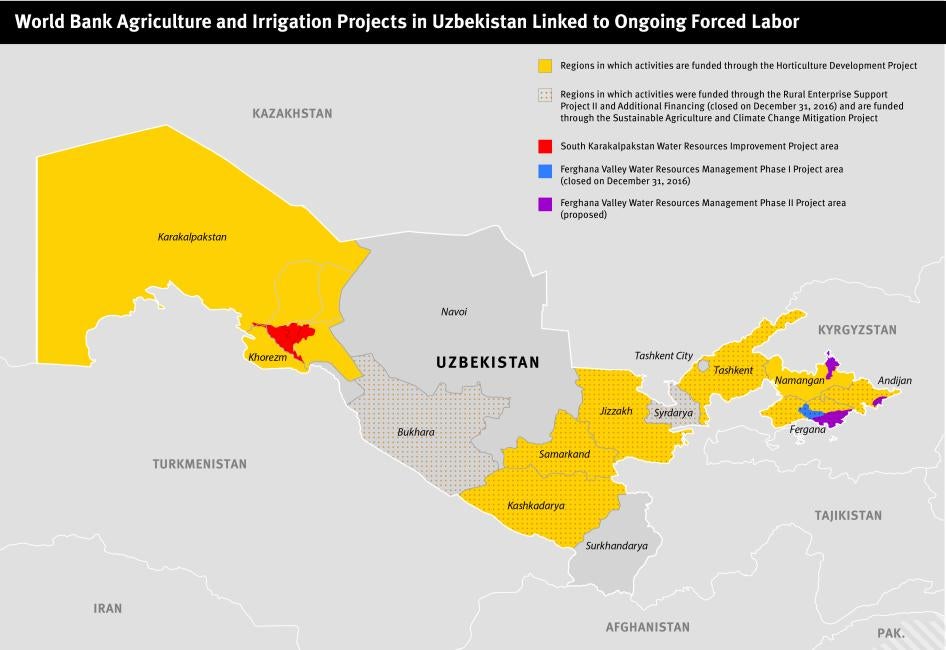

Based on interviews with victims of forced labor in September to November 2015, April to June and September to November 2016, and early 2017, leaked government documents, and statements by government officials, this report details how the Uzbek government forced students, teachers, medical workers, other government employees, and private-sector employees to harvest cotton in 2015 and 2016, as well as prepare the cotton fields in the spring of 2016. The report documents forced adult and child labor in one World Bank project area and demonstrates that it is highly likely that the Bank’s other agriculture projects in Uzbekistan are linked to ongoing forced labor in light of the systemic nature of the abuses. The report also finds that there is a significant risk of child labor in other Bank agricultural projects in the country.

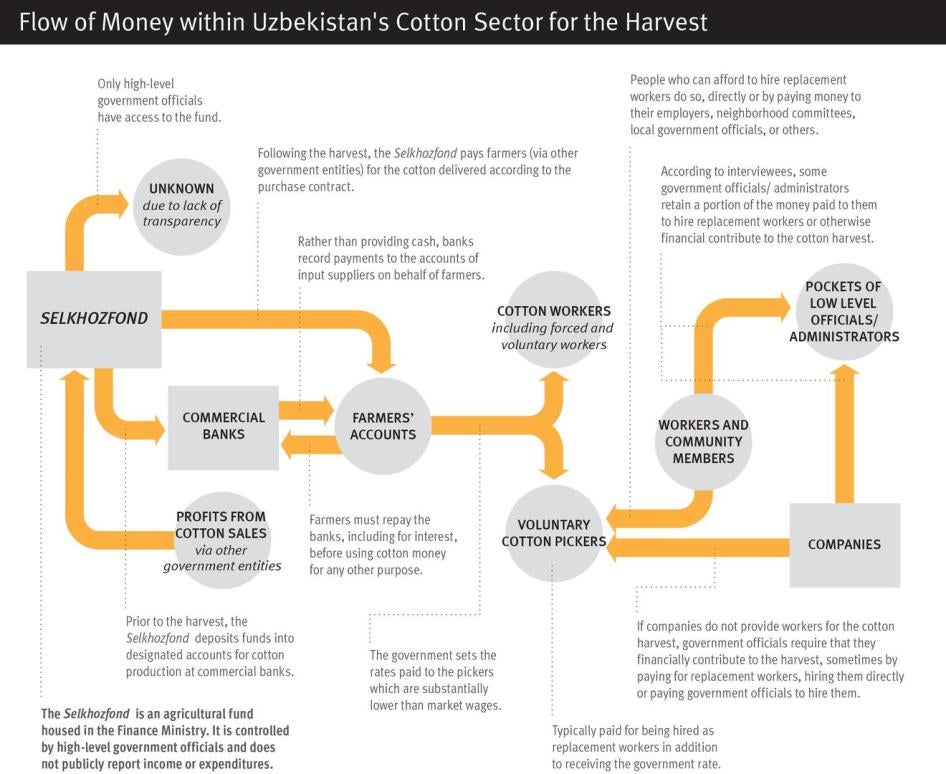

Uzbekistan is the fifth largest cotton producer in the world. It exports about 60 percent of its raw cotton to China, Bangladesh, Turkey, and Iran. Uzbekistan’s cotton industry generates over US$1 billion in revenue, or about a quarter of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP), from one million tons of cotton fiber annually. These funds go into an opaque extra-budgetary account, the Selkhozfond, housed in the Ministry of Finance, that escapes public scrutiny and is controlled by high-level officials.

Campaigns by a number of groups against forced and child labor in Uzbekistan’s cotton sector have resulted in boycotts of Uzbek cotton. For example, 274 c0mpanies have pledged not to knowingly source cotton from Uzbekistan because of forced and child labor in the sector. Despite this, the World Bank remains active in the country’s agriculture sector providing a total of $518.75 million in loans to the government for projects in this sector in 2015 and 2016.

In Turtkul, Beruni, and Ellikkala districts in Karakalpakstan, the World Bank has worked with the Uzbek government since April 2015 under a $337.43 million irrigation project. Cotton is grown on more than 50 percent of the arable land within this project area. The World Bank secured a commitment from the Uzbek government to comply with national and international forced and child labor laws in the project area and agreed that the loan could be suspended if there was credible evidence of violations.

Since the World Bank approved this project in 2014, the Uzbek government has continued to force people, sometimes children, to work in the cotton sector in Turtkul, Beruni, and Ellikkala, including within the Bank’s project area. Independent groups, including the Uzbek-German Forum for Human Rights, submitted evidence of forced and child labor to the World Bank during and following the 2015 harvest, which runs from early September until early to mid-November annually. Instead of suspending its loan to the government, in line with the 2014 agreement between the two parties, the World Bank increased its investments in Uzbekistan’s agriculture industry through its private sector lending arm, the International Finance Corporation (IFC).

Shortly after the 2015 cotton harvest, the IFC invested in a government joint venture with a subsidiary of Indonesia’s Indorama Corporation, Indorama Kokand Textile, a leading cotton yarn producer in Uzbekistan. In December 2015 the IFC agreed to loan Indorama $40 million to expand its textile plant, which uses solely Uzbek cotton. Given the scale of forced labor in Uzbekistan and its systemic nature, it is highly unlikely that a company could source any significant quantity of cotton from Uzbekistan at present that has not been harvested, at least in part, by forced laborers. There is also a significant risk of child labor.

According to the IFC, Indorama tracks its purchases from sites where cotton is processed to mitigate the risk of child and forced labor. Together with the IFC, Indorama has developed a system for rating the risk level of districts in which gins are located. But this system is deeply inadequate. The IFC’s Environmental and Social Performance Standards, which are designed to prevent the IFC from investing in projects that harm people or the environment, require clients to identify risks of, monitor for, and remedy forced and child labor in their supply chains. The Performance Standards provide that where remedy is not possible, clients must shift the project’s primary supply chain over time to suppliers that can demonstrate that they do not employ forced and child labor.

The World Bank is also heavily invested in the country’s education sector, where forced and child labor have undermined access to education, and its quality, because teachers, and students, including children, have had to leave school for up to several months to work in cotton fields. Through direct funding and the Global Partnership for Education, a multistakeholder funding platform, the World Bank provides almost $100 million in financing for education projects in Uzbekistan.

The government has greatly reduced the number of children it forces to work since 2013, primarily by ordering government officials down the line of command to mobilize adults rather than children. However, Human Rights Watch and the Uzbek-German Forum documented more cases of state-organized child labor through schools mobilizing children in 2016 than in the previous year. For example, in addition to child labor in Karakalpakstan described above, in 2016 children and teachers in two districts in Kashkadarya and a school employee in rural Fergana told Human Rights Watch and the Uzbek-German Forum that local officials required schools to mobilize children as young as 10 or 11 years old to pick cotton and suspended classes during this period. They noted that in several districts this was worse than 2015, when children received some classes prior to being sent to pick cotton.

The World Bank’s Unsuccessful “Mitigation” of Forced Labor

The World Bank has a long history of investing in Uzbekistan’s agriculture sector, but a poor record of addressing forced and child labor in the projects it funds. The Bank only acknowledged this problem after forced laborers filed a complaint with the World Bank’s independent accountability mechanism, the Inspection Panel, in 2013. Thatcomplaint alleged that a Bank agriculture project was contributing to the perpetuation of forced and child labor in Uzbekistan.

In response, the World Bank introduced several measures to mitigate the risk of these labor abuses being linked to existing and proposed Bank projects. It required the government to comply with national and international laws on forced and child labor. It also committed to establish third party monitoring of labor practices in the Bank’s project areas and to implement a grievance mechanism through which victims of forced labor would be able to complain and receive some redress. These mitigation measures do not adequately address government-organized, systematic forced labor in Uzbekistan’s cotton sector. Ultimately, the Bank found that it could not implement some of its commitments, so it settled for weaker measures.

For example, the World Bank contracted the International Labour Organization (ILO), a tripartite UN agency made up of governments, employer organizations, and worker representatives, to monitor forced and child labor in partnership with the Uzbek government, instead of independently monitoring the government’s practices. The ILO has an important role to play in promoting fundamental labor rights in Uzbekistan. However, it allowed the involvement of government and government-aligned organizations in the monitoring effort. The lack of independence of labor unions in Uzbekistan further compromises the ILO’s work in Uzbekistan. Under this structure, in reality, the government that mandates forced labor and utilizes child labor is allowed to monitor itself. While the World Bank has acknowledged these limitations privately, publicly it continues to refer to the ILO as undertaking “independent monitoring.”

The credibility of the ILO’s findings has been further undermined by evidence that the government coached ILO interviewees. The ILO reported that “Many interviewees appeared to have been briefed in advance.” Numerous people told Human Rights Watch and the Uzbek-German Forum that government officials or their supervisors told people to say they were local and unemployed, picking cotton voluntarily, or that they worked as cleaners or guards in their schools and hospitals instead of teachers and medical staff. If the monitors already knew that they were teachers, then they were to say that they voluntarily picked cotton after they had finished teaching classes.

There is no proper grievance mechanism either. Instead of an independent mechanism, the Ministry of Labor and a government-controlled trade union federation are responsible for obtaining feedback from workers, undermining its credibility among workers. This system has resulted in reprisals against complainants and a general dismissal of their concerns, both of which have compounded the lack of trust in the mechanism.

The World Bank has not recognized that Uzbekistan has breached its loan agreements with the Bank in continuing to force adults and some children to work in its project area, despite receiving evidence from independent groups including Human Rights Watch and the Uzbek-German Forum of these abuses. The ILO similarly reported to the World Bank that it observed indicators of forced labor in the country in 2015 and that there were ongoing risks of forced labor in 2016 including in Bank project areas.

Instead of suspending key loans to Uzbekistan, the World Bank has lauded the government for its efforts, saying, “The government is taking actions, albeit in a very incremental and cautious manner, that reflect a genuine commitment to abide by its national laws and international commitments.” Bank staff have pointed to legal changes, the government’s cooperation with the ILO, increased training on forced and child labor, the promise of mechanization, the government’s commitment to reduce the land on which it requires farmers to grow cotton, and reports that at least one government official was dismissed for violating forced and/or child labor laws in November 2016. The Bank also noted that, according to the ILO, the number of people that refused to work in the cotton harvest doubled from 2014 to 2015. While these are notable developments, none of these steps directly addressed the fact that forced and child labor continue to be linked to Bank-supported projects in violation of the Bank’s agreements with the Uzbek government.

Threats and Reprisals Against Human Rights Defenders

The Uzbek-German Forum’s monitors, as well as other people conducting human rights and labor rights monitoring work, faced constant risk of harassment and persecution in 2015 and 2016. In several regions, local authorities, including police, prosecutors, and representatives of mahalla committees, called in monitors for questioning, accused them of being involved in illegal or “bad” activities, threatened them with charges, loss of jobs, or other penalties, and in some cases confiscated their research materials. Local police and central government officials have also arbitrarily prevented monitors from traveling in connection with their human rights work.

In 2015 this harassment reached unprecedented levels as the government used arbitrary arrest, threats, degrading ill-treatment, and other repressive means to undermine the ability of monitors to conduct research and provide information to the ILO and other international institutions. One monitor, Dmitry Tikhonov, had to flee the country and another, Uktam Pardaev, was imprisoned for two months and released on a suspended sentence. Police told Pardaev that he is subject to travel restrictions and a curfew, although these are not stipulated in the sentence, and have surveilled and intimidated his relatives and friends. He risks going to prison if found to violate conditions of release, which he believes could be used to retaliate against him for speaking out about human rights abuses.

In 2016 only one Uzbek-German Forum monitor, Elena Urlaeva, continued to work openly, and she was subjected to surveillance, harassment, arbitrary detentions and other abuses. On March 1, 2017, police again detained Urlaeva. After reportedly insulting and assaulting her, police sent Urlaeva to a psychiatric hospital for forced treatment. The hospital released her on March 23. Urlaeva said she believes authorities detained her to prevent her from meeting with representatives of the World Bank and the ILO. In Karakalpakstan, where the World Bank irrigation project is being implemented, authorities questioned and intimidated another Uzbek-German Forum monitor, who did not work openly, and amember of his family, suspecting him of monitoring. Security forces also arrested an independent monitor in this area and briefly detained him.

The United Nations Human Rights Committee has raised concerns about forced labor and the treatment of individuals attempting to monitor labor practices in Uzbekistan. Human Rights Watch and others have repeatedly recommended that the Bank include a covenant in loan and financing agreements explicitly allowing independent civil society and journalists unfettered access to monitor forced and child labor, along with other human rights abuses within the Bank’s project areas and to prohibit reprisals against monitors, those that speak to them, or people that lodge complaints. The World Bank refused.

In 2015 and 2016 the World Bank said that it spoke with the Uzbek government about alleged reprisals. Nonetheless, reprisals continued and the Bank has not escalated its response.

The Way Forward for the Government of Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan’s former authoritarian president, Islam Karimov, whose death was reported on September 2, 2016, left a legacy of repression following his 26-year rule. The country’s new president, Shavkat Mirziyoyev, promised increased accountability and acknowledged the lack of reform in key aspects of Uzbekistan’s society, including the economy and the criminal justice system. Despite these statements and the release of several political prisoners, Uzbekistan’s rights record remains atrocious. This leadership change provides a good moment for concerned governments and international financial institutions to press for comprehensive reforms to dismantle Uzbekistan’s forced labor system and provide accountability for past abuses.

Reform of the cotton sector, with its rampant corruption and abusive labor practices, would be a significant step in realizing Mirziyoyev’s promise of accountability. However, Mirziyoyev’s previous positions raise concerns about his credibility. As prime minister from 2003 to 2016 he oversaw the cotton production system, and as the previous governor of Jizzakh and Samarkand, he was in charge of two cotton-producing regions. The 2016 harvest, when Mirziyoyev was acting president and retained control over cotton production, continued to be defined by mass involuntary mobilization of workers under threat of penalty.

As this report outlines, the government can implement immediate reforms to show a real commitment to ending forced labor, including by significantly curtailing forced labor and eliminating child labor in the cotton sector, as well as implementing broader reforms in the agricultural sector to address the root causes of forced labor. Basic steps would include enforcing laws that prohibit the use of forced and child labor, instructing government officials to stop coercing people to work, and allowing independent journalists and human rights defenders to freely monitor the cotton sector without fear of reprisals.

The Way Forward for the World Bank, International Finance Corporation

The World Bank should suspend disbursements in all agriculture and irrigation financing in Uzbekistan until the government fulfills its commitments under World Bank agreements not to utilize forced or child labor in areas where there are Bank-supported projects. The IFC should similarly suspend disbursements to investments in Uzbekistan’s cotton industry until its borrowers can show that they do not source cotton from fields tainted byforced or child labor.

In addition, the World Bank and the IFC should take all necessary measures to prevent reprisals against monitors who document and report on labor conditions or other human rights issues linked, directly or indirectly, to their projects in Uzbekistan. The institutions should closely monitor for reprisals and, should they occur, respond promptly, publicly, and vigorously, including by pressing the government to investigate and hold to account anyone who uses force or threatens persons reporting human rights concerns. They should also independently investigate alleged violations and work to remedy harms suffered from reprisals.

In addition, the World Bank and IFC should publicly and regularly report on reprisals linked in any way to their investments, as well as the actions they took to respond. The Bank should amend its project agreements in Uzbekistan to require the government to allow independent journalists, human rights defenders, and other individuals and organizations access to monitor and report on forced and child labor, along with other human rights abuses in all World Bank Group project areas. The agreements should also require the government to ensure that no one faces reprisals for monitoring human rights violations in project areas, bringing complaints, or engaging with monitors.

Recommendations

To the World Bank

- Suspend all disbursements and future financing to the Uzbek government for agriculture and irrigation projects until the government is not using forced or child labor in World Bank project areas.

- Prior to disbursing any more funds for the relevant agriculture and irrigation projects, require the government of Uzbekistan to:

- Instruct all government officials and citizens that act on behalf of the government not to coerce people and institutions to mobilize forced laborers;

- Allow independent monitoring of the cotton sector, including by journalists, human rights defenders, and other individuals without fear of reprisals; and

- Initiate a time-bound plan to reform root causes of forced and child labor in the agriculture sector, including ensuring national budgets reviewed by the Oliy Majlis include expenditures and income in the agriculture sector.

- Amend existing irrigation, agriculture, and education project agreements to allow independent parties to monitor World Bank project areas and to prohibit reprisals against monitors, people who bring complaints or use the feedback mechanism, and people who engage with monitors. Insist publicly and privately that a condition of financing is that independent human rights defenders, journalists, and other monitors be able to work without impediments or fear of reprisals.

- Engage a third party monitor fully independent from the government to robustly research and report on compliance with core labor conventions in agriculture, irrigation, and education project areas. Such monitoring should:

- Include independent civil society organizations;

- Cover forced and child labor in the cotton sector during the spring field preparation season, as well as in the lead-up to and during the harvest; and

- Cover forced and child labor in the horticulture sector.

- Establish a confidential and accessible grievance mechanism and provide effective remedies, including legal and financial, to any person who is subjected to forced or child labor in the project areas or otherwise linked to the projects.

To the International Finance Corporation (IFC)

- Suspend disbursements to all cotton sector investments in Uzbekistan until borrowers can demonstrate that they do not source from fields where forced or child labor is used.

- Do not fund companies that have produced products using forced or child labor in Uzbekistan until they have changed their practices and remedied past abuses.

- Conduct and publish an independent audit of banks in Uzbekistan receiving World Bank Group funds to determine whether they have:

- forced employees to work in the cotton fields or hire replacement workers; or

- supported or contributed to forced labor, child labor, or other abuses linked to the cotton sector through their investments or conduct.

- Based on this audit, require the banks to implement the necessary reforms.

To the World Bank Group Board of Executive Directors

- Direct World Bank and IFC management to implement the above recommendations and report to the Board quarterly on their progress.

- For any project in Uzbekistan, ensure that an assessment of forced and child labor risk is presented to the Board. Do not approve projects in areas in which forced or child labor are systemic to the very industry the Bank is investing in or investments in companies that have and continue to use products made with forced or child labor.

To the Government of Uzbekistan

- Enforce national laws that prohibit the use of forced and child labor in alignment with ratified ILO conventions.

- Make public, high-level policy statements condemning forced labor, specifically including forced labor in the cotton sector, and making clear that all work should be voluntary and fairly compensated.

- Instruct government officials at all levels and citizens that act on behalf of the government not to use coercion to mobilize anyone to work.

- Allow independent journalists, human rights defenders, and other individuals and organizations to document and report concerns about the use of forced or child labor without fear of reprisals.

- Take immediate steps to provide, in practice, effective protection of independent journalists, human rights defenders, and other activists against any actions that may constitute harassment, persecution, or undue interference in the exercise of their professional activities or of their right to freedom of opinion, expression, and association. Ensure that such acts are thoroughly and independently investigated, prosecuted and sanctioned, and that victims are provided with effective remedies.

- Fully implement ILO Convention No. 87 on Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organise, which the government ratified in October 2016.

- Initiate a time-bound plan to reform root causes of forced labor in the agriculture sector, including:

- Cease punitive measures against farmers for debts and not meeting state-mandated production quotas for cotton and other agricultural products;

- Ensure the state-established procurement prices for cotton and other agricultural products reflect the costs of production, including the cost of voluntary labor at market rates, and, over time abolish the state monopsony on cotton purchasing; and

- Increase financial transparency in the agriculture sector, including by ensuring national budgets reviewed by the Oliy Majlis include expenditures and income in the agriculture sector and ensuring taxes paid in the sector go to the national budget.

To the International Labour Organization (ILO)

- Insist publicly and at the highest levels that independent monitors be able to work unimpeded and safely, highlighting that this is a key indicator of the government’s good faith and a requirement for ILO assistance. Raise concerns about attacks on independent monitors in all ILO reports on Uzbekistan.

- Cease providing a monitoring role for the World Bank, instead focusing on its core mission in Uzbekistan: to promote fundamental labor rights and to devise programs promoting decent work for all.

- Include the International Union of Food, Agricultural, Hotel, Restaurant, Catering, Tobacco and Allied Workers' Associations (IUF), which represents agriculture workers, in discussions planning and developing methodologies for the ILO’s work in Uzbekistan.

To Indorama and Other Textile Companies Operating in Uzbekistan

- Adopt, publish, and implement a clear policy commitment to respect human rights, embedded in all relevant business functions.

- Identify and assess actual and potential adverse human rights impacts in the company’s supply chain and prevent and mitigate adverse impacts, particularly forced and child labor as well as other labor abuses. If the company cannot address the significant risk of forced and child labor in its supply chain in Uzbekistan, cease sourcing cotton from Uzbekistan.

- To avoid perpetuating forced and child labor, ensure that pricing and sourcing contracts adequately reflect the cost to suppliers of labor.

- Establish regular and rigorous internal and third party monitoring in Indorama’s supply chain, including through unannounced inspections. Engage qualified, experienced, and independent monitors trained in labor rights. Include private, confidential interviews with workers, as well as farmers, as components of inspections. Make the results of internal and third party monitoring public.

- Regularly publicly disclose all farms from which cotton is sourced, indicate the level of production, and disclose when the unit was most recently inspected by independent monitors.

- Verify and publicly report whether adverse human rights impacts are addressed.

- Establish a meaningful and effective complaint mechanism whereby people can submit complaints about labor abuses or other human rights violations without fear of reprisal. Ensure that adversely affected people can secure remedy for being subjected to labor abuses or other abuses and receive appropriate protection from reprisals, including legal representation to defend themselves against vexatious lawsuits or criminal complaints filed by the government.

To Commercial Banks Operating in Uzbekistan

- Adopt and implement a clear policy commitment to respect human rights, embedded in all relevant business functions.

- Identify and assess actual and potential adverse human rights impacts in all investments and prevent and mitigate adverse impacts, particularly coercion of farmers, forced and child labor, and other labor abuses. Only provide funding to activities in which the bank can address the significant risk of forced labor or other human rights abuses.

- Do not require employees to harvest cotton or pay for replacement workers.

- Establish regular and rigorous internal and third party monitoring of investments in which there is a risk of forced labor, child labor, or other abuses, including through unannounced inspections. Engage qualified, experienced, and independent monitors trained in labor rights. Include private, confidential interviews with workers, as well as farmers, as components of inspections. Make the results of internal and third party monitoring public.

- Establish a meaningful and effective complaint mechanism whereby people can submit complaints about any concerns about labor or other human rights abuses in the bank’s investments without fear of reprisal. Ensure that adversely affected people can secure remedy for being subjected to labor or other abuses and appropriate protection from retaliation.

Methodology

This report is based on research carried out by the Uzbek-German Forum for Human Rights (Uzbek-German Forum) in Uzbekistan during the 2015 fall cotton harvest, spring cotton planting and weeding season in 2016, and the 2016 fall harvest.

Twenty-two Uzbek-German Forum monitors researched whether there was forced or child labor in Uzbekistan’s cotton fields in the 2015 harvest from September to November, 20 monitors in the 2016 planting and weeding season from April to June, and 18 monitors in the 2016 harvest in the country’s Andijan, Jizzakh, Kashkadarya, Syrdarya, and Tashkent regions, and the Beruni, Ellikkala, Turtkul, districts in the Republic of Karakalpakstan, an autonomous region in Northwestern Uzbekistan, covering 160,000 square kilometers (62,000 square miles). In addition, monitors conducted research in Fergana in 2016, in Bukhara in 2015, and undertook a fact-finding mission to Khorezm in fall 2015. In 2017 Human Rights Watch interviewed seven Uzbeks outside the country, four who worked for the 2016 cotton harvest, one who monitored the harvest, and two who both worked for the harvest and monitored for abuses.

From September to November 2015 the Uzbek-German Forum conducted in-depth interviews in private with 98 people, in May and June 2016 with 63, and from September to December 2016 with 89. Interviewees included schoolteachers, college and university students, farmers, employees of government institutions, including mahalla committees, medical professionals, entrepreneurs, and children. In addition, the Uzbek-German Forum spoke briefly to approximately 400 people during visits to cotton fields, mobilization sites where people gathered to be taken to the fields, and relevant institutions, including schools, colleges, universities, hospitals, clinics, and local government offices in 2015, and approximately 300 people in 2016.

In early to mid-September 2015 and 2016, when the government mobilized the largest number of workers to pick cotton for extended shifts (as opposed to daily shifts close to their homes), the Uzbek-German Forum visited hokimiats (regional and district administrations) and other locations where workers were gathered to be sent to the fields, usually by bus.

In 2015 the Uzbek-German Forum visited five cotton fields in Khorezm, Bukhara, Jizzakh, and Tashkent regions, and six facilities that were being used to house cotton pickers in the Khorezm and Syrdarya regions. In 2016 the Uzbek-German Forum visited 34 cotton fields, including fields in all regions it monitored, and 6 worker housing facilities. The Uzbek-German Forum visited dozens of hospitals and clinics, educational institutions, government establishments, and large markets throughout the 2015 and 2016 cotton harvests.

As a result of government interference in monitoring efforts, several monitors, facing severe reprisals, had to stop their monitoring work. Only one monitor was able to work openly in 2016.

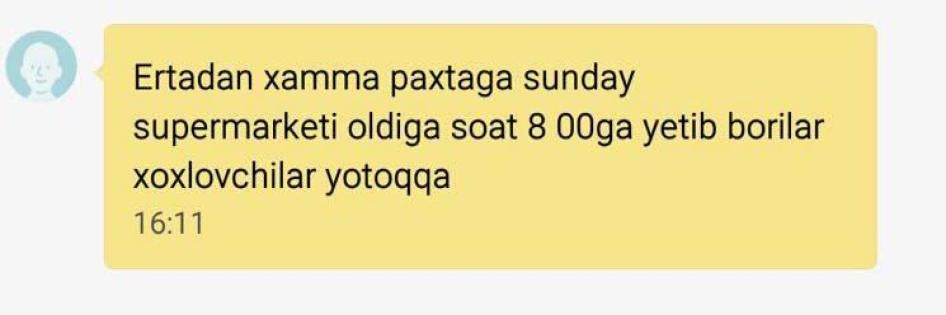

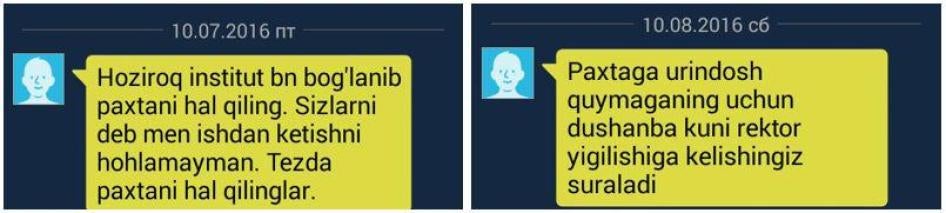

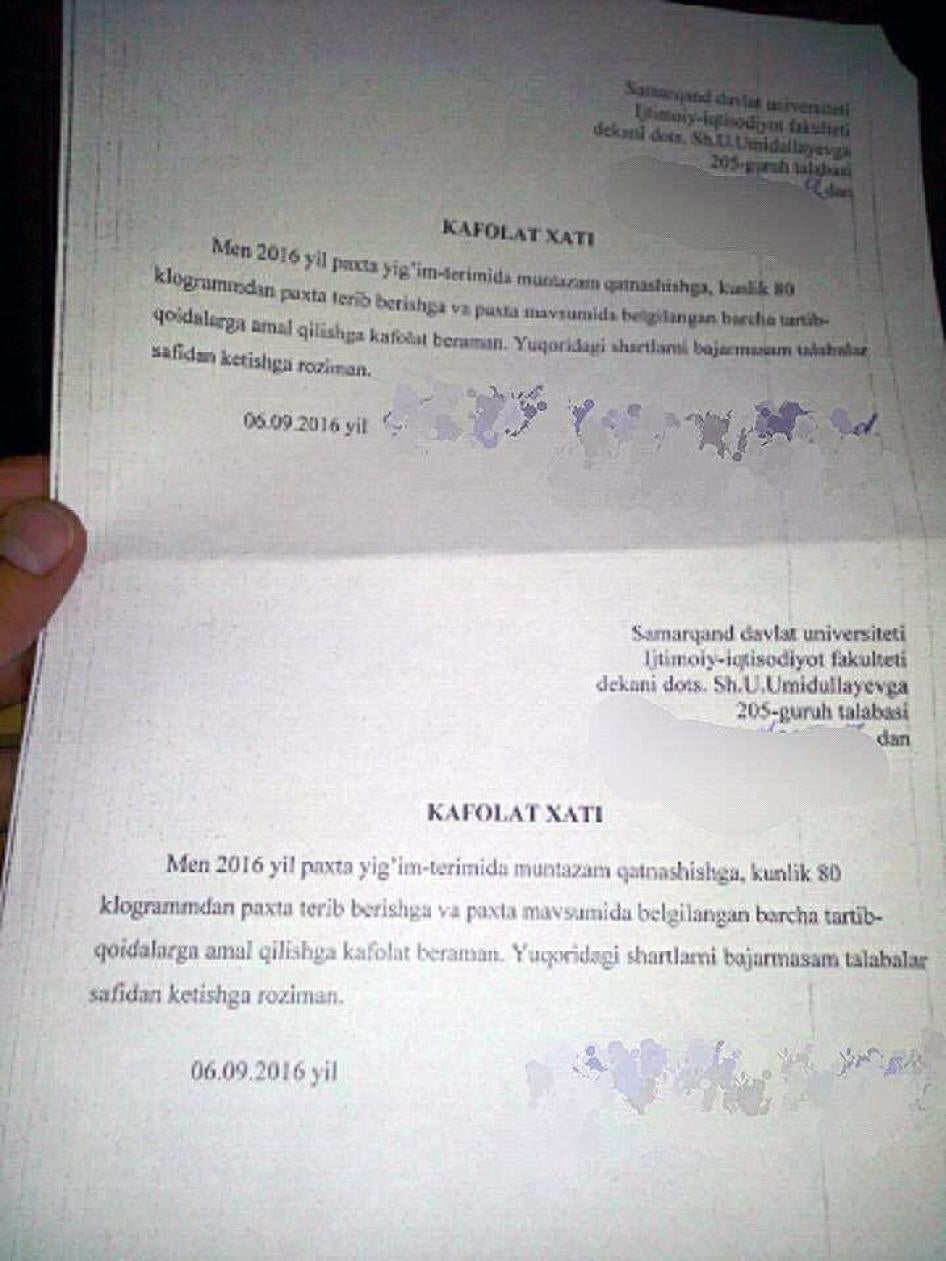

The Uzbek-German Forum also gathered information from documentary sources, including orders signed by directors of enterprises to send workers to the harvest or to weed cotton, decrees by hokims (city mayors and district and regional governors) ordering employees of public institutions to participate in the harvest, ledgers tracking labor mobilization from public institutions, and notes signed by students and others declaring their “voluntary participation in the cotton harvest.” The Uzbek-German Forum also monitored local newspapers and social media posts, and in 2016, posted a request for information about the cotton harvest on the website of Ozodlik, the Uzbek-language service of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. They received more than 50 messages, which were used to corroborate information gathered during interviews.

Interviews conducted by the Uzbek-German Forum were conducted in Uzbek or Russian, without translation. Several of the Uzbek-German Forum’s monitors themselves participated in the cotton harvest, forced by the government in the line of their primary employment. Because of the significant risk of retaliation in Uzbekistan, names have been withheld or replaced by pseudonyms to protect identities throughout this report, and other identifying information has been removed as necessary. In some cases we have removed all identifying information including the region to ensure that those involved are not identifiable.

To explain Uzbekistan’s cotton system, in addition to consulting official sources, Human Rights Watch and the Uzbek-German Forum relied on two key papers that corroborate the Uzbek-German Forum’s field research over the past eight years. The first, “Uzbekistan’s Cotton Sector: Financial Flows and Distribution of Resources,” by Bakhodyr Muradov and Alisher Ilkhamov, is based in part on information provided by a former Uzbek government official writing under the pseudonym Bakhodyr Muradov. This paper provides new information on the cotton financing scheme, flow of resources, and costs of cotton production that has not been published elsewhere. The second is “A Comparative Study of Cotton Production in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan,” by Anastasiya Shtaltovna and Anna-Katharina Hornidge.

Human Rights Watch and the Uzbek-German Forum met with the World Bank and the International Labour Organization (ILO) on numerous occasions over the past several years, often together with other representatives from the Cotton Campaign, a global coalition of human rights, labor, investor, and business organizations dedicated to eradicating forced and child labor in cotton production. Relevant information obtained from these meetings is reflected in this report.

Human Rights Watch and the Uzbek-German Forum wrote to the World Bank, the IFC, the government of Uzbekistan, the ILO, and Indorama on August 15, 2016 and in May 2017, as well as Hamkorbank, and Asaka Bank on August 15, 2016 seeking their response to the findings of this report. All the letters are online at https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/06/06/we-cant-refuse-pick-cotton-uzbekistan-report-letters.

Indorama and Hamkorbank responded to our letters but declined to directly answer our questions. Indorama’s responses are integrated throughout this report. Human Rights Watch and the Uzbek-German Forum met the World Bank and IFC in September 2016; information provided by the two organizations is integrated throughout the report. The government of Uzbekistan, ILO, and Asaka Bank did not respond to our letters.

Glossary of Terms and Abbreviations

|

College |

Equivalent to high school in the United States. Students attend for three years, usually from 16-18 years old. |

|

Cotton gin |

A machine that separates cotton seeds from cotton fibers. The term also refers to the state-controlled cotton association that is responsible for raw cotton procurement and ginning. |

|

Hokim |

Head of city, district, or regional administration, similar to a mayor or governor. The same term is used for all levels of government. |

|

Hokimiat |

City, district, or regional administration. The same term is used at all levels. |

|

IFC |

International Finance Corporation, an arm of the World Bank Group that finances and provides advice for private sector ventures in developing countries. |

|

ILO |

International Labour Organization, a tripartite UN agency made up of governments, employer organizations, and worker representatives. |

|

Khashar |

Uzbek tradition of community service whereby community members engage in “voluntary mutual support,” for example, helping each other with farm work or building a new house. |

|

Mahalla |

Neighborhood or local community, which can refer to the physical location, a community, or a state administrative unit. |

|

Mahalla committee |

A form of local self-government in practice directed by and financially dependent on the district and city hokimiat. |

|

RESP II |

World Bank financed Rural Enterprise Support Project Phase II, which funded the government to provide financing to farmers and agribusinesses through commercial banks from 2008 until December 31, 2016. |

|

Selkhozfond |

Fund housed in the Ministry of Finance responsible for payments for agricultural production, purchasing, and sales. |

|

Soum |

Uzbek currency |

|

World Bank |

The public sector lending arms of the World Bank Group, the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, and the International Development Association. |

|

World Bank Group |

The World Bank Group consists of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the International Development Association, the International Finance Corporation, the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency, and the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes. |

I. Uzbekistan’s Cotton System and the World Bank

Uzbekistan’s Cotton System, Forced Labor, and Past Concerns of Widespread Child Labor

The Uzbek government exerts direct control over the cotton sector from the top down, with officials at every level involved in implementing the forced labor system.[1] Annually the government forces citizens to prepare cotton fields and pick cotton, and farmers to deliver production quotas, all under threat of penalty. A 2014 presidential decree illustrates the close involvement of high-level central government officials in cotton production and harvesting. The decree gives personal responsibility for the harvest to key central officials and regional and district governors, and gives the prime minister authority for the decree’s execution.[2]

Top officials set the national cotton production target each year.[3] The prime minister issues quotas to the regional hokims, or governors, who, with the state-controlled cotton association, responsible for raw cotton procurement and ginning, impose productionquotas on farmers through their land lease agreements and procurement contracts.[4] Farmers, who do not own their land but lease it from the government, are obligated to sell cotton to one of the state-controlled gins at the state price.[5] The Ministry of Finance sets the price paid to farmers below the government’s own estimate of production costs.[6] The government also sets the rates paid to pickers, which are substantially lower than market wages.[7]

The government controls the inputs for cotton production through joint-stock companies, which are co-owned by the government and individuals.[8] These companies have a monopoly over each input or service needed for cotton production. The Ministry of Finance controls the flow of expenditures and income for cotton and cotton seed production through a cashless system of credit managed by the agricultural fund, called the Selkhozfond. According to a credible study of the financial flows of the cotton industry, the Selkhozfond, housed in the Ministry of Finance and controlled by high-level officials, does not publicly report income or expenditures.[9]

The Selkhozfond transfers funds into designated accounts for cotton production at commercial banks and disburses to farmers’ accounts according to the farmer’s purchase contract. Rather than providing cash, banks record payments to the accounts of input suppliers on behalf of farmers.[10] Following the harvest, the Selkhozfond pays farmers for the cotton delivered to state-controlled gins by depositing money into their accounts that must be used to repay the banks, including for interest, before it is used for any other purpose.[11]

Under the authority of the central government and with the support of the commercial banks, officials enforce production quotas assigned to farmers and debts owed by farmers to the government via the banks by confiscating farmers’ land and other property, bringing criminal charges, and using physical and verbal abuse against farmers.[12] In 2015 the government launched an agricultural “re-optimization” plan to reduce the size of agricultural land allotments and to take over land of farmers who failed to meet cotton quotas.[13] It also implemented a plan known as “Cleaver” (Oibolta in Uzbek), under which local officials repossessed the land and possessions of farmers who had failed to meet production quotas for cotton or wheat or incurred debts.[14] The plan and other punitive measures continued in 2016.[15]

On a conference call with local authorities and farmers on October 12, 2015, then-Prime Minister Mirziyoyev ordered local officials to use court bailiffs and police to take property from indebted farmers. A farmer who was on the call told Radio Ozodlik that the prime minister said, “Go to the homes of farmers in debt, who can’t repay their credit, take their cars, livestock, and if there are none, take the slate from their roofs!”[16] In 2016 farmers told the Uzbek-German Forum that they would again face consequences for failure to meet their daily harvest and annual cotton production quotas.[17] One farmer, who only fulfilled 70 percent of his cotton quota in 2016, said, “They will use Shavkat Mirziyoyev’s ‘Cleaver’ regime against me. It was like that last year. I had to sell all my livestock and turn in [the money] instead of cotton.”[18]

The government also appeared to assign new penalties to farmers who fail to meet cotton production quotas in effect for contracts signed as of July 20, 2016. The Uzbek-German Forum obtained a copy of a “Warning Letter” sent to cotton farmers which states that they will be subject to a court proceeding for failure to fulfill the production requirements as well as incur personal financial liability for credit advanced.[19]

The prime minister oversees implementation of the cotton production plan, including through regular conference calls with regional officials and farmers.[20] Regional and local hokims bear responsibility for mobilizing labor to harvest cotton and perform spring fieldwork.[21] These officials, in turn, impose mobilization quotas on public sector officials, such as the heads of the regional and local departments of education and health, and heads of enterprises, to mobilize workers from their sectors. Department heads allocate quotas to school, college, university, and hospital directors who, in turn, require their employees and students, in the case of colleges, universities, and some schools, to perform cotton work.[22] Officials also impose recruitment and harvesting quotas on mahalla, or neighborhood council committees.[23] Officials at every level risk losing their jobs if they fail to deliver their quotas for labor and cotton, and, in turn, threaten their employees with loss of jobs and other penalties if they refuse to work on the cotton fields.[24]

As discussed below, through this chain of command, the government has forced students, in some cases children, teachers, doctors, nurses, people receiving social welfare, and employees of government agencies and private businesses to the cotton fields, against their will and under threat of penalty. [25]

ILO Committee of Experts’ Concerns

Since 2005, the ILO Committee of Experts on the Application of Conventions and Recommendations has expressed concerns about reports of forced and child labor in the cotton industry and the government’s failure to eliminate it in observations under Conventions 29, 105, and 182.[26] In 2016, the Committee once again urged the government to eliminate the use of compulsory labor of public and private sector workers, as well as students, in cotton farming.[27]

Reduction in Child Labor

Prior to 2014, officials systematically forced children to work in the cotton fields, primarily through school officials, although this practice has diminished following sustained international pressure.[28] Child labor began to decline in 2012 after the European Parliament deferred a textile trade deal with the Uzbek government until ILO observers “confirmed that concrete reforms have been implemented and yielded substantial results in such a way that the practice of forced labour and child labour is effectively in the process of being eradicated....”[29] The reduction of child labor accelerated in 2013 after the US downgraded the country to Tier 3 in the 2013 US Trafficking in Persons report.[30] In 2014 the Uzbek government for the first time did not systematically mobilize 16 and 17-year-old college students to harvest cotton.[31]

World Bank and Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan joined the World Bank in 1992. The Bank’s engagement with Uzbekistan’s agriculture sector began with the 1995 Cotton Sub-Sector Improvement Project, which was aimed at liberalizing cotton prices and privatizing the cotton seed industry.[32] Despite the Uzbek government’s resistance to recommendations to open the government-controlled industry, the Bank has continued lending to the sector.[33] The Bank has only acknowledged and sought to address forced and child labor in the sector in recent years.

Complaint Filed Against the World Bank

In September 2013, victims of forced labor filed a complaint with the World Bank’s independent accountability mechanism, the Inspection Panel, alleging that one of its agriculture investments, Rural Enterprise Support Project II (RESP II), was contributing to forced and child labor.[34] The project funded the government to finance farmers and agribusinesses through commercial banks.[35] The complainants argued that the Bank had not fully recognized and analyzed the problem of forced and child labor and had not put in place adequate measures to prevent Bank funding from being used on agricultural lands on which forced and child labor are practiced.[36]

In its initial report, the Inspection Panel noted that “a plausible link does exist between the project and the alleged harms” of forced and child labor and significant issues of policy compliance.[37] In response, World Bank management promised to implement measures to mitigate risks of perpetuating forced and child labor in its projects. Because of these promises, the Inspection Panel did not undertake a full investigation, viewing the proposed mitigation measures as adequate.[38] The complainants strongly disagreed.[39]

New World Bank Group Investments

Since the 2013 complaint the World Bank Group has increased its financing of agriculture projects in Uzbekistan and in 2015 and 2016 was providing US$518.75 million for irrigation and to finance farmers, through commercial banks, to invest in new technology.[40] In addition, the International Finance Corporation (IFC) has loaned Indorama Kokand Textile, $40 million to expand its textile plant.[41] This project has been subject to a formal complaint with the IFC’s accountability mechanism, discussed below.[42]

II. Evidence of Forced and Child Labor and Links to World Bank Group Projects

During the 2015 and 2016 cotton harvests the Uzbek government required farmers to grow cotton and mobilized students, teachers, medical workers, other government employees, and private-sector employees to harvest cotton, all pursuant to government policy and under threat of penalty. The penalties threatened and imposed by a broad range of state authorities included job loss, loss of child welfare benefits and other welfare payments, academic penalties for students, including expulsion from college or university, and threats of prosecution and violence. Regional and local authorities acted under the authority of the central government and relied on the involvement of many people, including mahalla committee chairpersons, directors of schools, colleges, universities, hospitals and medical centers, private and public enterprises, and government agencies, including the tax authorities, police, and prosecutors.

Child labor continued to be a problem during the cotton harvest, despite significant progress in curtailing it. In 2015 and 2016 some schools forced children as young as 10 and 11 years old to pick cotton. Although the government has made policy commitments and issued orders that children should not work in cotton fields,[43] the intense pressure to fulfill quotas led some officials to resort to child labor.

Section A presents evidence of the ongoing, systematic use of forced labor throughout the country’s cotton sector, emphasizing the involuntary nature of the work and the menace of penalty, the two core components of the definition of forced labor. It also presents evidence of forced child labor in certain regions. World Bank-funded agriculture and irrigation projects are being implemented in 10of Uzbekistan’s 12 regions as well as in Karakalpakstan: Andijan, Bukhara, Fergana, Kashkadarya, Khorezm, Jizzakh,Namangan, Samarkand, Syrdarya, Tashkent.[44] Human Rights Watch and the Uzbek-German Forum documented evidence of forced labor in six of these regions as well as in Karakalpakstan.[45] The World Bank does not publicly report which farms in these regions benefit from Bank-financed projects. Similarly, Indorama, which the IFC has invested in, does not report even in the vaguest terms where in Uzbekistan the cotton it processes is grown.[46] Neither Indorama nor the IFC were willing to disclose the districts where the gins from which Indorama sources cotton are located.[47] Due to the widespread nature of forced labor in Uzbekistan, it is highly likely that the government forced people to work on farms benefiting from World Bank Group projects.

The World Bank is loaning the Uzbek government US$260.79 million to improve irrigation in parts of Beruni, Ellikkala, and Turtkul districts in the autonomous Republic of Karakalpakstan.[48] Farmers are required to grow cotton on a significant portion of farms covered by the project.[49] In section B, below, this report disaggregates evidence on forced and child labor specifically from these districts because the defined project area makes it feasible to document labor abuses directly within the project area and because the government committed to comply with laws on forced and child labor in this area.[50] Human Rights Watch and the Uzbek-German Forum found that officials forced adults and, in some cases children, to pick cotton and weed cotton fields in these districts in violation of the government’s agreements with the World Bank. According to its agreements with the government, the World Bank can suspend this loan uponreceiving credible reports of forced or child labor occurring in the project area.[51]

A. Ongoing Evidence of Systematic Forced Labor and Continuing Child Labor in Uzbekistan’s Cotton Sector

In both the 2015 and 2016 harvests, as in previous years, government officials at all levels oversaw cotton production and harvesting, including ordering the mobilization of workers. According to a regional prosecutor, the Cabinet of Ministers issued a protocol on July 20, 2016, which “decreed to involve all employees in the cotton harvest.”[52] Regional and district officials implemented the central government’s orders by imposing labor mobilization quotas on public institutions for cotton picking during the harvest, as well as for planting and weeding in the spring. In addition to labor quotas, government officials required institutions to meet harvest quotas by picking enough cotton or paying money to cover the shortfall.[53] District hokims and law enforcement officials monitored how many

workers each institution contributed and how much cotton each institution delivered at daily cotton meetings.[54]

Officials threatened, or sometimes punished, heads of institutions that did not meet their quota with disciplinary action and dismissal.[55] Heads of institutions threatened employees and students with dismissal, expulsion, or disciplinary consequences to induce them to work, and heads of mahallas threatened residents with loss of benefits, as described below.[56] Some institutions, especially in the health and education sectors, shut down or operated at reduced capacity during the harvests.[57]

In 2016 a farmer told the Uzbek-German Forum that representatives of the government-owned cotton gins in some regions amended their contracts with farmers.[58] The amendments specify that the farmers accept the obligation to comply with Uzbek laws and international obligations, in particular ILO Convention No. 29 converning Forced or

Compulsory Labour and ILO Convention No. 105 concering Abolition of Forced Labour, when recruiting workers to harvest cotton.[59] Considering the government’s control over the cotton sector, including ordering farmers to produce cotton, setting the price for cotton below production costs, setting the price paid to pickers, and in mobilizing and forcing people to work in the harvest, [60] this raises serious concern that such provisions could be used to scapegoat farmers for the use of forced labor. A farmer explained, “[Pickers] don’t come by the will of the farmer. They come on orders from above.”[61] Some farmers told the Uzbek-German Forum that they do not control mobilization or working conditions and risk penalties for failure to harvest their cotton if they refuse workers while the workers, also under pressure to meet quotas, will simply go to work at another farm.[62]

Extract from Transcript of Cotton Meeting in Khazarasp, KhorezmHokim, Uktam Kurbanov: Cotton! You have to go and pick cotton and fulfill the norm. Is it clear!?.... This policy applies to everyone! If even one person does not go out, it will be bad for you! I’ll shut down your organizations! Everyone, without exception, whether from the hokimiat, tax authorities, the bank or other organizations, all will be shut down. Come on, Bank, answer. Bank Administrator: Boss, all of our workers went to the harvest. Hokim: Then everything is fine, everybody went to the harvest, everything is fine. Bank Administrator: Boss, all of our employees delivered 50 kilograms per day.... A bus with 65 to 70 people leaves to the cotton fields every day. Hokim: The plan has not been fulfilled!.... Everyone should go to the cotton! No one should stay home! Sanitary-Epidemilogical Station.... What’s this? You delivered only 1,286 kilograms? Why is that? I’ll tear your head off! Source: Transcript of Cotton Meeting in Khazarasp, Khorezm, September 29, 2015, on file with Human Rights Watch and the Uzbek-German Forum. A link to the original audio recording is available at http://eltuz.com/ru/glavnye-temy/277/ (accessed May 25, 2017). English transcription is available at http://harvestreport2015.uzbekgermanforum.org/pdf/Local-City-District-Administrations/2015.09.29_Transcript-of-a-Recording-of-a-cotton-headquarters-meeting.pdf (accessed May 25, 2017). |

Field research, official government mobilization decrees and labor tracking ledgers, statements by officials, social media postings, and local media reports indicate that government officials required public institutions to send a large proportion of their employees at a time to pick cotton.[63] Institutions included kindergartens, schools, colleges, universities, local government administrations, clinics, hospitals, and government enterprises. In some institutions, this meant that all employees were sent to pick cotton at some point during the harvest.[64]

The government also required companies and small business owners to provide workers or to pay.[65] For example, in 2016 the Uzbek-German Forum visited three Hamkorbank branches during the cotton harvest. At one branch, the Uzbek-German Forum was advised that about 30 employees of the bank had been sent to pick cotton.[66] At the other two, the Uzbek-German Forum was advised that the bank had paid to avoid sending employees to the cotton fields because to do so would limit the bank’s ability to provide services.[67]

In 2015 the government also ordered the mobilization of third-year college students and university students of all years to harvest cotton, in some cases even when those students were only 17 years old.[68] In 2016 the government continued to mobilize university students of all years, but the Uzbek-German Forum only documented the mobilization of third-year college students in Andijan, Fergana, and Kashkadarya during class time, including some who were 17 years old.[69]

The ILO determined from survey data that 2.8 million people participated in the 2015 harvest.[70] On the basis of this data, the ILO suggests that approximately two-thirds were recruited voluntarily, a “minority recruited involuntarily,” and the remaining were “to some degree reluctant,” due to poor working conditions and wages.[71] Given present conditions, there is every reason to suspect that many of these “reluctant” workers—quite possibly a large majority—cannot be considered voluntary.

Human Rights Watch and the Uzbek-German Forum believe that the number of forced laborers is likely significantly higher than the ILO estimate for the following reasons. First, the ILO’s figures should be read with due regard to the government’s widespread coaching of Uzbek citizens to tell the ILO and others that they participate in the cotton harvest voluntarily.[72] Second, as discussed below, with few exceptions, when interviewed in a confidential setting, people told the Uzbek-German Forum and Human Rights Watch that they did not undertake this work voluntarily, reluctantly, or due to social pressure, but rather because the government required it of them and if they refused, they were told explicitly or reasonably believed they would be punished. It is quite possible that a significant proportion of the people the ILO interviewed did not feel comfortable alleging that they had been forced to work out of fear of reprisal.

Public sector employees, who are among the lowest paid in the country, and people living in poverty are particularly susceptible to forced labor, as they are as they are unable to risk losing their jobs or welfare benefits by refusing to work and cannot afford to pay people to work in their place. Some have personal connections to local officials and are not asked or are excused from working in the cotton fields.[73] A college teacher explained that a few privileged teachers are excused from working in the cotton harvest because they are related to influential government officials, and even the collegе director “can’t talk to them.” “Ordinary teachers” have to pay for a replacement worker or go to the cotton fields, she said. Otherwise “they are dismissed.”[74]

Responses to the ILO’s Conclusion that Most Cotton Pickers are Voluntary, Many Reluctant, Few InvoluntaryHuman Rights Watch shared with several interviewees who had been forced to work in the 2016 cotton harvest the ILO’s conclusion that two-thirds of cotton pickers were voluntary and the remaining were to some degree reluctant, with a minority recruited involuntarily. Below is how some of them responded to this information:

|

Involuntary Labor

While many people may accept cotton picking or spring fieldwork as the “cost” of employment in Uzbekistan, this should not be mistaken for voluntariness. In the vast majority of interviews conducted in private, with a promise of anonymity, people described working in the cotton industry because of state-led coercion, emphasizing the real threats of loss of employment or social welfare benefits, or academic difficulties.[75] With few exceptions, they did not point to patriotism, social pressure, or desire to earn supplemental income as their motivation.[76] One Uzbek-German Forum monitor, who works undercover, spoke of three exceptions.[77] First, replacement workers, who are paid both by those they are replacing and the farmer they are picking for. This often includes unemployed rural residents. Second, people who work for the farmer and those that sublease land from the farmer. Third, a minority of low-paid public sector employees who are efficient cotton pickers and can gather large amounts of cotton, early in the season, resulting in an additional bonus from farmers. In a rare example, a kindergarten teacher explained that while her school director ordered her and her colleagues to pick cotton and told her that she would be punished if she did not, she would still go if she had a choice because she is highly efficient at picking cotton and enjoys it.[78] Most, however, emphasized that they did not pick cotton to supplement their income, but because they were forced.[79]

Cotton is most abundant from early to mid-September, when approximately 75 percent of cotton bolls open. [80] As a result, most voluntary labor occurs during this period, when earning potential is higher and working conditions are better. Thereafter, many workers are able to earn very little and are in the fields involuntarily.[81]

Public sector workers and students emphasized the involuntary nature of their labor in the cotton fields.[82] Unless people had relationships with government officials or the head of

their institution, people who did not wish to pick cotton could only avoid it by directly hiring and paying a replacement worker to pick cotton in their name or by making a payment to an authority, usually a supervisor or administrator.[83] Parents who did not want their children to pick cotton had little recourse and faced threats.[84] When the mother of a third-year college student who was ordered to pick cotton kept him home for two days to help her with domestic chores, the college sent a teacher to bring him back to the fields.[85] Several people emphasized that pregnant women or people who became ill while picking were not exempted from cotton picking.[86] A woman described working in the harvest because her niece, a college student, had become sick after picking cotton for a month.

The student’s parents told the university that their daughter was sick, but teachers visited their home to force her to continue working so her aunt went in the student’s place.[87]

Workers expressed a strong preference to remain at their regular jobs.[88] A former Andijan mahalla official explained,

The government pays your salary so you will pick or you could be asked to give up your post. Now, there is no work ... so you can’t refuse [to pick cotton], you are obligated.... What kind of fool would go to work in the dirt in the cotton fields on a cold day of his own accord instead of sitting inside in a nice warm office? To understand that [picking cotton] is mandatory, you don’t have to be a genius and solve puzzles.... We say, ‘cotton is the people’s khashar [communal work].’ But for real khashar ... you go if you want but if you don’t your neighbor doesn’t threaten ‘you’ll come or else I will do something against you.’[89]

Law enforcement officials supervised the cotton fields, escorted workers, and participated in cotton meetings. Law enforcement, including police, National Security Service (known by its Russian acronym SNB), and prosecutors assisted in mobilizing and supervising workers and enforcing quotas in 2015 and 2016, as in past years.[90] For example, a college teacher said that parents who did not allow their children to pick cotton would have to answer to the prosecutor.[91] A nurse said that police accompanied mahalla officials going house to house to send people to the fields.[92] A police officer threatened to shut down the business of a shopkeeper who refused to pick cotton, telling him he had no right to refuse the government’s orders.[93]

People told Human Rights Watch and the Uzbek-German Forum that law enforcement officials supervised them as they gathered in town centers to be transported to the cotton fields, during the evenings following a day’s work, and in the cotton fields, supervising from a tent (shipon) in the center of the field to ensure that people were working and to help enforce quotas. A kindergarten employee said that she was afraid to use the complaint hotlines because she feared repercussions from the prosecutor, who assisted the hokim in organizing and supervising fieldwork and insulted workers who did not meet the quota.[94] Law enforcement officials also interfered with independent monitors documenting the cotton harvest, including by removing them from fields and destroying notes and photographs.[95]

Penalties and Threats of Penalties for Refusing to Work

Public sector workers, students, and pensioners emphasized that they worked in the cotton fields because they had been threatened with punishment, often explicitly. Even when people did work in the cotton harvest, if they fell short of the required picking quota they were deemed to have not worked hard enough and punished.

University and college directors and teachers threatened students who attempted to refuse to pick cotton or who did not fulfill the picking quota with academic difficulties, including expulsion, and public shaming.[96] Some students and public sector employees were required to sign statements agreeing to pick cotton and to fulfill quotas or agree to suffer expulsion, dismissal, or other sanction.[97] In September 2016 a university student told Human Rights Watch and the Uzbek-German Forum that she refused to pick cotton or hire a replacement worker.[98] After refusing to pay a bribe to one of her teachers, who offered to include her name in the list of cotton pickers for a price, university officials called her daily and sent her numerous text messages pressuring her to “resolve the cotton question,” and threatened to expel her.[99] Because of the pressure, the student eventually paid an unemployed person to work in her place.[100]

A student at another university also received a text message warning, “Respected master’s students! You must resolve your participation in the cotton harvest within one hour. Today we are compiling information and you are at risk of expulsion. Immediately resolve this issue.”[101] Four students in Kokand told a journalist that they were expelled for avoiding the harvest or requesting exemption from cotton picking, in three cases because they needed to work at better-paying jobs to support their families.[102] College and university teachers said they try to scare parents with threats that their children will be expelled or held back a year unless they pick cotton.[103] First-year university students in Jizzakh told the Uzbek-German Forum that university deans threatened them with prison if they refused to pick cotton for the university.[104]

All teachers interviewed by the Uzbek-German Forum said that officials threatened them should they refuse to pick cotton, usually with dismissal.[105] For example, a college teacher from Syrdarya said, “Refusing to pick cotton amounts to giving up your job.”[106] A kindergarten teacher was dismissed because she and her husband were both ordered to pick cotton by their directors for overnight shifts at the same time, which would leave no one at home to care for their children. When she requested to change her shift, her director gave the teacher the choice to go as ordered or pay 700,000 soum (US$106). As she was unable to pay or leave her children, the director forced her to resign.[107]

Healthcare workers similarly picked cotton or paid for replacement workers against their will and under menace of penalty, usually dismissal.[108] A video sent to Ozodlik shows the head nurse at a clinic threatening nurses with dismissal if they fail to pick the daily quota and making them sign statements agreeing to “any action” against them if they fail to meet the quota.[109] Two doctors told the Uzbek-German Forum that authorities ordered medical staff to sign two statements before they went to the fields. The first statement said, “I [name] undertake the obligation to participate in the cotton harvest of my own volition. If I do not fulfill the obligation I have undertaken, I agree to submit to any disciplinary punishment.” The second, which would be used should anyone who refused to pick cotton or hire a replacement worker, said, “I [name] request to resign from my job of my own volition.”[110]

Regional and district officials threaten the heads of institutions with the loss of their jobs if they fail to deliver quotas and the heads of institutions threaten their staff.[111] A school director said that he risked the hokim and education department punishing him: “At cotton meetings we are told to write our resignations if we don't want to pick cotton and can't get our staff to pick.”[112] Another said that the hokim threatened to detain him at the hokimiat that day if he did not turn in one ton of cotton.[113]

Mahalla councils recruited people to pick cotton by threatening to withhold child benefits and other welfare payments, and access to public utilities.[114] A mahalla employee explained, “Every day the mahalla needs to send 60 people to the harvest. The easiest way is to send people who come to the mahalla committee to get necessary papers and forms, [if they refuse to pick,] we refuse to give them the papers. They have no alternative—they are forced to pick.”[115] Another mahalla employee said that officials at the hokimiat told the mahalla employees to threaten to withhold people’s child welfare payments to coerce them to pick cotton.[116] Several women confirmed that they only picked cotton because their mahalla committee had ordered them to and threatened to withhold their child benefits if they refused.[117] Another mahalla committee employee said, “On [name withheld] street, no one went to pick cotton and no one gave any money. People from the electric utility came and cut all the cables between the two poles [on the street], threw them in the truck and drove away.”[118]

Senior management at some businesses also threatened employees with loss of jobs or other disciplinary measures if they refused to pick cotton, and local authorities pressured entrepreneurs to participate in the harvest, threatening them with fines, burdensome inspections, and revocation of licenses.[119] Assia Shatilova, a shopkeeper in Chirchik, in the Tashkent region, told the Uzbek-German Forum that she refused to pay 750,000 soum (US$125) to support the cotton harvest in autumn 2015. She said that in retaliation, on December 29, 2015, local police and tax inspectors, accompanied by the deputy hokim, illegally confiscated 85 million soum (US$14,167) worth of inventory, without any paperwork. She said that an officer shoved her, injuring her. On March 28, 2016, tax inspectors returned to conduct an inspection and confiscated the rest of her inventory, forcing her to close her business and leaving her family without a livelihood.[120]

Ongoing Child Labor

In 2016 children and teachers in two districts in Kashkadarya and a school employee in Fergana told Human Rights Watch and the Uzbek-German Forum that local officials required schools to mobilize children as young as 10 or 11 years old to pick cotton and suspended classes during this period.[121] They noted that in several districts this was worse than 2015, when children received some classes prior to being sent to pick cotton.[122]

- In Yakkabog district, Kashkadarya, children in grades 7-9 (approximately ages 12-14) picked cotton for most of the season, and children in grades 5 and 6 (approximately ages 10-11) picked for more than a month.[123]

- In Shahrisabz district, Kashkadarya, children in grades 6-9 (approximately ages 11-14) picked cotton every day from September 20 to November 1, while children in grade 5 (approximately age 10) picked for 3 or 4 days.[124]

- In Nishon district, Kashkadarya, Radio Ozodlik reported that children in grades 5-9 (approximately ages 10-14) at several schools picked cotton.[125]

- In a rural Fergana school, grade 8 and 9 (approximately ages 13-14) students were forced to pick cotton every day for about a month, while younger students were sent for 15-20 days.[126]

- In Andijan some schools required parents to pick cotton in the place of their children or pay 10,000 soum (US$1.50) per day.[127] A nurse in Andijan said that in her nephew’s school parents could pick cotton for their children or pay for it instead.[128]

In contrast, in Fergana region, one woman said child labor was prohibited on the farms where she picked cotton.[129] Two teachers emphasized that children could not be anywhere near the fields because the ILO inspectors could find out.[130] However, an education worker at a rural Fergana school described being ordered by the school director to force children in grade 5 and older (approximately age 10 and older) to pick cotton.[131]

In 2015, a girl in grade 7 told the Uzbek-German Forum that her school in Andijan sent all children in grades 1-9 (approximately ages 6-14) to pick cotton after school, on weekends, and occasionally suspended class for children to pick cotton.[132] She said that parents picked in place of first-graders.[133] A father in Shahrisabz told the Uzbek-German Forum that schoolteachers ordered children in grade 9, who are usually 14 years old, including his daughter, to pick cotton at first only on weekends, then also on Fridays and, then every day for several hours after classes.[134]

Human Rights Watch and the Uzbek-German Forum documented cases where 16 and 17-year-old college students also picked cotton in Kashkadarya, Jizzakh, Fergana, and Andijan in 2015 and 2016.[135] In many of these cases, officials appeared to resort to child labor to fulfill the college or school’s labor recruitment or harvesting quotas. For example, a college teacher from Jizzakh said that when the college could not fulfill its recruitment quota of third-year students, it supplemented with second-years. The teacher said, “We made up the deficit by sending second-years to the fields in two groups, so it wouldn’t be noticeable. In case the ILO were to come in suddenly, it would look like the second-years were studying.”[136] One college teacher told Human Rights Watch that in 2015, her college only took children to pick cotton after the ILO had completed its inspection.[137] A parent in Jizzakh said that children from the Lyceum (ages 16-18) picked cotton in their teachers’ names.[138]

Education workers emphasized that they were required by their school directors to mobilize students, under great pressure from “higher authorities.”[139] A teacher and a parent questioned the meaningfulness of child labor laws, as the children were still forced to work under orders “from above.”[140] Another teacher said he and his colleagues had to force most of the students to work in the cotton fields.[141] According to a parent, the director of her 17-year-old daughter’s college threatened her when she attempted to refuse to allow her to pick cotton, saying he would report it to her employer—a commercial bank benefiting from IFC support—for disciplinary action.[142]

B. Forced and Child Labor in Beruni, Ellikkala, and Turtkul, Karakalpakstan

Human Rights Watch and the Uzbek-German Forum found that government officials imposed cotton production quotas on farmers and mobilized public sector workers, including school and college teachers and medical workers, and large numbers of third-year college students (who are typically age 18) from Beruni, Ellikkala, and Turtkul districts in Karakalpakstan to harvest cotton in fall 2015 and 2016 under threat of penalty. Regional and district hokims issued quotas for cotton production, harvesting, and labor mobilization to farmers and institutions.[143] Officials from the departments of education and health issued quotas to the directors of schools, colleges, universities, hospitals, and clinics, who, in turn, required their employees and students to pick cotton or pay for a replacement worker.[144] Other local government officials, including mahalla committee members and tax authorities, coerced labor or payments from people receiving benefits and business owners.[145]

Information gathered from visits to colleges, schools, hospitals or clinics, and local administrations, markets, and mobilization sites, and cotton fields in each of the three districts, interviews with 114 people forced to grow, pick, or weed cotton, observation at mobilization sites, and review of local media suggest that the government mobilized thousands of public sector workers at a time, including college teachers, schoolteachers and healthcare workers, for the duration of the 2015 and 2016 harvests in these three districts.[146] These findings are corroborated by official mobilization decrees and government documents that track mobilization and picking quotas from other regions, announcements in local press, and statements by officials, and are consistent with findings in all other regions monitored by the Uzbek-German Forum in 2015 and 2016.[147] During the 2016 harvest the Uzbek-German Forum interviewed and saw several 13 and 14-year-old children harvesting cotton who described working under the direction of their schools, as discussed below.[148]

Public sector workers generally picked cotton in shifts of 10-25 days and in some cases longer, often staying in temporary housing and, after their return, worked daily shifts before or after work and on weekends in addition to their regular jobs.[149] People could avoid picking cotton by paying a replacement worker or sending a relative to pick cotton in their place.[150] Local government officials in all three districts also required some public and private sector businesses to send employees to pick cotton or make payments, purportedly to hire cotton pickers.[151]