Summary

Food insecurity and poverty are enduring problems in Spain. Just over a decade ago, the 2008 global financial crisis sharply exacerbated both food insecurity and poverty. And just as people’s living standards seemed to improve, the Covid-19 pandemic and its economic impact have made both poverty and food insecurity worse once more.

At the start of the pandemic, the Spanish government expanded existing unemployment support programs and introduced a new flagship social assistance program. However, despite the government’s stated good intentions, existing weaknesses and flaws in the social security system, as well as problems in the design of new forms of assistance, meant that support fell short of what was needed. Limitations on the scope and eligibility of both existing and new measures have meant that many people still depend on non-governmental food aid to feed themselves and their families, and struggle to meet their basic needs. As a result, Spain’s government is failing its obligations to protect and fulfil people’s rights to food and an adequate standard of living.

Spain was no exception to the devastation of the Covid-19 pandemic.

As of June 13, 2022, more than 107,000 people had died with or of Covid-19, and there had been almost 1,700 Covid-19 related deaths during the prior month. Beyond the immense human toll and its effect on the general population, the public health protections that significantly restricted activity imposed during a nationwide lockdown and resulting economic closures have wreaked havoc on people living in or near poverty.

Many people in Spain already experiencing poverty were left further exposed to a complete loss of income and lack of access to adequate food. Others, previously employed and living above the poverty line, found themselves suddenly out of work and struggling to access a social security system, which was overwhelmed by demand. As incomes slowed to a trickle, people began to fall behind on monthly payments and to go hungry. The sight of food queues at churches, neighborhood associations, and community centers, with shopping carts left in orderly lines in anticipation of food distribution, became commonplace.

At a minimum, tens of thousands of people living in poverty have faced violations of their right to an adequate standard of living, and difficulties securing their rights to food and social security and social assistance during the pandemic.

The government took some important steps to address the sudden loss of income for so many, expanding an existing furlough program (ERTE, the Spanish acronym for an existing labor code provision for temporary work reduction) expressly for the Covid-19 pandemic, and fast-tracking the introduction of the Minimum Vital Income (IMV, ingreso mínimo vital), a social assistance scheme planned before the pandemic whose introduction was brought forward to May 2020. The IMV was not a basic income scheme, but rather a non-contributory social assistance program. Spain is a relative latecomer among European countries to having a nationwide social assistance program. Both the expansion of ERTE and introduction of IMV were intended to complement the existing social security system.

However, these schemes were insufficient to compensate for the weakness of the social security system and fell short of meeting people’s needs, leaving them instead to rely on food aid. The Spanish state provided emergency food assistance delivered through the EU’s Fund for European Aid to the Most Deprived (FEAD). However, this fell short of demand, leaving charities and community organizations to fill the gap.

The Minimum Vital Income scheme, which, as of June 2022, allowed applicants to claim between €491 and €1,081 per month based on household size, while admirable in its objectives, proved extremely difficult to access due to stringent eligibility criteria and documentation requirements. Investigative journalists have discovered that exclusions baked into the system, some of which are evidently arbitrary, as well as a system overwhelmed by demand, may have contributed to very high rates of refused applications. Studies of official social security data show that three quarters of applications for IMV were rejected. Moreover, the levels of support are inadequate to meet basic needs.

Applicants in the autonomous communities of Spain with similar or complementary minimum income schemes also faced difficulty accessing these supports as regional and central governments were slow to work out precisely what applicants were entitled to and ensure the allowances were compatible. There is a great degree of variance in autonomous communities’ policy on providing such non-contributory social assistance, including levels of support and eligibility criteria.

The ERTE furlough support left out people working in the informal economy (estimated to be approximately 20 percent of the total economy by informed journalists, and 11 percent according to official sources). ERTE furloughs did not adequately cover the lost income of people who work seasonally, or people who are paid in part under the table.

Some groups have been disproportionately affected by the economic impact of the pandemic and inadequate state response. Data and surveys by nationally-recognized civil society organizations such as Oxfam Intermón, Caritas, Save the Children Spain, smaller single-issue-focused organizations, and Human Rights Watch research, indicate that families with children, older people dependent on state pensions, migrants and asylum-seekers with precarious legal status, and people working in sectors where informal employment is common such as hospitality, cleaning, care, and construction have been hit particularly hard during and since the initial economic shutdown.

Single parents (of whom estimates indicate 8 in 10 are women) reported to Human Rights Watch that they skipped meals to ensure their children had enough to eat. Pensioners we interviewed said that social security support which was not adequate prior to the pandemic was now even less so as the price of food and other essential items increased, and that they would not be able to manage without food aid. Pensions finally increased in 2022 in line with the consumer price index, almost two years into the pandemic, as Spain, like other countries, confronted a cost-of-living crisis.

Apart from people seeking asylum and people reliant on age-related pensions, almost all those interviewed by Human Rights Watch who received food aid said they had not relied on food banks or other charities for food prior to the Covid-19 pandemic. Many expressed surprise that they were having to seek food aid and reflected on how their situation had been better prior to the pandemic.

Food bank organizers interviewed by Human Rights Watch observed that their food distribution data showed a sharper rise in demand for food aid during the Covid-19 pandemic than during the years following the 2008 global financial crisis, and outlined their fears about demand levels remaining high once the pandemic-related furlough support ends.

Under human rights law the Spanish government and regional authorities in Spain have obligations to ensure that everyone can access adequate food, and that people are guaranteed an adequate standard of living, including through its social security system. These rights continue to apply during a crisis, including the Covid-19 pandemic.

Human Rights Watch’s findings, based on research in the autonomous communities of Madrid and Catalonia, reflect that despite efforts to provide support, the Spanish state failed to protect people’s rights to food and an adequate standard of living during the pandemic. Human Rights Watch interviewed people who had applied for IMV, as well as regional minimum income schemes in Catalonia and Madrid, people receiving ERTE support, age-related pensions, and/or disability benefit, asylum-seekers receiving limited support, and people with no social assistance at all.

This failure was exacerbated by a social security system which was uneven in coverage depending on region and type of benefit, and a largely absent national social security and assistance system (beyond non-contributory pensions) prior to the pandemic. The first wave of office closures during the pandemic laid bare the fragility of the social security system’s architecture and its inability to cope with backlogs and demand for the new IMV program.

As a result, people went without adequate income from social security support (contributory social insurance schemes) and social assistance programs (non-contributory cash transfers to ensure subsistence), in some cases for several months, and faced inevitable hunger as their money ran out. This happened despite the government’s efforts to accelerate the deployment of its flagship IMV promise as part of its set of policies to mitigate the economic impact of the pandemic. A slow bureaucracy and high levels of refusal of IMV applications contributed to the problem. There was also confusion regarding how the national IMV scheme would interact with regional social assistance programs administered by the autonomous communities.

The Spanish government should speed up its process of assisting people on low incomes who need to access the IMV and make the application process more efficient, as well as make it possible for people to access emergency support irrespective of migration, residency or employment status.

The Spanish government should reassess and revise (age-related) pensions, and the Spanish and autonomous community governments should similarly revise and reassess other social security support rates, indexing them transparently to cost-of-living measures, to ensure that recipients of such assistance can access and afford adequate food. The autonomous community governments should also take concrete steps to reduce their social services departments’ reliance on referring people in need to sources of charitable food aid, and instead ensure that people signposted to such services can access and afford adequate food.

Despite its stated intentions, as it currently stands IMV runs the risk of being a social assistance program that offers too little, too late, and to too few. If the government acts boldly to make significant reforms of the IMV, and social security support more generally, and embed in domestic law protections for specific socioeconomic rights, including the right to an adequate standard of living and to food, it has an opportunity to ensure a better and fairer outcome for people in Spain and to give them the economic resilience to weather future crises.

Recommendations

The national government of Spain should:

- Take concrete steps to enshrine in domestic law the right to an adequate standard of living as an integral part of its domestic constitutional framework, and to ensure that the right applies to everyone regardless of immigration status;

- Take concrete steps to enshrine in domestic law the right to food, as an integral part of domestic constitutional obligations on social security, children’s rights and rights of older people receiving pensions, and to ensure that the right to food applies to everyone regardless of immigration status;

- Consider taking efforts to amend article 53(3) of the Constitution in order to ensure that the social and economic rights contained in Chapter Three of the Constitution enjoy the same level of guarantee as the rights set out in Chapter Two, which are binding for all public authorities.

- Update the 2019-2023 National Strategy for Preventing and Fighting Poverty and Social Exclusion (March 22, 2019) as a matter of urgency to account for the increase in poverty during, and as a result of, the Covid-19 pandemic;

- Remove undue bureaucratic and other barriers to access to the Minimum Vital Income for those in need, including by:

- Improving the staffing and electronic appointment system of the social security offices dealing with Minimum Vital Income applications, in terms of availability of appointments and in-person assistance, so it can keep up with the demand;

- Increasing assistance to access for people seeking Minimum Vital Income who are socioeconomically vulnerable or face difficulties accessing digitized application systems, including through in-person or telephone appointments to allow people to make their applications in an efficient manner and in a way that avoids applications being rejected for being incomplete;

- Making the criteria for Minimum Vital Income more inclusive, especially during periods of declared crisis or emergency, by for instance:

- removing residence and immigration status barriers;

- expanding coverage to 18 to 22-year-olds;

- lifting arbitrary independent living requirements; and

- ensuring that future crisis or emergency planning for social security support contain measures to make the aid inclusive;

- Improving communication with the relevant social security administrations of the autonomous communities to ensure that people’s access to Minimum Vital Income is not delayed or denied because they are in receipt of other support from their autonomous community (e.g. RMI in Madrid, or RGC in Catalonia);

- Investigating the high reported rate of rejection of applications for Minimum Vital Income support, and remedy any shortcoming(s) found in the investigation;

- Issuing clear guidance to IMV decision makers that refusing applications for insufficient documentation where the document is already held by the national or a regional administration is not acceptable;

- Review and reassess if existing rates of social security support, including Minimum Vital Income, unemployment support and pensions (age-related, disability-linked and other), whether contributory or non-contributory, are sufficient to:

- guarantee the right to an adequate standard of living;

- ensure that no recipient of such social security support or their dependents are left in a situation where they have to go hungry;

- Commit to ensuring that social security support rates beyond pensions will be indexed transparently to cost-of-living indices, including the cost of food and utilities;

- Publish regular and recently updated information about the usage of EU Fund for Aid to the Most Deprived resources for food aid distribution, including statistical information on beneficiaries of such support disaggregated by age, gender, marital status, and number of dependent children or others;

- Ensure that future crisis planning reduces eligibility barriers for emergency social assistance to an absolute minimum.

The autonomous communities of Madrid and Catalonia should:

- Better coordinate with the national government to ensure that delays and obstacles in accessing essential social security support are addressed, and that the existence of a type of social security support (or entitlement to such support) is not used as a pretext to dismiss an application for Minimum Vital Income;

- Commit to ensuring that social security support rates will be indexed transparently to cost-of-living indices, including the cost of food and utilities, and sharing good practice with other autonomous communities and the central government where this is already the established practice at autonomous community level;

- Increase assistance, including through in-person or telephone appointments, provided to people who are socioeconomically vulnerable or face difficulties accessing digitized application systems, and are seeking Minimum Vital Income, similar alternate support from the autonomous community, or both;

- Temporarily lift any barriers which may exist under autonomous community law or regulations which preclude people from accessing emergency social security support during a period of acknowledged crisis on grounds of their immigration status or residency, and ensure that crisis or emergency planning includes such a measure.

The UN Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights should:

- Consider issuing a formal, public assessment of Spain’s Minimum Vital Income scheme, including the adequacy of levels of support, the accessibility or availability of such support, any gap between stated and attained reach, and fairness of eligibility requirements in human rights terms.

- Consider continuing a process of written correspondence with the relevant Spanish authorities to follow up on the observations of his predecessor in relation to the failures of the Spanish social security and social assistance system in tackling poverty.

Methodology

This research is the first in a series of investigations Human Rights Watch is carrying out in Europe into people’s rights to an adequate standard of living, incorporating their rights to food and to social security, including in the context of the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic and the rapid increase in cost-of-living being experienced globally. The overall objective is to identify rights-based recommendations and policies that can inform efforts to ensure that social security systems meet the needs of everyone in society and are sufficiently resilient to deal with future crises, based on some of the lessons learned from state responses to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Human Rights Watch interviewed 52 people receiving emergency food assistance: 24 in Barcelona in June 2021, 23 in Madrid in October 2021, and another 5 in Madrid in January 2022. We also interviewed 22 food aid NGO staff or volunteers, academics experts, and neighborhood and migrant community food aid organizers across Spain between November 2020 and January 2022, initially conducted remotely while Spain’s “state of alarm” restricted movement, and subsequently in-person.

The in-person testimony focused on four neighborhoods in Barcelona (El Raval in Ciutat Vella district, Sant Antoni in Eixample district, and Verdum and Porta in Nou Barris district) and three in Madrid (San Diego and Palomeras Bajas in Puente de Vallecas district and Lavapiés in the Central district)—widely acknowledged as areas of significant social deprivation.[1] Data show these areas were affected particularly by the pandemic, in line

with general patterns around the socioeconomic determinants of health outcomes.[2]

In addition to Spanish national social security provision, this research makes reference to social assistance systems specific to the cities of Barcelona and Madrid, and the autonomous communities of Catalonia and Madrid. References to these local or regional arrangements may not have direct relevance to other parts of Spain.

Interviews were conducted in Spanish, except for one in Catalan and one in English. All in-person interviews were conducted in line with organizational policy on safety and security in the context of pandemic. Real full names of interviewees were used where possible, and where the interviewee granted explicit, informed consent. Some interviewees preferred not to use their full name, in which case surnames are withheld. Any name that is a pseudonym is indicated as such in the footnote. The age provided for each interviewee and their family members relates to the age on the date of interview. All footnotes to quotes from interviews are to interviews conducted in person, unless indicated otherwise.

During March and April 2022, Human Rights Watch contacted Spain’s Ministry of Inclusion, Social Security and Migrations, and the Ministry of Social Rights and the 2030 Agenda, as well as the Autonomous Community of Madrid’s Department of Family, Youth and Social Policy and Catalonia’s Department of Social Rights, with a summary of our findings and questions for each body. In April, the Secretary General of Inclusion and Social Prediction Policy and Objectives from the Ministry of Inclusion, Social Security and Migrations responded in writing. In June, the Office of the Counselor for Social Rights of the Catalan regional government also responded in writing. The other two official agencies contacted had not responded as of June 22, 2022.

I. Poverty Exacerbated by the Pandemic

The immediate impact of the Covid-19 pandemic in Spain in terms of infections and deaths was severe. In March 2020, the Spanish government declared a “state of alarm,” and imposed public health protection measures that included limitations on movement and economic activity to prevent the spread of the virus.[3] These policies had a significant negative impact on economic activity as many places of work and schools closed, movement outdoors was severely restricted for several weeks, and all business categorized as non-essential—restaurants, retail stores, cultural activities, and recreation—ground to a halt.[4] Businesses that were allowed to remain open saw a significant reduction in clientele and income as people’s movement and ability to engage in day to day purchases was limited, while many businesses chose to close their doors in fear or caution in the early wave of the pandemic.

The economic impacts of the pandemic pulled a new set of people into poverty and led to a rise in food insecurity, notwithstanding mitigating measures implemented by the state and national, local and community efforts to provide food aid. Policy responses to the pandemic also exacerbated the poverty that many—including older people receiving age-related pensions, families with children living on low incomes, and people with precarious or irregular immigration status—were already experiencing prior to the pandemic and subsequent economic shutdown.[5] The outcome was a deterioration in people’s enjoyment of their economic and social rights.

The first affected were those working on shift-based cash-in-hand jobs, followed by service industry workers, and later those in other areas of low-wage employment. People working in the informal economy making a living off street-vending or domestic cleaning, for example, could no longer go out to earn a living.[6] Many of these people turned to food banks to help them get by.[7]

The Newly Impacted: Hospitality Sector Workers

The near-complete economic closure of key sectors of Spain’s economy—tourism, hospitality, and entertainment in particular—for weeks, followed by staggered reopening, and further periods of closure, left many people working in them without income. It is common work practice in these sectors to have seasonal (short-term) contracts, which do not give rise to same sort of unemployment support (paro) in the event of a layoff as a permanent contract would. Many people working in these sectors make up Spain’s “new poor.” In Spain, women are also more likely to be employed in the hospitality sector, and so were disproportionately impacted by the pandemic-related fall out in this sector, as both the number of jobs and hours of work available fell.[8]

Ana Belén, 42, a Spanish woman from Palomeras Bajas in Madrid’s Puente de Vallecas district, used to run a bar in the nearby San Diego neighborhood, which went out of business when the pandemic struck. She lives with an adult son, who is not in employment, and a 6-year-old daughter.

I receive the IMV. It’s €465 each month. Our rent is €600. We can’t buy anything. Every month begins with a debt. There is nothing in the fridge. I can’t put in words what the impact of that on me is. I can’t even say it.[9]

Karima, 38, a Moroccan woman who has been in Spain since 2003 and who regularized her immigration status in 2009, lives with her 42-year-old husband, who is a builder, and 8-year-old daughter. She was working in a restaurant prior to the pandemic. Neither she nor her husband was earning at the time of the interview in October 2021, and they reported receiving €412 IMV per month as a family, and some bags of food from social services, but no unemployment support. She described her family’s situation while queuing outside a Caritas food distribution at San Ramón Nonato Parish in Puente de Vallecas, Madrid:

We eat a midday meal every day, but we often don’t have the evening meal. Our daughter eats and we eat if we can, or we sleep and manage without food. We tell ourselves it’s not hunger, you can make a little rice and manage. We feel rejected. We’re experiencing hunger. We are having a bad time of it.[10]

Otman, 50, a Sahrawi man, lives in the Raval district of Barcelona with his wife and their two children, a 4-year-old boy and a 6-month-old girl. His 78-year-old uncle also lived with them until recently moving into institutional care. Otman was a cook in a university residence until the pandemic began, and has been on furlough ever since. He and his family were awaiting an eviction hearing the day after the interview. He spoke to Human Rights Watch while waiting for food distribution at the Church of Saint Augustine in Raval:

I was earning well as a cook, €1000 a month, never needed any help before the pandemic. For three months we lived off our savings. In August [2020] I got ERTE [furlough] at 70 percent, but this doesn’t let you reach the end of the month. We’ve now decided not to pay rent, we have to eat, that’s more important. […] We’ve stopped buying meat, or sometimes we buy some ground meat or bones. We can’t eat fish because of the price. You no longer enjoy any meals. The child eats first. We eat what’s left after. We eat less protein. I’m a cook, I know every meal is missing something.[11]

Ana María Ametller Hueto, 42, a Spanish woman, was living in the Porta neighborhood of Barcelona with her 6-year-old daughter. She lost her restaurant job when the pandemic struck and her former employer argued that this meant she did not qualify for furlough. During the pandemic she relied on food aid from a mutual aid network, the Red Cross, and DISA Trinitat, and a spending card from social services to purchase food.[12] She spoke to Human Rights Watch while collecting a food delivery at DISA Trinitat, which she took to her new home in another part of the city after she and her daughter were evicted from their apartment in Porta:

The period of the pandemic was really a trauma for me. Sometimes I didn’t have money so would have to ask for help and food from friends. I had a three- or four-month phase of depression when I couldn’t even wash a plate, get up off the sofa. I went hungry during the pandemic, but my daughter never did. You know if you have a child, you can go for two or three days without eating so your child can eat. You’ll make whatever excuse you need to. Whatever we had—if it was macaroni or something else—was for her. I made do with a coffee or a glass of milk.[13]

Benito Balido Gomez, 63, a Filipino man, lives in Barcelona with his 56-year-old Ecuadorean partner, and their 13-year-old son, who is a Spanish citizen. He said he had worked as a cook, waiter, and eventually head chef, until he suffered three heart attacks and had had to stop working prior to the pandemic. He said, after receiving his family’s fortnightly food package at the Indian Cultural Centre in Sant Antoni:

SEPE (the state employment agency) gives me €450 each month in disability benefit. My wife still works at occasional jobs as a cleaner. Our mortgage each month is €720, we have to pay €75 for our son’s school [school-related expenses], water and electric end up about €60-70, my medication costs €60. I worked for 25 years in Madrid and Barcelona in well-known restaurants, always paying into social security. We’ve used up all our savings, sold our jewelry. […] What hurts me the most, is that by profession I’m a cook. And I can’t go back to cooking for work because of my health. And I’m here asking for food. It makes me resentful. I’m just asking for what’s mine. For now, we manage, we eat less. My wife is very stressed. If she gets sick and stops earning, we’re finished.[14]

Older People Reliant on State Pensions

The Covid-19 pandemic and the business closures that followed also put into stark relief the already precarious economic situation experienced by older people living on state pensions.

Spain’s state pension is a key part of the social security architecture and includes an age-related retirement pension, alongside other social security payments relating to disability, survivor (widow/er), and orphan status. Employees and employers pay into a contributory state pension scheme, generally available to people when they turn 65. At the end of 2020, there were approximately 6 million people claiming age-related pensions in total, and 8.9 million pension recipients, when other categories were included.[15]

People who have not paid in for the minimum of 15 years that the contributory scheme requires can apply for a non-contributory pension which had a base rate set by law in 2021 of €5,639 per year; and during the year 2021 also provided for a one-off additional payment of €525 to older people receiving the support who could demonstrate hardship and satisfy housing-related eligibility criteria.[16] However, according to some calculations, the actual annual amount received during the year could range between €1,409 as a minimum pension (with a lower than base rate allowance for older people who cohabit with another pension recipient, or with other family members whose earnings reduce their pension eligibility calculation), to €8,458 for a person with work-related disability or severe injury.[17]

The level of pension support through the non-contributory scheme falls short of what is needed for an adequate standard of living. In 2021, whether one used the lower Oxfam-calculated poverty threshold of €5,840 per year (€16/day), or the AROPE-based calculation provided by the official National Institute of Statistics and EAPN Spain of €9,626 per year, the base rate of the non-contributory pension (€4,833) fell below adequate levels.[18]

As recently as 2018, the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights criticized the inadequacy of Spain’s contributory and non-contributory age-related pensions, as insufficient to guarantee pensioners and their dependents an adequate standard of living, and called on the Spanish government to re-establish a clear index between social security benefits and the cost of living.[19] As pandemic restrictions waned, in May 2021, pensioners took to the streets across Spain, demanding “dignified pensions” that would protect their rights and permit them an adequate standard of living.[20] Pensioners’ associations have raised concerns that the existing levels of pension support is insufficient to maintain a dignified standard of living, as a result of more than a decade of sub-inflation increases, and what they considered an ongoing decrease value of their pension in real terms.[21]

In a positive step, the government passed legislation, which came into force on January 1, 2022, raising pension rates and ensuring that they are linked to the consumer price index, so they keep pace with inflation, which at this writing is 8.7 percent across the board (and 11 percent for food, and 17.5 percent for housing, including utilities).[22]

María, 71, is a Spanish citizen who lives with her 85-year-old sister, who is an Ecuadorean citizen, and who María did not think was eligible for any public support. When she spoke to Human Rights Watch in June 2021, María had been waiting in line for three hours at a food distribution point in the Sant Antoni district of Barcelona. She had been coming regularly for six months following a referral by the city’s social services department. She said:

My (age-related) pension is €600. The rent for the room my sister and I share is €400. I worked for 23 years as a cleaner and paid social security. The pension I get after working is not enough. All I ask for is a bit more, so I don’t have to wait here and beg for food. I’m not even asking for a dignified existence, just enough so I don’t have to beg for alms.[23]

Fernando, 73, is a Spanish citizen who moved to Madrid in 1963 and says he worked until he retired at the age of 65. He lives alone in an apartment a friend lets him live in. He spoke to Human Rights Watch while waiting for food at the Caritas distribution in San Ramón Nonato Parish in Puente de Vallecas, Madrid, where he had been getting food regularly for six months.

I receive (age-related) pension. It’s €395 [per month]. It’s very little. You can’t afford a life or pay the bills. The non-contributory pension is a pittance. What you need to understand is that this line we’re standing in is not a line of hunger, it is a line of need. People are here because they need help, they need support, they are not just here for food.[24]

Families with Children

Frontline organizations providing support to people in need, and anti-poverty analysts, have documented how families with children have been disproportionately impacted by loss of income, or reduced income while on furlough, during the pandemic.[25] Children’s rights groups raised concerns about the unequal impact during a prolonged period of school closures and total confinement of children at home for six weeks during 2020.[26] Low-income families struggled to make ends meet during this time, as the additional costs of keeping children fed rose. Survey research by Spain’s main single parents’ advocacy group, FAMS, has highlighted the disproportionate impact on single parent households, of which an estimated 82 percent are women-led.[27] In a survey of 545 single-parent households across Spain (of which 542 were women-led) conducted during the initial state of alarm, within the first month of closures, 27 percent said they could not afford the additional food costs, and another 34 percent said they had managed so far but were not certain they could do so if the situation continued.[28]

The official data confirm this worrying picture. The latest available national cost-of-living survey, from July 2021, is clear that while 26.4 percent of all households were at risk of poverty and social exclusion, the disaggregated data showed that 49.1 percent of single parent households were, and 37.8 percent of all households with more than two children also were.[29]

Spain and its autonomous communities operate a complicated system of allowances and benefits for families with children, some on the basis of disability, family size (single-parent households and households with three or more children), or means-testing, and others universally available, for example a monthly additional tax allowance for working mothers with children under the age of three.[30]

The inadequacy of Spain’s social assistance and social transfers to households with children has been the subject of significant international criticism in recent years. In 2019, the European Commission highlighted in a recommendation to the European Council that the “capacity of social transfers other than pensions [in Spain] to reduce poverty remains among the lowest in the Union, especially for children,” and that “[s]ocial spending as a share of GDP in Spain for households with children in Spain is one of the lowest in the EU and is poorly targeted”.[31]

A 2020 IMF-commissioned study documented that Spain has the highest child poverty rate in Western Europe (22.1 percent in April 2017), partly due to weak and inadequate coverage of its income support schemes.[32] The limited available evidence suggests that the introduction of the IMV, precipitated as a pandemic response but already part of the coalition government’s agenda, is not reducing child poverty, notwithstanding the Inclusion and Social Security Minister’s statement that it is “the best instrument to tackle poverty,” and in fact has been insufficient to mitigate growing child poverty during the pandemic.[33] Spain’s high commissioner for child poverty testified before parliamentary committee in October 2021, that although IMV was an important paradigm shift, Spanish welfare support was not reaching many families living in poverty, because the support provided was in itself insufficient, the eligibility thresholds were too restrictive, and because many families did not know they are entitled to such support and do not apply.[34] In a reply to Human Rights Watch, the Ministry confirmed that it aware of the problem of low take-up by potential beneficiaries, and considered addressing this a priority.[35]

Kréta Adamova, 29, a Czech Roma woman, who has lived in Barcelona since she was 4, lives in affordable social housing in the Verdum neighborhood, with her 8-year-old and 9-month-old daughters, and her 63-year-old mother. She worked in a slaughterhouse until she experienced a workplace injury three years ago. She said:

It’s hard to admit but we’ve gone hungry during the pandemic. From the food bank you get non-perishable foods, but the kids can’t just eat rice, lentils and beans. If we had money, we might buy chicken or meat for her (the older child) but not us (the adults). I would like my daughter to eat well. We’re now getting fruit and vegetable from the neighborhood food aid network. We can’t afford fruit at all. We make one dish and eat it across two meals in the day, and make one sponge cake (bizcocho) using leftover or expired yogurt to last for breakfast for three or four days.[36]

Veronica, 37, also lives in the Verdum neighborhood with her three children, aged 18, 14, and 12, and her husband, 34. All are Spanish citizens. Her husband was self-employed and worked in construction before the pandemic, and she earned money working in the informal economy as a cleaner. They live in social housing. She said:

We’ve been in debt to the bank since April 2020. We’re managing, we’ve pawned our TV, one of our mobile phones, and a video game console, to buy food. Thankfully my social worker now gives us €320 each month to pay for food and hygiene items at the supermarket. But we’ve had to come up with tricks at home to manage. We’re five people. I make four portions and tell the children I’ve eaten already. And I have a glass of milk for dinner. The strange thing is as a mother sometimes this comforts you. You get used to it. But look at my skin, I have vitiligo [an autoimmune skin disease which causes depigmentation], it’s a sign of stress. And I’m less patient, and I get anxious, when the kids ask me for things.[37]

Joan, 44, a Spanish man born and raised in Raval, continues to live there with his wife and their 10-year-old son. He was not eligible for ERTE furlough support given he worked in the informal sector, but was receiving unemployment benefits. After they received their fortnightly food package from a distribution center at the Church of Saint Augustine, Joan said:

I was working as a builder, always cash-in-hand, but there’s no work now. I’m unemployed and have been coming to the food bank for eight months. I get unemployment benefit (paro) but not minimum vital income. We’re managing, but look at us, we’re here, we’re at our limit.[38]

Many families living on low incomes in Spanish cities share apartments, often without formal leases, due to longstanding problems of insufficient social housing and unaffordable private sector housing.[39] Spain has among the lowest rates of social housing stock in the EU.[40] Families interviewed living in these circumstances reported having to choose between eating and paying their share of the rent, particularly during the initial near-total lockdown between March and May 2020. Migrant families with uncertain immigration status, and limited or no access to social security support, are more likely to live in shared housing.

Undocumented Migrants and Asylum-Seekers

Human Rights Watch research indicates that the rights of undocumented migrants and asylum seekers have been disproportionately affected by the flawed state response to the economic downturn. Migrants are more likely to earn at least part of their salary informally, thereby receiving lower or no furlough payments, or to be working in the informal sector, or to lose jobs in sectors impacted by the period of closures and public health protection measures, such as domestic care, and subsequent economic downturn.[41]

Migrants working in the informal economy, those without papers, and people seeking asylum reported difficulties accessing social security and even in some cases food banks because of a lack of the documents needed to establish eligibility. People without legal immigration status are only allowed basic, emergency social assistance, which is usually short-term or one-off in nature. People seeking asylum are in theory entitled to basic levels of social welfare support to ensure minimal conditions of dignity, but these require the person to make further applications beyond their initial request for protection. These problems were exacerbated by the closure of administrative offices that provide documents to migrants and asylum seekers for part of 2020 increased existing backlogs.[42]

Silvia Sánchez Bonilla is a Colombian woman who arrived in Spain with her husband, David, in August 2019. Both sought asylum and were awaiting formal registration of their asylum claims when interviewed by Human Rights Watch in June 2021. Silvia formed the collective, Carers Without Papers, which was running an informal food bank for others in a similarly precarious situation, who rely on occasional work in the informal economy for income. She showed Human Rights Watch the accommodation she and her husband were sharing, in the technical booth and storeroom of a theater which had given them shelter.

I can’t describe the feeling of not being sure what we’re going to eat the next day. By luck, we have had good neighbors and people who have helped us with food and somewhere to sleep. Equally, when we find some food and someone else needs help, we share it. We’ve been living on scrambled eggs and rice. We can’t cook where we are living now until nighttime, because there are people working upstairs.[43]

About a week after they were interviewed, the couple received their asylum registration cards, which gave them legal authorization to work in Spain until there is a decision on their asylum case.

Gloria Díaz, 39, also from Colombia, sought asylum in Madrid with her then 16-year-old daughter in February 2020. They were stranded and left without money in Barcelona when asylum processing was suspended during the pandemic. They restarted their asylum requests in June 2020 once immigration offices reopened. Her daughter became pregnant during the pandemic while they were living in a room in a shared apartment in greater Barcelona. She said:

When we lived in the shared apartment, we had to pay our way. We had no food, so when I could, I would try and cook for everyone with what they had, so my daughter and I could eat. My daughter was very sick, vomiting, right through her pregnancy and lost a lot of weight.[44]

Since late May 2021, the government has provided Gloria, her daughter, and newborn granddaughter accommodation in a town about 30 kilometers outside Barcelona and access to an online system which covers the costs of basic foodstuffs. Gloria said a month later:

Of course, we continue to economize and ration our food. My daughter is not vomiting anymore but hasn’t regained her weight. She’s having problems lactating. But at least we’re living together, we shouldn’t complain.[45]

Miguel, 32, and Jennifer, 27, from El Salvador, spoke to Human Rights Watch while collecting food distributed by the Indian Cultural Centre in Barcelona, where they were referred by the city’s social services for food aid. They and their 4-year-old daughter have lived in Barcelona since 2019 without regular immigration status after having been refused asylum in another EU country. Miguel said:

We live in a shared apartment, us three in one room. I earn about €600 each month as a construction worker. We spend €400 on our room and €80 on school fees. I have to pay my metro fare to get to work. We just about get by for food each month. We often go for one week every month where my wife and I don’t eat so our daughter can. We have to bear this. We’re the parents. If we didn’t receive this food aid, we wouldn’t reach the end of the month. At least we have milk and some food to give our daughter. I don’t know what we’d do without it.[46]

Yanay is a 37-year-old Peruvian single mother, without regular immigration status or fixed employment, who arrived in Spain in 2019. At the time of interview, she was living with her 18-year-old son and 14-year-old daughter in a room in a shared apartment in the Puente de Vallecas district of Madrid. She spoke to Human Rights Watch while standing in line waiting for food distribution organized by Caritas Madrid from the San Ramón Nonato Parish in the San Diego neighborhood of Puente de Vallecas:

We’ve gone hungry. We’ve had to cut back on a lot of things. There is no meat. We share fruit. The only milk we get is from the food bank. I work on the black market as a cleaner covering a friend’s shift on some days to pay my children’s school expenses. We wake up every day in the hope things will improve, but I wake up crying. This is the effect of not eating and not knowing what will come. The children know, they realize what is happening, and it affects their studies.[47]

II. Growing Reliance on Food Aid

As poverty suddenly grew and people’s need for urgent food aid was evident, national charities, civil society groups, and community organizations stepped in to fill the gap.

National food bank networks, which receive and distribute EU-funded food aid (Fund for Aid to the Most Deprived, FEAD) via the Spanish and autonomous community governments, and a wide variety of community-based associations and neighborhood groups mobilized food distribution to people unable to afford or access adequate food, including people who had been referred to them by social services agencies.[48]

National Food Bank Networks

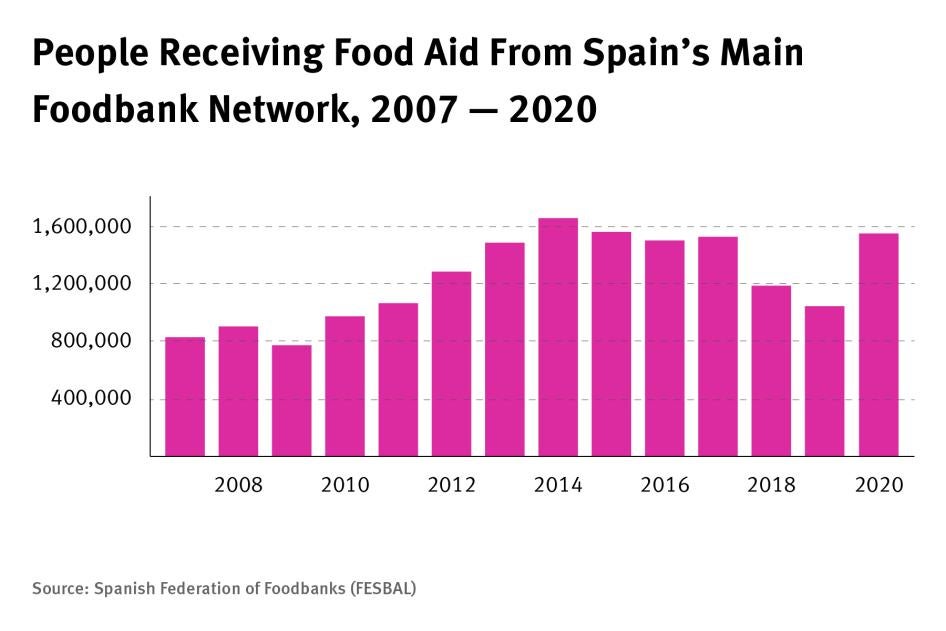

Demand for food aid has surged since early 2020. The Spanish Federation for Food Banks (FESBAL), which coordinates the country’s largest food banks and ensures delivery of governmental food aid with FEAD support, reported a marked increase in demand during 2020.[49] Interviewed in November 2020, Ángel Franco, FESBAL’s spokesperson, estimated that FESBAL had doubled the quantity it distributed from the spring to the summer of 2020.[50] By June 2021, FESBAL estimated its assistance had reached 1.56 million people including more than 300,000 children during 2020, almost up 50 percent in terms of total people reached compared to 2019. Figures from FESBAL member organizations in Madrid and Barcelona, interviewed by Human Rights Watch, were consistent with national trends.[51]

All three representatives of the national food bank network expressed shock at how quickly demand increased, and compared it to their experience during the global financial crisis and the subsequent Great Recession of 2008-10, which led to a housing and poverty crisis in Spain that continued after the recession formally ended in 2014.[52]

Gema Escrivá, Director General of the Madrid Food Bank told Human Rights Watch in November 2020:

We’ve already seen an enormous spike in demand. In three months of the pandemic, we were back at the levels of 2016; in the past financial crisis it took us from 2009 until 2016 to hit a peak. The crisis has been brutal in its velocity. And we’re still only in the calm before the storm really hits when the ERTE [furlough scheme] ends.[53]

Figure 1: Estimated number of people receiving food aid through FESBAL distribution, by year (2007-2020), compiled from FESBAL public documents[54]

Caritas, a Catholic relief and social service organization, also reported that by April 2020, it was assisting twice as many households in Barcelona Diocese with food and financial support as it had done the previous April and noted that it was seeing three times as many first-time visitors compared to before the pandemic.[55]

Human Rights Watch also sought information in writing from the central government and relevant authorities at autonomous community level on national and regional food bank use. At the time of writing, only Catalonia’s Department for Social Rights had provided this information.

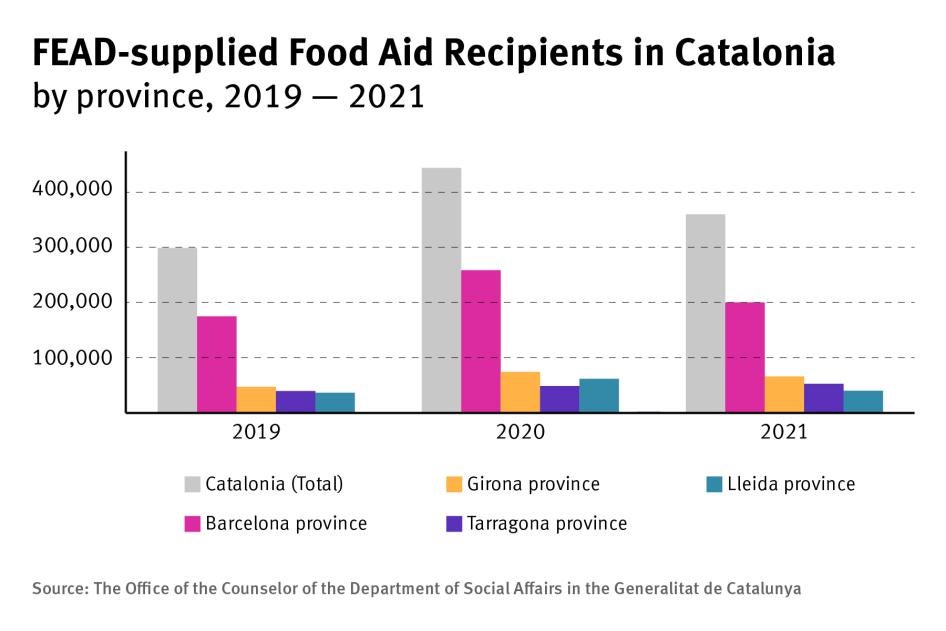

The data in Catalonia showed a 48 percent increase between 2019 and 2020 in the number of people collecting food aid distributed using the EU’s FEAD resources through Catalonia’s FESBAL affiliates and Red Cross chapters. Across Catalonia, despite a decrease in food aid distribution during 2021 from the 2020 peak, there were 60,524 more people receiving such food aid in 2021 compared to 2019 (an increase of 20 percent). The figure below shows how many people receiving FEAD-supplied food aid by Catalan province, and the total number at autonomous community level.

Figure 2: Number of people receiving FEAD-supplied food aid in Catalonia, disaggregated by province. These figures for each province are composites of the number of people assisted by the FESBAL affiliated food banks and the relevant Red Cross chapters.[56]

Neighborhood and Community Organizations

As need increased from March 2020 onwards, neighborhood and community groups, often building on existing links with housing rights activist networks developed during the 2008-10 financial crisis and migrant community organizations, began to coordinate mutual aid support networks, which included collecting and distributing food, or to significantly increase their existing efforts.[57]

Madrid

In Madrid, especially in lower-income neighborhoods, grassroots groups rallied quickly to deal with the demand, based on their existing activism and community links. In Vallecas, a largely working-class neighborhood to the south of Madrid’s city centre, a group of activists described how the collective Somos Tribu VK emerged to deal with the increasing need. Marimar, a social worker, said:

This was a social crisis that came out of a public health crisis. We started with a WhatsApp group. As a social worker and community educator you know what is coming. People in this neighborhood live at their limits. When the state of alarm came, there was an immediate need for food. People who made a living collecting scrap metal, or street-vending, or selling in informal open-air markets, suddenly had nothing—in some parts of Vallecas we would guess that’s a third of the population.

César Bárcenas, coordinator of one of the Somos Tribu VK neighborhood pantries, in San Diego, added:

It’s just how our neighborhood works. It’s a neighborhood of solidarity. People now come in and donate food and say we got through it with your help, now it’s our turn to help you.[58]

In the Lavapiés neighborhood of central Madrid, another low-income area, Asociación Valiente Bangla, an organization of Bangladeshi migrants in Madrid advocating for their rights, organized food collection and distribution from late March through the end of June 2020, initially for Bangladeshi migrants, but eventually to about 450 households including migrants from various countries and non-migrants. Asociación Valiente Bangla is part of a wider network of groups coordinating food distribution in Lavapiés, including AISE, a Senegalese migrants’ association; Dragones Lavapiés, a youth football club; and BAB-Colectivo and Hola Vecinas, both neighborhood associations.[59]

Mohammed Fazle Elahi, from the Asociación Valiente Bangla, said:

Many of the Banglas [Bangladeshis] here are undocumented, they don’t have papers. So there is no aid from the state, the regional government, the city’s social services. These are people who work in restaurants cooking and cleaning, in internet and phone shops, in greengrocers, working 15 hours a day on contracts that say they work 4 hours. It’s not just Banglas, also Africans, Moroccans, Latin Americans, Indians, Pakistanis. What we need is to live in dignity, to work in dignity and pay our taxes. We need regularization. If our work and immigration situation was more regular, we would have better access to the unemployment support.[60]

Barcelona

In Barcelona, grassroots neighborhood associations, formal and informal trade union organizations, food distribution centers run by churches, and cultural organizations, such as DISA Trinitat (part of a group of Caritas-linked neighborhood pantries, see further description below) and the Indian Cultural Center, reported a similar sudden spike in people needing food aid.[61] Marta Marzal, coordinator of the food distribution at the Indian Cultural Centre told Human Rights Watch in June 2021:

We’re a cultural organization. We used to have dances and festivals and donate to food banks sometimes. We didn’t distribute food. Suddenly the pandemic and state of alarm came, and we saw a need to help people. Some people earned 20 to 40 euros day to day, and were stuck at home with no money. We began on March 25 or 26, 2020, and by the second day there were 100 people. By mid-April there were 600. We are now seeing 350 families, which is about 720-750 beneficiaries, every fifteen days. We used to give food to anyone who came and said they needed it, but we now coordinate with Social Services, so everyone who now queues is supposed to be referred to us by Social Services. And we’ve had to say to Social Services, we can’t take more, we don’t have the food. But still people come because they can’t get a Social Services appointment, the city council’s offices are overwhelmed. Who helps these people? The administration doesn’t even know they exist.[62]

The People’s Union of Street Vendors in Barcelona, who are primarily from West African countries, organized food collection and distribution during the first months of the pandemic, after the pandemic meant their members (referred to colloquially as manteros in Spanish and manters in Catalan, owing to the practice of vending their goods displayed on a blanket or manta) were unable to work. The Union worked together with the Barcelona Food Bank, Barcelona’s main wholesale food market, and individuals who donated food or cash, to ensure street vendors and others who contacted them for help did not go hungry.[63]

Papalaye Seck, a member of the street-vendors’ union said:

Street-vending was prohibited before the pandemic too. Many, most of the manteros don’t have regular migration status, it’s the only way to survive. The pandemic came, and there were fines for going out. The manteros couldn’t sell anything. It’s easy for police to stop us because we’re Black. Whatever manteros were earning before became zero. Most manteros don’t have savings, bank accounts, no ERTE. We knew many manteros were already poor and suffering, but the pandemic made it obvious.

People who live and work in the hidden economy can survive in normal times, but when a crisis comes and the formal economy stops, so does the hidden economy. We need these people to be included in the support. The government announce a minimum vital income and say they won’t leave anyone behind. But what about the undocumented people who aren’t even allowed to ask for it? It leaves thousands and thousands behind. What we need is a regularization policy to allow migrants to work, pay social security and taxes, and get the support.[64]

Church-linked Food Distribution

In addition to the long-standing tradition of churches distributing “alms,” which multiplied with queues extending outside churches for weekly or fortnightly food distribution, Caritas Spain, the relief and social service organization linked to the Catholic church, and its local volunteers began developing new ways of dealing with the rising need for food aid. Part of this was an effort to move away from the classic “handout” model towards a model that would assist families and individuals to overcome broader challenges including the stigma of queuing for food, and address some of the underlying structural factors driving people to need food aid.

DISA Trinitat in Nou Barris, Barcelona

DISA Trinitat is a volunteer-run social project and pantry backed by nine local parishes and Caritas of Barcelona Diocese, with help from Barcelona city council and the local government and social services in the Nou Barris district. It has provided direct aid to people in poverty since 2012.[65] To receive assistance from DISA Trinitat, people need to be referred either by the city’s social services or by Caritas. Seventy percent of the food it distributed comes from the Banc d’Aliments de Barcelona and FEAD-backed food distribution programs, and the remainder from Caritas, local church donations, supermarkets, philanthropic foundations, and private individuals.

Antoni Quintana, who coordinates DISA Trinitat, described the project as initially being one based on creating an environment in which people experiencing poverty could receive assistance and have volunteers work through other concerns they may have (for example, mental health, employment, medical care), and not just hand out food. Quintana told Human Rights Watch that they adapted their model during the pandemic:

Other DISAs and social projects closed when the pandemic came. But we felt an obligation to stay open, despite the risks to us, or rather, knowing the risks to us. […] There’s been a huge rise in people coming since the pandemic. The majority of new visitors are families with children. They say single-parent families, but let’s say it like it is. They are single-mother families, mothers with children.

After all this we now need to work out how we return to a model that is more focused on human dignity, that recovers the human part of what we should be doing, accompanying them in their lives so they don’t need to come back.[66]

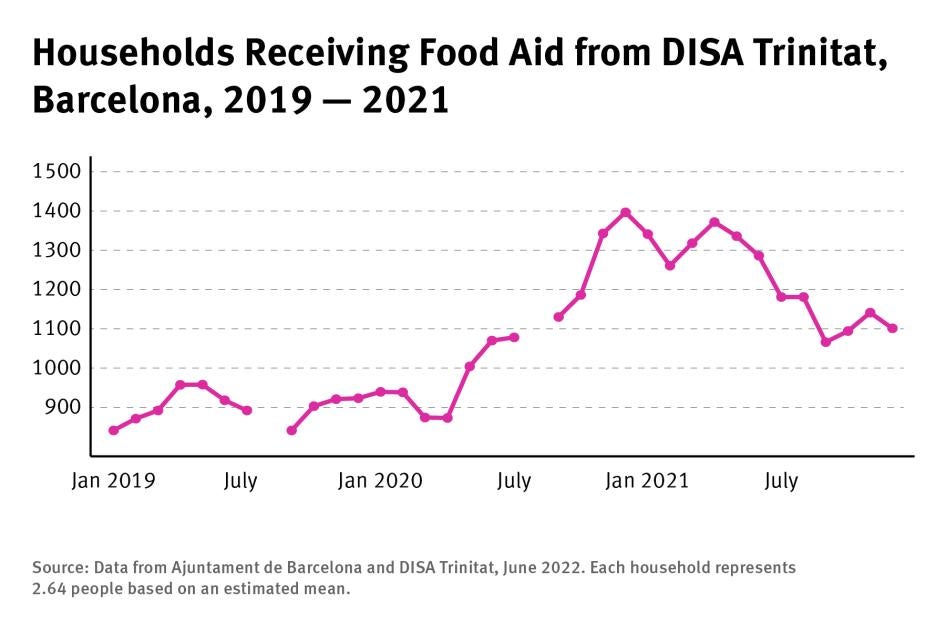

Data from DISA Trinitat bear out broader trends observed by the FESBAL member food banks and Caritas for people attending food distribution in the first year after the pandemic hit Spain, with a reduced number of households seeking food aid over the course of 2021, but remaining notably higher than pre-pandemic levels. The data from DISA Trinitat are also consistent with the broader pattern documented by the Catalan regional government’s data on FEAD-provided food aid across the four provinces of Catalonia.

Figure 3: Data from Ajuntament de Barcelona and DISA Trinitat, June 2022. Each household represents 2.64 people based on an estimated mean.[67]

Quintana described the role of the DISA Trinitat volunteers in relation to the responsibilities the state has to its citizens and residents, saying:

With the taxes we all pay, the state should be able to take care of more people, in dignity, decently. But if we weren’t here, it would be chaos, people would be living on the street. It feels like we’re the firefighters of social justice, we keep putting out fires with the food distribution. But the social injustice continues.[68]

The Caritas Economato Solidario in Puente de Vallecas, Madrid

Human Rights Watch also visited and spoke with staff, volunteers, and service users at a similar Caritas-backed social supermarket (economato solidario) scheme based in the parish church of San Cosme and San Damián in Vallecas, Madrid.[69] The project had been running as a pilot project for a year, backed by Caritas Madrid’s Fourth Parish.

People were referred to the social supermarket by the city’s social services, by Caritas, or by other neighborhood organizations. Once referred, they could visit on days the social supermarket was open, and exchange the “points” they had been allocated based on their family size for their choice of non-perishable foods and cleaning and hygiene supplies. When interviewed in January 2022, a representative of the local Caritas parish said the social supermarket planned to introduce a separate voucher program, operated in coordination with a local market, where service users could exchange points for fresh fruit, vegetables, and meat.[70]

III. State Response Failing to Meet Needs

Poverty rose in Spain during the pandemic, as it did in other countries in Europe.[71] Official European Commission data from Eurostat showed that although across the EU, median disposable incomes and “at risk of poverty and social exclusion” (AROPE) rates remain stable, the AROPE rate rose in nine EU countries, of which Spain was one.[72] A World Bank commissioned study found in August 2021 that between 3.6 and 5.4 million more people across Europe were at risk of poverty or social exclusion compared to before the pandemic, noting that the “economic fallout could have been much worse absent the sizeable government support.”[73] The study also noted the disproportionate impact on Southern European countries which have 36 percent of the 27 EU countries’ population but accounted for more than half total increase in poverty, and projected that by 2022 “at risk of poverty” rates in Southern European countries would have returned to their 2013 peak, following the global financial crisis.[74]

A key NGO report by the European Anti-Poverty Network Spain (EAPN-ES) estimated that some 4.5 million people across the country were living in severe poverty (on less than €6,417 per year) in 2020.[75] EAPN-ES estimated that 620,000 more people were at risk of poverty in Spain in 2020 than in 2019, representing the first increase in this rate since the peak of the effect of the global financial crisis in Spain in 2013/14.[76] Oxfam Intermón has calculated, using official data, that during 2020, people in the lowest two income deciles in Spain saw their disposable income fall 15.8 and 9.7 percent, on average, respectively, compared with a 3.7 percent average decrease in all other income groups.[77] Official figures based on the annual cost-of-living survey published in 2021 showed that the percentage of the population experiencing “severe material deprivation,” rose from 4.7 percent in 2019 to 7 percent in 2020.[78]

Perhaps the most visible symbol of the material deprivation was the growth in lines of people queuing to receive food. This was linked to the increase in the number of people at risk of poverty, alongside the sharp drop in income for so many already in the lowest income brackets.

The government response to the economic impact of the pandemic was hampered by existing failures in social security and social assistance systems, including the inadequacy of levels of financial support, a difficult to navigate social security bureaucracy, and delays in social security application processing and payments. New efforts at the national level to address the situation—a pandemic-related furlough program and ban on layoffs to protect workers—together with a newly introduced but previously planned minimum national income (IMV) program helped, but were insufficient to meet additional needs, especially the IMV which in practice benefitted only a fraction of its intended beneficiaries.

A Pre-Pandemic Social Protection System Doing a “Poor Job” Tackling Poverty

In February 2020, the then-UN Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights, Philip Alston, concluded a trip to the country, assessing that it had a “completely inadequate social protection system that leaves large numbers of people in poverty by design.”[79] Alston assessed Spain’s social protection system as doing a “poor job of tackling poverty,” remarking that “when support does reach people, the amount can be extremely low.”[80]

The government’s response to the pandemic, in part, sought to address existing criticisms of the system, but fell short of what was needed to ensure protection of people’s rights to food and to an adequate standard of living.

Pandemic Employment Protections: Furloughs and Bans on Layoffs

To protect workers and prevent massive unemployment, like other countries, the Spanish government responded to the imminent economic crisis with a furlough scheme. In Spain, this covered 70 percent of the wages of employees and workers unable to work due to the pandemic, and a temporary ban on employers using the pandemic as a justification for layoffs.[81]

Announced in March 2020, the pandemic-related furloughs (referred to as ERTE, based on the Spanish acronym for an existing labor code provision for temporary work reduction extended for this purpose as an emergency measure) were initially scheduled to last only until the “state of alarm” ended in June 2020.[82] The ERTE scheme was extended successively, with some modifications, until it ended on March 31, 2022.[83] The number of people receiving ERTE plateaued at around 750,000 between September 2020 and March 2021, but had dropped by January 2022 to 105,000.[84]

The tax evading pay practice in which employers pay their staff part of their income officially with social security contributions and tax deductions, and the remainder unofficially in cash (often referred to as “in B”), created a problem for low-wage workers paid this way.[85] Although the exact extent of the practice is hard to pinpoint, most estimates indicate that approximately 20 percent of GDP is in the informal economy.[86] Fourteen percent of employers surveyed in 2021 admitted to paying some or all of their employees’ wages “in B.”[87] Women are more likely to be in jobs that are paid “in B” than men, and people under 24 are particularly susceptible to such exploitation given Spain’s high level of youth unemployment.[88]

Furlough payments only covered 70 percent of the officially registered salary and not the “in B” component. In July 2021, the government passed a legislative reform which banned payments in cash for products and services over €1,000, in an effort to curb tax evasion on cash transactions.[89] The effect of this reform is likely to have been minimal for people on low wages calculating furlough entitlement, because, as was illustrated by the experience of those Human Rights Watch interviewed, the “in B” portion of their monthly wage is almost certain to have been well below the €1,000 threshold.

Jessica Ferrer, a 36-year-old Italian woman of Venezuelan origin, who worked as a cook before the pandemic, and at the time of her interview was an active participant-organizer in a neighborhood pantry coordinated by Somos Tribu VK in Puente de Vallecas, Madrid, explained what this meant in practice. She said:

We are ordinary working people. I worked as a cook and earned €825 a month. €425 of that was official salary, and €400 was paid “in B”. So, when I got my ERTE eventually in November 2020, it was 70 percent of €425, not of €825, and ended up being about €300.[90]

Workers in the informal economy who suddenly had no income also, in most cases, had no recourse to the contribution-based social security system (since they had not paid into them) or to furlough payments (which were available only to those whose pay and jobs were registered officially on the tax and social security systems). Nor could workers in the informal economy, who were already outside regular formal employment, benefit from the ban on layoffs.

It is worth noting that the absence of the ERTE furlough scheme, would have been disastrous. ERTE support did reach people in the lowest income quintiles and was among the more efficient of the social security responses, but still fell short for key sectors of the population.[91]

Minimum Vital Income: An Important, but Flawed, Program

Faced with rising unemployment and projected poverty with the onset of the pandemic, Spain’s national government legislated in May 2020 for a national Minimum Vital Income (IMV, in Spanish) scheme, allowing applicants to claim between €461.50 and €1,015.30 per month based on household size and composition.[92] The IMV was, in theory, available to applicants retroactively from June 1, 2020, so long as they applied before the end of 2020.

The incumbent governing coalition had already planned to introduce the IMV prior to the pandemic, but accelerated its implementation as a pandemic response.[93] The national IMV scheme was developed in addition to existing social assistance schemes established by Spain’s regional governments or autonomous communities, of widely varying quality, levels of support, and reach.[94]

It is important to note that the IMV is not a universal basic income scheme, as its name may suggest, but rather a basic social assistance program that provides support based on several eligibility criteria.[95]

In June 2020, soon after the IMV was announced, Olivier de Schutter, the UN Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty, offered a cautious welcome to the national scheme, calling on authorities to widen coverage and eligibility to ensure people were not excluded by age and immigration status requirements.[96]

IMV has some arbitrary exclusions built into its design, which affect young adults in poverty and people without regular immigration status. It is available to people between the ages of 23 and 65, and to adults aged between 18 and 22 only if they are responsible for a child.[97] It requires applicants to document that they have lived independently for a minimum period of between one and three years, and requires all applicants to have one uninterrupted year of legal residence in Spain.

In practice, the IMV’s reach has been limited and its rollout slow and uneven across Spain’s regions, who are responsible for providing social protection. There is also some confusion about how IMV allowances correspond with regional social assistance, and how national and regional authorities reconcile any difference in accounting. An official in the Ministry of Inclusion, Social Security and Migrations clarified in writing to Human Rights Watch that IMV was designed as a “floor provision” that autonomous communities could “complement” or top up with their social assistance programs.[98]

An investigative analysis by the news outlet Diario 16 of public data on IMV coverage estimated that only 6.4 percent of the country’s population living below the poverty line were receiving the IMV by the end of March 2021, and that it varied between 3.5 and 16.8 percent depending on the region in which the application was made.[99] The same analysis showed that by the end of March 2021, nine months into the existence of the IMV scheme, three quarters of applicants had been refused support, for a variety of bureaucratic reasons including non-compliance with a complex application process, stringent documentary requirements (such as evidence of people living in the household and updated municipal registration certificates showing the members of the household or “unit of cohabitation”), or a flawed means-testing calculation (see below).[100] Further research during the year by NGOs working in this area corroborates the concerns about IMV’s extremely limited reach, although their estimates differed slightly. Oxfam Intermón estimated in June 2021 that 1.56 million people in severe poverty were left out of IMV’s reach owing to design flaws.[101] A survey by Caritas and social science researchers at the FOESSA Foundation found in October 2021 that—owing primarily to a lack of information about the program—only 26 percent of households living below the poverty threshold had successfully completed their IMV application; and of those only a fifth had been successful, and about half had been denied the support for the reasons noted by Diario 16 and Civio (below).[102]

More recent detailed analysis of official data by Civio, a public interest journalism and advocacy organization, has shown that 29.8 percent of refused applications were because the social security authorities considered the household or “unit of cohabitation” information to be inaccurate, and a further 18.8 percent for missing documents.[103] A professional association representing senior social services workers raised similar concerns in April 2022.[104] One organization that provides support (including food aid) to families with children and pregnant women in poverty, explained to Civio’s researchers that if a couple separated during the pandemic and one parent was left with the children, because municipal offices were closed or facing backlogs they did not update their registers.[105] Separately, Civio notes that Spanish administrative law does not require applicants to provide copies of documents that should already be in the possession of the authority concerned or other administrative authorities. As result, some of the refusals of IMV support for “missing documentation” may not have been in accordance with Spanish law.[106] Related research by Civio on high levels of success in appealing IMV refusals supports this assessment.[107]

People Human Rights Watch interviewed described that they had faced these reasons when refused IMV support.

Pedro Luis Álvarez Malberty, a 40-year-old Spanish citizen born in Cuba, who acquired Spanish nationality through descent in 2011 and migrated from Cuba to Spain in November 2020 with his wife and their two young daughters, aged 6 and 3. Their daughters have Spanish nationality, but Álvarez’s wife remains a Cuban national. Álvarez told Human Rights Watch, that after falling ill and needing surgery, he did not qualify for medical disability benefit because he had not satisfied the minimum contributory period for the type of illness he had. Pedro was not eligible for IMV because his wife’s Cuban nationality and related length of legal residence in Spain meant that the family of four did not satisfy the household (or “unit of cohabitation”) eligibility requirement of one year. He explained, sitting at home in Puente de Vallecas, Madrid, after having collected food from the nearby Caritas social supermarket:

Caritas and the neighborhood groups have given us food. Madrid city council has helped us with food from time to time. It isn’t a regular thing, but it happens occasionally and is a lot of paperwork which takes two or three months to arrive, but, yes, we’ve had help in the form of a Carrefour [supermarket] card, or a basket of food. But the other sorts of social welfare support, like minimum vital income—when we try to access it, we come up against limitations every time. For example, if you’re not registered as resident in Madrid for a whole year, you can’t access the minimum vital income. We’ve been here for 15 months, but because my wife forms part of the family unit, and she has only had legal residence for a few months, we’re not eligible… We always find ourselves in a limbo. What sort of limbo do I mean? There’s always some requirement that leaves us out. […] Every time we ask for a social security support of this kind, we end up coming up against a roadblock that doesn’t let us pass.[108]

Manuela, 38, a Spanish woman, used to earn €570 a month working as a cleaner for a subcontractor providing maintenance services at a sports stadium but lost her job when the pandemic curtailed clients’ operations. She said the cleaning subcontractor considered the seasonal contract under which she was employed to have ended when spectator sports could no longer take place, and told her she would not receive ERTE furlough support. She was refused IMV and explained that it was because the social security authorities continued to treat the father of her children, from whom they were estranged, as a family unit. She spoke to Human Rights Watch while waiting for a fortnightly food distribution at Somos Tribu VK’s Palomeras Bajas neighborhood pantry in the Puente de Vallecas district of Madrid. At the time of the interview, she had no income beyond limited child maintenance payments from her former partner, and said that she depended on what she received at the pantry to feed her four children, aged between 3 and 15. Manuela said:

You feel it as a mother. It hurts. I feel like I am failing them. I brought them into the world to give them a good life, and I feel like I’m worth nothing. We all have a right to a dignified life. So many of us are living in poverty, more so in the pandemic. The poor just get poorer.[109]

The success and reach of the IMV program has been limited by delays in providing accurate information to potential beneficiaries about how IMV works, and a bureaucratic system that was overwhelmed by demand. Early in the pandemic, the country’s social security system was overwhelmed generally with requests—beyond IMV applications—and did not have sufficient appointments available to deal with standard requests like people entering retirement receiving their pension, and struggled to catch up with new applications for IMV. The prolonged closure of social security offices, followed by a gradual re-opening with strict limits on numbers of appointments per day, as part of the public health protection measures contributed to the backlog.[110]

A design flaw in the IMV program and its underpinning assessment logic also affected its effectiveness in tackling poverty during its first year and a half of operation. A key factor in deciding whether a person in 2020 was eligible for and in need of assistance was their income the year before, in this case in 2019, prior to the pandemic. People who had reasonable incomes before the pandemic, and had not previously been experiencing poverty, often had their applications for the IMV refused as a result. Legislation passed in December 2021 has begun to correct this flaw, allowing people to claim the IMV based on income in the year that the person is applying, but at this writing it remains unclear to what extent earlier miscalculations on eligibility will be recalculated.[111] In response to a request from Human Rights Watch asking for an explanation of when IMV eligibility would be delinked from earnings in the previous fiscal year, and what recourse people denied their IMV application on this basis, the Ministry for Inclusion, Social Security and Migrations simply stated that the modifications and reforms are in force, and offered no clarification on how past mistakes would be rectified.[112]

Anti-poverty campaigners have also criticized the IMV program’s level of support as not being adequate to meet the financial need of families with children generally, and single-parent families in particular.[113] In December 2021, Parliament approved amendments to the benefit levels for families and people with disabilities, including increasing child-related benefit payments under the IMV scheme by between €50 and €100 per month per child, depending on age.[114]

Following increases to levels of social security support effective January 2022, the IMV benefit ranges from between €491.63 for a single adult per month to €1081.59 for a household with two adults and three or more children, or one adult and four or more children.[115] The IMV also now includes modest additional supplements for single-parent families and households in which one of the residents has disability status certified by the state, in response to the concerns raised about the adequacy of earlier levels of IMV support to meet the needs of people in such households.