The UK government says it wants to end modern slavery. But if that’s true, why has it been stalling on a key reform which would help protect migrant domestic workers from abuse at the hands of their employers?

The need for reform is urgent. Because their work is behind closed doors, domestic workers are among the most vulnerable in the world. Human Rights Watch has documented severe abuse among these workers in the UK, including the confiscation of passports, physical and psychological abuse, deprivation of food, and little or no wages. In some cases the abuses amounted to forced labour.

Until now, the British government has refused to carry out the one key reform which could help stem this abuse: ending its tied visa for migrant domestic workers.

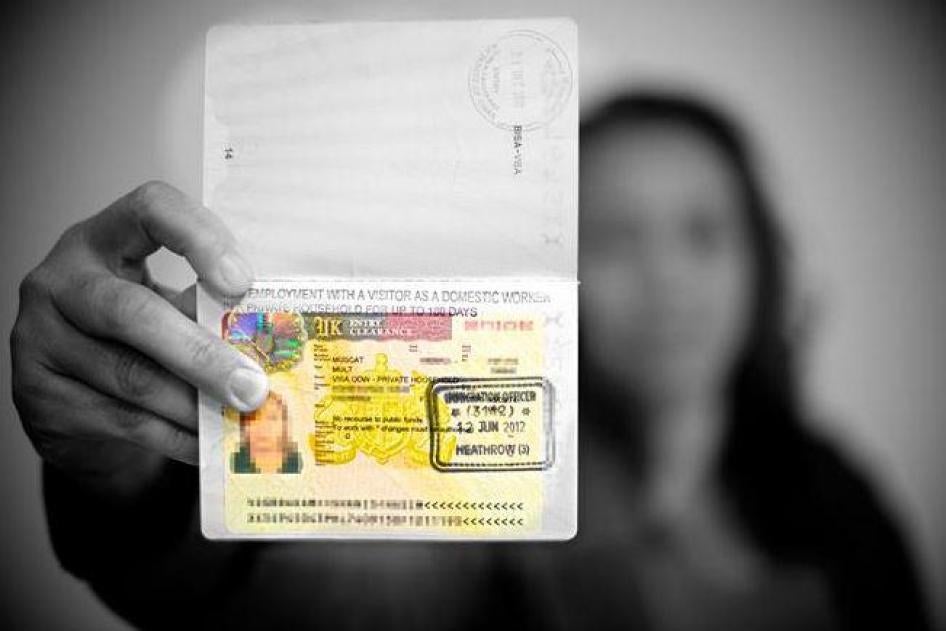

The UK’s tied visa system was introduced by the government in April 2012. It allows domestic workers to accompany their employer, often from one of the Gulf countries, to the UK for up to six months, but it gives workers no legal right to seek new employment once they are in the country. The visa legally binds a worker to an employer.

As a result a worker who is abused by her boss is faced with two choices: to stay and live with the abuse, or run away and risk deportation. This is a terrible ‘choice’, and leaves many trapped in horrific conditions.

But that could all be about to change. Last week, a report published following an independent review ordered by the government concluded that the UK should end its tied visa system for migrant domestic workers. The government should follow this recommendation without delay.

Human Rights Watch and others had presented the government with evidence that tying domestic workers to their employer facilitates their abuse. Two Parliamentary committees also made recommendations to end the tied visa.

Ending this abusive system does not require new legislation. The government can remove this stain on the UK’s reputation simply by abolishing the tied visa and thereby allowing migrant domestic workers to change employer, and work in private homes for up to two and a half years without needing to grant them a right to permanent residence in the UK. This should also apply to migrant domestic workers in diplomatic households, as the independent review rightly recommends.

Earlier this year Karen Bardley, the UK Minister for Preventing Abuse and Exploitation, said that “whoever is in government […] will implement the review’s recommendations.” That review has unequivocally called for the tied visa to be scrapped. All David Cameron’s government has to do now is keep its promise.