A 16-year-old Afghan boy, traveling alone, entered Hungary from Ukraine in April 2010. Hungary promptly sent him back to Ukraine, where border guards detained him. He described to me his interrogations there by men in civilian clothes:

One time they kicked me and one time they punched me. The second interview was about four days later... [He] brought electricity... it had two wires that came out of the end. They gave me four shocks. Three times on my ear lobes and one time on my neck... Before they did this to me they did it to my friend. I stood and watched and they shocked my friend five or six times.

In a few weeks Hungary takes over the EU presidency and with it the difficult task of moving forward the EU's negotiations on a common migration and asylum policy. But Hungary's own record may hamper its chances of leading an EU reform that fully respects the rights of migrants and asylum seekers.

Our findings in a recent Human Rights Watch report document how Hungarian police officials quickly sent migrants who had entered through Ukraine, including unaccompanied children, back there, even when they had tried to seek asylum in Hungary.

Many of those forced back told us they were ill-treated, or even tortured, while in custody of Ukraine's State Border Guard Service. The 16-year-old Afghan's experience is one of 12 accounts of ill-treatment or torture we heard from migrants Hungary had sent back there. He told me how he was deported from Hungary:

The Hungarian police came and asked for our documents. They took us to a police station and searched our pockets... I was caught on April 19, 2010. They sent me back the morning of April 20.... I gave them my age... they said they would help me, and then they deported me.

Under both EU and international human rights law, Hungary must not return people to a place where they risk inhuman treatment or torture, such as beatings or electric shocks. In Ukraine, that risk is real.

Further, Ukraine does not protect people who fear persecution in their own countries. Ukraine's asylum system is dysfunctional and Human Rights Watch was told, over and over again by interviewees, of how they were expected to pay bribes to have their claims move forward. The government has simply not shown itself capable of protecting vulnerable groups of migrants, including unaccompanied children. For example, we were able to find only two cases in which migrants from war-torn Somalia had been granted asylum and only one for an unaccompanied child.

Ukraine's ill treatment of migrants and failure to protect asylum seekers and children should not only concern Hungary, which has long returned irregular migrants to Ukraine under a bilateral agreement. Now other EU member states are working toward full implementation of an EU-wide readmission agreement with Ukraine that entered into force last January. Under this agreement, any EU state can send a migrant back to Ukraine if there is evidence the person has entered the union from there.

But based on what we know is happening to people sent back there, EU member states should not be planning more returns to Ukraine. Instead, EU countries should suspend the readmission agreement altogether until Ukraine demonstrates it can treat migrants in a dignified and humane manner in line with EU standards.

Hungary should be the first to do so, demonstrating by example that the absolute ban on refoulement - the return of a person to persecution, inhuman and degrading treatment, or torture-remains a core value for the EU.

Hungary has an important opportunity for leadership on this issue. It should demonstrate by revising its own policy that a common EU policy on migration and asylum does not need to come at the expense of the fundamental rights of migrants and refugees, or of the EU's respect for those rights.

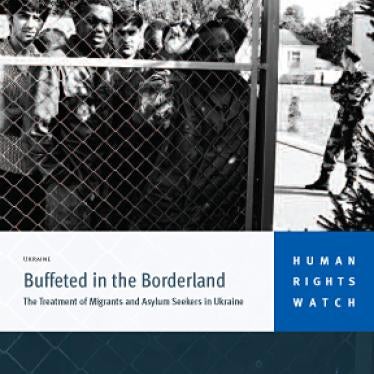

Simone Troller is a senior researcher with Human Rights Watch and co-author of "Buffeted in the Borderland: the Treatment of Migrants and Asylum Seekers in Ukraine."