Buffeted in the Borderland

The Treatment of Asylum Seekers and Migrants in Ukraine

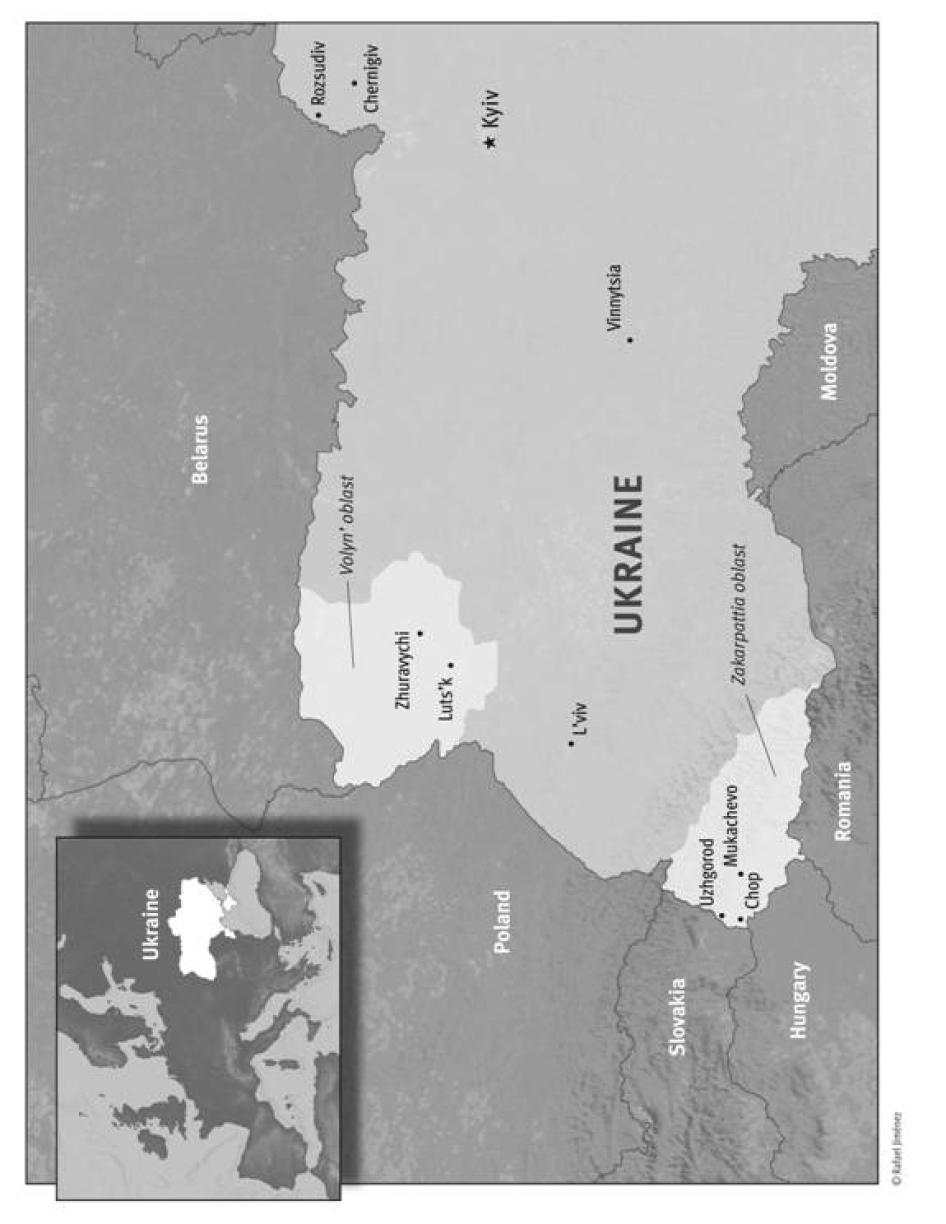

Map of Ukraine

I. Summary

When I said I wanted to seek asylum [the Slovakian border guards] said “yes” but took us back to the border [with Ukraine]…. The first night [after return] I spent in a border place. People there were hitting me. I asked for food. The border guards said “fuck you”…. They punched me on my heart … also on my mouth and my back. I fell on the ground and they hit me more.

A Pakistani asylum seeker recounted his treatment in Ukraine after he was deported from Slovakia on May 21, 2010.

On January 1, 2010, a readmission agreement between the European Union and Ukraine came into force that provides for the return of third-country nationals who enter the EU from Ukraine. Readmission agreements are a cornerstone of the European Union’s so-called externalization strategy for asylum and migration. The core of this strategy is to stop the flow of migrants and asylum seekers into the EU by shifting the burden and responsibility for migrants and refugees on those countries that neighbor the Union, in this case Ukraine. Such an agreement presumes, however, that the receiving state will provide comparable treatment and respect for rights as the sending state. That, as this report will show, is not the case.

Ukraine has a dysfunctional asylum system that was completely unable to recognize or provide protection to refugees from August 2009 through August 2010 and at the time of this writing is struggling to manage the backlog of claims that were not processed during that time. Not only has Ukraine been unable or unwilling to provide effective protection to refugees and asylum seekers, it has also subjected some migrants returned from neighboring EU countries to torture and other inhuman and degrading treatment.

The EU-Ukraine readmission agreement sets out a broad procedure for returns, including an accelerated procedure for individuals apprehended near the border. But human rights protections in the agreement are very thin, amounting to an overall savings clause stating that nothing in the agreement allows a party to violate their obligations under refugee or human rights law.

In the five years leading up to activation of the readmission agreement, and continuing afterwards, the EU has invested millions of Euros to build Ukraine’s capacity to stem the irregular arrival of migrants and asylum seekers into the EU. While these capacity-building funds have devoted some resources to asylum procedures and reception and integration of asylum seekers and refugees, such funding pales in comparison to the money the EU has poured into re-enforcing Ukrainian border controls and boosting its capacity to apprehend, detain, and deport irregular migrants. While Ukraine is engaged in building and renovating migrant detention centers, it appears unable or unwilling to adequately feed the migrants it currently detains and charges the detainees with the costs of their own detention and transportation between facilities.

Because the implementing protocols of the EU readmission agreement had not been finalized as of the writing of this report, nine months after the agreement formally went into effect, neighboring EU countries were operating informally on the basis of bilateral readmission agreements from the mid 1990s. According to those bilateral agreements, migrants entering Poland, Slovakia, and Hungary without permission can be summarily returned if caught within 48 hours of crossing.

Of 161 refugees, migrants, and asylum seekers interviewed in Ukraine, Slovakia, and Hungary, we received 50 testimonies of persons who said they had been returned from Slovakia or Hungary. Most of them said they had asked for asylum upon arrival in those countries, but that their pleas had been ignored and they had been swiftly expelled. These practices breach the right to seek asylum contained in the binding EU Charter of Fundamental Rights. Both Slovakia and Hungary also returned unaccompanied children to Ukraine in violation of their international obligations to protect them.

Neither Slovakia nor Hungary allows for independent monitoring of returns, and neither country provides for an effective remedy that would protect migrants against ill-treatment upon return. The launching of an appeal against a deportation from Slovakia or Hungary does not suspend the return. Returnees do not have access even to minimal information on arrest and return. In practice, Slovak and Hungarian border authorities often trick migrants into believing they will not be returned or coerce or deceive migrants into signing papers they do not understand, which are then used to send them to Ukraine.

The number of third country nationals believed to have crossed irregularly from Ukraine and apprehended in Slovakia and Hungary has been decreasing steadily since 2008, as has the number of asylum applications lodged. Slovakia apprehended 978 migrants entering the country from Ukraine in 2008, 563 in 2009, and 203 between January and June 30, 2010. The vast majority were deported to Ukraine: 691 in 2008, 425 in 2009, and 140 during the first six months of 2010. The remaining were not returned, including some who were admitted into the asylum procedure. Hungary deported 425 migrants to Ukraine in 2008, 284 in 2009, and 164 between January and August 31, 2010. At the same time, Hungary admitted 555 migrants who entered the country from Ukraine into the asylum procedure in 2008, 152 in 2009, and 21 up to August 31, 2010. The return of almost all third country nationals to Ukraine took place under an accelerated procedure.

More than half of the migrants interviewed by Human Rights Watch who had been returned from Slovakia and Hungary said that they were beaten or subjected to other physical mistreatment upon return to Ukraine. Some migrants and asylum seekers, including children, gave credible accounts of having been tortured during interrogations while in the custody of Ukraine’s State Border Guard Service (SBGS). Allegations included accounts of being subjected to electric shock by Ukrainian plain clothes officials during interrogations about smuggling networks. An Iraqi man spoke of his interrogation after being arrested by Ukrainian border guards in late April 2010:

The treatment was savage. They beat us and kicked us and abused us verbally. They also electric shocked me. They shocked me on my ears. I admitted that I wanted to cross the border and that we were smuggled. They were four persons and one interpreter. They said they were security forces, but they were in plain clothes. The interpreter was an Iraqi. I felt my heart was going to stop. I was sitting on a chair. I just admitted everything, but they didn’t stop torturing me.

While Human Rights Watch does not believe torture of migrants is systemic in Ukraine, the testimonies in this report indicate that it does occur. Many migrants who were not tortured nevertheless alleged that they were subjected to beatings, kicking, food deprivation, or other inhuman or degrading treatment. All of these abuses take place in a climate of impunity with victims fearful of reporting the abuse and perpetrators not held to account.

Detention of Migrants

The authorities in all facilities clearly made preparations to improve the look of detention centers prior to the Human Rights Watch visit. Of greater concern than cosmetic changes, such as fresh coats of paint, were accounts we heard of intimidation of detainees regarding their interviews with Human Rights Watch researchers, as well as indications that certain detainees were being transferred, released, or concealed to prevent us from meeting them.

That being said, physical conditions of detention for migrants in Ukraine do appear to have greatly improved in the five years since the publication of our previous report on Ukrainian migrant detention centers, On the Margins: Rights Violations against Migrants and Asylum Seekers at the New Eastern Border of the European Union. That 2005 report had documented substandard conditions of detention in migrant detention centers throughout Ukraine, including overcrowding, unhygienic facilities, poor nutrition, and limited access to recreation, natural light, and health care. While many of these concerns have been addressed, serious problems in migration detention remain including ill-treatment, lack of access to the asylum procedure for detainees, detention of children, co-mingling of men with unrelated women, co-mingling of children with adults, corruption, and the arbitrary and disproportionate use of migrant detention in general.

All of the facilities we visited in 2010 looked clean and well-ordered and none, at the time of our visit, were overcrowded. In fact, the detention centers Human Rights Watch researchers visited in June 2010 were, at most, half filled, and in some cases entirely empty.

Most of the current detainees interviewed in most locations had no complaints regarding lack of hygiene or overcrowding. The most frequent complaints were about the food, both quality and quantity, and about lack of access to lawyers, telephones, internet, and television. “Some good, some bad,” was the typical response when Human Rights Watch asked current and former detainees how detention center guards and staff treated them. Most of the allegations of guard mistreatment in migration detention centers involved shouting, shoving, and the use of racial epithets, sometimes as a result of guards’ drunkenness or loss of temper.

Ukraine’s short-term detention facilities, called Specially Equipped Premises (SPs), where migrants are held by the State Border Guard Service in the hours immediately following apprehension exhibited the worst detention conditions and treatment of detainees, according to interviews with former detainees. Conditions progressively improve as migrants are transferred from SPs to Temporary Holding Facilities, also run by the SBGS, and from those facilities to the Migrant Accommodation Centers, run by the Ministry of Interior, where conditions and treatment are better.

Migrants interviewed by Human Rights Watch who had been detained previously described some of the same clean and spacious facilities we toured in June 2010 as having been dirty and overcrowded as recently as late 2009.

Although migration detention is limited to a six-month maximum, many migrants are frustrated in their ability to challenge the legality of their detention because severely overworked Ukrainian courts are usually not able to review cases before six months have passed. In several instances, migrants said they were issued a six-month detention order but were never presented before a judge or given an opportunity to challenge their detention. Many, including children, reported that border guards threatened to keep them detained for the full six months unless they paid a bribe.

Nothing in Ukrainian law prohibits the authorities from re-arresting migrants shortly after release from detention and detaining them for another six months. Human Rights Watch met a number of migrants who had been detained multiple times.

Migration detainees in Ukraine have no consistent, predictable access to a judge or other authority or access to legal representation to enable them to challenge their detention. Furthermore, there generally is no individualized assessment of the necessity of detaining migrants or asylum seekers as required by international law. Therefore, Human Rights Watch concludes that migration detention in Ukraine is sometimes arbitrary, and therefore contrary to international standards to which Ukraine is bound.

Ukraine’s Dysfunctional Asylum System

Although in August 2010 the asylum procedure formally resumed after having been in a state of paralysis since the eruption of an intergovernmental power struggle in August 2009, the system remains essentially broken. The asylum system has been restructured eight times in 10 years, each transition resulting in gaps in protection.

In both years 2007 and 2008, 2,155 applications were filed, according to the State Committee on Nationalities and Religions (SCNR). That number fell to 1,233 in 2009. The SCNR granted asylum to 33 people in 2007, 125 in 2008, and 126 in 2009, until the authority to grant asylum ended in August 2009. As of December 2009, there were 2,334 recognized refugees in Ukraine, more than half of whom were Afghans.

While SCNR and the Regional Migration Service (RMS) were no longer authorized to grant asylum, they continued to reject asylum claims. Most asylum claims were rejected either as inadmissible to the procedure or as manifestly unfounded without a careful examination of the substance of the claim.

A serious obstruction to the functioning of the asylum system has been the failure of State Border Guard Service officials to submit applications filed by detained asylum seekers to the RMS. The number of people released from border guard-controlled temporary holding facilities because their asylum applications had been accepted by the regional migration service fell dramatically from 1,114 in 2008 to 202 in 2009. The largest drop in asylum applications filed in 2009 occurred in the Zakarpattia oblast on Ukraine’s western border where more asylum seekers are detained than in other places, such as Kyiv.

Asylum seekers interviewed by Human Rights Watch complained that their RMS asylum interviews were superficial, that interpreters were often unqualified, and that the interviewers were sometimes harsh and judgmental. An Afghan, who appeared to us to have a plausible claim, said that his interviewer told him during the interview “100 percent you will be rejected.”

Corruption in the asylum system is rife. Refugees may be recognized because they bought their protection status and many asylum seekers say they had to bribe migration officials to enter the asylum procedure, have an interpreter during the asylum interview, or to obtain documentation.

There are also important legal gaps, such as the lack of complementary protection in the Ukrainian refugee law to protect people fleeing indiscriminate violence arising from armed conflict. Consequently, Somalis are not granted refugee protection in Ukraine. Many Somalis also face an increased risk of experiencing racial violence in Ukraine, and many said they had no other option than trying to enter the EU for protection. There are no provisions in the asylum law to protect victims of trafficking.

Unaccompanied Children

Unaccompanied children face particular obstacles to access the asylum procedure and receive documentation because they can only file a claim with a legal representative and the authorities in some regions refuse to appoint legal representatives for them. There is only one known case of an unaccompanied child being granted refugee status. Decision-making is slow, and many children become adults before their asylum applications are decided, which works against their claims.

Worse, border guards may detain children for weeks in a jail-like facility euphemistically called a “dormitory.” Border guard officials put children’s safety at risk by detaining them in this dormitory jointly with unrelated adults, including girls with boys and men.

Unaccompanied migrant children often are unable to access state-sponsored accommodation and care. A majority live with fellow nationals in shared flats and pay rent. Some are unable to pay for daily expenses and rent and therefore perform domestic or other work. Those who do live in centers for asylum seekers may be housed jointly with unrelated adults, putting them at risk of abuse. Unaccompanied children are rarely enrolled in school, and most only attend sporadic language classes.

There are no age assessment guidelines, and some officials contest children’s declarations of being underage, registering them as adults instead. Others coerce children into declaring themselves as adults by threatening to keep them in detention otherwise. As a result, some children have been detained for six months. Despite the abysmal treatment these children receive in Ukraine, both Slovakia and Hungary have returned unaccompanied children under their readmission agreements. In practice, they were returned on the same basis as adults, without consideration of their vulnerability and lack of protection in Ukraine. Some returned children alleged ill-treatment, including torture and arbitrary detention by Ukrainian officials.

Refoulement

In Ukraine the most heightened risk of refoulement—the forced return of a refugee—comes as a result of extradition requests. Despite the clarity of the bar on refoulement in international and domestic law, Ukraine on February 14, 2006 forcibly returned ten Uzbeks to Uzbekistan pursuant to an extradition request, despite calls from the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) not to return them. After the fact, in May 2006, the Ministry of Justice issued a legal opinion saying the deportation was illegal. During the time of the Human Rights Watch visit in June 2010, four Uzbek nationals appeared to be the subject of extradition requests from their home country and were in various stages of seeking asylum or appealing the rejection of their refugee claims in Ukraine.

UNHCR documented that Ukraine committed refoulement against 12 persons in 2008 and 16 persons in 2009. UNHCR told Human Rights Watch, “We continue to have a difference of opinion with the Prosecutor General with respect to the application of extradition procedures to persons of concern to UNHCR.”

II. Recommendations

To the Government of Ukraine

To the President, the Cabinet of Ministers, and the Verkhovna Rada

- Ensure that sufficient state budget resources are allocated to receiving and accommodating asylum seekers and refugees and for processing refugee claims.

- Simplify the asylum procedure and the documents issued at various stages of the process so that asylum seekers are protected from arrest and have work authorization. Consider introducing a single document for all asylum seekers.

- Provide accommodation other than detention for asylum seekers while their claims are pending.

- Provide state budgeting for the free legal aid for asylum seekers that is required by law, including for unaccompanied children.

- Establish a specialized corps of administrative judges dedicated to examining cases involving migration and refugee law.

- Provide sufficient resources for administrative courts and administrative appeals courts to handle migration and asylum-related cases.

- Amend the Law of Ukraine “On Refugees” to include complementary forms of protection to protect people fleeing indiscriminate violence arising from armed conflict and other human rights abuses, humanitarian protection for circumstances such as trafficking in human beings, and temporary protection in situations of mass influx.

- Amend the Law of Ukraine “On Refugees” to ensure access of all asylum seekers to the asylum procedure, irrespective of their age. Ensure that children are supported by qualified state sponsored representatives throughout the asylum procedures as well as by lawyers, and do not make access to the asylum procedure and documentation dependent on the appointment of a legal representative.

- Repeal any provisions in law that would require persons in migration detention to pay the costs of their own detention or of their transfer from one detention facility to another.

- Prevent re-arrests and repeat detentions of migrants who have completed the maximum six months of administrative detention by allowing released detainees at least 30 days to seek means of voluntary return or other means of relief from forced removal.

- Amend the Code of Ukraine on Administrative Offenses and the Law of Ukraine on Legal Status of Foreigners and Stateless People to limit the use of migrant detention in accordance with the European Convention on Human Rights: migration detention should only be carried out when actual removal proceedings are ongoing against that person, where detention is, as a last resort, shown to be necessary to secure that person’s lawful removal, or where the person presents a danger to the community. The necessity for detention should be subject to regular reviews before administrative and judicial authorities who have the authority to order the detainee's release. Asylum seekers and children should not be detained solely for migration reasons.

- Make it absolutely clear to all security, police, and intelligence agencies that torture, beatings, extortion, and other abuses against migrants will not be tolerated and that perpetrators will be prosecuted.

- Consider steps to better integrate the government entities involved with irregular migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees so that standards and procedures will be consistently professional and respectful of human rights principles.

To the State Border Guard Service

- Immediately investigate allegations of torture and abuse of migrants in State Border Guard Service custody, including at the time of apprehension and in all phases of SBGS detention and transfer, including while other Ukrainian authorities may be conducting interrogations in SBGS facilities. Initiate criminal or other appropriate disciplinary actions against perpetrators of torture and abuse and against officials who have failed to report such abuses.

- Ensure that all detainees in SBGS custody are treated in a humane and dignified manner and that their detention fully complies with Ukraine’s international obligations governing the administrative detention of migrants.

- Ensure that detainees are not pressured or encouraged to sign papers they don’t understand. Provide a written translation of any document detainees are asked to sign and fully explain to them the content and consequences of signing such documents.

- Ensure that all requests for asylum are quickly forwarded to the regional migration service and discipline any personnel who obstruct access to asylum by discouraging detainees from applying or by not forwarding their applications.

- Refrain from detaining migrant children, both unaccompanied children and those staying with their families. Detain children only as a measure of last resort dictated by their best interests. Do not detain unaccompanied children with unrelated adults and girls with boys or men.

- Ensure that persons in SBGS custody—including those held at Boryspil’ Airport—have full access at all times to lawyers, UNHCR, and NGOs and that detainees have access to legal remedies to challenge their detention.

- Provide information about the right to seek asylum and guarantee access to the asylum procedure for foreigners in all SBGS detention facilities.

- Through recruitment and training, deploy more guards and other migrant detention facility personnel with capacity to communicate with foreigners in their own languages and, where needed, employ competent interpreters to communicate with detainees with whom no common languages are spoken.

To the Prosecutor General

- Immediately investigate allegations of torture and abuse of migrants in State Border Guard Service custody and prosecute perpetrators of torture and abuse.

- Investigate reports of corruption in migration service and SBGS detention facilities and ensure appropriate disciplinary and/or criminal action against perpetrators.

- Observe Ukraine’s nonrefoulement obligations at all times and refrain from extraditing asylum seekers to countries where they are likely to face persecution and/or torture, including by ensuring a right of appeal to a court with suspensive effect.

To the Ministry of Interior

- Stop the practice of quickly re-arresting and detaining migrants who have been released from administrative detention after reaching the maximum six months.

- Provide migrants in Ministry of Interior detention facilities a sufficient quantity of food and an appropriate and nutritious diet. Carry out inspections in migration accommodation centers to ensure standards on food provisions are observed.

- Ensure that persons in Ministry of Interior custody have full access at all times to lawyers, UNHCR, and NGOs and that detainees have access to legal remedies to challenge their detention.

- Refrain from detaining unaccompanied children and families with children. Ensure that children are detained as a matter of last resort dictated by their best interests. In the case of uncertainty whether a person is underage he or she should be given the benefit of the doubt.

To the State Committee on Nationalities and Religions

- Investigate allegations of corruption of migration service staff and ensure appropriate disciplinary and/or criminal sanctions against staff who demand bribes.

- Reserve expedited procedures for claims that are clearly abusive and manifestly unfounded. Accelerated procedures should be the exception rather than the rule and claims that are not clearly abusive and manifestly unfounded should be decided on the merits. Refrain from considering claims by unaccompanied migrant children under accelerated procedures.

- Accept asylum claims by and provide documentation to all unaccompanied children who wish to file a claim.

- Improve training and supervision of migration service refugee claim interviewers and interpreters to ensure that interviews are conducted by staff with specialized skills and knowledge of refugee and asylum matters. Applicants should be treated with respect and consideration in all phases of the process in order to foster trust and a full and fair examination of the claim, with particular sensitivity to cultural and gender difference, and for survivors of torture, sexual abuse, and other traumatizing events.

- Train migration service officials on child-specific forms of persecution and on conducting child-friendly asylum interviews.

- Grant unaccompanied children access to state-sponsored accommodation on a priority basis. Ensure children housed in these centers are able to enroll in state schools as soon as possible after their arrival. Encourage children’s integration into the local community by promoting their participation in sports clubs and other recreational events.

- Ensure that single adult men are not housed together with children in Temporary Accommodation Centers.

- Cooperate with the UN High Commissioner for Refugees and the International Organization for Migration in finding and facilitating durable solutions for refugees in Ukraine, including resettlement.

To the Ministry of Family, Youth, and Sport

- Ensure the prompt designation of state-funded competent legal representatives for unaccompanied children in the asylum procedure.

- Ensure that all unaccompanied migrant children receive protection as children deprived of a family and are able to access their entitlements to state-sponsored education and housing immediately after identification and without bureaucratic obstacles.

- Lead on the adoption of inter-agency guidelines that clearly set out the responsibilities of and cooperation among ministries and committees towards unaccompanied migrant children in Ukraine.

- Lead on the adoption of age assessment guidelines for all government bodies dealing with unaccompanied children. Age assessments should take a holistic approach that includes a child’s history and not rely exclusively on intrusive and unreliable medical exams.

To the Governments of Slovakia and Hungary

- Do not return asylum seekers to Ukraine and ensure access to the asylum procedure at all times for apprehended foreigners. Provide information on their right to seek asylum in writing and orally with the help of a competent interpreter.

- Suspend the return of rejected asylum seekers and migrants to Ukraine until such time as independent reports confirm that persons returned are treated in a dignified and humane manner.

- Suspend the readmission of unaccompanied children and members of other vulnerable groups to Ukraine, as that country is not in a position to provide protection for them. In case of uncertainty whether a person is underage, the person should be given the benefit of the doubt.

- Amend legislation to introduce a suspensive effect of all appeals against expulsion decisions. Ensure any foreigner apprehended and subject to deportation is informed of his or her right to legally challenge that deportation, and has access to lawyers, NGOs, or UNHCR to do so.

- Allow for independent monitoring at border police station at all times, and in particular of returns under accelerated procedures.

To the European Union

To EU Member States

- Suspend the return of third-country nationals under the EU-Ukraine readmission agreement until Ukraine meets international standards with respect to the human rights of returned migrants, particularly with regard to the practice of torture, inhuman or degrading treatment, and arbitrary detention and until Ukraine demonstrates the will and the capacity to provide a fair hearing to asylum seekers and effective protection to refugees.

- Develop a generous program for the resettlement of refugees from asylum countries, including Ukraine, in a spirit of international solidarity and as a means of providing legal mechanisms for refugees to find protection in EU member states and as a durable solution to their plight. Resettlement, however, should be conceived as a complement to asylum and not as a substitute to providing asylum to refugees who have entered or stayed irregularly in EU member states.

To the European Commission

- Provide assistance to Ukraine geared toward improving its capacity to receive, accommodate, and properly process the claims of asylum seekers and to protect, integrate, and provide other durable solutions for refugees, including resettlement to EU member states. In light of the decreasing numbers of detainees, consider reprogramming funds for the construction of new detention centers in Ukraine in favor of funding that will improve Ukraine’s capacity to provide greater protection for asylum seekers and refugees and more humane treatment for migrants.

- Monitor implementation of the EU-Ukraine readmission agreement with particular regard to assessing whether the right to seek asylum is respected and ensuring that all persons returned pursuant to this agreement are treated humanely.

- In cooperation with other EU bodies, including the European Parliament’s Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs (LIBE) Committee, assess Hungary and Slovakia’s compliance with European Parliament asylum directives and with their obligations under Articles 18, 19, and 24 of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights.

To the Council of Europe

- Before Ukraine takes the chairmanship of the Council of Europe in May 2011, the Committee of Ministers and other Council bodies should pressure Ukraine to fully comply with Council of Europe standards with regard to the treatment of irregular migrants and the provision of protection to those needing it.

- The Commissioner for Human Rights should conduct a country visit to Ukraine and include the treatment of asylum seekers and migrants as a key focus of his work. He should address with Slovakia, Hungary, and other EU member states their nonrefoulement obligations with regard to the return of third-country nationals to Ukraine.

- The Committee for the Prevention of Torture should visit Ukraine with a particular focus on investigating allegations of torture during interrogations at Specially Equipped Premises and Temporary Holding Facilities in the Zakarpattia region and with particular regard to facilities located in and around Chop and Mukachevo (the CPT’s September 2009 delegation visited other locations—Boryspil’ Airport, the Chernigiv Temporary Holding Facility, and the Rozsudiv Migrant Accommodation Center).

- The Council of Europe’s Parliamentary Assembly as well as its Committee of Ministers, in line with Resolution 1741(2010) and Recommendation 1925(2010), and taking into account the findings of this report, should urge Member States to suspend readmission of migrants to Ukraine until Ukraine meets international standards with respect to the human rights of returned migrants, particularly with regard to the practice of torture, inhuman or degrading treatment, and arbitrary detention, and until Ukraine demonstrates the will and the capacity to provide a fair hearing to asylum seekers and effective protection to refugees and vulnerable individuals.

To UNHCR

- Update UNHCR’s October 2007 Position on the Situation of Asylum in Ukraine in the Context of Return of Asylum-Seekers and reiterate that governments should “refrain from returning third country asylum-seekers to Ukraine as at present no assurances can be given that the persons in question…would have access to a fair and efficient refugee status determination procedure…be treated in accordance with international refugee standards or…[have] effective protection against refoulement.”

- Continue to intervene to prevent the refoulement of refugees from Ukraine in the context of extradition requests or any other manner.

- Seek to improve UNHCR’s presence in the western border region of Ukraine so that asylum seekers, particularly those in detention, have better access to UNHCR’s advice and assistance.

To the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention, the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture, and the UN Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights of Migrants

- Within the mandates of each Special Procedure, request an invitation to visit Ukraine and the neighboring EU countries to examine the treatment of migrants and asylum seekers in state custody, including detention of people who are the subjects of extradition requests. Follow up with the Ukrainian government on shortcomings and recommendations detected during previous visits to the country.

III. Methodology, Scope, and Terminology

Human Rights Watch conducted research for this report in Ukraine from May 21 to June 1 and from June 7 to June 28, 2010 with brief side trips into Slovakia and Hungary. In Ukraine we travelled to Kyiv, Vinnytsia, Chernigiv, Luts’k, L’viv, and Zakarpattia region. In Slovakia we travelled to Bratislava to meet with officials and visited the reception center for asylum seekers in Humenné. In Hungary we visited the detention facility for migrants in Nyírbátor and met with officials there and in Budapest. After an assessment of current patterns of irregular migration from Ukraine to the European Union, we decided not to include Poland in our field work. In fact, the Human Rights Watch researchers did not find a single person who said he or she had been returned from Poland among the 161 migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers interviewed.

Three Human Rights Watch researchers conducted 161 individual interviews with migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers in Ukraine, six in Hungary, and five in Slovakia. Interviews with migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers were conducted directly in English, Russian, French, and German and, with the aid of professional interpreters, in Somali, Arabic, Dari, and Pashtu. In a few cases, such as with nationals of China and some of the Pakistanis, interviewees chose interpreters from among co-national detainees who spoke some English.

Human Rights Watch interviewed 60 Afghans, 49 Somalis, 11 Iraqis, 7 Nigerians, and smaller numbers of other nationality groups from Algeria, Bangladesh, China (four Tibetans), Democratic Republic of Congo, Egypt, Germany, Ghana, India, Iran, Palestine, Republic of Congo, Russia, Sri Lanka, Syria, Tunisia, Uganda, Uzbekistan and a stateless man with ties to Armenia and Iran. The interviewees generally were young and male, mostly traveling singly and not part of family groups. The largest number of males, 76, was in the 18 to 29 age range. There were 25 boys under age 18. Of those, 19 were unaccompanied. There were 13 men in their thirties, 11 in their forties, and four in their fifties; ten males were of indeterminate or questionable age, mostly in their late teens.

Females represented 33 of the interviewees, of whom 11 were under the age of 18. Of those, 7 were unaccompanied. Seven women were in the 18 to 29 age range, four were in their thirties, four were in their forties, one was in her fifties, and six were of indeterminate age.

Individual interviews averaged about 45 minutes, and some lasted well over one hour. In some cases Human Rights Watch selected individual interview subjects in detention and reception centers from among those who indicated a willingness to be interviewed after we made a group presentation. Outside of detention centers, local service providers and migrant community members helped to identify interview subjects.

Interviews were conducted in complete privacy with no one present other than an interpreter, except for a few interviews where a family member was present, which is always indicated in the text. Two interviews were conducted by phone.

Human Rights Watch visited the following migrant detention centers in Ukraine: The Chernigiv and Chop Temporary Holding Facilities; the Rozsudiv and Zhuravychi Migrant Accommodation Centers; the Boryspil’ Airport and Mukachevo Specially Equipped Premises, and the Dormitory for Women and Children in Mukachevo, known among migrants as the “Baby Lager.” We also visited the Latorytsia Temporary Accommodation Center in Mukachevo. Access and terms of reference for the visits were subject to lengthy negotiation, but Human Rights Watch researchers were permitted to interview detainees in completely private settings of our choice.

In all cases, Human Rights Watch told all interviewees that they would receive no personal service or benefit for their testimonies and that the interviews were completely voluntary and confidential. All names of migrant, refugee, and asylum seeker interviewees are withheld for their protection and that of their families. The notation used in this report uses a letter and a number for each interview; the letter indicates the person who conducted the interview and the number refers to the person being interviewed. All interviews are on file with Human Rights Watch.

Human Rights Watch also interviewed national and local Ukrainian officials with the Ministry of Interior, State Border Guard Service, State Committee on Nationalities and Religions, and Ministry of Family, Youth, and Sport. We interviewed representatives of international organizations and local and international nongovernmental organizations in Ukraine, Slovakia, and Hungary.

In line with international instruments and Ukrainian law, in this report the term child refers to a person under the age of 18.[1] For the purpose of this report, we use the term unaccompanied child to describe both unaccompanied and separated children as defined by the Committee on the Rights of the Child:

“Unaccompanied children” are children, as defined in article 1 of the Convention, who have been separated from both parents and other relatives and are not being cared for by an adult who, by law or custom, is responsible for doing so. “Separated children” are children, as defined in article 1 of the Convention, who have been separated from both parents, or from their previous legal or customary primary caregiver, but not necessarily from other relatives. These may, therefore, include children accompanied by other adult family members.[2]

In this report, “migrant” is simply the broadest, most inclusive term to describe the third-country nationals entering, residing in, and leaving Ukraine. It is intended as an inclusive rather than an exclusive term. In other words, to call someone a migrant in this report does not exclude the possibility that he or she may be an asylum seeker or refugee. A refugee, as defined under the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, is a person with a “well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion” who is outside his country of nationality and is unable or unwilling, because of that fear, to return.[3]Refugees, it should be remembered, are people who meet the refugee definition whether or not they have been formally recognized as such. An asylum seeker is a person who is seeking protection and, as such, is trying to be recognized as a refugee or to establish a claim for protection on other grounds.

IV. Background

The name Ukraine is believed by some to be derived from okrayina, which means borderland. If so, it is well named. Ukraine is the primary borderland country that separates Russia in the east from the European Union in the west. The country’s geographic location is one of the factors that has defined its current economic, social, and political life. For centuries Ukraine has been one of the key stepping stones for east-west migration, and over the years various attempts have been made to stem migration flows at its borders. This report is about the effort to stop the flow of irregular migration to the European Union and about the impact on the lives of refugees, asylum seekers, and migrants who have found themselves stuck in a country many thought was only going to be a way station to the West.

External Dimension of EU Asylum and Migration Policy

The story of refugees, migrants, and asylum seekers in Ukraine begins, paradoxically, with the European Union (EU). This is because the people coming from Asia, the Middle East, and Africa in search of protection, opportunity, or some mix of motives, rarely choose Ukraine as their preferred destination but rather end up there when their plans to get to the European Union go awry. They wind up in Ukraine because EU member states came increasingly to see the influx of migrants and asylum seekers in the post-Cold War period as a threat to be stopped or at least controlled and in the 1990s began externalizing migration controls.

The European Union’s commitment to open internal borders created additional pressure to secure its external borders. To do so, the Union as a whole, as well as its member states (particularly those on its external frontier), has sought to engage with neighboring countries to manage and control those borders. Various proposals for externalizing migration controls—and refugee processing—outside the territory of the EU have emerged. In one example, the United Kingdom’s “new vision proposal” in 1993, suggested using Ukraine as a location for processing asylum claims outside the EU.[4]

While Member States have differed on the specifics, a consensus has nevertheless emerged to try to attenuate the entry of irregular migrants and asylum seekers into the European Union. A key part of the strategy for stopping or diverting the flow to the EU has been to build the capacity of neighboring states to stop the flow and, where possible, to provide protection in those states for people in need of international protection.

In December 2004 the European Council adopted the five-year Hague Program, which included an outline of the EU’s vision on partnership with third countries in the area of asylum and migration. The program called for assistance to third countries to improve their capacity for combating illegal migration, refugee protection, border-control capacity, and in tackling returns. The Hague Program also called for the “timely conclusion of Community readmission agreements” and it coincided with the establishment of the EU’s border management agency, Frontex, in 2005.[5]

The Hague Program was followed in 2009 by the Stockholm Program, which set out the EU’s Freedom, Security, and Justice plan for the next five-year period until 2014. It called for “dialogue and partnership” with countries outside the EU to manage migration and envisioned “the conclusion of new agreements covering the three dimensions of a comprehensive approach: controlling illegal migration (including readmission and support for voluntary return and reintegration), promotion of mobility and legal immigration, and support for development.”[6]

As it has developed in practice, the external dimension of EU migration and asylum policy has had a number of components, including refusal of entry to EU territory of persons coming from countries regarded as safe countries of origin or transit,[7] interceptions at sea of persons attempting to reach EU territory,[8] the return or readmission of persons who have irregularly entered EU territory,[9] and the strengthening of border enforcement and detention capacity in transit countries that border the EU.[10] In reality there remain few legal avenues for most asylum seekers to enter the European Union in search of protection.

Strengthening of Ukraine’s border enforcement capacity appears to have been successful both in making it more difficult for irregular migrants to enter Ukraine and as a deterrent. As Ukraine’s border enforcement capacity strengthened, it was able to repel increasing numbers of irregular migrants at the borders and ports of entry: from fewer than 12,000 refused entry in 2005, the number of foreigners refused entry rose to more than 18,000 in 2006 and to nearly 25,000 in both 2007 and 2008. The drop to 19,700 refusals in 2009 suggests the deterrent impact of the border-control measures. The deterrent effect is also indicated as at least one factor in the steady decline in the numbers of foreigners apprehended in Ukraine for suspected illegal entry. Such apprehensions have fallen every year since 2006, when 7,578 people were apprehended. The number fell to 6,762 in 2007, 4,879 in 2008, 3,684 in 2009, and 1,810 in the first eight months of 2010. Deportations show the same pattern; deportations fell from 5,406 in 2006 to 4,464 in 2007, 3,738 in 2008, 2,885 in 2009, and 1,436 in the first eight months of 2010.[11]

Readmission Agreements

Readmission agreements have become a favored EU mechanism for facilitating the return of migrants and asylum seekers to countries outside the Union.[12] A readmission agreement between two states allows each state to return to the other any person who travels from one state to the other without permission, though in the case of the EU and neighboring states the notion of reciprocity is mostly theoretical. The reality is that such agreements almost entirely work in one direction: returning people from the EU to countries outside the Union.

In theory readmission agreements are not supposed to interfere with the right to seek asylum and other fundamental human rights.[13] In practice those liable to return under such agreements include not only irregular migrants and failed asylum seekers but also asylum seekers and members of vulnerable groups whose claims for protection have yet to be determined. The agreements are also used in combination with accelerated procedures at the border that result in quick returns without a careful examination of protection needs.[14] This approach undermines the right to seek asylum as articulated in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the binding EU Charter of Fundamental Rights and conflicts with the spirit of Article 31 of the 1951 Refugee Convention which prohibits the penalization of refugees for illegal entry.[15] It also undermines states’ obligation to protect vulnerable groups including unaccompanied migrant children who “come under a State’s jurisdiction while attempting to enter the country’s territory.”[16]

More than 300 readmission agreements were signed worldwide between 1990 and 2000, of which 155 were signed between western European countries and central and eastern European countries.[17] Ukraine’s bilateral readmission agreements with Slovakia, Hungary, and Poland were signed in 1993 and entered into force in 1994. These agreements covered not only Ukrainian nationals but also citizens of third countries and stateless persons. The agreements were deficient in many ways: they lacked a specific obligation to ensure that the returnees would have their asylum claims processed in a fair and effective manner upon readmission; they did not include a prohibition of the return of asylum seekers; they did not require effective remedies which would allow returnees to lodge their asylum applications or raise nonrefoulement concerns under article 33 of 1951 Refugee Convention, article 3 of the United Nations Convention against Torture, and article 3 of European Convention on Human Rights.[18] Nor did they include any protection mechanisms for members of vulnerable groups or for victims of trafficking.

As the numbers of asylum seekers entering Europe increased in the mid 1990s, the EU began inserting readmission clauses into its association and cooperation agreements with other states – effectively making trade and other cooperation conditional on countries agreeing to readmit irregular migrants. In 1999 the Treaty of Amsterdam then allowed the European Union to enter into readmission agreements with other states as a community, thus binding all EU members and the third country.

After 2001, readmission agreements (and deportations) came to be seen as a crucial part of combating irregular migration into the EU. The June 2002 Seville European Council meeting recommended that each future EU association or co-operation agreement include a clause on migration management and compulsory readmission in the event of irregular migration and attached “top priority to … speeding up of the conclusion of readmission agreements currently being negotiated ... (and the) adoption of a repatriation programme ... by the end of the year.”[19] The first of these agreements was signed with Hong Kong in November 2002, and a total of 14 such agreements have now been adopted.[20]

The EU-Ukraine Readmission Agreement

The European Commission was granted authority to begin negotiating a readmission agreement with Ukraine in June 2002, around the same time as the Seville European Council meeting. The negotiations took four years, from November 2002 until October 2006. Ukraine was generally a reluctant negotiating partner, concerned mainly with the easing of visa requirements for its own nationals traveling to the EU. Because it is mainly a transit country, it was concerned that it would be a dumping ground for irregular migrants from Europe, particularly stateless persons or others who could not be sent anywhere else. In addition, it was concerned that because the eastern border with Russia was unclearly demarcated and poorly controlled, migrants would end up massing in Ukraine. It thus sought to delay negotiations long enough to conclude a readmission agreement with Russia—also a very difficult process, but one which met with success as the readmission agreement with Russia came into force in 2008.

The negotiations were conducted only by the executive; the Ukrainian parliament and civil society were not involved in any way. According to one scholar, the only reason that Ukraine would accept the readmission agreement at all was because its leaders during the period of negotiation hoped one day to join the EU and thought the agreement would “show that you are ready to cooperate with the EU.”[21]

On June 18, 2007, the European Union and Ukraine signed agreements on visa facilitation for Ukrainian nationals and on readmission of irregular migrants who transit Ukraine and are apprehended in the EU. The readmission provisions for Ukrainian nationals came into force in January 2009. For third-country nationals, the agreement came into force on January 1, 2010.

The agreement sets out a broad procedure for returns, including an accelerated procedure for individuals apprehended near the border, and a procedure for transiting through Ukraine. It also sets out in some detail acceptable evidence that the person meets the readmission conditions.[22]

Human rights protections in the agreement are very thin, relying on an overall savings clause that nothing in the agreement allows a party to violate their obligations under refugee or human rights law. The agreement includes almost no specific obligation (except for data protection) on any party to the agreement to ensure that migrants are treated humanely, that they have access to refugee status determination, or that they will be protected from refoulement.[23]

EU Relations with Ukraine in the Spheres of Migration and Asylum

The EU as Donor

The European Union has had a significant influence as a major donor in developing migration control and asylum systems in Ukraine.[24]The EU-Ukraine readmission agreement was predicated on a promise of EU financial and technical support for capacity building in Ukraine especially in the five years leading up to the agreement coming into effect. In fact, attached to the agreement is a Joint Declaration on Technical and Financial Support which states that “the EC is committed to make available financial resources in order to support Ukraine in the implementation of this Agreement. In doing so, special attention will be devoted to capacity building.”[25]

The EU’s expenditures to strengthen Ukraine’s border enforcement and detention capacity, however, are far greater than its funding for the development of Ukraine’s asylum system, refugee integration, or programs to resettle refugees from Ukraine to EU Member States, as will be shown below.

EU support for Ukraine for border management, migration, and asylum has come through several major funding initiatives. In the period from 2000 to 2006 the main funding source was TACIS (Technical Aid to the Commonwealth of Independent States),[26] which spent more than €35 million on migration management and border control projects in Ukraine, of which about three-quarters went to private defense and security contractors for border control and surveillance equipment and training.[27] The International Organization for Migration (IOM) received more than €8 million through TACIS for capacity building for migration management in Ukraine, including €7.2 million for the Capacity Building for Migration Management (CBMM) project that started in 2005 and continued through the end of 2008.[28] The CBMM enabled IOM to fully equip and upgrade two of the Ministry of Interior’s Migrant Accommodation Centers (MACs), refurbish and fully equip five SBGS Temporary Holding Facilities (THFs), and procure 27 modern Toyota buses to transport irregular migrants (six for the Ministry of Interior and 21 for the SBGS).[29] IOM also received €4.3 million in 2006-2007 and €1.4 million in 2008-2010, co-financed by the EU and the US Department Bureau of International Narcotics and Enforcement Affairs, for the improvement of SBGS human resources management and the upgrading of Border Guard training facilities.[30]

The UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) was, relatively speaking, the poor cousin within the TACIS family, receiving about €1.7 million from 2000 to 2006 to strengthen the asylum system and support the Söderköping Process.[31] About three-quarters of the TACIS funding to UNHCR went for building the temporary accommodation centers in Odesa and Mukachevo; the remainder went for material assistance for refugees.[32]

The imbalance between EU funding for border and migration control and protection continued during the Aeneas program from 2004 to 2006, which provided a total of €120 million over its three-year life specifically for migration and asylum-related projects.[33] A relatively small amount went to build up the asylum system or to enhance refugee protection: UNHCR received €1.3 million for its continuing engagement in the Söderköping Process in Ukraine, Belarus, and Moldova and several NGOs, including the Danish Refugee Council (DRC), Caritas Austria, and the European Council on Refugees and Exiles (ECRE), received amounts of less than €1 million each for their work on behalf of refugees and asylum seekers.[34] Through Aeneas the EU provided more funding for migration management, including €2.3 million to the International Center for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD) for technical support to the Ukrainian authorities to control irregular migration,[35] including the construction of five Temporary Holding Facilities and the equipping of another eight THFs. Through Aeneas the EU funded ICMPD to construct the perimeter security systems for the Rozsudiv and Zhuravychi MACs.[36] It also provided €1.7 million to IOM and €748,000 to the International Labor Organization through Aeneas for counter-trafficking in Ukraine.[37]

Since 2007 the EU’s primary general fund for building Ukraine’s capacity in the migration and asylum fields has switched from TACIS to the ENPI (European Neighborhood and Partnership Instrument), which covers a wide range of development projects with €494 million specifically for Ukraine for the period 2007-2010.[38] ENPI funding included €35 million to the Ukrainian State Border Guard Service and Ministry of Interior to build their capacity to deal with irregular migrants, including by constructing and upgrading migrant detention facilities, €24 million for the EU Border Mission to Moldova and Ukraine (EUBAM) itself, and €2.9 million to an engineering and technology multinational corporation, the Arup Group, and a migration research and consulting company, Eurasylum, to set up custody centers and THFs in Ukraine and technical support. Again, relatively small amounts went to enhance protection of asylum seekers and other vulnerable groups. Through ENPI, the EU provided €960,000 to the DRC for legal and social protection programs for asylum seeking and refugee children in Ukraine and €596,000 to the NGO Suchasnyk to combat trafficking in children.

The €35 million ENPI funding to strengthen Ukraine’s migrant detention capacity was through READMIT, a program specifically intended to enhance Ukraine’s capacity to receive returnees under the EU-Ukraine readmission agreement. (See Chapter VII.)[39] The EU and bilateral (Italy and Germany) funders have also provided about €2.5 million specifically to prepare for the EU-Ukraine readmission agreement through the GUMIRA Project (Technical Cooperation and Capacity Building for the Governments of Ukraine and Moldova for the Implementation of the Readmission Agreements with the European Union), of which IOM received €2 million for technical assistance to facilitate the introduction of the readmission agreement.[40]

Relative to such expenditures, the EU funding of €4.9 million to UNHCR in 2009-2010 to support the Regional Protection Support Project and the Local Integration of Refugees Project—split among Ukraine, Belarus and Moldova—has been modest.[41]

The EU has also put considerable funding into strengthening its external border on the EU side of the Ukrainian border, particularly through Frontex, the European Agency for the Management of Operational Cooperation at the External Borders of the Member States of the European Union.[42] Frontex’s reach has also extended beyond the borders of the EU into other neighboring countries, including Ukraine.[43] Frontex’s annual budget in 2009 and 2010 was €88 million.[44] Human Rights Watch is not able to estimate the amounts of Frontex’s budget that have been devoted exclusively to controlling migration from Ukraine to the EU, but a snapshot of its operations in 2008 and 2009 that involved Ukraine include Jupiter, a joint operation budgeted at €992,500 to control the EU’s eastern land borders, including by detecting irregular migrants hiding in vehicles at border points with Ukraine and neighboring countries;[45] Lynx, a €200,000 operation to enhance border control in Slovakia, particularly from Ukraine;[46] and Ariadne, a €150,000 operation to decrease irregular migration from Ukraine and Belarus with a focus on detecting false documents and irregular crossings near border crossing points.[47] Frontex also engaged in the Five Borders pilot project, a series of joint operations in 2008 and 2007 to control the common external EU borders with Ukraine, at a cost of €450,000 in 2008[48] and €350,000 for the last six months of 2007.[49]

EU Burden Sharing through Resettlement

While the EU has spent millions of Euros to control migration and to some extent build Ukraine’s asylum system, it has done virtually nothing to share the responsibility for protecting and providing durable solutions to refugees. The most tangible way to share the human burden is through resettlement. The EU’s Stockholm Program calls upon the Union to “step up its resettlement efforts in order to provide permanent solutions for refugees.”[50]

To use the phrase “step up” implies that Member States have taken some steps to develop resettlement programs. Outside of Scandinavia, such programs are still almost nonexistent. With respect to Ukraine, EU member states have provided virtually no human burden sharing as part of a managed migration scheme to provide a legal and orderly means of admitting refugees who, as yet, have very few avenues to enter EU member states legally to seek protection.

In 2009 UNHCR resettled about 84,657 refugees worldwide, approximately two-thirds of the refugees UNHCR identified as needing resettlement that year. EU member states took fewer than six percent of that number (4,810 persons). Out of the 388 individuals that UNHCR identified in Ukraine as in need of resettlement in 2009,[51] resettlement countries worldwide resettled 116—a mere 30 percent. Of these 116 individuals, EU member states took 67, due in large part to Sweden's willingness to resettle 43, a striking majority. Other EU member countries were not so generous; Portugal admitted 14, the Netherlands eight, France and Denmark each took one, while Germany, Spain, Italy, the United Kingdom, and the remaining EU countries took none.[52] These statistics are remarkably similar to the 2008 figures, which show that while Sweden accepted 50 refugees from the Ukraine, the remaining EU countries admitted only three. Similarly, in the first six months of 2010, more than half of the 92 cases UNHCR submitted were accepted for resettlement worldwide,[53] but EU member states, including Sweden, took only seven.

V. A Dysfunctional Asylum System

From August 2009 through August 2010 it was impossible to be granted asylum in Ukraine because there was no government authority authorized to do so. Although the asylum procedure has formally resumed, the system remains essentially broken. The asylum system has been restructured eight times in 10 years, each transition resulting in gaps in protection.[54] A 2007 UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) report on the situation of asylum seekers in Ukraine observed:

These continuous reorganizations, exacerbated by frequent changes in management and limited financial resources allocated by the State Budget have led to problems of access to asylum and substantive procedures, and have negatively impacted on the quality and speed of asylum decisions.[55]

The total shutdown of the asylum-granting authority of the State Committee on Nationalities and Religions (SCNR) occurred as a result of an on-again/off-again showdown between the president and Cabinet of Ministers (under the control of the Ukrainian parliament, the Verkhovna Rada), which has plagued Ukraine since independence.[56] Although the February 2010 inauguration of President Viktor Yanukovych resolved many of the tensions between the president and the current parliament that had paralyzed government functions in many areas in 2009, the struggle nonetheless continued for months.

The specific controversy that resulted in suspension of the asylum system for a year was the Cabinet of Ministers’ decree on June 24, 2009 to establish a State Migration Service (SMS) under the authority of the Ministry of Interior that would transfer the Department on Refugee Affairs from the SCNR and merge it with the new SMS, effective August 1, 2009. Then President Viktor Yushchenko vetoed the Cabinet of Ministers’ decree, so that no authority—neither the SCNR nor the never-established SMS—had legal authority to grant asylum.[57] The situation was finally resolved through a July 2010 Cabinet of Ministers decree that reinstated the authority of the SCNR to grant asylum status.[58]

The resumption of asylum processing occurred without changing any of the authorities or procedures that had been in effect at the time it was suspended. When it functions, in theory, asylum seekers start the process by lodging an application for asylum with the Regional Migration Service. This is more difficult than it sounds, as numerous asylum seekers told Human Rights Watch that they filled out multiple applications and never heard any response, or were told that the border guards to whom they had submitted the applications had destroyed them or thrown them away. Unaccompanied children face particular obstacles as they are barred from accessing the asylum procedure on their own without a legal representative and in many cases the authorities fail to appoint one to represent them.

After submitting an application, there is, in principle, a ten-day period to assess admissibility, after which the applicant is to be informed whether the application has been accepted into the system. While a decision on admissibility is pending, the applicant is issued a green document, which is valid for 15 days. From that point, the authorities are supposed to conduct additional assessments of the claim. Applicants who are in the country illegally remain in detention during this time.

The SCNR was created as an independent agency that is not part of the Ministry of Interior. The Regional Migration Service (RMS), operating in 24 regions (oblasts) under the supervision of the SCNR, receives the asylum applications and conducts admissibility interviews. After receiving an application the RMS can:

- refuse the application within three days if there is no basis for the claim or the claim has violated procedures, and then the person does not even receive a green document;[59]

- accept the application and issue a green document but then refuse to process the application within 15 days if it is manifestly unfounded or abusive;[60] or

- accept and process the application and issue the applicant a pink card to indicate that he or she has been accepted into the procedure.

The pink card does not indicate a grant of asylum but rather allows the applicant to remain temporarily pending the outcome of the procedure and includes work authorization. The RMS is not authorized to grant or refuse refugee status, but has the responsibility to examine the claim once an asylum application has been admitted into the procedure and to make a refugee status recommendation to the SCNR. The law allows the RMS a maximum of three months to gather information about the claim, conduct a medical check, and prepare a file with a recommendation on refugee status to SCNR.[61]

SCNR then has a maximum of a further three months to decide the claim. This means that no one, in principle, should have a pink card longer than six months. The card itself has no expiration date but needs to be stamped every two months to maintain its validity.

In both years 2007 and 2008, 2,155 applications were filed, according to the SCNR. That number fell to 1,233 in 2009, and the largest drop occurred in the Zakarpattia oblast on Ukraine’s western border. The SCNR granted asylum to 33 people in 2007, 125 in 2008, and 126 in 2009, until the authority to grant asylum ended in August.[62] As of December 2009, there were 2,334 recognized refugees in Ukraine, more than half of whom were Afghans.[63]

While SCNR and the RMS were not authorized to grant asylum during the period of suspension, they continued to reject asylum claims. In the first six months of 2010, 524 asylum applications were lodged with the RMS. The RMS rejected 51 of these applications as inadmissible to the procedure. They acted on 405 cases, rejecting more than half of them, 220, as manifestly unfounded. Most asylum claims, therefore, are rejected after a cursory examination either as inadmissible to the procedure (under article 9 of the Law of Ukraine “On Refugees”) or as manifestly unfounded (under article 12 of the Law of Ukraine “On Refugees”). The reasons for rejecting applications as inadmissible or manifestly unfounded are not provided in the written notifications to rejected claimants.[64]

If the case is admitted to the procedure by the RMS, the SCNR then makes a decision on the refugee claim that can then be appealed to the courts.[65] However, between August 2009 and August 2010 the SCNR made no decisions on asylum applications forwarded from the RMS because the SCNR was stripped of its legal authority to decide asylum claims.

According to Natalya Naumenko, the director of the Refugees and Asylum Seekers Department of the SCNR, by June 2010 there were 750 pink-card holders the RMS had accepted into the procedure that were backlogged for a first decision because SCNR was not authorized to grant asylum.[66] There were another 340 cases of asylum claimants who had been rejected prior to August 2009 who were appealing their rejections but who were also stuck because neither the courts nor SCNR were authorized to decide their cases. Consequently, about 1,000 asylum cases were in limbo at the time of the Human Rights Watch visit.

Denied asylum seekers have the right of appeal, although the administrative court is not authorized to grant asylum but only to remand cases to the SCNR with recommendations, including returning asylum seekers to the first stage of the process. The office of the prosecutor is also able to issue a protest of an SCNR decision and to challenge a case in court. If the SCNR accepts the protest, it can start the case over, taking into account the objections the prosecutor had to the way it had been previously conducted.[67] Persons appealing denial of refugee claims before the courts are, in theory, issued a grey document, and those with appeals before the SCNR are, in theory, issued a yellow document.

The reality, however, from August 2009 to August 2010 was that the SCNR was not only not authorized to grant asylum, but also was not authorized to issue the yellow or grey documents to those who had been rejected prior to August 2009, which meant, in effect, that hundreds of people with claims pending before the courts and the SCNR had no way to prove to police on the street that they were authorized to be in the country and not subject to arrest, detention, and deportation.

Consequently, in June 2010, Naumenko told Human Rights Watch, “People appealing decisions are not documented. They have effectively become illegal. We cannot implement decisions of the courts on refugee cases.”[68] She said that 340 people whose cases were rejected before August 2009 were in this situation. She pointed to a stack of files on the floor of her office to let Human Rights Watch know she was aware of these cases and would begin processing them as soon as her agency was authorized to do so.

In the meanwhile, asylum seekers with cases pending in the courts remain extremely vulnerable because no agency has issued them the relevant document indicating they have permission to stay while their case is pending. A 37-year-old Iraqi who applied for asylum shortly after arriving in Ukraine in May 2008, whose claim was rejected but on appeal in the courts, told Human Rights Watch that police stop him in Kyiv about twice a week to check his documents. All he has is a UNHCR-issued a protection letter, which has no legal weight in Ukraine, so he has been taken multiple times into local police stations, arrested at his place of work and fined for working without authorization, or harassed and extorted by police on the street. The latter treatment has actually been preferable to him to the alternatives. He has allowed the arresting police to empty his pockets of what money he has or on other occasions has chosen to pay them 200 hryven’ directly rather than spend a couple of nights in police lock up. He told Human Rights Watch:

For some police the UNHCR document is no problem, but for others it is a problem because they want money. They know if they take me to the police station, I would rather pay bribes than stay in detention until a court hearing. The court will fine me 350 hryven’ for not having documents, so I would rather pay the police 200 or 250 hryven’ [and avoid detention and the higher court fine].[69]

Access to Asylum: The Failure of the SBGS to Forward Asylum Applications or to Inform Detainees of the Asylum Procedure

A serious obstruction to the functioning of the asylum system has been the failure of Border Guard officials to forward applications submitted by detained asylum seekers to the Regional Migration Service. It does not appear to Human Rights Watch that a pre-screening system is taking place through which the SBGS makes an eligibility determination prior to the RMS performing that function. Rather, this appears to be a highly informal, ad hoc practice involving many Border Guard officials who either don’t bother forwarding applications submitted to them or actively block asylum seekers from lodging claims.

There is a perception within the State Border Guard Service that the refugee law is too generous and that migrants abuse the asylum system: “Our main obstacle [to stop irregular migration] is the liberal legislation, in particular the law on refugees,” Major General Borys Marchenko told us. He said that “at any stage of the administrative procedure a foreigner can lodge an application and is released:”[70]

They use the asylum procedure to get out of detention and into a reception center. They break the rules of their stay in Ukraine and don’t wait for the decision but use the asylum procedure to cross into the EU. Ukraine has the most liberal refugee law in the world. In no other place can a person use a refugee status application to get released from detention and abuse the system. This is a big problem and completely unacceptable. They do not want refugee status in Ukraine or in any EU country, they just want [to use] this status to live and work.”[71]

The number of asylum applications forwarded by border guards fell dramatically from 1,114 in 2008 to 202 in 2009 and in the first eight months of 2010 dropped to 88 applications.[72] Although this drop in applications should be seen in parallel to the overall drop of migrants apprehended in Ukraine, dozens of people interviewed by Human Rights Watch complained that they had tried to submit asylum claims while detained in THFs, and never heard anything more about them. For example, a Somali who was detained at several places, including the Baby Lager, Chop, and Zhuravychi, said that he wrote the asylum application nine times, but never heard any confirmation that RMS had received it.[73] A 25-year-old Iraqi told Human Rights Watch both that he was not able to file asylum applications via the border guards, but also that authorities who may have misidentified themselves to him had him sign papers he didn’t understand that may have said that he opted for voluntary return and thus would be precluded from applying for asylum:

They used to bring papers and asked us to sign and we didn’t know what we signed. We signed a lot of papers. I met some lawyers. They said they were from UNHCR. They didn’t give us any help at all. I demanded and submitted an asylum application…. The first time I applied with four other detainees for asylum. We gave [the applications] to the security guard in Chop. After, I met with a lawyer who said, “Why didn’t you write an application?” The lawyer said maybe the application ended up in the rubbish. He said we should write again. We wrote another application but I have never seen a lawyer again.[74]

The International Organization for Migration (IOM), which is engaged in providing technical support to the government of Ukraine in migration management, issues monthly reports as part of the observatory mechanism of GUMIRA, an EU-funded capacity-building project in Ukraine and Moldova. IOM’s monthly report for September 2009 noted that the SBGS forwarded three asylum applications to the Regional Migration Service that month out of the 13 migrants in Chop who consulted with the NGO there on asylum. All three were rejected. The report said, “Although the number of applications is not high, there are cases when applications submitted to the detaining authority are not transferred to the local migration service.”[75]

In some cases, detainees have not submitted asylum applications because SBGS officials did not inform them about the option of submitting an asylum claim. SBGS officials briefing Human Rights Watch before our visit to Chop informed us that they were preparing to deport three Chinese migrants being held at the facility. The three—all of whom were Tibetans fleeing persecution—had no idea that they had the right to apply for asylum. One, who said that his only communication with the guards had been through sign language and who also said that he had never been allowed to make a phone call, told Human Rights Watch:

Here they don’t say anything. We don’t want to return to Tibet. No one spoke of a refugee application or asylum. I never heard of that before. I left Tibet because of no freedom, no human rights. I follow the Dalai Lama. If we were to return to Tibet, the Chinese police would hurt us.[76]

In a letter to Human Rights Watch responding to the findings of this report, the State Border Guard Service denied that SBGS officials have failed to forward asylum applications, and cited as confirmation of this that 104 asylum applications had been forwarded in the first nine months of 2010 and that all 104 asylum seekers were released from detention on the basis of documents issued by the Regional Migration Service. The letter said that a single instance of an untimely submission of an asylum application had been identified in September 2009 in Mukachevo and that disciplinary actions were taken against the responsible officials.[77]

Asylum Interviews

Asylum seekers in detention rarely spoke to Human Rights Watch about their RMS interviews at all. Those who did indicated that the attitudes of the interviewers ranged from uncaring to hostile. An Afghan family with severely disabled children talked at length with Human Rights Watch about their experiences in Afghanistan and their difficulties in Ukraine. The father had been a school teacher in Afghanistan who had run afoul of the Taliban for refusing to teach religion in his classroom. The Taliban declared him an infidel and said they would kill him and subject his daughter to a forced marriage. He was detained together with his wife and children at the Zhuravychi MAC. He talked about his asylum interview: