On September 27, 2020 a shell killed Victoria Gevorgyan. She was just 9 years of age. The shell landed in the yard of her home in the Martuni region of Nagorno-Karabakh. On the same day, in the Azerbaijani town of Naftalan, a shell killed Shahriyar Gurbanov, 13, and his cousin Fidan Gurbanova, 14, and three other members of the family while they were in the yard of their home.

During the next six weeks, more than 150 civilians were killed in fighting between Armenia and Azerbaijan over Nagorno-Karabakh according to reports. Victoria, Shahriyar and Fidan were not the only children among the dead: another 10 Azerbaijani children also perished. The conflict forced tens of thousands from their homes, at least temporarily.

During the fighting and afterwards, Human Rights Watch researchers visited sites that had been attacked in Azerbaijan and Armenian-controlled areas of Nagorno Karabakh to investigate whether the armed forces were following their obligations under the international laws of war to protect civilians from attack. We interviewed eyewitnesses, reviewed photographs and videos captured in real time by local residents on their mobile phones or published in the media, and examined satellite imagery to reach our conclusions. We met and corresponded with the respective authorities of Armenia and Azerbaijan and the de facto-authorities of Nagorno-Karabakh.[1]

This report looks at what happened to schools during the fighting between September 27 and November 9 and reveals some of the consequences of the conflict for school children.

According to official data, at least 71 schools on the Armenian side, including two in the Republic of Armenia, and 54 Azerbaijani schools were damaged or destroyed, as well as dozens of kindergartens, arts schools, sports schools, and vocational schools.

Schools on both sides had closed in March 2020 due to the Covid-19 pandemic. They had just reopened in mid-September but closed again when the fighting began. Many schools were repurposed as shelters for the displaced. In Nagorno-Karabakh, some schools were also used as military hospitals and barracks; some were looted by local residents and Armenian military forces.

|

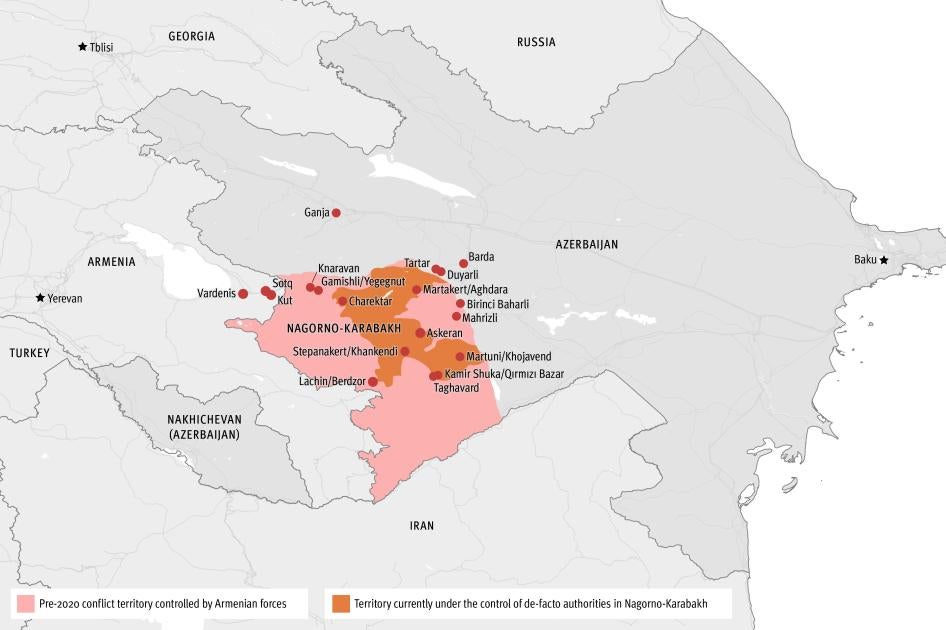

Schools in both Armenia and Azerbaijan still memorialize the alleged war crimes committed by the other side in fighting that began in 1988 and escalated with the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. Armenia and Azerbaijan, which had both been republics of the Soviet Union, re-emerged as independent states amidst conflict over territory that forcibly displaced over one million civilians. Nagorno-Karabakh, an ethnic-Armenian majority enclave in Azerbaijan, declared independence in 1991, but it has not been recognized by any United Nations member state or by multilateral organizations. By the time of the ceasefire in 1994, ethnic Armenian forces had taken control of seven Azerbaijani districts around the Nagorno-Karabakh enclave, creating a security buffer zone and a land connection to Armenia. |

October 2

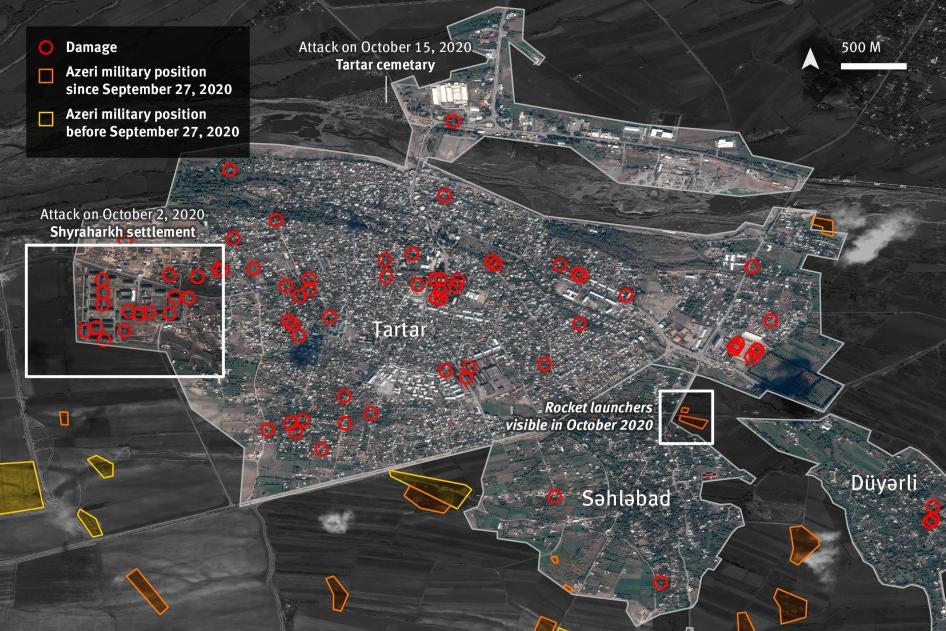

The Azerbaijani city of Tartar, on an ancient caravan route, was well within range of rockets and heavy artillery fired from the Armenian side during the fighting. Nearly every storefront on the main street was shattered when we visited. Satellite imagery from the time shows the town of Tartar was full of military transport trucks and ringed with military positions during the fighting.

Nonetheless, Armenian forces’ repeated use of imprecise, explosive weapons systems to attack densely-populated civilian areas inside the city was indiscriminate and therefore unlawful, we concluded at Human Rights Watch.

On October 2, a resident took a video of the dust and debris rising seconds after an artillery shell fired from the direction of the Armenian lines is heard slamming into a kindergarten in Shikharkh, a neighborhood built for people displaced by the war in the 1990s. Human Rights Watch verified the video, matching it with satellite imagery.

October 3

The next day, three artillery shells hit downtown Tartar’s School No. 1, pockmarking the red brick walls and flagstones of the courtyard, smashing window-frames and glass, damaging classrooms and shattering the windows of the kindergarten across the street.

As we examined the damage, the school guard told us there had been 1,300 students enrolled before schools closed due to the fighting.

Many civilians in Nagorno-Karabakh (referred to as Artsakh by Armenians) said there was nowhere in the enclave or surrounding districts where they felt safe from Azerbaijani shelling. Most women and children evacuated to Stepanakert (called Khankendi by Azerbaijan), the capital and largest city of the enclave, and then to Yerevan, Armenia’s capital, or other locations in Armenia.

When their village came under shelling from Azerbaijani forces, Narine Khachaturyan, 51, took her two daughters, one of whom was only 10, and fled for what she hoped would be the safety of her parents’ apartment in Stepanakert.

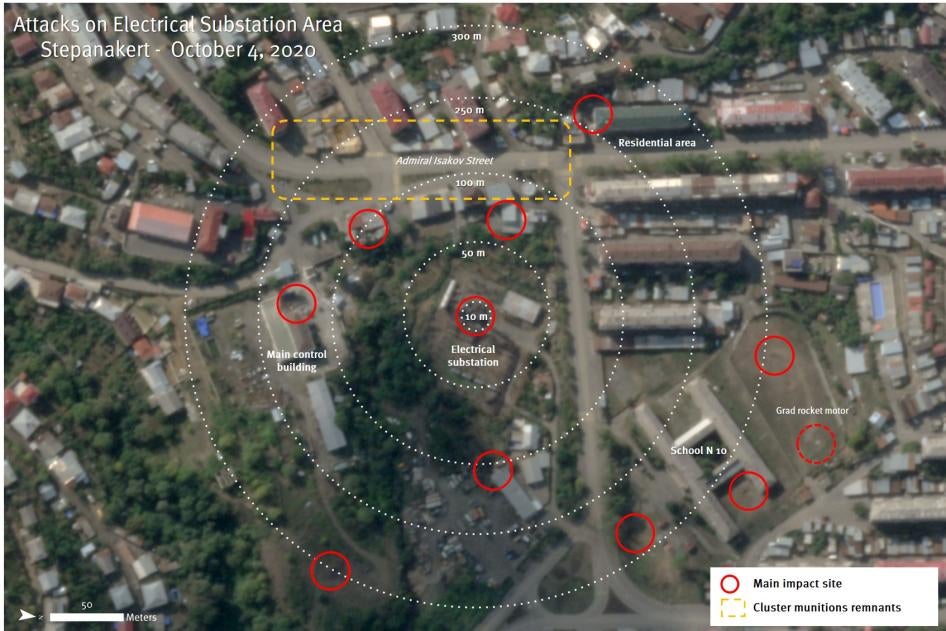

October 4

Stepanakert proved to be far from safe. Because of the shelling, the family stayed in the apartment building’s basement along with the other remaining residents, and Narine went up to the apartment to cook meals for her parents and children. At 8 p.m. on October 4, when she was in the middle of making dinner, “suddenly, there was this roar, and glass flying everywhere.”[2]

That same attack badly damaged Stepanakert’s School No. 10, across the street.

Attacks targeting the nearby main electrical substation struck the school at least six times over the course of the conflict, putting dozens of classrooms out of commission and cutting the school’s electrical and water supply.

We concluded that Azerbaijan used munitions with wide-area effects, including fundamentally-inaccurate artillery rockets, and that the strikes may be indiscriminate and therefore unlawful.

Like Tartar’s School No. 1, Stepanakert’s School No. 10 used to have 1,300 students. As of early March 2021, only a third of the school was back in use.[3]

Other schools damaged by shelling in Stepanakert during the conflict include School No. 12, Kindergarten No. 1, a music school, and the kindergarten of the Armenian Evangelical Association, local de facto authorities told us.[4]

Following the October 4 attack, Narine and her two daughters, ages 10 and 25, who both have multiple disabilities, fled again. As of February 2021, they were sheltering at a school for the deaf in Yerevan, along with several other families displaced by the conflict.[5]

October 5

In Tartar, School No. 5, a few hundred meters from School No. 1, was hit. The attack destroyed classrooms, electrical wiring, windows, and the computers that teachers had used to provide online classes, the school director said in an interview.

Another attack in mid-October involving at least three artillery shells damaged the Shikharkh secondary school and shattered the floor-to-ceiling windows of the music school across the street, said Javad Agayev, 30, whose apartment is across the road from the school.[6]

At the start of November, when we met a senior public official in Tartar who asked not to be identified, he was wearing a grey and olive-drab camouflage uniform. He took us into a bunker beneath the regional administrative complex in downtown Tartar, where he read out a long list of alleged war damage. Fourteen public schools, three kindergartens, and a vocational school were damaged or destroyed, he said, and 17 civilians had been killed and 10,000 of the region’s 114,000 residents had relocated.[7] We were able to visit and verify five attacks that damaged schools in the region.

We found one Azerbaijani military truck parked behind the back wall of School No. 1 on November 8.

Dr. K. Mammadova, who teaches veterinary sciences at the Agricultural University of Ganja, Azerbaijan’s second largest city, recorded the exact time on October 5 when her own former school, Secondary School No. 4, was damaged: 2:37 a.m.[8]

The artillery rocket that hit the street opposite the school’s back entrance was a Russian-made Smerch (“Tornado”), according to the national demining agency: 7.6 meters long, carrying 258 kilograms of high explosive. The explosion blew out windows and doors on the school’s back wing, tore through classrooms, and smashed the windows on the opposite side of the inner courtyard.

The school had 3,200 students enrolled, a guard said.

October 8

At 11 a.m., another Smerch rocket hit the yard of Secondary School No. 5 in Barda, the third largest city in Azerbaijan, witnesses told us. The school was closed to its 1,500 students, but was sheltering 300 people displaced from their homes by the fighting, and 15 teachers and other staff were also present, said the school director, Teymur Hamidov. Five people were injured. The rocket had apparently released its deadly warhead before hitting the ground, and was half-buried, with its tail fins “sticking up three meters in the air,” Hamidov said.[9]

October 14

At 10 a.m., two heavy artillery shells hit the yard of the village school in Duyarli, two kilometers southeast of Tartar city. A third shell hit the roof, blasting through five classrooms and setting the building on fire.[10]

Teacher Arzu Guliyeva, 57, was at home across the road. Fragments from the shells perforated her roof. Her husband tried to call the fire department, but the phone had been cut as a result of the attack, “so he shouted at a car that was passing by to tell the firefighters to come,” she said.[11]

Residents and firefighters had just gathered to battle the flames when a fourth artillery shell hit. A local representative named seven civilians who were wounded.

Namig Suleymanov, 44, whose wife is a teacher at the school, showed us two small impact craters on the school grounds where we found fragments of artillery shells. Behind the school we saw an L-shaped trench in the ground—it was a bomb shelter, Suleymanov said, dug as part of a plan to use the school as a base for civilian firefighters during the fighting, so they would be protected from incoming shelling.[12] The plan was scrapped due to the attack.

Azerbaijani forces positioned near Duyarli likely increased the risk of Armenian attacks hitting the town. Satellite imagery from October shows there were 10 Azerbaijani firing positions in a field southeast of Duyarli, one just 10 meters from a house. There were also three heavy artillery guns 800 meters west, four rocket launchers 1.5 kilometers north, and two more rocket launchers 2.5 kilometers southwest.

Nonetheless, the presence of these military objects neither explains nor excuses the heavy artillery shelling of the school. Any deliberate targeting of a school and civilian responders would be a war crime.

Armenian authorities also reported that Azerbaijani drone strikes damaged two middle schools in the Armenian villages of Sotq and Kut, near the town of Vardenis, and told us that at 9 a.m. on October 14, a drone strike seriously wounded a 14-year-old boy on his way to pick potatoes in an agricultural field near Sotq with other civilians.[13]

October 15

In Karmir Shuka (Qırmızı Bazar in Azerbaijani) a village in Nagorno-Karabakh, the only school “suffered a lot of damage,” an education ministry official said.[14] Armenian forces began using the school as a field hospital for wounded soldiers in October, according to a nurse practitioner from a neighboring village.[15] A sign in the village that said “Hospital” pointed to the school. The worst damage may have been caused during an attack on the village on October 15. When we visited in November, the first floor of the school as well as the yard were littered with damaged flak jackets, bloodied uniforms, rags, and stretchers. We also saw multiple artillery fragments in the yard, and all the windows in the school building were shattered.

October 17

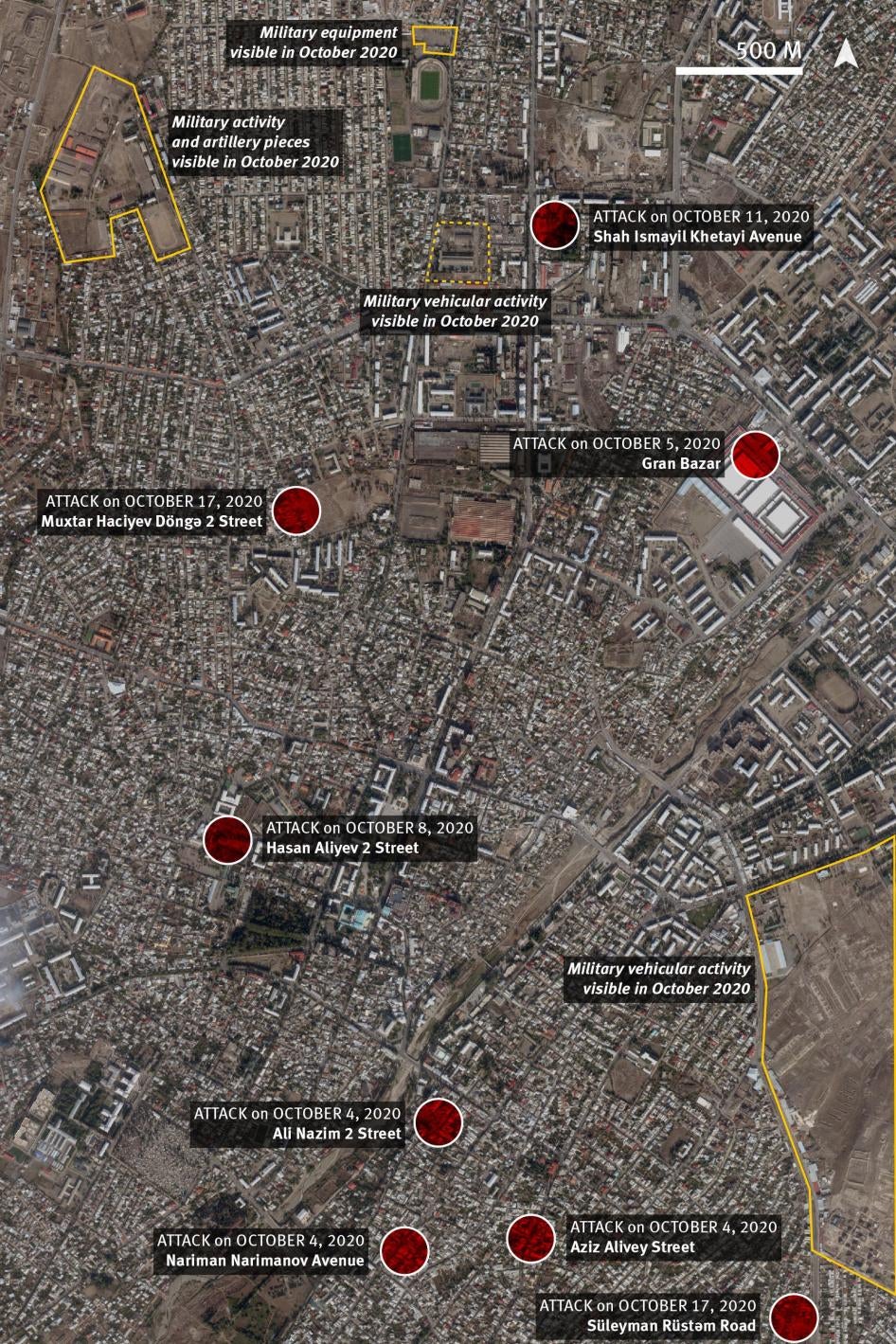

At around 1:30 a.m., two Scud-B ballistic missiles hit Azerbaijan’s second-largest city, Ganja, killing 21 people. The blast from one missile flattened homes in the Mukhtar Hajiev neighborhood and ripped through both Kindergarten No. 10 and Secondary School No. 29, 250 meters away. It even shattered windows at School No. 18, 850 meters from the impact point.[16] The attack killed ten civilians in their homes, four of them children who had been students at School No. 29: Orkhan, 11, and his sister Maryam, 6, as well as their sister and mother; Arthur, 13, whose grandmother had adopted him; and Nigar, 14, who was killed along with four other family members.[17]

The school’s courtyard was littered with shards of glass, splintered wooden window frames and a few smashed chairs and desks. A school administrator, who was surveying the damage, told us that the school had lost contact with students whose homes were destroyed, “and it’s been impossible to trace where they are, so we can’t provide them with distance learning,” as staff were trying to do for other students.[18]

Scud-B missiles can carry almost 1,000 kilograms of high explosives. Produced in what was then the Soviet Union beginning in the early 1960s, the missiles have an error radius of hundreds of meters. Such weapons make up for their inaccuracy by spreading destruction over wide areas. Armenian leaders claimed to have been targeting military objects in Ganja, and our satellite imagery analysis confirmed that some military objects were present, but it was nevertheless unlawful to use such an indiscriminate weapon in a densely-populated city.

October 19

The “Line of Contact” that had separated Armenian and Azerbaijani armed forces since the First Nagorno-Karabakh war ended in 1994, cuts through Azerbaijan’s Aghdam region.

Just a few kilometers from that line lies the settlement of Birinci Baharli, built for people displaced in the 1990s. On the afternoon of October 19, a salvo of around 10 Grad (“Hail”) artillery rockets—designed to destroy units of infantry soldiers and military vehicles—hit and severely damaged the village’s School No. 1, which had 180 students before it was closed due to the fighting, residents said.[19]

Two other rockets hit the school’s kindergarten, about 100 meters away, which had been renovated in early 2020 and had 35 students.[20]

*********************

In the town of Martuni, 40 kilometers east of Stepanakert, Mihran Jivanyan, then director of School No. 2, was one of a handful of civilians who stayed throughout the war. “No electricity, no people, it was tough,” he said.

On different days, Azerbaijani artillery fire concentrated on different areas of town, which Jivanyan said was especially terrifying because it was so “unpredictable.”[21]

Armenian authorities told us that School No. 2 was shelled repeatedly between October 1 and October 15.[22] In fact, the worst damage was likely caused by a devastating salvo of Grad artillery rockets on October 19, which also severely damaged the music and arts school in the town’s “House of Culture,” directly across the square from School No. 2. A group of visiting researchers with the International Partnership for Human Rights (IPHR) narrowly escaped the attack.[23] School No. 2 was hit again on November 8, just two days before the ceasefire, Jivanyan said.

Jivanyan went to take stock on November 10. “One [Grad rocket] hit the roof and fell through the ceiling, three hit the school yard, two hit the fence and one hit the ground next to the entrance to the school basement,” he said. The second floor was severely damaged, and we saw remnants of at least three Grads, two in the schoolyard and one in the second-floor classroom corridor, during a visit on November 23. All the buildings in the immediate vicinity had their windows shattered and notable structural damage, including a kindergarten, a library, and the district administration building.

October 23

As Askeran, a district center in Nagorno-Karabakh, 15 kilometers north of Stepanakert, came under intense artillery fire, the basement of the local School of Arts and Music was transformed into a temporary hospital. Doctors and local residents seeking care as well as people trying to shelter from attacks were there when a rocket hit a car two meters from the back of the building at 6:30 p.m., local education officials said.[24]

The school building sustained severe damage. Surprisingly, no one in the basement was wounded.

November 2

In the village of Mahrizli in Azerbaijan’s Aghdam district, also just a few kilometers from the then “Line of Contact” with Armenia, a shell hit the primary and pre-primary classrooms in the town’s only school at 6 a.m., blasting through walls and destroying doors, windows and desks.[25] An artillery attack on October 10 had already hit the school yard. The school had about 300 students and 35 staff.

After the Ceasefire

On November 9, the day after Azerbaijani forces captured control of the city of Shusha—Armenians call it Shushi and had controlled it since the 1990s—the president of Azerbaijan and the prime minister of Armenia, signed a Russian-brokered ceasefire agreement, ending all hostilities.

Under the terms of the ceasefire, Azerbaijan reclaimed 15 percent of Nagorno Karabakh and all of its seven other previously-occupied districts.

At least two thousand Russian troops in the role of peacekeepers have been deployed in Nagorno-Karabakh, where they are due to stay for the next five years.

Residents left the areas that were slated to be handed over to Azerbaijan. In some towns the residents burned houses and other infrastructure before leaving. The Nagorno-Karabakh/Armenian military and local authorities were apparently also involved in the burnings.

On November 22, we visited Yeghegnut, a village in the Kelbajar district, where the school was still burning. Military vehicles were parked in front of the torched building, and four servicemen were dismantling a field kitchen and picking up flak jackets in the schoolyard, which was littered with opened Armenian military food supplies. We also saw burned-out schools in the villages of Knaravan and Charektar.

In September 2020, there had been 220 schools in Nagorno-Karabakh, with nearly 24,000 students.[26] By November, 107 of those schools, that had enrolled 6,834 students, as well as 4 art schools and 4 sports schools for about 1,750 students, were under Azerbaijani control.[27]

After the ceasefire, civilians who had fled for safety began to return to the areas of Nagorno-Karabakh that remain under Armenian control. Armenian civilians who used to live in territory that is now controlled by Azerbaijan remain displaced in Armenia or have moved to these Armenian-controlled areas of Nagorno-Karabakh. Schools in these areas faced multiple obstacles to reopening for students. Schools served as temporary shelters for displaced civilians as well as barracks for troops that had been fighting for the Armenian side. Many school buildings were at least partly repaired, but some schools remained virtually vacant due to security concerns. Returning staff found that many classrooms had been looted.

In Martuni, under Armenian control, mortar rounds as well as Grad rockets had hit School No. 1 five times in early November, according to staff. Windows were blown out, the roof was damaged, a classroom was totally destroyed, and in the assembly hall the ceiling had collapsed and there were Grad remnants on the ground. But before repairs could begin, soldiers from the 2nd Artsakh (the Armenian name for Nagorno Karabakh) Defense Unit, which had been stationed outside Martuni during the war, moved into the school on November 10.

During a visit in November we saw troops billeted in classrooms and in the kindergarten next door, and military vehicles and weapons in the schoolyard. They cleared out by December 19.[28]

“As soon as they left a room, we rushed into that room to start cleaning. We were practically chasing them out with mops, we were so eager to re-open,” because 200 students had returned to town, said a member of the school staff. With war damage compounded by five weeks of use as a barracks, “the building was in a sorry state, as you can imagine. We did all the cleaning and all the small repairs by ourselves,” the staff member said.

Staff found that unknown persons had looted the school. “Our computers were stolen, all of them,” including eight tablets and two laptops that had just arrived and were still in their boxes when the war started, a staff member said. “The equipment from the chemistry lab was stolen. Our Xerox machines were stolen and so were the phones.”

Despite it all, School No. 1 reopened on December 21. By mid-February, 464 out of 544 former students had returned, along with 93 new students whose former communities were now under Azerbaijan’s control.[29]

School No. 2 also reopened, albeit without computers or sports equipment. Nearly all of its 430 students returned, and additional newly-displaced students were expected, according to Mihran Jivanyan, the former director, who was promoted since the ceasefire. “We’ll have more students than we had before the war,” he said.[30]

The school in Karmir Shuka, converted by the Armenian armed forces into a hospital for injured fighters, reopened in January.

The Armenian authorities claim that “no military facility was located in or near the areas … targeted by the Azerbaijani armed forces, including schools and kindergartens, and … neither they nor their property were used for military purposes.”[31] In the case of Karmir Shuka, while all hospitals are protected under international law and can never be a legitimate military target, it is misleading to imply the military made no use of school property during the conflict.

After the ceasefire, there were also several problematic cases of military use of schools. When we visited the mountain town of Berdzor (Azerbaijan calls it Lachin) in late November, for example, School No. 1 was being used as a barracks. It had been damaged in a rocket attack late at night on November 8, said a serviceman, whose own home was in an area taken by Azerbaijan. The town was evacuated because Azerbaijani forces were on “both sides of the road,” an education official told us.[32] Under the ceasefire deal, Azerbaijan re-took control in December.

Some schools that remained in Armenian hands were closed due to their proximity to Azerbaijani forces, while still others re-opened but were nearly empty, as parents were afraid to send their children back.[33]

Both aspects of the post-war reality have hit the mountainside village of Taghavard, formerly under Armenian control. The upper part of the village used to have 600 residents and its own school, but the residents fled during the hostilities. It is now under Azerbaijani control, and the school is not functioning. Halfway down the road to Lower Taghavard, a heap of boulders represents the line of division, with Azerbaijani and Armenian military positions some 50 to 60 meters apart, but no Russian peacekeepers.

Lower Taghavard remains under Armenian control but few of its 700 residents have returned, and just four of 52 students were back in school, the director, Margarita Sahakyan, told us in February. “Everyone is scared. And at night there is shooting ... Our military and their military, they shout, call one another names, then they begin shooting.”[34] The school was damaged by two mortar rounds, one near the entrance and one at the back, in an attack in late October or early November, school staff said. They had made “essential” repairs to the roof, door, and windows, Sahakyan said, but “someone stole our computer and the assault rifle our military education instructor kept locked in his office.” At a faculty meeting that was ongoing when we drove up to the school on February 20, staff said the school needed help from local authorities or from Russian forces, especially “a metal wall by the perimeter of the school fence – this way at least, the children will be safe to play in the school yard.”[35] We found mortar-round fragments.

Throughout Nagorno Karabakh the authorities have had to perform educational triage, due to extensive school damage, an influx of displaced children, and the urgent need to address months of lost schooling. They were able to repair and reopen damaged schools but lacked the resources to reopen damaged kindergartens in the villages of Aygestan and Shosh in the Askeran district,[36] and in Stepanakert, where only part of School No. 2 is still usable. “We could not open pre-school classes for 178 kids,” said Raya Musayelyan, with the education ministry in Stepanakert. Other schools had to introduce two shifts of classes, from early morning to late in the evening, due to damage and to the need to accommodate children whose schools are in areas now under Azerbaijan’s control.[37] In the Martakert district (referred to as Aghdara by Azerbaijan), where nine of 31 schools were damaged, nearly all of the 3,300 former students have returned, but so have children displaced from Martuni, Askeran, Shushi/a, and other areas, a local education ministry representative said.[38]

In Martakert town – where we also saw evidence of unlawful attacks on hospitals – School No. 1, with around 700 students, was hit on October 29 and on November 7.[39] All the windows were shattered, doors and window-frames were blown out, and walls and ceilings were cracked. “It’s an old building,” said the director, Roza Harutyunyan, pointing out the woodstoves.[40] “In some classrooms we were afraid the ceiling would collapse on our heads, so we can only teach in one part of the building. There is not enough space, and we now teach in two shifts.” The school had also been ransacked. “So much was stolen – pots and pans, furniture, a circular saw, an electric drill, a lawn mower,” said a staff member, who had heard where some of the items wound up. “Some things, well, they were taken by our military servicemen for their headquarters. I understand, they needed those things, but nothing has been returned. And some were stolen by local residents.”[41]

After the fighting, in late November, displaced people from areas handed over to Azerbaijan sheltered temporarily in the classrooms. They later moved out, and in January, long-planned repairs finally began on the school that had been suspended due to the fighting.[42] But there is another, longer-term challenge: Russian peacekeeping troops have set up a base at a sports stadium next door, including at least seven large tent-dormitories.

On January 20, Russian peacekeepers conducted military exercises across Nagorno-Karabakh, and in Martakert they neglected to warn the school. “Suddenly there was a horrendous noise, and children were running around and screaming that fighting had started again,” a staff member said. “An armored personnel carrier actually drove into the schoolyard. Soldiers were firing from assault rifles; all hell broke loose.”[43] Later, commanding officers said they would provide advance notice of maneuvers. They also gave the school a gift of glass windowpanes to replace the windows shattered by Azerbaijani shelling during the fighting, the staff member said. “It was a lot, enough for [us] to replace most of the broken windows. They have their own hospital at that base and they’re saying we can use it if we need it. But you know, with all the servicemen, their weapons, their equipment, some of the children are scared.”[44]

Martakert’s School No. 2 comprises three small buildings, built well over a century ago. One of them served as a military conscription point under the Tsar, with a basement garrison prison. Now, there is a gaping hole in the thick stone wall surrounding them, caused by a Grad rocket, according to a maintenance worker who said he found remnants of the munition. The damage from the explosion is consistent with a Grad attack: it caused the ceiling of one building to collapse; rain and snow ruined what was left inside. “That’s where we used to teach the first-graders, and [the building] had a library, a science lab and our gym,” said school director Melsida Kardumyan.[45]

The first-grade classes were moved, but the library, lab, and gym were lost. This school, too, had been looted. “All the equipment from the lab and the gym is gone, stolen. We no longer even have a skipping rope,” a staff member said. [46] By late February, most of the students and 22 newly-displaced children had enrolled, and another 35 former students were expected to return from Armenia. “They just won’t fit, so we will need to teach in two shifts. What we really need is a new school, with a bomb shelter. This one doesn’t have a reinforced basement,” Kardumyan said. Like many residents, she does not believe the ceasefire will be permanent.

Way Forward

Azerbaijan has allocated 2.2 billion manat (US $1.29bn) for reconstruction of the territories it took control over at the end of the six-week war, including an initial 7 million manat (US $4.1 m) to repair damaged schools. Azerbaijan’s education minister told us he hopes to partner with the international community to build “child-friendly cities.”[47] It remains to be seen whether the government of Azerbaijan, where a smaller proportion of today’s youth goes to university than their parents’ generation, can realize these high educational hopes. The area is contaminated with landmines and much of the infrastructure was razed. More than a quarter of landmine victims since the 1990s have been children.

Armenia and Azerbaijan should invite the deployment of an international, independent human rights monitoring presence in the areas affected by the conflict in 2020, to document human rights abuses and provide regular, public reporting on the human rights situation and emerging issues and risks. Armenia’s and Azerbaijan’s international partners should publicly call for the establishment of such a monitoring presence on the ground.As Azerbaijan and Armenia build and repair schools, both sides should commit to ensure that all children, including children with disabilities, have access to school this school year.

US military strategists are reportedly studying the role that off-the-shelf Turkish and Israeli unmanned aerial vehicles – drones – played in Azerbaijan’s battlefield success. Reports that drone strikes damaged schools and injured a child point to the need to study the battlefield failures that led to such a devastating impact on education.[48]

In Armenia, where the government received public criticism for the ceasefire deal but won June elections, the authorities should investigate, or at the very least acknowledge and seek to remedy, the military use and looting of schools. Armenia is one of almost 111 countries that have endorsed the Safe Schools Declaration, which upholds protections for education during armed conflict. The damage and destruction to scores of schools by mortars, heavy artillery shells, Grad and Smerch rockets, and ballistic missiles underlines the need to limit the use of explosive weapons with wide-area effects.

Azerbaijan should investigate all instances where its forces positioned military targets near schools. If its forces confiscated school records or other property in the areas where it took control, it should pass these to the authorities on the Armenian side. And it should endorse the Safe Schools Declaration.[49] The conflict and its aftermath – including skirmishes along the volatile new line of contact – show the need to strengthen commitments to the global norm of protecting education from attack.

Footnotes

[1] All references to local officials in Nagorno-Karabakh in this report should be read with the understanding that they represent the de facto authorities.

[2] Human Rights Watch interview, Yerevan, November 28, 2020.

[3] Letter from the Armenian ministries of Education, Justice, the human rights ombudsman of Armenia, and the human rights ombudsman of the Republic of Artsakh to Human Rights Watch, March 1, 2021..

[4] Ibid.

[5] Human Rights Watch interview, February 28, 2021.

[6] Human Rights Watch interview, Shikihakh, November 8, 2020.

[7] Human Rights Watch interview, Tartar, November 8, 2020.

[8] Human Rights Watch interview, Ganja, November 7, 2020.

[9] Human Rights Watch interview, Barda, November 9, 2020.

[10] Separate Human Rights Watch interviews with Guliyeva, Namig Suleymanov, and a local representative, Duyarli, November 8, 2020.

[11] Human Rights Watch interview, Duyarli, November 8, 2020.

[12] Human Rights Watch interview, Duyarli, November 8, 2020.

[13] Letter from the Armenian ministries of Education, Justice, the human rights ombudsman of Armenia, and the human rights ombudsman of the Republic of Artsakh to Human Rights Watch, March 1, 2021.

[14] Human Rights Watch interview with Raya Musayelyan, head of Education and Science Department, Artsakh Ministry of Education, Stepanakert, February 18, 2021.

[15] Human Rights Watch interview with a nurse practitioner, November 2020; observations from visit to Karmir Shuka; and interview with Raya Musayelyan, head of Education and Science Department, Artsakh Ministry of Education, Stepanakert, February 18, 2021.

[16] Human Rights Watch interview with the deputy director of School No. 29, Ganja, November 7, 2020.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Separate Human Rights Watch interviews with residents Yusif Ismayilov, Kamil Aliyev, and a local representative, Birinci Baharli, November 10, 2020.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Human Rights Watch interview with Mihran Jivanyan, at the time the director of School No. 2 and subsequently appointed a local Ministry of Education representative, Martuni, February 18, 2021.

[22] Letter from the Armenian ministries of Education, Justice, the human rights ombudsman of Armenia, and the human rights ombudsman of the Republic of Artsakh to Human Rights Watch, March 1, 2021.

[23] Human Rights Watch interviews with IPHR researchers, November 28, 2020.

[24] Human Rights Watch interview with Davit Mayilyan, Grigori Martirosyan, Rusanna Israyelyan, Department of Education, Askeran, February 19, 2021.

[25] Dates and times of attacks according to interview with astate official, Rovshan Garayev, Mahrizli, November, 2020.

[26] Letter from the Armenian ministries of Education, Justice, the human rights ombudsman of Armenia, and the human rights ombudsman of the Republic of Artsakh to Human Rights Watch, March 1, 2021.

[27] Ibid.; also, Human Rights Watch interview with local education ministry representatives, Stepanakert, Feb 18, 2021.

[28] Troops left School No. 1 between December 17 to 19. Human Rights Watch interview with a member of the school staff, Martuni, February 18, 2021.

[29] Human Rights Watch interview with a staff member of Martuni school No. 1, February 18, 2021.

[30] Human Rights Watch interview with Mihran Jivanyan, local Ministry of Education official, former director of School No. 2, Martuni, February 18, 2021.

[31] Letter from the Armenian ministries of Education, Justice, the human rights ombudsman of Armenia, and the human rights ombudsman of the Republic of Artsakh to Human Rights Watch, March 1, 2021.

[32] Human Rights Watch interview with Raya Musayelyan, head of Education and Science Department, Artsakh Ministry of Education, Stepanakert, February 18, 2021.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Human Rights Watch interview with Margarita Sahakyan, school director, Taghavard, Martuni District, February 20.

[35] Human Rights Watch interview with school staff, Taghavard, February 20.

[36] Human Rights Watch interview with Davit Mayilyan, Grigori Martirosyan, and Rusanna Israyelyan, Department of Education, Askeran, February 19, 2021.

[37] Human Rights Watch interview with Raya Musayelyan, Stepanakert, February 18, 2021.

[38] Human Rights Watch interview with David lalayan, Artsakh education ministry official, Martakert, February 19, 2021.

[39] Letter from the Armenian ministries of Education, Justice, the human rights ombudsman of Armenia, and the human rights ombudsman of the Republic of Artsakh to Human Rights Watch, March 1, 2021.

[40] Human Rights Watch interview with a staff member of School No. 1, Martakert, February 19, 2021.

[41] Human Rights Watch interview with a staff member of School No. 1, Martakert, February 19, 2021.

[42] Human Rights Watch interview with David lalayan, Artsakh education ministry official, Martakert, February 19, 2021.

[43] Human Rights Watch interview with a staff member of School No. 1, Martakert, February 19, 2021.

[44] Ibid.

[45] Human Rights Watch interview with Melsida Kardumyan, director of School No. 2, Martakert, February 19, 2021.

[46] Human Rights Watch interview with a staff member of School No. 2, Martakert, February 19, 2021.

[47] Human Rights Watch interview with Emin Amrullayev, Minister of Education of Azerbaijan, Baku, November 5, 2020.

[48] Letter from the Armenian ministries of Education, Justice, the human rights ombudsman of Armenia, and the human rights ombudsman of the Republic of Artsakh to Human Rights Watch, March 1, 2021.