The sounds of clapping, cheers, and banging pots and pans filled streets around the world on March evenings in 2020. From Italy to India, residents under lockdown came together to thank the “healthcare heroes” on the front lines of the Covid-19 pandemic response.

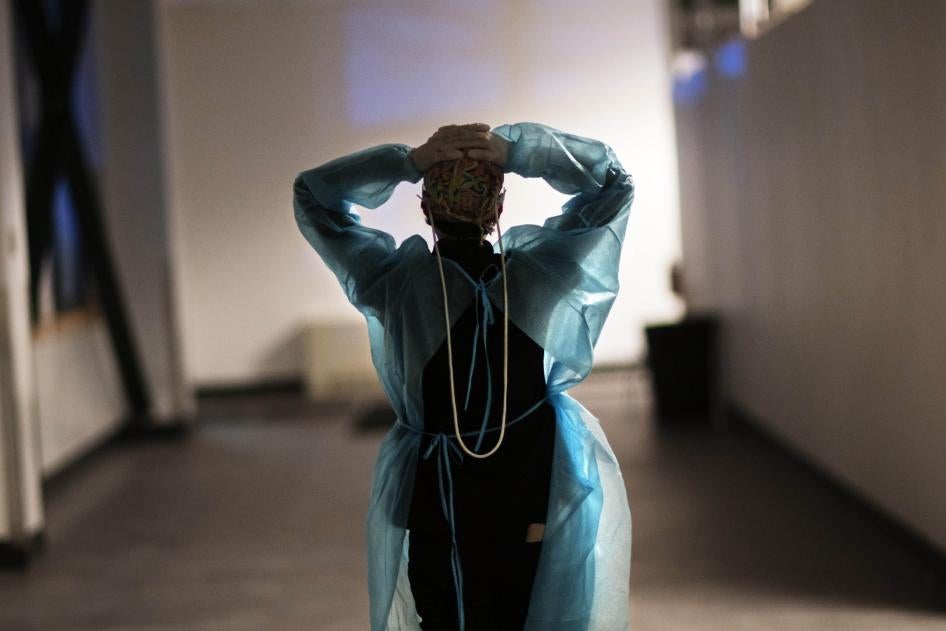

But inside health facilities worldwide, many workers’ lives were treated as dispensable. As they continue their lifesaving work, one year into the Covid-19 pandemic, public displays of gratitude devoid of action are not enough. It is incumbent upon us to transform our gratitude into solidarity, by calling upon governments and the private health sector to protect workers’ labor rights. They need occupational health and safety protection, paid sick leave, freedom from violence and harassment at work, and freedom of expression, during and beyond the current crisis.

At the most basic level, health workers have the right to adequate personal protective equipment (PPE) and instruction on its correct use. Health responders should be able to remove themselves from a work situation if their lives or health are put at unjustified risk.

And yet, despite their frequent, direct contact with Covid-19 patients, workers faced severe shortages of PPE and retaliation for speaking out against dangerous conditions. By September 2021, approximately 14 percent of Covid-19 cases reported to the World Health Organization were among health workers, though they constitute less than three percent of the population in most countries. While the data does not specify where infected health workers contracted the virus, insufficient PPE in the workplace placed them at great risk.

In a survey of 901 health workers in the United States—most in high-resource, urban or semi-urban health settings—conducted by Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) and UC Berkeley, 63 percent of respondents reported PPE shortages. Human Rights Watch interviewed six nursing home workers at different facilities in the US last March and April. They all reported that their supply of both surgical and N95 masks had been inadequate.

Sandy T., a Certified Nursing Assistant, reported that in March, workers were reusing the same mask throughout the work week and resorting to washing disposable gowns. She added: “There was not enough sanitizer, masks, and I had to clean myself with bleach. Last year was very stressful.”

In the Amur region of Russia, nurse’s aides working in a Covid-19 unit even resorted to reusing masks from the container where doctors would discard theirs. In multiple Russian cities, Human Rights Watch research revealed a disturbing pattern of inequitable distribution of PPE. While workers in ambulance brigades and “Covid-19 designated” hospitals benefitted from a steady supply, healthcare workers in other facilities who were regularly exposed to confirmed or suspected Covid-19 cases received no or insufficient protection.

In late March, Russian authorities amended the Criminal Code and introduced harsher penalties for “spreading false information”—creating additional risks for healthcare workers who spoke out about insufficient PPE.

From Russia to Nicaragua, governments the world over threatened or retaliated against medical workers for speaking out about dangerous workplace conditions or criticizing the government’s Covid-19 response.

A socio-healthcare worker in Italy, for example, told Human Rights Watch that, in the spring of 2020, his colleagues brought a class action against their facility’s cooperative and the foundation that manages it to address failures concerning the provision of PPE. Many of the workers involved in the class action faced reprisals, including a colleague who was fired after speaking to the media.

The Egyptian government of Abdel Fattah al-Sisi went as far as arresting at least nine medical professionals, accusing them of “spreading false news” and “misusing social media.”

In Burundi, the authorities initially downplayed the threat of Covid-19, and issued a statement in March threatening action against anyone who took “hasty, extreme, unilateral measures” ahead of the government to combat the virus.

Some hospital workers in Burundi told Human Rights Watch that their supervisors instructed them not to talk about suspected cases, symptom patterns, or insufficient resources. Healthcare workers in Burundi, and also in Uganda and Guinea, faced severe shortages of equipment, testing capabilities, and caregiving personnel for their patients, largely due to a chronic lack of government investment in the countries’ healthcare systems.

Notwithstanding the great personal sacrifices undertaken by healthcare workers and their families around the world, compensation was not always commensurate. In many cases, low-paid health workers faced the impossible choice between potentially exposing family members to a deadly virus or losing essential income. Women, who comprise 70 percent of the world’s health workforce, struggled to balance paid jobs with unpaid labor, including taking care of relatives.

A nursing home worker in the US told Human Rights Watch that she was torn over whether to continue to go to work and potentially risk the health of her mother and baby. Cutting back on hours was not an option, as she would lose her health insurance. Ultimately, financial pressures won out: “I need to pay the bills, but I don’t want to be in that building, I really don’t.”

Over the past year, healthcare workers have labored tirelessly to protect patients’ lives and health, often with insufficient means to fully protect their own. But many governments and private health facilities failed to take reasonable actions to uphold their responsibilities to protect healthcare workers’ rights to occupational safety and health.

Healthcare workers should not be made to indefinitely bear the brunt of a deadly pandemic without meaningful support from governments—many of which stalled in their action to curb the spread of Covid-19. It is a relief that healthcare workers are being prioritized for vaccination in many countries.

Governments should urgently address the huge inequities in vaccine distribution globally. But it is just as important for them to address the systemic issues that health workers have grappled with since the pandemic hit. Health workers are the backbone of the global Covid-19 response and will continue to be frontline defenders of people’s lives and health. As workers, they deserve equal protection of their rights. And as the recipients of their care, we owe it to health workers everywhere to stand up for their safety.

Laura Mills contributed reporting on US nursing homes and Fatima Burhan contributed reporting on Italy.