Introduction

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared that an outbreak of the viral disease Covid-19—first identified in late 2019 in Wuhan, China—had reached the level of a global pandemic. Citing concerns with “the alarming levels of spread and severity,” the WHO called on governments to take urgent and aggressive action to stop the spread of the virus.

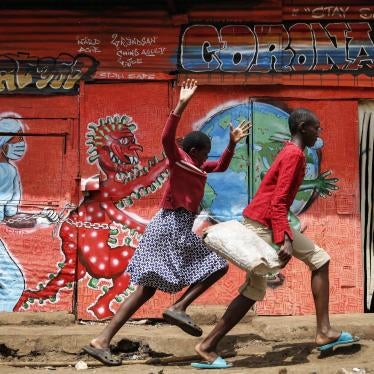

Over the next 12 months, a varied global response to an unprecedented public health crisis unfolded. Some governments were quick to impose lockdowns and travel bans, and implemented various strategies requiring or promoting practices such as universal mask wearing, social distancing, following the advice of emerging scientific knowledge, and models. Some governments were able to implement comprehensive emergency responses that sought to protect not only the right to health, but other rights such as an adequate standard of living including the rights to housing and water, as well as other forms of social protection. Others—most—struggled to respond to the challenges of the pandemic, while some indulged in denying the threat to people’s lives and health that Covid-19 posed, while also taking advantage of it to restrict rights including freedoms of speech, assembly, access to information, and political participation.

The right to the highest attainable standard of health under international law obligates governments to take steps to prevent threats to public health and to ensure access to medical care for those who need it. Human rights law also recognizes that in the context of serious public health threats and public emergencies, an effective response may require temporary restrictions on some rights. Such restrictions need to have a legal basis, be strictly necessary with a rational basis, proportionate to achieve the objective, and be neither arbitrary nor discriminatory in application. They should be of limited duration and subject to review.

The scale and severity of the Covid-19 pandemic rose to the level of a public health threat that justified some restrictions on certain rights. However, the pandemic has also been characterized by governments using public health emergency measures to grab power and abuse rights, the systematic neglect of some minority populations, and failures to anticipate and counteract ways in which harm resulting from the pandemic and measures to contain it fell disproportionately on people already facing inequity due to factors including race, gender, age, disability, and immigration or socioeconomic status. In April 2020, the United Nations secretary-general, António Guterres, said, “The public health crisis is fast becoming an economic and social crisis and a protection and human rights crisis rolled into one.” Indeed, in the months following Guterres’ statement, the world witnessed a cascade of abuses and failures to protect people as the virus infected at least 113 million people and killed more than 2.5 million people.

As vaccination efforts have begun in some countries, the promise of the scientific community’s extraordinary efforts is bearing fruit. By February 6, 2021, the WHO director-general, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, said that the number of vaccinations had overtaken the number of reported infections, but pointed out that “more than three quarters of those vaccinations are in just 10 countries that account for almost 60% of global GDP” and “almost 130 countries, with 2.5 billion people, are yet to administer a single dose.”

The question for the international community, for governments around the world, and for the multilateral institutions and corporations who hold the keys to a rights-respecting exit from the Covid-19 pandemic, is not whether it is technically possible, but rather whether they have the willingness to abide by their human rights commitments to make it happen.

Key Recommendations

As we enter the second year of a global pandemic, there are key actions governments should take to prevent further human rights backsliding and ensure an equitable exit from this global public health emergency. Governments should cooperate and develop strategies, including by regulating and holding companies accountable, to ensure universal and equitable access to Covid-19 vaccines.

Governments should protect the rights of healthcare workers and other essential workers, especially by bolstering occupational health and safety measures.

Measures to protect against the spread of the virus should be in line with international law. This means that when quarantines or lockdowns are imposed, for example, governments should ensure access to food, water, health care, education, support services for people with disabilities, and services for survivors of gender-based violence. Any tracking systems or other technologies used to implement public health measures should be transparent and subject to regular review and oversight. Governments should seek to combat the spread of misinformation on the pandemic while also protecting the right to freedom of expression, and ensuring that any restrictions on movement, assembly, or association are nondiscriminatory, limited in duration, and proportional to the public health threat.

Governments should protect older people, people with disabilities, people in detention, and others living in institutions and long-term care facilities from Covid-19, taking all feasible measure to decrease the risk of Covid-19 spread in congregate settings while avoiding blanket bans on visitors or outside monitors. The authorities should reduce the number of people in all detention facilities, including immigration detention, and they should facilitate the transfer of persons with disabilities from closed institutions into community-based settings. Governments should not impose sanctions for violating Covid-19 containment measures that are at odds with public health responses, such as incarcerating violators in conditions that increase risk of virus contraction.

Governments should ensure that economic recovery efforts emphasize protection of economic and social rights, including an adequate standard of living for all without discrimination, particularly for groups that were disproportionately impacted by Covid-19 or related lockdowns, and avoid austerity measures harmful to human rights. Instead, they should invest in quality services for all, including accessible and affordable health care, water and sanitation systems, education, and housing. Governments should immediately implement measures to ensure access to sufficient, affordable, and safe water for all as a critical matter of public health and human rights, and should ensure that household water and sanitation services are never cut for inability to pay, and provide economic support for a moratorium on evictions for inability to pay.

Scope and Methodology

Drawing on Human Rights Watch research conducted in at least 100 countries between March 2020 and February 2021, this report provides an overview of the human rights violations governments committed or allowed during the Covid-19 pandemic on a broad range of topics. While not exhaustive, the report illustrates disturbing trends Human Rights Watch documented around the world.

The report covers a range of research documenting the disproportionate impact of Covid-19 on certain marginalized groups, human rights concerns highlighted and exacerbated by the pandemic, and new issues brought to bear. Topics include the imperative of universal and equitable vaccine access; the right to adequate health care; the rights of healthcare workers, women, older people, people with disabilities, and people in detention; ensuring the right to education; addressing economic inequality in the Covid-19 response; Covid-19 and technology; protecting the rights to freedom of expression and assembly; implementing rights-respecting quarantines, lockdowns, and travel bans; and addressing Covid-19 in conflict and humanitarian emergencies.

The report is accompanied by essays on selected themes, including on vaccine access, women’s rights, healthcare workers’ rights, the use of technology in combating the pandemic, older people’s rights, China’s role in the pandemic, and how the pandemic impacted poverty and inequality globally, calling attention to urgent human rights issues brought to the fore by Covid-19 that should be addressed as we enter the second year of a global pandemic, as well as inspiration for a more just, equitable, and ultimately healthy post-pandemic world.

Failing on Universal and Equitable Vaccine Access

The Covid-19 pandemic is among the gravest global health and economic crises in recent history. By February 2021, nearly one year after the WHO declared it a pandemic, the virus had taken the lives of over 2.5 million people and infected at least another 110 million more, leaving many of them severely ill. As documented in this report, in other Human Rights Watch materials, and by numerous civil society organizations, human rights monitors, journalists, and other observers, its social and economic consequences have been widespread and devastating. Universal and equitable access to a safe and effective vaccine is critical to halting the spread of Covid-19.

By early 2021, several vaccines were found to be safe and effective, bringing hope that they could be used to prevent severe illness and death while protecting livelihoods and allowing battered economies to recover from the consequences of the pandemic. However, while scientists and researchers had risen to the occasion and developed vaccines at unprecedented speed, the behavior of many of the world’s richest countries significantly undermines universal, equitable, and affordable access to those vaccines.

Governments invested tens of billions of dollars of public funds in vaccine development, but when it came to meeting human rights obligations to share the benefits of scientific research partially funded with that public money, and to cooperate internationally to protect the rights to life, health, and an adequate standard of living, wealthy countries have fallen far short.

Throughout 2020, a movement of advocates, including Covid-19 survivors and loved ones of those who died, called for a “people’s vaccine.” And while the movement gained considerable support, many wealthier governments pursued a different strategy, negotiating opaque bilateral deals with pharmaceutical companies or other entities, reserving vaccine doses largely for the use of their own populations irrespective of greater medical needs in other countries, and walked back prior pledges to support a more equitable distribution framework.

The approach wealthy countries have taken to vaccine acquisition and distribution thus far has amounted to “vaccine nationalism,” the practice of secret deal-making and prebooking future vaccines when vaccines are widely projected to be in scarce supply, rather than cooperation. This significantly undermines universal, equitable, and affordable access.

The world has seen this before. Two decades ago, a similar fight was underway for equitable access to affordable HIV treatment. At the time, in the early 2000s, about 9,000 people a day were dying of AIDS, largely in countries where antiretroviral drugs were unavailable or unaffordable. It culminated in the 2001 Doha Declaration, negotiated by World Trade Organization (WTO) member states, which clarified that under global intellectual property rules, governments could issue licenses for patents during a public health crisis.

The governments of South Africa and India have led efforts at the WTO to promote more equitable access to Covid-19 medical products, including vaccines, by temporarily waiving some intellectual property rules. They propose that some provisions of the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) be waived, to allow all countries to collaborate with one another, without being confined to working within the complex legal framework and restrictions governing intellectual property. The proposal goes beyond the flexibility on licensing introduced by the Doha Declaration and gained the support of over 375 civil society organizations around the world. However, several high-income countries like the United States, Switzerland, United Kingdom, Australia, and Japan—some of which prebooked vast quantities of vaccine doses for their own populations—oppose the proposal, arguing that the Doha Declaration is sufficient.

Recommendations

Governments should:

- Cooperate to develop a strategy to fund and support the creation of additional manufacturing capacity where needed to meet vaccine demand, especially in low- and middle-income countries;

- Use their regulatory and funding powers to drive vaccine producers to share their intellectual property through technology transfers and global, open, and nonexclusive licenses;

- Pledge not to sign bilateral deals with vaccine developers or prebook future vaccine doses;

- Support efforts at the WTO to temporarily waive some provisions in the TRIPS Agreement as they relate to Covid-19 vaccine development.

Right to Adequate Health Care

The Covid-19 pandemic underscored structural weaknesses in public healthcare systems around the world, highlighting and further contributing to massive inequality in access to lifesaving care. Inequality continues to determine not only who gets sick, but whether they can access care. The pandemic laid bare the global cost of failing to provide universal access to basic health care, a cost already born disproportionately by marginalized populations.

People living in poor or Indigenous areas in Mexico, for instance, are 50 percent more likely to die of Covid-19 and less likely to have received intensive care. Black, Latinx, and Native communities in the US face increased risk of infection, serious illness, and death from Covid-19, disparities linked to longstanding inequities in health outcomes. In Brazil, Black people are more likely than other racial groups to contract the virus and to die in the hospital. Several European Union countries were criticized for not taking proportionate action to address the higher risk of death from Covid-19 in Roma communities.

Longstanding institutional barriers to health care left Indigenous peoples in many countries particularly vulnerable to complications from Covid-19. Those barriers faced by people with disabilities were only accentuated by the pandemic, especially for those who receive personal support for tasks of daily living.

While the right to health does not guarantee a right to be healthy, it guarantees the best possible state of health for the population, based on existing knowledge. As such, governments are obligated to provide a system of health protection that offers equality of opportunity for everyone to enjoy the highest attainable level of health and to enact policies promoting available, affordable, quality health services, without discrimination. This requires health facilities, goods, and services to be scientifically and medically appropriate and of good quality, including availability of skilled medical personnel, scientifically approved and unexpired drugs and hospital equipment, sufficient safe drinking water, and adequate sanitation.

In many countries, however, longstanding neglect for public healthcare systems left hospitals woefully unprepared to respond to the virus. In Hungary, for instance, Human Rights Watch found that poor conditions in public hospitals, including a lack of water, hand soap, sanitation supplies, and personal protective equipment (PPE) for health workers and patients, may have contributed to the spread of the virus in Hungary where 25 percent of reported confirmed infections were contracted in hospitals, and hospital-acquired Covid-19 infections led to almost 50 percent of reported deaths. In Greece, healthcare workers protested throughout the year against insufficient levels of staffing, medicines, testing, and equipment to treat Covid-19 in public hospitals. In Papua New Guinea, the Ministry of Health reported on Covid-19 preparedness detailing chronic deficiencies, as well as inadequate training on the use of PPE and infection prevention and control.

Venezuela’s collapsing health system was unprepared to provide adequate care for Covid-19 patients, but even prior to the pandemic, its failure, including severe water shortages, had led to the resurgence of other vaccine-preventable and infectious diseases. In Lebanon, the Covid-19 pandemic placed additional strain on a healthcare sector also already in crisis. The government’s failure to reimburse private and public hospitals more than one billion dollars in unpaid dues impacted the hospitals’ ability to provide patients with urgent and necessary medical care. In addition, a dollar scarcity in the country restricted the import of vital medical equipment, including ventilators and some PPE.

Failing public health infrastructure potentially fueled corruption in determining access to care, meaning whether someone lives or dies from Covid-19 in some places was determined by privilege. In Bangladesh, for example, where the healthcare system was overwhelmed by the Covid-19 pandemic, doctors told Human Rights Watch that they were having to turn away patients under pressure to reserve limited intensive care facilities for those with clout or influence.

Lack of resources to treat Covid-19 in already fragile public healthcare systems meant that medical care for other illnesses and preventive medicine risked falling by the wayside. According to a September UN report, hospitals and clinics in Afghanistan, for example, had little capacity to maintain essential services while treating patients with Covid-19, causing a 30 – 40 percent decline in people accessing health care. Again, this disproportionately impacts the lives of marginalized groups. Marginalized ethnic groups, such as Madhesis in Nepal, for example, are disproportionately suffering diminished access to clinical services. Millions of children in India, particularly those from Dalit and tribal communities, are at increased risk of malnutrition and illness during the pandemic because the government failed to adequately ensure the provision of meals, health care, and immunizations that many marginalized children rely on from the government schools and Anganwadi centers, which were closed in order to stop the spread of Covid-19.

Some governments, including those of Afghanistan, Papua New Guinea, and Bangladesh, suspended vaccine programs for preventable diseases. Because of insufficient PPE, the Afghan government suspended polio vaccinations of children. In Papua New Guinea, Covid-19 restrictions interrupted tuberculosis vaccine programs. In Bangladesh, measles vaccinations programs were halted in the Rohingya refugee camps.

Impact on Sexual and Reproductive Health Care

Many governments were quick to cut back on sexual and reproductive health care amid the pandemic. In doing so, they not only obstructed the right to health but jeopardized a range of human rights that cannot be realized without the ability to make decisions about one’s own body, including the right to education and the rights to equality and nondiscrimination.

The International Planned Parenthood Federation, a global nongovernmental organization that promotes sexual and reproductive health, reported that the pandemic forced the organization to close thousands of family planning facilities—either due to government orders, or social distancing needs. Colombia, El Salvador, Pakistan, Germany, Ghana, Malaysia, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe have each had to close at least 100 such facilities. In Papua New Guinea, where maternal mortality rates are among the highest in the Pacific region, failure to implement measures to ensure women and girls can safely access healthcare facilities amid the Covid-19 pandemic has made pregnancy even more unsafe. In Pakistan, where maternal mortality rates were already the highest in South Asia, authorities closed several major maternity wards after some staff members tested positive for the virus, exacerbating an already grim situation, especially for impoverished women and girls. In Venezuela, where hospitals were already in the grip of a humanitarian crisis, some maternal health centers suspended prenatal and postnatal services in 2020 due to the pandemic, and NGOs reported that pregnant women suspected of having Covid-19 were being denied prompt care. The United Nations Population Fund warned that the pandemic could leave 47 million women in low- and middle-income countries unable to avail of modern contraceptives, leading to a projected seven million additional unintended pregnancies.

While France, England, Spain, and Germany, among others, facilitated access to medical abortion (abortion induced through taking medication) in light of pandemic-related travel restrictions and the need to minimize hospital stays, women in several other countries reported increased difficulty in accessing safe and legal abortion during lockdowns. For example, some hospitals in Russia suspended provision of legal abortion during the pandemic and in Italy authorities did not immediately deem abortion essential health care with some facilities suspending abortion services or reassigning gynecological staff to Covid-19 care. The Italian Health Ministry clarified on March 30 that abortion services were nondeferrable, but hospitals and clinics did not always adhere to this guidance, and travel restrictions in place to stop the spread of Covid-19 exacerbated difficulties accessing abortion services that already come with burdensome requirements.

Some governments even used the pandemic as an excuse to further block access to abortion. In the US, 11 states have tried to limit access to abortion. In Brazil, the administration of President Jair Bolsonaro removed two public servants after they signed a technical note recommending that authorities maintain sexual and reproductive health services during the Covid-19 pandemic, including “safe abortion in the cases permitted by Brazilian law.”

Recommendations

Governments should:

- Invest in public healthcare systems so that they are accessible and affordable to everyone without discrimination, including marginalized groups. This is critical not only for responding effectively and adequately to the pandemic as it continues to unfold, but to ensure healthcare systems can provide care and prevent illness beyond Covid-19;

- Take all feasible steps to remove financial barriers to public health care and ensure that public healthcare services are not only available in sufficient quantity, but also are of good quality;

- Invest in increasing the availability of skilled medical personnel, ensuring affordable access to essential medicines, and ensuring that all public health centers have scientifically approved equipment, sufficient safe drinking water, and adequate sanitation and hygiene to protect the health of healthcare workers and patients;

- Recognize that sexual and reproductive health services are always essential and should not use the Covid-19 pandemic as an excuse to roll back access to reproductive health care or other services. As new lockdown measures may be enforced as the pandemic continues, governments should ensure that women and girls have access at all times to safe abortion services, prenatal and postnatal health care, and maternal health services;

- Ensure that family planning centers have the resources they need in order to stay open, including adequate provision of contraceptives, and that community members are able to access these centers without interruption. Any lockdown measures should explicitly identify reproductive health services as “essential” and ensure that people can safely access them;

- Following WHO guidelines, set the legal time frame for medical abortion at 12 weeks and eliminate requirements for hospitalization, instead providing guidance on self-management of medical abortion with in-person or telemedicine consultations.

The Plight of Healthcare Workers

Around the world, healthcare workers, the majority of whom are women, faced serious risks to their health and safety during the Covid-19 pandemic. Thousands of health workers have died. Tracking death and infection rates among health workers is difficult to do unless countries disaggregate and publish such data.

Particularly in the early stages of the pandemic, healthcare workers often did not have sufficient PPE, including masks, gowns, gloves, and eye protection, leading to high rates of infection and death. In Spain, for instance, organizations representing medical and care workers complained of ineffective, insufficient PPE in March and April 2020, with many forced to rely on homemade masks and gowns during the early weeks of the pandemic. In Syria, government authorities failed to protect healthcare workers in government-held territory. Healthcare workers reported serious shortages of PPE, and restricted access to oxygen tanks, which likely contributed to a high rate of death among health workers after suffering Covid-19 symptoms.

Many countries, including the US, Greece, Venezuela, Italy, Hungary, Bolivia, and Afghanistan experienced severe shortages of equipment and dangerous working conditions for healthcare workers.

In many countries such as Egypt and Bangladesh, healthcare workers became frontline sources of information about conditions in hospitals or the spread of Covid-19 more generally. They were retaliated against by governments and by employers for speaking out about inadequate PPE and other issues. In Egypt, the Interior Ministry in June 2020 forced the doctors’ syndicate members to cancel a press conference about government harassment of doctors in connection with Covid-19. Between March and June 2020, authorities arrested at least nine healthcare workers who challenged the official narrative on the pandemic or criticized lack of equipment at their workplaces. In Bangladesh, the government silenced healthcare workers who spoke out over a lack of PPE and resources for treating Covid-19.

In Nicaragua, between June and August 2020 the government fired at least 31 doctors from public hospitals in apparent retaliation for voicing concerns over the government’s management of the Covid-19 pandemic. In Russia, healthcare workers faced shortages of PPE, particularly in the first months of the pandemic. In some cases, those who spoke out about the shortages faced harassment and retaliation, including losing their jobs and/or facing charges of spreading false information. In Lebanon, major funding gaps in the healthcare sector, as well as the significant depreciation of the national currency reduced the value of healthcare workers’ salaries by almost 80 percent and restricted hospitals’ ability to maintain sufficient staffing levels and purchase PPE. Healthcare workers have become targets of violent attacks by patients and their families, especially as hospitals were no longer able to admit new patients. Since the start of the pandemic, there has been at least one serious attack on a doctor every month. In Guatemala and in the Democratic Republic of Congo, doctors and healthcare workers also reported delays in salary payments and a lack of PPE.

Recommendations

All governments have an obligation to protect the labor rights of health workers including by:

- Providing paid sick leave;

- Minimizing the risk of occupational accidents and diseases, through providing healthcare workers with training in infection control and with appropriate personal protective gear, and access to safe and effective grievance mechanisms with antiretaliation protection;

- Ensuring that compensation and other relevant social protection programs are in place for families of workers who died or became ill as a result of their work during the Covid-19 pandemic;

- Not engaging in and protecting healthcare workers against retaliation for speaking out about working conditions;

- Protecting health workers—in law and practice—against all forms of violence and harassment in the world of work, including from employers and the public.

Failure to Protect Older People and People with Disabilities in Institutions

Covid-19 has had a devastating impact on people living in residential institutions for older people and people with disabilities. Older people and people with underlying health conditions are more likely to have severe complications or die from the disease, and the virus can spread rapidly in communal settings, particularly when there is inadequate infection control. People in these institutions were also affected by visitor bans implemented in response to the virus. While limiting in-person interactions was important to protect the health of residents and staff members, the blanket nature of these bans negatively impacted residents’ physical and mental health and led to an overall decrease in transparency around governance of such institutions.

In the US, for example, approximately 40 percent of state-reported Covid-19 deaths and six percent of cases were among people living in long-term care institutions. Nursing facilities’ longstanding infection control deficiencies and reduced public oversight of nursing homes during the Covid-19 pandemic likely put older residents at greater risk. Nursing home operators pushed state and federal governments to give them broad legal immunity during the pandemic.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the regulator for US nursing homes, announced a “no visitors” policy in March in response to the pandemic, with limited exceptions for end-of-life visits, cutting residents off from families, friends, and independent monitors. In normal times, visitors often supplement care by staff, advocate on residents’ behalf, and provide essential emotional support. CMS updated its guidance in September to allow for visitation in some circumstances, though protocols varied widely across states. Short-staffing, long a problem in US nursing homes, became particularly acute during the pandemic. Media reported numerous cases of alleged neglect of nursing home residents during this time.

Covid-19 had a similarly disproportionate impact on care facilities in countries such as Italy and the UK, where concerns arose around whether the government acted swiftly enough to protect the rights to life and health of residents. In Australia, there were hundreds of deaths in aged care homes, with some experts saying many of the outbreaks were preventable. The pandemic shone a light on insufficient staffing and inadequate community-based models of care. The government announced restrictions on visits to nursing homes, and some facilities banned visitors altogether.

In some countries, governments did not publish timely or transparent information about Covid-19 outbreaks in nursing homes or institutions for people with disabilities. For example, in Russia, the government did not publish regular statistics about rates of infection or death from Covid-19 in closed institutions. Similarly, in Serbia there was no data on the number of people with disabilities in residential institutions that died of complications from Covid-19, and in Brazil the lack of centralized data made it nearly impossible to assess the impact of the virus in care institutions.

For some people with psychosocial disabilities (mental health conditions) who in many countries are chained in homes or overcrowded institutions without proper access to sanitation, running water, soap, or even basic health care, Covid-19 is an extreme threat. In many countries, Covid-19 has disrupted basic services and psychosocial support, leading to people with psychosocial disabilities being shackled—chained or confined in small spaces—for the very first time or returning to life in chains after having been released.

Covid-19 response plans often overlooked people with disabilities. In Lebanon, for example, people with disabilities were not consulted in preparing the government’s emergency response plans and are facing barriers in accessing health care.

Recommendations

Governments should:

- Ban chaining and move to transfer people with disabilities out of closed institutions where safe to do so and stop new admissions;

- Provide older people and people with disabilities with support and services to live in the community.

People in Detention

People in prisons, jails, and immigration detention are frequently held in overcrowded and cramped conditions without adequate sanitation and hygiene, or access to adequate medical care, putting millions of imprisoned people worldwide at severely increased risk of contracting Covid-19. Some of the worst outbreaks have been in places of detention.

Despite obligations under international human rights law to ensure that prisoners have access to at least equivalent health care as the general population, people in detention frequently do not receive adequate health care even under normal circumstances. This pattern continued when prison authorities failed to implement adequate health and safety measures in response to Covid-19. In a US prison in April 2020, for instance, staff did not wear masks and lacked cleaning equipment, fresh clothes, and soap. In Mexico and Eritrea, the suspension of family visits in response to the pandemic meant that detainees who relied on visitors to bring necessities that should have been provided by authorities were left without soap and other hygiene supplies. In Cambodia, where prisons are severely over-capacity, people in custody have limited access to water, soap, and hand sanitizer, and are held in extremely close quarters. Prisoners in Colombia, Venezuela, Argentina, Bolivia, Italy, and Greece protested their governments’ failure to adequately address the spread of the virus in detention centers.

In addition to already overcrowded conditions, some authorities forced prisoners into cramped cell blocks for counting or other measures, without precautions and in complete disregard for health guidance on social distancing. In El Salvador, for instance, when President Nayib Bukele declared a “state of emergency” in maximum security prisons, official photographs and videos showed thousands of mostly-naked detainees—few wearing face masks—jammed together on cellblock floors while police searched cells, further exacerbating the already heightened risk of contagion. In Cuba, government critics were repeatedly detained in unsanitary and overcrowded cells conducive to the spread of Covid-19. Indian authorities ignored appeals to release detained activists, and several contracted Covid-19 in detention.

In some cases, authorities subjected prisoners to solitary confinement under the pretext of protecting against the spread of Covid-19. Several prisons and youth detention centers in Australia implemented long periods of lockdown and extreme isolation, with conditions reportedly akin to solitary confinement. Detainees in a US prison said that staff ignored people who said they were sick or placed them in punitive solitary confinement.

In at least 125 countries, prisons are overcrowded at the time the virus emerged, further escalating the danger of contagion. A major factor contributing to this overcrowding is the large percentage of people being detained while awaiting trial in many countries, in violation of international norms. For instance, according to official data collected by the Institute for Crime and Justice Policy Research, a policy-oriented academic research group, in Bangladesh and Gabon, over 80 percent of people in detention are awaiting trial; in Paraguay, Benin, Liechtenstein, the Philippines, and Haiti over 75 percent; in Switzerland and Luxembourg, over 40 percent.

In order to protect against the spread of the virus, some countries initiated releases of imprisoned people, including the US, Honduras, Haiti, Ecuador, Cuba, Bangladesh, Brazil, Chile, Argentina, Colombia, Afghanistan, Angola, Burkina Faso, Iraq, France, Mali, Congo, Pakistan, Zimbabwe, and Italy. In Libya, the Tripoli-based Government of National Accord announced the release of 466 pretrial detainees as well as detainees who met the rules for conditional release from prisons in Tripoli in order to reduce overcrowding and mitigate a Covid-19 outbreak. Many of these releases, however, did not include children, excluded people awaiting trial, and were minimal compared to the overall prison population. Many countries lagged behind implementing announced releases.

Releases in some countries specifically excluded human rights defenders and others wrongfully imprisoned for peacefully exercising their rights to freedom of expression, assembly, and association. For instance, In Algeria, President Abdelmadjid Tebboune signed a decree pardoning 5,037 people, but excluded activists and human rights defenders of the Hirak movement, a popular uprising demanding regime reform, as well as political and socioeconomic rights. In Syria, where the government has arbitrarily arrested and forcibly disappeared thousands since the start of the conflict for their participation in peaceful protests or for expressing political dissent, small-scale releases have failed to include human rights defenders and activists.

Although Bahrain released 1,486 people from prison in March 2020, the releases systematically excluded opposition leaders, activists, journalists, and human rights defenders—many of whom are older and/or suffer from underlying medical conditions. In Cameroon, an April 2020 presidential decree providing for the release of prisoners to prevent the spread of Covid-19 in overcrowded jails did not include suspected Anglophone separatists arrested as part of the ongoing crisis in the northwest and southwest regions.

Despite urgent calls for his release due to the heightened risk to his health because of the Covid-19 pandemic, Kyrgyz authorities took no action to release the wrongfully imprisoned human rights defender Azimjon Askarov. In July, as Covid-19 cases were surging in Kyrgyzstan, Askarov died in custody of pneumonia.

Authorities in some countries detained people for violating curfews, quarantines, or other restrictions in place to stop the spread of Covid-19, adding to the number of people in custody and paradoxically increasing the risk of contracting the coronavirus in overcrowded cells, detention centers, and prisons. In Angola, police released data showing that almost 300 people had been detained in just 24 hours for violating state of emergency rules. In addition to arresting health workers and critics, Egyptian authorities reportedly arrested thousands for breaking the nighttime curfew imposed from late March to late June 2020. Rwandan police arrested over 70,000 people for infractions related to pandemic measures.

Migrants were in especially precarious positions during the pandemic, as deportation was often suspended or restricted, leaving them stuck, often in densely crowded facilities, without due process or resolution of the reason for their detention. Deaths in US immigration detention spiked to a 15-year high with at least eight fatalities related to Covid-19. Though some detainees were released in response to the pandemic, as of February 2021, more than 9,000 people had contracted Covid-19 while in immigration detention in the US. When border closures forced the Mexican government to suspend deportations to Central American countries, detainees protested at five migrant detention centers demanding to be released over fears that overcrowding and unhygienic conditions put them at increased risk of contracting Covid-19. Later, Mexico’s National Human Rights Commission found that the government had held migrants who had tested positive for Covid-19 in the same space as others with no symptoms without providing facemasks, soap, electricity, or running water, and in one case had failed to provide appropriate medical attention to a migrant who later died of Covid-19. After people held in immigration detention in Canada went on a hunger strike to protest the lack of protection from Covid-19 in detention facilities, the government released people at unprecedented rates. A Saudi deportation center in Riyadh continues to hold hundreds of mostly Ethiopian migrant workers in conditions so degrading that they amount to ill-treatment. Detainees alleged to Human Rights Watch that they are held in extremely overcrowded rooms for extended periods, and that guards have tortured and beaten them with rubber-coated metal rods, leading to at least three allegations of deaths in custody between October and November. In the Maldives, when migrant workers protested unpaid wages and lack of access to food and other essential supplies due to the lockdown, the authorities called them a threat to national security and detained several in crowded facilities.

Authorities in some European Union countries, including Spain and Belgium, ordered people released from immigration detention, while legal challenges in numerous other EU countries forced authorities to release people given the health concerns and the lack of any reasonable prospect to deport.

Recommendations

Governments should:

- Implement and expand promised release orders to protect against the spread of Covid-19 in detention centers. Release orders should include children and people at elevated risk from the virus due to age or underlying health conditions, as well as people awaiting trial, migrants and asylum seekers, and people with caregiving responsibilities, unless their release poses a serious and concrete risk to others. Release orders should not exclude human rights activists and journalists, including those in detention for criticizing the government’s response to Covid-19;

- Cease all arbitrary detentions of migrants, seek alternatives to detention for people currently in immigration detention, opting for release where possible, particularly for those in high-risk categories if infected, and for people who are being held with no prospect for imminent, safe, and legal deportation;

- Implement protective measures in detention settings that include screening and testing for Covid-19 according to the most recent recommendations of health authorities; providing adequate hygiene, sanitary conditions, and medical services; and reducing density to allow social distancing and to allow placing all who are ill or their close contacts in nonpunitive isolation or quarantine, with access to appropriate medical care;

- Cease incarcerating people for violating Covid-19 containment measures, and do not hold any detainees in conditions that increase risk of virus contraction;

- Ensure transparency in monitoring and reporting on transmission of Covid-19 and other illnesses in detention centers and report publicly on what measures are being taken to protect the physical and mental health of all people in detention.

Gender-Based Violence

Reported cases of gender-based violence, particularly domestic violence against women and girls, increased worldwide amid the pandemic, particularly during lockdowns implemented to stop the spread of the virus. Domestic violence helplines across Pakistan, for example, recorded a 200 percent increase in cases from January to March 2020, and became worse after lockdowns were implemented. In Italy, Indonesia and Russia, service providers and women’s groups reported that calls to domestic violence helplines at least doubled amid lockdowns. Calls to the national gender-based violence helpline in Spain went up by over 60 percent in April 2020.

In France and Japan, reports of domestic violence rose by about 30 percent during the countries’ respective lockdowns. In Brazil, data from a government hotline indicated that the pandemic had brought a significant daily increase in rights violations against older people, including mistreatment, and people working on domestic violence confirmed a rise in violence against older women by their partners, children, or caregivers.

This uptick in violence against women and girls highlights preexisting gaps in government measures to prevent violence and to provide comprehensive services for women and girls seeking to escape or recover from violence. In Armenia, before the pandemic, many women and girls were already trapped in a violent home because the country only has two domestic violence shelters with a total capacity for 17 – 20 people. This meant that when calls to an Armenian domestic violence helpline increased by 50 percent during the pandemic, there was nowhere for survivors to go.

Still, in many countries, already limited shelters, crisis centers, and other critical social services were deemed “nonessential” during lockdowns and governments often did not take measures to ensure survivors were able to access services and legal recourse. Mozambique, South Africa, and Zimbabwe were among the many countries that failed to plan for how survivors of gender-based violence would access services during lockdowns. In a telling example, while women’s groups in Morocco and Brazil reported an increase in domestic violence during lockdown months, the number of complaints to the authorities and prosecutions decreased, indicating that survivors faced serious obstacles to seeking help or legal recourse.

The Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan governments did not classify domestic violence services as “essential,” and closed shelters, crisis centers, and other services to newcomers. One activist in Kyrgyzstan explained that after reporting a domestic violence case, the police would just “take them both back home afterwards to be locked down again.” During a lockdown in the Rohingya refugee camps in Bangladesh, the government reduced access for humanitarian workers by 80 percent and restricted services and facilities, cutting off all protection services for women and girls, including gender-based violence case management.

Older women and women with disabilities also faced additional barriers to accessing already limited services during the pandemic. Many women living in residential institutions face risk of neglect, abuse, and inadequate health care, but also restrictions on their legal capacity, which take away their rights to make decisions for themselves. As recent Human Rights Watch research in Mexico demonstrates, women with disabilities may be at particular risk of domestic violence when they rely on family members for support in daily tasks and for basic needs, such as housing, food, and hygiene.

Domestic workers were at heightened risk as they were locked down with their employers. Women who are migrant domestic workers were particularly at risk and sometimes left stranded unable to get back to their country. Sex workers faced heightened risk as they struggled to survive an occupation where social distancing is especially difficult.

The internet can facilitate access to survivor support groups, counseling, health information, and other online resources that can be critical lifelines to women experiencing gender-based violence, but nearly half the world does not have access to the internet and, in low- and middle-income countries, over 300 million fewer women than men are online. The digital divide in all countries disproportionately leaves women from marginalized communities behind. In one example, service providers who respond to gender-based violence in the UK told Human Rights Watch that as resources go digital, the Covid-19 crisis has exacerbated a lack of access to specialist domestic abuse services for migrant and Black, Asian, and minority ethnic women.

Internet blackouts amid the pandemic further isolated survivors and cut them off from support services. Women’s rights activists in the Rohingya refugee camps in Bangladesh said they received increasing domestic violence and sexual abuse reports, but there was nothing they could do amid an internet shutdown that left aid workers unable to remotely coordinate support and protection services. One protection team member said that without officers working in the camps during the internet shutdown, “now if a woman is raped, that news will not reach me and she will not get any support from us.”

Some countries responded quickly to the alarming uptick in violence. The Australian government in July committed more than A$3 million (US$2.1 million) in additional funding to service providers and announced a new emergency accommodation program for survivors. The Italian government exempted women and children fleeing abuse from lockdown restrictions on movement and ordered local authorities to requisition vacant buildings to accommodate them if shelters were full. In Spain, the Equality Ministry in March launched a plan to tackle gender-based violence during lockdown, including reinforcing staffing for helplines and setting up a new instant alert system to report domestic violence, and judicial authorities kept courts open to hear cases relating to domestic violence and child abuse. Tunisia opened a new shelter for female victims of domestic abuse, extended the hours of operation of the shelter’s helpline, and introduced remote mental health assistance helpline in support of families.

As the world enters the second year of a global pandemic, governments have the responsibility to better monitor rates of reported violence against women and girls, implement interventions to prevent violence, and ensure services are accessible.

Recommendations

Governments should:

- Run ongoing public awareness campaigns explaining how people experiencing gender-based violence including domestic violence can access services;

- Ensure that services are available to all survivors of gender-based violence and domestic violence, including older people, those with disabilities, and those living in areas under movement restrictions or under quarantine and those infected with Covid-19;

- Expand outreach to ensure that, as more services move online during Covid-19 lockdowns, women without access to safe, private internet or mobile resources can continue to access services.

Disruption of Education

In an effort to slow the spread of the coronavirus, governments around the world closed schools: in April 2020, an estimated 1.4 billion students (90 percent of school aged children) were physically displaced from their preprimary, primary, and secondary schools in 192 countries.

In September, when roughly half of countries begin a new school year, 872 million students—half of the world’s student population—were physically outside of their schools, of whom at least 463 million still had no access to any form of distance education.

Hundreds of millions of students experienced a dramatic shift to distance learning, using worksheets, radios, televisions, cellphones, and computers. This resulted in an overwhelming dependence and need for affordable, reliable connectivity, devices that met learning needs, and the capability to use these technologies safely and confidently. But many children did not have the opportunity, tools, or access needed.

As a result, school closures did not affect all children equally. The pandemic exacerbated digital divides between children with access to these technologies and the opportunities they can provide, and those without. Children from the poorest families or from marginalized communities, living in rural areas, girls, and children with disabilities were more likely to be shut out of learning.

Some governments ended school altogether: in August 2020, Bolivia cancelled the rest of the school year, leaving almost three million children without education, and only partially reopened when the new school year began in February 2021. In mid-2020, Human Rights Watch interviewed parents and children in Cambodia, Central African Republic, Congo, Iraq, and Thailand, who said their children had been attending schools that, once the pandemic broke out, provided no education for months.

Others provided varying types and degrees of resources to help students, teachers, and families with the challenges of remote learning. Japan’s education ministry reported in April 2020 that only five percent of public schools provided live, interactive online education when schools closed, causing many children to study by themselves at home using textbooks and other paper materials. Singapore, by contrast, loaned laptops to more than 12,000 students who needed them for online learning.

In most places, the digital divide was severely exacerbated by school closures. These inequalities were evident in both developed and developing countries, and were compounded by gender. According to the International Telecommunications Union, in 2019, 48 percent of women used the internet globally compared to 58 percent of men. This can be understood in relative terms as a 17 percent global internet user gap. In a study across 10 countries in Africa, Asia, and South America, the UN Broadband Commission found women were 30-50 percent less likely than men to use the internet to participate in public life. Worldwide about 327 million fewer women and girls have a smartphone than men and boys.

For example, Chile created an online platform for students to access educational content. But only 27 percent of low-income households have access to online education, compared to 89 percent of high-income households. In Mexico, a lack of affordable internet access leaves many children, especially those in low-income households and children with disabilities, without access to education. Some people in rural, often Indigenous areas, have been unable to participate at all. In Honduras, just 18 percent of the population has home internet access; a quarter of homes in rural areas do not have electricity.

A study published in April reported that nearly half of teachers in rural areas had not been able to contact the majority of their students. Children from low-income households in Germany, including refugee children, often lacked equipment and an internet connection to participate in online lessons. Options for distance education are extremely low in Afghanistan, as only 14 percent of Afghans have access to the internet. Many parents cannot help their children study as only about 30 percent of women and 55 percent of men are literate.

Some governments attempted to accommodate students with disabilities or from marginalized backgrounds. For example, in Cuba, the government provided some televised classes in sign language for children who are deaf or hard of hearing. In other places, these students were left out of education. For example, Lebanon’s distance learning strategy was not implemented consistently in “second shift” classes, attended by Syrian children, leaving the majority “completely out of learning.” Children with disabilities have also been disadvantaged by Lebanon’s school and institution closures since February 2020 that have mandated online or remote learning without accommodating the needs of children with disabilities. Similarly, the vast majority of migrant children in Greece who live in camps were unable to access education during pandemic lockdowns. And while around 70 percent of Jordanian children had internet access, that figure drops sharply for refugees and poorer and marginalized Jordanians. The transition to remote learning has increased the risk that some children, particularly the most vulnerable, will not come back once schools reopen.

In some countries, fragile preexisting issues worsened during the pandemic. In Iraq, children living in poverty and displaced families were most disadvantaged, as most lacked access to digital learning options. The loss of education during the pandemic had a more dramatic impact on the many children who had lost three academic years preceding it when living under the Islamic State (also known as ISIS). Girls, out of school, faced heightened risk of gender-based violence and being forced into child marriage which is often driven by financial stress. UNFPA estimated that the impact of the pandemic, including economic hardships in its wake, could lead to 13 million additional child marriages over the next 10 years. Girls who are out of school are also more likely to face sexual violence and to become pregnant. All these factors make it less likely they will make it back to school.

A predictable and dire consequence of school closures is that children’s learning slowed and regressed. For many, it brought an end to their education. However, the negative consequences for children were not just limited to their academics: many children also felt social isolation, anxiety, stress, sadness, and depression. Others felt the loss of their autonomy. Where governments previously used schools to deliver nutrition and health support, access to these wellbeing services by children was also often hampered by school closures. For example, in India—where school closures affected more than 280 million students—government schools in many states did not deliver education at all during the lockdown, putting children from marginalized communities such as Dalit, tribal, and Muslims at greater risk of dropping out and being pushed into child labor and early marriage. In Russia, more than one third of schoolchildren reported experiencing depression due to self-isolation and distance learning, according to an official survey of primary and secondary school students.

Recommendations

While schools are closed governments should:

- Adopt measures to mitigate the disproportionate effects on children who already experience barriers to education, or who are marginalized for various reasons—including girls, those with disabilities, those affected by their location, their family situation, and other inequalities;

- Adopt strategies that support all students through closures—for example, monitoring students most at risk and ensuring students receive printed or online materials on time, with particular attention provided to students with disabilities who may require adapted, accessible material;

- Explore options to provide all students access to affordable, reliable internet service, as well as smart devices, recognizing that digital literacy and access to the internet are increasingly indispensable for children to realize their right to education.

When schools reopen governments should:

- Monitor compliance with compulsory education and school returns and reach out to reengage students who do not return;

- Carry out national “back to school” communications and mass outreach campaigns to persuade children who have been out of school—either due to the pandemic or other reasons—to return to school. Education officials should focus attention on areas with high incidence of child labor or child marriage and ensure all children return to school;

- Support schools with refugee students to adopt outreach measures to ensure refugee children return to school, including by working with refugee parent groups and community leaders;

- Offer support to help students return including help catching up, flexibility in meeting school requirements, childcare for students who are parenting, and financial assistance for students facing economic barriers.

Economic, Social, and Workers’ Rights During the Pandemic

Economic Relief

In efforts to contain the Covid-19 pandemic, many governments implemented public health measures such as social distancing, quarantine, and the mandatory closure of businesses, all of which had an enormous economic impact. Low-income workers, many of whom work in fields like retail, restaurants, and the informal sector, and are unable to work remotely, were disproportionately impacted by these measures and lost employment in larger numbers. Women were disproportionately likely to lose their jobs, driving a UN projection that the pandemic would push 47 million more women into poverty. The pandemic also caused disruptions to the global supply chain, leading to reduced manufacturing and factory closures. Poverty increased during the pandemic globally and may continue increasing, further entrenching preexisting inequalities.

In response to the economic crisis, many governments passed substantial financial spending measures to allow for the disbursement of periodic cash payments, enhanced unemployment benefits, and food aid.

Reliance on emergency food aid—a key indicator of poverty—rose across the EU during the year. National food bank networks in Greece, Spain, and in regions of Italy reported increases of 50 percent or more throughout the pandemic. In April and May, the European Commission increased resources to and announced measures to allow the Fund for European Aid to the Most Deprived (FEAD)—an emergency fund allowing the distribution of food, clothing, and sanitary items and programs for economic reintegration—respond faster to the crisis. The European Commission allowed member states more flexibility to deploy resources to tackle the economic fallout of the pandemic, created a €100 billion ($117 billion) fund to help states preserve employment and provided €750 billion ($909 billion) “to help repair the immediate economic and social damage.”

In the US, increased unemployment protection and direct payments in relief packages that were passed by Congress in March 2020 successfully halted an increase in poverty in the first months of the pandemic. However, as many protections expired in July and August, millions fell into poverty. While employment largely rebounded for higher-income workers, low-income workers continued to face significant job losses one year into the pandemic.

In many countries, government responses to the economic fallout of the pandemic did not protect basic economic and social rights. In addition, many governments provided inadequate transparency and oversight over their Covid-19 spending, making it difficult for the public to monitor these funds and enabling corruption or capture by wealthy individuals and corporations. In Cameroon, the government did not publish information on an emergency reserve use for Covid-19 and managed funds collected to respond to the pandemic in secrecy, obstructing the public’s ability to track public resources.

In Kazakhstan, where the social protection system was weak before the pandemic, the government took inadequate measures to counter the economic turndown and protect people who had lost jobs during the pandemic. Financial relief was lower than a monthly living wage needed to protect basic expenses. In Nigeria, government economic assistance left many still struggling to afford food and other necessities. The World Bank projected in June 2020 that the economic fallout from the pandemic would push five million more Nigerians into poverty. In Uganda, food assistance was planned for 1.5 million people, though more than nine million Ugandans live in poverty, and assistance was restricted to specific urban areas. In Spain, a scheme to support people living in poverty was soon overwhelmed, causing the government to extend the deadline for retrospective claims. In Lebanon, the Covid-19 pandemic exacerbated the already devastating economic crisis and exposed the inadequacies of the existing social protection schemes. The government failed to put in place a coordinated, robust plan to provide assistance. The government announced plans to provide food assistance that it has not carried out and has repeatedly delayed promised financial relief.

According to the UN, the poverty rate in Lebanon has doubled over the past year, and more than half the population now lives under the poverty line. The Covid-19 pandemic sparked an economic crisis in Cambodia, in which hundreds of thousands of people were suspended from work with little or no pay or were laid off outright. Many Cambodians have taken out microloans, often using land titles as collateral, but without jobs or income, they are unable to repay the loans. The Cambodian government and microloan providers have done little to respond to this microloan debt crisis, leaving hundreds of thousands of borrowers facing serious financial burdens without debt relief or loan restructuring that could alleviate that burden.

Marginalized groups, particularly those who worked in the informal sector, were sometimes excluded from financial support efforts. The South African government’s Covid-19 aid programs, including food parcels, overlooked people with disabilities, refugees and asylum seekers, sex workers, and LGBT people. Similarly, in Georgia, transgender people who work in the informal sector were excluded from a $1.5 billion plan to respond to the economic crisis. In the US, relief bills excluded informal workers such as street vendors and some immigrants, including all undocumented workers. In Thailand, migrant workers were excluded from financial support.

Workers’ Rights

The pandemic further underscored the importance of protecting workers’ rights, particularly by guaranteeing paid sick and family leave. Paid sick and family leave helped ensure that workers who were sick with Covid-19—or those with sick family members—could stay home and minimize the spread of the virus. During the pandemic, workers in some industries were at heightened risk from the virus. Migrant workers, many of whom faced rights violations before the pandemic, were particularly vulnerable during this time and subject to numerous abuses.

During the pandemic, some governments bolstered worker protections. In Italy, the national government adopted a series of measures to protect some workers from being fired, provided cash infusions for freelance workers and poor families, and supported families with young children by ensuring the right to parental leave and providing childcare vouchers.

Many governments guarantee some paid sick leave to all workers, but many others—most notably the US among developed economies—do not. In the US, low-wage earners, service workers, informal workers, and gig economy workers are among those least likely to have paid sick leave, which has made them more vulnerable to contracting or spreading the virus. People of color—particularly women and immigrants—are over-represented in low-wage service jobs, and Covid-19 disproportionately affected Black, Latinx, and Native communities. Many, particularly in agriculture and food production, faced unsafe working conditions leading to outbreaks.

Workers in specific industries faced heightened risks of contracting Covid-19 or other abuses.

In Germany, large outbreaks of Covid-19 among meat plant workers highlighted the deplorable living and exploitative working conditions in the industry. Many employees were migrants and worked for subcontractors. In July, the government presented a bill to ban the use of subcontractors and increase companies’ accountability for health and safety of workers.

In Bangladesh, over one million garment workers were laid off following massive order cancellations, and denied owed wages. Retailers took advantage of the crisis by demanding discounts on producer prices, putting pressure on workers to return to work for lower wages, often without adequate PPE, reliable health care, or sick leave. The Bangladesh government provided US$600 million in subsidized loans to companies to support payment of wages to workers in the garment sector, though it remains unclear whether back wages have been paid.

In Democratic Republic of Congo, many copper and cobalt mining workers were ordered by managers to remain confined to their work site 24 hours a day, seven days a week, or face layoffs, as companies rolled out policies aimed at preventing the spread of Covid-19 while continuing operations. Ultimately, the government ordered multinational mining companies to stop confining workers.

Migrant workers often faced serious rights violations during the pandemic and were largely excluded from unemployment schemes.

In Kuwait, many migrant workers were dismissed without their wages, trapped in the country, and unable to leave due to travel restrictions and expensive flight tickets. They also faced increased risks of abuse by employers due to lockdown restrictions that left them confined to employers’ homes. In Oman, migrant domestic workers faced increased risks of similar abuse, and some were trapped from being able to leave the country due to travel restrictions. State companies were told to ask non-Omani employees to “leave permanently,” despite the fact that expatriates make up almost 40 percent of the total population. An August 2020 report on Qatar by Human Rights Watch found that longstanding wage-related problems migrants workers faced—including delayed wages, unpaid wages, and forceful terminations—were exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Other countries where preexisting abuses against migrant workers were exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic include Jordan, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE.

Right to Housing

The Covid-19 pandemic threatened the right to adequate housing. As people lost work and income, housing became more insecure and less affordable for millions in both high- and low-income countries. Several governments moved to protect the right to housing, including through the provision of basic utilities to homes, such as water and waste services.

Those who live from one payday to the next, with minimal savings, and who face high levels of unemployment, such as people with disabilities, face housing insecurity even in normal circumstances, which the economic hardships of the pandemic exacerbated. Failure to pay rent, mortgage, or utilities may result in evictions, foreclosures, and shutoffs of water or electricity services, compounding the crisis for families and communities around the world.

In EU countries, unemployment and underemployment amid lockdowns and the economic recession left many falling behind on rent and mortgage payments and threatened continued access to housing. Several EU member states—including France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Spain, and the UK—announced or extended temporary bans on evictions. In some countries, the bans were limited to private tenancy agreements. Other countries took wider action, offering rent relief, temporary mortgage debt relief, and protected mortgage-holders from eviction, too.

In the US, by May 2020, 43 out of the nation’s 50 states had active eviction moratoriums limiting landlords’ ability to remove tenants who could not pay their rent. By August, however, only about 20 states still had active moratoriums. In September, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the US national public health institute, passed a nationwide moratorium on evictions giving renters some protections, and, in January 2021, President Joe Biden extended it through March. However, due to flaws in the moratorium and its implementation, many renters have either lost or risk losing their homes due to their inability to pay.

In some countries, people were not protected from eviction during the pandemic. In Angola, authorities continued during the pandemic to forcibly evict people and conduct demolitions without necessary procedural guarantees or guarantees of alternative housing. In Bahrain, authorities forced workers out of their accommodations by cutting off electricity and water during the peak of the summer, without providing for alternative housing. In India, millions of migrant workers, fearing wage loss and evictions if they could not pay rent, walked back to their villages and towns after the government announced an abrupt lockdown with a four-hour notice. In South Africa, despite a federal ban on evictions, the country’s local governments evicted people from homes built on public land without providing alternative sites to shelter in place. In Kenya, in early May, authorities evicted more than 8,000 people in two of Nairobi’s informal settlements. Deprived of their homes, hundreds of families were forced to sleep out in the open for weeks. They not only had to gather around fires for warmth, but were also at a higher risk of exposure to Covid-19 and of being arrested by government authorities for breaking curfews and other restrictions.

The heightened risks of exposure to the coronavirus that stem from failure to realize the right to adequate housing is particularly acute for people experiencing homelessness and those living in substandard housing, including in refugee and IDP camps, slums, some types of worker and public housing, informal settlements of undocumented migrants, and severely overcrowded locations.

Some governments such as the United Kingdom, France, and some US states and cities provided shelter for thousands of people in vacant hotel rooms, Airbnb units, hostels, and other individual housing options that allow access to hygiene facilities and the space to effectively maintain social distancing. These positive measures also include, in some countries, an extension of the right to remain in reception centers for asylum seekers beyond established time limits. But most governments have identified these options as a short-term health measure. Longer-term approaches that work best with national contexts should be considered.

Recommendations

Governments should protect workers’, including migrant workers’, rights including:

- the right to a living wage;

- the right to association and collective bargaining;

- basic labor protections such as paid sick or family leave.

During lockdowns and in the wave of the economic crisis precipitated by the pandemic, governments should:

- Protect people who face homelessness as a result of eviction due to inability to pay rent or mortgage, at a minimum by ensuring they have access to alternative adequate housing;

- Halt utilities disconnections, in particular for water and sanitation services, for inability to pay and reconnect where services have already been cut.

As countries ease lockdown restrictions, economic recovery that ensures an adequate standard of living for everyone will depend on improved social protection and broad-based fiscal support. Governments should:

- Ensure recovery plans take into account ways in which some groups have suffered more than others during the pandemic and work to ensure that recovery efforts correct the inequalities that led to disparities in the first place;

- Avoid austerity measures that harm rights, which in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis entrenched inequalities;

- Plan for and commit sufficient public investment to ensure adequate health care, education, water and sanitation services, and housing, for all; Implement policies to guarantee the right to social security.

Covid-19 and Technology

During the pandemic, many governments launched and expanded digital surveillance initiatives in their efforts to contain the virus, sometimes with private sector support. These range from contact tracing apps that identify and inform people who may have come into contact with an infected person, to facial recognition cameras that enforce quarantine measures, to algorithmic risk assessments that monitor and restrict people’s movements based on their location and health histories. These initiatives collected and analyzed a wide range of personal and sensitive data, from GPS and Bluetooth to cell site location data. Virtually all of these technologies pose serious risks to privacy and human rights. Examples of these initiatives include:

In March 2020, Armenia required telecommunication companies to provide authorities with phone records for all customers in order to facilitate tracking of people exposed to the virus. For months, authorities refused to reveal information about who was in charge of the tracking system, saying that it was developed by volunteer programmers, free of charge; their names were eventually revealed without their affiliations. Authorities suspended the program in September.

In Ecuador, the government rolled out several initiatives that used mobile location and other personal data to identify people who may have come into contact with an infected person and to pinpoint large gatherings. This involved not only the collection but the aggregation, processing, and sharing of personal information.

The South Korean government in March 2020 adopted a data-intensive contact tracing program using mobile location, CCTV cameras, and debit and credit card data. It created a publicly available map of the movements of people infected with the virus and sent out cellphone notifications to large numbers of people with detailed information on confirmed Covid-19 cases, including age, gender, and places visited before being quarantined. This public information allowed people to identify infected persons, leading to public harassment and “doxing” (the publication of personal information on the internet). Later, public health bodies issued guidance not to publish patient age, sex, nationality, workplace, travel history, or home residency location, although some local governments continued to disclose such information despite this guidance.

In cities across China, an app called Health Code assigned individuals one of three colors (green, yellow, or red), depending on a range of factors such as whether people had been to virus-hit areas. To enter buildings, go to the supermarket, or use public transport, people had to scan a QR code at a manned checkpoint. Users have complained that the apps’ decisions are arbitrary and difficult to appeal, and have a wide-ranging impact on their lives and freedom of movement.

In Russia, many regions introduced a pass system that required people to obtain permission online or through SMS to leave the immediate vicinity of their homes. Moscow city authorities also introduced a highly intrusive app to track the whereabouts of people exposed to or infected with Covid-19 or displaying symptoms of respiratory disease. The app automatically issued fines that in many cases were wrongly applied. After protracted public outcry, several improvements were introduced. Moscow authorities have also tapped into the city’s network of facial recognition cameras to monitor the movements of people under quarantine orders.

The underlying logic of mobile tracking—that users are uniquely linked to their phones—is ill-suited for people who cannot afford mobile connections or devices, share a single connection or device, or frequently experience internet outages, such as many migrant workers and refugees. Women are more likely to fall on the wrong side of the digital divide, and apps may not be developed to be accessible for older people and people with disabilities. People without smartphone or internet access have also been denied entry to public and private spaces because they cannot provide the digital proof required to show that they are safe for entry.