Summary

Civilians in Yemen are facing one hardship after another. A decade of economic and political crisis and more than five years of war have ravaged the country. Thousands of civilians have been killed or injured, and at least 3.6 million people have been forced to flee their homes due to a conflict that involves at least six regional and international powers.

With about 24 million of Yemen’s 30 million people in need of some form of assistance, the United Nations calls Yemen the world’s worst humanitarian crisis. Cholera and other disease outbreaks are common, malnutrition is widespread, water is scarce, and the healthcare system is crumbling, with only half of the country’s 5,000 or so health facilities fully operational and with massive medical supply and staff shortages. In August 2020, the UN warned the country was again on the brink of full-scale famine.

Now Yemenis, many already in a weakened state of health, face the deadly Covid-19 pandemic. As of August 30, the Yemeni government had confirmed only 1,950 cases and 564 Covid-19-related deaths, but the UN has warned that the actual number of cases and deaths is much higher, and that the novel coronavirus that causes Covid-19 is “likely to spread faster, more widely and with deadlier consequences than almost anywhere else.”

The response to Covid-19 in Yemen has been hampered by limited testing, a lack of healthcare centers, and severe shortages of medical supplies and personal protective equipment (PPE). Scores of healthcare workers, underpaid or not paid at all and with little or no access to PPE, have left their posts, forcing even more health centers to close. In the country’s north, the political movement and armed group known as the Houthis have stigmatized being infected by the virus and threatened medical workers, leaving sick people afraid to seek treatment and cemetery workers burying the dead in secret. As of late July, the Houthis had recorded only a few cases of Covid-19 and stopped all social distancing measures after saying the virus no longer posed a threat.

Efforts to prevent the spread of Covid-19 and respond to other urgent health needs in Yemen have been severely hampered by onerous restrictions and obstacles that the Houthi and other authorities have imposed on international aid agencies and humanitarian organizations. Since May, the Houthis have blocked 262 containers in Hodeida port belonging to the World Health Organization as well as a large shipment of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) for the Covid-19 response. The Houthis have tried to use some of the shipments as bargaining chips in negotiations relating to the lifting of other aid obstacles and agreed to release 118 of the containers in late August or early September. The restrictions have been compounded by a collapse in donor funding and a new fuel crisis, triggered by disagreements over how to regulate taxation of imported fuel, which hospitals and water pumps depend on.

This report, based on interviews with 35 humanitarian workers, 10 donor officials, and 10 Yemeni health workers, uncovers the complex web of restrictions on aid and the devastating impact they are having on Yemenis’ access to health care, water, food, sanitation, and other basic needs.

Between 2015 and 2019, international donors gave the UN-led aid response in Yemen US$8.35 billion, including $3.6 billion in 2019 that reached almost 14 million people each month with some form of aid, up from 7.5 million people in 2018. However, aid agencies say that in 2019 and 2020 they spent vast amounts of their time and energy struggling to get approvals country-wide to provide assistance in accordance with humanitarian principles and without the authorities’ interference.

Partly in response to the obstruction of aid, donor support to UN aid agencies collapsed in June 2020, particularly from Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and the United States, which channeled over half of its aid to southern Yemen. As of August 28, aid agencies had received only 24 percent of the $3.4 billion they had requested for the year.

The funding crisis has had a dire impact on Yemeni civilians, including the halving of food assistance to 9 million people and the suspension of support to healthcare services, which the UN says has “put the lives of millions on the line.”

Despite donors’ understandable frustration with aid obstruction, and concerns about how much aid has been co-opted or diverted by the Houthi authorities to fund their war effort, this report calls on donors to continue to fund projects carried out by UN agencies and humanitarian organizations in Yemen that provide much-needed assistance, while also working to ensure that humanitarian principles of independence and impartiality

are upheld.

Current examples of interference and obstruction by the Houthi and other authorities include lengthy delays for approval of aid projects, blocking aid assessments to identify peoples’ needs, attempts to control aid monitoring and recipient lists to divert aid to those loyal to the authorities, and violence against aid staff and their property.

The Houthis have a particularly egregious record of obstructing aid agencies from reaching civilians in need, at least in part to divert aid to Houthi officials, their supporters, and Houthi fighters. In 2019 and 2020, aid workers had to push back against Houthi officials insisting that aid groups hand over assets, such as cars, laptop computers, and cellphones to the Houthis at the end of projects. Yet obstruction in government-held areas in the south and east are also on the rise. In July, the UN humanitarian chief, Mark Lowcock, told the UN Security Council that aid agencies were facing an “uptick in violent incidents targeting humanitarian assets and local authorities adding new bureaucratic requirements.”

On July 14, a senior member of the Houthi Supreme Political Council in Sanaa, Mohammed al-Houthi, responded to Human Rights Watch’s letter of July 7 outlining this report’s findings. He said that the Houthis had no interest in obstructing aid, that their procedures try to ensure aid projects meet principles of “transparency and integrity,” that aid agencies alleging aid obstruction are following “political orders” from the United States authorities, and that some aid projects do not address Yemen’s most urgent humanitarian needs and have inflated budgets.

On August 13, the Houthis’ Supreme Council for Management and Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs and International Cooperation (SCMCHA) also replied in similar terms to the July 6 letter, stating that allegations of obstruction of aid “lack credibility” and are “baseless”.

As of September 9, Human Rights Watch had not received any feedback to its July 6 letters to the internationally recognized Yemeni government and to officials in the Southern Transitional Council (STC).

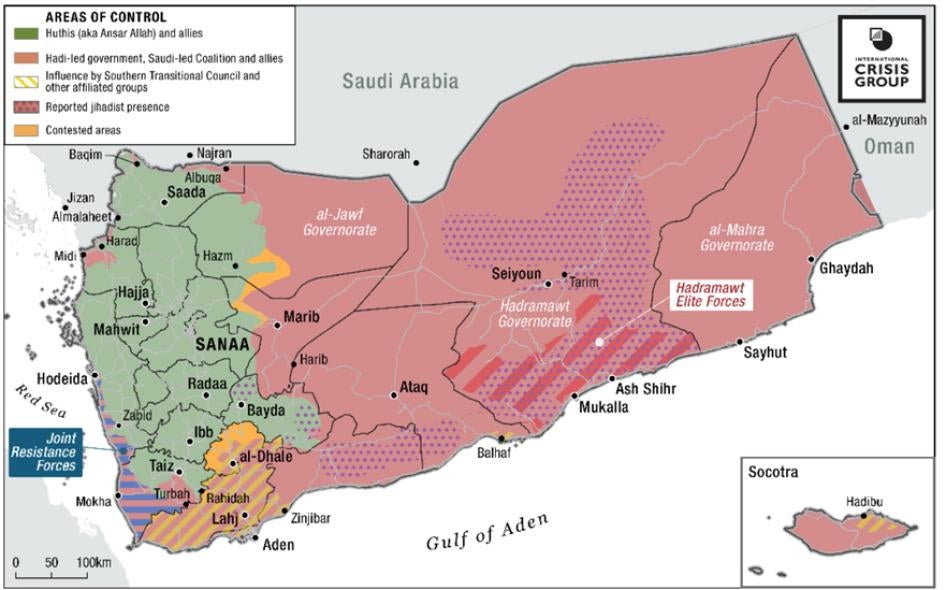

After the Houthis took control of the country’s capital, Sanaa, and other parts of northern Yemen in 2014 and early 2015, a coalition led by Saudi Arabia began airstrikes against areas held by the Houthis in March 2015. The original coalition members included: Bahrain, Egypt, Jordan, Kuwait, Morocco, Qatar, Sudan, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). The operations were ostensibly in response to a request from then-Yemeni President Abdu Rabu Mansour Hadi. Coalition members, notably Saudi Arabia and the UAE, have purchased weapons from the United States, the United Kingdom, and France, among others.

The Houthis, a non-state armed group that have received some support from Iran, have controlled much of northern and central Yemen since 2014, including the country’s capital, Sanaa, where the Houthi authorities are now based. After the Houthis’ takeover of Sanaa in September 2014, the Yemeni government established a temporary capital in March 2015 in the southwestern port city of Aden and retained control over much of the sparsely populated central and eastern parts of the country.

In January 2018, forces loyal to the UAE-backed Southern Transitional Council (STC) clashed with the Yemeni government and took control over most of Aden and other parts of the south in August 2019. A year later, the STC began to withdraw from positions in Aden it had seized from the Yemeni government, but as of late August fighting and tension continued between the two sides.

The Saudi-led coalition has conducted numerous indiscriminate and disproportionate airstrikes, killing and wounding thousands of civilians and hitting civilian structures in violation of the laws of war. Both Yemeni government and Houthi forces have recruited children. Houthi forces have used banned antipersonnel landmines, fired artillery indiscriminately into cities, killing and wounding civilians, and launched indiscriminate ballistic missiles into Saudi Arabia. Some unlawful coalition and Houthi attacks are apparent war crimes. Yemeni forces, the Houthis, and the Saudi-led coalition have attacked over 100 medical facilities. The US, UK, France, Canada, and other countries have sold arms to the Saudi-led coalition, while also funding the humanitarian aid effort. Due to these arms sales, they have contributed to Yemen’s humanitarian crisis and may be complicit in laws-of-war violations.

The Saudi-led coalition imposed a naval and air blockade on Yemen in March 2015 that severely restricted the flow of food, fuel, and medicine that the vast majority of the civilian population depended on, in violation of the laws of war. This included an unofficial ban on importers using standard 6 to 12 meter-long metal containers to ship goods, which the UN says was lifted for the first time on August 12, 2020 for one vessel, and which has forced importers to use more expensive transportation and off-loading methods, resulting in a significant increase in the price of essential commodities in Yemen. Since 2018, the coalition has also continued to unnecessarily delay imports of some essential goods and humanitarian aid into northern Yemen.

Since late 2019, the UN, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and increasingly aid donor countries have pressed the Houthis to take concrete steps to facilitate humanitarian agencies’ work. In mid-2020, this resulted in the Houthis signing backlogged project agreements submitted in 2019. However, aid workers expressed concern that the real test was whether these agreements will translate into action by civilian and security officials at checkpoints and in villages, towns, and cities or whether the Houthis will revert to their longstanding “one step forward, three steps back” practice of making concessions, only to then restrict aid groups’ access in new ways.

Making matters worse, aid workers say the humanitarian community’s response to aid obstacles in Yemen, particularly in the Houthi-controlled parts of the country, has had numerous shortcomings and may have exacerbated the problem. These include: focusing advocacy on the wrong officials; involvement of senior UN officials in what should have been solely humanitarian negotiations; conceding to a series of demands relating to the control of aid projects that encouraged the authorities to seek ever-greater control; failing to adopt a unified aid agency approach to pushing back on obstacles and instead letting individual agencies fight their own battles; a lack of strategic analysis of what exactly causes specific types of aid obstruction; channeling vast amounts of money to clearly corrupt ministries without sufficient conditions attached; and failing to transparently investigate and report on allegations of UN agencies’ complicity in aid diversion, including proactively reporting on the diversion of UN salary and incentive payments to Yemeni officials.

International humanitarian law requires parties to the conflict not to withhold consent for relief operations on arbitrary grounds and to allow and facilitate rapid and unimpeded impartial aid to civilians in need. They may take steps to control the content and delivery of humanitarian aid, such as to ensure that consignments do not include weapons. However, deliberately impeding relief supplies is prohibited. Lawful military restrictions on aid cannot have a disproportionate effect on the civilian population.

The Houthi authorities’ onerous bureaucratic aid requirements without justification have blocked millions of Yemenis from life-saving aid. Although not the recognized government of Yemen, the Houthis should nonetheless act to protect the human rights of all people in territory they control, including the rights to life, to health, and to an adequate standard of living, including food and water. International human rights law obligates government-backed authorities in the south to protect basic rights. Although limited resources and capacity may mean that economic and social rights can only be fully realized over time, the authorities are still obliged to ensure minimum essential levels of health care are met, including essential primary health care.

The Yemeni government has also imposed onerous bureaucratic requirements on aid agencies that the agencies say have unnecessarily delayed aid from reaching millions of civilians, in violation of the government’s human rights obligations.

Since June 2020, a dispute between the Houthis and the Yemeni government about the use of tax revenues from fuel arriving at Hodeida port has blocked numerous commercial vessels carrying fuel off the coast, which the UN has warned threatens Yemenis’ access to food, hospital operations, and water supplies. In late August, the UN said the ensuing fuel shortages had caused a reduction and suspension of aid projects covering healthcare, water and sanitation, food, and shelter affecting hundreds of thousands of people.

To begin to reverse the appalling humanitarian situation in Yemen, the Houthis and the Yemeni government should immediately lift all unnecessary obstacles to facilitating the whole population’s access to life-saving health care, water, food, and other services. The Houthis and the authorities in the south should introduce a transparent and accessible public information campaign about the nature and extent of Covid-19, and the necessary steps individuals and the authorities, working closely with aid agencies, need to take to prevent transmission of the virus and care for those infected.

Senior UN officials, including the humanitarian coordinator in Yemen and UN emergency relief coordinator, Mark Lowcock, should continue to regularly report to the UN Security Council, and ensure that those reports fully detail the nature of obstacles to aid imposed by the authorities in Yemen’s north and south and on any progress to remove those obstacles. The Council should identify senior Houthi and Yemeni government officials responsible for obstructing the delivery of humanitarian assistance and impose targeted asset freeze and travel ban sanctions on them under UN Security Council Resolution

2140 (2014).

International donors should increase at the highest possible political level pressure on Houthi authorities and the Yemeni government to lift aid obstacles, including any affecting the Covid-19 response. Donors should generously fund UN agencies and humanitarian organizations in Yemen that provide assistance, while upholding humanitarian principles of independence and impartiality.

In light of the wide-ranging concerns about the humanitarian community’s response to aid obstruction in Yemen, the Human Rights Council should mandate the UN-established Group of Eminent Experts (GEE) on Yemen to conduct an independent and comprehensive review of the extent of the obstruction of aid in north and south Yemen since 2015 and the humanitarian community's response to the obstruction. The UN Security Council’s Yemen Sanctions Committee should also mandate the Panel of Experts on Yemen to conduct such a review. The UN’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) should work closely with the GEE and the Panel of Experts on Yemen, and the resulting reports to the Human Rights Council and the Security Council should make concrete recommendations for what steps OCHA, other UN agencies and officials, and other humanitarian organizations should take to more effectively respond to Yemen’s aid crisis.

Methodology

Between May 6 and August 31, 2020, Human Rights Watch interviewed 35 humanitarian workers about obstacles to humanitarian aid they and their agencies face in Yemen, 10 donor government officials about their engagement with the Yemeni authorities and aid agencies in Yemen, 10 Yemeni healthcare workers about their ability to respond to Covid-19 and other healthcare needs, and 6 Yemen experts.

Given the restrictions on travel due to the Covid-19 pandemic, Human Rights Watch was unable to travel to Yemen for this research. All interviews were conducted by phone in Arabic or English. We interviewed a number of people more than once. We explained the purpose of the interviews and how the information provided would be used and gave assurances of anonymity. No interview subject was promised or provided a service or personal benefit in return for their interviews.

On July 7, Human Rights Watch wrote to the Houthi authorities, the internationally recognized Yemeni government, and to the Southern Transitional Council outlining our findings and requesting comment. On July 14 and August 13, the Houthi authorities responded, and their response is reflected in this report. As of September 9, we had received no reply from the Yemeni government or the Southern Transitional Council.

Recommendations

To the Houthi Authorities

- Immediately facilitate unimpeded access for United Nations humanitarian aid agencies and other humanitarian organizations and their staff to all areas so that they can identify humanitarian needs and impartially assist all people in need;

- End all unnecessary obstacles and interference identified in this report and work closely with UN agencies and non-UN aid organizations to expeditiously process all future aid project proposals and travel requests;

- Introduce a transparent and accessible public information campaign about the nature and extent of Covid-19, and the necessary steps individuals and the authorities need to take to prevent transmission of the virus and care for those infected, with priority given to those deemed most at risk of serious illness, including people with chronic health conditions and older people;

- Work closely with the World Health Organization (WHO) and other humanitarian and development agencies to limit the spread of Covid-19 and treat those infected;

- Facilitate meetings in Yemen with donor government officials at senior levels to help secure the maximum donor support to address the humanitarian crisis;

- Avoid government regulations on medicine, fuel, and other goods that disrupt humanitarian assistance without justification.

To the Government of Yemen

- End all unnecessary obstacles and interference identified in this report and work closely with UN agencies and non-UN aid organizations to expeditiously process all future aid project proposals and travel requests;

- Facilitate meetings in Yemen with donor government officials at senior levels to help secure the maximum donor support to address the humanitarian crisis;

- Introduce a transparent and accessible public information campaign about the nature and extent of Covid-19, and the necessary steps individuals and the authorities need to take to prevent transmission of the virus and care for those infected, with priority given to those deemed most at risk of serious illness including people with chronic health conditions and older people;

- Avoid government regulations on medicine, fuel, and other goods that disrupt humanitarian assistance without justification.

To the Southern Transitional Council

- Introduce a transparent and accessible public information campaign about the nature and extent of Covid-19, and the necessary steps individuals and the authorities need to take to prevent transmission of the virus and care for those infected;

- Do not arbitrarily impede humanitarian assistance or aid workers at checkpoints.

To the UN Security Council

- Press all parties to the conflict in Yemen to lift the wide range of obstacles that hinder or prevent aid agencies from rapidly reaching people in need of humanitarian aid;

- Identify senior Houthi and Yemeni government officials responsible for obstructing the delivery of humanitarian assistance and impose targeted asset freeze and travel ban sanctions on them under UN Security Council Resolution 2140 (2014);

- The Council’s Yemen Sanctions Committee should mandate the Panel of Experts on Yemen to conduct an independent review of the extent of the obstruction of aid in north and south Yemen since 2015 and the humanitarian community's response to the obstruction; the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) should work closely with the Panel of Experts on Yemen, and the resulting report, to be presented to the Security Council, should make concrete recommendations for the steps OCHA, other UN agencies and officials and the broader humanitarian community should take to more effectively respond to aid obstacles.

To the UN Secretary-General, the UN Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator, the Humanitarian Coordinator in Yemen and the UN Panel of Experts on Yemen

- Regularly report to the UN Security Council in detail on the nature of obstacles to humanitarian aid imposed by the authorities in the north and south of Yemen and on any progress made in lifting them.

To the UN Human Rights Council

- Mandate the UN-established Group of Eminent Experts (GEE) on Yemen to conduct an independent review of the extent of the obstruction of aid in north and south Yemen since 2015 and the humanitarian community's response to the obstruction; the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) should work closely with the GEE and the resulting report, to be presented to the Human Rights Council for its consideration at its 47th session in September 2021, should make concrete recommendations for the steps OCHA, other UN agencies and officials and the broader humanitarian community should take to more effectively respond to aid obstacles.

To Donor Governments Providing Support to Yemen and the UN-led Response

- Continue to engage with the authorities in the north and south to lift obstacles to aid, including any affecting the Covid-19 response, and ensure that future engagement is led on all sides at the highest political level possible;

- Urgently increase support to UN agencies and other humanitarian organizations in Yemen that can reach and provide impartial assistance to people in need, focusing on health care, food security, water and sanitation, and livelihoods, among other humanitarian assistance;

- Urge the Human Rights Council to mandate the GEE on Yemen, and urge the UN Security Council’s Yemen Sanctions Committee to mandate the Panel of Experts on Yemen to conduct an independent review of the extent of the obstruction of aid in north and south Yemen since 2015 and the humanitarian community's response to the obstruction and provide concrete recommendations on the steps that should be taken to more effectively respond to aid obstacles.

I. Conflict and Humanitarian Crisis in Yemen

Starting in mid-2014, a northern-based political movement and armed group, which calls itself Ansar Allah and is commonly known as the Houthis, in alliance with former Yemeni President, Ali Abdullah Saleh, expanded its control to central western Yemen, including the capital, Sanaa, and the Red Sea port of Hodeida, where the vast majority of the population lives.[1] In March 2015, a coalition of states led by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) began military operations against the Houthis that have continued until the present. The Saudi-led coalition has supported the internationally recognized Yemeni government, based in the southern port city of Aden, and purchased arms from the United States, the United Kingdom, France, and Canada, among other countries. The Houthis have received some support from Iran.[2]

One study concluded in October 2019 that armed attacks during the war in Yemen have killed over 12,000 civilians.[3] The Saudi-led coalition has conducted numerous indiscriminate and disproportionate airstrikes, killing and wounding thousands of civilians and hitting civilian structures in violation of the laws of war.[4] Yemeni government and Houthi forces have recruited at least 1,100 children.[5] Houthi forces have used banned antipersonnel landmines, fired artillery indiscriminately into cities such as Taizz, killing and wounding civilians, and launched indiscriminate ballistic missiles into Saudi Arabia, including towards Riyadh’s international airport. Some of these attacks were apparent war crimes.[6] The Houthis, the Saudi-led coalition, and Yemeni government forces have attacked at least 120 medical facilities.[7] The US, UK, France, Canada, and other countries have continued arms sales to the coalition, which has contributed to the humanitarian crisis in Yemen and may make them complicit in laws-of-war violations.[8]

After the start of hostilities in March 2015, the Saudi-led coalition imposed a naval and air blockade on Yemen that severely restricted the flow of food, fuel, and medicine on which the vast majority of the population depends, in violation of the laws of war.[9] This included an unofficial ban on importers of goods using standard 6 to 12 meter-long metal containers which resumed for the first time on August 12, 2020, and which has forced importers to use more expensive transportation and off-loading methods resulting in a significant increase in the price of essential commodities in Yemen.[10]

Despite the coalition’s announcement in April 2018 that all air, land, and sea ports were open, the coalition continued to restrict and unnecessarily delay some essential goods and humanitarian aid cleared by the United Nations for docking in Hodeida port.[11] Throughout 2019, politically driven bureaucratic procedures also meant importers of goods and fuel faced “corrupt practices” and “a lack of predictability in the [extent of] delays” in the coalition’s decision on whether to allow UN-cleared vessels to dock.[12] In May 2020, aid workers told Human Rights Watch that importers continued to face a series of onerous bureaucratic requirements that slowed the delivery of humanitarian assistance.[13]

In January 2018, forces loyal to the UAE-backed Southern Transitional Council (STC) clashed with the Yemeni government and in August 2019 took over most of the southern city of Aden.[14] In April 2020, the STC declared self-governance in Aden and other parts of the south where it continued to fight Yemeni government forces until late July.[15] An attempt to reunify the STC and the Yemeni government through a power-sharing arrangement known as the Riyadh Agreement, signed in Saudi Arabia in November 2019, has not yet succeeded, but in late July the STC agreed to give up on self-rule and become part of a new Yemeni government by the end of August.[16] However, on August 25, the STC announced it was suspending talks with the Yemeni government and fighting resumed between the two sides.[17]

In early April 2020, Saudi Arabia unilaterally declared a ceasefire, although its airstrikes continued.[18] Since then, the Houthis and Saudi Arabia have each accused the other of attacking their forces.[19]

The United Nations has called Yemen the world’s worst humanitarian crisis, with about 80 percent of the country’s 30 million people needing some form of aid.[20] A decade of political and economic crisis and more than five years of armed conflict have further undermined health care and other social services in Yemen, already the poorest country in the Middle East.[21] During the conflict, over 2 million Yemenis have contracted cholera and there have been outbreaks of other diseases.[22] The conflict has heavily affected at least 4.5 million people with disabilities, many of whom have acquired new secondary conditions since the beginning of the conflict.[23] There is widespread malnutrition, which affects 2 million children under the age of 5.[24] At least 1 million pregnant women, out of a population of 6 million women of reproductive age, are malnourished.[25] Hunger and preventable diseases have killed tens of thousands of people, including at least 85,000 children under 5 who are estimated to have died from severe acute malnutrition.[26] In July, the UN warned that the country was in danger of returning to “the brink of a full-scale famine.”[27]

In June, the World Health Organization (WHO) called for a massive scale-up in all health operations, including for Covid-19, to help protect a population with weakened immune systems, including older people and children, and at least 3.6 million internally displaced people.[28] The UN also warned in June that without foreign aid the country’s water, sanitation, and hygiene systems and institutions would collapse, triggering a “public health disaster.”[29]

II. Obstruction of Aid in Houthi-Controlled Areas

The Houthis have a long history of obstructing aid agencies from reaching civilians in need, in part to divert aid to Houthi officials, their supporters, and Houthi fighters. In 2008, Human Rights Watch documented that Houthi forces, who at the time were battling government forces under then-President Ali Abdullah Saleh, prevented aid agencies from reaching civilians in need in areas under their control.[30] In 2015, there were reports of the Houthis blocking aid access to the embattled city of Taizz.[31] Since at least 2016, the Houthis have obstructed aid agencies from reaching millions of civilians.[32] This includes agencies trying to respond to the country’s cholera crisis in 2017.[33] According to the United Nations, Houthi obstruction of aid significantly increased in 2019 and 2020.[34]

Aid workers interviewed for this report referred to years of lengthy negotiations with the Houthi authorities to get permission to provide life-saving assistance in Houthi-held areas. They said that while the Houthis want assistance to flow, they want to control it in a way that compromises humanitarian principles of humanity (addressing suffering wherever it is found), neutrality (not favoring any side in a conflict), impartiality (providing aid solely on basis of need and without discrimination), and independence (separating humanitarian objectives from political, economic, military, or other objectives).[35]

In November 2019, the Houthis, who control government ministries in the capital, Sanaa, created the Supreme Council for Management and Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs and International Cooperation (SCMCHA), to approve and regulate aid and development projects and travel permits for humanitarian aid project staff.[36] SCMCHA replaced the National Authority for the Management and Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs and Disaster Recovery (NAMCHA).[37]

Aid workers with UN agencies and independent organizations described to Human Rights Watch in detail the range of Houthi-imposed obstacles that blocked, severely delayed, or restricted their work since early 2019, affecting vast numbers of people in need. One aid agency report stated in February 2020 that “some NGOs are … facing [a] de-facto halt in operations due to inflexibility by [Houthi] authorities.”[38] In June, the UN said aid interference increased tenfold between 2018 and 2019 and got even worse in 2020, making it “increasingly difficult to … reach people who need it most,” including at least 11 million “vulnerable people” in 200 of the country’s 333 districts officially classified as “hard-to-reach.”[39]

Yet some agencies say there have been some improvements in recent months. As part of their call on the United States to lift its March 2020 suspension of some aid to northern Yemen, six international aid groups said in August that there was “now an improved environment for the delivery of life-saving assistance in northern Yemen.”[40] On July 14, a senior member of the Houthis’ Supreme Political Council in Sanaa, Mohammad Ali al-Houthi, responded to Human Rights Watch’s letter of July 7 outlining this report’s findings. He said that the Houthis recognized the importance of working with the UN and aid organizations who play an important role in addressing the country’s humanitarian crisis, that the Houthis had no interest in impeding humanitarian access and that UN and aid organization officials had praised the Houthis for removing aid obstacles. He also stressed that the Houthis’ procedural requirements for aid projects aim to ensure they meet principles of “transparency and integrity,” that the Houthis were willing to respond live in the media to anyone alleging the Houthis obstruct aid and that the Houthis were willing to host or participate in an international conference on the humanitarian situation in Yemen.

He continued that aid agencies’ “discourse about … obstacles to their work … is the result of responding to political orders by the American Administration, as it oversees the aid at the United Nations [in Yemen]” including to help “justify the American decision to reduce aid to Yemen,” and that “some organizations are affiliated to countries that have other agendas.” He also said the Houthis are concerned that some aid agency projects have questionable aims and do not address the most urgent humanitarian needs, and that some project budgets exceed the actual cost incurred.[41]

On August 13, SCMCHA also responded to Human Rights Watch’s July 7 letter, making similar points to those expressed by Mohammad Ali al-Houthi, including that that allegations of aid obstruction “lack credibility” and are “baseless”.[42]

Regulations Excessively Restricting Aid Agencies

From January 2019 through August 31, 2020, the Houthis issued 385 directives and instructions regulating aid groups, of which 274 were being enforced in early September and over 20 of which were related to Covid-19.[43] Many of the directives either demanded the sharing of protected information or imposed restrictions on movement of staff and supply, on coordination meetings, on needs assessments, and on tendering and procurement processes.[44] According to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), these restrictions “violate humanitarian principles, agency rules and regulations, and contractual agreements with donors.”[45] The UN also said that where aid groups have not complied with directives, this “has resulted in arrests, intimidation, movement denials, suspension of deliveries of aid and services and occupation of humanitarian premises.”[46] Aid agencies writing to the Houthis said the regulations were “hindering and unnecessarily delaying humanitarian assistance to vulnerable people.”[47]

Delays and Refusals When Negotiating Agreements with Aid Groups

Authorities and aid groups worldwide sign agreements with governments, often known as Memorandums of Understanding (MOUs) that regulate their work. In Yemen these are termed a “Principal Agreement” (PA), which gives aid groups a legal basis to work there, and sub-agreements (SA), for every project as defined by the donor funding it.[48]

Official aid agency letters sent to the Houthis in late 2019 detailed how aid groups spent months asking the Houthis to delete clauses from a draft standard PA that would have prevented groups from receiving UN funding, hiring staff, and managing assets without interference by the Houthis, and from independently assessing needs and monitoring projects. All of these Houthi demands, the officials said, “would violate humanitarian principles,” which would prevent the aid groups from agreeing to them.[49]

After a February meeting with humanitarian officials in Brussels, in March 2020, donors set up a Technical Monitoring Group (TMG) to monitor aid access improvements in northern Yemen.[50] The group identified seven “pre-conditions” and 16 related “benchmarks” for the Houthis to comply with, including progress on signing PAs and SAs. In July, the TMG also requested and received information from aid agencies about southern authorities’ aid obstruction.[51]

According to a May TMG update, the Houthis had agreed to drop the problematic clauses and, as of March, had signed 21 PAs with aid groups.[52] However, as of late August, the UN had not obtained the Houthis’ agreement on a standard operating procedure for signing future PAs to avoid further lengthy delays.[53]

Aid groups have also long struggled to obtain Houthi approval for project SAs. An October 2019 UN letter to the Houthis said that SA approval delays were blocking aid groups from helping 4 million Yemenis “who desperately need assistance to cope with cholera, displacement, nutritional needs, famine prevention, protection problems, and health and livelihood challenges.”[54] In one case, an aid worker said that a refusal meant the aid group had been unable to carry out projects for thousands of particularly vulnerable children

and women.[55]

Several aid workers said that they had spent between five and 24 months – with the UN reporting an average of six months – negotiating SAs for their aid projects in 2018 and 2019.[56] According to the UN, only 60 percent of those projects were approved by the end of 2019.[57] Some of the approved SAs were later revoked due to subsequent disagreements between different ministries.[58] Sticking points that have delayed or blocked approval include the Houthis insisting that aid groups hand over assets, such as cars, laptop computers, and cellphones to the Houthis at the end of projects.[59]

The UN reported that as of late May, the Houthis and authorities in the south were refusing to sign off on 134 aid group projects worth US$303 million, affecting 9 million people in need, of which 96 worth $216 million affecting 7.7 million people were in the north.[60] By the end of August, the total had been reduced to 96 projects worth about $240 million affecting almost 6.7 million people, of which 67 were waiting for approval by the Houthis and 29 by the Yemeni government.[61] The majority of the projects approved by the Houthis in 2020 related to a 2019 backlog, in line with the donor monitoring groups’ priorities.[62]

An aid worker and a donor both said that just before and after the Yemen pledging conference in June, Houthi authorities had suddenly agreed to sign SAs from 2019, reflecting the Houthis’ apparent fear that donors would cut funds unless projects could go ahead.[63] In June alone, the Houthis signed more SAs than in any other month since January 2019.[64] A donor aid monitoring group as well as aid workers said that a number of the signed agreements still included “challenging” clauses, including with respect to who controlled aid agencies’ physical assets and procedures for controlling funds to respond

to Covid-19.[65]

Several aid workers stressed that in some cases, Houthi officials working for SCMCHA at the central level in Sanaa made “empty promises” when signing SAs because SCMCHA representatives and local-level Houthi officials could still block aid groups from carrying out projects by insisting on additional conditions that aid groups could not comply with without violating humanitarian principles.[66] One aid worker said local officials regularly blocked many of his aid agency’s projects at the local level, including by refusing to respect staff travel permits, by insisting on reporting requirements that were impossible to comply with and by purposefully misinterpreting SA clauses in ways that would compel his agency to violate humanitarian principles.[67]

As of late July, the UN was in the early stages of trying to obtain the Houthis’ approval for a new standard operating procedure to help rapidly process all future SAs.[68] Aid agencies stressed this was key to ensuring the Houthis would not revert to blocking countless more SAs by engaging in protracted negotiations with individual aid agencies over the content of every newly proposed SA.[69] As of late August, no such procedure had been signed.[70]

In July, aid agencies reported that in some cases the Houthis had allowed them to conduct Covid-19-related projects without SAs in place.[71]

Blocking Assessments and Interfering with Lists of Recipients of Aid

A fundamental aid agency activity is known as a “needs assessment” – identifying the number of people needing a certain type of assistance. These studies form the basis of their funding proposals to donors who want to know that their aid money will reach those who need it most. Aid agencies in northern Yemen have faced significant obstacles to doing needs assessments since at least 2017.[72]

Three agencies said that doing assessments in northern Yemen was “almost impossible,” as the Houthis want to control as far as possible which populations receive aid.[73] In June, the UN said that “assessments, monitoring and evaluation, training and outreach activities have been largely suspended” in Houthi-controlled territory.[74] However, in August, six international aid groups said that since then the Houthis had allowed some independent needs assessments and monitoring activities to take place.[75]

A UN official said that in early 2020 Houthi officials approved one type of survey needed to establish the level and severity of malnutrition and that aid agencies had carried it out soon after, before the first Covid-19 cases were detected in Yemen.[76] Between mid-May and the end of July, the Houthis refused to let the UN World Food Programme (WFP), other UN agencies and other members of the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification initiative access the survey data, without giving a convincing reason why they should not see

the data.[77]

A donor official said that another two surveys, including one on malnutrition – which the same donor official said had also taken a year to negotiate – had been approved but suspended “due to Covid-19 …despite [a UN proposal to put] social distancing protocols in place” to help carry out the survey safely.[78]

Without recent assessments, the UN’s June 2020 aid appeal for the whole of Yemen was based on assessments done in 2018, which were outdated given the deteriorating conditions and the additional negative effects of the Covid-19 pandemic on the population.

In January 2020, the UN Panel of Experts on Yemen reported that it was “particular[ly] concern[ed]” about “the manipulation of beneficiary lists and pressure to share these lists.”[79]

Almost all aid groups interviewed said the Houthis regularly tried to control the “beneficiary lists,” the names appearing on aid recipient lists. One agency said that “sometimes the list comes first from the authorities and then it is very hard to independently verify the identity of those on the list and negotiate changes.”[80] Another aid worker with close knowledge of the aid operation in Yemen in 2019 said that “the list always comes first from authorities, and aid agencies are then supposed to verify it but that rarely happens” and that when agencies try to amend a beneficiary list, the Houthis stop agencies from distributing the aid.[81]

A donor said that a major UN agency was still using beneficiary lists given to them by authorities in locations where the agency’s partner organization has had highly limited access and has been unable to verify beneficiaries’ identities.[82] Another aid agency in charge of a large number of projects said that authorities at the local level put huge pressure on their agency’s more vulnerable national staff, whose relatives are potential targets of retaliation, to hand over confidential aid recipient lists and to delete names or add new ones.[83]

Controlling Aid Monitoring and Aid Group Management of Material Assets

Several aid workers told Human Rights Watch that the Houthis regularly insist that UN agencies and other aid groups subcontract project work, including monitoring of aid, to organizations or businesses linked to the authorities, instead of awarding them through a fair bidding process.[84] Such practices have previously been reported.[85]

An aid worker with close knowledge of the Yemen aid operation in 2019 said that ministries that receive UN funds refuse to share beneficiary lists or dates and locations of aid distributions, so that the UN or other aid agencies cannot monitor who receives the aid. The aid worker said that this has led to at least one UN agency not knowing some of the locations where its aid is distributed.[86] A donor official said that if the Houthis do approve independent “third party monitors,” they often attempt to restrict or interfere in their work.[87] According to another aid worker, in one case in 2019, Houthi officials threatened to kill an independent monitor and arrested another.[88] Another aid worker said that in June and early July 2020, the Houthis were blocking third party monitors from carrying out their work, resulting in protracted and “brutal” negotiations.[89]

Aid workers said that the Houthis introduced a new directive on June 3 that prohibits foreign entities who do not have a registered office in Yemen to carry out independent monitoring of aid projects, which would significantly decrease the number of companies not tied to the Houthis who can do such work.[90]

In January 2020, the UN Panel of Experts on Yemen reported that it had received information about “illegal seizures of the personal property of humanitarian workers and property belonging to humanitarian organizations in Sanaa.”[91]

Two letters from aid officials to Houthi authorities, seen by Human Rights Watch, as well as accounts from aid workers, noted that the Houthis have repeatedly sought to pressure aid groups into handing over control of their physical assets including warehouses, vehicles, laptop computers, and cellphones.[92] Two aid workers said that the Houthis had agreed to drop this demand from some project agreements that were finally signed in May

and June.[93]

Blocking Staff from Entering the Country

Aid workers interviewed by Human Rights Watch described in detail their frustrations at the Houthis refusing to allow staff with visas from entering the country in February and early March 2020, before the first cases of Covid-19 were detected in Yemen, or for refusing visas for arbitrary or no reasons.[94] One said that the Houthis have long used the process of granting international staff visas as a bargaining chip with aid agencies and that in some months the process was easier than in others. This aid worker said this affected their agency’s ability to oversee and manage projects, including in ways that reduced the risks to which Yemeni staff were exposed.[95]

According to another aid worker, in early March the Houthis told agencies that the Covid-19 pandemic meant they would have to stop all aid group staff from flying to the capital, Sanaa, or from reaching Sanaa by road from southern Yemen.[96] Aid workers said that towards the end of April, aid agencies called on the Houthis to allow an exception to their requirement that staff arriving by plane quarantine for 14 days at or near the Sanaa airport, given that the airport had been the target of airstrikes by the Saudi-led coalition.[97] They said that the Houthis rejected their request for staff to be allowed to quarantine at safer locations.[98]

Aid agencies said that some flights to Sanaa resumed in mid-June, with UN staff quarantined for two weeks in a UN residential compound or other UN premises and non-UN staff quarantined in their organizations’ premises.[99]

Blocking Aid Group Staff from Moving Within Yemen

Aid workers told Human Rights Watch that the Houthis, without providing reasons, regularly refused to grant their agency’s staff travel permits to move within Yemen, including staff monitoring the distribution of aid, which severely delayed or blocked aid projects.[100] They said the Houthis regularly demanded that their agencies change the nature of their projects’ work or that they provide them with confidential information, including aid recipients’ names, to obtain final approval to travel.[101] They said these impossible demands denied critical aid to people in need and affected the quality of their projects.

Said one aid worker: “It’s very simple; we can’t reach communities where people are dying.”[102] Another said that the Houthis had denied international staff – who had been through quarantine after arriving in the country in April – permission to reach healthcare centers trying to respond to Covid-19.[103] A third said that for half a year in late 2019 and early 2020, the Houthis regularly denied medical staff from their agency in charge of transporting and administering urgently needed specialized medication permission to go to health facilities where their organization was working, and instead insisted the staff go to other facilities to carry out work for which they were not qualified.[104] Another said that throughout 2019 and 2020, the Houthis had denied all international staff permission to travel to areas the Houthis deemed too sensitive, without providing any further explanation.[105] Finally, a former Yemeni aid worker said that in 2018 and 2019, the Houthis regularly took between three and seven days to approve a 30-minute car journey from Sanaa to nearby project sites, which significantly affected the efficiency of her agency’s work.[106]

The UN reported that in the second half of 2019, aid groups “faced complete movement bans, sometimes imposed for months and often as punitive measures … for not complying with arbitrary requests and directives.” Over 750 such incidents were recorded just in the first four months of 2020.[107] Donors monitoring negotiations this obstacle, which had been in place since at least 2018, said in May there had been “no progress.”[108]

In January 2020, the UN Panel of Experts on Yemen reported that aid agencies “had been denied access to certain areas or denied travel authorization because they had refused to share information on beneficiaries or personal information about their national staff.”[109]

Blocking Supplies from Entering by Air, Sea, or Road and Taxation of Supplies

A senior aid worker said that the Houthis stopped aid supplies from entering the country by plane in early March, although some supplies – including for the Covid-19 response – have been allowed to enter since about May 20. The aid worker also said the Houthis introduced a two-week Covid-19-related quarantine system at some point in mid-March for all aid supplies entering Hodeida port, although the Houthis did not explain why supplies would need to be held for two weeks to prevent the spread of Covid-19.[110]

However, according to the UN, as of late June Houthi authorities in Hodeida port had refused to release over 165 containers belonging to the World Health Organization (WHO).[111] An aid worker said each container had almost 70 cubic meters of medical supplies, that as of early September they were still in the port and that the authorities had used some of the shipments as bargaining chips in negotiations relating to the lifting of other aid obstacles.[112] The aid worker said between early July and early September, the Houthis blocked a further 97 WHO containers that had arrived at the port, but that at some point in late August or early September the Houthis authorized 118 of the containers to leave while blocking the rest.[113] The aid worker also said that between early June and early September a “massive shipment” of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) for the Covid-19 response had been stuck in the port.[114]. According to a donor official, the Houthis have blocked the WHO containers because they want the WHO to contract a transport company connected to the Houthis to distribute them, instead of using the less costly WFP arrangements.[115] The aid worker also said that the Houthis required the WHO to pay US$6,000 a day to rent a warehouse to store shipments in Hodeida port and that in early September the Houthis gave the WHO a bill for $650,000, a practice another aid worker said was similar to the Houthis’ refusal to allow aid groups to import their own vehicles from Djibouti, forcing them to rent them at exorbitant rates of between $700 and $1,000 a day from local businesses.[116]

Another senior aid worker said that the 14-day quarantine period was causing unnecessary delays in Covid-19-related supplies reaching aid group warehouses.[117]

In early June, the UN reported that “cargo movements along the south-north supply pipeline [within Yemen] have been impacted by long delays, harassment and irregular taxes and fees.”[118] In late August, an aid worker confirmed this was still the case.[119] This echoes identical reports from October and December 2019.[120]

After six months of pressure from the UN, independent aid groups, and donors, in February 2020 the Houthis said they were dropping their proposal for aid groups to pay a 2 percent tax on each aid and development project to help finance the running of SCMCHA.[121] The proposal had paralyzed a number of projects providing nutritional supplements to 300,000 pregnant women and nursing mothers and children under five.[122] The donor aid monitoring group said in May that some officials said they might reintroduce the demand if the Houthis’ financial situation continued to deteriorate.[123] Three other aid workers said that the authorities regularly informally attempted to extract money from aid groups.[124]

According to an aid worker, throughout 2019 the Houthi authorities regularly blocked dozens of cargo trucks in various locations, in some cases for over 200 days, which rendered some of the cargo, including food, unusable.[125]

Violence Against Aid Groups

The UN reported that “violence against humanitarian personnel, assets and facilities increased sharply during the second half of 2019 [with] more than 70 percent of incidents attributed to authorities in northern Yemen.” Aid agencies reported “583 incidents between January 2019 and April 2020 … including killing and assault, arbitrary detention, arrests, harassment, threats and intimidation, theft of and attacks on assets and armed occupation of humanitarian premises.”[126]

In January 2020, the UN Panel of Experts on Yemen reported that “cases involving the use of violence and coercion at aid distribution points increased in 2019.”[127] The Panel of Experts said it investigated three cases “involving violence against humanitarian workers at distribution points in order to influence or control distribution.” The panel also said it investigated five cases of humanitarian workers being arrested and detained. [128]

An aid worker said that staff at their agency had faced many cases of violence and intimidation by Houthi officials and fighters in 2019, including a case in which Houthi fighters raided a distribution site and threatened aid workers to obtain aid, which resulted in the suspension of aid distribution to highly vulnerable people.[129] Another aid worker said that a number of aid agency staff left Yemen in 2019 after Houthi officials beat, detained, or threatened to arrest them.[130] Two aid workers told Human Rights Watch that at times their work in 2019 had been “paralyzed” or that they had “self-grounded” due to raids by the authorities on their compounds or other mistreatment of staff.[131]

Diversion of Aid

There have been several reports about Houthi authorities diverting aid since 2018.

An investigation by the Associated Press, published on December 31, 2018, found that “factions and militias on all sides of the conflict [had] diverted [food aid] to front-line combat units or sold it for profit on the black market,” including the Houthis and to a lesser extent forces fighting for the Yemeni government.[132] The investigation quoted a former Houthi education minister as saying that the Houthi authorities had diverted 15,000 food baskets a month in 2018 from the education ministry and sold them in the black market or used them to feed frontline soldiers.[133]

Shortly after the Associated Press’s report, the WFP said that its own investigation had found “evidence of trucks illicitly removing food from designated food distribution centers” in Houthi-controlled areas as well as fraud by a local food aid distributor connected to the Houthis’ education ministry.[134] It also said that intended food aid beneficiaries had told WFP they had never received their food.[135]

In June 2019, the WFP said that there was “serious evidence” that the Houthis had diverted food supplies in Sanaa and other Houthi-held areas, citing a third of intended beneficiaries who said they had never received their food and 33 specific cases in which food had been misappropriated. WFP said that the Houthis failed to cooperate with WFP to understand what had happened, in contrast to the attitude of the Yemeni authorities in the south when WFP raised similar concerns there.[136]

In January 2020, the UN Panel of Experts on Yemen reported that while investigating three incidents involving violence against aid agency staff at aid distribution points in 2019, it found evidence that in one case “humanitarian assistance items were also looted, and in another they were diverted.”[137] According to an aid worker, staff of a Houthi-run ministry that receives significant UN funding interfered with aid distribution in numerous ways in 2019, including by looting aid at distribution points and elsewhere.[138] The aid worker also said that they had received “countless reports from beneficiaries and others relating to the diversion of aid both in the north and the south,” including eyewitness accounts from a donor and an aid worker that other aid workers were “taking food from a distribution site and loading it into pickup trucks instead of distributing it.”[139]

In May 2020, Human Rights Watch spoke with a Yemeni healthcare worker in Marib who said that, “according to my contacts, Houthis looted aid trucks and confiscated electronic equipment that was supposed to come to Marib.”[140]

III. Obstruction of Aid in Southern Yemen

Since 2018, different parts of southern Yemen have been controlled by the Yemeni government and the Southern Transitional Council (STC). The Yemeni government maintains control of the day-to-day bureaucracy, including in areas such as Aden, which the STC military controls.[141] This includes the Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation, which regulates aid agencies’ presence and operations in the south at the central and local levels.[142]

All aid agencies said that during the first half of 2020, the Yemeni government interfered less with aid agencies’ work than the Houthis, but that they nonetheless faced frustrating bureaucratic obstacles that significantly delayed and at times blocked their work, especially at the central level in Aden.[143] They said these obstacles had increased between June and August, that some of them were due to political dynamics between ministries slowing down approvals of aid projects and travel permits, and that overall the restrictions have prevented millions of Yemeni from receiving timely assistance.[144] Aid agencies also say that conflict dynamics in the south have created a generally dangerous security environment for their staff that has also disrupted some aid supplies and projects.[145]

The UN humanitarian chief, Mark Lowcock, informed the UN Security Council in late July that in the south, the UN had “serious concerns, with an uptick in violent incidents targeting humanitarian assets, and local authorities adding new bureaucratic requirements for aid agencies.”[146] In mid-August, his deputy, Ramesh Rajasingham, told the council that the UN was “concerned by … bureaucratic impediments [to aid]” and that “in recent weeks aid supplies have been detained at checkpoints at least twice for more than 24 hours.”[147] In January 2020, the UN Panel of Experts on Yemen reported that the Yemeni government had held nine medical and nutritional shipments at the port of Aden for between 16 and 169 days, but that the government did not explain the reason for the delays. The panel concluded that this amounted to “obstruction of the delivery of humanitarian assistance.”[148]

In June, Human Rights Watch obtained an up-to-date aid agency overview document detailing a wide range of obstacles to aid in north and south Yemen. In the south, these included long delays in obtaining movement permits, interference in or denial of needs assessments, intimidation of project staff, attempts to manipulate aid group data, and a risk of aid diversion, among others.[149] An aid worker said that officials in Hadhramaut have insisted that the agency she works for hand over some of the food intended for poor families and displaced persons before her agency can distribute the rest and that on other occasions officials have insisted on distributing other agencies’ aid themselves but that the aid never reached the intended recipients.[150]

In July, aid workers said that Yemeni government officials were in contact with those in the north and were copying the same kinds of access constraints that the Houthis had been using.[151] They said that aid agencies were increasingly facing a range of problems including delays in signing principal agreements (PAs) and sub agreements (SAs) due to attempts to insert clauses threatening NGOs’ independence, requests for bribes and copies of beneficiary lists, and delays in visa approvals for staff seeking to enter the country.[152]

In May, an aid worker told Human Rights Watch that the Yemeni government authorities were pressuring his aid agency to share the names of people taking part in training sessions or benefitting from certain types of projects.[153] In July, an aid worker said that Yemeni government authorities in two governorates had asked a number of agencies to share beneficiary lists with them before aid distribution took place.[154]

In June, the UN also reported that aid groups “continue to report delays and problems at checkpoints.”[155] Several aid agencies said that on a number of occasions, the STC delayed or detained at checkpoints their Yemeni staff originating from Houthi-held areas, especially after the STC’s takeover of Aden in August 2019, and that for some time agencies decided to suspend movement of such staff in the south, which reduced their ability to manage their projects.[156] An aid worker also said that on a number of occasions in 2019, local authorities blocked the transportation of medical supplies, including at least one incident in which local officials raided and stole aid supplies from aid agency warehouses.[157]

Another aid worker said that in 2019 and the first half of 2020, their organization faced a number of Yemeni government obstacles in various parts of the south that had a “pretty bad overall blocking effect” and led to a “constant feeling of insecurity regarding whether the projects will have to stop.”[158]

Several aid workers said that they thought the only reason the obstacles were not more systematic and like those in the north was because there was less centralized control in the south, making it harder to monitor aid agencies and enforce rules dictated at a central level.[159]

Another aid worker said that it was easier to get the Yemeni government to sign SAs in the south compared to the north.[160] The UN says that only 70 percent of such agreements submitted in 2019 had been signed by the end of the year and that as of late-August 2020, aid groups were waiting for the authorities to approve about 30 projects.[161]

In late July, aid agencies said that they and the UN were negotiating with the authorities on a new standard PA, but that the authorities were trying to include problematic clauses that would unduly interfere with aid agencies’ work.[162]

Two other aid workers said that in the first few months of 2020, the authorities had refused to sign a PA, but continued to negotiate with their organization on SAs and that when these got stuck, the authorities nonetheless allowed related supplies to enter the country and gave staff permission to travel to project sites where local officials allowed them to work.[163]

Two agencies and a donor also said that many agencies had struggled in 2019 and early 2020 to obtain visas for their staff for the south, although they said some aid groups had found it easier beginning in May, when flights resumed from abroad into Aden.[164] A number of aid agencies said it had taken a long time to reach agreement with the authorities in quarantine arrangements for staff arriving from abroad since May and that the southern authorities imposed bureaucratic requirements that delayed newly arriving staff from then traveling overland to Houthi-held areas.[165]

In addition to these access constraints, two senior aid workers said that aid agencies in southern Yemen do not carry out sufficient context analysis to determine where, at any given time, it should be possible to carry out aid projects without risking staff safety. They said that the result is a very conservative approach, including the requirement that any aid worker movement outside of Aden involve a military escort, which is normally a last resort used in the most dangerous contexts. They said that this has resulted in less aid projects than should be the case.[166]

IV. Concerns about UN-led Response to Aid Obstacles since 2015

Human Rights Watch spoke with seven aid officials and two donor government officials about their concerns relating to the humanitarian community’s response to long-term obstacles to aid in Yemen. The United Nations’ response included efforts by senior officials who were sent to Yemen to try to address the challenges.[167] One proposal that had the support of many aid workers from UN agencies and other humanitarian organizations was the creation of an independent UN review into aid operations since 2015 in the north, which many consider was badly handled, as well as a review of the humanitarian community’s response in the south.[168]

Aid officials and donors raised the following specific concerns about the humanitarian community’s response to aid obstacles since 2015:

- A failure to study and understand who wields power at central, regional and local levels in Yemen to adapt negotiation efforts;

- Focusing negotiation efforts on newly arrived officials at the central level, in Sanaa, instead of on officials with decades of experience working with aid agencies at a more local level;

- A failure to engage with key civilian officials, including in the Houthi Supreme Council for Management and Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs and International Cooperation (SCMCHA) and officials in the Department of Foreign Affairs;

- A failure to engage more proactively with national security and military officials;[169]

- Involvement of senior UN officials and donor countries in humanitarian negotiations, negatively affecting aid agencies’ relationships with the authorities;

- Conceding to a series of demands relating to the control of aid projects that encouraged the authorities to seek ever-greater control;

- Failing to adopt a unified aid agency approach to pushing back on obstacles and instead letting individual agencies fight their own battles;

- A lack of strategic analysis until 2019 of factors contributing to specific types of aid obstacles;

- Channeling vast amounts of money, including salary incentive payments and other support, to clearly corrupt ministries without sufficient transparency to avoid multiple agencies supporting the same person or department and without conditions attached, such as independent monitoring and requiring measurable efficiency improvements;[170]

- Allowing too many projects to be controlled by the Ministry of Health instead of directly funding more aid groups capable of carrying out emergency response services;

- Too readily financially supporting SCMCHA and its predecessor agency, National Authority for the Management and Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs and Disaster Recovery (NAMCHA), and failing to propose an alternative to the framework used by SCMCHA to regulate aid agencies, known as Decree 201, to help secure aid agency independence and impartiality;

- Failing to transparently investigate and report on allegations of UN agencies’ complicity in aid diversion, including proactively reporting on diversion of UN salaries and incentive payments to Yemeni officials.

In light of the wide-ranging concerns about the humanitarian community’s response to aid obstruction in Yemen, the UN Human Rights Council should mandate the UN-established Group of Eminent Experts (GEE) on Yemen to conduct an independent and comprehensive review of the extent of the obstruction of aid in north and south Yemen since 2015 and the humanitarian community's response to the obstruction. The UN Security Council’s Yemen Sanctions Committee should also mandate the Panel of Experts on Yemen to conduct such a review. OCHA should work closely with the GEE and the Panel of Experts on Yemen, and the resulting reports, to be presented to the Security Council and the Human Rights Council at its 47th session in June 2021, should make concrete recommendations for the steps OCHA, other UN agencies and officials and the broader humanitarian community should take to more effectively respond to the aid obstacles.

According to UN procedures, within 15 months of the UN classifying a humanitarian crisis as a Level 3 emergency, the UN should undertake a review of the UN’s response to the crisis and produce a report within 15 months.[171] The UN declared a Level 3 emergency in Yemen in 2015, but so far has not carried out an Inter-Agency Humanitarian Evaluation (IAHE).[172] IAHEs are wide-ranging, are not limited to a specific topic, and “are not an in-depth evaluation of any one sector or of the performance of a specific agency.”[173] An IAHE of the Yemen response would be useful, but it should be complemented by a separate independent and comprehensive review of the extent of the obstruction of aid in north and south Yemen since 2015 and the humanitarian community's response to the obstruction.

V Collapse of Donor Support to Yemen

In late July 2020, the United Nations humanitarian chief, Mark Lowcock, informed the UN Security Council that Yemen’s aid operation, which focuses primarily on the north, was, “frankly, on the verge of collapse,” and that aid agencies had “already seen severe cuts to many of [their] most essential services.”[174]

Between 2015 and 2019, international donors gave the UN-led aid response in Yemen US$8.35 billion, including $3.6 billion in 2019 that reached almost 14 million people each month with various types of aid, up from 7.5 million people in 2018.[175] An aid worker said that in 2019 in the north, 80 percent of donor funds went to UN agencies, which mostly subcontracted to Houthi-run ministries, including through significant amounts of financial and other support to the Ministry of Education, while non-UN aid groups received the rest.[176]

However, by the end of May, aid agencies had received only $525 million of the $3.4 billion they had requested for the year.[177] At a humanitarian donor conference in early June, 31 donors pledged $1.35 billion for the second half of the year.[178] According to a senior UN official, this included $225 million for emergency food aid mostly in southern Yemen that the United States had already pledged – but not yet provided – in May.[179] It also included $500 million from Saudi Arabia, a major party to the conflict, almost half of which would be administered by the country’s government-run relief agency.[180] Another major party to the conflict, the United Arab Emirates, donated about $400 million in 2019, but pledged nothing in June.[181] By August 28, aid agencies had received $812 million of the $3.4 billion originally sought for the year.[182]

In June, the UN said the drop in donor funding was due in part to “the increasingly restrictive operating environment in the second half of 2019” which “made it difficult to assure donors that aid was being delivered in accordance with humanitarian principles.”[183]

Citing “unacceptable interference” in aid operations in northern Yemen, the United States said on March 27, 2020 that it would cut $73 million to non-UN aid groups providing primary health care and other services, with exceptions for certain lifesaving activities to be defined on a case-by-case basis.[184] The funding cut immediately affected almost 750,000 people.[185] In August, six international aid groups said the exceptions were “too narrow to deliver an effective response,” citing examples of how food, healthcare, and hygiene and sanitation projects had been affected.[186]

On April 9, the World Food Program (WFP) announced it would also halve food aid to 8.5 million people in northern Yemen, also citing aid obstruction. This echoed a mid-2019 suspension of food aid for two months after the authorities refused to let the WFP record food aid recipients’ biometric data to ensure that food reached intended recipients.[187] Negotiations with the Houthis around biometric data collection, which began in mid-2018, continued until the end of April 2020 when the authorities said the WFP could carry out the first stage of a pilot project in three districts of Sanaa city.[188] However, three aid workers said that since then the Houthis have obstructed progress, only allowing some training, the establishment of some committees at the local level and some data collection relating to particularly vulnerable people in need of food aid.[189] A donor official said the US would be unlikely to fund full food rations until the issue around biometric data collection had been resolved.[190]

In August, six international aid groups issued a letter saying that while they “still contend with constraints on humanitarian access and the risk of aid diversion, the most significant challenge to sustained life-saving humanitarian action today is the severe shortfall in funding” and called on the US to “lift [its] … suspension of humanitarian assistance to northern Yemen … and [to] restore funding wherever partners can operate in a principled manner.”[191] They warned that the suspension would force some aid groups to close life-saving programs and offices and possibly their entire presence in the north.[192]

Aid agency officials described in detail to Human Rights Watch their repeated attempts in late 2019 and in early 2020 to call on the authorities to end the aid obstruction. These included formal letters that said that without progress, donors would likely cut funding.[193] A senior UN official raised similar concerns during a briefing to the UN Security Council in November 2019.[194] Donors also wrote to the authorities in the north and south on May 7, setting out their ongoing concerns.[195]

A donor country official with close knowledge of the obstruction of aid told Human Rights Watch in June that the situation was “absolutely unsustainable,” meaning donors could not continue business as usual.[196]

In July, the UN reported that “the Yemen humanitarian response, including for Covid-19, remains hugely underfunded, risking an increase in the spread of Covid-19 and jeopardizing the ability of humanitarian partners to respond.”[197]

The funding crisis has had a dire impact on the Yemeni people.

As noted above, the US funding cuts in March which halved assistance to 9 million people and in late August the UN warned that “further [food] reductions are expected” in north and south Yemen, affecting another 5 million people.[198]

In April, aid agencies suspended projects strengthening access to health services in seven governorates, “depriving 1.3 million people of access to life-saving care.”[199] In April and May, the WHO stopped incentive payments to over 1,800 individual healthcare workers affecting at least 2 million people; to 110 emergency medical teams putting 1.6 million people at “higher risk of dying due to a lack of surgical services”; and to 4,000 health workers “supporting preparedness and response, affecting 18 million people.”[200] In April, a major agency stopped health services in 51 facilities in northern Yemen and in a further 10 in the south in July, “depriving 1.8 million people of regular access to healthcare services.”[201]

By mid-June, the UN said it had closed 75 percent of its key programs, most of them “critical” in tackling Covid-19,[202] which it said has “put the lives of millions … on the line.”[203]

In late August, the UN warned of a range of further imminent cuts affecting almost 1 million displaced Yemenis, about 100,000 refugees and migrants and almost 400,000 survivors of gender-based violence.[204]

VI. Fuel Restrictions Exacerbating Humanitarian Crisis

Since June 2020, a dispute between the Houthis and the Yemeni government about the use of tax revenues from fuel arriving at Hodeida port has blocked numerous commercial vessels carrying fuel off the coast .[205] The United Nations said in early July that the renewed “fuel crisis … threatens access to food, hospital operations and water supplies which are fuel-dependent and crucial to preventing virus transmission and to the response, and presents a further obstacle to people seeking treatment.”[206]

Similar crises in April and September 2019 triggered 60 percent spikes in prices and fuel shortages that disrupted health, water, and sanitation services for several weeks.[207] Yemen, and humanitarian operations in the country, previously faced fuel crises, including in 2015 due to the Saudi-led coalition’s blockade and in 2017.[208]

Fuel imported by commercial vessels is used by the public and private sector in Yemen, including humanitarian agencies.[209] Under a November 2019 agreement, which helped end the September 2019 fuel crisis, the Houthis and the Yemeni government said that commercial fuel companies would pay fuel import taxes and customs fees imposed by both sides into an account at the Central Bank in Hodeida, and they committed to use these funds to pay public sector workers’ salaries in Houthi-controlled areas.[210]