When the novel coronavirus began spreading, the shared fate of the globe’s seven billion people came sharply into focus. The virus could infect anyone; leaving anyone unprotected meant making everyone vulnerable. But any hope of solidarity was soon undermined by the harsh reality of our deeply unequal global economic system. Many people were hit not just by the virus, but by the economic devastation it has wrought, while others—individuals or states—were able to use the vast disparities in resources to build protective bubbles around themselves.

The numbers are stark: For hundreds of millions of workers, last year was one of the worst in history, costing them US$3.7 trillion in lost earnings. At the same time, the world’s 2,200-plus billionaires saw their wealth grow by $1.9 trillion.

Job losses were concentrated in low-wage industries and disproportionately affected women and people of color, with devastating effects on human rights. Hundreds of millions were pushed into poverty, experienced hunger, or faced risk of eviction. People who were struggling with poverty before the pandemic sank even deeper into economic distress. With schools closed and families desperate for income, millions of children were deprived of their childhood as they had to start working to support their parents.

Job and income losses have been most acute where governments were already failing to guarantee the right to an adequate standard of living and social security for all. The pandemic has exposed the human costs of underfunded healthcare systems, unaffordable or inadequate housing, precarious employment, and weak or nonexistent systems of social security. From Nigeria to Lebanon to the United States, Human Rights Watch documented how lower-income households, especially, saw their economic and social rights violated as governments failed to provide a safety net. The United Kingdom, one of the world’s wealthiest countries, was failing to ensure everyone’s right to food even before the pandemic hit. When schools closed in the UK, children from low-income families, who had relied on schools for their main daily meal, were left without adequate government support to ensure they had enough to eat.

Government Response

If there is a bright spot to this crisis, it is that many governments have enacted new, sometimes unprecedented measures to protect people, in some cases reversing decades of neglecting social spending that hurt human rights. The International Monetary Fund even pledged to make confronting inequality a pillar of economic recovery.

But the increase in spending does not necessarily result in increased protection of the most vulnerable. One in 4 households in the US experienced food insecurity last year, the first year of the pandemic. The first round of US stimulus relief, the CARES Act, included $135 billion in tax relief for the top one percent of US taxpayers, but nothing for the millions in the informal economy or those who are undocumented, even though they are some of the most vulnerable people in the country. It also appeared to direct relief to large business owners with little or no discernible benefit for the workers.

Many governments, including some that received billions of US dollars in loans from the IMF, such as Egypt and Nigeria, have failed to include millions of people in poverty in Covid-19 relief measures and have not been adequately transparent about how they used pandemic funds. The IMF has also already fallen back on bad habits of urging governments to cut spending and overly rely on taxes from low-income groups.

The disparities in governments’ ability to prop up their economies means that inequality is expected to worsen. Wealthy countries are able to weather the economic storm far better than low-income countries, which have had little fiscal and monetary flexibility during the crisis. On average, advanced economies have spent nearly 20 percent of annual GDP on fiscal stimulus, 10 times the two percent of annual Gross Domestic Product (GDP) that low-income countries have spent. Low-income countries have also had limited access to vaccines because wealthier countries bought up a large share of global supply.

Wealthy countries should help ensure equitable access to the vaccine by temporarily waiving intellectual property protections so that more countries are able to manufacture it. That will help ensure that everyone has a fair shot to recovery and that developing economies get the assistance they need. If they do not, the pandemic will persist longer, and the global divide will deepen.

The Fraught Path Ahead

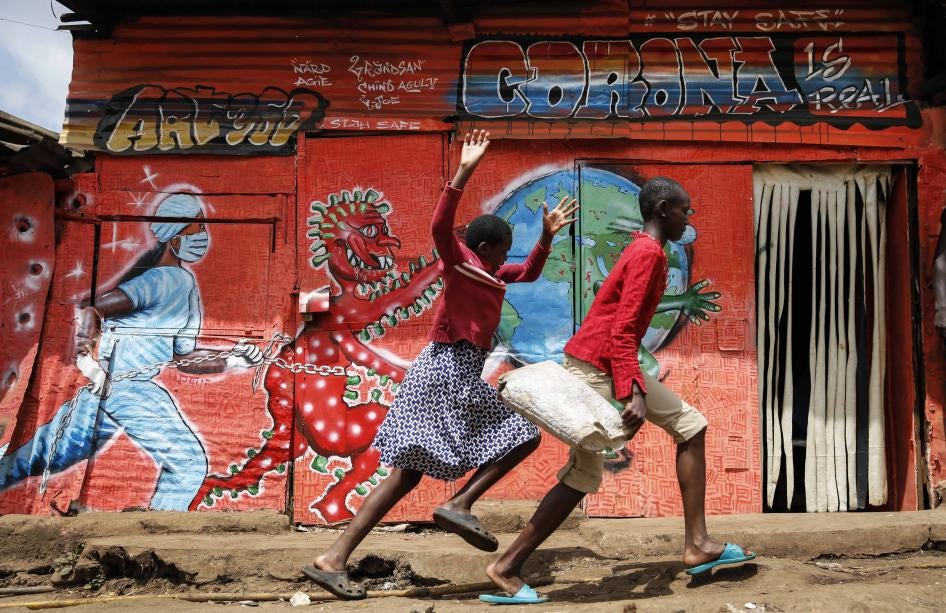

The Covid-19 pandemic has exposed and exacerbated poverty and inequality globally and has drawn attention to the impact on people’s economic and social rights. The deterioration of public services and inadequate or nonexistent safety nets alongside pockets of wealth fueled discontent before the pandemic; in some countries, that discontent has sharpened as hunger and poverty have worsened with the pandemic.

In Nigeria, which is facing its worst economic recession in four decades, protesters demonstrating against police brutality have also drawn attention to economic mismanagement and corruption. As a result, the IMF warned that surging unemployment and poverty during the pandemic are fueling social instability. In Lebanon, despite lockdown restrictions, thousands of people have taken to the streets to protest rapidly deteriorating standards of living and an almost nonexistent social safety net.

If the economic despair and social unrest indicate that the existing economic structures are not working for the majority of humanity—even before the pandemic nearly half the world lived on less than US$5.50 a day—there is an urgent need to identify possible alternatives. It has become increasingly clear that tinkering at the edges won't protect people’s rights.

Argentina and Bolivia have started the search for alternative ways to address budget shortfalls, including by introducing taxes on the wealthiest people to pay for relief measures.

Inequality is the long-festering problem that this crisis has so clearly exposed. The post-pandemic recovery should focus on improving social protection for all and rebuilding employment. It is essential to rethink skewed policies and approaches that take resources away from those who need them the most—whether through abusive austerity, revenue collection that disproportionally burdens those with low incomes, or other measures—to the benefit of those who do not, and build more rights-respecting economies that work for everyone.