Summary

I’ve been chained for five years. The chain is so heavy. It doesn’t feel right; it makes me sad. I stay in a small room with seven men. I’m not allowed to wear clothes, only underwear. I have to go to the toilet in a bucket. I eat porridge in the morning and if I’m lucky, I find bread at night, but not every night…. It’s not how a human being is supposed to be. A human being should be free.

—Paul, man with a psychosocial disability chained in a faith healing institution, Kenya, February 2020

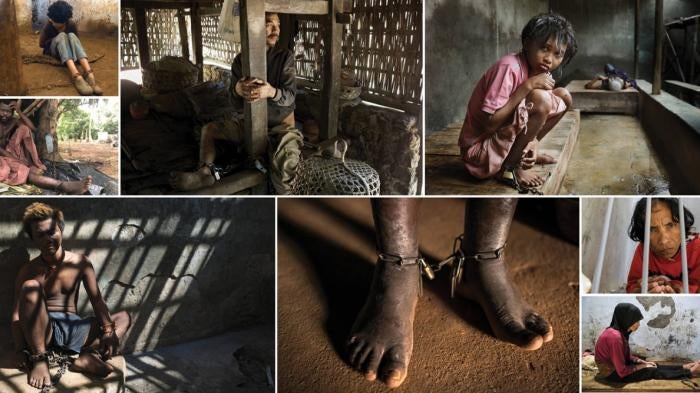

Around the world, hundreds of thousands of men, women, and children with mental health conditions have been shackled—chained or locked in confined spaces—at least once in their lives.

Many are held in overcrowded, filthy rooms, sheds, cages, or animal shelters and are forced to eat, sleep, urinate, and defecate in the same tiny area. This inhumane practice—called “shackling”—exists due to inadequate support and mental health services as well as widespread beliefs that stigmatize people with psychosocial disabilities.

Globally, an estimated 792 million people or 1 in 10 people, including 1 in 5 children, have a mental health condition. Depression, which is the leading cause of disability, is reported to be twice as common in women than men.[8] Women, given the high incidence of sexual violence they suffer, are also disproportionately affected by Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).[9]

Yet, mental health draws only limited government attention. On average, countries spend less than 2 percent of their health budgets on mental health. About 80 percent of people with disabilities, including people with psychosocial disabilities, live in middle or low-income countries where it is often challenging to access healthcare, particularly mental health care.

The cost of mental health services can be prohibitive. More than two-thirds of countries do not cover reimbursement for mental health services in national health insurance schemes. Even when mental health services are free or subsidized, the distance and transport costs are a significant barrier.

Human Rights Watch found evidence of shackling across 60 countries across Asia, Africa, Europe, the Middle East, and the Americas. This report includes field research and testimonies collected by 16 Human Rights Watch researchers working in their own countries, including Afghanistan, Burkina Faso, Cambodia, Ghana, Indonesia, Kenya, Liberia, Mexico, Mozambique, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Palestine, Russia, the self-declared independent state of Somaliland, South Sudan, and Yemen.

Existing mental health services are often under-utilized or do not comply with international human rights standards because of limited understanding and awareness of mental health. In many countries around the world, there is a widespread belief that mental health conditions are the result of possession by evil spirits or the devil, having sinned, displaying immoral behavior, or having a lack of faith. Therefore, people first consult faith or traditional healers and often only seek medical advice as a last resort.

Despite being commonly practiced around the world, shackling remains a largely invisible problem as it occurs behind closed doors, often shrouded in secrecy, and concealed even from neighbors due to shame and stigma.

Families who struggle to cope with the demands of caring for a relative with a psychosocial disability may feel they have no choice but to shackle them. People with real or perceived psychosocial disabilities can be shackled for days and weeks, to months, and even years.

Human Rights Watch research across 60 countries found people with real or perceived psychosocial disabilities are arbitrarily detained against their will in homes, state-run or private institutions, and traditional or religious healing centers.

In countries where people believe mental health is a spiritual issue and robust mental health services are lacking, private institutions and faith-healing facilities flourish.

In China, about 100,000 people are shackled or locked in cages in Hebei province alone, near Beijing. In Indonesia, 57,000 people with mental health conditions have been in pasung (shackles) at least once in their lives. In India, thousands of people with mental health conditions were found chained like cattle in the state of Uttar Pradesh.

In Nigeria, Human Rights Watch visited 28 state-run and private facilities between 2018 and 2019, across which a few hundred people were arbitrarily detained, and where people were regularly chained or shackled. In Nigeria, amongst the people Human Rights Watch interviewed, the youngest child chained was a 10-year-old boy and the oldest person was an 86-year-old man. In Guatemala, hundreds of children with psychosocial or intellectual disabilities were tied to furniture or locked in cages in orphanages and institutions. In Morocco, the government released over 700 people chained in one shrine alone, about 50 kilometers from Marrakesh in the country’s southwest.

In one case, a man with a psychosocial disability spent 37 years chained in a dark, sweltering cave in the mountains in Wadi Al-Sabab, Saudi Arabia.

In social care institutions, run by nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) or traditional or religious healing centers, families often use false pretenses to get relatives to enter an institution, or simply provide no explanation at all. It is typically an administrative process and does not contain any provisions for judicial oversight. People end up living shackled in institutions for long periods because their relatives do not come to take them home and the institution has nowhere to send them.

While the conditions of confinement may vary based on the method of shackling, location, and country, one thing remains the same: people who are shackled are forced to live in extremely unsanitary and degrading conditions.

Personal hygiene is a serious problem since people who are chained often do not have access to a toilet. As a result, they urinate, defecate, eat, and sleep in a radius of no more than one to two meters. In some instances, people are provided with a small bucket in which to urinate and defecate, but these are only emptied once a day leaving a putrid smell in the room for most of the day. And women and girls are not supported to manage their menstrual hygiene, for example through the provision of sanitary pads.

The nature of shackling means that people live in very restrictive conditions that reduce their ability to stand or move at all. People who are shackled to one another are forced to go to the toilet or sleep together. In a privately-run social care institution in Russia, staff regularly brought people with psychosocial disabilities to the dining hall chained to each other and forced them to eat in handcuffs.

Shackling impacts a person’s mental as well as physical health. A person who is shackled can be affected by post-traumatic stress, malnutrition, infections, nerve damage, muscular atrophy, and cardio-vascular problems. In Mexico, for example, children with psychosocial disabilities in one institution were fully wrapped in bandages, duct tape or clothing, like mummies.

Shelter was a major concern for people shackled outdoors without a roof over their heads, protection from the sun or rain, and with constant exposure to mosquitoes and pests. In prayer camps and institutions in some countries, many interviewees spoke of persistent, gnawing hunger from forced fasting or inadequate food, and many looked emaciated.

People with psychosocial disabilities, including children, who are shackled in homes or institutions are routinely forced to take medication or subjected to alternative “treatments” such as concoctions of “magical” herbs, vigorous massages by traditional healers, Quranic recitation in the person’s ear, and special baths.

Carlos, a man with a psychosocial disability who had been chained and treated against his will in faith healing institutions in Mozambique, said:

I’ve been tied many times and given bitter medicines through the nose…. They give you roots, leaves as medicine. Their treatment was always unsuccessful. My mother and father would come and take shifts. One time I escaped with the rope tied to a log. They caught me and I pleaded with my mother to bring me home, I really suffered in that place.[10]

Human Rights Watch documented physical and sexual violence against people with psychosocial disabilities who were shackled in homes and institutions. Persons with psychosocial disabilities experience physical abuse if they try to run away from institutions or don’t obey the staff.

In many institutions visited by Human Rights Watch, male staff would enter and exit women’s wards or sections at will or were responsible for the women’s sections, including at night, which puts women and girls at increased risk of sexual violence, as well as subjects them to a constant feeling of insecurity and fear. In many healing centers, in countries such as Nigeria and Indonesia, men, women, and children were chained next to each other, leaving them no option to escape if they encountered abuse from staff or other chained individuals. In Nigeria, boys as young as 10 were chained together in rooms with adult men, leaving them at risk of abuse.

While countries are increasingly starting to pay attention to the issue of mental health, the practice of shackling remains largely invisible. There are currently no coordinated international or regional efforts to eradicate shackling. Although it is noteworthy that some governments have put in place measures to tackle the practice of shackling, their laws and policies are not always effectively implemented, and on-the-ground monitoring remains weak overall.

Of the 60 countries where Human Rights Watch found evidence of shackling, only a handful have laws, policies or strategies in place that explicitly ban or aim to end shackling of people with mental health conditions.

Human Rights Watch calls on the international community and national governments to ban shackling, adopt measures to reduce stigma against people with psychosocial disabilities, and develop adequate, voluntary, and community-based mental health services.

Ridha, a family member with relatives shackled in Oman, said: “It’s time for governments to step up so that families aren’t left to cope on their own.”

With the right kind of support, people with mental health conditions can live and thrive in their communities. In Tanzania, Malaki, a boy with an intellectual disability was chained to a pole by his family to ensure he remained safe in his home in Nyarugusu refugee camp in Kigoma province in Tanzania in 2017. When the Special Olympics team had Malaki released, he got the opportunity and training to play football. Malaki’s story helped shape his community to be more inclusive and accepting. Malaki went from playing football in the Nyarugusu camp in Tanzania to the 2019 Special Olympics World Games in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates.

Terms

Child: The word “child,” “boy,” or “girl” in this report refers to someone under the age of 18. The Convention on the Rights of the Child states that under the convention, “a child means every human being below the age of 18 years unless under the law applicable to the child, majority is attained earlier.”[1]

Disabled Persons’ Organizations (DPOs): Organizations in which persons with disabilities constitute the majority of members and the governing body and that work to promote self-representation, participation, equality, and integration of persons with disabilities.[2]

Institutions: Refers to state-run (unless specified otherwise) psychiatric hospitals, government social care or nongovernmental organization-run residential facilities. Traditional or spiritual healing centers are also considered types of rudimentary institutions.

Legal capacity: The right of an individual to make their own choices about their life.[3] This encompasses the right to personhood, being recognized as a person before the law, and legal agency, the capacity to act and exercise those rights.[4]

Psychosocial disability: The preferred term to describe people with mental health conditions such as depression, bipolar, schizophrenia, and catatonia. The term “psychosocial disability” describes conditions commonly referred to—particularly by mental health professionals and media—as “mental illness” or “mental disorders.” The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities recognizes that disability is an evolving concept and that it results from the interaction between people with impairments and social, cultural, attitudinal, and environmental barriers that prevent their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others. The term “psychosocial disability” is preferred as it expresses the interaction between psychological differences and social or cultural limits for behavior, as well as the stigma that society attaches to people with mental health conditions. [5]

Shackling: Traditionally defined as the practice of confining a person’s arms or legs using a manacle or fetter to restrict their movement, historically used to confine slaves or prisoners. For the purpose of this report, shackling is used in a broader sense to refer to the practice of confining a person with a psychosocial disability using chains, locking them in a room, a shed, a cage, or an animal shelter. See the “Shackling” chapter for a more detailed description.

Traditional or religious healing centers: Refers to centers, generally run by traditional or faith healers who practice “healing” techniques including chaining, recitation of religious texts or songs, fasting, baths, herbal concoctions, and rubbing the body with stones.[6] In some countries, these centers are called prayer camps. They are run by self-proclaimed prophets and are Christian religious institutions not affiliated with other denominations, but with roots in the evangelical or Pentecostal movements, established for purposes of prayer, counseling, and spiritual healing. They are also involved in various charitable activities. Often an extension of the faith healer’s house or situated within the compound of a church, temple, shrine, mosque, or religious school, these sometimes rudimentary centers primarily cater to individuals with alleged spiritual problems such as bewitchment or possession by the devil or jinn (evil spirits); lack of faith; perceived or real mental health conditions; drug use or “deviant” behavior, including skipping school, smoking tobacco or marijuana, being greedy, or stealing. Typically, people in these centers have been placed there by their families or by local police, some forcibly.

Traditional or religious healers: Traditional healers administer therapies based on theories, beliefs, and experiences indigenous to different cultures including ritual and herbal methods of treatment. Islamic faith healers often use Quranic recitations or herbal medicine, including the burning of herbs, as a treatment method.[7] Christian faith healers typically use prayer, religious counseling, fasting, and spiritual healing as treatment methods.

Recommendations

To International Donors and Bilateral Government Donors

- Urge national governments to ban shackling of people with real or perceived mental health conditions and develop adequate, quality, and voluntary community-based support mental health services.

- Support national governments in reducing stigma and discrimination against people with psychosocial disabilities.

- Support national government efforts to develop adequate, quality, and voluntary community-based support and services, including access to housing, education, employment, and mental health services.

- Target support toward community-based support and services, including mental health services. Ensure these programs are gender-sensitive.

- Encourage governments to collect quantitative and qualitative data on the current number of people shackled, the reasons families continue to practice shackling, and examine the support or services they would need to discontinue the practice.

To National Governments in Countries Where Shackling is Practiced

- Ban shackling in law and in policy.

- Comprehensively investigate state and private institutions in which people with mental health conditions live, with the goal of stopping chaining and ending other abuses.

- Ensure that people who have been released from state and private institutions have access to psychosocial support and social services. Children should have access to child psychologists and specialist support services.

- Train and sensitize government health workers, mental health professionals, and staff in faith-based and traditional healing centers to the rights and needs of people with mental health conditions.

- Conduct public information campaigns to raise awareness about mental health conditions and the rights of people with disabilities, especially among alternative mental health service providers and the broader community, in partnership with people with lived experiences of mental health conditions, faith leaders, and media.

- Progressively develop voluntary and accessible community-based support and services, including access to housing, education, employment, and mental health services, in consultation with people with lived experiences of mental health conditions and with the support of international donors and partners. This should include development of psychosocial support services and integration of mental health services in the primary healthcare system.

- Conduct regular, unannounced monitoring visits to government and private social care institutions as well as faith healing centers, with unhindered and confidential interaction with both staff and patients. Findings of these visits, redacted to protect privacy rights, should be publicly reported.

- Establish independent and confidential complaints systems that receive and investigate complaints, including ill-treatment of persons with psychosocial disabilities in institutions.

- Create and carry out deinstitutionalization policies and time-bound action plans, based on the values of equality, independence, and inclusion for people with disabilities. Preventing institutionalization should be an important part of this plan. Governments should include people with disabilities and their representative organizations in developing and carrying out the plans.

- Undertake community support programs and independent and supported living arrangements for people with psychosocial disabilities, particularly those who have been freed from shackling.

- Engage spiritual and religious leaders to challenge discriminatory beliefs and practices related to psychosocial disabilities, and offer education opportunities on mental health and the rights and needs of people with psychosocial disabilities.

- Improve quantitative and qualitative data collection at the local and national levels on the current number of people shackled, the reasons families continue to practice shackling, and the support or services they would need to discontinue the practice.

To the Management of Faith-healing Centers

- Immediately end the use of chaining, nonconsensual fasting, and any form of detention.

- Provide adequate food, shelter, and health services to people with psychosocial disabilities.

- Enable people with psychosocial disabilities to freely enter and leave at will, to refuse treatment, and to seek other services, and ensure that everyone in the camps is always fully aware of this.

- Ensure coordination between mental health professionals and staff at prayer camps to offer mental health services based on free and informed consent.

To Faith-based Organizations

- Publicly denounce the practice of shackling and actively oppose all forms of shackling, including by affiliated leaders and institutions.

- Ensure shackling is not practiced by the organization’s representatives or at holy sites.

- Advocate for the integration of people with psychosocial disabilities in the community.

- Provide training to broader membership, including at grassroots levels, about the rights of people with psychosocial disabilities.

- Provide counseling and other forms of support to people with psychosocial disabilities and their families.

Methodology

In order to show the scale and scope of shackling of people with real or perceived psychosocial disabilities worldwide, Human Rights Watch conducted a study of mental health legislation, relevant policies, and practices across 60 countries around the world.

This report includes research and testimonies collected by 16 Human Rights Watch researchers in their own countries. We worked closely with partner organizations to visit private homes and institutions in Afghanistan, Burkina Faso, Cambodia, Ghana, Indonesia, Kenya, Liberia, Mexico, Mozambique, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Palestine, Russia, the self-declared independent state of Somaliland, South Sudan, and Yemen. Human Rights Watch researchers interviewed more than 350 people with psychosocial disabilities, including those who were shackled at the time of research or had been shackled at least once in their lives, and more than 430 family members, caregivers or staff working in institutions, psychiatrists, psychologists, nurses and other mental health professionals, faith healers, lawyers, government officials, representatives of local nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), including organizations of persons with disabilities, and disability rights advocates. The testimonies were collected between August 2018 and September 2020 through in-person and phone interviews.

In certain cases, people with disabilities and their family members are identified with pseudonyms and identifying information, such as location or date of interview, has been withheld in order to respect confidentiality and protect them from reprisals from family or staff in institutions.

The report also draws on Human Rights Watch’s extensive research on stigma, mental health, and discrimination that people with psychosocial disabilities face around the world, including in Australia, Brazil, Cameroon, Croatia, India, Iran, Kazakhstan,

and Zambia.

In addition to research conducted by Human Rights Watch researchers, pro-bono desk research was conducted by students at the International Human Rights Program at the University of Toronto Faculty of Law and at the Rotman School of Management at the University of Toronto, Canada, as well as by lawyers at Borden Ladner Gervais LLP, Canada, and O’Melveny & Myers LLP in the United States.

The desk research included online search, analyses of national mental laws and policies, and review of relevant literature and domestic and international news reports. Students and Human Rights Watch researchers also conducted phone interviews with activists, representatives of local NGOs, mental health professionals, and journalists. Out of the 110 countries on which we conducted research, we found cases of shackling of people with psychosocial disabilities across 60 countries.

Human Rights Watch also consulted international disability experts at different stages of the research and writing and reviewed relevant domestic and international media reports, official government documents and reports by government-run mental health facilities or institutions, United Nations documents, World Health Organization publications, NGO reports, and academic articles.

While the use of restraints can be seen as a spectrum, this report specifically examines the practice of shackling, the most egregious, archaic, and rudimentary form of physical restraints practiced predominantly in non-medical settings.

The State of Global Mental Health

According to the latest available global estimates, 792 million people or 10.7 percent of the global population has a mental health condition.[11] In countries in crisis or conflict, up to 22 percent or 1 in 5 people have a mental health condition.[12] The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that one in five of the world’s children and adolescents have a mental health condition.[13] Every 40 seconds, someone dies by suicide.[14] Yet, psychosocial disabilities draw only limited government attention.

Gender is a major factor in mental health. Depression, which is the leading cause of disability, is reported to be twice as common in women than men.[15] Discrimination, gender-based violence, socioeconomic disadvantage, income inequality, subordinate social status and the pressure of multiple roles are among the most cited at-risk factors that contribute to poor mental health among women.[16] According to WHO, given the high incidence of sexual violence they suffer, women are also disproportionately affected by Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).[17]

While one in ten people have a mental health condition, access to services is scarce. About 80 percent of people with disabilities live in middle or low-income countries where it is often challenging to access healthcare, particularly mental health care.[18] Between 76 and 85 percent of people with mental health conditions who live in middle or low-income countries do not have access to mental health services.[19]

Governments have long neglected to invest in mental health services. On average, countries spend less than 2 percent of their health budgets on mental health.[20] In low-income countries, government mental health spending decreases to less than 1 percent of health budgets with less than US $0.25 spent annually per person on mental health, compared to $80 in high income countries.[21] Most concerning is that in low- and middle-income countries, 80 percent of government spending on mental health goes to psychiatric hospitals and not community-based services.[22] The emphasis on tertiary facilities means that people are compelled to travel further and to a psychiatric hospital, a location that is more stigmatizing, which studies have shown are often deterrents in seeking support.[23] Consequently, instead of walking a short distance to a primary health center, families may have to give up a day’s work to travel to reach a psychiatric hospital.[24]

Globally, there is a severe shortage of trained mental health professionals, but the shortfall is particularly acute in low-income countries. The rate of mental health workers in low-income countries is fewer than 2 per 100,000 people, compared with over 70 in high-income countries.[25] In Africa, on average, there is fewer than one mental health worker per 100,000 people, compared with 2.5 in South-East Asia and 50 in Europe.[26] When it comes to psychiatrists, the rate is even lower with low-income countries averaging at 0.1 psychiatrists and lower middle-income countries at 0.5 psychiatrists per 100,000 people.[27] For example, there are 0.19 psychiatrists per 100,000 people in Kenya and 0.12

in Bangladesh.[28]

As of 2018, fewer than half of the 139 countries that have mental health policies had aligned them with international human rights conventions.[29] Human Rights Watch research in over 25 countries around the world has found that people with mental health conditions can face a range of abuses including arbitrary detention, involuntary treatment, including electroconvulsive therapy, forced seclusion as well as physical and sexual violence in psychiatric hospitals.

The cost of mental health services can also be prohibitive. As of 2018, more than two-thirds of all countries did not cover reimbursement for mental health services in national health insurance schemes.[30] Even when mental health services are free or subsidized, in many countries the distance and transport costs are a significant barrier.[31]

In addition, even when there are services, they are often under-utilized or do not comply with human rights standards because of limited understanding and awareness of mental health. In many of the countries where Human Rights Watch conducted research for this report, there is a widespread belief that mental health conditions are the result of possession by evil spirits or the devil, or the consequence of some form of sin, displaying immoral behavior, or—for those whose families are adherents of certain religions—having a lack of faith. Therefore, people first consult faith or traditional healers and often only seek medical advice as a last resort.

Even when people seek mental health services, the quality of care in many countries is substandard. The WHO’s World Mental Health Survey found that only 1 in 5 people with depression receive “minimally adequate” mental health services in high-income countries and it falls to 1 in 27 in low and middle-income countries.[32]

The cost of neglecting mental health is significant; the global economy loses roughly $2.5 to $8.5 trillion per year as a result of reduced economic productivity.[33] The WHO has found that spending $1 on mental health services can yield a return of $4 in the form of improved productivity and health.[34]

Irrespective of age, gender, ethnicity, socio-economic status or cultural background, health and particularly mental health is one of the most basic and necessary assets for human beings.[35] Mental health is not just a human right but a public good that is key to achieving the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDG).[36] Achieving “good health and well-being” is one of the SDGs that enables men, women, and children to go to school, work, and participate in their communities.[37] Despite this, less than 1 percent of international development assistance for health is allocated toward mental health.[38]

Stigma and Its Consequences

None of my relatives want anything to do with me. They run away whenever they see me. They don’t want to socialize with me because my mental health condition brings shame on them. Two months ago, social protection officials tried to discharge me from the hospital and send me to my sister’s house, but she refused. Since then I’ve been living on the streets.

—Carlos, 51, Maputo, Mozambique, November 2019[39]

It’s heart-breaking that two of my cousins who have mental health conditions have been locked away together in a room for many years. My aunt has tried her best to support them but she struggles with stigma and the lack of robust mental health services in Oman. It’s time for governments to step up so that families aren’t left to cope on their own.

—Ridha, family member with relatives shackled in Oman, September 2020[40]

People with psychosocial disabilities face pervasive stigma and bias and are among the most marginalized, enduring stigma and discrimination in every sphere of life—personal, professional and public.[41]

While data disaggregated by disability is hard to come by, available evidence shows that people with psychosocial disabilities often grow up in the confines of their home or an institution, excluded from community life, rarely attending school, getting married and having children, seeking employment, or participating in society.[42] Families can find it challenging to take relatives with psychosocial disabilities out for events or social occasions due to societal stigma and fear the person might say or do something to cause embarrassment.[43] Despite modest governmental efforts to raise awareness in some countries, mental health conditions remain taboo and highly misunderstood. “I’m never invited to happy occasions, weddings or birthdays with my family. I’m only invited to spiritual events because my family thinks I have a spiritual problem, not a mental health condition,” said Carlos, a 51-year-old man from Maputo, Mozambique.[44]

Human Rights Watch research, media reports, and studies show that in many parts of the world a lack of understanding of disability and mental health can cause many people to believe that psychosocial disabilities have a spiritual origin.[45] In urban as well as rural areas in numerous countries there is a widespread belief that mental health conditions are the result of a variety of factors, including witchcraft, black magic, a curse, past sins, or possession by evil spirits or the devil.[46]

For example, many people in countries such as Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Burkina Faso, Egypt, Ethiopia, Ghana, Guatemala, India, Indonesia, Iraq, Kenya, Mexico, Morocco, Mozambique, Nigeria, Oman, Pakistan, Palestine, Peru, Philippines, Saudi Arabia, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Somalia, including in Somaliland, Sudan, and Yemen believe that psychosocial disabilities are the result of possession by evil spirits or witchcraft.[47] In a number of countries including the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ghana, Kenya, and Liberia, children with disabilities can face accusations of witchcraft.[48] In March 2019, six people with mental health conditions, including three children, were chained to logs in a Christian faith healing center in Montserrado, Liberia because they were accused of witchcraft.[49]

A volunteer from an organization providing services to people with disabilities in Cameroon said: “People in Cameroon have negative perceptions about disability. Many think disability is a curse resulting from evil spirits. Others think persons with disabilities are useless. Due to these perceptions, people don’t want to help or mingle with persons with disabilities.”[50]

Ying, a young woman from Goungdong province, in southern China, said: “All through my childhood, my aunt was locked in a wooden shed and I was forbidden to have contact with her. My family believed her mental health condition would stigmatize the whole family. I really wanted to help my aunty but couldn’t. It was heart-breaking.”[51]

The stigma attached to psychosocial disabilities extends to the mental health profession, which often discourages doctors from specializing in psychiatry and causes many general physicians and other health care workers to resist mental health training.[52] This, in part, contributes to the acute shortage of mental health professionals.

In some cases, the physical location of a mental health facility or residential care institution, next to a prison or tuberculosis sanitarium, can aggravate the stigma for mental health professionals as these locations are often perceived as being “undesirable.”[53]

These beliefs often lead people with psychosocial disabilities and their families to first consult faith or traditional healers and only seek medical advice or psychosocial support, such as counseling, as a last resort.

One mother in Bali, Indonesia shared why she chained her son with a mental health condition for over 10 years:

We took Ngurah to more than 40 traditional healers where they poked him with a stick and put herbs in his eyes but it didn’t work. We didn’t know what to do. When Ngurah kept getting lost, the local police and community blamed and put pressure on us. We felt ashamed so we decided to chain him.[54]

Shackling

Definition and Causes of Shackling

Due to prevalent stigma and inadequate support services, families often struggle to cope with the demands of caring for a relative with a psychosocial disability and feel they have no choice but to shackle them.[55] Shackling is also used in church-affiliated prayer camps, traditional or religious healing centers as well as in state-run or private social care institutions as a form of restraint, punishment, or “treatment.”[56]

Shackling is a rudimentary form of physical restraint used to confine people with real or perceived psychosocial disabilities. It is mostly practiced in non-medical settings, by families, a faith healer, or non-medical staff, often in the absence of support or mental health services.

It consists of restraining people:

- Using metallic chains, iron manacles or spreader rods, metal leg or hand cuffs, or wooden stocks;

- Tying or binding them with rope or makeshift cloth; or

- Locking them in a confined space such as a room outside or within a house, shed, hut, cage, or animal shelter (including chicken coops, pig pens, or goat sheds).

People with real or perceived psychosocial disabilities can be shackled for periods ranging from days and weeks, to months, and even years. Shackling is also used as a temporary measure to restrain a person for short periods while the family goes out to work or when the person is having a crisis.

Shackling is typically practiced by families, faith healers, or staff in institutions who believe that the person with the psychosocial disability is possessed or are worried that they may run away or might hurt themselves or others. Some families also use shackling as a way to prevent or control a certain behavior they find disruptive.

Shackling is practiced across socio-economic classes. Even educated and well to-d0 families can resort to shackling. For example, in Bali, Indonesia, a mother from a wealthy family said: “We are from a high caste and when my son gets lost and wanders on the streets without proper clothing, without showering, it’s a cause for shame. It made me sad [to chain him]. No mother on earth wants to chain her son.”[57]

Human Rights Watch has also found evidence of shackling or chaining in psychiatric hospitals in some countries. For example, in 2015 chaining was widespread in psychiatric as well as in mental health wards of general hospitals in Somaliland.[58] Human Rights Watch witnessed several people being shackled in a psychiatric hospital in northern Nigeria. A doctor working at a psychiatric hospital in southern Nigeria said: “We have to use chains in some cases.”[59] In eastern Indonesia, Human Rights Watch witnessed a woman being tied around the waist with a twisted cloth and restrained to her

hospital bed.[60]

Scale

Despite being practiced around the world, shackling remains a largely invisible problem as it occurs behind closed doors, often shrouded in secrecy, and concealed even from neighbors due to shame and stigma.

As a result, documenting shackling cases is extremely challenging. There are no statistics on the scale of shackling at a global level. Very few governments collect data on this practice at a country-level as it often occurs in remote areas, and families are reluctant to speak about shackled relatives. Moreover, the numbers are likely to fluctuate. Even people who are released from chains or confined spaces often go back to being shackled as there is little access to support or mental health services, and stigma and bias persists.

Shackling is common not just in homes but also in state-run or private institutions, including faith healing centers. In many countries there is very limited, if any, government oversight of these institutions. Although faith healing centers can be registered with a government department or religious authority, they are not always regulated or monitored. As a result, many governments do not have any data on the number of private institutions in their country, much less the number of people who are detained or shackled in them.[61]

In the absence of comprehensive global data, it is difficult to precisely determine the magnitude of this practice. However, Human Rights Watch estimates that globally hundreds of thousands of people with mental health conditions have been shackled—chained or locked in confined spaces—at least once in their lives.[62]

Human Rights Watch has found evidence of shackling across60 countries across Asia, Africa, Europe, the Middle East, and the Americas.[63]

In China, a six-part series by the government-controlled Global Times and Beijing News reported that people with mental health conditions were shackled or locked in cages across the country with approximately 100,000 “cage people” in the northern Hebei province alone, near Beijing.[64] In one case, an 8-year-old girl was tied to a tree by her grandparents for nearly six years in Henan province, in central China.[65]

In Indonesia, according to government data, 57,000 people with mental health conditions have been in pasung (shackled) at least once in their lives with approximately 15,000 still living in chains as of November 2019.[66]

In India, in January 2019, the media reported that thousands of people with mental health conditions were chained “like cattle, their feet tied with iron chains and padlocked for days, months and years,” in the state of Uttar Pradesh.[67]

In countries where people believe mental health is a spiritual issue and robust mental health services are lacking, private institutions and faith-healing facilities flourish. For example, Ghana has several hundred prayer camps, but precise numbers are difficult to come by since they are not state-regulated.[68] In the Greater Accra Region, there are an estimated 70 prayer camps.[69] In 2019, large prayer camps such as Mount Horeb detained dozens of people in chains. In Nigeria, Human Rights Watch visited 28 facilities in 8 states and the Federal Capital Territory between 2018 and 2019, across which a few hundred people were arbitrarily detained, and where people were regularly chained or shackled.[70] Across these 28 facilities, the youngest child chained was a 10-year-old boy and the oldest person who was chained was an 86-year-old man.[71]

In Guatemala, Disability Rights International in a 2018 report found hundreds of children with psychosocial or intellectual disabilities tied to furniture or locked in cages in orphanages and institutions.[72] In Morocco, the government in 2015 released over 700 people chained in one shrine alone, about 50 kilometers from Marrakesh in the southwestern part of the country.[73] In Pakistan, the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) reported that in a single Sufi shrine near the city of Burewala in Punjab province hundreds of people with mental health conditions from poor families spent their lives chained to trees.[74] In Togo, prophets can lock up and chain up to 150 people in a single prayer camp.[75]

It is even more complex to account for chaining in small institutions and homes in which people are shackled behind closed doors. People are shackled in locations that are out of sight and out of the way for families: in backyards, outhouses, sheds, or animal shelters. Some institutions are an extension of the faith healer’s house or situated at a secluded end of the compound. For example, Human Rights Watch research in Kenya found about 60 men, women, and children with real or perceived psychosocial disabilities chained, hidden from view, in the compound of the Coptic Church Mamboleo in Kisumu city in western Kenya. In Russia, residents with psychosocial disabilities were being chained by their wrists or ankles to beds, radiators, and other objects in the Trubchevsk Psycho-Neurological Institution near Briansk, located southwest of Moscow. Although mental health professionals had suspected mistreatment at the facility for years, the cases only came to light once video footage was anonymously leaked.[76]

In Mexico, officials from the Office of the Prosecutor for Protection of People with Disabilities told Human Rights Watch: “Families tie them [people with psychosocial disabilities] up regularly. We can tell by the physical signs on their bodies. They have scars.”[77] Esther, 37, a woman with a psychosocial disability who lived with her parents in a rural community in Apodaca, Nuevo León, in northeastern Mexico, was shackled from the time she was a young girl.[78] Despite being shackled for most of her life, her case was never counted or included in government data because it’s a practice that remains invisible and hidden, even from neighbors, the local community, and the authorities. In Yemen, Human Rights Watch documented the case of a woman with a perceived mental health condition who was chained to a door handle so she would not wander outside. In Gaza, where mental health services are scarce, Human Rights Watch found an 18-year-old woman chained by her family on a daily basis since she was 5 years old.[79]

Condition of Confinement

I’ve been chained for five years. The chain is so heavy. It doesn’t feel right; it makes me sad. I stay in a small room with seven men. I’m not allowed to wear clothes, only underwear. I have to go to the toilet in a bucket. I eat porridge in the morning and if I’m lucky, I find bread at night, but not every night…. It’s not how a human being is supposed to be. A human being should be free.

—Paul, man with a psychosocial disability chained in a faith healing institution, Kenya,

February, 2020[80]

Arbitrary Detention

Shackling is a disability-specific form of deprivation of liberty that occurs around the world, regardless of the economic situation of the country or its legal tradition.[81]

Human Rights Watch research across 60 countries found people with real or perceived psychosocial disabilities are arbitrarily detained against their will in homes, state-run or private institutions, as well as traditional or religious healing centers. In none of the hundreds of cases that Human Rights Watch documented were people with psychosocial disabilities allowed or given the opportunity to challenge their detention.

Shackling in the community is a form of home or community-based deprivation of liberty in which the person is entirely in the family’s power with no possibility of challenging the detention. As a result, the person can be shackled for years or even decades. In one case, a man with a psychosocial disability spent 37 years chained in a dark, sweltering cave in the mountains in Wadi Al-Sabab, Saudi Arabia.[82] In another case, a woman with a psychosocial disability was chained for 24 years (since she was 10 years old) in Egypt.[83]

In the case of social care institutions, NGO-run or traditional or religious healing centers, people sometimes used false pretenses to get their relatives to enter an institution, or simply provided no explanation at all. It is typically an administrative process and does not contain any provisions for judicial oversight. Admission forms, where they exist, are signed by family members, the guardian, or staff members. Once the person is committed to an institution, they have no right to appeal or leave until the institution discharges them.

In 2019 at Adwumu Woho Herbal and Spiritual Centre in Senya Beraku, Ghana, about 60 kilometers from the capital, Accra, several men who were shackled and arbitrarily detained shouted out to a Human Rights Watch researcher: “Help us get out of the chains. Help us! Help us! We are suffering. They are abusing our rights over here.”[84]

In the absence of mental health services, people with psychosocial disabilities can also be arbitrarily detained and chained in drug detention centers or prisons. Human Rights Watch research in 2013 in Cambodia found that people with real or perceived psychosocial disabilities are forcibly locked up and often chained in drug detention centers, or in sporadic crackdowns to “clean the streets” ahead of high-profile international meetings or visits by foreign dignitaries.[85] In June 2020, the Ministry of Interior proposed a draft Public Order Law, which will further entrench discrimination against people with psychosocial disabilities as well as against other at-risk groups in society and add to existing deep concerns of the continuing practice of shackling in Cambodia. The bill, in its current draft, provides the authorities with unfettered powers to arbitrarily strip people with mental health conditions of their civil liberties.[86] Article 25, among other problematic provisions, states that a “caregiver or a guardian of a person with a mental disorder shall not allow that person to walk freely in public places.” In a country where people with psychosocial disabilities are stigmatized and subjected to abuse, such broad discretion given to authorities to restrict the freedoms of movement and liberties of a person with mental health conditions will facilitate further abuse and entrenchment of the problem.

In South Sudan, Human Rights Watch in 2012 and Amnesty International in 2016 documented people with real or perceived psychosocial disabilities being chained and detained in prison, not because they had committed a crime but simply because they had a disability.[87] They were unable to appeal their incarceration, and most were imprisoned with no release date. In Juba and Malakal prisons, people with psychosocial disabilities were chained to the floor day and night or tied outside to tree naked, and soiled with their own excrement.[88]

People with mental health conditions can also be arbitrarily detained and chained in state-run social care institutions and psychiatric hospitals. Human Rights Watch research in Nigeria found that people with mental health conditions were held in iron shackles around their ankles in locked-up wards in a psychiatric hospital and in government-run rehabilitation centers.

In Mexico, Felipe Orozco, a 41-year-old man, told Human Rights Watch he had been hospitalized five times because he had a mental health condition. He said that on one occasion in 2018 mental health professionals from the “Dr. Rafael Serrano” psychiatric hospital in Puebla shackled him naked with a padlock during the nights for two-and-a-half weeks, and he was forced to defecate and urinate in his bed. “I was fearful that someone would attack me during the nights, without being able to defend myself because of being shackled.”[89]

People end up living shackled in institutions for long periods because their relatives do not take them home and the institution has nowhere to send them. In the case of private institutions and healing centers, the management may have an incentive to detain people as they are paid by the family. In many countries, it is a profitable business.[90] For example, in Nigeria, in 2019, while the average monthly earning was roughly 18,000 Naira ($47), a traditional healer would charge anywhere between 2,000 to 150,000 Naira ($5 to $388) for spiritual treatment.[91]

While there are formal procedures governing admission in social care institutions, the healing centers Human Rights Watch visited in a number of countries had no formal admission or discharge processes. In traditional or religious healing centers, there is no medical diagnosis and the basis for admission and discharge is left entirely to the discretion of the faith or religious healer.

If the family does not come to pick up the relative or abandons them at the institution, the person can end up spending many years or even the rest of their life shackled in the social care institution or healing center. In some cases, families left fake phone numbers and addresses in order to abandon the relative, while in other cases they simply moved homes or failed to show up.

International human rights law guarantees to persons with disabilities the right to liberty on an equal basis with others. Deprivation of liberty is permissible only when it is lawful and not arbitrary, and includes initial and periodic judicial review.[92] It cannot be discriminatory and should never be justified on the basis of the existence of a disability.[93]

Overcrowding, Poor Sanitation and Lack of Hygiene

I go to the toilet in nylon bags, until they take it away at night. I last took a bath days ago. I eat here once a day. I am not free to walk about. At night I sleep inside the house. I stay in a different place from the men. I hate the shackles. I want to move about, I have asked the baba [faith healer] to take them off, but he won’t.

—Mudinat, a woman with a psychosocial disability chained at a church, Abeokuta, Nigeria, September 2019[94]

While the conditions of confinement may vary based on the method of shackling, location, and country, one thing remains the same: people who are shackled are forced to live in extremely unsanitary and degrading conditions.

Human Rights Watch research found that in institutions and healing centers visited, people with psychosocial disabilities often live in severely overcrowded and unhygienic conditions. This is in part due to a lack of government support and monitoring.

In Indonesia, Human Rights Watch found approximately 90 women living in a room that could reasonably accommodate no more than 30, in Panti Laras 2, a state-run institution in Cipayung, on the outskirts of Jakarta.[95] Staff members hesitated to let Human Rights Watch enter the room asking: “How will you enter? There is no space.”[96] To walk in, one had to physically tiptoe over hands and feet. Exacerbated by such close and unsanitary living conditions, lice and scabies are a major problem in many institutions.[97]

Personal hygiene is a serious problem since people who are chained often do not have access to a toilet. As a result, they urinate, defecate, eat, and sleep in a radius of no more than one to two meters. In some instances, people are provided with a small bucket to urinate and defecate in, but these are emptied only once a day leaving a putrid smell in the room for most of the day. In other cases, people have to use a drain or an open toilet in the room. Even in institutions where suitable toilets exist, residents do not always have access to them or they are inadequate. In some healing centers, people were allowed to bathe once a day using a hose in their rooms. And women and girls are not supported to manage their menstrual hygiene, for example through the provision of sanitary pads.

Families or staff in institutions often make the person who is shackled stay naked, dress in very scant clothing, or wear an adult diaper, so it is easier for them to keep the person clean and they do not have to regularly wash soiled clothing.

Aisha, mother who chains her 18-year-old daughter with a psychosocial disability in the Gaza Strip told Human Rights Watch:

We keep her chained from morning until evening, after al-Maghreb prayer. She uses diapers 24 hours a day, she can’t use the toilet. She doesn’t wear regular clothes…. We have to chain her, otherwise she will take off her clothes and diapers... and play with her own poop. She could flee outside the house. We don’t give her a chance to flee. We are monitoring her.[98]

Archbishop Danokech of the Holy Ghost Coptic Church of Africa in Kisumu, western Kenya, where over 60 men, women, and children with psychosocial disabilities are detained and most of whom are chained, told Human Rights Watch: “We do not want them to wear clothes. We keep them in their underclothes. We remove their clothes so they won’t run away or escape.”[99] Another supposed reason for keeping the residents naked was to prevent them from attempting to take their own lives by hanging, although staff still gave residents blankets and mosquito nets.

Incarceration, Restrictions on Movement

I feel sad, locked in this cell. I want to look around outside, go to work, plant rice in the paddy fields. Please open the door. Please open the door. Don’t put a lock on it.

—Made, a man with a psychosocial disability locked in a purpose-built cell on his father’s land for two years, Bali, Indonesia, November 2019[100]

The nature of shackling means that people live in very restrictive conditions that reduce their ability to stand or move at all. At the Edumfa Heavenly Ministry Prayer Camp in Cape Coast, Ghana, people with real or perceived psychosocial disabilities are confined in cages and are rarely allowed out of such cages.[101] Most cages are so narrow that the men cannot even stretch out their arms.

In Mexico, for example, Disability Rights International documented children with psychosocial disabilities in cages or tied down with bandages.[102] When children are shackled, they are deprived of playing, making friends, going to school, growing up in a family, and having a normal childhood. In some cases, the children were fully wrapped in bandages, duct tape or clothing, like mummies. In one case, a person died while tied up and locked in one of the bathrooms, which was used as an isolation room.[103]

In some cases, people are shackled to each other, forcing them to go to the toilet, bathe, eat, or sleep together. Human Rights Watch research in 2019 at an NGO-run marastoon (institution) in Herat, Afghanistan, found dozens of men with psychosocial disabilities chained in pairs to other’s ankles.[104] In a privately-run social care institution near Briansk, southwest of Moscow, Russia, staff regularly brought people with psychosocial disabilities to the dining hall chained to each other, and forced them to eat in handcuffs.[105]

Shackling affects a person’s mental as well as physical health. A person who is shackled can be affected by post-traumatic stress, malnutrition, infections, nerve damage, muscular atrophy, and cardio-vascular problems.[106]

In situation of conflict or crises, and more recently during the Covid-19 pandemic, people who are shackled are at greater risk because they are unable to leave or flee. For example, in Yemen, Amnesty International documented cases of people with psychosocial disabilities who were unable to flee from violence because they were chained.[107] When the city of Taizz, Yemen, was attacked in mid-2017, Jalila al-Saleh Ali fled with her two sons, and in her distress left behind her husband with a psychosocial disability in chains. “It was like my mind had gone blank on account of the fright,” she said. “I forgot him. When the fighting happened, we left him next to the house tied up. We don’t know if he’s dead or alive.”[108] While Covid-19 has exposed the importance of psychological wellbeing and the need for connection and support within communities, it has exacerbated the risk to people with psychosocial disabilities. Covid-19 is an extreme threat to people with psychosocial disabilities who are shackled in homes or overcrowded institutions without proper access to sanitation, running water, soap, or even basic health care. In many countries, Covid-19 has disrupted mental health services, which can put people with psychosocial disabilities at risk of being shackled. This is the case for Sodikin, a 34-year-old man with a psychosocial disability, who had been released from chains after over 8 years shackled in a shed outside his family home in Cianjur, West Java in Indonesia.[109] When his community went into lockdown and Sodikin lost access to community-based mental health services, his family was unable to support him and locked him in a room.

Lack of Shelter and Denial of Food

Shelter is a major concern for people shackled outdoors at home, in prayer camps, or in open-air institutions. Human Rights Watch interviewed people with psychosocial disabilities who were shackled to trees, logs, pillars in a courtyard, dilapidated sheds without a roof over their heads, protection from the sun or rain, and with constant exposure to mosquitoes and pests.

Many spiritual healing centers that Human Rights Watch visited were located in open fields or forests; some operated out of structures that were half-built and offered only a rooftop for shelter. Many had old and leaking roofing. Individuals were either crowded in the few spots where there was shade or baked in the sun. In some instances, people or their families had fashioned bamboo beds and grass-thatched shelters under a tree to get protection from the sun, but many slept on cold, hard concrete floors with no mattress or bedding.

People shackled in homes typically ate the same meal as the family. However, in prayer camps and institutions, many interviewees spoke of persistent, gnawing hunger from forced fasting or inadequate food. In prayer camps in Ghana, administrators and pastors told Human Rights Watch that fasting was a key component of “curing” a psychosocial disability.[110] Fasting would help to starve evil spirits and enable God and prayer to heal them.[111] People interviewed said there was too little food, sometimes only one meal a day. Some individuals in Hebron Prayer Camp, north of Accra, Ghana were denied food for up to seven days.[112]

When institutions provided food, people with psychosocial disabilities told Human Rights Watch that it was too meager—at times, just one meal a day. Faith healers in Ghana, Indonesia, Kenya, and Nigeria reported sharing the little food available among all the residents, especially because some families did not provide food for their relatives, and prayer camps and institutions said they did not have the resources to buy enough food for everyone. While the expectation was that families would regularly bring food for relatives, this rarely happened. Many interviewees appeared undernourished and complained of hunger. In many institutions in Indonesia, people with psychosocial disabilities were fed meals devoid of proper nutrition such as instant noodles for most meals.[113]

Involuntary Treatment

People in the neighborhood say that I’m mad [maluca or n’lhanyi]. I was taken to a traditional healing center where they cut my wrists to introduce medicine and another one where a witch doctor made me take baths with chicken blood.

—Fiera, 42, woman with a psychosocial disability, Maputo, Mozambique, November 2019[114]

I was chained, beaten, and given devil incense. They feel you’re possessed and put liquid down your nose to drive out the devil.

—Benjamin, 40, mental health advocate who was chained at a church in Monteserrado, Liberia, February 2020[115]

People with psychosocial disabilities, including children, who are shackled in homes or institutions are routinely forced to take medication or subjected to alternative “treatments” such as concoctions of “magical” herbs, fasting, vigorous massages by traditional healers, Quranic recitation in the person’s ear, singing Gospel hymns, and special baths.

Carlos, a man with a psychosocial disability who has been chained and treated against his will in faith healing institutions in Mozambique, told Human Rights Watch:

I’ve been tied many times and given bitter medicines through the nose…. They give you roots, leaves as medicine. Their treatment was always unsuccessful. My mother and father would come and take shifts. One time I escaped with the rope tied to a log. They caught me and I pleaded with my mother to bring me home, I really suffered in that place. [116]

In healing centers, individuals with psychosocial disabilities are forced to partake in all sorts of rituals, including taking baths with special water or chicken blood, and undergo “therapeutic” massages as part of their treatment.[117]

Staff in state-run and private institutions admitted that they hold people down to put pills in their mouth or force-feed them food or drinks laced with medicines. In one institution, near Briansk, Russia, residents who were “unruly,” would be chained, forcibly sedated.[118]

The right to health care, particularly mental health care, on the basis of free and informed consent of the person with a real or perceived psychosocial disability is routinely ignored.

Informed consent is a bedrock principle of medical ethics and international human rights law, and forcing individuals to take medicines without their knowledge or consent violates their rights.[119] The United Nations special rapporteur on torture has noted that “involuntary treatment and other psychiatric interventions in health-care facilities” can be forms of torture and ill-treatment.[120] In addition, the UN special rapporteur on violence against women has condemned forced psychiatric treatment as a form of violence.[121]

In situations in which a person cannot give consent to admission or treatment at that moment, and their health is in such a state that if treatment is not given immediately, their life is exposed to imminent danger, immediate medical attention may be given in the same manner it would be given to any other person with a life-threatening condition who is unable to consent to treatment at that moment.[122] However, Human Rights Watch research found that people with psychosocial disabilities were forcibly treated, even in non-life threatening situations.

Physical and Sexual Violence

They always beat me up, at times they assigned my own children to beat me up, for instance this one who takes care of my drugs bill.

—Halima, woman with a psychosocial disability, Kano, Nigeria, September 2019[123]

People with psychosocial disabilities who are shackled in homes and institutions experience physical abuse if they try to run away from institutions or don’t obey the staff. James, a man with a psychosocial disability who has been chained for several years in a Christian healing institution in Kenya, said: “They cane us if we make a mistake. If we miss hygiene, they give us a punishment. If you get exhausted due to a lot of work, and so don’t want to work anymore, you get caned.”[124] In Nigeria, people in Islamic rehabilitation centers told Human Rights Watch that staff whipped them. In one center in northern Nigeria, Human Rights Watch found a dozen people who showed researchers scars on their arms, chests, and backs that they said were from floggings by staff.

Amina, who had a breakdown after her mother died and was taken to various Islamic healers, said she was tied with ropes, beaten, and spat on in one rehabilitation center in Kaduna, and then molested by a traditional healer in Abuja who came to her home: “He told me to undress, that it is the part of the healing process, and then he started touching my body,” Amina said. “Explain to me, how is that part of a healing process? How is that Islamic?”[125]

In institutions visited by Human Rights Watch in Indonesia, male staff would enter and exit women’s wards or sections at will or were responsible for the women’s section, including at night, which put women and girls at increased risk of sexual violence, as well as subjected them to a constant sense of insecurity and fear. In Nigeria, boys as young as 10 were chained together in rooms with adult men, leaving them at risk of abuse.[126] In healing centers in countries such as Nigeria and Indonesia, men and women are chained next to each other, leaving women no option to run away if they encounter abuse.[127]

Those who experience sexual violence encounter many barriers to reporting the abuse safely and confidentially, and are unlikely to access time-sensitive health care, for example to prevent sexually transmitted infections or pregnancy or to access

support services.

Global Efforts to End Shackling

The chaining of people with mental health conditions needs to stop – it needs to stop.

— Honorable Tina Mensah, Ghana’s deputy health minister, Accra, Ghana, November 8, 2019[128]

While many countries are increasingly starting to pay attention to the issue of mental health, the practice of shackling remains largely invisible. There are currently no coordinated international or regional efforts to eradicate shackling. Although it is noteworthy that some governments have put in place measures to tackle the practice of shackling, their laws and policies are not always effectively implemented, and on-the-ground monitoring remains weak overall.

Countries with Laws and Policies Against Shackling

Of the 60 countries where Human Rights Watch found evidence of shackling, only a handful of countries have laws, policies, or strategies in place that explicitly ban or aim to end shackling of people with mental health conditions.

For example, in 2017 India passed a landmark mental health care bill that explicitly prohibited people with mental health conditions from being “chained in any manner or form whatsoever.”[129] While the provision has proven challenging to implement, it enabled a lawyer to challenge in court cases of people shackled in homes and faith-based institutions in the state of Uttar Pradesh, India.[130] In 2019, the Supreme Court of India directed the government to take immediate action, stating that keeping people with mental health conditions “handcuffed or chained is in violation of their human rights.”[131] In 2017, Dr. Akwasi Osei, CEO of the Mental Health Authority in Ghana, announced the government would enforce the 2012 Mental Health Act provision that people with psychosocial disabilities “shall not be subjected to torture, cruelty, forced labor and any other inhuman treatment,” including shackling.[132]

However, even in countries that have formally banned shackling, the practice continues to exist due to prevalent stigma and inadequate support services.

Anti-Shackling Initiatives

In a few countries, government efforts at the national level to eradicate shackling have had some success in creating a roadmap to ending the practice.

In 2006, the WHO launched the “Chain-Free Initiative” in Somalia and Afghanistan. The objective was to combat stigma by raising awareness on mental health and put an end to chaining in homes as well as in hospitals. As a result of this initiative, according to the WHO, 1,700 people were freed from chains in Somalia between 2007 and 2010.[133] Of these, 1,355 had been chained in Habeb hospital in Mogadishu, the capital, and 417 in the surrounding community. Overt commitment by political leaders and building capacity of existing health workers were critical to the success of the chain-free initiative

in Somalia.[134]

Between 2005 and 2015, China implemented the “686” pilot program to provide basic mental health services on a large scale, which included an initiative to “unlock” people with psychosocial disabilities shackled in homes.[135] By 2012, the program had “unlocked” 271 people who had been shackled for periods ranging from 2 weeks to 28 years across 26 provinces.[136] The program demonstrated that accessible community-based mental health services were key to ensuring people remained free from chains and proved to be an example of how non-healthcare workers could be mobilized to deliver services in rural and low-resource settings. However, one of the main concerns about the 686 program was that it predominantly took a medical approach to mental health that focused on freeing people from chains and then admitting them to a psychiatric hospital for treatment or putting them on a regimen of mental health medication.

Under the 686 “unlocking” initiative, 266 people were given mental health medication and 88 percent of all those who were unlocked were admitted to a psychiatric hospital. Human Rights Watch’s research into mental health settings in at least 25 countries has found that people with mental health conditions can face a range of abuses when sent to a psychiatric hospital, such as arbitrary detention, involuntary treatment, including electroconvulsive therapy, forced seclusion as well as physical and sexual violence. As of 2012, 92 percent of the people who had been “unlocked” in China remained free from chains.[137] There is no publicly available current data on whether the people released by the 686 initiative remain free or whether they have access to ongoing support in the community.

In Sierra Leone, while chaining continues to be practiced in faith healing centers, it is now prohibited at the Sierra Leone Psychiatric Teaching Hospital, the country’s only mental health facility located in Freetown.[138] Until 2018, people with mental health conditions being admitted to the psychiatric hospital were asked to pay for a padlock and chain prior to admission.[139] After long-term advocacy by organizations such as the Mental Health Coalition of Sierra Leone, chaining was banned in policy. In June 2020, President Maada Bio of Sierra Leone inaugurated the renovated and chain-free Sierra Leone Psychiatric Teaching Hospital.[140]

Indonesia’s Efforts to End ShacklingThe Indonesian government officially banned pasung (shackling) by law in 1977. While the government has taken important steps to end shackling, the practice remains to this day. According to Indonesia’s 2018 Basic Health Survey (Riskesdas), 14 percent of people with “serious” mental health conditions have been shackled at least once in their lives and about 30 percent of them have been shackled within three months of the survey.[141] Phase 1 In 2010, Indonesia’s health ministry launched the “Indonesia Free from Pasung,” a program that aimed to eradicate the practice by 2014. The deadline was extended to 2019. It focuses on raising awareness about mental health and pasung, integrating mental health into primary health services, providing mental health medication at the 9,909 community health centers, training health staff to identify and diagnose basic mental health conditions, and creating community mental health teams called Tim Penggerak Kesehatan Jiwa Masyarakat (TPKJM) that act as a coordination mechanism between the department of health and others departments at the provincial and district levels to monitor and facilitate the release of people from pasung. However, implementation has depended on the provincial governors issuing a decree and deploying adequate resources. To date, about 20 out of Indonesia’s 34 provinces—including Central Java, West Nusa Tenggara, East Java, Jambi, Yogyakarta, and Aceh—have a functional pasung-free initiative. Additionally, the Social Affairs Ministry has 12 “rapid response” teams attached to 20 state-run institutions (pantis) across the country that conduct community outreach activities including rescuing people from pasung when they come across them. Due to a lack of resources, coordination, and training, both the TPKJM and the “rapid response” teams struggle to successfully rescue people from pasung. Even those who are rescued, return to pasung once they return to the community due to a lack of follow-up and access to community-based support and mental health care services, and continued stigma in the community. Phase 2 In January 2017, the Indonesian Health Ministry rolled out Program Indonesia Sehat dengan Pendekatan Keluarga (Healthy Indonesia Program with Family Approach), a community outreach program in which health workers use a “family-based approach,” going house to house to collect data, raise awareness, and provide services relating to 12 measures of family health, including mental health. The program is an ambitious government initiative that seeks to ensure that even the most rural, isolated, and reluctant communities get access to health services. The program’s home visits are critically important because they eliminate the need for family members to take time off from work and spend money to travel to health centers. The program’s innovative “family-based approach” examines 12 measures that together reveal family health: access to clean water, hypertension, tuberculosis, smoking, family planning, access to government health insurance, maternal health, child nutrition, immunization, breast feeding, sanitation, and mental health. If a family fairs poorly on even one indicator, then it is identified as needing assistance. This system effectively gives mental health the same importance as all other indicators and ensures that community health workers provide immediate and ongoing mental health services to meet their target of 100 percent coverage. For the program’s nationwide rollout, the Health Ministry trained 25,000 master trainers to train three to five staff members in every community health center across Indonesia. Relying on community workers such as midwives or social workers to deliver basic mental health services has meant that the shortage of trained mental health professionals is no longer a barrier. The trained staff in turn educate additional health center staff about the program and mental health. The government’s target was to ensure full coverage of over 65 million households in Indonesia through all 9,909 community health centers by the end of 2019. Since the program involves home visits, it becomes easier for community health workers to detect cases of shackling and facilitate the release of shackled people. During house visits, the community health worker collects data, educates the family about mental health, provides counseling, and helps them get a national health insurance card for free or subsidized health services. In addition, the person with a psychosocial disability and their family can visit the community health center for one-on-one counseling with a doctor or nurse, they can get medication, and they can participate in occupational therapy or other activities. In some cases, the health center facilitates formation of peer support groups through the messaging application WhatsApp, links people to training on how to start a small business, and helps them get funding to start the business. As of September 2020, the program had reached 48 million – roughly 70 percent – of Indonesian households. The data collected indicates, however, that only about 25 percent of people with psychosocial disabilities surveyed have access to mental health services. |

WHO’s Quality Rights Initiative: An Example of Good PracticeThe WHO’s QualityRights initiative, introduced in 31 countries around the world, is a groundbreaking effort to improve access to quality mental health and social services for people with disabilities and seeks to transform health systems and services towards a person-centered and human rights-based approach, in line with the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD).[142] At the core of this initiative is respect for the rights of people with psychosocial or intellectual disabilities, including the right to live independently in the community. QualityRights also focuses on empowering advocates and self-advocates to influence policy-making and push for national legal reforms to meet the standard set by the CRPD. As part of the project, WHO developed a toolkit with practical information and resources for countries to assess and improve the quality of and human rights standards in mental health services. These include e-trainings and guidance materials for mental health professionals, people with psychosocial disabilities and their families, and NGOs. Both the governments of Ghana and Kenya have recently launched the QualityRights initiative on a country-wide scale. Since the launch of QualityRights in Ghana in February 2019, around 15,000 people have enrolled in the course and around 7,430 people have completed the training. In Kenya, which launched in November 2019, almost 3,260 people have enrolled and around 732 have completed the training. A 2019 evaluation conducted by the Institute of Mental Health, University of Nottingham found that people who completed the QualityRights e-training course showed significant improvements in attitudes and practices towards a human rights based approach to mental health, including the need to end force and coercion in mental health services and to provide information and choice as well as respect people’s decisions concerning treatment. |