President Jair Bolsonaro tried to sabotage public health measures aimed at curbing the spread of Covid-19, but the Supreme Court, Congress, and governors upheld policies to protect Brazilians from the disease.

Bolsonaro’s administration has weakened environmental law enforcement, effectively giving a green light to criminal networks that engage in illegal deforestation in the Amazon and use intimidation and violence against forest defenders.

President Bolsonaro accused Indigenous people and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), without any proof, of being responsible for the destruction of the rainforest. He also harassed journalists.

In 2019, police killed 6,357 people, one of the highest rates of police killings in the world. Almost 80 percent of victims were Black. Police killings rose 6 percent in the first half of 2020.

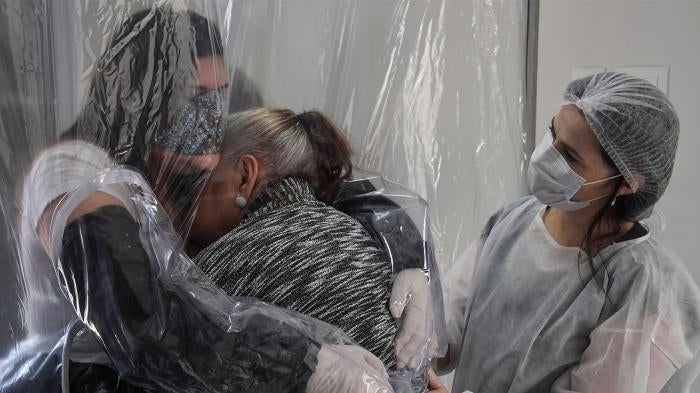

Covid-19

President Bolsonaro downplayed Covid-19, which he called “a little flu;” refused to take measures to protect himself and the people around him; disseminated misleading information; and tried to block states from imposing social distancing rules. His administration attempted to withhold Covid-19 data from the public. He fired his health minister for defending World Health Organization recommendations, and the replacement health minister quit in opposition to the president’s advocacy of an unproven drug to treat Covid-19.

Brazil had 5.4 million confirmed Covid-19 cases and 158,969 deaths as of October 29. Black Brazilians were more likely than other racial groups to report experiencing symptoms consistent with Covid-19, and more likely to die in the hospital. Among other factors, experts attributed the disparity to higher rates of informal employment among Black people, preventing many from working from home, and to higher prevalence of pre-existing conditions.

Poor access to health care and prevalence of respiratory or other chronic diseases made Indigenous people particularly vulnerable to complications from Covid-19. The Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil, an NGO, had registered 38,124 cases and 866 deaths of Indigenous people in Brazil as of October 29.

In June, Congress passed a bill forcing the government to provide emergency healthcare and other assistance to help Indigenous people cope with the pandemic. President Bolsonaro partially vetoed it, but Congress overturned the veto. In July, the Supreme Court ordered the Bolsonaro administration to draft a plan to fight the spread of Covid-19 in Indigenous territories.

The cramped quarters, poor ventilation, and inadequate health care prevalent in Brazil’s prisons and juvenile detention centers offered prime conditions for Covid-19 outbreaks.

As of December 2019, more than 755,000 adults were incarcerated, exceeding the maximum capacity of jails and prisons by about 70 percent, according to the Ministry of Justice. Prisons had one general doctor per 900 detainees and one gynecologist per 1,200 incarcerated women.

The Bolsonaro administration failed to address prison overcrowding, but the National Council of Justice (CNJ, in Portuguese), a body that regulates the functioning of the judicial system, asked judges to reduce pretrial detention during the pandemic and consider early release for certain detainees. As of September 16, judges ordered nearly 53,700 people transferred to house arrest in response to Covid-19, according to official data obtained by Human Rights Watch.

In July, President Bolsonaro vetoed legislation requiring the use of masks in prisons and juvenile detention facilities, but the Supreme Court found the veto had violated procedural rules and ordered that the legislation be implemented. The Court also based its decision on the existence of “structural deficiencies” in health services in detention facilities.

About 46,210 detainees and detention facility staff had contracted Covid-19 and 205 had died as of October 26, according to CNJ.

The CNJ also asked judges to consider alternatives to detention for children in conflict with the law during the pandemic. Following that recommendation, the number of children and young adults in detention fell to about 14,600, according to judicial data obtained by Human Rights Watch. Yet, at least 38 juvenile detention facilities exceeded their maximum capacity by up to 90 percent during the pandemic.

In August, Brazil’s Supreme Court ordered judges to end overcrowding in juvenile detention centers by applying alternatives to detention.

People with disabilities confined in institutions are at a greater risk of contracting Covid-19 due to overcrowded and often unhygienic conditions, although lack of centralized data makes it impossible to assess the impact of the virus. In May, the National Secretariat of Social Assistance called on local authorities to consider alternatives to institutionalization and adopt anti-Covid-19 measures in institutions.

Public Security and Police Conduct

In Rio de Janeiro, police killed 744 people from January through May 2020—the highest number for that period since at least 2003—even though crime levels were lower, as Covid-19 social distancing measures reduced the number of people on the streets.

In May, as volunteers outside a school in an impoverished Rio neighborhood handed out food to families left hungry by the economic fallout from Covid-19, police opened fire, killing a 19-year-old student. They said they were responding to gunfire from unidentified suspects. Shootings involving the police had already disrupted food distribution on at least four occasions in a month.

In June, the Supreme Court prohibited police from conducting raids in low-income neighborhoods in Rio de Janeiro during the pandemic, except in “exceptional cases.” As a result, police killings dropped by 72 percent from June through September, compared to the same period in 2019.

In São Paulo, killings by on-duty officers were up 9 percent from January through September.

Nationwide, killings by police rose 6 percent in the first half of 2020, according to official data compiled by the nonprofit Brazilian Forum of Public Security. In 2019, police killed 6,357 people. Almost 80 percent of them were Black.

In August 2020, police launched an operation in Nova Olinda do Norte, in Amazonas state, after drug dealers allegedly shot at a boat fishing without a permit in an environmentally protected area, slightly wounding the state secretary for social development. At least seven people were killed during the operation, including two police officers, and three people were missing as of September 24, the Justice Ministry told Human Rights Watch. Residents reported that police committed extrajudicial executions and other abuses, including torturing a community leader.

While some police killings are in self-defense, many others are the result of excessive use of force. Police abuses contribute to a cycle of violence that undermines public security and endangers the lives of civilians and police officers alike. From January through June 2020, 110 police officers were killed, according to the Brazilian Forum of Public Security.

Homicides rose 7 percent in the first half of 2020, reversing two years of declining rates.

Children’s Rights

Around 150 bills banning discussion of sexual orientation, gender identity, or political views in schools had passed or were pending before Congress and state and municipal legislatures as of September 2020, according to a website maintained by university professors. As of October, the Supreme Court had struck down eight laws against “political indoctrination” or the promotion of “gender ideology,” finding that they violated academic freedom and the right to education.

In September, the education minister said gender should not be discussed in schools and that people “choose to be gay” and they often come from “misfit families.”

A study by the Senate estimated that 18 percent of students in private primary, secondary, and tertiary schools and 40 percent of students in public schools had their classes cancelled due to the pandemic as of July. The rest had to access classes online, but 20 percent of those lacked internet connection at home.

Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity

In May 2020, the Supreme Court revoked a ban enacted by the federal government on men who had sexual relations with other men donating blood.

Between January and June 2020, the national Human Rights Ombudsman’s Office received 1,134 complaints of violence, discrimination, and other abuses against lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) persons.

Women’s and Girls’ Rights

The adoption of the 2001 “Maria da Penha” law was an important step in fighting domestic violence, but implementation has lagged.

In 2019, one million cases of domestic violence and 5,100 cases of femicide—defined under Brazilian law as the killing of women “on account of being persons of the female sex”—were pending before the courts.

Police reports of violence against women dropped significantly amid the Covid-19 pandemic, while calls to a hotline to report violence against women increased 27 percent in March and April 2020 compared to the previous year, suggesting women may have difficulty going to police stations to report violence.

Abortion is legal in Brazil only in cases of rape, to save a woman’s life, or when the fetus has anencephaly, a condition that makes it difficult for the fetus to survive.

In June, the Bolsonaro administration removed two public servants after they signed a technical note recommending that authorities maintain sexual and reproductive health services during the Covid-19 pandemic, including “safe abortion in the cases permitted by Brazilian law.”

In August, the Bolsonaro administration erected new barriers to accessing legal abortion, including by ordering health professionals to report to police rape survivors who sought to terminate pregnancies.

Only 42 hospitals—in a country of 212 million people—were performing legal abortions during the Covid-19 pandemic, the NGO Article 19 and the news websites AzMina and Gênero e Número reported, compared to 76 during 2019. In August, a hospital in Espírito Santo state denied an abortion to a 10-year-old girl who was raped for years, saying it lacked authority to conduct it. After a judge’s intervention, the girl obtained an abortion in another state.

Women and girls who have unsafe and illegal abortions not only risk injury and death but face up to three years in prison, while people convicted of performing illegal abortions face up to four years in prison.

An outbreak of the Zika virus in 2015-2016 caused particular harm to women and girls. When a pregnant woman is infected, Zika can cause complications in fetal development, including of the brain. In April 2020, the Supreme Court rejected on a technicality a petition that sought to legalize abortion for people infected with Zika during pregnancy and to increase state support for families affected by Zika.

In September 2020, Brazil’s football association announced it would pay equal salaries to women and men on the country’s national teams.

In 2018, several Supreme Court rulings and a new law mandated house arrest instead of pretrial detention for pregnant women, mothers of people with disabilities, and mothers of children under 12, except for those accused of violent crimes or crimes against their dependents. Official data show that judges granted house arrest to more than 3,380 women in 2019, but 5,111 women who should have benefited from the new rules awaited trial behind bars, the Ministry of Justice told Human Rights Watch. From January through July 2020, judges granted house arrest to at least an additional 938 women, but the ministry did not provide data on how many were awaiting a decision.

In October 2020, the Supreme Court decided that the rules for house arrest instead of pre-trial detention should apply to fathers who have sole responsibility for children under 12 or for people with disabilities, as well as to any other person who is “indispensable” for the care of children under 6 or people with disabilities.

Freedom of Expression

In March, President Bolsonaro suspended deadlines for government agencies to respond to public information requests during the Covid-19 emergency and prevented citizens from appealing declined requests. The Supreme Court overturned these orders.

Since taking office, President Bolsonaro, political allies, and government officials have lashed out at reporters more than 400 times, according to Article 19. The president threatened to punch one journalist in the face in August 2020. His supporters harassed reporters at demonstrations and outside the presidential palace, which made several outlets suspend coverage in May. The government asked the Federal Police to investigate alleged defamation by two journalists and a cartoonist who criticized the president.

The Justice Ministry prepared confidential reports on almost 600 police officers and three academics it identified as “antifascists.” The Supreme Court ordered the ministry to stop collecting information about people exercising their rights to freedom of expression and association.

Brazil’s Senate passed a “fake news” bill that threatens the right to privacy and free speech. It was pending in the Chamber of Deputies at time of writing.

Disability Rights

Thousands of adults and children with disabilities are needlessly confined in institutions where they may face neglect and abuse, sometimes for life.

In September 2020, the government issued a new national policy that appeared aimed at establishing segregated schools for certain people with disabilities, despite the right of all people with disabilities to an inclusive education.

Migrants, Refugees, and Asylum Seekers

Thousands of Venezuelans, including hundreds of unaccompanied children, have crossed the border into Brazil in recent years, fleeing hunger, lack of basic health care, or persecution. More than 262,000 Venezuelans lived in Brazil as of August 2020.

Brazil’s June 2019 legal recognition of a “serious and widespread violation of human rights” in Venezuela speeds up the granting of asylum to Venezuelans. In August 2020, Brazil’s federal refugee agency extended the policy for another year. From January through August, Brazil granted refugee status to 38,000 Venezuelans.

In March, in response to the Covid-19 pandemic, the federal government banned Venezuelans from entering Brazil through land, later adding other nationalities. By October, most foreign nationals except for permanent residents of Brazil were barred from entering the country through land or water. Permanent residents could return to Brazil unless they entered the country from Venezuela, in which case they were still banned. In addition, the federal government ordered the repatriation or deportation of those who managed to enter, even if they were asylum seekers.

Those measures violate Brazil’s international obligations. Even in times of emergency, governments remain obliged not to return refugees to a threat of persecution, exposure to inhumane or degrading conditions, or threats to life and physical security, and they should not impose restrictions that are discriminatory.

Environment and Indigenous People’s Rights

Criminal networks that are largely driving illegal deforestation in the Amazon continued to threaten and even kill Indigenous people, local residents, and public officials who defended the forest.

From 2015 to 2019, more than 200 people were killed in the context of conflicts over the use of land and resources in the Amazon—many of them by people allegedly involved in illegal deforestation—the non-profit organization Pastoral Land Commission reported. In the vast majority of these cases, the perpetrators have not been brought to justice.

Since taking office in January 2019, the Bolsonaro administration has weakened the enforcement of environmental laws. In April 2020, after a successful anti-illegal mining operation, the administration removed the three top enforcement agents at the country’s main environmental agency.

In October 2019, the environment ministry implemented new procedures establishing that environmental fines do not need to be paid until they are reviewed at a “conciliation hearing.” Environmental agents have issued thousands of fines since then, but the ministry had only held five hearings as of August 2020.

In May 2020, the government transferred responsibility for leading anti-deforestation efforts in the Amazon from environmental agencies to the armed forces, despite their lack of expertise and training.

Deforestation in the Amazon rose by 85 percent in 2019, according to preliminary data. From January through September 2020, deforestation fell 10 percent, but the number of fires reached the highest level in 10 years.

Fires had burned more than a quarter of Pantanal, the largest marshland in the world, as of October 2020, the greatest destruction in more than two decades. Federal Police and prosecutors believe large landowners illegally set fires to clear land for cattle.

Air pollution caused by forest fires takes a major toll on public health. A study by Human Rights Watch, the Institute for Health Policy Studies (IEPS), and the Amazon Environmental Research Institute (IPAM) found that millions of people were exposed to harmful levels of air pollution due to the fires in the Amazon in 2019, resulting in an estimated 2,195 hospitalizations.

President Bolsonaro called NGOs working in the Amazon a “cancer” that he “can’t kill,” and accused them, without any proof, of being responsible for the destruction of the rainforest. He also blamed Indigenous people and small farmers for Amazon fires.

In September 2020, the environment minister petitioned a federal court to order a leading environmental defender to explain comments criticizing the minister, a measure seemingly intended to intimidate the defender. In October, media reported that the Bolsonaro administration had deployed the country’s secret service to spy on the Brazilian delegation, NGOs, and others at the December 2019 UN Climate Change Conference in Madrid.

In 2019, invasions of Indigenous territories to access their resources increased by 135 percent, according to the nonprofit Indigenist Missionary Council.

In February 2020, President Bolsonaro sent a bill to Congress to open Indigenous territories to mining, dams, and other projects with heavy environmental impacts. The bill was still pending at time of writing.

Military-Era Abuses

The perpetrators of human rights abuses during the 1964 to 1985 dictatorship are shielded from justice by a 1979 amnesty law that the Supreme Court upheld in 2010, a decision that the Inter-American Court of Human Rights ruled was in violation of Brazil’s obligations under international law.

Since 2010, federal prosecutors have charged about 60 former agents of the dictatorship with killings, kidnappings, and other serious crimes. Lower courts have dismissed most of the cases, citing either the amnesty law or the statute of limitations.

In May 2020, a federal court dismissed charges against people involved in the torture and killing of journalist Vladimir Herzog in 1975. Prosecutors had re-opened the investigation in compliance with a 2018 ruling by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights.

In September, German company Volkswagen admitted its representatives had cooperated with Brazil’s dictatorship. Brazil’s National Truth Commission had found in 2014 that company representatives had provided information about its workers to authorities, which might have resulted in illegal arrests, torture, and other abuses. As part of a settlement agreement with Brazilian prosecutors, Volkswagen agreed to pay 36 million reais (approximately US$6.5million) in compensation to victims and to fund efforts to identify the remains of victims and to educate the public about past abuses.

President Bolsonaro has repeatedly praised the dictatorship. In October his vice-president, a retired general, expressed his admiration for a late colonel identified as commander of a torture center.

Key International Actors

The United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights has expressed concern over attacks against human rights defenders, the downplaying of Covid-19 by “political leaders,” and increased involvement of the military in public affairs and law enforcement.

Five UN rapporteurs said President Bolsonaro has minimized human rights violations during the dictatorship and spread “misinformation” about the military regime.

Some European leaders, the European Parliament, and several national parliaments across Europe have expressed strong reservations about ratifying a pending trade agreement between the European Union and Mercosur. They have noted that Bolsonaro’s environmental policies call into question Brazil’s readiness to implement the deal’s environmental commitments to fight deforestation and uphold the Paris Climate Agreement.

Brazil endorsed the World Health Organization’s Solidarity Call to Action for the Covid-19 Technology Access Pool, an initiative to “realize equitable global access to COVID-19 health technologies through pooling of knowledge, intellectual property and data.”

Foreign Policy

In 2019, Brazil ran for one of two vacant seats on the UN Human Rights Council along with Venezuela, with Costa Rica presenting its candidacy shortly before the election. Venezuela’s narrow win was likely facilitated by Brazil lobbying Latin American countries against presenting a third candidate.

In 2020, Brazil’s Foreign Ministry pressed for exclusion of references to “sexual and reproductive health” in UN resolutions, which it said could “give a positive connotation to abortion.” For instance, by resisting a UN resolution—which nevertheless passed in July—Brazil opposed affirming the rights to universal access to “sexuality education,” “safe abortion where not against national law,” and “post-abortion care.”