São Paulo, January 27, 2021

Permanent Representatives of Member States Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)

Dear Ambassadors,

As the OECD Environment Policy Committee (EPOC) prepares to review Brazil’s status with the committee at its upcoming meeting in February, we are urging member states’ delegations to examine the environmental and human rights impacts of President Jair Bolsonaro’s disastrous policies in the Amazon, which we believe should disqualify Brazil from a status upgrade at this time.

EPOC’s mandate includes supporting “the development of policies aiming at protecting and restoring the environment as well as responding to major environmental issues and threats.” It also includes ensuring that “the views and expertise of non-government institutions are drawn upon in the conduct of OECD’s environmental work.”[1]

The Bolsonaro administration, however, has actively and openly worked against these objectives. It has sabotaged Brazil’s environmental law enforcement agencies, falsely accused civil society organizations of environmental crimes and sidelined them from policymaking, and sought to undermine Indigenous rights. As we detail in the attached briefing document, these policies have contributed to soaring deforestation rates in the Brazilian Amazon, an ecosystem vital for containing global warming.

President Bolsonaro’s rhetoric and actions have effectively given a green light to criminal networks that are driving much of the deforestation. These mafias engage in acts of violence and intimidation against Brazilian forest defenders, including environmental enforcement agents, Indigenous communities, and other local residents. The fires that they and others set to clear deforested land produce pollution that poisons the air breathed by millions of Brazilians, taking a grave toll on public health in the region. Those responsible for the environmental crimes, violence, and fires are almost never brought to justice.

If OECD member states were to upgrade Brazil’s EPOC status while the Bolsonaro government is so flagrantly flouting the principles espoused by the committee in its mandate – with devastating consequences for the environment and human rights in the Amazon – it would undermine the credibility of the EPOC’s commitment to these principles. It would also send a discouraging message to the many Brazilians who are facing violence and intimidation in retaliation for their efforts to preserve the world’s largest rainforest.

More broadly, in future discussions on Brazil’s request for OECD accession, we urge you to pay close attention to the Bolsonaro’s administration’s record with regard to environmental policies, deforestation, and respect for the rights of forest defenders and Indigenous peoples. OECD member states should send a clear signal to the Bolsonaro government that they will not support Brazil’s candidacy unless its current policies on those issues radically change to protect the environment and support its defenders, and until Brazil demonstrates concrete results in reducing deforestation and lawlessness in the Amazon.

Sincerely,

Anna Livia Arida

Deputy Director

Brazil Human Rights Watch

Daniel Wilkinson

Acting Director Environment and Human Rights

Human Rights Watch

Environmental Setbacks Under the Bolsonaro Administration

I. Deforestation

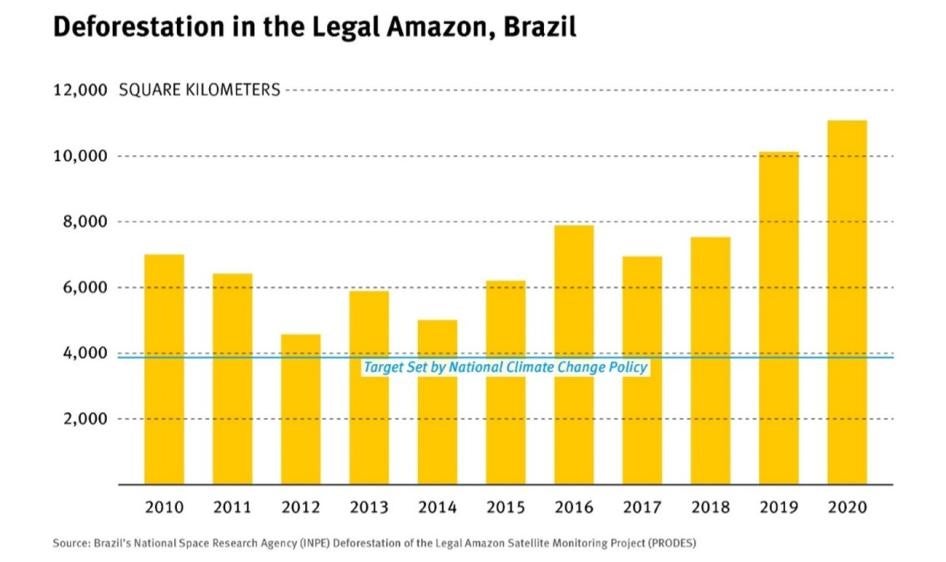

Since President Bolsonaro took office in 2019, deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon has increased dramatically. The increase was more than 30 percent during the first year of his administration and an additional 9.5 percent during the second year, according to official figures.[2] Last year, over 11,000 square kilometers of rainforest were lost, nearly triple the 3,925 square kilometers target that Brazil committed itself to reaching by 2020 as part of its National Climate Change Policy.[3] Overall, deforestation under President Bolsonaro has reached the highest level over the past decade.

The accelerated destruction of the Brazilian Amazon could have devastating consequences for the region and global efforts to mitigate climate change. Scientists estimate that 17 percent of all the Amazon has already been deforested. If the current rate of destruction continues, between 20 and 25 per cent of the rainforest could be cleared in under two decades, pushing the Amazon towards a tipping point when vast portions of the rainforest would turn into dry savannah, decimating Brazilian agriculture, altering weather patterns and water cycles across South America, and releasing billions of tons of carbon into the atmosphere.[4]

- Official Deforestation Figures

The Deforestation of the Legal Amazon Satellite Monitoring Project (PRODES), a system run by Brazil’s National Space Research Agency (INPE), produces annual official estimates of clear-cut deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon through analysis of satellite imagery.[5] The consolidated figure covers the 12-month period from August of the previous year through July (it does not provide month-to-month estimates). As evidenced by PRODES figures, deforestation under President Bolsonaro is significantly higher than any other year over the past decade (see graph below).

The Real-Time Deforestation Detection System (DETER), operated by INPE, provides near real-time alerts of deforestation based on satellite imagery to guide environmental enforcement efforts. The alerts are an indication of deforestation but, because of cloud cover and other factors, they often underestimate total deforestation in relation to PRODES. Unlike PRODES, however, DETER does provide daily and monthly estimates of deforestation. DETER monthly estimates show that over two thirds of the deforestation in the period between August 2018 and June 2019 took place after President Jair Bolsonaro took office.[6]

II. Forest Fires

Forest fires are closely linked to deforestation in Brazil. They do not occur naturally in the wet ecosystem of the Amazon basin, but rather are frequently started by people completing the process of deforestation where the trees of value have already been removed, often illegally. A total of 55 percent of the area cleared in the rainforest in 2019 was burned, equivalent to over 5,500 square kilometers.[7] Data is not available for the area deforested and burned in 2020, but the number of fires detected in 2020 increased by 15,7 percent in relation to 2019.[8]

The impact of these fires extends beyond the deforested lands when they spread to the remaining forest, destroying healthy trees, and opening up the overstory. This enables more sunlight to penetrate the forest, drying up vegetation on the ground and making it more flammable, leaving the forest more vulnerable for the next burning season.

In addition to the environmental consequences, the forest fires linked to deforestation produce air pollution that has a significant negative impact on public health in the Amazon region. In 2019, the pollution from the fires led to 2,195 hospitalizations due to respiratory illness, according to a report by Human Rights Watch, the Instituto de Pesquisa Ambiental da Amazônia (IPAM) and the Instituto de Estudos para Políticas de Saúde (IEPS) that analyzed official health and environmental data.[9]

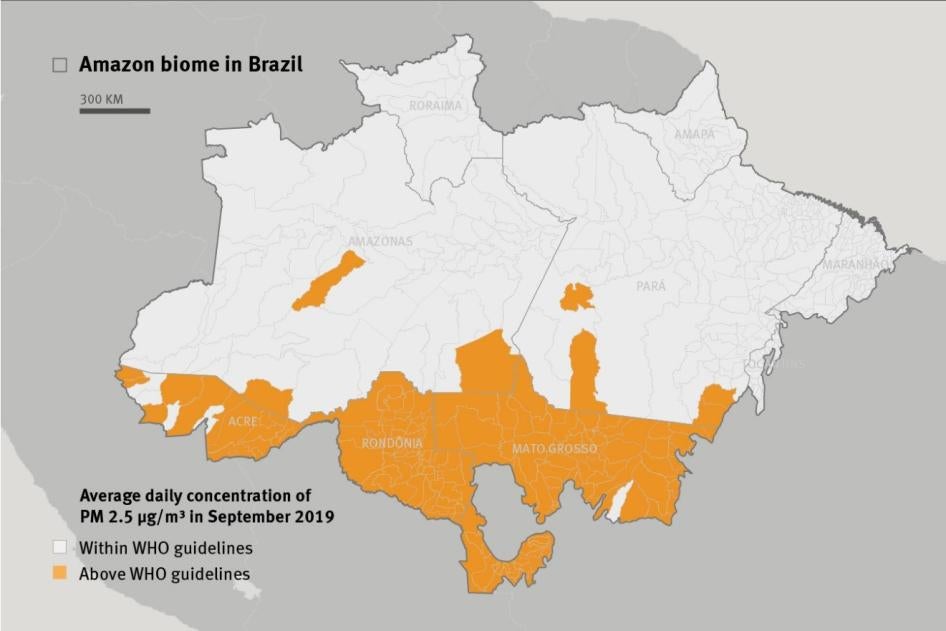

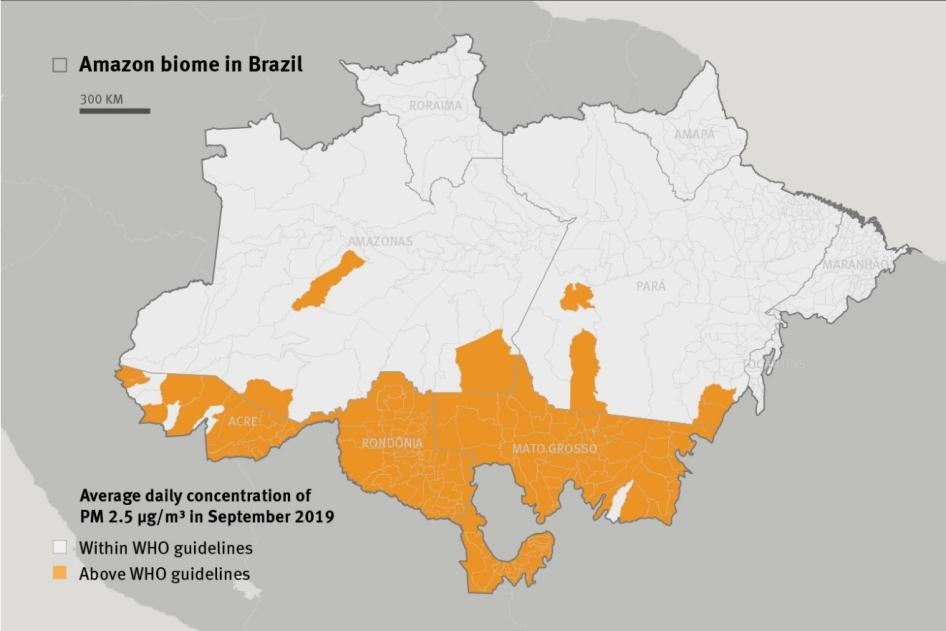

Hospitalizations are a small fraction of the overall health toll of the fires. In total, the air pollution affected millions of people. In August 2019, nearly 3 million people in the Amazon region were exposed to harmful air pollution levels above the World Health Organization’s recommended threshold. The number increased to 4.5 million people in September, the report showed (see graphs below). [10]

III. Weakened Environmental Agencies

Since President Bolsonaro took office in 2019, his administration has moved aggressively to undermine the enforcement of environmental laws in Brazil.

- The Bolsonaro administration has weakened the country’s main federal environmental enforcement agency, the Brazilian Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA). Shortly after beginning his term, at an agribusiness fair attended by landowners, President Bolsonaro said he had ordered Environment Minister Salles to “clean out” IBAMA.[11] Subsequently, Minister Salles removed 21 of the 27 regional directors who were responsible for anti-logging operations, marking the largest such removal in the institution’s thirty-year history.[12] An inspection by a federal oversight body concluded that several of the replacements appointed by Salles did not meet the minimum requirements for the positions they filled; these included the new directors for Mato Grosso, Pará–Brazil’s largest timber producers–and four other Amazon states.[13]

- In 2009, IBAMA employed some 1,600 inspectors throughout Brazil. While numbers have declined over the years, the Bolsonaro administration has made aggressive cuts: in 2019, when he took office, IBAMA employed 780 inspectors, in 2020 it employed 667.[14] Inspectors conduct field monitoring and are deployed for environmental law enforcement, including fining loggers and confiscating their equipment. Only a fraction of these inspectors is devoted to the Amazon region, leaving large swaths of the rainforest with limited presence of inspectors. For instance, in May 2019 there were only eight IBAMA inspectors for the western half of Pará – an area almost as big as France – an IBAMA official informed Human Rights Watch.[15]

- In addition to being severely understaffed, environmental agencies are also facing historic budgetary cuts. The 2021 budget proposed by the federal government for its environmental agencies is the lowest in 13 years, according to data from the Brazilian transparency research center Contas Abertas. The government’s budget proposal for the Environment Ministry, the agencies under its administration and other environment-linked expenditures programs is 2.9 billion reais (US$530.50 million). That represents a 5.4% drop from the government’s budget proposal for environmental protection last year, down to the lowest level in the Contas Abertas analysis going back to 2008.[16]

- The government has also imposed strict restrictions on environmental agencies’ ability to share information directly with the media, undermining accountability and transparency. In March 2019, news reports stated that Minister Salles had decided that the Environment Ministry would manage the press requests addressed to IBAMA and another environmental enforcement agency, interfering with the autonomy of these two federal bodies. (Minister Salles had previously also dismissed IBAMA’s head of communications.)[17] Subsequently, in March 2020, the president of IBAMA– an appointee of Minister Salles–required that IBAMA officials report any attempt by a journalist to contact them.[18]

- In February 2020, President Bolsonaro issued a decree creating an ‘Amazon Council’ charged with protecting the rainforest.[19] The vice-president, a retired army general, presides over the council and has the authority to make all final decisions, side-lining seasoned environmental officials to secondary roles.[20] As part of the move to centralize command control in the Amazon Council, in May 2020 the federal government transferred responsibility for leading environmental enforcement efforts in the Amazon from IBAMA and other environmental agencies to the armed forces, which do not possess the technical expertise nor training necessary to fulfill this role.[21]

- The armed forces have been largely ineffective at significantly curbing environmental destruction of the Brazilian Amazon. The extension of public forests illegally deforested was 2,265 square kilometers in 2020, in comparison to an average of 1,128 square kilometers between 2014 and 2018, indicating a surge in invasions of public lands under the army’s watch.[22] The number of fires detected in the Amazon in 2020 was 15.7 percent higher than in 2019, despite a decree issued by the federal government in mid-July prohibiting the burning of vegetation in the Amazon for four months.[23]

IV. Impunity for Environmental Destruction

The Bolsonaro administration also moved to reduce the sanctions faced by those caught engaging in illegal logging and other environmental crimes.

- Under the Bolsonaro administration, the number of environmental fines issued by IBAMA for illegal deforestation and other environmental infractions has dropped dramatically. In previous years, IBAMA had issued an average of 16,000 fines every year. In 2019, it issued only 11,914. In 2020, that number dropped to 9,516, the lowest in 20 years, and 40 percent below the average.[24] President Bolsonaro publicly celebrated the decrease in fines and promised these would continue to be slashed: “in the first two months of this year we had the least fines issued in the field and these will continue to diminish,” he said in June 2019, “we will end this fine factory.”[25]

- In addition to issuing fewer fines, the Bolsonaro administration effectively stopped enforcing them. In October 2019, it implemented new procedures establishing that environmental fines should be reviewed at “conciliation hearings,” in which a commission can offer discounts or eliminate the fine altogether. The Environment Ministry suspended all deadlines to pay those fines until a hearing could be held. Between October 2019 – when the decree came into force – and November 2020, federal environmental agencies held only five such conciliation hearings.[26] In practice, this means that the requirement to pay for nearly all the fines imposed during that period of more than a year was effectively suspended. In November 2020, the Ministry of Environment established through a new ordinance that those fined for environmental infractions would have 30 days to opt for the conciliation hearing; if there is no interest in attending a hearing, deadlines to pay or challenge the fine must resume. The new system will have to contend with a backlog of thousands of unpaid fines.[27]

V. Undermining Protection of Indigenous Territories

The demarcation and protection of Indigenous territories has been a cornerstone of successful conservation efforts in the Amazon, as well as a fundamental step toward the recognition and respect of Indigenous rights.[28] Under the Bolsonaro administration, illegal incursions and environmental destruction within these areas have greatly increased, encouraged by the president’s rhetoric and actions to undermine oversight of these territories.[29]

- Since President Bolsonaro took office in January 2019, the federal government has not demarcated any new Indigenous territories, even though the constitution requires it to demarcate and protect such territories (there are currently 237 pending requests for demarcation).[30] President Bolsonaro vowed not to designate “one more centimeter” of land as Indigenous territory and tabled a bill in Congress to open up Indigenous land to mining and other commercial enterprises.[31]

- In April 2019, the Bolsonaro government eliminated by decree the committee to implement the National Policy of Environmental and Land Management in Indigenous Territories, designed to promote environmental protection in Indigenous territories.[32]

- During President Bolsonaro’s first year in office, there was a 135 percent increase in illegal invasions, illegal logging, land grabbing, and other infringement upon Indigenous areas, according to the Indigenist Missionary Council (CIMI), a non-profit organization.[33]

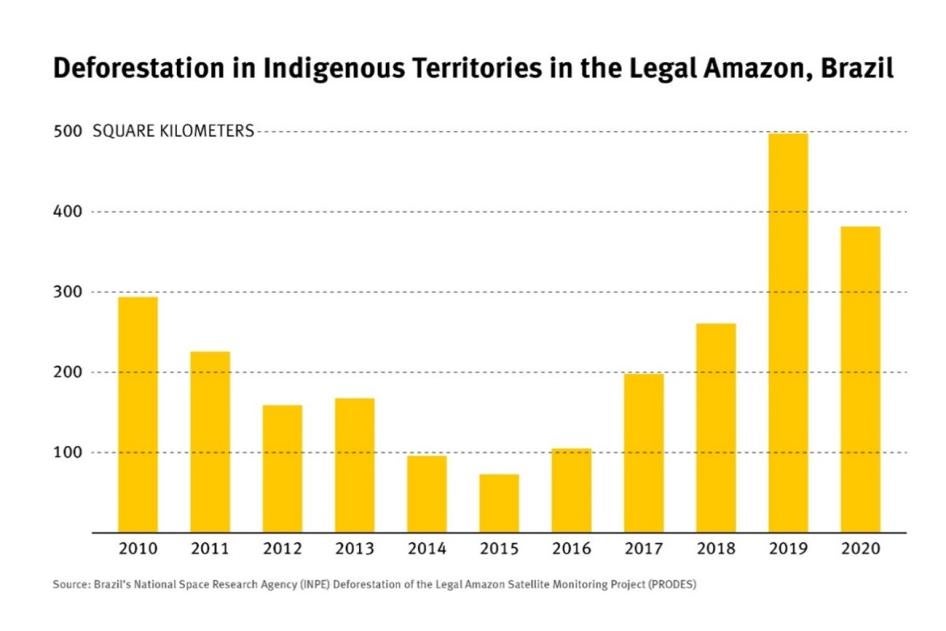

- Under Bolsonaro, deforestation in Indigenous lands is higher than it has been over the past ten years, and 2019 marked the worst year since Brazil began monitoring deforestation in Indigenous territories, according to data from INPE.[34] While 2020 registered a decrease compared to the 2019 peak, deforestation in Indigenous territories remained significantly higher than in previous years on record (see graph below).

VI. Impunity for Violence Against Forest Defenders

- A 2019 report by Human Rights Watch documented criminal networks engaged in illegal deforestation in the Amazon use violence and intimidation against anyone who threatens their illegal activities, including against enforcement agents and members of local communities.[35]

- Impunity for these and other acts of violence in the Amazon is the norm. During a decade, more than 300 people were killed in conflicts over the use of land and resources in Amazonian states — many of them by people involved in illegal deforestation — according to data provided to Human Rights Watch by the Pastoral Land Commission (CPT), a nonprofit organization that has offices across the country to provide legal and other aid to victims. Only 14 of these killings have ultimately gone to trial. Of the 28 killings that Human Rights Watch documented in our 2019 report, only two have gone to trial, and of the more than 40 cases of threats, none did.

VII. Corruption Linked to Environmental Destruction

- Corruption and money-laundering facilitate environmental crimes and undermine enforcement of environmental regulations. Therefore, addressing environmental crimes effectively requires not only solid environmental governance but also strong anti-corruption institutions.[36]

- In the states of Mato Grosso and Pará, Brazil’s two main producers of timber, 39% and 70% respectively of timber production exploitation is carried out in violation of logging regulations and laws, studies by Brazilian environmental research centers have shown.[37] Environmental crimes such as these are made possible by widespread fraud in Forest Management Plans and forged documentation that misrepresents the origin of timber, major investigations by the Office of the Federal Prosecutor suggest.[38] Those investigations indicate that these “timber laundering” schemes were facilitated by corrupt public servants who allegedly received bribes in exchange for approving fraudulent documents or turning a blind eye to environmental crimes.[39]

- There have been significant setbacks in anti-corruption governance under the Bolsonaro administration, according to Transparency International Brazil, including growing political interference in the bodies responsible for preventing and combating corruption and money-laundering. [40]

- The Bolsonaro administration has also dismantled transparency and participatory governance mechanisms. For instance, it reduced civil society representatives in the National Council for the Environment (CONAMA) and the Climate Fund’s steering committee.[41] Meanwhile, high-level officials – including the president and vice-president – have questioned the data on deforestation produced by INPE, without producing evidence of any inaccuracies in the data from the government’s own institution, in an apparent attempt to reduce transparency on pressing environmental issues.[42]

VIII. Hostility Toward Civil Society

- President Bolsonaro called NGOs working in the Amazon a “cancer” that he “can’t kill,” and accused them, without any proof, of being responsible for the destruction of the rainforest. He also blamed Indigenous people and small farmers, again without evidence, for Amazon fires.[43]

- In September 2020, Environment Minister Ricardo Salles petitioned a federal court to order a leading environmental defender to explain comments criticizing the minister, a measure seemingly intended to intimidate the defender.[44] Previously, Salles took the same measure to target a scientist from INPE who publicly referred to the minister’s conviction for administrative misconduct in an interview about deforestation in the Amazon, according to press reports.[45]

- In October 2020, media reported that the Bolsonaro administration had deployed the country’s secret service to spy on the Brazilian delegation, NGOs, and others at the December 2019 UN Climate Change Conference in Madrid.[46]

[1] Resolution of the Council revising the Mandate of the Environment Policy Committee [C(2018)139] approved by the Council on 29 October 2018 at its 1383rd session [C/M(2018)20, item 216] https://oecdgroups.oecd.org/Bodies/ShowBodyView.aspx?BodyID=1546&BodyPID=12223&Lang=en&Book=False (accessed January 14, 2021).

[2] For annual deforestation data, see National Space Research Agency of Brazil (INPE), “Monitoramento do Desmatamento da Floresta Amazônica Brasileira por Satélite,” http://www.obt.inpe.br/OBT/assuntos/programas/amazonia/prodes/prodes (accessed January 26, 2021), and “Nota técnica: Estimativa do PRODES,” 2020 http://www.obt.inpe.br/OBT/noticias-obt-inpe/estimativa-de-desmatamento-por-corte-raso-na-amazonia-legal-para-2020-e-de-11-088-km2/NotaTecnica_Estimativa_PRODES_2020.pdf (accessed January 14, 2021).

[3] Brazil pledged at the 2009 United Nations Climate Change Conference, known as the Copenhagen Summit, to reduce deforestation in the Amazon region by 80 percent by 2020 compared to average annual deforestation in the region between 1996 and 2005. That average was 19,625 square kilometers, which means that to achieve its pledge, Brazil would have to reduce deforestation to 3,925 square kilometers per year by 2020. Brazil established a National Policy on Climate Change by law in 2009, implemented by Decree 7,390 in 2010, which was replaced by Decree 9,578 in 2018. The decrees incorporated into domestic law the pledge that Brazil made at the Copenhagen Summit. Law 12,187, December 29, 2009, http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2007-2010/2009/lei/l12187.htm (accessed June 30, 2019); Decree 9,578, November 22, 2018, http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2015-2018/2018/Decreto/D9578.htm (accessed January 26, 2021). For the deforestation data, see National Space Research Agency of Brazil (INPE), Nota técnica: Estimativa do PRODES, 2020 http://www.obt.inpe.br/OBT/noticias-obt-inpe/estimativa-de-desmatamento-por-corte-raso-na-amazonia-legal-para-2020-e-de-11-088-km2/NotaTecnica_Estimativa_PRODES_2020.pdf (accessed January 14, 2021).

[4] Thomas E. Lovejoy and Carlos Nobre, “Amazon Tipping Point”, Nature, Science Advances 21 Feb 2018:

Vol. 4, no. 2, https://advances.sciencemag.org/content/4/2/eaat2340 (accessed January 25, 2021); Thomas E. Lovejoy and Carlos Nobre, “Amazon tipping point: Last chance for action,” Science Advances 20 Dec 2019:Vol. 5, no. 12, https://advances.sciencemag.org/content/5/12/eaba2949 (accessed January 25, 2021).

[5] Brazil’s “Amazon” refers to the area known as “Legal Amazon” under Law 1,806/1953 that includes the states of Acre, Amapá, Amazonas, Mato Grosso, Pará, Rondônia, Roraima, Tocantins, and the western part of Maranhão. (Law 1,806/1953).

[6] Between August and December 2018, there were 2,142.13 square kilometers clear cut in the Legal Amazon, in comparison to 4,701.78 between January and July 2019, when President Bolsonaro was in office. See INPE’s DETER figures: http://terrabrasilis.dpi.inpe.br/app/dashboard/alerts/legal/amazon/aggregated/ (accessed January 26, 2021).

[7] Moutinho, P., Alencar, A., Arruda, V., Castro,I., e Artaxo, P., “Nota técnica nº 3: Amazônia em Chamas - desmatamento e fogo em tempos de covid-19,” Instituto de Pesquisa Ambiental da Amazônia, Brasília, 2020, https://ipam.org.br/bibliotecas/amazonia-em-chamas-4-desmatamento-e-fogo-em-tempos-de-covid-19-na-amazonia/ (accessed July 20, 2020).

[8] DW, Brasil encerra 2020 com maior número de focos de queimadas em uma década, January 3, 2021, https://www.dw.com/pt-br/brasil-encerra-2020-com-maior-n%C3%BAmero-de-focos-de-queimadas-em-uma-d%C3%A9cada/a-56119157 (accessed January 15, 2021).

[9] Human Rights Watch, IPAM, IEPS, “ ‘The Air is Unbearable’: Health Impacts of Deforestation-Related Fires in the Brazilian Amazon,” August 2020, https://www.hrw.org/report/2020/08/26/air-unbearable/health-impacts-deforestation-related-fires-brazilian-amazon

[10] Human Rights Watch, IPAM, IEPS, “ ‘The Air is Unbearable’: Health Impacts of Deforestation-Related Fires in the Brazilian Amazon,” August 2020, https://www.h-rw.org/report/2020/08/26/air-unbearable/health-impacts-deforestation-related-fires-brazilian-amazon

[11] “Bolsonaro diz que negociou com ministro do Meio Ambiente 'uma limpa' no IBAMA e no ICMBio,” G1, April 29, 2019, https://g1.globo.com/sp/ribeirao-preto-franca/noticia/2019/04/29/bolsonaro-diz-que-negociou-com-ministro-do-meio-ambiente-uma-limpa-no-ibama-e-no-icmbio.ghtml (accessed June 19, 2019).

[12] “Ricardo Salles exonera 21 dos 27 superintendentes regionais do Ibama,” Folha de São Paulo, February 28, 2019, https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/ambiente/2019/02/ricardo-salles-exonera-21-dos-27-superintendentes-regionais-do-ib.shtml

[13] The evaluation was conducted by Brazil’s Federal Court of Accounts (TCU), which is responsible for the accounting, financial, budgetary, operational and patrimonial inspection of public bodies and entities in the country as to legality, legitimacy and economy, see TCU, Institucional: https://portal.tcu.gov.br/institucional/conheca-o-tcu/competencias/ (accessed January 26, 2021). The news outlet Estadao obtained the TCU report and published its conclusions; see André Borges, “Nomeações de militares por Salles no Ibama são irregulares, aponta auditoria do TCU,” Estadao, November 11, 2020, https://politica.estadao.com.br/noticias/geral,nomeacoes-de-militares-por-salles-no-ibama-sao-irregulares-aponta-auditoria-do-tcu,70003510029 (accessed January 26, 2021). The other regional directors evaluated and deemed unsuitable were in Amapá, Amazonas, Maranhão and Rondônia.

[14] The 1,600 inspectors in 2009 and the 780 in 2019 included field agents and others who work borders and airports. Human Rights Watch interviews with Suely Araújo, then IBAMA president, Brasília, April 3, 2018; and Luciano Evaristo, then director of director of environmental protection at IBAMA, Brasília, April 3, 2018. Open letter by IBAMA agents to IBAMA president, August 26, 2019, copy on file at Human Rights Watch. Letter from IBAMA staff to IBAMA president Eduardo Bim, July 21, 2020, http://www.ascemanacional.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/SEI_IBAMA-8011719-Manifestac%CC%A7a%CC%83o-Te%CC%81cnica.pdf (accessed January 1, 2021).

[15] Human Rights Watch interview with a high-level IBAMA official, Pará, May 3, 2019. He asked that his identity be kept confidential because he did not have authorization from his superiors to speak publicly.

[16] Jake Spring, “Brazil proposes cuts to 2021 budget for environmental protection as deforestation spikes,” Reuters, January 25, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-brazil-environment/brazil-proposes-cuts-to-2021-budget-for-environmental-protection-as-deforestation-spikes-idUSKBN29U26S (accessed January 26, 2021).

[17] Fernando Tadeu Moraes, “Ministério do Meio Ambiente impõe mordaça ao Ibama,” Folha de Sao Paulo, March 13, 2019, https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/ambiente/2019/03/ministerio-do-meio-ambiente-impoe-mordaca-ao-ibama.shtml (accessed January 26, 2021). Ordinance n° 202, March 11, 2019, https://www.in.gov.br/web/dou/-/portaria-n-202-de-11-de-marco-de-2019-66758558 (accessed January 26, 2021).

[18] Leandro Prazeres, “Presidente do Ibama publica portaria e restringe contato de funcionários com a imprensa,” O Globo, March 5, 2020, https://oglobo.globo.com/sociedade/presidente-do-ibama-publica-portaria-restringe-contato-de-funcionarios-com-imprensa-24288119 (accessed January 26, 2021).

[19] Decree n° 10,239/2020, February 11, 2020, Art. 3, http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2019-2022/2020/Decreto/D10239.htm (accessed June 5, 2020).

[20] Rubens Valente, “Mourão forma Conselho da Amazônia com 19 militares e sem Ibama e Funai,” UOL, April 18, 2020. https://noticias.uol.com.br/colunas/rubens-valente/2020/04/18/conselho-amazonia-mourao.htm (accessed June 5, 2020).

[21] Human Rights Watch World Report 2021, Brazil, https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2021/country-chapters/brazil#

[22] Instituto de Pesquisa Ambiental da Amazônia (IPAM), “Desmatamento em florestas públicas da Amazônia explode em dois anos,” December 16, 2020, https://ipam.org.br/desmatamento-em-areas-griladas-nas-florestas-publicas-da-amazonia-explode-em-dois-anos/ (accessed January 26, 2021). See also: Claudia Azevedo-Ramosa, Paulo Moutinho, Vera Laísa da S. Arruda, Marcelo C.C. Stabile, Ane Alencar, Isabel Castro, João Paulo Ribeiro, “Lawless land in no man’s land: The undesignated public forests in the

Brazilian Amazon,” Land Use Policy 99, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104863 (accessed January 25, 2020).

[23] DW, Brasil encerra 2020 com maior número de focos de queimadas em uma década, January 3, 2021, https://www.dw.com/pt-br/brasil-encerra-2020-com-maior-n%C3%BAmero-de-focos-de-queimadas-em-uma-d%C3%A9cada/a-56119157 (accessed January 15, 2021).

[24] Between 2013 and 2017, IBAMA had issued an average of 16,000 fines every year, according to the Office of the Comptroller General, see: Fakebook.eco, “Sob Bolsonaro, multas do IBAMA caem para menor nível em duas décadas,” January 12, 2021, https://fakebook.eco.br/sob-bolsonaro-multas-do-ibama-caem-para-menor-nivel-em-duas-decadas/ (accessed January 15, 2021). Fakebook.eco is a fact-checking initiative of Observatório do Clima, a coalition of Brazil’s most prominent environmental organizations.

[25] Sabrina Rodrigues, “Bolsonaro: ‘O homem do campo não pode se apavorar com a fiscalização do Ibama,” Oeco, June 12, 2019, https://www.oeco.org.br/blogs/salada-verde/bolsonaro-o-homem-do-campo-nao-pode-se-apavorar-com-a-fiscalizacao-do-ibama/ (accessed January 26, 2021).

[26] In December 2019, Human Rights Watch filed a request before the Brazilian Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA) under the Access to Information Law, asking how many conciliation hearings had been held. In January 2020, IBAMA responded that there had not been any hearings. In April 2020, IBAMA’s media office responded in writing to a Human Rights Watch request for updated information. It said that only five conciliation hearings had been held by that date, and that due to the Covid-19 health emergency, all additional hearings had been suspended. In December 2020, following another information request under the Access to Information Law, IBAMA provided similar information and added that the hearings were resuming based on a new ordinance.

[27] Ordinance n° 589, November 27, 2020, https://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/portaria-conjunta-n-589-de-27-de-novembro-de-2020-290864787 (accessed January 25, 2021)

[28] International Labor Organization Convention No. 169, ratified by Brazil on July 24, 2002, https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=1000:11200:0::NO:11200:P11200_COUNTRY_ID:102571 (accessed January 27, 2021), Art. 14; UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, adopted by the UN General Assembly on September 13, 2007, including Brazil, https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/wp-content/uploads/sites/19/2018/11/UNDRIP_E_web.pdf (accessed January 27, 2021), Art. 8. Nepstad, Daniel, et al., “Slowing Amazon Deforestation through Public Policy and Interventions in Beef and Soy Supply Chains,” Science 344, 1118 (2014), DOI: 10.1126/science.1248525

[29] Human Rights Watch, “Rainforest Mafias: How Violence and Impunity Fuel Deforestation in Brazil’s Amazon,” September 17, 2019, https://www.hrw.org/report/2019/09/17/rainforest-mafias/how-violence-and-impunity-fuel-deforestation-brazils-amazon

[30] Daniel Biasetto, “Sob Bolsonaro, Funai e Ministério da Justiça travam demarcação de terras indígenas,” O Globo, January 3, 2021, https://oglobo.globo.com/brasil/sob-bolsonaro-funai-ministerio-da-justica-travam-demarcacao-de-terras-indigenas-24820597 (accessed January 25, 2021); Constitution of the Federative Republic of Brazil, 1988, art. 231, http://www.stf.jus.br/arquivo/cms/legislacaoConstituicao/anexo/brazil_federal_constitution.pdf (accessed June 22, 2019).

[31] Ernesto Londoño, “Jair Bolsonaro, on Day 1, Undermines Indigenous Brazilians’ Rights,” The New York Times, January 2, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/01/02/world/americas/brazil-bolsonaro-president-indigenous-lands.html (accessed June 5, 2020); Draft bill n° 191/2019, February 6, 2020, https://www.camara.leg.br/proposicoesWeb/fichadetramitacao?idProposicao=2236765 (accessed June 5, 2020); Maria Laura Canineu and Andrea Carvalho, “Bolsonaro's Plan to Legalize Crimes Against Indigenous Peoples,” UOL Noticias, https://noticias.uol.com.br/politica/ultimas-noticias/2020/03/01/artigo-proposta-de-bolsonaro-para-legalizar-crimes-contra-povos-indigenas.htm (accessed January 25, 2021).

[32] Human Rights Watch interview with an ICMBio official, Brasília, August 15, 2019. The official asked that his name be withheld for fear of reprisals.

[33] Rubens Valente, “Invasões em terras indígenas sobem 135% no 1º ano de Bolsonaro, diz Cimi,” UOL, September 30, 2020, https://noticias.uol.com.br/colunas/rubens-valente/2020/09/30/indigenas-relatorio-violencia-brasil-governo-bolsonaro.htm (accessed January 26, 2021).

[34] Carolina Dantas, “Terra indígena mais desmatada do Brasil tem 6º ano seguido de alta; veja os 10 territórios mais afetados,” G1, December 1, 2020, https://g1.globo.com/natureza/noticia/2020/12/01/terra-indigena-mais-desmatada-do-brasil-tem-6o-ano-seguido-de-alta-veja-os-10-territorios-mais-afetados.ghtml (accessed on January 21, 2021). http://www.observatoriodoclima.eco.br/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Relato%CC%81rio-COP25-Ajustes-v3.pdf

[35] Human Rights Watch, “Rainforest Mafias: How Violence and Impunity Fuel Deforestation in Brazil’s Amazon,” September 17, 2019, https://www.hrw.org/report/2019/09/17/rainforest-mafias/how-violence-and-impunity-fuel-deforestation-brazils-amazon

[36] Prominent actors in the anticorruption field such as the United Nations Convention against Corruption (https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/corruption/COSP/session8-resolutions.html), the Financial Action Task-Force (https://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/German-Presidency-Priorities.pdf) or the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crimes (https://www.unodc.org/documents/southeastasiaandpacific//indonesia/publication/Corruption_Environment_and_the_UNCAC.pdf) have advocated for the mobilization of anti-corruption and anti-money laundering instruments to fight environmental crimes and have made such issues priorities for their action.

[37] ICV, “Mapeamento da ilegalidade na exploração madeireira em Mato Grosso entre agosto de 2016 e julho de 2017,” 2019. https://www.icv.org.br/drop/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/2019-transparenciaflorestal-madeirailegal.pdf (accessed January 22, 2021); Imazon, “Sistema de Monitoramento da Exploração Madeireira (Simex): Estado do Pará 2017-2018,” 2020. https://imazon.org.br/publicacoes/sistema-de-monitoramento-da-exploracao-madeireira-simex-estado-do-para-2017-2018/ (accessed January 22, 2021).

[38] See for instance: Federal Attorney General’s Office (MPF), Operação Arquimedes, 2019 http://www.mpf.mp.br/grandes-casos/operacao-arquimedes/entenda-o-caso. (accessed January 22, 2021); Federal Attorney General’s Office (MPF), Operação Floresta Virtual, 2017 http://www.mpf.mp.br/grandes-casos/ft-amazonia/frentes-de-atuacao/combate-ao-desmatamento/operacao-floresta-virtual (accessed January 22, 2021).

[39] Federal Police (PF), “PF desarticula quadrilha de exploração ilegal de madeiras em Rondônia,” October 25, 2019, http://www.pf.gov.br/imprensa/noticias/2019/10/pf-desarticula-quadrilha-de-exploracao-ilegal-de-madeiras-em-rondonia (accessed January 22, 2021).

[40] Transparência Internacional – Brasil, “Brazil: Setbacks in the Legal and Institutional Anti-Corruption Frameworks – 2020 Update,” 2020, https://transparenciainternacional.org.br/retrocessos/ (accessed January 22, 2021); Transparency International, “Brazil: Setbacks in the Legal and Institutional Anti-Corruption Frameworks,” 2019, https://images.transparencycdn.org/images/2019_Report_BrazilSetbacksAntiCorruptionFrameworks_English_191121_135151.pdf (accessed January 22, 2021).

[41] For Conama, see: Law 6,938 from August 31, 1981 created the CONAMA. Decree 99,274, from June 6, 1990, established that CONAMA would have 96 members, including representatives of federal, state, and municipal governments and 22 representatives of “workers and civil society.” Decree 9,806 from May 28, 2019 reduced the size of the council to 23 members and increased the relative representation of the federal government from 29 percent to 44 percent. Civil society was reduced to four seats, assigned by a lottery system for a one-year term. Civil society organizations previously had selected representatives to most of the seats reserved for civil society, and they were for a two-year term. Representação relativa à inconstitucionalidade do Decreto nº 9.806/2019” (Representation about the unconstitutionality of Decree No. 9.806/2019), Federal Prosecutor’s Office, August 28, 2019, p. 4, copy on file; See Law nº 8,080, September 19, 1990, Art. 13 and Art. 16, II, http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l8080.htm (accessed July 4, 2020). For the Climate Fund, see Law n° 12.114, December 9, 2009, http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2007-2010/2009/lei/l12114.htm (accessed January 18, 2021).

[42] BRANT, D. Bolsonaro critica diretor do Inpe por dados sobre desmatamento que 'prejudicam' nome do Brasil. Folha de São Paulo, 19 julho, 2019, https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/ambiente/2019/07/bolsonaro-critica-diretor-do-inpe-por-dados-sobre-desmatamento-que-prejudicam-nome-do-brasil.shtml : Gustavo Uribe, “Após dados negativos, Mourão diz que há oposição ao governo no Inpe,” Folha de São Paulo, September 15, 2020, https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/ambiente/2020/09/apos-dados-negativos-mourao-diz-que-ha-oposicao-ao-governo-no-inpe.shtml (accessed January 25, 2021).

[44] Human Rights Watch, “Brazil: Stop Harassing Environmental Defenders,” October 16, 2020, https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/10/16/brazil-stop-harassing-environmental-defenders

[45] Rubens Valente, “Com advogados da AGU, Salles interpela 4 pessoas por críticas à sua gestão,” UOL, November 24, 2020, https://noticias.uol.com.br/colunas/rubens-valente/2020/11/24/salles-interpelacao-judicial-agu-meio-ambiente.htm (accessed January 21, 2021).

[46] Human Rights Watch World Report 2021, Brazil, https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2021/country-chapters/brazil#