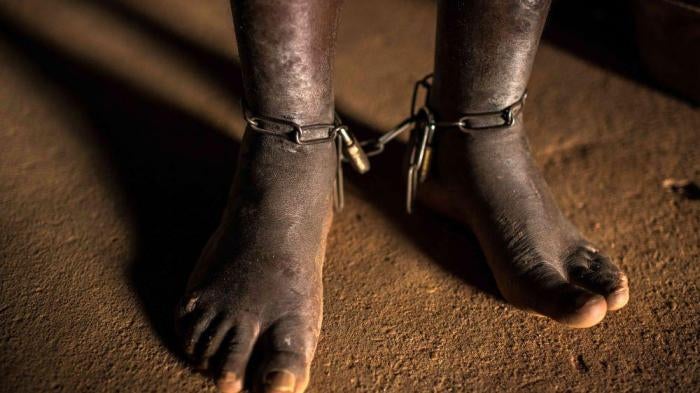

As the world grapples with the COVID-19 pandemic, certain images come to mind: quarantines in Wuhan and Italy, empty streets in France, and busy hospitals in the United States. While these images have flooded the media lately, others are less visible: men, women, and children laying on dirty floors or bare beds in overcrowded rooms, in ragged clothes or naked, a plastic bucket left for them to urinate and defecate in, and an iron chain fastened to their ankles.

This is the reality for hundreds of people we’ve spoken to across Nigeria who have, or are thought to have, mental health conditions. They are chained and locked up in various facilities, including state-run rehabilitation centers and psychiatric hospitals, and traditional and faith-based rehabilitation centers. They are shackled to heavy objects or to other detainees, in some cases for months or years. Many are physically and emotionally abused and forced to take questionable treatments.

As these images emerge, so do important questions. How are shackled people, crowded together, deprived of soap and water, supposed to protect themselves against COVID-19 infection? Will they receive treatment if they are infected? Or will the government continue to ignore them?

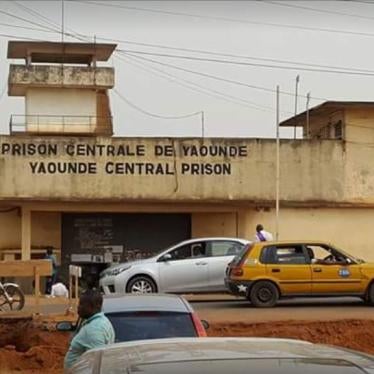

Nigeria’s healthcare system is plagued with chronic underfunding and limited infrastructure, and even in normal circumstances, many Nigerians have difficulty accessing healthcare. But people who are chained are likely to get little or no necessary healthcare, despite being at extreme risk.

As Nigeria prepares for the COVID-19 outbreak, the government should focus on those who are most at risk, including people with mental health conditions who are shackled across the country.

The risks of the pandemic for those in chains should be a wakeup call that Nigeria should end this practice, free people from chains, and ban shackling forever. The government should also make sure that people with mental health conditions held in any facility are included in government’s response to the pandemic, that they have access to information, to clean water and soap, are not forced to live close to others, and can access healthcare on an equal basis with others in Nigeria.