(Nairobi) – The Burundi authorities should immediately and unconditionally release four journalists and their driver arrested on October 22, 2019 while they were on a reporting trip to Bubanza Province for Iwacu newspaper.

The journalists had informed authorities of their plan to travel to the area to report on an outbreak in fighting between Burundian security forces and a group of assailants. But a police chief of operations arrested them while they were doing their jobs, Iwacu said in a statement on its website.

“Journalists play a vital role shedding light on incidents of public interest and should not be prosecuted for legitimate work,” said Lewis Mudge, Central Africa director at Human Rights Watch. “The authorities should reverse the current crackdown on media freedom and, as a first step, immediately release the journalists and their driver who are being detained for doing their jobs.”

As the 2020 elections approach next year, it is a source of great concern that the government continues to suppress the media and prevent journalists from doing their work, Human Rights Watch said.

Since the morning of October 22, social media accounts and exiled media organizations have shared reports of fighting near Kibira natural reserve, in Bubanza province, where the journalists were headed. The rebel group RED-Tabara (Mouvement de la Résistance pour un État de Droit au Burundi; Resistance Movement for the Rule of Law in Burundi), which was created in 2016 and operates in neighboring Democratic Republic of Congo, claimed responsibility on Twitter for the attack.

According to an SOS Médias Burundi report, the administration and security forces confirmed that 20 people were kidnapped – and later released – and that a policeman was killed. The Public Security Ministry said in a tweet that 14 “criminals” were killed.

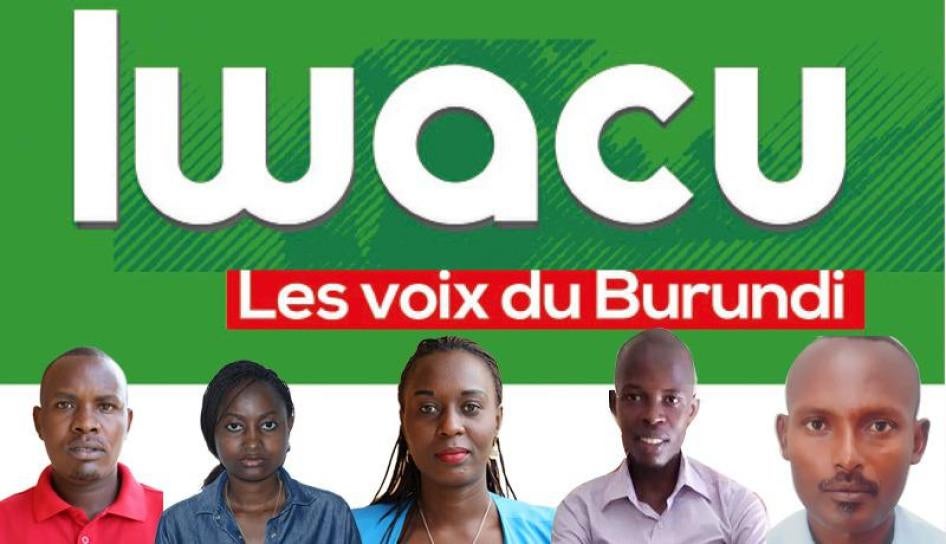

The four journalists – Christine Kamikazi, Agnès Ndirubusa, Egide Harerimana, and Térence Mpozenzi – and their driver, Adolphe Masabarakiza, were arrested in Musigati around midday and are being held in the Bubanza police station. On October 23, they were questioned by a judicial police officer at the police station in the presence of their lawyer. According to Iwacu, they have not yet been charged.

The National Independent Human Rights Commission, the CNIDH, a pro-government body, told Iwacu it was looking into the matter.

The government pressure on the news media has been growing. The National Communication Council (CNC) suspended the Voice of America (VOA) in May 2018 and renewed the suspension in March. It also withdrew the British Broadcasting Corporation’s (BBC) operating license in March, who closed down their office in Burundi in July. These draconian moves were among a series of government attempts to prevent the world from knowing about serious human rights abuses happening in Burundi.

The suspensions of both the BBC and the VOA began weeks before a controversial constitutional referendum in 2018, banning any journalist in Burundi from “providing information directly or indirectly that could be broadcast” by either the BBC or VOA.

Weeks earlier, the CNC had suspended Iwacu’s online comments section. At that time, Human Rights Watch found that Burundi’s security services and ruling party youth league members had killed, raped, abducted, beat, and intimidated suspected opponents in the months leading up to the referendum.

Scores of other Burundians have disappeared since a political crisis began in Burundi in April 2015 over President Pierre Nkurunziza’s decision to seek a third term. In many of these cases, the authorities make no efforts to identify people who have disappeared or to investigate when bodies resurface. The few independent journalists who remain put their lives on the line to uncover the truth, Human Rights Watch said.

Jean Bigirimana, a journalist with Iwacu, has been missing since July 2016. Unconfirmed reports indicated that intelligence service members arrested Bigirimana in Bugarama. Many other journalists are in exile.

“Journalists who have remained in Burundi are fighting hard to ensure that the world remains informed of situation on the ground,” Mudge said. “But by trying to cut off the supply of information at the source, the government is trying to operate without scrutiny or transparency.”