On February 28, Burundi’s government forced the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights to pack up and leave Burundi. This office had been working in Bujumbura since the 1990s and the violent intercommunal conflict that had left over 300,000 dead. It had helped build the country’s institutional human rights framework after this fratricidal war. The government’s order is the latest blow in an ongoing attack on human rights that began when President Pierre Nkurunziza announced in 2015 he was running for a controversial third presidential term. State security services and members of the Imbonerakure – the youth league associated with the ruling party – have killed, tortured, raped, arrested, beaten, and intimidated members of political opposition parties and others perceived as being against the government.

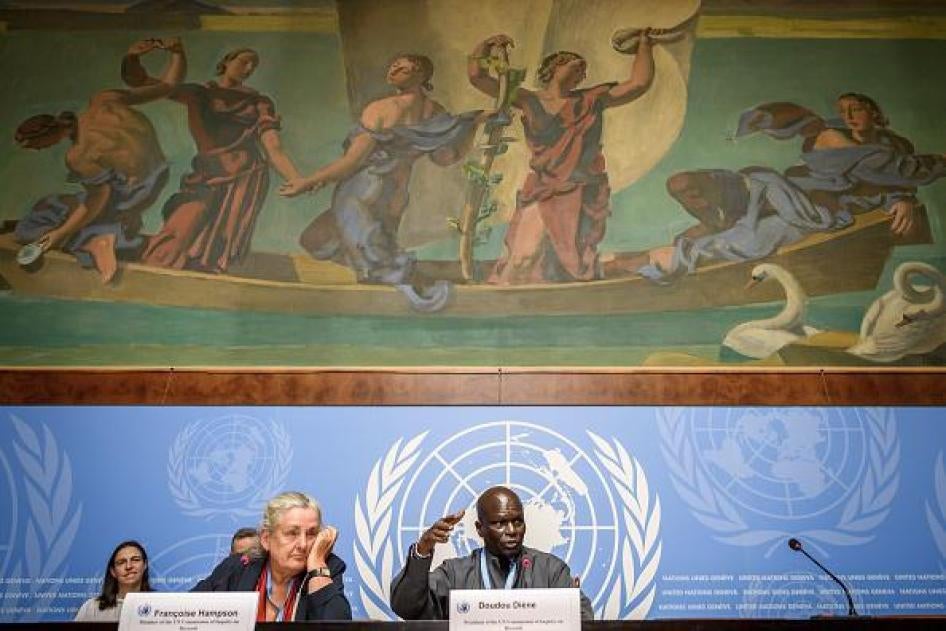

As part of its strategy, the government has done everything it can to keep the world in the dark on the situation in Burundi. But on Tuesday, March 12, the United Nations Commission of Inquiry on Burundi reported to the Human Rights Council, during its first session of the year, which is currently being held in Geneva, that to their knowledge, “the alleged perpetrators of grave violations and international crimes committed since 2015 have not been held accountable, and still occupy positions of authority within the security and defense forces and the Imbonerakure.”

But reporting what has been going on in Burundi has become a lot harder. Any Burundian who openly works on human rights issues is very likely to face arrest, detention or worse. So Burundi’s independent organizations and media must now work from the safety of exile. Every week, they compile and publish reports about new serious rights violations.

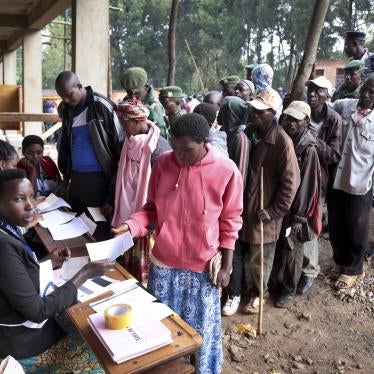

The government also banned international media and human rights organizations, or prevented them from entering the country. In September 2018, it suspended all international nongovernmental organizations including some that provide life-saving assistance, and ordered them to provide the “ethnic breakdown” of their national staff. This crossed a red line for many, fearing that the government intended to meddle in their operations or might even target people of certain community backgrounds on their staff. As a result, several groups left the country.

In this atmosphere, national institutions have failed to document the repression, much less to attempt to curb it. The national human rights commission, which had shed light on government abuses and showed signs of independence before the crisis, now stays quiet. It was downgraded from “A” to “B” status in April 2018, when the UN body in charge of accrediting national human rights institutions said it had failed to speak out “in response to credible allegations of gross human rights violations having been committed by government authorities.”

Regional institutions have been unable to address the rights crisis. In 2016, the government blocked African Union (AU) observers from monitoring the human rights situation and since then the regional body has shied away from discussing it. The East African Community-led dialogue is at a stalemate, there is little interest in finding an alternative.

As abuses by state security forces became more widespread in 2016, Bujumbura had started procedures to withdraw from the International Criminal Court’s (ICC) jurisdiction. But the ICC had announced on October 25, 2017, two days before the withdrawal took effect that it would investigate crimes committed since April 2015, and retains jurisdiction over crimes committed in Burundi before its withdrawal.

The departure of the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights only one year ahead of 2020 elections – although its work is suspended since October 2016 – underscores the Burundian government’s continued attempts to shield itself from international scrutiny.

In 2018, Burundian authorities declared the UN Commission of Inquiry members persona non grata. In 2017, the government had already threatened legal action against its members. Despite the lack of direct access, the Commission has managed to collect evidence and report more damning findings, including crimes against humanity. On March 12, it urged the Council’s members to observe the 2020 electoral process with the “utmost vigilance.” At this time, it is the only international monitoring mechanism that is providing regular reports on the repression in Burundi.

The Commission highlighted cases of sexual violence “seemingly spurred by the general climate of impunity in the country” and the direct implication of members of the Imbonerakure in “the majority of violations documented by the Commission, including sexual violence.” Additionally, it raised concerns about the apparent extortion of the population, which is regularly asked for forced or supposedly voluntary financial and in-kind contributions to the 2020 elections, and the threats, intimidation and attacks against refugees that return voluntarily to Burundi.

The government’s representative responded to the Commission by publicly rejecting the oral update. This was not unexpected.

The government has even refused to work with three separate UN experts whose “technical assistance” mandate it endorsed. Instead, it revoked their visas and expelled them in May 2018. Until last December, Burundi’s government was a member of the Human Rights Council, a post that conferred a responsibility to cooperate with the UN’s mechanisms. In reality, it displayed as a Council member the same contempt for human rights that it practises at home.

The authorities are trying to write History by limiting information coming from the country. The lack of reporting on human rights abuses is not the result of peace or progress. Rather, the fearful silence stems from an absence of checks on unaccountable power. The government wants to keep the world in the dark about ongoing abuse. Bujumbura can close the doors of Burundi, but it won’t be able to hide the repression. As the Commission of Inquiry and the activists working from exile are showing, the latter is only growing worse. Now is not the time to look away.