(Brussels) – Burundi government forces and ruling party members have killed, beaten, and intimidated perceived opponents of a constitutional referendum set for a May 17, 2018 vote that would enable the president to extend his term in office, Human Rights Watch said today. The abuse reflects the widespread impunity for local authorities, the police, and members of the ruling party’s youth league, the Imbonerakure.

Since December 12, 2017, when President Pierre Nkurunziza announced the referendum, state agents and members of the Imbonerakure – “those who see from far” in Kirundi, the predominant language in Burundi – have used fear and repression to ensure the vote goes in Nkurunziza’s favor. The referendum would allow Nkurunziza, who is already serving a controversial third term, to prolong his rule until 2034.

“There is little doubt that the upcoming referendum will be accompanied by more abuses,” said Ida Sawyer, Central Africa director at Human Rights Watch. “Burundian officials and the Imbonerakure are carrying out violence with near-total impunity to allow Nkurunziza to entrench his hold on power.”

Human Rights Watch confirmed 19 cases of abuse since December 12, all apparently to press Burundians to vote yes on the referendum. They include the beating to death of one person who did not show a receipt proving he had registered to vote; the beating of another person in detention that may have resulted in his death; and arrests, beatings, and mistreatment of many others. Most were members of the political opposition party, the National Liberation Forces (Forces nationales de libération, FNL).

The actual scale of abuse is most likely significantly higher. Several credible sources told Human Rights Watch that these kinds of abuses have been common throughout the country. Media outlets have reported similar trends. On January 18, a political coalition known as Amizero y’Abarundi (“the hope of the Burundians”), made up largely of FNL members, announced that 42 of its members had been arbitrarily arrested since December 12.

But confirming details of abuse has become more difficult in the climate of fear engulfing the country. Since 2015, when the current crisis began as Nkurunziza announced his bid for a controversial third term, the country’s once vibrant independent media and nongovernmental organizations have been decimated, and more than 397,000 people have fled the country.

The new Human Rights Watch findings are based on interviews in February and March with more than 30 victims, witnesses, and others, who described a range of abuses in seven of Burundi’s 18 provinces.

A 20-year-old farmer and member of the FNL described what happened when he had a drink with a friend at a bar in Kirundo province in January: “We both agreed that we were going to vote against changing the constitution. An Imbonerakure heard us and he called his friends… Six Imbonerakure then came to the bar and beat us with sticks before taking us to the jail.” The man was detained for 15 days.

Under the Burundian electoral code, campaigning for the referendum begins 16 days before the referendum. The government has been clear that it will seek out and punish anyone perceived as campaigning against the referendum. In a speech on December 12, Nkurunziza warned that those who dared to “sabotage” the project to revise the constitution “by word or action” would be crossing a “red line.”

On February 13, the spokesman for the Public Security Ministry, Pierre Nkurikiye, said publicly, in reference to people arrested for allegedly encouraging others not to register, “This is a warning, a warning to anyone who by his actions or words is hindering this process … he will be immediately apprehended by the police, and brought to justice.”

Local authorities reinforced these threats. Videos circulated on social media show authorities encouraging people to be vigilant toward anyone who may be against the referendum. In one example, on January 27, Revocat Ruberandinzi, the ruling party representative in Butihinda commune, Muyinga province, declared in a meeting that was filmed and posted online: “Whoever will be caught instructing people to vote no on the constitution [referendum], bring them to us. Do you understand me? The OPJ [judicial police] will not get here; we will take him ourselves…” In another example, on February 13, Désiré Bigirimana, the administrator of Gashoho commune, Muyinga province, told a crowd, “Anyone who says anything against the ‘yes’ [vote] or against Peter [President Nkurunziza], beat him over the head, and call me once you have tied him up.”

Government officials have also openly told Burundians that they must vote yes. A resident of Kayogoro commune in Makamba province told Human Rights Watch: “The communal administrator called a meeting in January to explain the referendum and why we had to vote yes. He sent the Imbonerakure out to force people to go to the meeting. We spent the entire day there; nobody could work. The Imbonerakure had clubs, and they would beat you if you did not attend.”

Gaston Sindimwo, Burundi’s first vice-president, was quoted in a January 18 Voice of America article as saying, “Political opponents who campaign for the no vote must be arrested because, for us, this is rebellious against the orders of the head of state.” Sindimwo also added, “If a member of the government is campaigning for the ‘yes’ vote, it is an error that will be corrected.”

The Burundian authorities should immediately and publicly order officials and Imbonerakure members to stop intimidating, beating, illegally detaining, and ill-treating people, Human Rights Watch said. The Burundian justice system should investigate and prosecute the crimes Human Rights Watch documented. The government should also publicly order the police to dismantle illegal roadblocks set up by the Imbonerakure.

In a 2016 letter to Human Rights Watch, Nancy-Ninette Mutoni, the executive secretary in charge of communication and information for the ruling party, wrote that Imbonerakure carry out political activities “calmly and serenely” and do not arrest people. “Those [Imbonerakure] who transgress are severely sanctioned first of all by the internal laws [of the ruling party] and if necessary, we will resort to penal laws,” she wrote.

Human Rights Watch shared the most recent findings with Mutoni but did not receive a response.

“The government has carried out widespread abuse of Burundians over the past three years, since President Nkurunziza announced his bid for a controversial third term, and now the government wants to force the population to prolong his rule even further,” Sawyer said. “The referendum campaign seems likely to bring even more crimes against the population.”

Descent into Lawlessness

Burundi has descended into lawlessness since April 2015, after Nkurunziza announced his bid for a disputed third term, despite the two-term limit set forth in the Arusha Accords. The political framework, signed in 2000, was the first of several power-sharing agreements intended to end the country’s civil war.

While Nkurunziza’s third term was disputed, the current constitution does not permit a fourth. The president and his party, the CNDD-FDD, called for a referendum to change the constitution to increase presidential terms to seven years, renewable only once. However, the clock on terms already served would be reset, enabling Nkurunziza to run for two new seven-year terms, in 2020 and 2027. The change could extend his rule until 2034.

A United Nations Commission of Inquiry has been investigating the serious crimes committed in the country since April 2015. In a report published in September 2017 at the end of its first year, the commission concluded that it has “reasonable grounds to believe that crimes against humanity have been committed and continue to be committed in Burundi since April 2015.” Following the report, the International Criminal Court opened its own investigation into Burundi.

Since 2015, political opponents in Burundi have been under increasing pressure and many say they fear for their lives. In 2016, Human Rights Watch published a report on how intelligence agents tortured and ill-treated scores of suspected government opponents at their headquarters and in secret locations across the country. In 2015 and 2016, Human Rights Watch also documented that armed opposition groups attacked security forces and ruling party members, including police and Imbonerakure.

Imbonerakure members have been involved in scores of human rights violations since at least 2009. In the period before the 2010 elections, which brought Nkurunziza his second-term victory amid numerous allegations of fraud, the ruling party used Imbonerakure members to intimidate and harass the political opposition, including through street fights with opposition parties’ youth wings.

Since the start of the current crisis in April 2015, members of the Imbonerakure have become increasingly powerful in some parts of the country, torturing, arresting, beating, and attacking FNL members and other suspected government opponents across the country. A May 2016 Human Rights Watch report documented that some rape and sexual violence survivors were able to identify Imbonerakure members who raped them. Some were targeted because their husbands or male relatives were opposition party members.

A 2017 Human Rights Watch report documents scores of cases across the country in which the Imbonerakure brutally killed, tortured, and severely beat people. Witnesses said some Imbonerakure are more powerful than the police, who do not intervene even when they know that Imbonerakure members are committing serious abuses.

Deaths Tied to the Referendum

Imbonerakure killed at least one man after he failed to show a receipt proving he had registered for the referendum, and another died possibly from beatings inflicted on him while he was detained for refusing to register.

On February 24, four Imbonerakure went to the home of Dismas Sinzinkayo, 36, a FNL member in Butaganzwa commune, Kayanza province. A witness told Human Rights Watch:

The Imbonerakure went to his house around 10:30 p.m. and asked for the receipt [showing he had registered]. He refused to show it to them. The Imbonerakure then pulled him out of his house and started to beat him. As they were beating him, they kept asking for the receipt. He said he had registered, but they did not care by then. He died on the spot.

Someone close to Sinzinkayo said that he had registered but may have been afraid to give the receipt to the Imbonerakure at night for fear that they would destroy it, giving them a pretext to arrest him later.

Several Kayanza residents said that the four Imbonerakure were arrested and held for three days, then released. A report by a Burundian human rights organization listed the names of the four Imbonerakure.

Contacted by telephone, the police commissioner of Kayanza, Méroe Ntunzwenimana, told Human Rights Watch that he was not aware of this case or Sinzinkayo’s existence. Ntunzwenimana laughed when Human Rights Watch explained that Sinzinkayo was killed by Imbonerakure and said it was not possible.

On February 14, local authorities in Cendajuru commune, Cankuzo province, took Simon Bizimana, 35, from his home because he had refused to register to vote. They took him to a meeting of local administrators where he was filmed explaining that he had not registered based on his religious principles.

Burundian media reported that local authorities beat Bizimana with iron rods after the meeting. While Human Rights Watch cannot confirm this, a witness at the local meeting said that a senior state official beat Bizimana before he was taken to jail. “She beat him with his Bible,” the witness said. “She yelled at him, ‘If this was a time of war, we would bury you alive!’” The official did not respond to a request for comment.

Someone close to Bizimana who was able to visit him once in detention said that he said his entire body hurt from the beatings he had received. On March 14, Bizimana was taken to the local hospital in a comatose state. Witnesses at the hospital told Human Rights Watch that he could not speak and that the police had to transport him in a wheelchair. Bizimana died there on March 18.

On March 19, the Burundian police tweeted a claim that they had released him in good health on March 14, accompanied by a photo of a medical report claiming that Bizimana died of malaria. However, a hospital official told Human Rights Watch that Bizimana tested negative for malaria and was “already close to death” when police brought him there.

Beatings, Ill-Treatment, Arbitrary Arrests

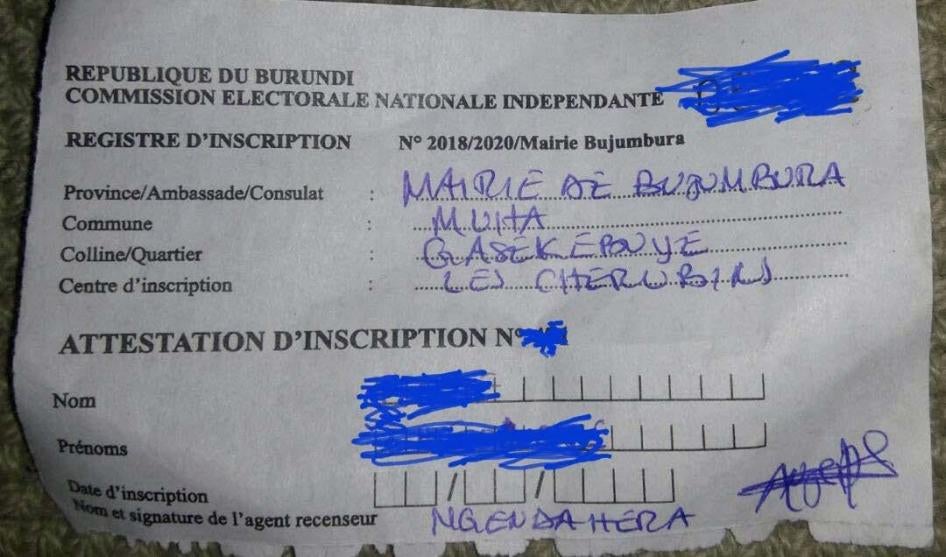

Human Rights Watch has documented 17 cases of arrests, beatings, and other forms of ill-treatment by local authorities, police, and members of the Imbonerakure against people suspected of either not registering for the referendum or planning to vote no. The Imbonerakure have no legal authority to detain people. The registration took place from February 8 to 17.

A resident of Moya hill in Karusi province’s Buhiga commune described a beating he witnessed at a roadblock manned by the Imbonerakure in late January:

The zone chief and the Imbonerakure had set up a barrier to check the receipts to see if people had registered. This was just at the end of the registration period. I saw them ask a driver from Muyinga for his receipt, but he did not have it. The Imbonerakure had clubs and they pulled him out of the car and beat him… There were two Imbonerakure. As they were beating him, the Imbonerakure yelled, “If you do not register, it means that you are against the referendum!” This happened near my home and after I saw that, I knew that I could not travel without my receipt.

A businessman from Buhiga commune, Karusi province, said Imbonerakure beat him on February 10 at a roadblock. He had his receipt with him, but he did not show it, insisting he was a Burundian and did not have to prove anything. “There were many of them and some had metal cables,” he said. “They started to hit me, and I fell off my bike. They continued to beat me on the ground and yelled, ‘We will fight all opponents!’ This is happening all over; everyone is scared of the Imbonerakure.”

A resident of Muyinga said an Imbonerakure member beat him on February 27 after he overheard the resident telling a woman that he was going to vote no. “There is no point in voting,” he had said, “but I will vote against it.” He explained what happened next:

An Imbonerakure heard me and came and slapped me twice in the face. He then took me to the jail. I spent three days there. When I asked the judicial police officer to explain why I was detained, he said, “You are telling people to vote against the referendum, so this issue is not for my level. I will get an order from higher up as to what to do with you.” They let me go after three days, and I returned to university [in another province]. Now I am scared to return home, but I have to vote. I have no choice.

A member of the FNL said he was suspected of telling people in his area to vote no. Imbonerakure arrested him on February 2 in Kirundo commune, Kirundo province:

They came to the house at 7 a.m. and said they had been sent by the local chief. There were five Imbonerakure, and they started to beat me straight away. They beat me in front of my wife and kids. As they beat me, they said, “We were told to come for you because you are telling people to vote no!” But it was not true…. I was taken to jail and the police told me I would have to wait there until I was charged. I did not have a lawyer. In the end, I was released without charge. They just told me to leave… When I got out of jail the authorities and the Imbonerakure were launching their own campaign and telling people to vote yes on the referendum… I am scared I will be arrested again or killed during the electoral period.

The man was released on February 20, 18 days after his arrest.

Two FNL members were also detained in Kirundo on January 24. Human Rights Watch spoke separately with both men. One said:

We were in a bar talking about the referendum. We both agreed that we were going to vote against changing the constitution. An Imbonerakure heard us, and he called his friends… Six Imbonerakure came back and beat us with sticks and then took us to the jail. As they were beating us, they asked who we had instructed to vote no. I said, “No, it is just our opinion; we do not want to change the constitution.” We spent two weeks in jail. We were never charged, but we had to pay a fee of 20,000 FBU [approximately US$11] each and then we were released. When we were released a local authority said, “If I hear again that you will vote no, we will make you disappear.”

Another FNL member from Gasorwe commune, Muyinga province, said:

It is known that I am a member of the FNL. I was attacked in a bar by the Imbonerakure on January 20. I ran to the police station for protection, and they agreed to put me in a cell. But the Imbonerakure followed me to the police station and said that I had been telling people to vote no on the referendum, but this was a lie. The administrator gave the order to keep me detained. Before they sent me to the central prison, the prosecutor came to see me and said, “If you lead a campaign telling people to vote no on the referendum, then it is an attack against the security of the state.”

The man was held for two months and released on March 20.

Human Rights Watch spoke individually with three FNL members who said they had been detained on suspicion of campaigning against the referendum on March 16, the day they were provisionally released from prison in Muyinga province after almost two months in detention. Each was fined 50,000 FBU [approximately US$28]. One said:

In January I was speaking with a woman who lived near me. I told her that I was going to vote against changing the constitution. That night, around 7:30 p.m., the Imbonerakure came. There were many of them; they were with their leader and a local authority. They wanted me to step outside, but I refused to leave the house to talk to them because I knew they would beat me. They called the police to come arrest me. I was taken to the jail and the next day the judicial police officer said that I had “launched a campaign against the referendum.” I said that I had done no such thing, but they made me sign documents that I was not allowed to read, and then they took me to prison.

Some of those arrested have no ties to political parties. Jean Claude Niyongere, a doctor from Karusi province, was arrested on February 22 because of a message he sent over WhatsApp. The message includes a photoshopped photo of the ruling party’s secretary general, Évariste Ndayishimiye, wearing a hat that reads “Tora Oya” (“Vote No” in Kirundi). Niyongere was released provisionally in mid-March, but he has been charged with serious crimes, including endangering state security. If found guilty, he could face up to 15 years in prison and a fine of 600,000 FBU [approximately US$340].