Diagnosed with leukemia when he was 5, Fadi (not his real name) was still experiencing side-effects from his treatment when Human Rights Watch researcher Bill Van Esveld went to speak to him and his mum about the abuse he’d suffered in his old school in Lebanon’s Bekaa governorate.

Sitting on a sofa their living room, Fadi’s mum, “Rasha,” explained to Van Esveld that Fadi’s medication and treatment made it hard for her son to concentrate. But instead of helping him, the school staff berated him, hurling verbal insults and physically abusing the young boy. One teacher would pull his hair, call him an idiot or a “donkey,” and force him to stand outside. Rasha complained to the school director – who Fadi said also pulled his hair – but she told Rasha her son should be in an institution for children with disabilities.

Fadi has a serious medical condition, not a disability. But the director was open about wanting to kick him out. In Lebanon, children with disabilities who should be accommodated in schools are instead often sent to institutions that aren’t even mandated to provide an education.

“He gets severe headaches, and when he got them the director would call me and say, ‘don’t bring him here anymore,’” she told Van Esveld. According to Fadi, he had also missed an exam because he fell due to his illness and broke his jaw, which he said annoyed the principal.

Physical abuse of students is widespread in Lebanon, despite it being illegal since the 1970s. In a new report, “I Don’t Want My Child to Be Beaten,” Human Rights Watch researchers spoke to 51 children, as well as parents, teachers, and education campaigners about what is going on in the country’s schools. What they found amounted to a human rights abuse.

Fadi had originally been in a private school in the Baalbek-Hermel governorate, but when the family moved to a different town in the Bekaa region for work, his parents couldn’t afford to pay for education. He entered the public system when he was nine years old.

It was at this public school that Rasha noticed the teaching staff did not behave decently towards her son and failed to make accommodations to help him learn. When Rasha went to the school to complain, which she did at least four times, she was told that her son couldn’t be given any “special treatment.” Far from special treatment, all she was asking was that they stop emotionally and physically abusing her sick child.

Fadi became the focus of one teacher in particular, who would call him a “donkey” when his headaches made it difficult for him to concentrate, and who forced Fadi to stand outside in the cold as punishment.

For Rasha, who is also looking after Fadi’s two siblings, the emotional distress compounded the worry surrounding Fadi’s health. Every day, she saw her son come home from school miserable and crying on top of everything else he was dealing with.

On the outside, she tried to stay happy and positive, supporting her son and trying to keep him calm and help him through his illness, but inside she was in shock at how he was being treated and how little the school seemed to care.

Rasha made coffee as she spoke about her son and discussed how the frustration she felt led her to help Fadi write a public post on Facebook. The family is Palestinian and Rasha’s concerns about the prejudice Palestinians can face in Lebanon meant she only complained publicly after she exhausted all her other options. After his parents separated, Fadi was even more reliant on Rasha. She became his entire support network.

“There was no one else for me to complain to,” she said. Fadi’s teacher had even pulled Fadi’s hair in front of his mother when she went to the school to complain, as if the abuse had become an unthinking part of the teacher’s routine.

After the posts got some attention, the minister of education was interviewed by a local television station, and suggested on-air that the family could follow up on Fadi’s case with ministry officials in Beirut. Another news segment recorded the school principal saying Fadi should be in an institution and that his appearance, as a result of his chemotherapy, upset the other children. Despite all this, Rasha says, no one from the ministry followed up with her, and the abuse continued.

“I was trying so hard to keep him emotionally strong, and not upset, because that’s the most important thing when you have cancer. And he’d come home upset every single day. He hated going to school,” she said.

In 2018, Lebanon launched a child protection policy which specifically includes a provision banning teachers from harming pupils. But similar prohibitions have been in place for decades. The laws are rarely enforced and teachers breaking them often don’t face any consequences.

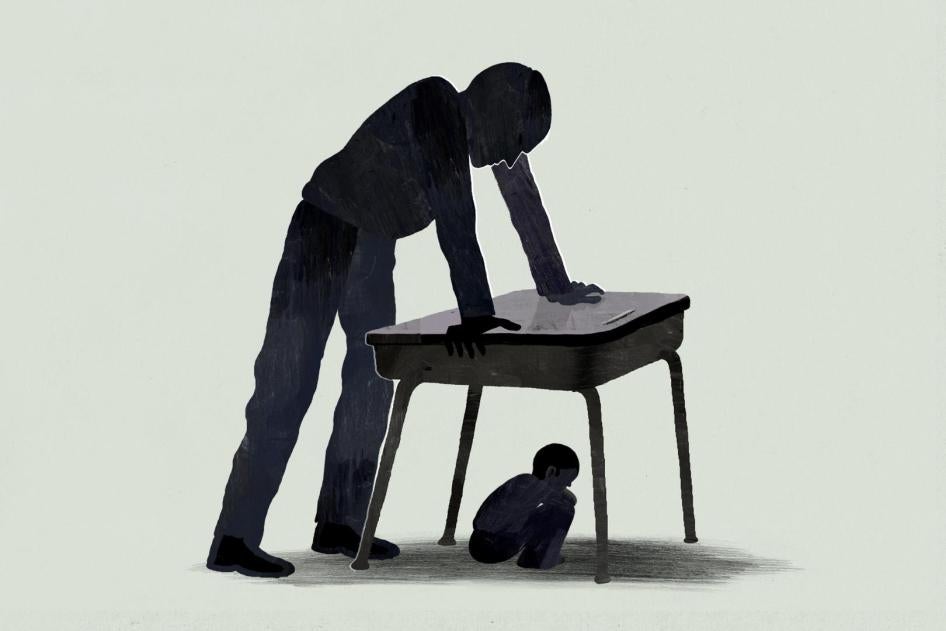

Parents told Human Rights Watch about their kids being beaten with sticks and other objects, hit in the face, and dragged from under desks where they were trying to escape the beating, only to be hit again.

One ten-year-old boy was yanked upwards by his nose twice, breaking it, and his mother only found out when he returned home covered in blood. A girl was accused of cheating by a teacher who suspected her of using a calculator in math class. She was beaten round the face so harshly it was still bright red and swollen when she went home two hours later. Some parents go straight to the police when they see the state of their children, and told Human Rights Watch about their frustration when the police failed to take any action.

The problem is even more acute for the children of Syrian refugees – 210,000 of whom attend public schools in Lebanon – as their families are often too terrified to complain because of their tenuous status in the county. In one case, the abuse of Syrian children in a school got so bad the entire community pulled their kids out of class and refused to send them back until the issues – like refusing to give them access to the bathroom and beating them – were dealt with.

Fortunately for Fadi, a choice did eventually present itself. Rasha did some research and found a private school offering scholarships to low-income families, and he was able to switch last year. Fadil now enjoys going to school again and she can begin looking for work knowing he is happy.

Fadi still has rough days, like on the day he met Van Esveld, but at least when he can go to school, he enjoys it.

“Now, they even carry his backpack for him,” said his mum.