Summary

“We are always scared of tomorrow because the school could say we need to remove him.”

—Huda, the mother of Wael, a 10-year-old boy with autism, Beirut, April 13, 2017

Under the law, all Lebanese children should have access to education free from discrimination. Lebanon’s Law 220 of 2000 grants persons with disabilities the right to education, health, and other basic rights. It set up a committee dedicated to optimizing conditions for children registered as having a disability to participate in all classes and tests.

In reality, the educational path of children with disabilities in Lebanon is strewn with logistical, social, and economic pitfalls that mean they often face a compromised school experience—if they can enroll at all.

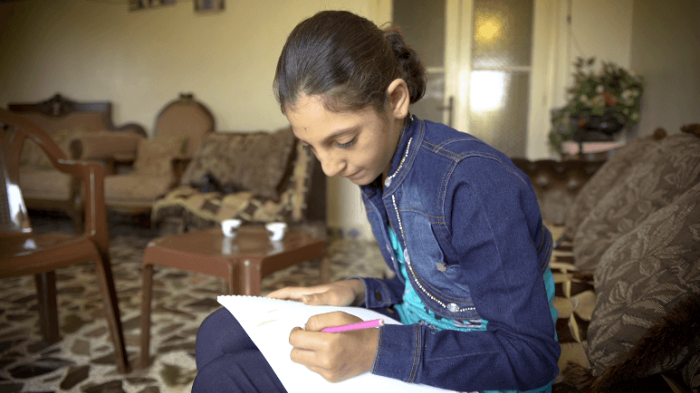

Basmah, a 9-year-old girl with Down Syndrome, puts on her own backpack every day as she gets in the car to accompany her siblings to school—but despite her enthusiasm, no school has accepted her because of her disability. Human Rights Watch interviewed 33 children or their families, who said they were excluded from public school in Lebanon on account of disability, in what amounts to discrimination against them. Of these, 23 school-age children with disabilities in Beirut and its suburbs, Hermel, Akkar, Nabatieh, and the Chouf districts, were not enrolled in any educational program.

In the cases Human Rights Watch investigated, most families said children with disabilities were excluded from public schools due to discriminatory admission policies, lack of reasonable accommodations, a shortage of sufficiently trained staff, lack of inclusive curricula (including no individualized education programs), and discriminatory fees and expenses that further marginalize children with disabilities from poor families.

There is no clear data on the total number of children with disabilities in Lebanon or on how many children with disabilities are in school. According to Rights and Access, the government agency charged with registering persons with disabilities, there are currently 8,558 children registered with a disability aged between 5 and 14 (the age of compulsory education in Lebanon). Of these, 3,806 are in government-funded institutions, with some others spread among public and private schools. But many of those registered do not attend any type of educational facility. Furthermore, these figures are low, given that the United Nations children’s agency (UNICEF), the World Health Organization (WHO), and the World Bank estimate that at least 5 percent of children below the age of 14 have a disability. Based on this statistic, a conservative estimate is that at least 45,000 children ages 5 to 14 in Lebanon have a disability. This discrepancy raises concerns that tens of thousands of Lebanese children with disabilities are not registered as such and many of these may not have access to education.

According to the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), which Lebanon ratified in 1991, children with disabilities have the right to education, training, health care, and rehabilitative services. The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, which Lebanon has signed but not ratified, promotes “the goal of full inclusion” while considering “the best interests of the child.” Law 220 mirrors this principle in requiring the best interest of the learner when it comes to inclusive versus special education.

As detailed by the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, inclusive education has been acknowledged as the most appropriate means for governments to guarantee universality and nondiscrimination in the right to education. Inclusive education is the practice of educating students with disabilities in mainstream schools with the provision of supplementary aids and services where necessary to allow children to achieve their full potential. It involves the recognition of a need to transform the cultures, policies, and practices in schools to accommodate the differing needs of individual students and an obligation to remove barriers that impede that possibility.

The affirmation of the right to inclusive education is part of an international shift from a “medical model” of viewing disability to a “social model,” which recognizes disability as an interaction between individuals and their environment, with an emphasis on identifying and removing discriminatory barriers and attitudes in the environment. In Lebanon, however, authorities still seem to generally treat disability as a defect that needs to be fixed.

This report focuses on the barriers to quality and inclusive education for Lebanese children with disabilities who are at the age of compulsory education in Lebanon. It also assesses the segregated system of Ministry of Social Affairs (MOSA)-funded institutions, which is supposed to be the educational resource for children with disabilities kept out of school.

Although Lebanese law explicitly prohibits schools from discriminating against children with disabilities in enrollment decisions, admission to public and private schools continues to depend on the discretion of teachers and school directors, which leads to the exclusion of many children. When Huda tried to enroll her son Wael, a 10-year-old boy with autism, she went to many schools in the Beirut area. But she said one after another, they turned her away with explanations that included: “We don’t take handicap [sic]” and “We cannot accept your son, because the other parents might not approve.”

Most public and private schools that Human Rights Watch researched lack reasonable and appropriate accommodations that ensure a learning environment in which all children can participate fully. In Akkar, for example, Jad, a 9-year-old, music-loving boy who uses a wheelchair, attends a private school where the bathrooms are not accessible. As a result, Jad is forced to wear diapers, which his mother must come to school once a day to change. One of the few public schools in Jad’s district that accommodates children with disabilities has a wheelchair-accessible bathroom located on the second floor, but that floor is not wheelchair-accessible.

A 2009 survey conducted by the Lebanese Physical Handicap Union revealed that only 5 of 997 public schools observed met all of Lebanon’s physical accessibility standards for public buildings.

The education of children with disabilities is also hampered by a lack of reasonable accommodations, including basic physical accessibility in buildings; a lack of adequately trained teachers; a lack of an individualized approach to children’s education; and discriminatory fees and other expenses such as transportation.

Ahmed, a 5-year-old boy with a speech disability, attends a public school in Akkar. When he started his teachers could not understand him. In order for him to remain at the school, the school required his family to take Ahmed for speech therapy, and cover the costs, including transportation. The school did nothing to provide assistance or accommodations to Ahmed and his family. Possible classroom accommodations could include written assignments or written responses that someone else could read aloud.

A lack of community-based services and support means that many children with physical, sensory, or intellectual disabilities must travel long distances—spending up to six hours a day in a car—or sleep in residential institutions in order to access any educational, health care, or other support services, such as early childhood education.

Imad, a 4-year-old who has a hearing disability, was denied admission to a school by local school administrators in Hermel, a district in northeastern Lebanon, because he uses a hearing aid. His only educational options are either to enroll at a residential institution in Beirut, about 150 kilometers away, or to make daily trips to a school in the nearest large town, Baalbek—amounting to a 10-hour school day at a cost of US$100 per month. Both options were out of the question for Imad’s mother. “I have three other children to take care of,” she explained. With no alternative, Imad will stay out of school for the foreseeable future.

Under Lebanese law, specialized segregated institutions funded by MOSA—some of which are residential—are supposed to serve as the educational alternative to school exclusively for children with disabilities, yet the educational resources at these institutions are often of poor quality. Most of the specialized institutions are not even classified as schools by the Ministry of Education and Higher Education (MEHE). Lack of monitoring for quality education, a reliance on poor evaluation mechanisms, and a dearth of appropriate resources raises serious concerns about whether these institutions fulfill children’s right to education. “Most of them are just day care centers—nothing more,” a disability rights expert told Human Rights Watch.

Conditions in some of the institutions are problematic. At two institutions that Human Rights Watch visited, there was no separation between children and unrelated adult residents. At one institution, boys and men ages 5 to 50 slept in the same dormitory-style bedrooms. At another, the ages of residents in the same room ranged from 8 to 30.

The obstacles that children with disabilities face are not unique to Lebanon. Approximately 90 percent of children with disabilities in low income and lower-middle income countries do not go to school. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) estimates that children with disabilities represent more than one-third of the 121 million children at the primary and lower secondary level who are out of school worldwide.

In recent years, the Lebanese government has taken steps in the right direction. MEHE has made some efforts to include children with learning disabilities in public schools, and is planning a pilot program for 2018 to have 30 inclusive public schools around the country that will accept children with learning disabilities and 6 that will accept children with visual, hearing, physical, and moderate intellectual disabilities. The right to education applies to all children with disabilities. No matter how high their support needs are, every child, without exception, has the right to an education.

Private nongovernmental organizations and UNICEF have tried to make public schools accessible through building modifications that can help accommodate children with physical disabilities. Other private nongovernmental organizations pay for trained teachers and materials that allow children with visual disabilities to be integrated into the classroom. Some private schools have also made significant efforts to include children with disabilities in classrooms, including by providing them with a shadow teacher and additional supportive material, although usually at a financial cost to the child’s family.

Inclusive education benefits all students, not only students with disabilities. A system that meets the diverse needs of all students benefits all learners and is a means to achieve high-quality education. Inclusive education can promote a more inclusive society. As Khalil Zahri, the school director of Zebdine Public School put it, “the classes with children with disabilities are the most successful.”

Inclusive education stands in sharp contrast to the special education model, in which children with disabilities are taught in segregated schools outside the mainstream, in special programs and institutions and with special teachers. In this system, children with and without disabilities have very little interaction, which can lead to greater marginalization within the community, “a situation that persons with disability face generally, thus entrenching discrimination.”

While an inclusive education system cannot be achieved overnight, Lebanon should introduce new legislation to bring its national laws and practices in line with international law and standards. At the same time the Lebanese government should implement and enforce existing disability rights legislation, such as Law 220 of 2000, passed 18 years ago but never fully implemented. While Lebanon should dedicate more funds to make schools inclusive of all children, inclusive education does not have to be costly. A global World Bank study from 2005 found that even where modifications are necessary to ensure that buildings are physically accessible to people with disabilities, making the necessary adjustments usually costs only 1 percent of the overall building cost. A key step toward inclusion is to train teachers on inclusive education methods, which can be integrated into existing training.

While Lebanon has a history of laws that promote the rights of people with disabilities and recently has made some progress in providing education for children with disabilities, significant work is needed to implement those laws and bring Lebanon into line with international standards. By taking specific steps to protect the rights of children with disabilities and ensuring they have equal access to quality education in inclusive schools, the Lebanese government and its international partners could radically enhance the quality of life for many children with disabilities in Lebanon.

Recommendations

To Parliament

- Amend Law 220 or pass new legislation that would require schools to take all necessary steps to accommodate children with disabilities.

To the Ministry of Education and Higher Education (MEHE)

- Implement inclusive education in such a way as to achieve maximum inclusion of children with disabilities, including children with high support needs, in mainstream public and private schools. The Ministry should create a focal point, or directorate, with the responsibility to ensure inclusive education.

- Develop and implement a longer-term inclusive education plan that clarifies the concept of inclusive education in line with international standards and outlines steps to include all children with disabilities, including those with high support needs, into mainstream schools.

- Take necessary measures to provide individualized support to students with disabilities who attend public schools.

- Add a disability-focused component to the Back-to-School information dissemination initiative detailed in the Reaching All Children With Education II (2017-2021) documents.

- Hire personnel with required expertise and experience to ensure the general educational system is inclusive and capable of providing quality education to students with disabilities.

- Develop guidelines and standards on inclusive classrooms for teachers and school administrators and develop procedures to ensure that they are met. Allocate adequate funding for inclusive education for children with disabilities, including targeted funding, in budgets and requests for development assistance.

- Adapt school curricula for inclusive education. Develop a curriculum and assessment systems suitable for all learners, including children with intellectual or developmental disabilities.

- Provide adapted academic material for children learning in sign language and Braille.

- As per the law, ensure all official examinations accommodate the needs of all children with disabilities.

- Ensure every school has a team dedicated to developing individualized education plans and to discussing accommodations and modifications when needed to meet a student’s needs.

- Lay out standards and conditions for private sector schools for the inclusion of students with disabilities and supervise the application of such standards and conditions.

- Revise the teacher training materials to reflect inclusive education methods and increase awareness about children with disabilities.

- Train all teachers and school administrators on inclusive education methods and practical skills, including on the use of appropriate languages, modes, and means of communications, such as basic sign language.

- Provide continuous training, support, and mentoring of teachers and assistants, including through resource centers and professional exchange.

- Train teachers and school administrators on how to avoid and address bullying, teasing, or other discriminatory and degrading treatment of children with disabilities in the classroom, transportation, and the rest of the school.

- Provide training for school directors on how to maintain an inclusive school.

- Train and support parents of children with disabilities, including through regular parents’ meetings to exchange information and provide peer support.

- Develop or strengthen early identification and intervention programs consistent with the inclusive approach to education and take steps to ensure children with disabilities have access to early childhood development programs.

- Strengthen and regulate monitoring of schools, including special schools, to ensure that children have access to quality education.

- Involve children with disabilities and their parents or family members in consultations and decision-making and monitoring processes. Develop strategies to increase community and family participation.

To the Ministry of Social Affairs (MOSA)

- Allocate sufficient resources for the development and sustainability of a range of services and support for children with disabilities and their families so that they can attend schools on an equal basis with other children. Services should include assistance so that families of children with disabilities can look after their children and have full access to assistive devices, transportation, healthcare, and other necessary services. The services and support need to take into account those children who require intensive support or may be at risk of remaining in institutions indefinitely.

- Ensure children with disabilities, their families, and disabled persons organizations are included in the development of services.

- Create and implement a deinstitutionalization policy and a time-bound action plan for deinstitutionalization, based on the values of equality, independence, and inclusion for persons with disabilities.

- Make sure that necessary services and support in communities focusing on inclusion of persons with disabilities is an important part of the deinstitutionalization plan and that persons with disabilities, disabled people’s organizations, and organizations working on deinstitutionalization are invited to participate in the formation of this plan.

- Redefine the role of MOSA-funded institutions, including residential institutions, from places responsible for the education of children with disabilities to, instead, centers that provide extracurricular support and other necessary support services to meet educational and developmental needs of children with disabilities, including speech therapy, physical therapy, and educational support for children with disabilities when necessary.

- When necessary, seek out the experiences of other countries that have fully undergone deinstitutionalization.

- Recognize institutionalization based on disability as a form of discrimination and that institutionalization against the consent of older individuals might be a form of detention.

- Develop procedures and tools to more proactively collect data on persons with disabilities in communities and provide more incentives for persons to register for a disability card.

- Create standard procedures, policies, and a unified database of services and resources at the Ministry.

- Publicize what resources (MOSA supported or private) are available for persons with disabilities in each region. Conduct needs assessments to determine where there are gaps in services.

- Together with the Ministry of Education, carry out awareness-raising campaigns on the right to education, nondiscrimination, and other rights of persons with disabilities, targeting the public at large, teachers, school administrators, and parents.

- Launch an information campaign to inform parents about what resources are available to their children.

- Provide accessible and affordable transportation to enable children with disabilities to access schools, especially in rural areas where distances to schools may be greater.

- Work together with other relevant ministries to ensure public transportation is free from violence against all children.

- Encourage teachers and classroom assistants trained on inclusive education and with practical skills to include and support children with disabilities in mainstream public and private schools to live and work rural areas that are under-served.

- Make funds available for public schools or private schools, if the family opts to send their child to a public or private school rather than a MOSA-funded institution.

- Allow parents to receive financial support that would otherwise be distributed to residential institutions, if a family wants and can support a child with disabilities in the home.

- Strengthen existing or establish new channels for people with disabilities to lodge complaints on laws that are not implemented or enforced.

To Multilateral and Bilateral Donors, UN agencies, and International NGOs

- Include children with disabilities and inclusive education in existing and future programs and policies, especially teacher training.

- Strengthen the capacity of the Lebanese government to implement an inclusive education approach through the development of stronger planning, implementation, and monitoring and evaluation processes and by encouraging greater collaboration among relevant ministries.

- Ensure sufficient funding for inclusive education. Consider funding the government, organizations for people with disabilities and NGOs for programs to support children with disabilities and realize their rights, particularly the right to education.

- Strengthen data collection on children with disabilities.

- Help the Ministry of Education and Higher Education achieve inclusive education by developing, distributing, and raising awareness of appropriate and easy-to-use inclusive education materials and encouraging public discussion.

To the Government

- Ratify the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

Methodology

This report is based on research conducted by Human Rights Watch researchers between January and June 2017 in the city of Beirut and its suburbs, Hermel, Akkar, Nabatieh, and the Chouf districts in Lebanon. Of the twenty-six districts spread throughout Lebanon’s eight governorates, Human Rights Watch selected these five districts to document the range of barriers children with disabilities face in areas that differ in population density, socioeconomic levels, religious affiliation, level of urbanization, and distance from major health care service centers.

Evidence used in this report is based on the experiences of 105 children and young adults with disabilities shared by them or their families. Human Rights Watch visited and conducted interviews in 6 public schools, 5 private educational service-providing centers, and 17 Ministry of Social Affairs (MOSA) funded institutions. We also interviewed 30 disability rights and education experts and advocates and 13 government officials.

In Akkar, Hermel, Nabatieh, and the Chouf, Human Rights Watch visited 9 of the 10 MOSA-funded institutions that offer education for children with disabilities in those regions, and spoke with 63 staff and in some cases students and their parents there.

Due to the size of Beirut and its suburbs, researchers consulted with experts in the disability rights field to select a representative range of educational opportunities to visit. These institutions included Dar al-Aytam al-Islamiya, Blessed, Mabarrat’s al-Hadi, and al-Zawark.

Aside from these districts, researchers visited additional institutions in Baalbek, Saida, and two in Zahle. In total, Human Rights Watch visited 17 institutions, 7 of which were residential.

Researchers also visited six private facilities that fill some gaps in government services in these areas, including speech therapists, physical therapists, physiotherapists, psychologists, after-school tutoring, and in-home services.

In all cases, Human Rights Watch informed interviewees of the purpose of the interview, that they would receive no personal service or benefit, and that the interviews were completely voluntary. Participants gave informed consent to participate and informed consent for their story to be shared.

Interviews with children were conducted in Arabic with the assistance of an interpreter, fluent in Arabic and English. Interviews with parents, institution staff, government officials, and representatives of Lebanese nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) were largely conducted in English or Arabic with the assistance of an interpreter. In two cases, a teacher from an institution used sign language to facilitate communication between researchers and children with a hearing disability at the institution.

Unless otherwise noted, we have used pseudonyms for all children, young people, and their families in order to protect their privacy. In some cases, we have withheld other details, such as the name of the institution where an interview took place. We have also withheld names and other details about some institutional staff to protect them from possible reprisal.

Children with disabilities and their families who were interviewed were selected through outreach via MOSA-funded institutions, services providers, community leaders, and NGOs.

This report focuses on Lebanese children, and may not account for additional barriers faced by Syrian or Palestinian refugee children with disabilities.

I. Background

Globally, around 90 percent of children with disabilities in low income and lower-middle income countries do not go to school.[1] The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) estimates that children with disabilities represent more than one-third of the 121 million children at the primary and lower-secondary level who are out of school worldwide.[2] There is no clear data on the total number of children with disabilities in Lebanon or on how many are out of school. In fact, data on both the size of the overall school-age population in Lebanon and age-specific prevalence of disability within populations throughout the world is so scarce that only general estimates of the total number of children with disabilities are available. According to the Lebanese government’s figures, there are 8,558 compulsory school-age children registered with a disability in the country.[3] But based on global estimates by international agencies finding that at least 5 percent of children below the age of 14 have a disability, and that 17.4 percent of Lebanese nationals are between 5 and 14 years old, the reality may be that more than 45,000 Lebanese children of compulsory school age have a disability.[4]

Global statistics from 2013 showed that of the 10 percent of all children with disabilities who were in school, only half completed their primary education, with many leaving after only a few months or years, because they were gaining little from the experience.[5] Children with disabilities who attended school were more likely to face exclusion in the classroom and to drop out.[6]

Lebanese Education System

The education system in Lebanon is overseen by the Ministry of Education and Higher Education (MEHE). Education in Lebanon is split into three phases: pre-school, basic, and secondary.[7]

The basic phase, for children ages 5-14, is compulsory and is divided between grades 1-3 (cycle one), grades 4-6 (cycle two), and grades 7-9 (cycle three). At the culmination of cycle three, students take a national exam called the Brevet. The Brevet score helps to determine a student’s placement in further education and whether they will continue on an academic or technical track for secondary school, which comprises grades 10-12. After grade 12, students take the official Lebanese baccalaureate exams, which are required for admission to most universities in the country.[8]

Academic establishments are broadly divided into public, semi-private, and private schools, and are accredited by MEHE. There are 1,279 public schools in Lebanon, which MEHE funds and supervises.[9]

Law 220 guarantees equal opportunities within all public and private educational or learning establishments for persons with disabilities, and stipulates that MEHE shall cover the educational and occupational costs of specialized institutions when called for by the Ministry of Social Affairs (MOSA).[10]

MOSA-Supported Institutions

Article 61 of Lebanese Law 220/2000 stipulates that MEHE is charged with financing special schools and education for children with disabilities.[11] However, MEHE representatives told Human Rights Watch that children with physical and intellectual disabilities are not part of the MEHE school system.[12] Although Human Rights Watch found that some children with disabilities attended public schools, the vast majority of children with a disability who were receiving any educational support from the government were securing it is through the MOSA-funded institutions.

Through contracts with private organizations, MOSA provides funding for a limited number of children to attend one of the 103 segregated institutions it supports across the country. Many children with disabilities are not even able to attend a MOSA-funded institution due to limited capacity.[13]

There is little uniformity among these different institutions, which may be religiously affiliated, politically affiliated, or both. Some of the institutions offer residential spots. Institutions that Human Rights Watch researched vary in size from 32 residents to 600, and in the ages of their residents. One institution Human Rights Watch researched accommodated children from 1 to 12 years old; another accommodated residents from 4 to 80 years old.

While the characteristics of these institutions vary greatly, their contracts with MOSA are largely standardized. Where the contracts do vary is in the number of children with certain disabilities that the institution will accept, the type of services the institution offers, and how many residential or non-residential spots an institution can have. MOSA provides funding according to a daily rate, which varies based on the factors mentioned above, but which has not changed since 2012. These contracts are not determined by the needs in particular regions, but rather they are often the result of a negotiation between institutions and MOSA.[14]

While some of these institutions provide academic services, there is no mechanism that monitors for quality of education at institutions. According to interviews with MEHE, MOSA, and institutions, no institutions are supervised or monitored by MEHE. Only 1 of the 17 that Human Rights Watch visited was registered with MEHE as an official school. MOSA conducts monitoring visits to check the quality of the facilities, but not their educational standards.

Inclusive Education Model

In an inclusive education system, all students learn in the same schools in their communities regardless of whether they are “disabled and non-disabled, girls and boys, children from majority and minority ethnic groups, refugees, children with health problems, working children, etc.”[15] Inclusivity requires that the content and methods of education are modified and that the system provides support, as needed, to meet the diverse needs of all learners.[16] Inclusive education therefore is not only relevant for the education of students with disabilities, but should benefit all children and be “central to the achievement of high-quality education for all learners and the development of more inclusive societies.”[17] Studies have shown that students with disabilities achieve better academic results in an inclusive environment when given adequate support than they do in segregated, “special education” settings.[18]

Inclusive education focuses on removing the barriers within the education system itself that exclude children with special educational needs and cause them to have negative experiences within school.[19] It requires teachers and classrooms to adapt, rather than for the child to change. Support services should be brought to the child, rather than relocating the child to the support services.[20] In an inclusive classroom, children with disabilities have individual education programs to guide the teacher, parents, and student on how to achieve the best educational outcomes for the child.

Inclusive education is distinct from two other approaches to educating people with disabilities.[21] One is segregation, where children with disabilities are placed in educational institutions that are separate from the mainstream education system. Another is integration, where children are placed in mainstream schools, but only if they can adapt to these schools and meet their demands. Unlike inclusive education, integration tends to regard the child with a disability rather than the school as the one who needs to change.[22] Inclusion focuses on identifying and removing the barriers to learning and changing practices in schools to accommodate the diverse learning needs of individual students.

Specialized classes within mainstream schools may be beneficial for some students with disabilities to complement or facilitate their participation in regular classes, such as to provide Braille training or physiotherapy.[23]

The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) requires states parties to take measures to ensure the full and equal participation of children with disabilities in education, including:

(a) Facilitating the learning of Braille, alternative script, augmentative and alternative modes, means and formats of communication and orientation and mobility skills, and facilitating peer support and mentoring;

(b) Facilitating the learning of sign language and the promotion of the linguistic identity of the deaf community;

(c) Ensuring that the education of persons, and in particular children, who are blind, deaf or deafblind, is delivered in the most appropriate languages and modes and means of communication for the individual, and in environments which maximize academic and social development.[24]

Inclusive education stands in sharp contrast to the special or separate education model, in which children with disabilities are taught in segregated schools outside the mainstream, in special programs and institutions and with special teachers.[25] In this system, children with and without disabilities have very little interaction, which can lead to greater marginalization within the community, “a situation that persons with disability face generally, thus entrenching discrimination.”[26]

Disability Laws and Education

Lebanon still adheres to an outdated “medical model” that regards disability as an impairment that needs to be “treated,” “cured,” “fixed,” or at least rehabilitated.[27] In contrast, the United Nations adopted a rights-based approach, enshrined in the CRPD, which views disability as a result of the interaction between persons with physical, sensory, intellectual, or psychosocial impairments and attitudinal, communication, and environmental barriers that hamper their full participation in society.[28] Article 19, a human rights organization, points to this difference in approach as one of the reasons Lebanon has a significantly lower official recorded prevalence of disability than the global average: 2 percent, versus the World Bank and World Health Organization statistic that 15 percent of the world’s population has a disability.[29]

Lebanon has signed and ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child, which obligates states to make primary education compulsory and free to all without discrimination.[30] It specifies that states should ensure that children with disabilities have effective access to and receive education, training, health care services, and rehabilitative services.[31] Lebanon has also signed, but not ratified, the CRPD, which promotes “the goal of full inclusion” at all levels of education, and obliges State parties to ensure children with disabilities have access to inclusive education, and that they are able to access education on an equal basis with others in their communities.[32] Inclusive education involves children with disabilities studying in their community schools with reasonable support for academic and other achievement.

In Lebanon, the National Commission for Disability Affairs was established in 1993 and was restructured by Law 220 in 2000 to be composed of four MOSA officials, two disability experts appointed by the Minister of Social Affairs, four elected representatives of disabled people’s organizations, four elected persons representing institutions, and four elected persons with disabilities.[33] In 1994, the commission created an implementing body—Rights and Access—charged with defining and ensuring the rights of persons with disabilities and facilitating access to these rights.[34]

Rights and Access developed a card identification system for persons with disabilities in Lebanon. A person may obtain such a card by going to one of seven centers around the country, operated by MOSA.[35] Lebanon recognizes 165 disabilities, based on the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Impairments, Disabilities and Handicaps from 1980.[36] Lebanon still uses this publication even though in 2001, the World Health Organization replaced this diagnostic tool with the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health.[37] Persons who receive a disability card are legally entitled to a range of benefits, such as life insurance, tax benefits, and assistance paying for healthcare, educational, and rehabilitative services.[38] However, instead of a right to inclusive quality education on an equal basis with other children, educational services include specialized education, learning, or occupational training until the age of at least 21.[39]

Law 220/2000

In 2000, the Lebanese parliament passed Law 220 on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, guaranteeing “adequate opportunities for the education and learning of all, from children to adults, within all educational or learning institutions of any kind, within their regular classes and in special classes if called for.”[40]

Law 220 bans schools or learning institutions from making admissions decisions based “upon the soundness of an individual’s constitution, body, or abled-ness, or lack of handicap, infirmity, defect or other formulations.”[41]

The law further states that “any applicant with a disabled ID card” has the right to “pursue studies in the educational or learning institution of his choice, by ensuring favorable conditions to allow him to take entrance exams and all other testing during the school year in every occupational or university stage.”[42]

The law sets out accessibility standards for the construction of buildings intended for public use, sets a hiring quota of three percent for persons with disabilities for public and private businesses, creates committees to write and implement rules that would support people with disabilities, and codifies the right to health, transportation, and education—among others—for people with disabilities.[43]

According to Law 220, the Ministry of Education and Higher Education is responsible for costs associated with the education of children with disabilities.[44] Law 220 stipulates that MOSA is responsible for all decisions related to whether an individual receives a disability card and what services, equipment, or tax benefits that person receives.[45]

The law also creates a number of committees charged with developing and implementing policies to support persons with disabilities. The Disabled and Special Needs Education Committee, for example, which must include a person with a disability from the National Commission for Disability Affairs, is charged with organizing all matters related to the education of persons with disabilities, including procedures and techniques for setting optimal conditions to allow every student who holds a disability card to participate in all classes and tests in all academic, occupational, and university stages.[46]

The committee is also charged with providing advice, technical and educational assistance, and necessary guidance to all educational institutions where persons with disabilities access education.[47] Finally, the committee is supposed to establish a national audio library, a national raised-print library, and a unified sign language.[48] Further committees exist to create and implement policies around different areas of life for persons with disabilities such as sports and transportation.[49]

However, while Law 220 is wide ranging and ambitious, 18 years after it was passed only a fraction of its provisions have been implemented, particularly with regard to education.[50] The committees, for instance, have rarely met, and they have implemented almost no policies to ensure access to education or reasonable accommodations while in school.[51] Neither the Ministry of Education and Higher Education nor the Ministry of Social Affairs have implemented the articles on reasonable accommodation in Law 220. Furthermore, the law still perpetuates the idea of segregated, special schools and should be revised to reflect the current global thinking on inclusive education.

Recent Developments

There have been some positive developments in recent years to improve access to education for children with physical, sensory, and learning disabilities—although not children with intellectual or psychosocial disabilities—in public schools in Lebanon.[52]

The Ministry of Education and Higher Education has begun working on a project for the 2018 academic year to provide 30 of the public schools in Lebanon with full-time specially-trained teachers and a mobile team of school aides that can provide extra support for children with learning disabilities and physically accessible facilities for children with physical disabilities. In addition, with the help of the UN Children’s Agency (UNICEF) and a German development organization, the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ), 20 public schools have been refurbished so their physical infrastructure is accessible to children with physical disabilities.

To cover some of the gaps in educational services provided by the government to children with physical, sensory, and learning disabilities, nongovernmental organizations have in recent years provided accommodations for children with certain disabilities in public schools. For example, the Youth Association for the Blind (YAB) provides typewriters and academic material in Braille as well as trained teachers who can shadow children with visual disabilities and teach children to read and write in Braille. This past year, YAB supported 22 students, and their parents, so the children could attend public school.[53] Organizations like Trait d’Union and the Lebanese Center for Special Education have also conducted trainings and provided some resources in public schools to help children with “learning difficulties” receive extra support.[54] This normally involves break-out classrooms where children receive more personalized attention in smaller group settings.

II. Barriers to Inclusive and Quality Education

“While exclusion might not be a policy, it has become the custom.”

—Sylvanna Lakkis, President of the Lebanese Physical Handicap Union, Beirut, July 5, 2017

Under international human rights law, all children have a right to free, inclusive, quality primary education, free from discrimination. However, many children with disabilities in Lebanon find themselves completely excluded from any educational opportunities.

Children with disabilities in Lebanon are often denied admission to schools because of their disability. Families said school officials gave different, sometimes brutal, reasons for denying their children admission.

Rana, a 25-year-old with an intellectual disability, was told at 8 years old that she had to leave school because she was “taking the spot of another student,” her mother recalled. “They would sit her in the courtyard.” Rana never returned to school.[55]

Cultural stigma around disability in Lebanon is an underlying factor for this denial of education. One family said that a teacher told them their child, who has a learning disability, “should sell gum or graze cattle” rather than be in school.[56] A Ministry of Social Affairs official in Hermel estimated that 80 percent of families with children with disabilities do not send them to school but rather keep them at home, and that the main motivation for this is shame. Such an assessment is consistent with UNICEF’s finding that globally, “The greatest barriers to inclusion of children with disabilities are stigma, prejudice, ignorance and lack of training and capacity building.”[57]

The UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities has stated, “it is necessary to change attitudes towards persons with disabilities in order to fight against stigma and discrimination, through ongoing education efforts, awareness-raising, cultural campaigns and communication.”[58]

Even when children with disabilities are allowed to attend school, they are not provided a quality education because of a lack of reasonable accommodations, accessible materials, and discriminatory fees and expenses.

Public Schools

“In public schools, the government doesn’t allow children with disabilities. Especially if they look like they have a disability, they will not be allowed in.”

—Public school teacher, Hermel, February 16, 2017

There are 1,279 public schools in Lebanon, which the Ministry of Education and Higher Education (MEHE) funds and supervises.[59] In an interview with Human Rights Watch, ministry officials conceded that few schools in the country are inclusive or are even accessible to children with any kind of disability.[60] In the cases Human Rights Watch investigated, most families said children with disabilities were excluded from public schools due to discriminatory admission policies, lack of reasonable accommodations, a shortage of sufficiently trained staff, lack of inclusive curricula (including no individualized education programs), and discriminatory fees and expenses that further marginalize children with disabilities from poor families.

Denial of Admission Due to Disability

Since 2000, Lebanese law has prohibited any restrictions on admissions or entry into any institution of education or learning based on disability.[61] However, Human Rights Watch interviewed 33 children, or their families, who said they were excluded from public schools as a result of discrimination on account of disability.

Sylvanna Lakkis, President of the Lebanese Physical Handicap Union, an advocacy and support group for persons with disabilities, told Human Rights Watch that school directors and teachers who refuse to accept children with disabilities due to their own biases or social stigma face no ramifications. “While exclusion might not be a policy, it has become the custom,” she said.[62] In many cases, the stigma and misconceptions associated with disabilities lead parents, teachers, and school directors to fear having children with disabilities mixed into their student bodies.[63] According to Lakkis, this fear is so widespread that even parents with children who have a disability do not want children with other disabilities in the same class as them.[64]

Amer Makarem, director of the Youth Association for the Blind (YAB), told Human Rights Watch that teachers or school directors have the final say as to whether to include a child: in a number of cases, YAB has either not been able to include a child in a public school or had to stop providing assistance because a school director said he or she did not want a child with a visual disability in the classroom even though YAB was paying for the accommodations.[65]

The perceived cost and burden of including a child with a disability was another factor that excludes children from public schools. One public school director explained that most other directors have the misconception that “including children with disabilities in your school will be a financial burden.”[66]

Arbitrary decisions by local school staff appear to especially harm children with intellectual disabilities. A MEHE representative told Human Rights Watch that children with intellectual disabilities were not included in the public-school system, adding that while this is not official policy, it is the de facto reality since the decision is left to teachers and school directors.[67]

Basmah is a 9-year-old girl with Down Syndrome from Akkar who does not attend public school.[68] Basmah’s parents told Human Rights Watch that she puts on her backpack every day as her siblings get ready for school—but has nowhere to attend.[69] “I would like to go to school,” Basmah said. According to her parents, Basmah was denied enrollment by the principal at her local public school three years ago—the principal said that she “moves a lot” and so she cannot be in class with other children.[70]

Zahraa, a 5-year-old girl living in Hermel, has an intellectual disability.[71] Her mother told Human Rights that she tried to enroll Zahraa in a public school the previous year, but the principal called after a month to inform her that Zahraa had to leave because, “[the teachers] cannot leave all the other children and just take care of her.”[72]

Children with learning disabilities are also excluded from public schools. Human Rights Watch spoke with the mother of Rabih, a 9-year-old living in Beirut who is hyperactive.[73] He used to attend a private school, where “they used to put me out of the class,” Rabih told a Human Rights Watch researcher.[74] His mother tried to enroll him in a public school after the private school’s fees became too high for the family to afford.[75] Rabih’s family said they could not find a public school that would admit him.[76] He was out of school for two years before starting at a MOSA-funded institution.[77]

Barriers to Legal Redress

Although Law 220 has outlawed disability-based discrimination, Ghida Frangieh, a lawyer at Legal Agenda, a Lebanese non-profit that monitors and analyzes law and public policy, said few of the law’s components have been enforced.[78] “While there have been lawsuits focused on the right to work, the right to housing and accessibility of courts, I am not aware of any lawsuit aiming at enforcing the right to education for persons with disabilities,” she told Human Rights Watch.[79]

According to the law, the National Commission for Disability Affairs should undertake the task of filing or intervening in any lawsuit defending the rights of persons with disabilities.[80] However, according to officials who work for the implementing arm of the commission, no lawyer has ever been hired to fill that task.[81]

The law also states that anyone bringing a legal case to enforce their rights can have court fees waived.[82] “A lot of people are not aware of their rights and of the availability of judicial remedies. For instance, few people are aware that judicial fees are waived for complaints related to the disability law,” Frangieh told Human Rights Watch.[83]

Lack of Reasonable Accommodations in Public Schools

Human Rights Watch found that even when children were not explicitly denied admission to a public school, a lack of reasonable accommodations became a barrier to education. In the cases Human Rights Watch documented, it appeared that little to no accommodation is provided in mainstream schools for children with disabilities. One school director told a Human Rights Watch researcher that even though several students with physical disabilities were enrolled at the school, the school building does not meet the basic accessibility standards for persons with physical disabilities as set out in Lebanese law.[84]

In addition to a lack of physical accessibility, public schools lack sufficient, trained staff and appropriate material for a range of learners. Meanwhile, the lack of an individualized approach to children’s education and social development impedes many children with disabilities’ access to a quality education.

A prominent psychiatrist in Lebanon told Human Rights Watch that in general, public school teachers did not give children with learning disabilities extra time to finish an assignment or teach techniques which would allow children to participate in their education on an equal basis with their peers.[85]

According to information provided by MEHE to Human Rights Watch, only four public schools in Lebanon accommodate children with visual disabilities. MEHE officials were not aware of a single school that provided accommodations for children with hearing disabilities. They said less than a tenth of all public schools provide services for children with learning disabilities.[86]

Children with disabilities and their parents told Human Rights Watch that few teachers take the initiative to provide the children with reasonable accommodations and that, in some cases, teachers neglected them.[87]

A child’s right to receive appropriate and reasonable accommodations in school should not depend on whether they have a diagnosis or not. Accommodations in schools should be made by a group of individuals who are knowledgeable about a student’s abilities (parents, older siblings, teachers, counsellor – if there is one) and the types of accommodations that may meet the student’s needs. The teams may review information from the official evaluation, but more importantly, observations, student work samples, report cards, and medical records, to understand the student’s abilities, needs, behaviors, and achievements. The child, parents, and school staff should be included and bring any information they believe best describes the student’s abilities and needs.

According to an assessment of the situation in Lebanon conducted by UNESCO in 2013:

“The majority of schools, at least public schools, are still not fit to accommodate ... students with disabilities. Deficiencies are related to the unavailability [of] proper equipment, buildings, special teaching aids, and qualified special education educators.”[88]

|

Reasonable Accommodation in Practice: Openminds Private actors have taken some positive steps to improve access to an inclusive education for children with disabilities in Lebanon. Openminds, a nonprofit organization established in 2013, donates equipment, pays to refurbish schools and train teachers so that a school can open or expand their inclusive education programs. So far, they have dedicated US$750,000 to six private schools and nine public schools throughout Lebanon. They have given $750,000 for research and $1 million for rehabilitative services for more than 200 persons with disabilities. The organization is helping to facilitate the employment of persons with disabilities, advocating with the government for greater respect for their rights, and providing training to teachers working with children with disabilities. The board, comprised mainly of parents of children with disabilities, is interested in helping fund schools dedicated to providing inclusive educational settings. While this is an important initiative, it is the responsibility of the government to ensure access to quality education for children with disabilities on an equal basis as others. |

Physical Accessibility

Under international human rights and Lebanese law, public buildings, including schools, should, with limited exceptions, be accessible for people with physical disabilities.[89] In fact, few schools in Lebanon are accessible and the government does little to provide accommodations such as structural modifications or ramps.[90]

In 2009, the Lebanese Physical Handicap Union studied public schools in the Beirut and Mount Lebanon governorates—the two governorates considered by advocates and experts to be the most accessible for children with disabilities—and found that only five of the public schools surveyed met all six basic accessibility requirements for persons with physical disabilities: a wheelchair-accessible entrance, ramps where necessary, elevators where necessary, rooms spacious enough for wheelchair mobility, wheelchair-accessible bathrooms, and disability parking.[91]

MEHE representatives acknowledged that not all schools were accessible to students with physical disabilities but said that since 2002, all new schools were built for wheelchair accessibility.[92] However, Human Rights Watch visits to six public schools in the Beirut, Akkar, Nabatieh, and the Chouf districts, and discussion with an administrator about accessibility at a public school in the Hermel district, found that even some of the newer school buildings are currently inaccessible. Two of the schools were constructed after 2002, and—although originally accessible—were no longer accessible by 2017 due to subsequent physical adjustments.[93] For example, one school was split into two separate facilities by a wall, which blocked accessibility to the wheelchair-accessible bathroom for public school students. Human Rights Watch visited a public school in Beirut that used to be accessible but no longer is. According to the school director at Mohammad Chamel Elementary Public School, Mrs. Faten Edelby, there used to be an accessible garage and elevator that provided wheelchair access to pupils, but the municipality rented it in April 2013 and now the school cannot use that entrance.[94]

In Akkar, George Khalil, director of Forum of the Handicapped, a non-governmental group that works toward a better life for persons with disabilities and a more inclusive society, said that he knew of only two out of 166 public schools in the district that admit children who use a wheelchair.[95] Nidal Khoury, the director of Arc En Ciel in Halba, a non-profit dedicated to providing services for persons with disabilities, told Human Rights Watch that he had spoken with multiple families who were moving from Akkar to Tripoli in order to find schools that are physically accessible for their children.[96] Human Rights Watch visited Hrar public school, which according to Ahmad Othman, its director, is one of the only public schools in Akkar that accepts children with physical disabilities.[97] While the school had a wheelchair-accessible bathroom, it is located on the second floor—which is not wheelchair-accessible.

Only two of the six schools Human Rights Watch visited had children with physical and sensory disabilities. Five of the schools failed to meet MEHE’s standards—the ministry’s codification of Article 37 of Law 220 which ensures public buildings are accessible the persons with physical disabilities—because they lacked accessible bathrooms, entrances, classrooms, or lifts when necessary.[98]

According to a 2013 UNESCO report, only five public schools in the country had been made accessible to people with physical disabilities by MEHE.[99]

A public-school director in Akkar told Human Rights Watch that his school accommodates seven students with physical disabilities and two with speech disabilities. However, the school does not meet MEHE’s wheelchair accessibility standards, or provide reasonable accommodations and related support to children with disabilities, according to the director.[100]

In Hermel, municipality officials pointed Human Rights Watch to the largest public school, where 1,430 Lebanese children are enrolled in the “morning shift” and 767 Syrian children are enrolled in the “afternoon shift,” as the best example of a school that provides education to children with disabilities in the area.[101] However, an administrator at the school said that while there is an elevator in the school, the government does not allow it’s use because of the cost of electricity to run it.[102]

In the Chouf district, Human Rights Watch visited two schools that officials or non-governmental staff had said they believed were accessible. One of these schools, Mazraat El Chouf Mixed Intermediate Public School had a ramp and wheelchair-accessible bathroom on the ground floor, but no designated parking or accessibility to other parts of the school. The other, Baaklin public school, had a ramp in the front, but the one wheelchair-accessible bathroom was now part of a different facility, no longer accessible to the public school.[103] Neither of the school’s enrolled students included any children with physical disabilities.

The one public school Human Rights Watch visited that met a majority of the wheelchair accessibility standards was Zebdine public school in Nabatieh, which had an accessible ramp entrance, bathrooms, classrooms, and an elevator. The school also had wheelchairs available for students who entered without one, but needed one for the day.[104] According to Khalil Zahri, the school director, Zebdine is the only accessible school in the Nabatieh district.[105]

In 2016, UNICEF launched a project to refurbish public schools across Lebanon. Of the 61 refurbished in 2016-2017, nine were made wheelchair-accessible.[106] According to UNICEF, 55 of the 123 scheduled to be refurbished in 2017-2018 are supposed to be made wheelchair-accessible.[107] Other organizations such as the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) are engaged in similar projects, where they are working to make another 10 schools accessible for at least the ground floor.[108]

Inclusive education does not have to be costly. For example, to improve physical accessibility it might be sufficient to move a class to the ground floor with no further building modifications necessary. Even where modifications are necessary to ensure that buildings are physically accessible to people with disabilities, making the necessary adjustments usually costs only 1 percent of the overall building cost, according to the World Bank.[109]

Lack of Accessible Educational Materials

Human Rights Watch found that public schools are not equipped with materials, tools, and systems that would enable the inclusion of children with disabilities in mainstream education. This includes a lack of textbooks and learning materials in accessible formats, such as Braille or audiotape, Braille machines, or sign language interpreters.

Lebanon’s local law guarantees these tools and services for children to access education. Law 220 specifically ensures reasonable accommodations for any academic tests including extended time, adjusted test materials (raised letters, large font, etc.), and assistance from other or specific techniques, such as Braille machines, and sign language interpreters. Without these accommodations children with disabilities cannot access a quality education on an equal basis with their peers.

Children and families told Human Rights Watch that visual aids and large print materials are not readily available for children with visual disabilities in public schools.[110] They also do not offer Braille and are not equipped with Braille teachers, except in rare cases.[111] As a result, most students who are blind or have low vision go to MOSA-funded institutions because mainstream schools are reluctant to accept them and provide reasonable accommodations.[112]

In some cases, it is only with the help of NGOs that public schools offer any accessible materials to students with disabilities. Representatives from MEHE told Human Rights Watch that the financial support and training assistance of the Youth Association for the Blind (YAB) was critical for public schools to enroll children with visual disabilities.[113] Amer Makarem, director of YAB, said the organization provides materials such as Braille typewriters and trains teachers to include children with visual disabilities in public schools.[114] He said that for the 2016-2017 school year, YAB helped 22 students in 4 different schools across the country.[115] MEHE representatives told Human Rights Watch that the YAB-assisted students were the only students with visual disabilities enrolled in public schools across the country.[116] There is no accurate data on how many out-of-school children with visual disabilities there are in the country.

In one case, Mustafa, a 26-year-old living in Akkar, told Human Rights Watch that he could not complete school because he did not receive any accommodations for his visual disability, such as raised letters or larger print.[117] Mustafa’s sight deteriorated in the fifth grade, when he began to have trouble seeing the board and reading his textbooks.[118] He dropped out of school two years later.[119] His 28-year-old sister Yasmine, who also has a visual disability, said she also dropped out of primary school because she did not receive any assistance.[120] She believed that in their case, the only benefit they were eligible to receive from their disability card was a tax exemption for purchasing a car. “What am I supposed to do with a car? I’m blind.”[121] Neither of them completed primary education.[122]

According to Makarem, it costs US$4,000 per year to include a child with a visual disability in public school by providing accessible materials, equipment, and teacher training—half the cost of a child attending and sleeping at one of the three main MOSA-supported institutions for children with visual disabilities.[123]

Makarem argued that MEHE should take responsibility for including more children with visual disabilities in public schools. He suggested that MEHE’s Center for Educational Research and Development (CERD), which is charged with setting the curriculum, could print textbooks in Braille to make public schools accessible for blind children.[124] CERD reported that they are working on a new, more interactive and inclusive curriculum.[125]

|

What Inclusive Education Can Look Like: Zebdine Public School in Nabatieh Human Rights Watch researchers visited Zebdine public school, the only YAB-supported school in Nabatieh. As we arrived, Abbas, a 13-year-old, blind boy in sixth grade, was in the courtyard being led by a female classmate as they played tag with other students. “Sometimes the other children are jealous because everyone wants to be friends with [the children with disabilities],” Khalil Zahri, the school director, told Human Rights Watch. Abbas said that he loved school. “Honestly all the topics are great … I am friends with everyone in my class.” Abbas works privately with a specialist to read and write in Braille on a machine that YAB provides. He also receives all his academic material in Braille. |

Shortage of Sufficient, Trained Staff

“We lack people who can teach my daughter.”

—Mother of a 7-year-old girl with an intellectual disability, Hermel, April 2, 2017

An important part of ensuring reasonable accommodation is training teachers, school administrators, and education officials in methods to support children with disabilities in the classroom. Without this support, a child’s education will be hindered at best, and completely denied at worst.

Maher, a 7-year-old boy with a speech disability living in Hermel, attends a local public school there.[126] “It gets him really angry and sad when someone mocks him [about his speech],” Maher’s mother said.[127] Maher’s parents said that he memorizes the material, but the teachers do not understand him in class.[128] “I like my friends at school and math class, but I don’t like my Arabic teacher. She gives me Xs,” Maher told a Human Rights Watch researcher. The school does not provide Maher with speech therapy, his parents said, yet school officials told them that if his speech does not improve, he will be expelled.[129] The family cannot afford a speech therapist.[130] Without this support, Maher’s educational progress is suffering and the chances of him being able to stay in school are slim, his parents fear.[131]

The consequences of failing classes that do not accommodate children with disabilities is borne by the children and their families. A school director informed Human Rights Watch that it is MEHE policy to expel a child if they fail three years of school.[132]

Human Rights Watch visited schools and families across Lebanon, and found in nearly all cases that teachers and school administrators lack training in inclusive education methods and schools lack funding to provide support to teachers to make accommodations. The few teachers who were trained to support children with disabilities were restricted from dedicating time to do so. For example, one school had just one teacher who was trained to provide additional support for children with disabilities, but the teacher could only dedicate 25 percent of her time to that task, as the rest of her time was needed elsewhere.[133] The school’s administrator told Human Rights Watch that the school would need four full-time teachers to meet the needs of students with disabilities.[134]

Layal, a 12-year-old girl with a hearing disability living in Saida, told Human Rights Watch that she would like to go to the public school close to home with her six siblings.[135] But because no one in the school can communicate with her in sign-language, she said, each day she travels 40 minutes to a MOSA-funded institution, where she receives an education alongside other children with disabilities.[136] The specialized institution provides education only until 9th grade and does not prepare children for the brevet, the test required for admissions to secondary school.[137] Layal wants to become a doctor, but is worried that she will not have academic opportunities after grade 9.[138]

According to Rima Allawi, director of Child First Association in Hermel, a private facility that offers speech therapy, academic help, and physical therapy, the children with hearing disabilities in public schools in the Hermel district do not receive reasonable accommodations, such as speech therapy. Without such support services, children are not able to participate in the classroom and eventually are expelled.[139]

Most of the children with hearing or speech disabilities whom Human Rights Watch researchers met did not have the help of a speech therapist. Many schools also lack staff who are trained to effectively communicate material to children with different learning styles. One public school administrator summarized a viewpoint common to all the administrators whom Human Rights Watch spoke with about children with disabilities: “We are trying to do the best we can, we don’t have resources or the tools we need. We need specialists.”[140]

A child psychiatrist confirmed to Human Rights Watch that the public schools are severely understaffed and under-resourced.[141] He noted that the lack of trained staff and early screening in public school is highly problematic because when disabilities go undedicated and unaddressed, more damage is done to the child’s educational progress.[142]

Ahmed, a 5-year-old with a speech disability, attends a public school in Akkar. His mother told a Human Rights Watch researcher that Ahmed does not have access to speech therapy in the school and she cannot pay for a private therapist—around LBP50,000 a month (US$33) for one session every other week. The local public school has already made him repeat a year and told her that Ahmed will be asked to leave at the end of the year if he does not significantly improve. Aside from the cost, his mother said that bringing Ahmed to the speech therapist is difficult due to the distance. “There should be a speech therapist in the school,” she said. Ahmed’s access to education will be impeded if the school does not provide the educational support he needs.

Rami, a 14-year-old boy living in Beirut who has a physical and an intellectual disability, does not receive adequate support in school.[143] His mother, Nour, told Human Rights Watch that she is concerned about Rami staying in his current school because “there is no one to help him,” and that “seeing friends getting high grades affects him negatively when he struggles and does not.”[144] Rami said that he does not want to leave his school, but his remarks imply that he relies more on his friends than on school staff for support: “I want to stay at the same school. My friends help me and are always beside me,” he said proudly.[145]

Kareem is a 12-year-old boy living in the Chouf region.[146] He has a learning disability, but although he has already changed schools and repeated two years of school, he still does not have access to trained teachers and educational support.[147] According to Kareem’s mother, the school he currently attends says that he is not learning in class.[148] However, when Kareem’s mother asked the school to provide classroom support, they responded: “One teacher cannot sit with him and leave the rest of the class.”[149] Kareem’s mother is worried that without some change, he will continue to fail and be asked to leave school.[150]

Five of the schools Human Rights Watch visited had implemented the Lebanese Centre for Special Education (CLES) program, and teachers said they found it helpful. CLES is one of four programs (including SKILD, Restart, and Trait d’Union) that provide educational training to teachers so that they are prepared to give support to children who struggle academically.

The CLES program is also establishing learning support classrooms in 200 of Lebanon’s 1,279 public schools.[151] Children attend one-on-one or small group instruction in these learning support classrooms. The program is geared toward first, second, and third graders with what MEHE terms “learning difficulties.” Children do not receive this potentially vital support unless they have been diagnosed with a learning difficulty, fall into that age range, and are at one of these schools. Many have a learning disability but have not been assessed as needing the support.

Teachers said that children who did receive extra help from the CLES program benefited substantially. “We wish this CLES program would spread all over Lebanon,” a CLES instructor said.[152] “It gives us motivation that the children are happy and want to learn. Sometimes children outside the program want to join.”[153] However, the same teachers said they still did not have the resources they needed to appropriately accommodate all students and that there was not enough follow-up from CLES to ensure the quality and implementation of the program.[154]

Human Rights Watch found that the lack of trained teachers and other academic staff to support children with disabilities was partially due to a lack of opportunities to obtain that training. According Asma Azar, senior lecturer in special education at the University of Saint Joseph (USJ) in Beirut, there are only six centers in Lebanon that train teachers on inclusive education methods.[155] Azar estimates that around 60 students graduate from these programs every year, but many change fields or go to other Arabic-speaking countries.[156] “We do not have enough teachers in relation to the students,” she said.[157] “Most of the [instructors] in special education are not qualified.”[158]

Instead, all teachers should be trained in inclusive education methods, which have a track record of benefitting all children, not just children with disabilities.[159]

In Akkar, representatives at First Step Together Association (FISTA) North, an association of schools for children with intellectual disabilities based in north Lebanon, told Human Rights Watch that “there is a lack of human resources,” including just one speech and one psychomotor therapist in the Akkar district, for an estimated population of around 330,000 people.[160] A MOSA official told Human Rights Watch that there were only two psychotherapists, one specialist in ergotheraphy (a form of therapy that uses physical activity to support persons with disabilities in basic life activity), and no speech therapists in the Chouf (with a population of some 166,140 people).[161]

According to the same official, specialists mainly came from Beirut to service the district.[162] Dr. Weam Abou Hamdan, director of the National Rehabilitation and Development Center in the Chouf, similarly told Human Rights Watch that it was particularly difficult to find a qualified team of specialists.[163]

Human Rights Watch found an even worse situation in Hermel, a district with an estimated 48,000 people.[164] According to a MOSA official, there is only one speech therapist who travels regularly to Hermel from Beirut.[165] The same official told Human Rights Watch that there were no speech therapists in Baalbek, the nearest city.[166] Heba lives in Hermel with her 6-year-old, Nadine, who has a physical and an intellectual disability. Heba explained to Human Rights Watch, “We lack people who can teach my daughter.... We wish they offered physical therapy or ergotherapy in the area.”[167]

Discriminatory Fees and Expenses

“If you don’t have a good income, the child has no hope.”

—Mother of a 12-year-old child with a disability, Beirut, April 13, 2017

Children with disabilities who attend public schools must often pay more fees than children without disabilities. These include additional transportation fees (i.e., specially outfitted vehicles or assistants), fees for classroom assistants, homework helpers, speech therapists, and other related support services outside school. These services are not only necessary to ensure a quality education, but in some cases, are required by schools for students to remain enrolled.

Under the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), discrimination is any “distinction, exclusion or restriction … which has the purpose or effect of impairing or nullifying the recognition, enjoyment or exercise, on an equal basis with others, of all human rights and fundamental freedoms.”[168]

Human Rights Watch spoke with 29 families who had children paying for or hoping to find supplemental services to compensate a lack of reasonable accommodations at their public school in Akkar, Beirut, the Chouf, Hermel, and Nabatieh.