“Here we don’t talk about sex,” was how a diplomat in 2007 responded when I tried to talk about LGBT rights at the United Nations, shortly after I joined Human Rights Watch as advocacy director for the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) rights program. As I prepare to leave the organization, it’s clear there have been remarkable changes during my tenure here. Back then, I had to explain to the diplomat that discussing LGBT rights means talking about equality and non-discrimination, privacy, freedom to think and to speak out, to gather peacefully with other people, to form a family, to name just a few. No special treatment, just the same fundamental rights to which all human beings are entitled.

The Yogyakarta Principles, developed in 2006, proved to be an excellent tool to demonstrate the enormous gap between universally recognized human rights and the everyday realities experienced by LGBT people. Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay took the lead in launching the Yogyakarta Principles at the UN headquarters in New York in November 2007 – three Latin American countries with strong Roman Catholic constituencies, rather than the usual Western suspects.

At that UN launch, Mary Robinson, a former UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, referred to article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and made a strong plea to treat LGBT people with dignity and respect. This was the first event organized by a group of LGBT-friendly countries at the United Nations. This informal UN network, co-founded by Human Rights Watch, plays an important role in strategizing at the UN how to improve the rights of LGBT people, counter violence and discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity, and dealing with the opposition towards progress. And opposition there was.

In 2008, 57 countries led by Syria signed a petition against the rights of LGBT people by claiming that non-discrimination of LGBT people could lead to paedophilia and adultery. A driving force behind this statement was the Holy See of the Catholic Church, the only religion with speaking rights at UN meetings. Dismayed about how dangerous this hostility is to LGBT people I negotiated with the Holy See to present their vision on sexual orientation and gender identity in a public meeting at the UN. At the next meeting in the UN in New York in 2009, the Holy See showed a different face and delivered a statement opposing violence and “unjust” discrimination against homosexual persons and denounced criminalization of homosexual conduct. It was a watershed moment: Human Rights Watch still refers to this statement in countries where homosexual conduct is criminalized and there is a strong Christian influence ostracizing LGBT people, such as in the eastern Caribbean.

However, even though the Holy See clarified its position, religion is often the source of discrimination. In 2018, we published “All We Want is Equality,” a report about how religious exemptions are used to discriminate against LGBT people in the United States. I see the tension between freedom of religion and the rights to equality and non-discrimination in many countries.

Violence and discrimination can start early on: bullying at school because of sexual orientation or gender identity is a nasty and persistent problem. In 2001 Human Rights Watch published “Hatred in the Hallways,” a report on LGBT youth in US schools subjected to daily abuse by their peers and even by teachers and school administrators. These violations were compounded, we found, by the failure of federal, state, and local governments to enact laws protecting LGBT students from discrimination and violence, effectively allowing school officials to ignore violations of their rights.

Bullying can lead to students dropping out, self-harm or even suicide, so Human Rights Watch has continued to investigate the right to education and bullying. In 2016, “Like Walking Through a Hailstorm” revisited the problem in US schools, finding that in many states and school districts LGBT students and teachers lack protections from discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity. In others, protections that do exist are inadequate and not enforced. We also reported on school bullying in Japan and the Philippines. Our reporting in Japan prompted a change in government policy and recently Japanese schools introduced uniforms designed to respect gender expression by allowing students to choose their attire.

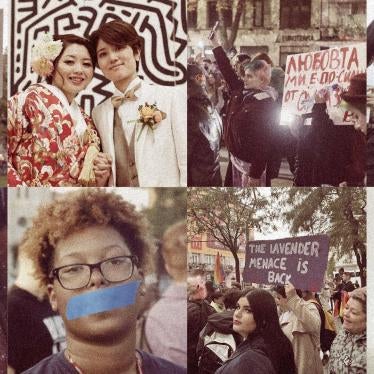

The persecution can persist: in more than 70 countries same-sex sexual intimacy is a crime. And in many countries where it is not expressly forbidden, there are often laws or policies that make life for LGBT people very difficult. In Russia, for instance, the anti-gay propaganda law is used to impose fines against people who publicly display positive information on homosexuality.

Fortunately, there are positive examples. Mozambique decriminalized homosexual conduct in 2015. The Supreme Court of Belize declared the sodomy law unconstitutional in 2016. And in Trinidad and Tobago the High Court of Justice ruled in 2018 that the laws criminalizing same-sex intimacy are unconstitutional. The Indian Supreme Court could soon strike down a 158-year-old colonial-era law that makes “carnal intercourse against the order of nature” illegal. This would be a huge step forward for a country with more than 1.3 billion people that would, as a matter of law, respect the dignity and the rights of LGBT people.

Some of these gains were supported by strong leadership at the UN from then-UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon. He addressed sexual orientation and gender identity prominently in speeches, becoming a staunch supporter of LGBT rights. Even in meetings with homophobic African leaders he talked about the need to decriminalize same-sex sexual activities. Under Ban’s watch the UN Human Rights Council passed two resolutions in favor of LGBT rights and created a new position of independent expert on sexual orientation and gender identity.

Over this past decade I have seen transgender activists become more vocal and influential, especially around getting governments to recognize gender without imposing harmful requirements. At the request of Dutch activists, Human Rights Watch undertook research on the legal situation for trans people in the Netherlands, which is often praised for being at the forefront of LGBT rights. We found that Dutch law forced transgender people to undergo sex-reassignment surgery, hormone treatment and psychiatric evaluation before being allowed to obtain identification documents reflecting their gender identity. In 2011 we presented our report to the Dutch government, highlighting a new Argentinean gender recognition law as a great example. Three years later, the new Dutch law doing away with these requirements came into effect.

And intersex activists have pushed a new human rights issue on to the policy agenda: of medically unnecessary surgery performed on intersex children without their consent. Together with InterAct, a US group, we investigated this practice in the US in a 2017 report “I Want to Be Like Nature Made Me.” Such medically unnecessary surgery occurs in many countries. On August 28, California’s legislature passed a resolution that supports the autonomy of intersex people and their right to decide about cosmetic surgical alteration.

And who could forget the incredible developments towards marriage equality? As a member of the Dutch parliament in the 1990s, my resolutions to legalize same-sex marriage were adopted by the majority in parliament. It took seven years, but in 2001 the Netherlands became the first country in the world where same-sex couples could get married. Seventeen years later, 25 countries have marriage equality and Austria and Taiwan are expected to follow in 2019.

All these positive steps have come through the tenacity and perseverance of many LGBT activists and their allies, often in very difficult circumstances. I am so proud to have worked with them and to have been part of this inspiring movement.

For me, the circle is almost complete: after my political career in the House of Representatives of the Netherlands I joined Human Rights Watch. And now, after more than 11 years as the LGBT advocacy director, I will start campaigning for a seat in the Dutch Senate. I hope to be elected in 2019.

The future is not in front of us, it’s inside of us.