Summary

It’s like walking through a hailstorm...

—Polly R. (pseudonym), parent of gender non-conforming son, describing the hostile environment that LGBT children face in schools, Utah, December 2015

Outside the home, schools are the primary vehicles for educating, socializing, and providing services to young people in the United States. Schools can be difficult environments for students, regardless of their sexual orientation or gender identity, but they are often especially unwelcoming for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth. A lack of policies and practices that affirm and support LGBT youth—and a failure to implement protections that do exist—means that LGBT students nationwide continue to face bullying, exclusion, and discrimination in school, putting them at physical and psychological risk and limiting their education.

In 2001, Human Rights Watch published Hatred in the Hallways: Violence and Discrimination against Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Students in US Schools. The report documented rampant bullying and discrimination against LGBT students in schools across the country, and urged policymakers and school officials to take concrete steps to respect and protect the rights of LGBT youth.

Over the last 15 years, lawmakers and school administrators have increasingly recognized that LGBT youth are a vulnerable population in school settings, and many have implemented policies designed to ensure all students feel safe and welcome at school.

Yet progress is uneven. In many states and school districts, LGBT students and teachers lack protections from discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity. In others, protections that do exist are inadequate or unenforced. As transgender and gender non-conforming students have become more visible, too, many states and school districts have ignored their needs and failed to ensure they enjoy the same academic and extracurricular benefits as their non-transgender peers.

This undermines a number of fundamental human rights, including LGBT students’ rights to education, personal security, freedom from discrimination, access to information, free expression, association and privacy.

Based on interviews with over 500 students, teachers, administrators, parents, service providers, and advocates in Alabama, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, Texas, and Utah, this report focuses on four main issues that LGBT people continue to experience in school environments in the United States.

Areas of concern include bullying and harassment, exclusion from school curricula and resources, restrictions on LGBT student groups, and other forms of discrimination and bigotry against students and staff based on sexual orientation and gender identity. While not exhaustive, these broad issues offer a starting point for policymakers and administrators to ensure that LGBT people’s rights are respected and protected in schools.

LGBT Experiences in School

Social pressures are part of the school experience of many students, regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity. But the experience can be particularly difficult for LGBT students, who often struggle to make sense of their identities, lack support from family and friends, and encounter negative messaging about LGBT people at school and in their community.

As a result of these factors, LGBT students are more likely than heterosexual peers to suffer abuse. “I’ve been shoved into lockers, and sometimes people will just push up on me to check if I have boobs,” said Kevin I., a 17-year-old transgender boy in Utah. He added that school administrators dismissed his complaints of verbal and physical abuse, blaming him for being “so open about it.”

In some instances, teachers themselves mocked LGBT youth or joined the bullying. Lynette G., the mother of a young girl with a gay father in South Dakota, recalled that when her daughter was eight, “she ran home because they were teasing her. Like, ‘Oh, your dad is a cocksucker, a faggot, he sucks dick.’ … She saw a teacher laughing and that traumatized her even worse.”

Students also reported difficulty accessing information about LGBT issues from teachers and counselors, and found little information in school libraries and on school computers. In some districts, this silence was exacerbated by state law. In Alabama, Texas, Utah, and five other US states, antiquated states laws restrict discussions of homosexuality in schools. Such restrictions make it difficult or impossible for LGBT youth to get information about health and well-being on the same terms as heterosexual peers. “In my health class I tested the water by asking [the teacher] about safer sex, because I’m gay,” Brayden W., a 17-year-old boy in Utah, said. “He said he was not allowed to talk about it.”

The effects of these laws are not only limited to health or sexuality education classes. As students and teachers describe in this report, they also chilled discussions of LGBT topics and themes in history, government, psychology, and English classes.

Many LGBT youth have organized gay-straight alliances (GSAs), which can serve as important resources for students and as supportive spaces to counteract bullying and institutional silence about issues of importance to them. As this report documents, however, these clubs continue to encounter obstacles from some school administrators that make it difficult for them to form and operate.

When GSAs were allowed to form, some students said they were subject to more stringent requirements than other clubs, were left out of school-wide activities, or had their advertising defaced or destroyed. Serena I., a 17-year-old bisexual girl in Utah, said: “It’s mental abuse, almost, seeing all these posters up and yours is the only one that’s written on or torn down.”

Often, LGBT students also lacked teacher role models. In the absence of employment protections, many LGBT teachers said they feared backlash from parents or adverse employment consequences if they were open about their sexual orientation or gender identity.

Discrimination and bigotry against transgender students took various forms, including restricting bathroom and locker room access, limiting participation in extracurricular activities, and curtailing other forms of expression—for example, dressing for the school day or special events like homecoming. “They didn’t let me in and I didn’t get my money back,” said Willow K., a 14-year-old transgender girl in Texas who attempted to wear a dress to her homecoming.

LGBT students also described persistent patterns of isolation, exclusion, and marginalization that made them feel unsafe or unwelcome at school. Students described how hearing slurs, lacking resources relevant to their experience, being discouraged from having same-sex relationships, and being regularly misgendered made the school a hostile environment, which in turn can impact health and well-being.

Acanthus R., a 17-year-old pansexual, non-binary transgender student in Utah, said it was “like a little mental pinch” when teachers used the wrong pronouns. “It doesn’t seem like a big deal, but eventually you bruise.”

Comprehensive approaches are urgently needed to make school environments welcoming for LGBT students and staff, and to allow students to learn and socialize with peers without fearing exclusion, humiliation, or violence. Above all:

- States should repeal outdated and stigmatizing laws that deter and arguably prohibit discussion of LGBT issues in schools, and enact laws protecting students and staff from bullying and discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity.

- Schools should ensure that policies, curricula, and resources explicitly include LGBT people, and that the school environment is responsive to the specific needs of LGBT youth.

- Teachers and administrators should work to make existing policies meaningful by enforcing protections and intervening when bullying or discrimination occurs.

Key Recommendations

To State Legislatures

- Ensure that state laws against bullying and harassment include enumerated protections on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity;

- Ensure that state non-discrimination laws include explicit protections from discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity, particularly in education, employment, and public accommodations;

- Repeal laws that preclude local school districts from providing enumerated protections against discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity;

- Repeal laws that prohibit or restrict discussion of LGBT issues in schools.

To State Departments of Education

- Ensure that teachers, counselors, and other staff receive training to familiarize them with the issues LGBT students might face;

- Promulgate model guidelines for school districts to follow to make schools safe and inclusive for LGBT youth.

To School Administrators

- Ensure that school policies against bullying and harassment include enumerated protections on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity;

- Ensure that the school provide comprehensive sexuality education that is inclusive of LGBT youth, covers same-sex activity on equal footing with other sexual activity, and is medically and scientifically accurate;

- Ensure that GSAs and other LGBT student organizations are permitted to form and operate on the same terms as all other student organizations;

- Ensure that same-sex couples are able to date, display affection, and attend dances and other school functions on the same terms as all other student couples;

- Ensure that students are able to access facilities, express themselves, and participate in classes, sports teams, and extracurricular activities in accordance with their gender identity.

To the US Congress

- Enact the Equality Act or similar legislation to prohibit discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity in employment, education, federal funding, and public accommodations;

- Enact the Student Non-Discrimination Act or similar legislation to prohibit discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity in schools;

- Enact the Safe Schools Improvement Act or similar legislation to encourage states to enact strong policies to prevent bullying and harassment that are inclusive of sexual orientation and gender identity;

- Enact the Real Education for Healthy Youth Act or similar legislation to support comprehensive sexuality education and restrict funding to health education programs that are medically inaccurate, scientifically ineffective, or unresponsive to the needs of LGBT youth.

Methodology

Human Rights Watch conducted research for this report between November 2015 and May 2016 in five US states: Alabama, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, Texas, and Utah. The sites were chosen as a regionally diverse sample of states that, at time of writing, lacked enumerated statewide protections against bullying and discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity in schools.

Human Rights Watch contacted potential interviewees through nongovernmental organizations, LGBT organizations in high schools and middle schools, and LGBT organizations in post-secondary institutions where recent graduates reflected on their high school experiences. The research focused on public schools, including public charter schools, rather than private schools that enjoy greater autonomy to act in accordance with their particular beliefs under US law.[1] Researchers spoke with 358 current or former students and 145 teachers, administrators, parents, service providers, and advocates for LGBT youth.

All interviews were conducted in English. No compensation was paid to interviewees. Whenever possible, interviews were conducted one-on-one in a private setting. Researchers also spoke with interviewees in pairs, trios, or small groups when students asked to meet together or when time and space constraints required meeting with members of student organizations simultaneously.

Researchers obtained oral informed consent from interviewees, and notified interviewees why Human Rights Watch was conducting the research and how it would use their accounts, that they did not need to answer any questions they preferred not to answer, and that they could stop the interview at any time. When students were interviewed in groups, those who were present but did not actively participate and volunteer information were not recorded or counted in our final pool of interviewees.

In this report, pseudonyms are used for interviewees who are students, teachers, or administrators in schools to protect their privacy and mitigate the risk of adverse consequences for participating in the research. Unless requested by interviewees, pseudonyms are not used for individuals who work in a public capacity on the issues discussed in this report.

Glossary

Agender: Does not identify with any gender.

Aromantic: Experiences little or no romantic attraction to other people.

Asexual: Experiences little or no sexual attraction to other people.

Biromantic: Romantically attracted to two or more sexes or genders.

Bisexual: Sexually or romantically attracted to two or more sexes or genders.

Cisgender: Sex assigned at birth conforms to identified or lived gender.

Demiboy: Only partly male, regardless of sex assigned at birth.

Demigirl: Only partly female, regardless of sex assigned at birth.

Demisexual: Feels attraction only to those with whom they have a strong emotional bond.

Gay: Male is primarily sexually or romantically attracted to other males.

Genderfluid: Gender fluctuates and may differ over time.

Gender Identity:Deeply felt sense of being female or male, neither, both, or something other than female and male. Does not necessarily correspond to sex assigned at birth.

Gender Non-Conforming: Does not conform to stereotypical appearances, behaviors, or traits associated with sex assigned at birth.

Genderqueer: Identifies as neither male nor female, both male and female, or a combination of male and female, and not within the gender binary.

Lesbian: Female is primarily sexually or romantically attracted to other females.

LGBT: Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender.

Non-Binary: Identifies as neither male nor female.

Pansexual: Sexual or romantic attraction is not restricted by sex assigned at birth, gender, or gender identity.

Sexual Orientation: Sense of attraction to, or sexual desire for, individuals of the same sex, another sex, both, or neither.

Transgender: Sex assigned at birth does not conform to identified or lived gender.

I. Background

Successes, with Limits

LGBT communities in the United States have won a number of victories over the past decade. Among other milestones, advocates have successfully fought to include sexual orientation and gender identity in federal hate crimes legislation,[2] repeal the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy that banned LGBT persons from serving in the US military,[3] and prohibit discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity in employment by the federal government and its contractors and subcontractors.[4] The US Supreme Court has also extended the constitutional right to marry to same-sex couples nationwide.[5]

In contrast to these positive trends, many LGBT youth still remain vulnerable to stigmatization and abuse. In a survey of more than 10,000 youth conducted in 2012, a lack of family acceptance was the primary concern that LGBT youth identified as the most important problem in their lives.[6] Due in part to rejection by families and peers, LGBT youth have disproportionately high rates of homelessness, physical and mental health concerns, and suicidality. Only five US states and the District of Columbia have prohibited “conversion therapy,” a dangerous and discredited practice meant to change a person’s sexual orientation or gender identity.[7]

When LGBT youth experience family or community rejection, schools can ideally function as safe and affirming environments for them to learn, interact with peers, and feel a sense of belonging. Yet efforts to ensure such conditions for LGBT youth in schools have historically encountered strong political, legal, and cultural resistance, and continue to face such resistance today, often due to the charge that adults are “indoctrinating” or “recruiting” youth into being LGBT.

In 1977, Anita Bryant’s “Save Our Children” campaign relied heavily on this type of child-protective rhetoric to repeal a Dade County, Florida ordinance prohibiting discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, and inspired a number of copycat campaigns around the United States.[8]

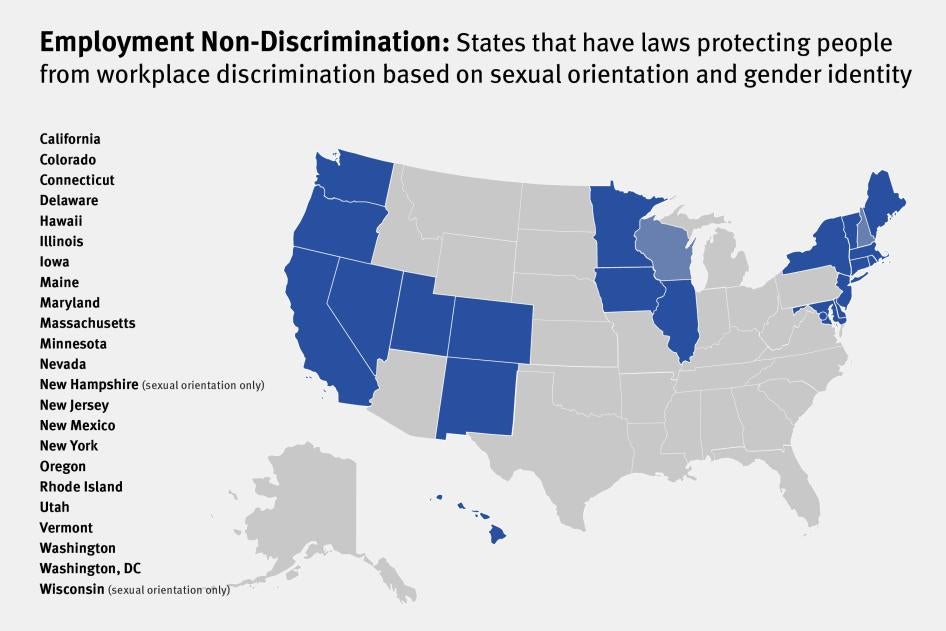

Nearly 40 years later, many teachers who are visibly out as LGBT or actively support LGBT students still worry that they will be passed over for promotions, demoted, or terminated as a result.[9] Such concerns are not unfounded; most US states still lack laws prohibiting discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity in the workplace.[10]

In the late 1980s, lawmakers began amending sexuality education laws and inserting provisions that many educators read as prohibiting or restricting discussions of homosexuality in schools. Such laws have been decried as discriminatory and nonsensical, yet they remain on the books in eight US states.[11] Attempts to repeal them have proved unsuccessful, and lawmakers in Missouri and Tennessee have pushed in recent years to adopt similar laws in their states.[12]

When students themselves began organizing in the 1990s, many school administrators across the US unsuccessfully fought to restrict the formation and operation of gay-straight alliances (GSAs) in schools, arguing that the clubs were inappropriate for youth. Although courts have clearly and repeatedly affirmed that schools must allow such groups to form, dogged resistance to GSAs continues in many school systems.[13]

And in 2016, anxieties about LGBT youth in schools emerged anew when lawmakers in at least 18 states sought to restrict transgender students’ access to bathrooms, locker rooms, and other facilities consistent with their gender identity.[14] Despite significant changes in public opinion toward LGBT people, resistance to policies that render schools safe and affirming leave LGBT students and faculty vulnerable in too many schools across the US.

“No Promo Homo” Laws

In some instances, pervasive anxieties about indoctrination and recruitment in schools have prompted state and local efforts—some of them successful—to limit what teachers may say about LGBT topics in the classroom.

One of the most overt campaigns to keep LGBT topics out of schools was the Briggs Initiative, a ballot measure in California in 1978 that would have prohibited “the advocating, soliciting, imposing, encouraging or promoting of private or public homosexual activity directed at, or likely to come to the attention of, schoolchildren and/or other employees.”[15]

Although the Briggs Initiative was defeated, laws prohibiting the promotion of homosexuality or restricting discussions of homosexuality in schools were enacted by state legislatures in the late 1980s and 1990s. Laws that restrict classroom instruction in this manner—or “no promo homo” laws—remain on the books in Alabama, Arizona, Louisiana, Mississippi, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Texas, and Utah.[16]

The provisions in Alabama, Mississippi, and Texas refer to homosexuality as a criminal offense under state law, ignoring that the Supreme Court deemed those criminal laws unconstitutional in 2003.[17] Of the five states where interviews took place, Alabama, Texas, and Utah each have laws pertaining to discussions of homosexuality in schools:

- Alabama state law dictates that “[c]ourse materials and instruction that relate to sexual education or sexually transmitted diseases should include all of the following elements … [a]n emphasis, in a factual manner and from a public health perspective, that homosexuality is not a lifestyle acceptable to the general public and that homosexual conduct is a criminal offense under the laws of the state.”[18]

- Texas state law specifies that the Department of State Health Services “shall give priority to developing model education programs for persons younger than 18 years of age,” and “[t]he materials in the education programs intended for persons younger than 18 years of age must … state that homosexual conduct is not an acceptable lifestyle and is a criminal offense under Section 21.06, Penal Code.”[19]

- Utah state law prohibits public schools from using materials for “community and personal health, physiology, personal hygiene, and prevention of communicable disease” that include instruction in “the intricacies of intercourse, sexual stimulation, or erotic behavior; the advocacy of homosexuality; the advocacy or encouragement of the use of contraceptive methods or devices; or the advocacy of sexual activity outside marriage.”[20]

They appear alongside more general restrictions on sexuality education, including provisions requiring or encouraging abstinence education. Although each of these restrictions specifically appears in portions of state law addressing instruction in sexuality education, their chilling effects often extend much further.

As Nora F., an administrator in Utah, said:

The law says you can’t do four things – advocate for sex outside of marriage, contraception, homosexuality, and can’t teach the mechanics of sex. It’s in the realm of sexuality education, but these four things transcend health classes. This is why history teachers might hesitate to teach an LGBT rights lesson, or why elementary school teachers might hesitate to read a book with LGBTQ themes.[21]

As interviews with administrators, teachers, and students demonstrate, the practical effect of these outdated laws has been to discourage discussion of LGBT issues throughout the school environment, from curricular instruction to counseling to library resources to GSA programming. Many teachers avoided or silenced any discussion of LGBT issues in schools. At times, this was because they were unsure what it meant to “advocate” or “promote” homosexuality and feared they would face repercussions from parents or administrators if they were too frank or supportive of students. At other times, teachers refused to teach the antiquated, discriminatory messages that some no promo homo laws require them to convey when homosexuality is discussed, and so declined to address LGBT topics at all. Without clear instruction on what the laws permit, many teachers reported that they or their colleagues erred on the side of caution, excluding information that parents or administrators might construe as falling within their scope.

Impact on LGBT Students of Discrimination and Victimization

In 2013, the Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network (GLSEN) found that discrimination and victimization of youth based on their sexual orientation or gender identity correlated with lower levels of self-esteem, higher levels of depression, and increased absenteeism from school.[22]

GLSEN’s findings are consistent with governmental and academic studies that consistently show that LGBT youth are at elevated risk of adverse mental health outcomes, including depression, anxiety, substance abuse, and suicidality.[23] According to a study by the Williams Institute, a research institute at the UCLA School of Law, a disproportionate 40 percent of youth experiencing homelessness identify as LGBT, due in large part to families rejecting their sexual orientation or gender identity.[24]

In 2016, the federal government’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey asked for the first time nationally about student sexuality, and found the 8 percent of students who identified as lesbian, gay, or bisexual nationally experienced higher rates of depression and suicidality than their heterosexual peers.[25] Data showed that an alarming 42.8 percent of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth respondents had seriously considered suicide in the previous year, and 29.4 percent had attempted suicide, compared with 14.8 percent of heterosexual youth who had seriously considered suicide in the previous year and 6.4 percent of heterosexual youth who had attempted suicide.[26]

A lack of support contributed to the prevalence of negative mental health outcomes; in one study, lesbian, gay, and bisexual students in environments with fewer supports like gay-straight alliances, inclusive anti-bullying policies, and inclusive non-discrimination policies were 20 percent more likely to attempt suicide than those in more supportive environments.[27] Studies have suggested that “[a] higher risk for suicide ideation and attempts among LGB groups seems to start at least as early as high school.”[28]

For LGBT youth, isolation and exclusion can be as detrimental as bullying and can aggregate over time to create an unmistakably hostile environment. In recent years, psychologists have drawn attention to these types of incidents—or “microaggressions”—and the way they collectively function to adversely affect development and health.[29]

“Incidents build up and eventually you blow up. I think microaggressions are seen as not important or damaging as violence, but they are, just in different ways,” Kayla E., a 17-year-old lesbian girl in Pennsylvania, said.[30] As Polly R., the parent of a gender non-conforming son in Utah, described the effects of a hostile environment in schools: “It’s like walking through a hailstorm. It’s not like any one piece of hail that gets you, it’s all the hail together.”[31]

Amanda Keller, director of LGBTQ Programs and the Magic City Acceptance Center at Birmingham AIDS Outreach in Alabama, said students often told her they wished fellow students would “just hit them or lash out rather than just ignoring them, ignoring their identity, walking into them and pretending there’s nobody there.”[32] Vanessa M., a counselor in Pennsylvania, said: “That stuff, it not only builds, but it takes a toll on their psyche where they don’t like themselves.”[33]

The discrimination and victimization that LGBT youth face in schools is often exacerbated when they have intersectional identities based on race, ethnicity, sex, disability, and other characteristics. LGBT youth of color, for example, often report bullying based on race and ethnicity, closer surveillance by school personnel, and harsher disciplinary measures.[34]

When students experience stigmatization, hostility, and rejection over years of schooling, the cumulative effect can be devastating and long-lasting. Psychological research has suggested that “circumstances in the environment, especially related to stigma and prejudice, may bring about stressors that LGBT people experience their entire lives.”[35]

II. Bullying and Harassment

Pervasive bullying and harassment of LGBT youth has long been a problem in US schools. In 2001, Human Rights Watch researchers documented widespread physical abuse and sexual harassment of LGBT youth, and noted that “[n]early every one of the 140 youth we interviewed described incidents of verbal or other nonphysical harassment in school because of their own or other students’ perceived sexual orientation.”[36]

Fifteen years later, bullying, harassment, and exclusion remain serious problems for LGBT youth across the US, even as their peers generally become more supportive as a group. The Human Rights Campaign has found that although 75 percent of LGBT youth say most of their peers do not have a problem with their LGBT identity, LGBT youth are still more than twice as likely as non-LGBT youth to be physically attacked at school, twice as likely to be verbally harassed at school, and twice as likely to be excluded by their peers.[37]

In 2016, the Youth Risk Behavior Survey found that 34.2 percent of lesbian, gay, and bisexual respondents in the US had been bullied on school property, and that lesbian, gay, and bisexual respondents were twice as likely as heterosexual youth to be threatened or injured with a weapon on school property.[38]

The impacts of bullying on youth can be severe, and legislatures across the US have recognized that bullying is a serious and widespread problem that merits intervention. In 1999, Georgia passed the first school bullying law in the US.[39] The rest of the US states followed suit, with the final state—Montana—passing its school bullying law in 2015.[40]

Although provisions of these laws vary by state, they typically define prohibited conduct; enumerate characteristics that are frequently targeted for bullying; direct local schools to develop policies for reporting, documenting, investigating, and responding to bullying; and provide for staff training, data collection and monitoring, and periodic review.[41]

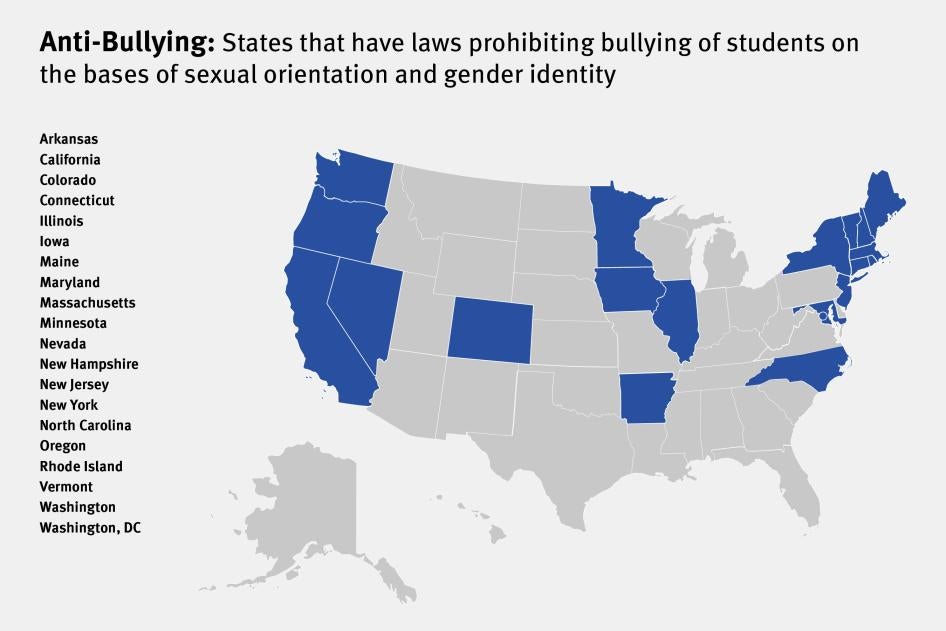

At time of writing, 19 states and the District of Columbia had enacted laws prohibiting bullying on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity statewide.[42] Research indicates that laws and policies that enumerate sexual orientation and gender identity as protected grounds are more effective than those that merely provide a general admonition against bullying.[43] Without express protections for sexual orientation and gender identity that are clearly conveyed to students and staff, bullying and harassment against LGBT students frequently goes unchecked.

Still, 31 states—including the five studied for this report— lack any specific, enumerated laws protecting against bullying on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity. In Alabama, Pennsylvania, Texas, and Utah, some school districts and schools had taken the initiative to enact inclusive, enumerated bullying policies; in South Dakota, however, state law expressly prohibits school districts and schools from enumerating protected classes of students.[44]

Schools that have enacted protections do not always clearly convey them to students, faculty, and staff. In interviews, many students and teachers expressed uncertainty or offered contradictory information as to whether their school prohibited bullying on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity, even in schools where enumerated protections were already in place.

Many students reported that school personnel did not raise the issue of bullying on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity at assemblies and educational programming on bullying held at their school.

For policies to be effective, students, faculty, and staff also need to know how targets of bullying can report incidents, how those incidents will be handled, and the consequences for bullying. Few of the 41 school policies reviewed by Human Rights Watch for this report contain clear guidelines detailing the protocol for reporting and dealing with bullying, making it unclear to students whether or how any reported incidents might be dealt with in practice.

Interviewees identified multiple types of bullying and harassment that they encountered in schools, each of which has consequences for LGBT students’ safety, sense of belonging, and ability to learn.

Physical Bullying

Most students interviewed indicated that physical violence was rare in their school. Students attributed this in part to a decrease in anti-LGBT attitudes among peers, both as a generational shift and among their cohort as they aged through high school. Some students also attributed this partly to zero tolerance policies and the perception that, though other forms of harassment may go unpunished, physical assault could result in serious consequences for perpetrators.[45]

Yet some students did face persistent physical violence at school and many said their schools took no effective steps to stop it. Sandra C., the mother of a 16-year-old gay boy in Utah, described a pattern of harassment that culminated in her withdrawing her son from the school:

My son was dragged down the lockers, called ‘gay’ and ‘fag’ and ‘queer,’ shoved into a locker, and picked up by his neck. And that was going on since sixth grade. They tried shoving him into a girl’s bathroom and said that he’s worthless and should be a girl.[46]

Some students who experienced physical violence hesitated to tell adults for fear that reporting would be ineffectual or make the situation worse. Willow K., a 14-year-old transgender girl in Texas, recalled being abused by members of the football team in seventh grade:

I came out that year, as gay, before I knew I was transgender, and I went into the locker room and everybody beat me up. I didn’t feel safe telling people because I thought they’d beat me up more.[47]

She added: “When I did tell somebody a kid was threatening to fight me, they did jack shit to stop it.”[48]

In one incident in Montgomery, Alabama in 2014, a gay high school student was surrounded and assaulted by a group of male students who punched and kicked him repeatedly, breaking his arm and leg. As Paul Hard, a counselor in Alabama, recalled:

The counselor and others came in to address the matter with the principal, and his response was to the effect of, ‘If you’d butch it up, this kind of thing wouldn’t happen to you.’[49]

Kevin I., a 17-year-old transgender boy in Utah, said:

I’ve been shoved into lockers, and sometimes people will just push up on me to check if I have boobs…. And I have reported… that I’ve been physically hurt because I’m trans, and I remember one of the administrators said, ‘It’s just because you’re so open about it.’ I’ve reported slurs and they say they’re going to go talk to them, but they never do.[50]

When administrators react indifferently to bullying and harassment, it can deter students from coming forward. Alexander S., a 16-year-old transgender boy in Texas, said:

I’ve been bullied my whole life, since kindergarten. I didn’t want to play dolls, and play with the girls in the classroom. I was more comfortable with the guys…. When I was eight, I started getting beaten up. When I realized what was going on, I told my teacher about the verbal bullying, she didn’t believe me, she called me a liar, because one of the bullies was her son. And I figured bullying wasn’t a big deal. I was already starting to be depressed at six or seven and started having suicidal thoughts. By nine, I realized the school wasn’t going to do anything…. I just kept it all bottled in.[51]

Alexander’s parents finally learned of the bullying after he attempted suicide. He has continued to struggle with depression and suicidal thoughts, and has been repeatedly admitted to inpatient care for treatment.

Verbal Harassment and Hostile Environments

Almost all of the students interviewed for the report reported encountering verbal harassment in their school environment, even in the most LGBT-friendly schools. In some schools, derogatory phrases like “that's so gay” and slurs like “dyke” or “faggot” were used by students to belittle or taunt peers, whether or not the targets identified as LGBT. Students stressed that even these generalized slurs contributed to a sense of hostility and danger in the school environment.

In each of the five states where interviews were conducted, researchers encountered schools where slurs were ubiquitous. Katrina I., a 17-year-old gay girl in Alabama, noted: “All the time, I hear slurs. I hear ‘queer’ thrown around a lot, the F word [faggot] thrown around a lot.”[52] Joel W., a genderfluid 17-year-old in Pennsylvania, said: “I hear slurs almost every single class.”[53] Ryan K., an 18-year-old student in South Dakota, concurred: “I hear it like every class period.”[54] In addition to “that’s so gay,” “faggot,” and “dyke,” transgender students reported encountering anti-transgender slurs like “tranny” or being referred to with dismissive, dehumanizing terms like “it” or “fe-man.”

Students also encountered anti-LGBT graffiti and slurs written on the school building, tests and papers, and personal property, and noted that their schools failed to investigate or rectify the vandalism. Kayla E., a 17-year-old lesbian student in Pennsylvania, said:

I’ve had to scrape ‘tranny’ and ‘faggot’ off the bathroom stall walls. I went to our center and told the secretary and she was like, ‘Oh, okay,’ but that was it.[55]

Molly A., a 17-year-old LGBT-identified student in South Dakota, described pervasive anti-LGBT graffiti: “All the bathroom doors in middle school have the F and G [gay] and Q [queer] words written all over them.”[56]

Lee W., a 15-year-old bisexual genderqueer student in Pennsylvania, said: “I’ve been called slurs in the hallway and I know teachers hear but they don’t say anything. I’ve been called a dyke and faggot.”[57] Ursula P., a 16-year-old transgender girl in Alabama, said:

Every other day people will yell and say negative things to me, like ‘You’re a guy,’ and it just really upsets me. I tell the teachers or counselors and they talk to the kid, but the same thing happens and it doesn’t help at all.[58]

Experiencing targeted verbal harassment had negative effects on student mental health. In addition to isolation, anxiety, and depression, harassment can exacerbate gender dysphoria, a condition where there is “a marked difference between the individual’s expressed/experienced gender and the gender others would assign him or her” that “causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.”[59]

Zack T., a 16-year-old transgender boy in Texas, said that “I mostly got verbal abuse, which was pretty degrading, and my dysphoria would go through the roof.”[60] Some students developed defenses to wall themselves off from abuse. Jayden N. a 16-year-old gay boy in Texas, said:

I’ve had someone yell ‘faggot’ at me, ‘queer boy,’ you hear people say ‘that’s so gay’ all the time…. In the beginning it was hard, but you get kind of used to it after a while.[61]

Students noted that some of the verbal harassment they encountered occurred in spaces that were unmonitored by teachers, administrators, and other staff, such as hallways, cafeterias, buses, and locker rooms. Yet even in classrooms and in communal spaces where school personnel were present, many students said teachers did little to intervene to stop slurs and verbal harassment.

Colin N., an 18-year-old transgender boy in Pennsylvania who heard slurs daily, said:

I think it’s a mix of, it’s not in the teacher’s earshot, or teachers don’t want to deal with it, or it’s around teachers who feel the same way. I’ve never been around where a kid has gotten called out for saying something like that.[62]

Charlie O., a genderfluid 17-year-old in Texas, described a similar incident:

In sophomore history class, we had to stand up and say our name and one thing we’re part of, and I said ‘Charlie, and GSA,’ and a girl said ‘what’s GSA?,’ and a boy in the corner said, ‘That’s the faggot club.’ The teacher just kind of looked at him. The teachers turn a blind eye.[63]

Noah P., a 14-year-old transgender boy in Texas, said: “A guy asked my teacher, ‘Right, gay people are going to hell, right?’ And she didn’t say a thing. They don’t do shit.”[64]

Students said that when teachers did intervene, intervention was at times sporadic or inadequate. Daisy J., an 18-year-old student in Alabama, said, “A kid will say [a slur] like seven times, and if she talks to them, it’s after everyone leaves.”[65]

Arthur C., a 34-year-old transgender teacher in Texas, recalled hearing slurs 10-20 times a day at the middle school where he taught. “If I sent them to the female AP’s (assistant principal’s) office, they’d be back in my classroom within five minutes. ‘Don’t write them up for this, it’s not worth my time.’”[66] At the high school where he taught later, Arthur said, “I’d hear stuff in other teachers’ classrooms … but they just wouldn’t even acknowledge it.”[67]

Other teachers also acknowledged that slurs were prevalent and used within earshot of school personnel. Monica D., a 37-year-old teacher in Utah, said: “I absolutely hear slurs. Frequently, kids still say, ‘That’s so gay,’ or I hear them say, ‘You’re a fag,’ or whatever.”[68] Lillian D., a teacher and GSA advisor in Pennsylvania, suggested that non-intervention was a deliberate, if flawed, strategy for educators:

A lot of teachers ignore it hoping it’ll go away, but when they don’t speak up, students assume it’s okay with that teacher.... But this is an area where that strategy doesn’t work.[69]

Interviewees indicated that teachers lacked training or support to know when and how to intervene when slurs were used. As Isabel M., a GSA advisor in South Dakota, said, “They’re just letting these things go over their heads. They don’t know how to deal with it, and they don’t recognize it.”[70]

In some instances, teachers and administrators’ willingness to effectively respond to slurs was compromised by laws or policies restricting the discussion of LGBT issues in schools. Alice L., a 53-year-old mother of a transgender student in Utah, said: “I’ve talked to teachers who are like, ‘I’d like to stop it, but I don’t know what to say, and particularly in light of Utah’s laws where I can’t promote homosexuality.’”[71]

In some instances, teachers responded to slurs in ways that affirmatively encouraged verbal harassment. Eric N., a 22-year-old transgender man in Pennsylvania, recalled: “In chemistry, students called me ‘faggot,’ and the teacher just laughed along…. it just sets the tone for the whole rest of the day.”[72] Rebecca P., a 19-year-old pansexual woman in Utah, said:

They saw it as a joke, like, ha ha ha, you’re so gay, and the teachers would laugh along with it instead of stepping in. A few teachers here and there might have stepped in, but most were weirdly okay with it.[73]

Lynette G., the mother of a young girl with a gay father in South Dakota, said the role of teachers in teasing was problematic as early as elementary school:

My daughter was eight, and she ran home because they were teasing her. Like, ‘Oh, your dad is a cocksucker, a faggot, he sucks dick.’ Just mean, nasty stuff…. [T]he teachers laughed, along with the kids teasing. She saw a teacher laughing and that traumatized her even worse.[74]

In addition to tacit encouragement, some teachers themselves made dismissive or derogatory comments about LGBT people, sometimes passing off such remarks as jokes and on other occasions appearing to intend disparagement. Bianca L., a 16-year-old bisexual girl in Alabama, said:

My biology teacher my freshman year would bring in kids who were wearing short shorts or weird sweaters and say, ‘You’d better take that off, you’re going to look gay.’ But she’d say it in front of the whole class.[75]

Michelle A., a genderfluid 18-year-old student in South Dakota, said: “I built something in a day … and I said it wasn’t really good, and he [the teacher] said, ‘Well, that’s lesbian construction.’”[76]

Tristan O., a 21-year-old transgender man in Pennsylvania, recalled that when he was in school, many of his teachers made gay jokes with students, and “when teachers or authority figures make comments, you’re stuck with those people in school. And that chips away at you.”[77] Kelly A., a 19-year-old gay cisgender woman in Utah, remembered: “Teachers said ‘that’s so gay’ – my gym teacher, a math teacher, and a science teacher.”[78] Students also identified coaches and JROTC [Junior Reserve Officers Training Corps] personnel who called students “gay,” “fags,” or feminizing or sexist terms. Eliza H., an 18-year-old bisexual girl in Alabama, recalled: “[M]y girlfriend walked me to class and she came in and held my hand, and [the teacher] told me we’re going to hell because we’re together.”[79] Cheyenne F., a 17-year-old transgender student in Alabama, recalled being told in class by a health teacher “that America’s acceptance of gays and abortion was the cause of the fall of the Twin Towers,” a reference to the attacks of September 11, 2001.[80]

Condemnation of students on religious grounds was particularly evident in interviews in Utah. Approximately 60 percent of Utah’s population belongs to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, more commonly known as the Mormon Church. Across the state, public schools give students release time in which the school disclaims responsibility for the student and allows them to leave the campus. During this period, students may attend seminary classes in church buildings adjacent to public schools for religious instruction. Students described strong pressure to attend seminary.

The de facto arrangement between public schools and the church can expose students to overtly anti-LGBT messages. Acanthus R., a 17-year-old non-binary transgender student in Utah, described seminary classes at their school as “a boiling pot of hate.”[81] Frankie S., a 17-year-old pansexual student in Utah, said: “They’ll tell you God made male and female and we don’t violate that.”[82]

When students presented a different point of view, they said they were rebuked. Brenda C., a 17-year-old pansexual student in Utah, described a friend being “called a heathen by a seminary teacher.”[83] Lacey T., a 15-year-old bisexual student in Utah, said her brother was kicked out of seminary for disagreeing with students expressing anti-LGBT positions.[84]

In interviews, teachers themselves recalled colleagues making derogatory comments to students. Arthur C., a 34-year-old teacher in Texas, said: “If a teacher ever told a kid they were damned for the color of their skin, they’d be fired instantly. But there’s no consequence when they say it to LGBT kids.”[85]

Cyber Bullying

LGBT students described a double-edged relationship with technology and social media, which allowed them to find communities online to explore their sexual orientation and gender identity, but also exposed them to bullying and harassment.

Students acknowledged that cyberbullying is a problem for middle and high schoolers generally, but said LGBT students could be particularly vulnerable to harassment. Miley D., a 17-year-old bisexual girl in Alabama, suggested: “Online, if you’re open about anything about yourself, you’re prone to be bullied. And if you’re LGBT, it’s 10 times worse.”[86]

In some instances, students took advantage of anonymous apps to target and harass LGBT peers. Eliza H., an 18-year-old bisexual woman in Alabama, recalled: “I was cyberbullied by a few of the guys on the football team because they found out I liked girls ... they kept making fake accounts and saying things over and over.”[87]

In other instances, students circulated unflattering photos or videos to misgender, mock, and embarrass LGBT peers online. Willow K., a 14-year-old transgender girl in Texas, described how other students constructed a website using “my real name … called ‘Kyle Sucks’ with a bunch of pictures about me, calling me an ugly fatass. And there’s a guy who always takes Snapchats of me and calls me a ‘he/she’ and shares them.”[88]

The public exposure and ridicule that students face as a result of cyberbullying can have negative repercussions for their mental health and academic achievement. Carson E., a 28-year-old teacher in Utah, described an incident where students filmed one of his gay students rehearsing a role for the school musical and put it on Facebook, where it rapidly spread with mocking comments. “He stopped going to school for a while,” Carson said. “And his grades are just awful, and last year they were straight As.”[89]

Yet when cyberbullying occurred, many students indicated that their schools were reluctant or ill-equipped to respond. Natalie D., a 17-year-old agender student in Utah, noted: “We’re told with cyberbullying that there is no proof so there’s nothing they can do about it.”[90] Students reported that they had brought threats of physical violence, including death threats, to the attention of their schools, and nothing was done.

Alexander S., a 16-year-old transgender boy in Texas, said:

I started getting a lot of anonymous people telling me to kill myself, that it wasn’t worth living. I called the school and told them what was going on and they didn’t do anything. The crisis counselor … said we couldn’t do anything because we didn’t know who the kids were.[91]

Sexual Harassment

Unlike gay and bisexual boys, who were rarely treated as sex objects by their peers, lesbian and bisexual girls said they were regularly propositioned for sex by straight male classmates.

Bianca L., a 16-year-old girl in Alabama, explained: “I’m bisexual, and every time I come out to a guy, it’s always, ‘Can I see you make out with a girl, or want a threesome?’”[92] Catherine G., a 17-year-old asexual girl in Alabama, said: “I started identifying as asexual last year, and all of a sudden everybody wants to be in my pants. I’m a challenge now.”[93]

Other students described invasive questions about sexual practices and genitalia, which were most often reported by transgender and gender non-conforming youth. Kayla E., a 17-year-old lesbian girl in Pennsylvania, said:

People will ask really intrusive questions about your sex life when they find out you’re a non-straight woman. They ask questions you wouldn’t ask anyone else. I feel like queer women are oversexualized and that’s mistaken as acceptance.[94]

Dominic J., a 13-year-old transgender boy in Pennsylvania said: “I get a lot of questions, like really inappropriate questions, like about my down there and my up here.”[95]

In addition to sexual harassment, lesbian and bisexual girls and transgender and gender non-conforming students were subject to overt threats of sexual assault. Tracy M., an 18-year-old in Texas, said:

I’ve experienced a lot of verbal sexual harassment. I didn’t really accept the label lesbian, and I had one guy tell me he was going to rape me and change me.[96]

Julian L., a 15-year-old transgender boy in South Dakota, described being threatened during his freshman year by a senior:

At one point he was like ‘What do you have between your legs,’ and I said, ‘Why do you need to know that,’ and he was like, ‘I need to know if I can rape you.’[97]

Some lesbian and bisexual girls and transgender and gender non-conforming students were physically groped and touched by young men who learned they were LGBT. As early as middle school, lesbian and bisexual girls and transgender and gender non-conforming students described being targets for unwanted touching and sexual assault. Alexis J., a genderfluid 19-year-old in Texas, recalled “straight up sexual assault” by “people who would just grab my butt or my boobs or my crotch,” to see if they were “real.”[98]

Students said some teachers failed to take sexual harassment seriously.[99] Daniel N., a 17-year-old student in Texas, said: “You know teachers hear sexual harassment, and they take it as, oh, they’re just joking around, and kids will be kids.”[100] Lacey T., a 15-year-old bisexual girl in Utah, recalled that when she was a freshman:

One guy would always ask my pansexual friend and I if we wanted to have a threesome. It got to the point where I had to tell the teacher about it, and she said, ‘Oh, he’s just messing around.[101]

Exclusion and Isolation

Even in the absence of overt bullying and harassment, LGBT students in each state where interviews were conducted suggested they felt alone or unwelcome in their school environment. Schools are difficult environments for many youth, but for LGBT youth, isolation and exclusion are exacerbated by a lack of role models, resources, and support that other students enjoy. Lucia Hermo of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Alabama noted the prevalence of these complaints even in districts where physical bullying was uncommon: “What we’re hearing is isolation, I can’t find anyone… and feel there’s something wrong with me.”[102]

A lack of friends and feelings of loneliness were common for LGBT youth. Jonah O., a 16-year-old gay boy in Alabama, said:

There aren’t… many out kids, so that kind of gives a sense of loneliness. There was a rumor that spread that I had a huge crush on this guy in my grade, and all my relationships with other guys in the grade kind of halted at that point.[103]

Isolation can begin as early as elementary school; Raven C., a 10-year-old gay student in Texas, said he was shunned by peers after he came out: “People are friends with each other, but they treat me like I’m a shadow.”[104]

Isolation and exclusion were particularly difficult for many LGBT students because it was not something they felt they could report. Students isolated and excluded LGBT peers in ways that were apparent to those students but not so obviously egregious that teachers or administrators would take any one incident seriously. Tristan O., a 21-year-old transgender man in Pennsylvania, said: “It’s nothing you can hit with a hammer. You know what they’re doing, and it hurts you, but they know it’s just small enough that it’ll slide.”[105]

A common example was belittling comments or exclusion from group activities. As Ginger M., a 17-year-old bisexual girl in Utah, asked: “[H]ow do you go to the administration with that? Someone laughed because I’m gay?”[106] According to Dave W., a 44-year-old teacher and GSA advisor in Pennsylvania, such slights “make a difference after a while… People don’t look you in the eye, teachers don’t call on you in class, they have lower expectations of you.”[107]

School policies and programs can contribute to the isolation and exclusion of LGBT youth, including holding school dances where same-sex dates are discouraged, and school spirit days like “gender switch day.” Ursula P., a 16-year-old transgender girl in Alabama, described how the school yearbook photographer “told me that if I appeared in the yearbook, they’d use my legal name. I asked him to use my real name and he said he wouldn’t, so I told him not to include me in it.”[108] When teachers and administrators signal to students that they are not full members of the school environment, it can exacerbate the isolation and exclusion they already face from peers.

LGBT students responded to isolation and exclusion in different ways. Some recounted how they carefully policed their behavior, dress, and friendships to fit in and avoid harassment. Max R., a 13-year-old student in Pennsylvania, commented:

You almost have to be really cautious with what you do. You can’t be yourself. Even from allegedly straight students, any sort of weird thing they’ll do with each other, it’s like, ‘Whoa, that’s gay, man.’[109]

Others responded by distancing themselves even further from their peers. Caleb C., a gay non-binary 20-year-old in Utah, recalled:

A lot of what I did to be safe was to be even more outrageous. If I’m so queer that nobody will talk to me, they won’t hurt me. I did things to make myself much more gay: play up my gay lisp, feminize my voice, feminize my speech, I had hella long pink hair. That was my thinking, become such an outsider they won’t even approach me.[110]

Exclusion and Isolation by LGBT Peers

Even spaces created for LGBT youth at times failed to serve all youth equally. Some interviewees noted that the GSAs at their schools were inclusive only of students who identified as gay or straight, and had little to offer to students with other identities. Cassidy R., a pansexual agender 18-year-old in Utah, did not pay attention to their school’s GSA “because I felt like I wasn’t included in the conversation, and it really didn’t pertain to me.”[111]

Other LGBT students described outright discrimination or hostility from LGBT peers. Christopher I., a gay transgender 18-year-old in Texas, explained: “The worst I got was from gay guys. Whenever I’d meet guys who were really proud to be gay, they’d be like, ‘Oh, I hate vaginas.’ And being a gay trans guy, I’m like, okay, bye.”[112] Anthony G., a 16-year-old demisexual transgender boy in Texas, said:

The LGBT community is sometimes mean to each other. I met someone who’s pansexual, and we were just talking and getting to know each other, and that came up, and I said, ‘Cool, I’m trans,’ and they were like, ‘Yeah, do you have guy parts,” and they were like, ‘Then you’re a female.’[113]

Furthermore, LGBT students of color experienced intersectional isolation as a product of their sexual and gender identities and racial, ethnic, and national identities. Nora F., a school administrator in Utah, said: “If a student is LGB or T and a child of color, these issues are different. They’re more likely to be harassed, they’re less likely to be intervened with, they’re more likely to face disciplinary proceedings in schools.”[114] Students also noted that being LGBT and a person of color could prove isolating in environments where their LGBT peers were predominantly white and their peers who were students of color were predominantly heterosexual and cisgender.

Reporting and Retaliation

Schools typically encourage students to report when they are bullied or harassed by students or adults. Yet some students who did report physical bullying, verbal harassment, or sexual harassment were rebuffed.

Garrett B., a 16-year-old pansexual transgender boy in Alabama, described inaction when he reported threats of physical violence:

I got a death threat and they did nothing about it. There’s a guy who really hates me for being trans and he was like, ‘I’m going to shoot you in the face,’ and the administration said there was ‘conflicting evidence,’ which probably just means he said he didn’t do it.[115]

Silas G., a 15-year-old transgender boy in South Dakota, said: “Bullying got to the point where someone told me to kill myself, and I told a teacher, and they didn’t do anything.”[116]

Students reported being told their schools could not address bullying or harassment without proof, and used the fact that they lacked the evidence necessary to discipline a student to justify inaction. Furthermore, students who tried to document various forms of bullying and harassment with their phones or cameras found themselves being punished for using devices in school.

Noah P., a 14-year-old transgender boy in Texas, said:

I got in-school suspension for recording bullying on my phone… because you can’t film another person without their consent.[117]

Students who engaged or fought back faced additional barriers or punishment, even when the instigator went unpunished. Ginger M., a 17-year-old bisexual girl in Utah, said:

I was sexually harassed for like five months.… And these text messages just kept going. And I started swearing at him. I screenshotted the messages, they were on Facebook Messenger, and I went to the school and the cops, and they said, ‘Well, you fought back.’[118]

Jordan L., a gay 17-year-old student in Texas, said:

There’s one kid who goes to my school who wore an earring. And they’d be picking and picking, and he’d argue back, and he’d get in trouble but the other students wouldn’t get in trouble. One time a girl hit him and he hit back, and he got in trouble but she didn’t.[119]

III. Exclusion from School Curricula and Resources

Schools directly teach and instruct students with curricular offerings. But they also provide physical and mental health resources, library materials, access to the internet, extracurricular and noncurricular activities, and opportunities to socialize. In each of these areas, students noted that LGBT perspectives were either neglected or expressly excluded on the grounds that they were not appropriate or relevant for youth.

As LGBT people become more visible, research suggests that students are coming out or exploring their sexual orientation and gender identity at younger ages. The silence surrounding LGBT issues in schools not only sends a message to students that their identities are somehow inappropriate, but leaves them ill-prepared to deal with issues that schools equip their heterosexual and cisgender peers to handle.

Classroom Instruction and Discussion

In each of the five states examined in the research for this report, most students said that their teachers had never raised or discussed LGBT issues in class. Logan J., an 18-year-old pansexual non-binary student in Utah, said: “I haven’t really had teachers mention LGBT issues at all. Nobody likes to mention it. And any time someone brings up the issue, it’s just skimmed over.”[120] This was not only true of health classes, but of English, government, history, social studies, sociology, psychology, and other courses where LGBT themes and issues might naturally arise in the curriculum.

Adults echoed students’ perceptions that teachers and administrators treated LGBT issues more cautiously than others. Amy L., a teacher in Pennsylvania, said: “We read Will Grayson, Will Grayson last year, and a lot of the male students didn’t want to read it because it had two students that are gay, and the school let them opt out and read a different book. We don’t do that for other things.”[121]

When LGBT issues did come up in class, students said it was often as a debate in a government or current affairs class, where the teacher remained pointedly neutral on the topic. Some students took offense at this type of approach to LGBT issues, noting that it placed their identities, relationships, and morality up for debate and exposed them to scrutiny in ways their peers did not experience. Fatima W., an 18-year-old girl in Alabama, said:

[T]hey’ll say, I think it’s a discussion, so everyone can voice their opinion, and someone always says ‘I don’t agree,’ and I get so mad. They don’t let us debate whether black and white people can marry.[122]

Teachers in some schools silenced students who attempted to raise LGBT issues as a topic of discussion. Rowan C., a 15-year-old pansexual genderfluid student in Alabama, noted:

We learn about the civil rights movement, the women’s rights movement, but not LGBT movements. We even tried to bring it up in class and got shot down… and it was the teacher shutting it down.[123]

In some instances, teachers rebuked students for speaking up about LGBT issues. Angela T., a 17-year-old girl in Pennsylvania, said:

I remember in middle school, asking about same-sex relationships, and being totally shut down, and being pulled aside by an administrator and told that’s not something we talk about.[124]

In some instances, teachers rebuked students who brought up LGBT issues or themes. Catherine G., a 17-year-old asexual girl in Alabama, recalled one such incident in a story-writing exercise in seventh grade:

A girl wrote this great story about a man whose wife leaves him because he was gay, and she actually got [reprimanded] and her parents were called because they said it was inappropriate and not acceptable in a school environment.[125]

Even some supportive teachers, fearing backlash, expressed reluctance to engage with LGBT topics in class. Sharon B., a teacher and GSA advisor in Alabama, said:

I’m conscious that students think of me as the GSA sponsor, and I think I hold back from teaching too much LGBT content—and even gender content—in my English class because I know some students are just waiting and ready to say I’m pushing an agenda.[126]

Horacio J., a teacher and GSA advisor in Alabama concurred:

Teachers, their default is just to not talk about it. They’re not trained to talk about subject matter like that.... we have to be careful about what we say in the classroom because all it takes is one student complaining to mom and dad and it becomes a huge problem—a school problem, and potentially a school district problem.[127]

Teachers’ reticence to talk about LGBT issues stems both from the existence of laws restricting their speech and a lack of training and guidance about what those laws do and do not prohibit. Joe J., a teacher and GSA advisor in Utah, said: “I know a lot of teachers teach less than they can legally because they’re either unsure what they can teach or worry they’ll get in trouble.”[128] Hannah L., a teacher in Utah, described how the no promo homo laws shaped her curriculum:

It’s scary, as a teacher, because I can be fired if a parent gets upset enough about something that happens in my class…. There are so many LGBT issues that are happening in the world, if I’m going to run an authentic English classroom, we need to be able to talk about it. And it’s asinine that as a competent teacher I’m not given the leeway to have the conversations we need to be having.[129]

Comprehensive Sexuality Education

In each of the states where interviews were conducted, students said the sexuality education they received was nonexistent or inadequate—only teaching abstinence, for example—often because it was not taught or was not a required component of the curriculum. However, when it was taught in their school, they said it was especially limited for LGBT youth.

Some teachers placed LGBT issues off-limits or made clear they would not be teaching about same-sex activity. Miley D., a 17-year-old bisexual girl in Alabama, described how the coach who taught her health class:

told us he was only teaching what’s in the book. But what’s in the book is that marriage is between a man and a woman…. Sex is between a man and a woman. He told us outright the first day of class that he would not teach about anything gay or lesbian.[130]

Evan H., a 19-year-old man in Utah, said:

Health was taught by the wrestling coach, who was a 70-year-old devout LDS [Latter Day Saints] man…. The only time they brought up gay anal sex was when he said… ‘The butt is not meant for sex.’[131]

When instructors did deal with LGBT issues, it was common for them to suggest that gay men would contract HIV. While sexuality education can and should explain that HIV and other STIs can be transmitted through same-sex activity, students recalled classes where LGBT people were only treated as vectors of disease, and with little or no discussion of the ways LGBT people might protect themselves with safer sex practices. “The only time they mentioned homosexuality in high school was to say that if you’re homosexual you’d get AIDS,” Damien N., a 24-year-old straight man in Alabama said.[132]

Placing the onus on students to ask questions or raise LGBT issues made it difficult for them to elicit the information that they needed to lead safe, healthy, and affirming sexual lives. For many students, it was not clear what information they would need in the future or what questions they should ask. Caleb C., a gay non-binary 20-year-old in Utah, said: “Utah teaches abstinence plus, so it’s abstinence only but students can ask questions. Which sucks, because kids don’t know what to ask.”[133]

Even when they had specific questions, some LGBT students did not feel comfortable asking for further information in front of their peers. “We were scared, we didn’t want to get taunted, so we weren’t going to ask in class with all the straight kids,” Malik F., a 19-year-old bisexual man in Pennsylvania, said.[134] When students did bring in LGBT perspectives, they were sometimes not taken seriously or disciplined for doing so. Lacey T., a 15-year-old bisexual girl in Utah, recalled a classroom discussion about safe sex.

[The teacher] said, ‘How do we avoid getting pregnant?’ and you can say anything. And I said, ‘Have sex with someone of the same sex,’ and I got kicked out of class.[135]

When students themselves tried to raise questions that were pertinent to LGBT youth, instructors more typically reacted with embarrassment or deflection. Kevin I., a 17-year-old transgender boy in Utah, said:

In my health class, LGBT issues came up because somebody mentioned it, but the teacher just kept going on about how female and male reproductive systems work. He just changed the subject.[136]

The existence of no promo homo laws has a particularly chilling effect on LGBT-relevant education. In Alabama, Texas, and Utah, teachers and administrators repeatedly underscored their uncertainty about what the law actually prohibited them from saying. “It creates this kind of haze; teachers and counselors don’t know how to address the issue,” said Troy Williams, executive director of Equality Utah.[137]

LGBT rights advocates note that the Texas law only pertains to the content of model curricula issued by the state, for example, but Kevin D., a teacher in Texas, explained to researchers, “[i]t is written into the code that health teachers are supposed to stress that homosexuality is against the law.”[138] Nora F., a Utah administrator, said most teachers “aren’t formally trained on what the no promo homo law means,” and “the … understanding is that you can’t say anything about LGBT identity, harassment, anything.”[139]

As a result, many teachers err on the side of avoiding any discussion of LGBT issues at all, in sexuality education and in the curriculum generally. Even in Pennsylvania and South Dakota, which did not have a statewide no promo homo law, individual schools imposed their own limits on discussions of same-sex activity. These took various forms, from regulating curricula to restricting what teachers say in the classroom to punishing teachers who addressed LGBT issues in a frank manner.

Pauline J., a community health educator in Pennsylvania, described

a school district where I teach where you’re not allowed to talk about homosexuality…. and the reasons why have been explained to me and they don’t make sense…. There’s a lot of topics I cover and the teacher is like, ‘You probably can’t discuss that, because you’d have to talk about sexual orientation, and you can’t do that.’[140]

As a result of these formal and informal restrictions, LGBT students were unable to access information that would be relevant to them as part of their sexuality education, including risks associated with same-sex activity or routes of transmission other than penile-vaginal intercourse. Brayden W., a 17-year-old gay boy in Utah, recalled trying to ask about safer sex and being rebuffed: “In my health class I tested the water by asking [the teacher] about safer sex because I’m gay. He said he was not allowed to talk about it.”[141] Gabriel B., a 19-year-old gay man in Utah, similarly recalled a lesbian classmate who

[r]aised her hand and asked, ‘What about me?’ And the teacher said, ‘I can’t really discuss that,’ and went over it really quickly, and then said that Utah state law prevents her from discussing it in class.[142]

In addition to LGBT issues, some students said that asexuality was not addressed in health curricula. Andrea L., a 17-year-old asexual girl in Pennsylvania, said:

When I was younger, I never felt sexual feelings toward anyone. I thought that was abnormal of me. And nobody taught me that was an okay feeling to have.[143]

The lack of information was exacerbated by the tendency for LGBT students to tune out the sexuality education they did receive because they felt it did not pertain to them. “If you’re gay, and you’re being taught all this stuff that’s irrelevant to you, you just don’t pay attention,”[144] said Gabriella B., a 17-year-old bisexual girl in Pennsylvania.

The need for LGBT students to receive comprehensive sexuality education is clear. LGBT youth encounter a number of health issues that existing health classes fail to address. As Pauline J., a community health educator in Pennsylvania, said:

LGBT inclusive sex ed saves lives. LGBT students are not being heard at all, in any class. And there’s research saying the unintended pregnancy rates among LGBT youth is higher than straight youth. And the reason is that sex ed goes right over their heads. When we say “the man and the woman,” and you’re gay or trans, you’re tuning that out.[145]

Although discussions of same-sex activity were restricted at the state level and by individual schools and instructors, transgender issues were also virtually absent from classroom discussions, despite the unique health concerns that transgender youth face. Joel W., a 17-year-old asexual, genderfluid student in Pennsylvania, said:

They don’t cover trans stuff, like binders. They should say, ‘Hey, don’t bind too long,’ or talk about the effects of different hormones.[146]

The absence of LGBT-inclusive information is particularly detrimental insofar as LGBT youth may not know where else they can obtain trustworthy information about sexuality. Many students either were not out to their parents or said their parents did not accept their sexual orientation or gender identity, limiting their ability to obtain information about sexuality when it was not provided at school.

LGBT students may also have a greater need for school-based comprehensive sexuality education insofar as their parents are unfamiliar with safer sex recommendations for LGBT people and cannot provide the information they need. According to Alison McKee, senior director of Education and Training at Planned Parenthood Keystone in Pennsylvania:

So many parents tell me, ‘Well, they’re getting sex ed at school, right?’ …. You can’t make that assumption. You can’t assume they’re covering the relevant topics, or that your student isn’t being left out.[147]

When schools did not provide information and students could not or did not get that information from their parents, they most often reported getting it from peers or the internet,[148] including Tumblr, a microblogging platform where users generate and post content. Students said such platforms were powerful tools, particularly for students exploring issues of sexuality and gender who were in rural areas or otherwise isolated from supportive resources.[149] But because content is user-generated, students who used the platform for sexuality education were effectively learning from peers, without any guarantee of the scientific and medical accuracy of the information they received.

Cameron S., a 16-year-old boy in South Dakota, said:

I get information from word of mouth, which is a horrible way to get it. What gets passed around is semi-accurate or not explained at all.[150]

In the absence of sexuality education that discussed the mechanics of same-sex activity, students also indicated they learned about sex by viewing pornography or engaging in sexual activity with more experienced partners. When asked how students learned about safer sex, Camille V., a biromantic 17-year-old girl in Alabama, remarked with a shrug: “Hope the other person knows what they’re doing.”[151]

Refusal to convey accurate, nonjudgmental information about same-sex activity and other LGBT issues puts LGBT youth at heightened risk of sexually transmitted infections, including HIV. Maureen Gray, coordinator of the Northeastern Pennsylvania Rainbow Alliance, recalled a conversation with a HIV-positive young man in his early twenties:

[H]e said to me, ‘I wish I had known more about HIV transmission…. [I]n high school, it’s just this really cursory mention, and I really didn’t know, and now I’ve got a life sentence, you know? Because I didn’t know.’[152]

The lack of information about safer sex for LGBT youth is compounded by stigmatization and isolation, which may increase the likelihood that students engage in risky behavior. As Kate Bennion, director of satellites for OUTReach Resource Centers in Utah, observed: “If you think, ‘Oh, well, if I’m gay and I’m going to hell, I might as well have sex,’ there’s a little bit of a fatalist mentality.”[153]

The absence of LGBT-inclusive comprehensive sexuality education not only left students ill-equipped to navigate sexual activity, but often exacerbated feelings of difference, exclusion, or stigmatization. Students underscored that the sexuality education they received took for granted that they were cisgender and heterosexual. Discussions of puberty and bodily development presumed that students were cisgender; indeed, some students were divided by sex, so students who were assigned female at birth attended a discussion of women’s development and bodies and students who were assigned male at birth attended a discussion of men’s development and bodies.

Similarly, students noted that discussions of sexual activity, relationships, and marriage almost always operated under the assumption of heterosexuality. When same-sex relationships were acknowledged, students said it was typically as a cursory aside rather than a consistent, integrated recognition of their equal validity.

Counseling and Support

Many schools provide counselors to ensure that the academic and mental health needs of students are reliably met. Counseling is particularly important for LGBT youth, who face stressors at home and in schools that put them at a high risk for adverse mental health and academic outcomes.

As a result of bullying, exclusion, and isolation, many LGBT youth are at increased risk of adverse mental health outcomes. Studies have shown that LGBT youth experience higher incidences of depression, anxiety, substance abuse, and suicidality than their heterosexual, cisgender peers.[154]

Discrimination in school environments also adversely affects the academic achievement of LGBT youth. A recent survey from GLSEN found that LGBT youth who faced discrimination in school had lower GPAs and were more than three times more likely to miss school in the past month than those who did not.[155] In the aggregate, LGBT youth who experienced high levels of victimization because of their sexual orientation or gender identity were twice as likely as those who experienced lower levels of victimization to say they did not plan to go on to post-secondary education.[156]

These findings suggest that LGBT youth are in particular need of counselors who are attuned to their unique needs and risk factors. Unfortunately, students often lack access to supportive, culturally competent counseling in schools. None of the states surveyed required counselors to be trained on sexual orientation or gender identity, leaving it up to individual counselors to seek out cultural competency training on LGBT issues.

Monica D., a teacher in Utah, said the counseling center at her school was “not a safe place” for LGBT youth.[157] She noted: “I recently went through the suicide prevention training … and there’s no mention of LGBT students at all.”[158]